Published online Feb 27, 2022. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v14.i2.120

Peer-review started: October 7, 2021

First decision: December 4, 2021

Revised: December 15, 2021

Accepted: February 10, 2022

Article in press: February 10, 2022

Published online: February 27, 2022

Processing time: 138 Days and 13.6 Hours

For total laparoscopic distal gastrectomies for gastric cancer, the reconstruction method is critical to the clinical outcome of the procedure. However, which reconstruction technique is optimal remains controversial. We originally reported the augmented rectangle technique (ART) as a reconstruction option for total laparoscopic Billroth I reconstructions. Still, little is known about its effect on long-term outcomes, specifically the incidence of postgastrectomy syndrome and its impact on quality of life.

To analyze postgastrectomy syndrome and quality of life after ART using the Postgastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Scale-37 (PGSAS-37) questionnaire.

At Juntendo University, a total of 94 patients who underwent ART for Billroth I reconstruction with total laparoscopic distal gastrectomies for gastric cancer between July 2016 and March 2020 completed the PGSAS-37 questionnaire. Multidimensional analysis was performed, comparing those 94 ART cases from our institution (ART group) to 909 distal gastrectomy cases with a Billroth I reconstruction from other Japanese institutions who also completed the PGSAS-37 as part of a larger national database (PGSAS group).

Patients in the ART group had significantly better total symptom scores in all the symptom subscales (i.e., esophageal reflux, abdominal pain, meal-related distress, indigestion, diarrhea, constipation, and dumping). The loss of body weight was marginally greater for those in the ART group than in the PGSAS group (-9.3% vs -7.9%, P = 0.054). The ART group scored significantly lower in their dissatisfaction of ongoing symptoms, during meals, and with daily life.

ART for Billroth I reconstruction provided beneficial long-term results for postgastrectomy syndrome and quality of life in patients undergoing total laparoscopic distal gastrectomies for gastric cancer.

Core Tip: Reducing the prevalence of postgastrectomy syndrome (PGS) and improving the quality of life (QOL) after gastrectomy for gastric cancer patients has become an important technical challenge for surgeons. We developed the augmented rectangle technique (ART) for Billroth I reconstruction after total laparoscopic distal gastrectomy. Our patient outcome results have been good in the short-term. Long-term patient outcomes have not been studied. Here, we evaluated PGS and QOL after gastrectomy with ART using the Postgastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Scale-37. Application of ART produced beneficial long-term PGS and QOL results in patients undergoing total laparoscopic distal gastrectomies.

- Citation: Yamauchi S, Orita H, Chen J, Egawa H, Yoshimoto Y, Kubota A, Matsui R, Yube Y, Kaji S, Oka S, Brock MV, Fukunaga T. Long-term outcomes of postgastrectomy syndrome after total laparoscopic distal gastrectomy using the augmented rectangle technique. World J Gastrointest Surg 2022; 14(2): 120-131

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v14/i2/120.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v14.i2.120

The postgastrectomy syndrome (PGS) is an almost inevitable functional disorder after a radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer[1-3]. In addition to precipitating weight loss because of a reduction in the size (or loss) of the stomach, PGS can also induce systemic disturbances, such as dumping syndrome. These problems can lead to deterioration of a patient’s long-term postoperative quality of life (QOL)[4,5]. Determining if there is a correlation between an increased risk of PGS and certain gastrectomy reconstruction techniques will ensure the optimal selection of appropriate surgical approaches to prevent and treat PGS. Importantly, it is appropriate to question how widely employed contemporary minimally invasive surgeries, such as laparoscopic gastrectomy, contribute to the risk of developing PGS.

Total laparoscopic distal gastrectomy (TLDG) for gastric cancer has evolved from a conventional laparoscopic-assisted gastrectomy to a more complex procedure incorporating more sophisticated techniques and instruments. Fukunaga et al[6] originally described the augmented rectangle technique (ART) as a novel Billroth I reconstruction after TLDG. ART for Billroth I reconstruction has been reported to have good short-term results, but no long-term PGS and QOL results have been reported.

The Postgastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Scale-37 (PGSAS-37) was developed by the Japanese Postgastrectomy Syndrome Working Party (JPGSWP) in 2015 to serve as an integrated questionnaire designed to assess postgastrectomy-specific clinical symptoms and QOL[7]. JPGSWP also initiated a multi-institutional nationwide surveillance program to investigate medium to long-term symptoms, living status, and QOL following various types of gastrectomies. The JPGSWP felt that it was necessary to create a standard tool to assess postoperative QOL after any surgical procedure performed at any facility in Japan. This also allowed the statistical analysis of national data collected for each gastrectomy performed at numerous institutions throughout Japan. A “PGSAS statistical kit” was also created to allow free access that allowed individual institutions to compare their own patient outcomes to those PGS outcomes from patients undergoing gastrectomy procedures anywhere else in Japan.

This study investigated the impact on PGS and QOL in patients at Juntendo University in Japan who underwent ART for Billroth I reconstruction compared to a national database of patients who underwent other reconstruction techniques from multiple institutions throughout Japan and who completed the PGSAS-37 form.

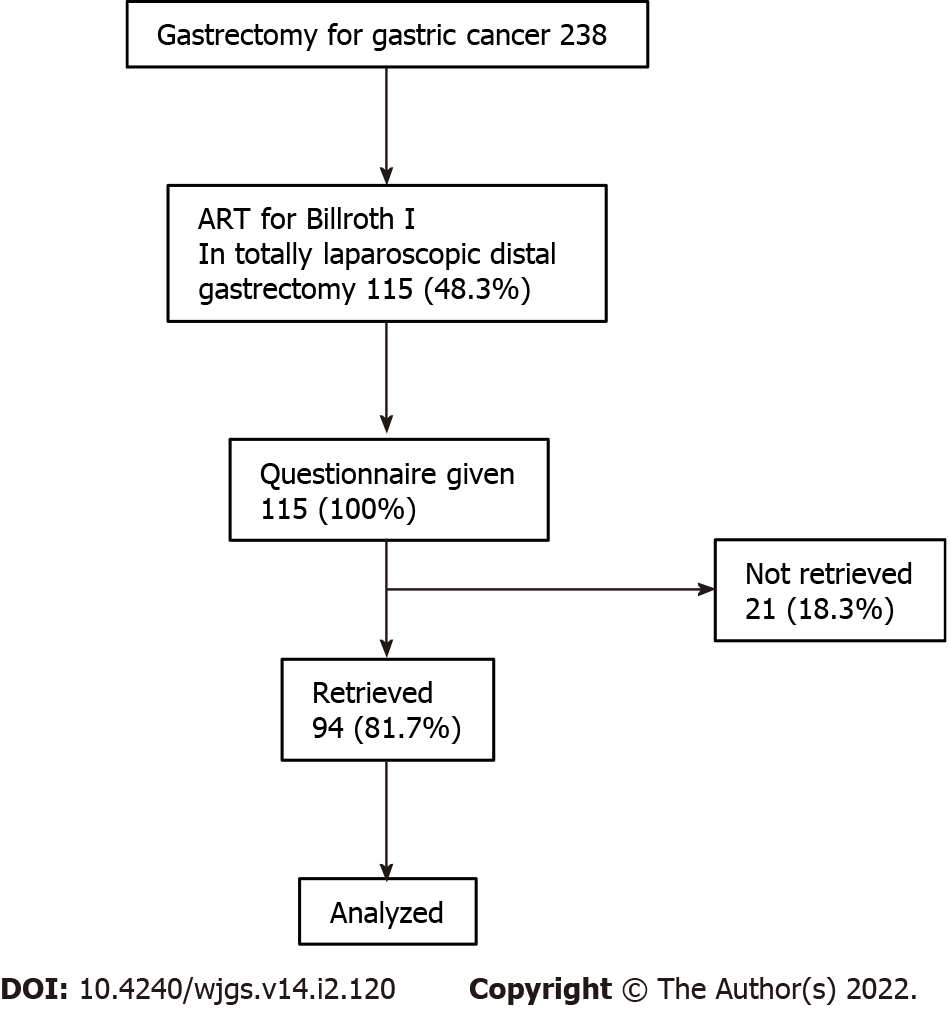

From 238 patients who underwent gastrectomy for gastric cancer at Juntendo University Hospital from July 2016 to March 2020, 115 (48.3%) had received a TLDG using ART for Billroth I reconstruction. A PGSAS-37 questionnaire was administered to all patients. Completed or nearly completed questionnaires were retrieved from 94 (81.7%) patients, and these patients were selected for inclusion in this retrospective study (Figure 1). Clinical, perioperative, pathological, and PGSAS-37 questionnaire data were collected and analyzed. Clinicopathological variables included postoperative observation period, age, sex, preoperative body mass index, pathological stage, approach, extent of lymph node dissection, and combined resection. Pathological stage was described according to the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma[8]. Perioperative outcomes included operative time, intraoperative blood loss, and conversion to open surgery. Postoperative complications, stratified using the Clavien-Dindo classification system[9], included postoperative hospital stay and adjuvant chemotherapy. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Juntendo University Hospital (Approval No. 20-192). The need for informed consent was waived in view of the retrospective and observational nature of the study. An opt-out approach was used by accessing a written disclosure on the study’s website (URL: https://www.gcprec.juntendo.ac.jp/kenkyu/files/6379827945f9a62a8f32ec.pdf).

ART is an anastomosis technique that uses three linear staplers (LS) for TLDG. After gastrectomy, an insertion hole is made in the duodenum and the remnant stomach stump on the greater curvature side. The thinner and thicker 60-mm jaws of the LS are inserted into the greater curvature ends of both the duodenal and remnant gastric stump. The lesser curvature end of the stapled duodenal stump is rotated externally 90°, and the device is closed and fired. After the initial suturing of the stomach and duodenum, the posterior wall and cranial wall form a V-shape. A 30-mm LS is used to close the insertion holes up to the closest side of the duodenal resection margin. This suture creates the third side, which is the caudal wall. Finally, the entire stapled duodenal resection is removed, using a 60-mm LS to create the fourth side that makes up the rectangular anterior wall. This series of operations creates an augmented rectangular gastroduodenal anastomotic stoma.

The PGSAS-37 is a multidimensional QOL questionnaire based on the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale[10,11]. The PGSAS-37 questionnaire consists of 37 questions with 15 items from the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale, and 22 clinically relevant items selected and added by the JPGSWP (Table 1). These additional items consist of eight assessing overall symptoms, two dumping syndrome, five meal quantity, three meal quality, one work status, and three life dissatisfaction. These items are aggregated into nine subscales, for a total of seventeen main assessable outcomes. Nine subscales are derived from the average score of the corresponding items and include an evaluation of esophageal reflux, abdominal pain, meal-related distress, indigestion, diarrhea, constipation, dumping, quality of ingestion, and dissatisfaction with daily life. The total symptoms score is calculated from the average of the seven symptoms subscale scores. The main outcome consists of three categories, namely symptoms, living status, and QOL (Table 2). In the PGSAS-37 questionnaire, high scores denote favorable outcomes regarding ingested amounts of food per meal, ingested amounts of food per day, appetite, hunger, satiety, the quality of food, and change in body weight. Low scores on most of the other items and for symptom subscales indicate favorable outcomes.

| Item | Subscales | ||

| Symptom | 1 | Abdominal pains | Esophageal reflux subscale (items 2, 3, 5, 16) |

| 2 | Heartburn | Abdominal pain subscale (items 1, 4, 20) | |

| 3 | Acid regurgitation | Meal-related distress subscale (items 17-19) | |

| 4 | Sucking sensations in the epigastrium | Indigestion subscale (items 6-9) | |

| 5 | Nausea and vomiting | Diarrhea subscale (items 11, 12, 14) | |

| 6 | Borborygmus | Constipation subscale (items 10, 13, 15) | |

| 7 | Abdominal distension | Dumping subscale (items 22, 23, 25) | |

| 8 | Eructation | ||

| 9 | Increased flatus | Total symptom score (more than seven subscale) | |

| 10 | Decreased passage of stools | ||

| 11 | Increased passage of stools | ||

| 12 | Loose stools | ||

| 13 | Hard stools | ||

| 14 | Urgent need for defecation | ||

| 15 | Feeling of incomplete evacuation | ||

| 16 | Bile regurgitation | ||

| 17 | Sense of foods sticking | ||

| 18 | Postprandial fullness | ||

| 19 | Early satiation | ||

| 20 | Lower abdominal pains | ||

| 21 | Number and type of early dumping symptoms | ||

| 22 | Early dumping, general symptoms | ||

| 23 | Early dumping, abdominal symptoms | ||

| 24 | Number and type of late dumping symptoms | ||

| 25 | Late dumping symptoms | ||

| Living status | 26 | Ingested amount of food per meal1 | |

| 27 | Ingested amount of food per day1 | ||

| 28 | Frequency of main meals | ||

| 29 | Frequency of additional meals | ||

| 30 | Appetite1 | Quality of ingestion subscale (items 30-32)1 | |

| 31 | Hunger feeling1 | ||

| 32 | Satiety feeling1 | ||

| 33 | Necessity for additional meals | ||

| 34 | Ability for working | ||

| Quality of life | 35 | Dissatisfaction with symptoms | Dissatisfaction with daily life subscale (items 35-37) |

| 36 | Dissatisfaction at the meal | ||

| 37 | Dissatisfaction with working |

| Category | Main outcome measure |

| Symptoms | |

| Subscale | Esophageal reflux subscale |

| Abdominal pain subscale | |

| Meal-related distress subscale | |

| Indigestion subscale | |

| Diarrhea subscale | |

| Constipation subscale | |

| Dumping subscale | |

| Total | Total symptom score |

| Living status | |

| Body weight | Change in body weight (%)1 |

| Meals (amount) | Amount of food ingested per meal (%)1 |

| Necessity of additional meals | |

| Meals (quality) | Quality of ingestion subscale1 |

| Work | Ability for working |

| Quality of life | Dissatisfaction with symptom |

| Dissatisfaction | Dissatisfaction at the meal |

| Dissatisfaction at working | |

| Dissatisfaction with daily life subscale |

The questionnaire was distributed to all patients who underwent gastrectomy for gastric cancer by a doctor or nurse at the time of outpatient treatment. Questionnaires were conducted at 1 mo, 3 mo, 6 mo, 12 mo, and 24 mo after surgery. The most recent questionnaire data collected for each patient was used in this study. The questionnaire was collected and managed by a medical clerk, and the data were blindly scored.

This is a retrospective cohort study. We compared it to a national database of 909 patients with distal gastrectomies and Billroth I reconstructions who completed the PGSAS-37 questionnaire. The primary endpoint of our study was to compare the long-term patient outcomes between the two groups in terms of prevalence of PGS and QOL.

Continuous data are presented as average and standard deviations. Independent-sample t-tests were used to analyze continuous data while χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests were used to assess differences in categorical data. Statistical analysis was performed using the StatMate statistical software program (version V). P < 0.05 was considered significant. Cohen’s d was calculated to determine the effect size. The value of Cohen’s d reflects the effect of each casual variable, with 0.2 to < 0.5 denoting a small but clinically meaningful effect, while 0.5 to < 0.8 and ≥ 0.8 denote medium and large effects, respectively. The PGSAS statistic kit was used to compare our experimental data with Japanese national standard values for the Billroth I method from cases obtained from the PGSAS database.

Table 3 shows the patients’ clinicopathological characteristics. There were 94 patients in the ART group and 909 patients in the PGSAS group. The postoperative observation period was significantly longer in the PGSAS group than in the ART group (40.7 ± 30.7 mo vs 27.1 ± 12.2 mo, respectively; P < 0.001). Age was significantly higher in the ART group than in the PGSAS group (70.0 ± 11.0 vs 61.6 ± 9.1, respectively; P < 0.001). Sex and preoperative body mass index showed no significant differences between the two groups. Patients in the ART group had significantly more advanced-stage cancer than those in the PGSAS group. The mean tumor size was 30.7±15.6 mm in the ART group. Laparoscopic surgery was performed in all cases in the ART group, but in only 45.6% of patients in the PGSAS group. Patients in the PGSAS group had a significantly higher rate of combined resection than those in the ART group.

| ART group | PGSAS group | P value | |

| Number of patients | 94 | 909 | |

| Postoperative period in mo | 27.1 ± 12.2 | 40.7 ± 30.7 | < 0.001 |

| Age in yr | 70.0 ± 11.0 | 61.6 ± 9.1 | < 0.001 |

| Sex | 0.333 | ||

| Male | 57 | 594 | |

| Female | 37 | 311 | |

| Preoperative BMI in kg/m2 | 22.7 ± 3.4 | 22.7 ± 3.0 | 1.000 |

| Stage | < 0.001 | ||

| I | 70 | 909 | |

| II | 16 | 0 | |

| III | 8 | 0 | |

| IV | 0 | 0 | |

| Approach | < 0.001 | ||

| Open | 0 | 489 | |

| Laparoscopic | 94 | 415 | |

| Extent of lymph node dissection (D1 >/D1/D2) | 0.135 | ||

| D1 > | 0 | 4 | |

| D1 | 70 | 586 | |

| D2 | 24 | 319 | |

| Combined resection (absence/presence) | 0.001 | ||

| Absence | 89 | 743 | |

| Presence | 5 | 166 |

Perioperative outcomes are shown in Table 4. The average operative time was 285 min, and the intraoperative blood loss was 21.1 mL. No cases were converted to open surgery. Postoperative complications included Clavien-Dindo ≥ 3 in 3 patients (3.1%), anastomotic leakage in 1 patient (1.0%), and anastomotic bleeding in 2 patients (2.1%). The average postoperative hospital stay was 14.5 d with adjuvant chemotherapy performed in 17 patients (18.1%).

| ART, n = 94 | |

| Operation time in min | 285 ± 84 |

| Intraoperative blood loss in mL | 21.1 ± 16.4 |

| Conversion to open surgery | 0 (0%) |

| Postoperative complication CD ≥ 3 | 3 (3.1%) |

| Anastomotic-related complication | |

| Anastomotic leakage | 1 (1.0%) |

| Anastomotic bleeding | 2 (2.1%) |

| Anastomotic stenosis | 0 (0%) |

| Delayed gastric emptying | 0 (0%) |

| Non-anastomotic-related complication | |

| Pancreatic fistula | 4 (4.2%) |

| Surgical site infection | 4 (4.2%) |

| Pneumoniae | 1 (1.0%) |

| Postoperative hospital stay in day | 14.5 ± 14.9 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 17 (18.1%) |

| Adjuvant radiation therapy | 0 (0%) |

A total of 17 main outcomes in three categories (symptoms, living status, and QOL) are shown in Tables 5 and 6, along with the results of the univariate analysis comparing the ART and the PGSAS groups. For the symptoms category, patients in the ART group had significantly lower scores (indicating a better physical condition) in all symptom subscales (esophageal reflux, abdominal pain, meal-related distress, indigestion, diarrhea, constipation, and dumping) and in the total symptoms score (1.6 ± 0.4 vs 2.0 ± 0.7; P < 0.001). Regarding the living status category, the loss of body weight was marginally greater for the ART group than the PGSAS group, (-9.3% vs -7.9%; P = 0.054). The ingested amount of food per meal was statistically lower (indicating a worse physical condition) in the ART group compared to the PGSAS group (6.3 ± 1.9 vs 7.1 ± 2.0; P < 0.001). Although the need for additional meals was not different between the two groups, the quality of ingestion subscale was significantly lower in the ART group compared to the PGSAS group (3.3 ± 1.0 vs3.8 ± 0.9; P < 0.001). Regarding the QOL category, the ART group was significantly lower (indicating a better physical condition) in the subscale of dissatisfaction with symptoms, meals, and daily life (except for the work related item). Furthermore, almost the same results were obtained if the same eligible patient criteria for PGSAS was applied (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2).

| ART group, n = 94 | PGSAS group, n = 909 | Cohen’s d | P value | ||||

| mean | SD | mean | SD | ||||

| Symptom | Esophageal reflux subscale | 1.4 | 0.6 | 1.7 | 0.8 | 0.30 | < 0.001 |

| Abdominal pain subscale | 1.5 | 0.5 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 0.26 | 0.003 | |

| Meal-related distress subscale | 1.7 | 0.7 | 2.1 | 0.9 | 0.35 | < 0.001 | |

| Indigestion subscale | 1.6 | 0.6 | 2.0 | 0.8 | 0.43 | < 0.001 | |

| Diarrhea subscale | 1.8 | 0.7 | 2.1 | 1.1 | 0.27 | 0.001 | |

| Constipation subscale | 1.9 | 0.7 | 2.2 | 1.0 | 0.32 | < 0.001 | |

| Dumping subscale | 1.5 | 0.7 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 0.41 | < 0.001 | |

| Total symptoms score | 1.6 | 0.4 | 2.0 | 0.7 | 0.45 | < 0.001 | |

| ART group, n = 94 | PGSAS group, n = 909 | ||||||

| mean | SD | mean | SD | Cohen’s d | P value | ||

| Living status | Change in body weight (%)1 | -9.3 | 6.4 | -7.9 | 8.1 | 0.17 | 0.054 |

| Amount of food ingested per meal (%)1 | 6.3 | 1.9 | 7.1 | 2.0 | 0.41 | < 0.001 | |

| Necessity of additional meals | 1.8 | 0.7 | 1.9 | 0.8 | 0.00 | 0.977 | |

| Quality of ingestion subscale1 | 3.3 | 1.0 | 3.8 | 0.9 | 0.52 | < 0.001 | |

| Ability for working | 1.8 | 0.9 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 0.13 | 0.261 | |

| Quality of life | Dissatisfaction with symptoms | 1.6 | 0.7 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 0.21 | 0.022 |

| Dissatisfaction during meals | 1.8 | 0.9 | 2.2 | 1.1 | 0.29 | 0.004 | |

| Dissatisfaction during work | 1.6 | 0.7 | 1.7 | 0.9 | 0.03 | 0.774 | |

| Dissatisfaction with daily life subscale | 1.7 | 0.6 | 1.9 | 0.8 | 0.21 | 0.016 | |

This is the first report to evaluate PGS and QOL after a TLDG reconstructed with the novel Billroth I method of ART. Importantly, we compared our results to patients from the Japanese national PGSAS study who did not receive ART. We analyzed PGS and QOL in patients who did and did not receive an ART and found that ART was beneficial. This is important because in Japan a distal gastrectomy is the most commonly performed surgical procedure for gastric cancer.

Billroth I is our preferred post-distal gastrectomy reconstruction method because of its technical simplicity and its restoration of normal anatomy[12]. Our patient questionnaire regarding reconstruction methods after distal gastrectomies in Japan showed that Billroth I was selected as the first choice in 77% of Japanese institutions[13]. In recent years, the number of laparoscopic gastrectomies performed in Japan has dramatically increased, resulting in the publication of multiple reports on various reconstruction techniques[14-17]. However, all of these reported techniques are technically challenging, requiring a certain degree of skill and experience and are associated with complications, such as obstruction due to torsion or stenosis at the anastomotic site.

In 2013, we developed ART as a simpler reconstruction technique after TLDG and currently utilize it for all Billroth I reconstruction methods. Importantly, we also reported a low rate of anastomotic-related complications in the short-term after surgery[6]. There was a concern, however, that in the long-term, there would be a high prevalence of esophageal reflux and dumping symptoms because of the large rectangular anastomosis. Therefore, we evaluated long-term PGS and QOL after ART using the PGSAS-37 questionnaire and analyzed patients’ postoperative functions in comparison to patients in a national database who did not receive ART. The PGSAS questionnaire, used by the national database, is designed specifically to evaluate functional parameters after gastrectomy. It is also freely accessible and is highly versatile since it observes a patient’s condition during daily routine medical care.

Unexpectedly, patients in the ART group fared significantly better in all symptom subscales (esophageal reflux, abdominal pain, meal-related distress, ingestion, diarrhea, constipation, dumping) and in the total symptom scores than the patients in the PGSAS group. Symptoms such as regurgitation and dumping, presumably due to the large anastomosis, were significantly fewer than the national average. This result suggests that ART may be beneficial in reducing these symptoms after gastrectomy. It is not clear why the symptoms subscale and the total score categories both improved. Postoperative anastomotic complications cause a variety of complaints, so our low anastomotic complication rates associated with ART may have contributed to our better PGSAS-37 scores than the national average. Moreover, the reason for this may not only be due to the anastomosis technique but also due to the fact that patients received postoperative continuous nutritional guidance (especially avoiding overeating), ready treatment for any complaint, life guidance as well as psychiatric care. At the very least, this study shows that the large rectangular anastomosis, which is a characteristic of ART, does not cause various complaints.

Focusing on the category of living status, the rate of weight loss in patients was marginally greater in the ART group than observed nationally (P = 0.054). Since the data suggest no additional meals consumed, a smaller amount of food per meal in the ART group may be one of the causes of weight loss. Another reason may be related to the shorter length of the postoperative observation period in our study. The average postoperative observation period was 40.7 mo in patients in the national PGSAS database but only 27.1 mo in patients with ART. In addition, the ART group included 17 patients (18.1%) who received postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy, which is also a factor that can lead to weight loss.

There are several reports on the relationship between PGS and the size of the gastric remnant after a distal gastrectomy with a Billroth I reconstruction. Nomura et al[18] reported that in cases of early gastric cancer patients who maintained half of their gastric remnant showed improved food intake, little postoperative weight loss, and few abdominal symptoms, such as diarrhea and abdominal pain, compared to those who only had one-third of their gastric remnant after a distal gastrectomy with a Billroth I reconstruction. On the other hand, there are reports that there is no relationship between the size of the gastric remnant and weight loss[19].

Japanese gastric cancer guidelines recommend at least two-thirds of the stomach be removed during a distal gastrectomy. We also follow the Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines and perform a complete gastric dissection. Misawa et al[19] evaluated PGS with and without a Kocher maneuver during distal gastrectomy with a Billroth I reconstruction. They reported that the Kocher maneuver resulted in poor PGSAS scores in the quality of ingestion subscale, which evaluates appetite, hunger, and satiety. We found the same result in our study. ART also slightly mobilizes the duodenum during reconstruction, although not to the same extent as a Kocher maneuver. This may be one of the reasons why this aspect of the PGSAS score in the quality of ingestion subscale was worse than the national average. The superior score for patients in the ART group, for the subscales of dissatisfaction with symptoms, diet, and with daily life, indicates that patients are in good shape physically. This also suggests that the lack of ART post-gastrectomy symptoms contributes to maintaining a good QOL on a daily basis. It is difficult to conclude that the infrequency of post-gastrectomy symptoms was due to an anastomosis technique alone but may also reflect appropriate decision making regarding the type of surgical procedure as well as the attentive postoperative management.

This study has several limitations. Specifically, this was a retrospective study in which there were substantial differences between the two groups making some direct comparisons problematic. For example, it is not possible to accurately match patients’ preoperative physical conditioning. Also, since the data published by the PGSAS database are limited, it is again not possible to analyze certain variables that may have impacted outcome. However, almost the same results were obtained if the same eligible patient criteria for PGSAS were applied (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Further prospective research is needed to examine the effects of preoperative factors, including age, sex, body mass index, stage, etc. on PGS and QOL. Another limitation is that it was difficult to provide a rational explanation for all results. PGS varies widely among individuals and is influenced by a variety of physical and functional factors. There have been no studies of a specific Billroth I technique for TLDG that have examined as many symptoms as in this study. In particular, chronological changes are thought to be the most important issue in evaluating a patient’s QOL after gastrectomy. However, we mainly focused on a certain variable, QOL, at the average postoperative observation period of 27.1 mo after gastrectomy. Kobayashi et al[20] reported that patients rarely had any subsequent changes in their QOL more than 1 year after gastrectomy. The average observation period in our study is, by definition, appropriate. At present, PGSAS-45, which is PGSAS plus SF-8, is often used for QOL evaluations after gastrectomy. SF-8 was not measured in this study, and further follow-up studies are needed with this instrument.

From this retrospective evaluation, we concluded that the results of an ART reconstruction produced beneficial long-term results with regards to PGS and postoperative QOL. Further investigation involving a larger number of patients comparing ART with other anastomotic techniques and evaluating long-term patient outcomes is needed to validate the benefits of ART reconstruction after TLDG.

For total laparoscopic distal gastrectomies for gastric cancer, the reconstruction method is critical to the clinical outcome of the procedure. We originally reported the augmented rectangle technique (ART) as a reconstruction option for total laparoscopic Billroth I reconstructions. Yet, little is known about its effect on long-term outcomes, specifically the incidence of postgastrectomy syndrome (PGS) and its impact on quality of life (QOL).

Reducing the prevalence of PGS and improving the QOL after gastrectomy for gastric cancer patients has become an important technical challenge for surgeons. ART shows good short-term results, but long-term results in terms of PGS and quality of life should be reported.

To analyze PGS and QOL after ART using the Postgastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Scale-37 (PGSAS-37) questionnaire.

At Juntendo University, 94 patients who underwent ART for Billroth I reconstruction with total laparoscopic distal gastrectomies for gastric cancer between July 2016 to March 2020 completed questionnaires. Multidimensional analysis was performed comparing those 94 ART cases from our institution (ART group) to 909 distal gastrectomy cases with a Billroth I reconstruction from other Japanese institutions who also completed the PGSAS as part of a larger national database (PGSAS group).

Patients in the ART group had significantly better total symptom scores in all the symptom subscales (esophageal reflux, abdominal pain, meal-related distress, indigestion, diarrhea, constipation, and dumping). The loss of body weight was marginally greater for those in the ART group than in the PGSAS group (-9.3% vs -7.9%; P = 0.054). The ART group scored significantly lower in their dissatisfaction of ongoing symptoms, during meals, and with daily life.

The use of ART for Billroth I reconstruction produced beneficial long-term results with regards to PGS and QOL in patients undergoing total laparoscopic distal gastrectomies for gastric cancer.

Further investigation of the mechanism underlying the usefulness of ART in terms of PGS and QOL is needed. Prospective studies are also needed on the involvement of factors other than the anastomotic method.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D, D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cai ZL, Luo TH S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Davis JL, Ripley RT. Postgastrectomy Syndromes and Nutritional Considerations Following Gastric Surgery. Surg Clin North Am. 2017;97:277-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Bolton JS, Conway WC 2nd. Postgastrectomy syndromes. Surg Clin North Am. 2011;91:1105-1122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Carvajal SH, Mulvihill SJ. Postgastrectomy syndromes: dumping and diarrhea. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1994;23:261-279. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Kim AR, Cho J, Hsu YJ, Choi MG, Noh JH, Sohn TS, Bae JM, Yun YH, Kim S. Changes of quality of life in gastric cancer patients after curative resection: a longitudinal cohort study in Korea. Ann Surg. 2012;256:1008-1013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Karanicolas PJ, Graham D, Gönen M, Strong VE, Brennan MF, Coit DG. Quality of life after gastrectomy for adenocarcinoma: a prospective cohort study. Ann Surg. 2013;257:1039-1046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Fukunaga T, Ishibashi Y, Oka S, Kanda S, Yube Y, Kohira Y, Matsuo Y, Mori O, Mikami S, Enomoto T, Otsubo T. Augmented rectangle technique for Billroth I anastomosis in totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:4011-4016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nakada K, Ikeda M, Takahashi M, Kinami S, Yoshida M, Uenosono Y, Kawashima Y, Oshio A, Suzukamo Y, Terashima M, Kodera Y. Characteristics and clinical relevance of postgastrectomy syndrome assessment scale (PGSAS)-45: newly developed integrated questionnaires for assessment of living status and quality of life in postgastrectomy patients. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:147-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:101-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2390] [Cited by in RCA: 2870] [Article Influence: 205.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18532] [Cited by in RCA: 24762] [Article Influence: 1179.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Svedlund J, Sjödin I, Dotevall G. GSRS--a clinical rating scale for gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and peptic ulcer disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:129-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 884] [Cited by in RCA: 1034] [Article Influence: 27.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wiklund IK, Junghard O, Grace E, Talley NJ, Kamm M, Veldhuyzen van Zanten S, Paré P, Chiba N, Leddin DS, Bigard MA, Colin R, Schoenfeld P. Quality of Life in Reflux and Dyspepsia patients. Psychometric documentation of a new disease-specific questionnaire (QOLRAD). Eur J Surg. 1998;583:41-49. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Kim BJ, O'Connell T. Gastroduodenostomy after gastric resection for cancer. Am Surg. 1999;65:905-907. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Kumagai K, Shimizu K, Yokoyama N, Aida S, Arima S, Aikou T; Japanese Society for the Study of Postoperative Morbidity after Gastrectomy. Questionnaire survey regarding the current status and controversial issues concerning reconstruction after gastrectomy in Japan. Surg Today. 2012;42:411-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kanaya S, Gomi T, Momoi H, Tamaki N, Isobe H, Katayama T, Wada Y, Ohtoshi M. Delta-shaped anastomosis in totally laparoscopic Billroth I gastrectomy: new technique of intraabdominal gastroduodenostomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;195:284-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 235] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tanimura S, Higashino M, Fukunaga Y, Takemura M, Nishikawa T, Tanaka Y, Fujiwara Y, Osugi H. Intracorporeal Billroth 1 reconstruction by triangulating stapling technique after laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2008;18:54-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ikeda T, Kawano H, Hisamatsu Y, Ando K, Saeki H, Oki E, Ohga T, Kakeji Y, Tsujitani S, Kohnoe S, Maehara Y. Progression from laparoscopic-assisted to totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy: comparison of circular stapler (i-DST) and linear stapler (BBT) for intracorporeal anastomosis. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:325-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Byun C, Cui LH, Son SY, Hur H, Cho YK, Han SU. Linear-shaped gastroduodenostomy (LSGD): safe and feasible technique of intracorporeal Billroth I anastomosis. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:4505-4514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Nomura E, Lee SW, Bouras G, Tokuhara T, Hayashi M, Hiramatsu M, Okuda J, Tanigawa N. Functional outcomes according to the size of the gastric remnant and type of reconstruction following laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:279-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Misawa K, Terashima M, Uenosono Y, Ota S, Hata H, Noro H, Yamaguchi K, Yajima H, Nitta T, Nakada K. Evaluation of postgastrectomy symptoms after distal gastrectomy with Billroth-I reconstruction using the Postgastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Scale-45 (PGSAS-45). Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:675-681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kobayashi D, Kodera Y, Fujiwara M, Koike M, Nakayama G, Nakao A. Assessment of quality of life after gastrectomy using EORTC QLQ-C30 and STO22. World J Surg. 2011;35:357-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |