Published online Dec 27, 2022. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v14.i12.1411

Peer-review started: June 13, 2022

First decision: July 14, 2022

Revised: July 28, 2022

Accepted: October 4, 2022

Article in press: October 4, 2022

Published online: December 27, 2022

Processing time: 197 Days and 2.7 Hours

With the emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in late 2019 in Wuhan, China, liver injury in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) due to SARS-CoV-2 infection has been regularly reported in the literature. There are a growing number of publications describing the occurrence of secondary sclerosing cholangitis (SSC) after SARS-CoV-2 infection in various cases. We present a case of sudden onset SSC in a critically ill patient (SSC-CIP) following COVID-19 infection who was previously healthy.

A 33-year old female patient was admitted to our University Hospital due to increasing shortness of breath. A prior rapid antigen test showed a positive result for SARS-CoV-2. The patient had no known preexisting conditions. With rapidly increasing severe hypoxemia she required endotracheal intubation and developed the need for veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in a setting of acute respiratory distress syndrome. During the patient´s 154-d stay in the intensive care unit and other hospital wards she underwent hemodialysis and extended polypharmaceutical treatment. With increasing liver enzymes and the development of signs of cholangiopathy on magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) as well as endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), the clinical setting was suggestive of SSC. At an interdisciplinary meeting, the possibility of orthotopic liver transplantation and additional kidney transplantation was discussed due to the constant need for hemodialysis. Following a deterioration in her general health and impaired respiratory function with a reduced chance of successful surgery and rehabilitation, the plan for transplantation was discarded. The patient passed away due to multiorgan failure.

SSC-CIP seems to be a rare but serious complication in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection, of which treating physicians should be aware. Imaging with MRCP and/or ERCP seems to be indicated and a valid method for early diagnosis. Further studies on the effects of early and late SSC in (post-) COVID-19 patients needs to be performed.

Core Tip: Secondary sclerosing cholangitis in critically ill patients is an important complication in patients requiring intensive care treatment. With the ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic we will see increasing complications regarding the liver and the biliary system. Our case report hopes to aid other surgeons, radiologists and intensive care physicians in their decision making.

- Citation: Steiner J, Kaufmann-Bühler AK, Fuchsjäger M, Schemmer P, Talakić E. Secondary sclerosing cholangitis in a young COVID-19 patient resulting in death: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 2022; 14(12): 1411-1417

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v14/i12/1411.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v14.i12.1411

With the emergence of an unknown respiratory virus of the corona group in late 2019 in Wuhan, China, an undetected spread of the newly discovered severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has been observed, which was declared a pandemic by the WHO in March 2020.

Common signs of SARS-CoV-2 infection include flu-like symptoms, dyspnea, fatigue, anosmia, headache and fever, with potentially life-threatening acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) developing in some cases, requiring intensive medical care. During this ongoing crisis, and due to the nature of a novel virus infection, the scientific community has been able to identify a wide range of different symptoms and features attributable to the later and rarer hyperinflammatory phase in some cases. In particular, the diffuse inflammatory phase appears to be a multiorgan problem that is not limited to the lungs or upper respiratory tract[1,2].

Liver injury in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection has been regularly reported in the literature during the course of the ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. The occurrence of elevated and abnormal liver parameters has been demonstrated in 14% to 76% of patients. Recent case reports and series have investigated and discussed the probability of increased risk for permanent damage to the hepatobiliary system[1-4].

There are a growing number of publications in the literature describing the occurrence of secondary sclerosing cholangitis (SSC) after SARS-CoV-2 infection in various cases, particularly after severe COVID-19-associated ARDS with a reported incidence of up to 2.6% of intensive care unit (ICU) patients[5].

We report the sudden onset of SSC in a critically ill patient (SSC-CIP) following severe COVID-19 infection ultimately resulting in death.

A 33-year-old female patient was admitted to our University Hospital by emergency medical services (EMS) due to shortness of breath.

According to her relatives, she had been feeling ill for a week, and her general health deteriorated rapidly and she developed a high fever. She had tested positive for the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) 7 d prior to admission.

The patient had an elevated body mass index of 34 (1.68 m/95 kg), and was previously healthy with no preexisting conditions, particularly no known liver damage or respiratory problems.

No relevant personal or family history was recorded.

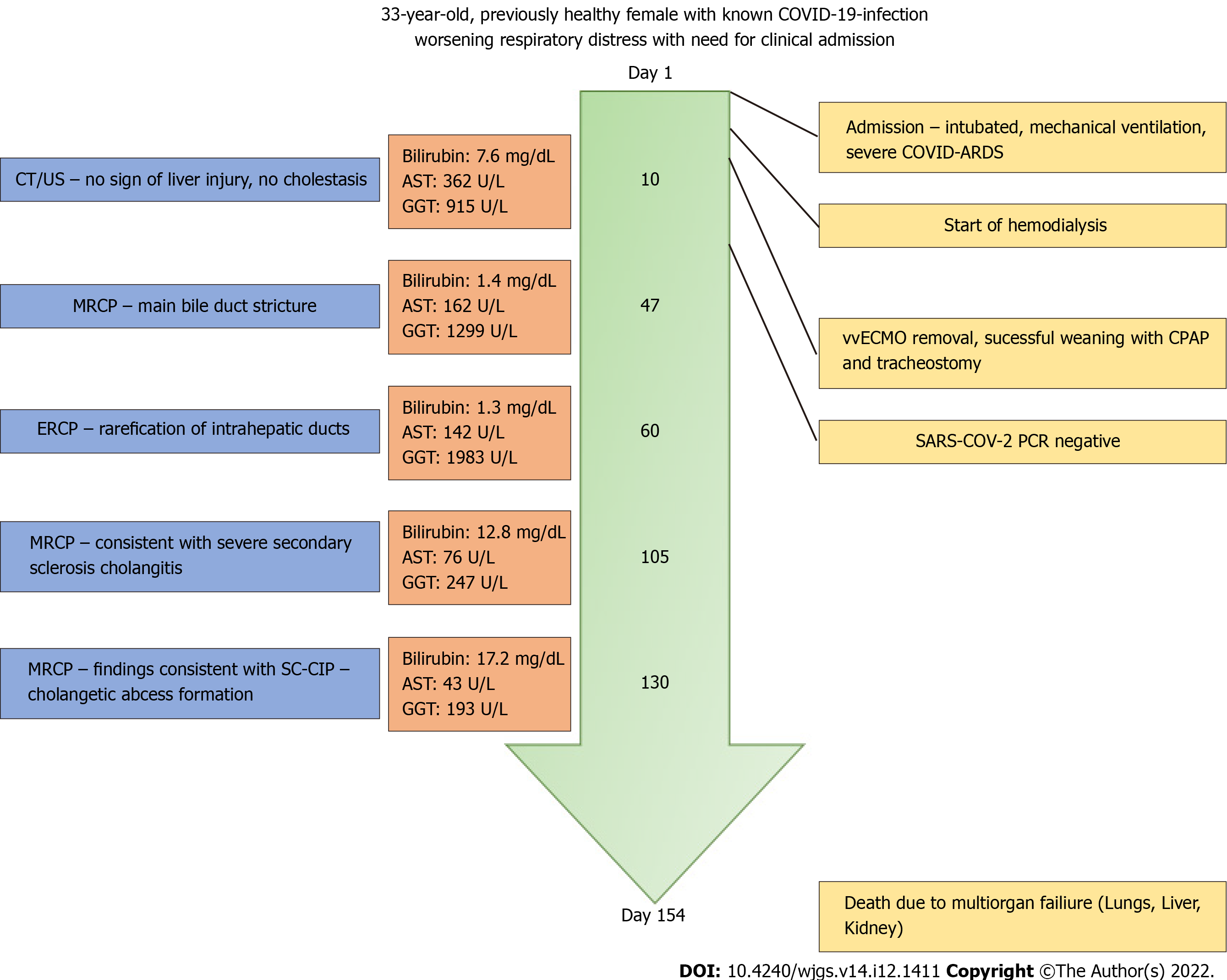

On arrival of the EMS, respiratory function was already compromised by severe hypoxemia requiring endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation onsite, which did not improve on admission with high ventilation pressure and poor O2 saturation. Veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (vvECMO) was administered, which provided acceptable oxygenation in the setting of severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (COVID-19-ARDS) with a persistent need of continuous catecholamines. During the patient´s 154-d stay in the ICU and other hospital wards, hemodialysis was initiated on day 4, ECMO was removed on day 14, and successful weaning was achieved on day 15 (Figure 1).

During the patient’s treatment for severe COVID-19-associated ARDS in the ICU, impaired liver function with elevated liver and cholestasis parameters (bilirubin, gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) and alkaline phosphatase (AP)) was detected. Due to the polypharmaceutical therapy regime with additional ECMO treatment, toxic/ischemic liver injury was initially suspected.

Following ECMO removal and reduction of sedation (particularly ketamine), elevated liver enzymes persisted indicating SSC-CIP. Laboratory parameters continued to show slightly elevated bilirubin (1.4 mg/dL), GGT (1299 U/L), AP (1883 U/L), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (162 U/L) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (119 U/L).

Treatment for SSC-CIP with Ursofalk® 1000 mg was initiated.

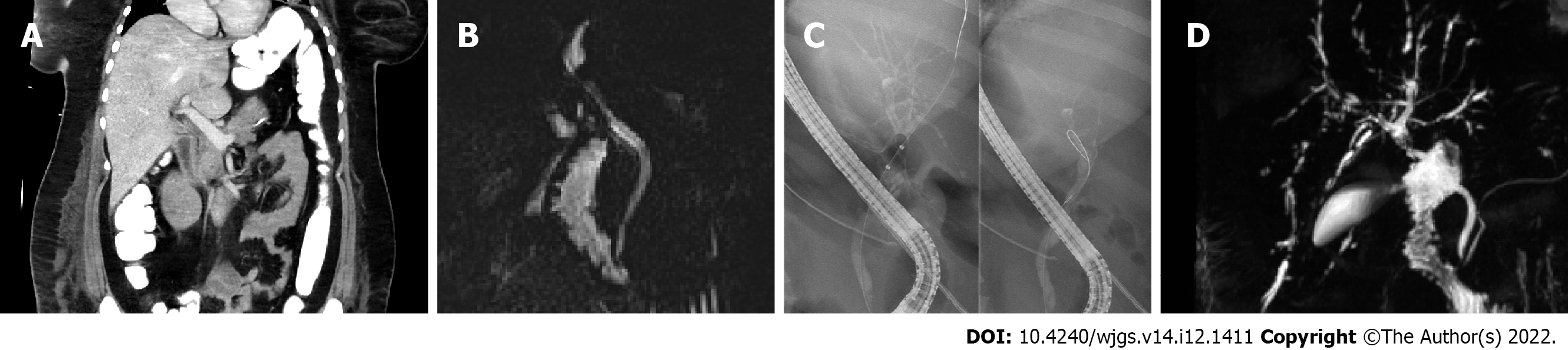

A computed tomography of the abdomen on day 10 showed no signs of parenchymal damage or cholestasis (Figure 2A).

After prolonged treatment in the ICU, the patient underwent magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) on day 47 after admission, which revealed no signs of liver injury or intrahepatic cholestasis but mild stenosis of the distal common bile duct (CBD) and suspected stricture of prepapillary CBD main.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was performed on day 60 and showed rarefication of intrahepatic bile ducts, suggesting SSC-CIP (Figure 2C). An additional MRCP follow-up on day 105 after the initial admission confirmed SSC-CIP with worsening of multiple diffuse stricture of the CBD and entire intrahepatic biliary tree compared to the initial MRCP. Round T2-signal changes with restricted diffusion were identified, suggestive of additional cholangetic abscess formation (Figure 2B and D).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) follow-up on day 129 depicted progressive encapsulated intrahepatic fluid accumulation with restricted diffusion and rim-contrast enhancement, associated with progressive intrahepatic abscess.

In the following weeks, our patient suffered from persistent and undulating elevated inflammatory parameters [especially C-reactive protein (CRP), peak 217 mg/L] and overall worsening of her general condition. Due to renal failure, hemodialysis was performed three times a week. Liver parameters remained elevated (e.g., bilirubin peak 17.29 mg/dL on day 139).

At an interdisciplinary meeting, the possibility of orthotopic liver transplantation and additional kidney transplantation was discussed due the constant need for hemodialysis. As a result of a deterioration in general health and impaired respiratory function with a reduced chance of successful surgery and rehabilitation, the plan for transplantation was discarded.

Due to the rapid acceleration and worsening of SSC-CIP, we strongly suspected the presence of post-COVID-19 cholangiopathy with the development of SSC-CIP.

Throughout the ICU period, she was treated according to guidelines, with additional remdesivir, a nucleotide analogue prodrug with broad-spectrum antiviral activity and Convalescent Plasma Transfusion as well as various treatments with additional antibiotics, including Noxafil®, Pi

On day 154, our patient passed away due to organ failure involving the respiratory system, kidneys and liver. No autopsy was performed.

SSC-CIP is a recently included form of cholestatic liver disease in a patient population undergoing prolonged intensive care for various reasons without known hepatic or biliary disease. It is usually the result of trauma, burn injuries, or major surgical procedures such as cardiothoracic surgery or transplantation procedures[6,7].

While up to 60% of SSC-CIP patients survive to ICU discharge, the need for later transplantation is high at up to 20%. One-year survival without transplantation has been reported to be 55%[8].

SSC-CIP is thought to be the result of direct damage to cholangiocytes, either by ischemia/hypoxia or by toxic bile with changes in bile composition or by infection. There is no single predisposing or causative factor for the development of SSC-CIP. Severe hypotension seems to directly cause ischemic bile duct damage and contribute to it by altering hepatobiliary transporters. Sepsis and microcirculatory disturbances have also been attributed to transporter alteration[9].

Liver damage resulting from SARS-CoV-2 infection has been described in the literature. Throughout the pandemic, many publications have described a close association between SARS-CoV-2 and elevated liver enzymes in the early stages of infection and liver parenchymal injury. Most authors theorize that increased angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor expression in hepatocytes and even more in cholangiocytes leads to direct damage of cells by the virus, possibly causing cell destruction[2,10,11].

Additional changes in microvascular steatosis due to the thrombogenic characteristics of the novel coronavirus 19 appear to play a role in this parenchymal damage[10,11].

As described by Kaltschmidt et al[12], SARS-CoV-2 replicates in the liver parenchyma and is secreted into the bile ducts, which in combination with platelet activation and parenchymal injury appears to result in direct damage to the biliary system. The accompanying necrosis with the development of stenosis seem to directly promote the occurrence of sclerosing cholangitis[12].

SSC, as in our case, is usually diagnosed by imaging techniques such as ERCP and MRI. Distinguishing features include strictures and stenosis as well as newly developed dilations of intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts[13].

While ERCP offers the possibility of direct intervention such as stent placement, MRI, particularly MRCP, is a noninvasive modality for early diagnosis and follow-up, widely available in Western countries. With protocols starting at 15 min, it is also within a reasonable timeframe for monitoring intensive care patients.

Although our patient was ultimately not a candidate for transplantation, there are a growing number of case reports showing promising results with orthotopic liver transplantation for SSC-CIP following COVID-19[14,15].

As mentioned above SSC-CIP can occur due to various underlying conditions including pharmacological toxicity, prolonged intensive care treatment and interventions. In our case, the rapid onset of liver parameter changes with early elevated GGT/AST compared with relatively low bilirubin, followed by subsequent increasing bilirubin levels and textbook appearance on MRCP strongly suggest a close correlation between SSC-CIP and SARS-CoV-2 infection. In our case, this was most likely due to recently described post-COVID-19 cholangiopathy, in which early cholangiocytic injury leads to late stenosis and sclerosis, ultimately resulting in death. Differential diagnoses of the cause could include the mentioned prolonged intensive treatment, which seemed in our experience less likely.

Due to the lack of autopsy or biopsy, the major limitation in our case is the lack of confirmation of histopathological findings suggestive of SSC-CIP with liver parenchymal changes associated with viral damage, such as the presence of cytokeratin 7 metaplasia of periportal hepatocytes, compared with SCC with a possible other cause, most likely caused by drugs - due to prolonged mechanical ventilation and sedation.

Despite its limitations, our case fits other cases and case series in the current literature and demonstrates the importance of early and regular evaluation of cholestatic parameters. SSC-CIP seems to be a rare but serious complication in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection, of which treating physicians should be aware.

Imaging with MRCP and/or ERCP seems to be indicated and a valid method for early diagnosis. Although our case resulted in death as the patient was unfit for transplantation, liver transplantation seems to be a promising treatment in severe cases.

Given the still unknown long time span after complications in a post-pandemic medical world, the awareness of secondary liver injury and cholestatic damage should be monitored and further studies on the effects of early and late SSC in (post-) COVID-19 patients need to be performed.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Radiology, nuclear medicine and medical Imaging

Country/Territory of origin: Austria

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Barve P, United States; Saito H, Japan; Solanki SL, India S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Gong ZM

| 1. | Zhong P, Xu J, Yang D, Shen Y, Wang L, Feng Y, Du C, Song Y, Wu C, Hu X, Sun Y. COVID-19-associated gastrointestinal and liver injury: clinical features and potential mechanisms. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5:256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 28.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Sharma A, Jaiswal P, Kerakhan Y, Saravanan L, Murtaza Z, Zergham A, Honganur NS, Akbar A, Deol A, Francis B, Patel S, Mehta D, Jaiswal R, Singh J, Patel U, Malik P. Liver disease and outcomes among COVID-19 hospitalized patients - A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Hepatol. 2021;21:100273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Fix OK, Hameed B, Fontana RJ, Kwok RM, McGuire BM, Mulligan DC, Pratt DS, Russo MW, Schilsky ML, Verna EC, Loomba R, Cohen DE, Bezerra JA, Reddy KR, Chung RT. Clinical Best Practice Advice for Hepatology and Liver Transplant Providers During the COVID-19 Pandemic: AASLD Expert Panel Consensus Statement. Hepatology. 2020;72:287-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 280] [Cited by in RCA: 422] [Article Influence: 84.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Li Y, Xiao SY. Hepatic involvement in COVID-19 patients: Pathology, pathogenesis, and clinical implications. J Med Virol. 2020;92:1491-1494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Meersseman P, Blondeel J, De Vlieger G, van der Merwe S, Monbaliu D; Collaborators Leuven Liver Transplant program. Secondary sclerosing cholangitis: an emerging complication in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47:1037-1040. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gupta A, Madhavan MV, Sehgal K, Nair N, Mahajan S, Sehrawat TS, Bikdeli B, Ahluwalia N, Ausiello JC, Wan EY, Freedberg DE, Kirtane AJ, Parikh SA, Maurer MS, Nordvig AS, Accili D, Bathon JM, Mohan S, Bauer KA, Leon MB, Krumholz HM, Uriel N, Mehra MR, Elkind MSV, Stone GW, Schwartz A, Ho DD, Bilezikian JP, Landry DW. Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26:1017-1032. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2419] [Cited by in RCA: 2044] [Article Influence: 408.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 7. | Esposito I, Kubisova A, Stiehl A, Kulaksiz H, Schirmacher P. Secondary sclerosing cholangitis after intensive care unit treatment: clues to the histopathological differential diagnosis. Virchows Arch. 2008;453:339-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kulaksiz H, Heuberger D, Engler S, Stiehl A. Poor outcome in progressive sclerosing cholangitis after septic shock. Endoscopy. 2008;40:214-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Leonhardt S, Veltzke-Schlieker W, Adler A, Schott E, Eurich D, Faber W, Neuhaus P, Seehofer D. Secondary Sclerosing Cholangitis in Critically Ill Patients: Clinical Presentation, Cholangiographic Features, Natural History, and Outcome: A Series of 16 Cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e2188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chan HL, Kwan AC, To KF, Lai ST, Chan PK, Leung WK, Lee N, Wu A, Sung JJ. Clinical significance of hepatic derangement in severe acute respiratory syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:2148-2153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zhao B, Ni C, Gao R, Wang Y, Yang L, Wei J, Lv T, Liang J, Zhang Q, Xu W, Xie Y, Wang X, Yuan Z, Zhang R, Lin X. Recapitulation of SARS-CoV-2 infection and cholangiocyte damage with human liver ductal organoids. Protein Cell. 2020;11:771-775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 268] [Cited by in RCA: 311] [Article Influence: 62.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kaltschmidt B, Fitzek ADE, Schaedler J, Förster C, Kaltschmidt C, Hansen T, Steinfurth F, Windmöller BA, Pilger C, Kong C, Singh K, Nierhaus A, Wichmann D, Sperhake J, Püschel K, Huser T, Krüger M, Robson SC, Wilkens L, Schulte Am Esch J. Hepatic Vasculopathy and Regenerative Responses of the Liver in Fatal Cases of COVID-19. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:1726-1729.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kim HJ, Park MS, Son JW, Han K, Lee JH, Kim JK, Paik HC. Radiological patterns of secondary sclerosing cholangitis in patients after lung transplantation. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2019;44:1361-1366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lee A, Wein AN, Doyle MBM, Chapman WC. Liver transplantation for post-COVID-19 sclerosing cholangitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Durazo FA, Nicholas AA, Mahaffey JJ, Sova S, Evans JJ, Trivella JP, Loy V, Kim J, Zimmerman MA, Hong JC. Post-Covid-19 Cholangiopathy-A New Indication for Liver Transplantation: A Case Report. Transplant Proc. 2021;53:1132-1137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |