Published online Sep 27, 2021. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v13.i9.1000

Peer-review started: February 21, 2021

First decision: May 13, 2021

Revised: May 22, 2021

Accepted: August 2, 2021

Article in press: August 2, 2021

Published online: September 27, 2021

Processing time: 209 Days and 9 Hours

Adjuvant chemotherapy (ACTx) is recommended in rectal cancer patients after preoperative chemoradiotherapy (PCRT), but its efficacy in patients in the early post-surgical stage who have a favorable prognosis is controversial.

To evaluate the long-term survival benefit of ACTx in patients with ypT0–1 rectal cancer after PCRT and surgical resection.

We identified rectal cancer patients who underwent PCRT followed by surgical resection at the Asan Medical Center from 2005 to 2014. Patients with ypT0–1 disease and those who received ACTx were included. The 5-year overall survival (OS) and 5-year recurrence-free survival (RFS) were analyzed according to the status of the ACTx.

Of 520 included patients, 413 received ACTx (ACTx group) and 107 did not (no ACTx group). No significant difference was observed in 5-year RFS (ACTx group, 87.9% vs no ACTx group, 91.4%, P = 0.457) and 5-year OS (ACTx group, 90.5% vs no ACTx group, 86.2%, P = 0.304) between the groups. cT stage was associated with RFS and OS in multivariate analysis [hazard ratio (HR): 2.57, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.07–6.16, P = 0.04 and HR: 2.27, 95%CI: 1.09–4.74, P = 0.03, respectively]. Furthermore, ypN stage was associated with RFS and OS (HR: 4.74, 95%CI: 2.39–9.42, P < 0.00 and HR: 4.33, 95%CI: 2.20–8.53, P < 0.00, respectively), but only in the radical resection group.

Oncological outcomes of patients with ypT0–1 rectal cancer who received ACTx after PCRT showed no improvement, regardless of the radicality of resection. Further trials are needed to evaluate the efficacy of ACTx in these group of patients.

Core Tip: Adjuvant chemotherapy (ACTx) is administered based on the clinical stage of rectal cancer after preoperative chemoradiotherapy (PCRT), regardless of post-treatment pathologic stage. Prognosis differs according to post-treatment pathologic stage or regression grade. Adjuvant treatment may be administered based on prognostic influence. Patients with ypT0-1 rectal cancer with favorable oncologic outcomes were included. Since local excision (LE) frequency has increased, ACTx effects in these patients need to be studied. We included patients who underwent LE. ACTx in patients with ypT0-1 rectal cancer after PCRT and LE did not exert benefits in terms of overall survival and recurrence-free survival.

- Citation: Jeon YW, Park IJ, Kim JE, Park JH, Lim SB, Kim CW, Yoon YS, Lee JL, Yu CS, Kim JC. Evaluating the benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with ypT0–1 rectal cancer treated with preoperative chemoradiotherapy. World J Gastrointest Surg 2021; 13(9): 1000-1011

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v13/i9/1000.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v13.i9.1000

The current guidelines recommend the use of adjuvant chemotherapy (ACTx) in patients who have undergone preoperative chemoradiotherapy (PCRT) and surgical resection based on the clinical stage before PCRT[1]. However, the efficacy of ACTx, regardless of the patients’ pathological findings, is controversial[2]. Previous studies have reported an improvement in the oncological outcomes of rectal cancer patients who underwent PCRT, total mesorectal excision (TME), and ACTx[3-5]; the outcomes differed according to the postoperative pathological stage or the tumor regression grade[6,7] rather than the pre-PCRT clinical stage. Therefore, tumor regression grade and post-surgical stage have been considered predictors of oncological outcomes of ACTx[8].

Patients with good response to PCRT have a favorable prognosis, and the 5-year recurrence-free survival (RFS) of patients with yp stage 0 and 1 disease after PCRT is > 90%[9,10]. Considering the risks of ACTx such as toxicity and financial burden[11,12], limited information is available regarding the oncological benefit of ACTx in patients with early yp stage 0 and 1 diseases[13]. Recent studies analyzing the oncological benefit of ACTx in patients who achieved a pathological complete response have reported inconsistent results[14-18]. Therefore, it is imperative to analyze the survival benefit of ACTx in patients in the early post-surgical stage who have a good prognosis. Hence, this study aimed to evaluate the long-term survival benefit of ACTx in patients with ypT0–1 disease after PCRT and surgical resection.

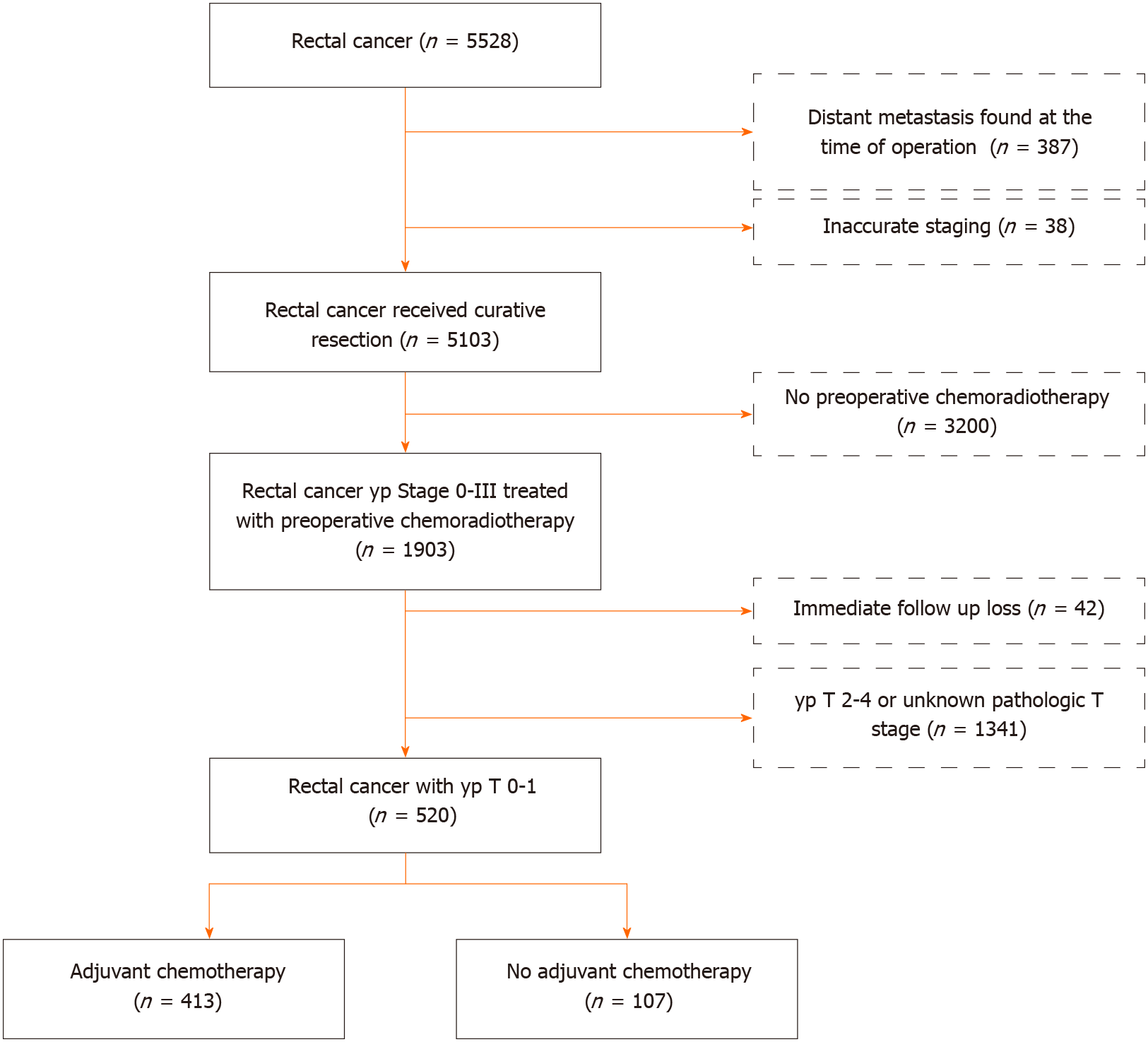

We initially identified 5207 rectal cancer patients who underwent PCRT followed by surgical resection [radical resection or local excision (LE)] between January 2005 and December 2014 at the Asan Medical Center, Seoul, South Korea. Of the patients who underwent PCRT, 42 who were lost to follow-up and 1341 with ypT2–4 or ypTx disease were excluded. Patients who received ACTx postoperatively were categorized into the ACTx group, while those who did not receive ACTx postoperatively were categorized into the no ACTx group (Figure 1). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of (registration No. 2017-1114), which waived the requirement for obtaining an informed consent due to the retrospective nature of the study.

For patients who opted to receive PCRT, a radiation dose of 45–50.4 Gy was delivered in 20–28 fractions (1.8–2.0 per fraction) to a target volume including the primary tumor, perirectal adipose tissue, lateral pelvis, and presacral lymph node (LN) during the PCRT treatment period. Concurrent chemotherapy consisted of either two cycles of intravenous bolus injection of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU, 375 mg/m2/d) and leucovorin (20 mg/m2/d) (FL) or oral administration of capecitabine (825 mg/m2) twice daily. Other agents such as oxaliplatin, TS-1, and temozolomide were used as a combination therapy in some patients.

Surgical resection was performed 6–12 wk after the completion of radiation therapy. Radical surgical resection was performed according to the principles of TME. For the LE of the tumor, transanal LE, transanal minimally invasive surgery, or full thickness excision was performed.

ACTx was recommended in all medically fit patients who underwent PCRT. The recommended adjuvant regimen consisted of four cycles of 5-FU and leucovorin (FL) monthly or six cycles of capecitabine.

All patients underwent postoperative follow-up, which consisted of physical examination, serum carcinoembryonic antigen measurement, chest radiography, and abdominal, pelvic, and chest computed tomography (CT) every 3–6 mo. Most patients underwent colonoscopy between 6 mo and 1 year postoperatively and every 2–3 years thereafter. Recurrence was determined according to the radiological or histopathological findings. Local recurrence was defined as the presence of a suspicious lesion in the areas contiguous to the bed of the primary rectal resection or the site of anastomosis, while distant metastasis was defined as the presence of any recurrence in a distant organ or dissemination to the peritoneal surface. RFS was measured from the date of surgery to the date of detection of the first recurrence or death.

Patients who underwent LE were followed up every 3 mo for the first 1–2 years postoperatively and every 6 mo thereafter. Physical assessment with digital rectal examination and laboratory tests including sigmoidoscopy were performed every 3 mo for the first 1–2 years and every 6 mo for the next 3–4 years for a total of 5 years. Full colonoscopy was performed within 1 year after surgery and every 2–3 years thereafter. Abdominopelvic and chest CT was performed every 6 mo for 5 years.

Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test, while normally distributed continuous data were analyzed using the Student’s t-test. Survival curves were constructed using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using log-rank tests according to the status of ACTx. The associations between the clinical factors and RFS were determined using the Cox proportional hazard regression analysis. Statistical significance was assumed at a level of 5%. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States).

A total of 520 patients were enrolled. The mean (± SD) age was 59.1 ± 10.5) years. Approximately 59.4% patients were men, and 85% patients underwent radical resection. The mean follow-up duration was 71.0 ± 32.6 mo. In the ACTx and no ACTx groups, the proportion of patients with cT3–4 and cN+ disease was higher than that of patients with cT1–2 and cN− disease. The ACTx group had a higher proportion of patients with advanced cT and cN disease compared with the no ACTx group. There was no significant difference in ypT stage between both groups. LN retrievals were evaluated in patients who underwent radical resection. The mean number of examined LNs and proportion of patients with ypN stage were similar in both groups (Table 1).

| Variables | ACTx (n = 413) | No ACTx (n = 107) | P value | |

| Age, mean ± SD, yr | 58 ± 10.1 | 63.4 ± 11.0 | < 0.001 | |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.659 | |||

| Male | 243 (58.8) | 66 (61.7) | ||

| Female | 170 (41.2) | 41 (38.3) | ||

| cT category, n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| cT1–2 | 83 (20.1) | 48 (44.9) | ||

| cT3–4 | 330 (79.9) | 59 (55.1) | ||

| cN category, n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| cN- | 65 (15.7) | 34 (31.8) | ||

| cN+ | 348 (84.3) | 73 (68.2) | ||

| Type of surgery, n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| Radical resection | 378 (91.5) | 64 (59.8) | ||

| Local excision | 35 (8.5) | 43 (40.2) | ||

| Number of examined LNs, mean ± SD1 | 14.7 ± 6.9 | 14.6 ± 6.3 | 0.892 | |

| pT category, n (%) | 0.099 | |||

| ypT0 | 294 (71.2) | 67 (62.6) | ||

| ypTis–1 | 119 (28.8) | 40 (37.4) | ||

| pN category1, n (%) | 0.201 | |||

| ypN0 | 347 (91.8) | 62 (96.9) | ||

| ypN+ | 31 (8.2) | 2 (3.1) | ||

| Lymphovascular invasion, n (%) | 4 (1) | - | 0.339 | |

| Follow-up duration mean ± SD, months | 72.1 ± 33.0 | 66.4 ± 30.3 | 0.105 | |

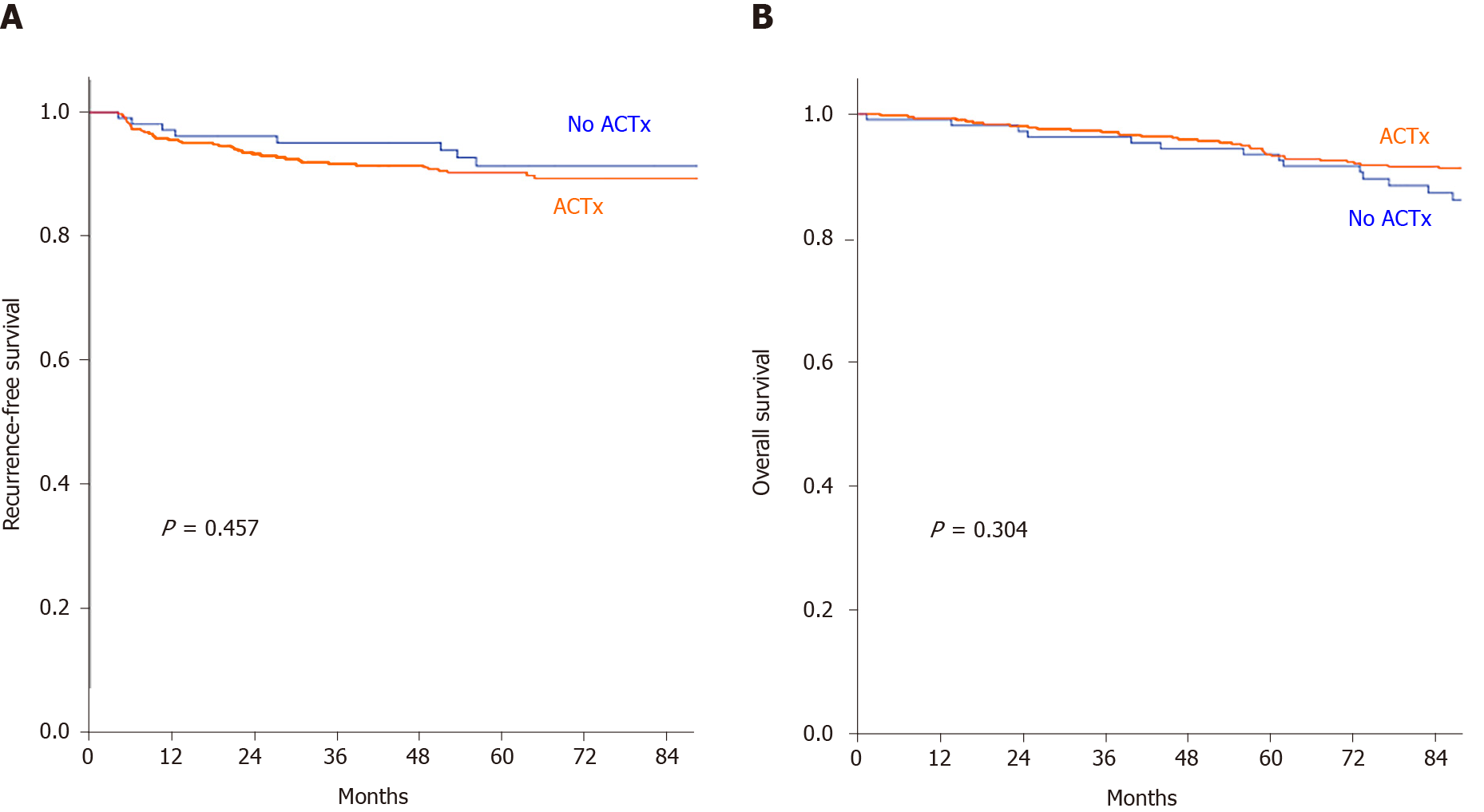

The recurrence rates were significantly different according to the status of ACTx (P = 0.009). The ACTx group had a recurrence rate of 10.4% (43/413), and most patients had distant metastasis (9.7%, 40/43). The most common site of metastasis in the ACTx group was the lung (57.5%). The no ACTx group had a recurrence rate of 7.4%, which was significantly lower than that of the ACTx group (P = 0.009). Distant LNs were the most common site of metastasis in the no ACTx group (Table 2). The 5-year RFS rates in the ACTx and no ACTx groups were 87.9% and 91.4%, respectively (P = 0.457), while the overall survival (OS) rates were 90.5% and 86.2%, respectively (P = 0.304). No significant difference was observed in the RFS and OS between the groups (Figure 2).

| Variables | ACTx (n = 413) | No ACTx (n = 107) | P value | |

| Recurrence, n (%) | 43 (10.4) | 8 (7.4) | ||

| Type of recurrence, n (%) | 0.009 | |||

| Local recurrence | 3 (0.7) | 4 (3.7) | ||

| Distant metastasis | 40 (9.7) | 4 (3.7) | ||

| Sites of distant metastasis1, n (%) | ||||

| Liver | 8 (20) | 1 (12.5) | ||

| Lung | 23 (57.5) | 2 (25) | ||

| Distant lymph nodes | 6 (15) | 1 (12.5) | ||

| Bone | 4 (10) | - | ||

| Brain | 1 (2.5) | - | ||

| Ovary | 1 (2.5) | - | ||

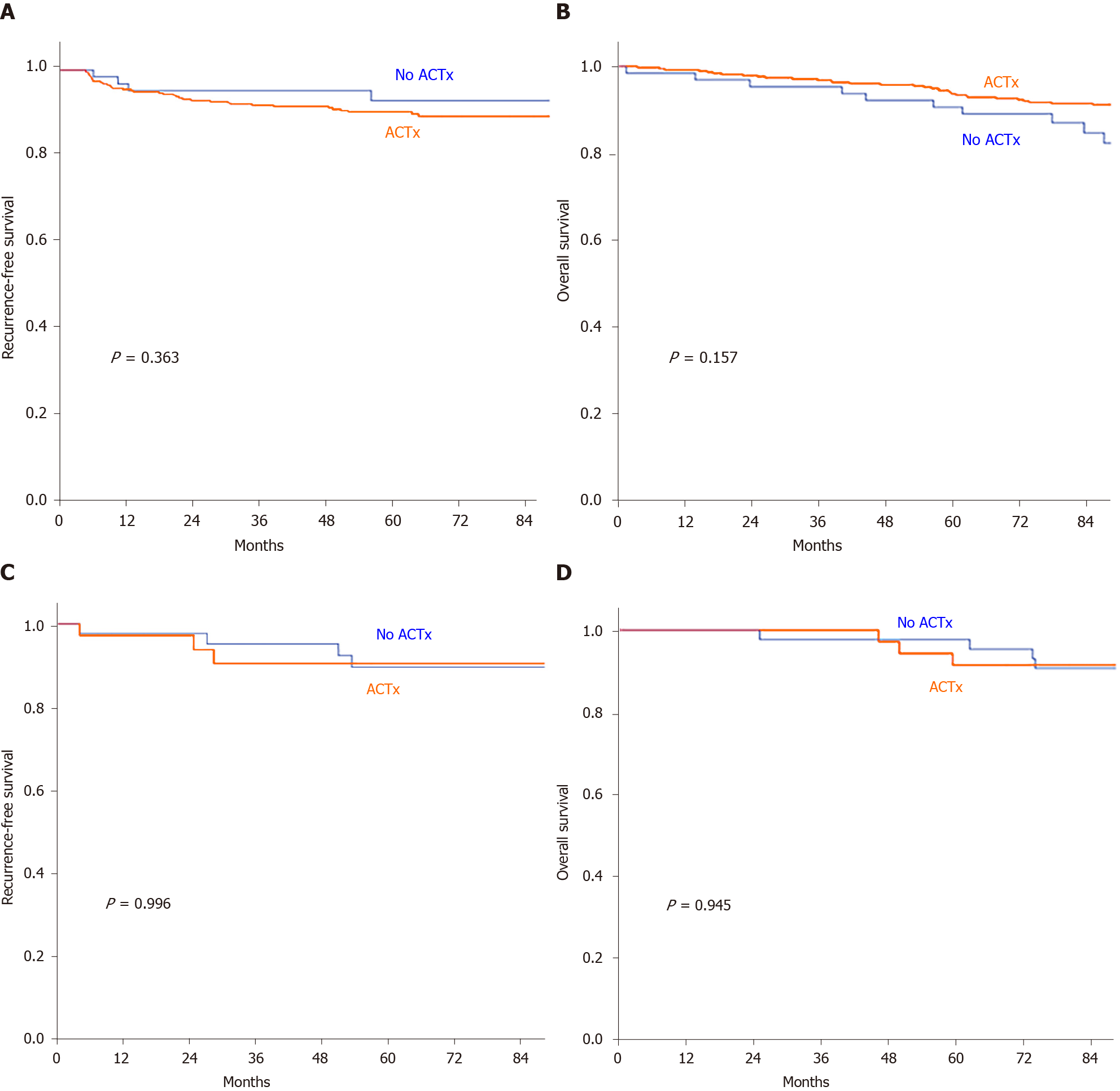

When the RFS and OS were analyzed by the type of surgery (radical resection or LE) according to the status of ACTx, no significant difference was observed with regard to the 5-year RFS in patients who underwent radical resection and LE between the ACTx group and the no ACTx group (radical resection: 90.3% vs 92.9%, P = 0.363; LE: 90.4% vs 89.6%, P = 0.996). Similarly, no significant difference was found regarding the 5-year OS in patients who underwent radical resection and LE between the ACTx group and the no ACTx group (radical resection: 93.7% vs 90.6%, P = 0.167; LE: 91.4% vs 90.7%, P = 0.945; Figure 3).

In the univariate analysis, none of the risk factors were associated with RFS, including the administration of ACTx. In the multivariate analysis, cT3–4 stage was the only risk factor associated with RFS [hazard ratio (HR): 2.57; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.07–6.16, P = 0.04]. Even in the subgroup analysis of patients with cT3–4 stage disease, ACTx was not associated with RFS (HR: 1.358, P = 0.521; Table 3). Apart from age, none of the risk factors were associated with OS in the univariate analysis. In contrast, cT stage was a significant risk factor for OS in the multivariate analysis (HR: 2.268, 95%CI: 1.09–4.74, P = 0.03). However, in the multivariate Cox regression analysis of the cT3–4 group, administration of ACTx was not a significant risk factor for OS (Table 4).

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

| HR | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | ||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 0.459 | 0.608 | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 1.331 | 1.226 | 0.563–2.671 | |||

| Sex | 0.582 | |||||

| Male | 1 | |||||

| Female | 1.77 | 0 | ||||

| cT category | 0.082 | 0.035 | ||||

| cT1–2 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| cT3–4 | 2.031 | 2.565 | 1.06–6.156 | |||

| cN category | 0.399 | |||||

| cN− | 1 | |||||

| cN+ | 0.756 | |||||

| Type of surgery | 0.927 | |||||

| Local excision | 1 | |||||

| Radical resection | 1.038 | |||||

| ypT stage | 0.389 | |||||

| ypT0 | 1 | |||||

| ypTis–1 | 0.757 | |||||

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

| HR | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | ||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 0.306 | 0.484 | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 0.729 | 0.797 | 0.422–1.504 | |||

| Age | 1.047 | 0.001 | 1.052 | 1.022–1.084 | 0.001 | |

| Sex | 0.156 | 0.213 | ||||

| Male | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Female | 0.668 | 0.701 | 0.400–1.227 | |||

| cT category | 0.122 | 0.029 | ||||

| cT1–2 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| cT3–4 | 1.757 | 2.268 | 1.085–4.741 | |||

| cN category | 0.475 | |||||

| cN− | 1 | |||||

| cN+ | 1.296 | |||||

| Type of surgery | 0.692 | |||||

| Local excision | 1 | |||||

| Radical resection | 1.174 | |||||

| ypT stage | 0.612 | |||||

| ypT0 | 1 | |||||

| ypTis–1 | 0.861 | |||||

In patients undergoing radical surgical resection, ypN stage was a risk factor associated with RFS and OS. ypN+ stage was a risk factor for RFS in both the univariate and multivariate analyses (HR: 4.86, P < 0.00 and HR: 4.74, 95%CI: 2.39–9.42, P < 0.00, respectively). It was also confirmed as a risk factor for OS in the multivariate analysis (HR: 4.33, 95%CI: 2.20–8.53, P < 0.00). However, administration of ACTx was not associated with both RFS and OS in patients who underwent radical resection.

In this study, it was found that the ACTx did not improve the RFS and OS of patients with ypT0–1 rectal cancer who underwent PCRT and resection. In the subgroup analysis according to the type of resection, administration of ACTx was not associated with RFS and OS in patients who underwent LE and those who underwent radical resection. The significant risk factors for RFS and OS were cT stage and ypN stage in patients who underwent radical resection.

The present study included patients who underwent LE and those who underwent radical resection, while previous studies included patients who underwent either radical surgical resection or TME[14-18]. Tumor regression after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy has made it possible to perform LE according to the principles of TME for rectal cancer. The rate of LE after PCRT for rectal cancer has gradually increased over time[19]. Therefore, enrollment of patients who underwent LE after PCRT in this study may have a more practical importance in the clinical decision making, especially in patients with pathological downstaging. Furthermore, patients in this study had good adherence to ACTx; hence, the efficacy of ACTx was evaluated more precisely.

Previous studies have demonstrated that patients who achieve a pathological complete response after chemoradiation have a better prognosis than those who do not achieve a pathological complete response[20-22]. However, there was a lack of consen

Recent studies based on the National Cancer Database have shown contradictory results. One study showed that ACTx was associated with improved OS in patients who achieved a pathological complete response, and while another showed that ACTx was more beneficial in patients with pretreatment node-positive cancer than those without metastatic nodes[14,15]. Although these studies analyzed a large sample of patients, limited data on patient characteristics and clinical outcomes such as local recurrence and cancer-related death could obscure the results as an unmeasured confounding factor, worsened with the statistical features of propensity score matching[34]. Another large-scale study showed an association between the administration of ACTx and lower risk of death[35]; however, this study included all patients with stage II–III disease without analyzing the benefit of ACTx in each subgroup according to the ypT stage. A previous study showed additional benefit of ACTx; however, there was possible selection bias since younger and healthier patients were more likely to receive ACTx than older adults with comorbidities[16].

Hence, the results of the current study should be carefully interpreted as the analysis was performed in patients with ypN0 and ypN+ status. Although the LN status is one of the most important prognostic factors[36,37], we could not analyze the extent of nodal involvement as LN evaluation was limited during LE. In our study, the proportion of patients with ypT0–1N+ stage in the radical resection subgroup was 7.4% (33/442), which was similar to that reported in the previous study[36]; most of the patients with ypT0–1N+ stage received ACTx (93.9%, 31/33). Therefore, the influence of ACTx in patients with ypT0–1N+ could not be sufficiently evaluated in this study. Although the accuracy of the imaging diagnosis of LN metastasis is limited in current clinical practice, the rate of LE in rectal cancer patients who achieve complete or near complete regression of the primary tumor after PCRT has increased gradually[19]. Therefore, future studies should include not only patients who have undergone LE, but also those who have undergone radical resection considering the current clinical practice. In our study, among patients who had LE, 55.1% (43/78) did not receive ACTx, and the benefit of ACTx in ypT0–1 rectal cancer patients who underwent LE could be sufficiently evaluated.

The most common ACTx regimen administered in our study was 5-FU/Leucovorin or capecitabine. Long-term results of recent studies comparing the outcome of ACTx using different agents showed that patients with ypN1b and ypN2 disease benefited from FOLFOX rather than FL[8]. Patients enrolled in our study with early ypT stage who showed good response to PCRT seemed to have a lesser oncological benefit than those included in the abovementioned trial. LN metastasis remained a risk factor for RFS and OS even in patients with ypT0–1 disease. Therefore, further studies are needed to determine whether the same conclusion can be established when a more intense chemotherapy regimen is used.

This study has some limitations, which include the retrospective review of data from a single center and the small sample size. Selection bias resulted from the inclusion of patients who either underwent radical resection or LE. As current guidelines recommend ACTx to patients after PCRT and surgical resection regardless of post-treatment stage, few patients with ypT0–1N+ disease did not receive ACTx; hence, the comparison of patients with ypN+ disease who underwent radical resection between the ACTx group and the no ACTx group may not be sufficient. These limitations may influence the reliability of the results, which should be interpreted carefully.

Despite the study limitations, we demonstrated that there was no long-term survival benefit of ACTx in patients with ypT0–1 disease after PCRT regardless of the radicality of the surgery. Hence, the necessity of ACTx in patients with cT stage disease, a risk factor associated with RFS and OS, should be carefully reviewed in future studies.

In conclusion, ACTx in patients with ypT0–1 disease who had a good response to PCRT followed by surgical resection may not be beneficial in improving the oncological outcome. Routine ACTx based on the pretreatment clinical stage should be carefully applied in the clinical setting considering the heterogenous oncological outcomes of patients at post-surgical stage.

In rectal cancer patients after preoperative chemoradiotherapy (PCRT), adjuvant chemotherapy (ACTx) is recommended regardless of post-surgical stage.

It is controversial that ACTx improves the oncologic outcome in patients in the early yp stage expected to have a good prognosis.

This study is a retrospective study that aims to evaluate the survival benefit of ACTx in patients with ypT0–1 who underwent PCRT and surgical resection, including local excision.

After identification of patients who received PCRT followed by surgical resection, analysis of the 5-yr recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) of patients with ypT0–1 rectal cancer was performed according to the status of ACTx.

There was no significant difference in the 5-year RFS and 5-year OS between the two groups. In the multivariate analysis, cT stage was associated with RFS and OS. Also, ypN stage only analyzed in the radical resection group was associated with RFS and OS.

Our study demonstrated no oncologic benefit of ACTx in patients with ypT0–1 rectal cancer after PCRT and surgical treatment regardless of the radicality of resection.

In rectal cancer treated with PCRT, ACTx use, regardless of the final pathologic stage, needs to be carefully reconsidered. For ypT0-1 rectal cancer, ACTx did not show any oncologic benefit. Therefore, risk-stratified risk-benefit consideration is important for rectal cancer patients with good pathologic results after PCRT. Further studies with prospective, large-scale, and randomized trials are needed to evaluate the efficacy of ACTx in patients with early post-treatment stage rectal cancer who have a favorable prognosis.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Macedo F S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Guo X

| 1. | NCCN. National Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines). Rectal cancer version 6. 2020. [cited 25 June 2020]. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/rectal.pdf. |

| 2. | Petersen SH, Harling H, Kirkeby LT, Wille-Jørgensen P, Mocellin S. Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy in rectal cancer operated for cure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;CD004078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kapiteijn E, Marijnen CA, Nagtegaal ID, Putter H, Steup WH, Wiggers T, Rutten HJ, Pahlman L, Glimelius B, van Krieken JH, Leer JW, van de Velde CJ; Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group. Preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for resectable rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:638-646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3104] [Cited by in RCA: 3112] [Article Influence: 129.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bosset JF, Calais G, Mineur L, Maingon P, Stojanovic-Rundic S, Bensadoun RJ, Bardet E, Beny A, Ollier JC, Bolla M, Marchal D, Van Laethem JL, Klein V, Giralt J, Clavère P, Glanzmann C, Cellier P, Collette L; EORTC Radiation Oncology Group. Fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy after preoperative chemoradiotherapy in rectal cancer: long-term results of the EORTC 22921 randomised study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:184-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 486] [Cited by in RCA: 552] [Article Influence: 50.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sauer R, Liersch T, Merkel S, Fietkau R, Hohenberger W, Hess C, Becker H, Raab HR, Villanueva MT, Witzigmann H, Wittekind C, Beissbarth T, Rödel C. Preoperative vs postoperative chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer: results of the German CAO/ARO/AIO-94 randomized phase III trial after a median follow-up of 11 years. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1926-1933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1251] [Cited by in RCA: 1480] [Article Influence: 113.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kim MJ, Jeong SY, Park JW, Ryoo SB, Cho SS, Lee KY, Park KJ. Oncologic Outcomes in Patients Who Undergo Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy and Total Mesorectal Excision for Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer: A 14-Year Experience in a Single Institution. Ann Coloproctol. 2019;35:83-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fokas E, Fietkau R, Hartmann A, Hohenberger W, Grützmann R, Ghadimi M, Liersch T, Ströbel P, Grabenbauer GG, Graeven U, Hofheinz RD, Köhne CH, Wittekind C, Sauer R, Kaufmann M, Hothorn T, Rödel C; German Rectal Cancer Study Group. Neoadjuvant rectal score as individual-level surrogate for disease-free survival in rectal cancer in the CAO/ARO/AIO-04 randomized phase III trial. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:1521-1527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hong YS, Kim SY, Lee JS, Nam BH, Kim KP, Kim JE, Park YS, Park JO, Baek JY, Kim TY, Lee KW, Ahn JB, Lim SB, Yu CS, Kim JC, Yun SH, Kim JH, Park JH, Park HC, Jung KH, Kim TW. Oxaliplatin-Based Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Rectal Cancer After Preoperative Chemoradiotherapy (ADORE): Long-Term Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:3111-3123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Benzoni E, Intersimone D, Terrosu G, Bresadola V, Cojutti A, Cerato F, Avellini C. Prognostic value of tumour regression grading and depth of neoplastic infiltration within the perirectal fat after combined neoadjuvant chemo-radiotherapy and surgery for rectal cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59:505-512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Yoo RN, Kim HJ. Organ Preservation Strategies After Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy for Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. Ann Coloproctol. 2019;35:53-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Shah R, Botteman M, Solem CT, Luo L, Doan J, Cella D, Motzer RJ. A Quality-adjusted Time Without Symptoms or Toxicity (Q-TWiST) Analysis of Nivolumab Versus Everolimus in Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma (aRCC). Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2019;17:356-365.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hisashige A, Yoshida S, Kodaira S. Cost-effectiveness of adjuvant chemotherapy with uracil-tegafur for curatively resected stage III rectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:1232-1238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Carvalho C, Glynne-Jones R. Challenges behind proving efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy after preoperative chemoradiation for rectal cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:e354-e363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Dossa F, Acuna SA, Rickles AS, Berho M, Wexner SD, Quereshy FA, Baxter NN, Chadi SA. Association Between Adjuvant Chemotherapy and Overall Survival in Patients With Rectal Cancer and Pathological Complete Response After Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy and Resection. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:930-937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Polanco PM, Mokdad AA, Zhu H, Choti MA, Huerta S. Association of Adjuvant Chemotherapy With Overall Survival in Patients With Rectal Cancer and Pathologic Complete Response Following Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy and Resection. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:938-943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Shahab D, Gabriel E, Attwood K, Ma WW, Francescutti V, Nurkin S, Boland PM. Adjuvant Chemotherapy Is Associated With Improved Overall Survival in Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer After Achievement of a Pathologic Complete Response to Chemoradiation. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2017;16:300-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gamaleldin M, Church JM, Stocchi L, Kalady M, Liska D, Gorgun E. Is routine use of adjuvant chemotherapy for rectal cancer with complete pathological response justified? Am J Surg. 2017;213:478-483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zhou J, Qiu H, Lin G, Xiao Y, Wu B, Wu W, Sun X, Lu J, Zhang G, Xu L, Liu Y. Is adjuvant chemotherapy necessary for patients with pathological complete response after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and radical surgery in locally advanced rectal cancer? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2016;31:1163-1168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | You YN, Baxter NN, Stewart A, Nelson H. Is the increasing rate of local excision for stage I rectal cancer in the United States justified? Ann Surg. 2007;245:726-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 248] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Maas M, Nelemans PJ, Valentini V, Das P, Rödel C, Kuo LJ, Calvo FA, García-Aguilar J, Glynne-Jones R, Haustermans K, Mohiuddin M, Pucciarelli S, Small W Jr, Suárez J, Theodoropoulos G, Biondo S, Beets-Tan RG, Beets GL. Long-term outcome in patients with a pathological complete response after chemoradiation for rectal cancer: a pooled analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:835-844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1189] [Cited by in RCA: 1454] [Article Influence: 96.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Capirci C, Valentini V, Cionini L, De Paoli A, Rodel C, Glynne-Jones R, Coco C, Romano M, Mantello G, Palazzi S, Mattia FO, Friso ML, Genovesi D, Vidali C, Gambacorta MA, Buffoli A, Lupattelli M, Favretto MS, La Torre G. Prognostic value of pathologic complete response after neoadjuvant therapy in locally advanced rectal cancer: long-term analysis of 566 ypCR patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72:99-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 323] [Cited by in RCA: 347] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zorcolo L, Rosman AS, Restivo A, Pisano M, Nigri GR, Fancellu A, Melis M. Complete pathologic response after combined modality treatment for rectal cancer and long-term survival: a meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:2822-2832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Breugom AJ, van Gijn W, Muller EW, Berglund Å, van den Broek CBM, Fokstuen T, Gelderblom H, Kapiteijn E, Leer JWH, Marijnen CAM, Martijn H, Meershoek-Klein Kranenbarg E, Nagtegaal ID, Påhlman L, Punt CJA, Putter H, Roodvoets AGH, Rutten HJT, Steup WH, Glimelius B, van de Velde CJH. Adjuvant chemotherapy for rectal cancer patients treated with preoperative (chemo)radiotherapy and total mesorectal excision: a Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group (DCCG) randomized phase III trial. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:696-701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 292] [Article Influence: 26.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sainato A, Cernusco Luna Nunzia V, Valentini V, De Paoli A, Maurizi ER, Lupattelli M, Aristei C, Vidali C, Conti M, Galardi A, Ponticelli P, Friso ML, Iannone T, Osti FM, Manfredi B, Coppola M, Orlandini C, Cionini L. No benefit of adjuvant Fluorouracil Leucovorin chemotherapy after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced cancer of the rectum (LARC): Long term results of a randomized trial (I-CNR-RT). Radiother Oncol. 2014;113:223-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Glynne-Jones R, Counsell N, Quirke P, Mortensen N, Maraveyas A, Meadows HM, Ledermann J, Sebag-Montefiore D. Chronicle: results of a randomised phase III trial in locally advanced rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiation randomising postoperative adjuvant capecitabine plus oxaliplatin (XELOX) vs control. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:1356-1362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lim YJ, Kim Y, Kong M. Adjuvant chemotherapy in rectal cancer patients who achieved a pathological complete response after preoperative chemoradiotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2019;9:10008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Voss RK, Lin JC, Roper MT, Al-Temimi MH, Ruan JH, Tseng WH, Tam M, Sherman MJ, Klaristenfeld DD, Tomassi MJ. Adjuvant Chemotherapy Does Not Improve Recurrence-Free Survival in Patients With Stage 2 or Stage 3 Rectal Cancer After Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy and Total Mesorectal Excision. Dis Colon Rectum. 2020;63:427-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Kim CG, Ahn JB, Shin SJ, Beom SH, Heo SJ, Park HS, Kim JH, Choe EA, Koom WS, Hur H, Min BS, Kim NK, Kim H, Kim C, Jung I, Jung M. Role of adjuvant chemotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer with ypT0-3N0 after preoperative chemoradiation therapy and surgery. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Geva R, Itzkovich E, Shamai S, Shacham-Shmueli E, Soyfer V, Klausner JM, Tulchinsky H. Is there a role for adjuvant chemotherapy in pathological complete response rectal cancer tumors following neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy? J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2014;140:1489-1494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | You KY, Huang R, Ding PR, Qiu B, Zhou GQ, Chang H, Xiao WW, Zeng ZF, Pan ZZ, Gao YH. Selective use of adjuvant chemotherapy for rectal cancer patients with ypN0. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29:529-538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Maas M, Nelemans PJ, Valentini V, Crane CH, Capirci C, Rödel C, Nash GM, Kuo LJ, Glynne-Jones R, García-Aguilar J, Suárez J, Calvo FA, Pucciarelli S, Biondo S, Theodoropoulos G, Lambregts DM, Beets-Tan RG, Beets GL. Adjuvant chemotherapy in rectal cancer: defining subgroups who may benefit after neoadjuvant chemoradiation and resection: a pooled analysis of 3,313 patients. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:212-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Gahagan JV, Whealon MD, Phelan MJ, Mills S, Jafari MD, Carmichael JC, Stamos MJ, Zell JA, Pigazzi A. Improved survival with adjuvant chemotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer patients treated with preoperative chemoradiation regardless of pathologic response. Surg Oncol. 2020;32:35-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Park IJ, Kim DY, Kim HC, Kim NK, Kim HR, Kang SB, Choi GS, Lee KY, Kim SH, Oh ST, Lim SB, Kim JC, Oh JH, Kim SY, Lee WY, Lee JB, Yu CS. Role of Adjuvant Chemotherapy in ypT0-2N0 Patients Treated with Preoperative Chemoradiation Therapy and Radical Resection for Rectal Cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;92:540-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Chang GJ. Is There Validity in Propensity Score-Matched Estimates of Adjuvant Chemotherapy Effects for Patients With Rectal Cancer? JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:921-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Turner MC, Keenan JE, Rushing CN, Gulack BC, Nussbaum DP, Benrashid E, Hyslop T, Strickler JH, Mantyh CR, Migaly J. Adjuvant Chemotherapy Improves Survival Following Resection of Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer with Pathologic Complete Response. J Gastrointest Surg. 2019;23:1614-1622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | García-Flórez LJ, Gómez-Álvarez G, Frunza AM, Barneo-Serra L, Fresno-Forcelledo MF. Response to chemoradiotherapy and lymph node involvement in locally advanced rectal cancer. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;7:196-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Lee HG, Kim SJ, Park IJ, Hong SM, Lim SB, Lee JB, Yu CS, Kim JC. Effect of Responsiveness of Lymph Nodes to Preoperative Chemoradiotherapy in Patients With Rectal Cancer on Prognosis After Radical Resection. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2019;18:e191-e199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |