Published online Aug 27, 2021. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v13.i8.871

Peer-review started: April 22, 2021

First decision: June 4, 2021

Revised: June 12, 2021

Accepted: July 9, 2021

Article in press: July 9, 2021

Published online: August 27, 2021

Processing time: 119 Days and 22.3 Hours

The effect of low ligation (LL) vs high ligation (HL) of the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) on functional outcomes during sigmoid colon and rectal cancer surgery, including urinary, sexual, and bowel function, is still controversial.

To assess the effect of LL of the IMA on genitourinary function and defecation after colorectal cancer (CRC) surgery.

EMBASE, PubMed, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library were systematically searched to retrieve studies describing sigmoid colon and rectal cancer surgery in order to compare outcomes following LL and HL. A total of 14 articles, including 4750 patients, were analyzed using Review Manager 5.3 software. Dichotomous results are expressed as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and continuous outcomes are expressed as weighted mean differences (WMDs) with 95%CIs.

LL resulted in a significantly lower incidence of nocturnal bowel movement (OR = 0.73, 95%CI: 0.55 to 0.97, P = 0.03) and anastomotic stenosis (OR = 0.31, 95%CI: 0.16 to 0.62, P = 0.0009) compared with HL. The risk of postoperative urinary dysfunction, however, did not differ significantly between the two techniques. The meta-analysis also showed no significant differences between LL and HL in terms of anastomotic leakage, postoperative complications, total lymph nodes harvested, blood loss, operation time, tumor recurrence, mortality, 5-year overall survival rate, or 5-year disease-free survival rate.

Since LL may result in better bowel function and a reduced rate of anastomotic stenosis following CRC surgeries, we suggest that LL be preferred over HL.

Core Tip: It remains unclear whether the benefits of low ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) during sigmoid colon and rectal cancer surgeries extend to improved genitourinary and defecatory function. We conducted this meta-analysis to compare low ligation and high ligation of the IMA in terms of functional outcomes, as well as other surgical and long-term survival outcomes.

- Citation: Bai X, Zhang CD, Pei JP, Dai DQ. Genitourinary function and defecation after colorectal cancer surgery with low- and high-ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery: A meta-analysis. World J Gastrointest Surg 2021; 13(8): 871-884

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v13/i8/871.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v13.i8.871

Colorectal cancer (CRC) ranks third in global cancer incidence, accounting for 10.0% of the total number of cancer cases, and ranks second in mortality[1]. Two techniques, which differ mainly in the level of inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) ligation, are used during curative surgery for cancer of the sigmoid colon and rectum. Which of high ligation (HL), which does not preserve the left colic artery, or low ligation (LL), which does preserve the left colic artery, is the better technique has been controversial since 1908[2]. Compared with LL, HL may allow a greater total number of lymph nodes to be harvested, facilitating more accurate assessment of tumor stage, and guiding adjuvant treatment. HL may be easier to achieve surgically and has been advocated by Girard et al[3]. Because HL will increase urogenital and defecation disorders, others have recently suggested that LL be preferred[4,5]. Some studies, however, showed no significance between LL and HL in terms of surgical or oncological outcomes[6,7].

Because of the ongoing controversy, previous reviews have explored the relationship between the two different approaches to IMA ligation and patient outcomes. Harjinder et al[8] found no difference between the two techniques in terms of rate of anastomotic leakage, total number of lymph nodes harvested, or survival rates. Other meta-analyses[9,10], however, found that LL of the IMA is associated with a lower risk of anastomotic leakage. At present, when completing sigmoid colon and rectal cancer surgery, it remains unclear whether the benefits of LL extend to improved genitourinary and defecatory function.

To address this, we carried out this meta-analysis to systemically compare LL and HL of the IMA in terms of functional outcomes, including urinary, sexual, and bowel function, as well as other surgical and survival outcomes.

This meta-analysis was conducted according to the guidelines for Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)[11]. The search terms “ligation” and “colorectal surgery” were used to retrieve all relevant articles from the Cochrane library, PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of Science (search last updated in December, 2020). References cited by articles identified in the initial search were used to identify additional relevant articles.

Genitourinary functional outcomes, including sexual function, urinary function, and defecation, were regarded as primary outcomes.

The secondary outcomes were total number of lymph nodes harvested, anastomotic stenosis, anastomotic leakage, postoperative complications, operation time, blood loss, mortality, recurrence, 5-year overall survival, and disease-free survival.

The following criteria were used for inclusion: (1) Studies having at least one main result; (2) Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or non-randomized studies in patients with sigmoid colon and rectal cancer; and (3) Studies comparing high and low ligation in radical resection, regardless of surgical approach. Where several reports described the same clinical study, the publication with the most complete data set was included in the meta-analysis. Articles in any language were included.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Studies having no control group; (2) Full text unavailable; and (3) Review articles, case reports, letters, or meta-analyses.

Two authors independently checked and evaluated the titles and/or abstracts of the articles and excluded any that were obviously irrelevant. The suitability of the remaining articles for inclusion in the analysis was assessed by inspection of the full article. Relevant details on research design, baseline characteristics, and outcomes were then collected. Differences in opinion between the two authors were resolved through discussion. The following data were retrieved from each article: Year of publication, first author’s name, country where the study was conducted, and the number of patients, together with age and gender. If available, supplementary information was obtained for each article included in the study.

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale[12], based on comparability between groups, quality of patient selection, patient results, and determination of exposure, was used to evaluate the quality of non-randomized studies. The Cochrane Collaborative Bias Risk Tool was used to evaluate the quality of RCTs. Research areas covered allocation concealment, selective reporting of results, sequence generation, incomplete results, blinding, and other sources of bias. The bias risk of each study was sorted as high, ambiguous, or low. Differences were settled through consensus discussions.

Statistical analyses were performed using Review Manager 5.3 software (The Cochrane Collaboration; Copenhagen, Denmark). Continuous outcomes are expressed as weigh

Our initial search identified 458 studies. After removal of duplicates and assessment of eligibility for inclusion, 14 clinical trials, which included an LL treatment group and an HL treatment group, were included in the final analysis (Figure 1). These studies involved a total of 4750 patients, with 1984 patients in the LL group and 2766 patients in the HL group. The baseline characteristics of the 14 eligible studies[4,5,7,13-23] are shown in Table 1. Quality assessments of the included studies are shown in Table 2 and Figure 2, and all endpoints are listed in Table 3.

| Ref. | Year | Country | Design | Surgical treatment (No. patients) | Male (%) LL/HL | Age, yr1 | Diagnosis | Stage (No. patients) LL/HL | |||||

| LL | HL | LL | HL | Ⅰ | Ⅱ | Ⅲ | Ⅳ | ||||||

| AlSuhaimi et al[15] | 2019 | South Korea | Retrospective cohort | 378 | 835 | 63.8/66.2 | 60.2 ± 11.5 | 60.6 ± 10.8 | Rectal cancer | NA | |||

| Chen et al[4] | 2020 | China | Retrospective cohort | 227 | 235 | 51.5/54.0 | 58.6 ± 8.9 | 57.9 ± 9.1 | Rectal cancer | 19/24 | 111/95 | 97/116 | |

| Dimitri et al[18] | 2018 | Greece | Retrospective cohort | 44 | 76 | 68.2/51.3 | 72 (64-77.8) | 70 (63-79) | Rectosigmoid and rectal cancer | 9/17 | 16/27 | 14/26 | |

| Fiori et al[5] | 2020 | Italy | RCT | 24 | 22 | 58.3/54.4 | 68 ± 11 | 68 ± 9 | Rectal cancer | 24/22 | |||

| Fujii et al[7] | 2019 | Japan | RCT | 108 | 107 | 63.0/63.6 | 66 (35-88) | 66 (30-86) | Rectal cancer | 43/45 | 20/20 | 36/36 | 4/3 |

| Kverneng Hultberg et al[20] | 2017 | England | Retrospective cohort | 432 | 373 | 52.5/63.0 | NA | Rectal cancer | 118/86 | 138/128 | 137/122 | 25/24 | |

| Lee et al[17] | 2018 | South Korea | Retrospective cohort | 83 | 51 | 71.1/66.7 | 66.6 ± 10.7 | 66.1 ± 11.5 | Sigmoid colon cancer | NA | |||

| Matsuda et al[23] | 2015 | Japan | RCT | 49 | 51 | 69.4/64.7 | 67 (45-89) | 69 (45-85) | Rectal cancer | 17/7 | 17/15 | 13/23 | 2/4 |

| Park et al[14] | 2020 | South Korea | Retrospective cohort | 163 | 613 | 65.0/66.4 | 62 (31-88) | 62 (30-86) | Distal sigmoid colon and rectal cancer | 51/175 | 35/146 | 52/229 | 10/30 |

| Wang et al[22] | 2015 | China | RCT | 65 | 63 | 64.6/60.3 | 58.6 ± 13.7 | 56.8 ± 14.2 | Rectal cancer | NA | |||

| Yasuda et al[21] | 2016 | Japan | Retrospective cohort | 147 | 42 | 62.6/61.9 | 68 ± 9.1 | 64.5 ± 9.6 | Sigmoid colon and rectal cancer | 38/2 | 44/21 | 65/19 | |

| You et al[13] | 2020 | China | Retrospective cohort | 148 | 174 | 66.2/67.2 | 58.1 ± 10.8 | 57.2 ± 10.5 | Rectal cancer | 28/38 | 59/77 | 59/58 | |

| You et al[19] | 2017 | China | Retrospective cohort | 64 | 72 | 56.3/58.3 | 60.1 ± 10.8 | 58.1 ± 10.9 | Rectal cancer | 14/16 | 20/22 | 29/23 | |

| Zhou et al[16] | 2018 | China | RCT | 52 | 52 | 61.5/59.6 | 53.9 ± 13.5 | 52.7 ± 12.9 | Rectal cancer | 4/2 | 23/27 | 25/23 | |

| Endpoint | No. of patients | No. of studies | LL | HL | OR WMD (95CI) | I2(%) | P value |

| Functional outcomes | |||||||

| Urinary dysfunction | 2029 | 7 | 1093 | 936 | OR, 1.23 (0.95-1.59) | 25 | 0.12 |

| Urinary retention | 1050 | 4 | 301 | 749 | OR, 1.51 (0.85-2.68) | 0 | 0.16 |

| Urinary infection | 1617 | 3 | 633 | 984 | OR, 0.29 (0.16-0.54) | 0 | < 0.0001 |

| Genitourinary dysfunction | 458 | 2 | 212 | 246 | OR, 0.32 (0.17-0.61) | 0 | 0.0006 |

| Nocturnal bowel movement | 884 | 3 | 461 | 423 | OR, 0.73 (0.55-0,97) | 0 | 0.03 |

| Need for antidiarrheal or laxative drugs | 187 | 2 | 94 | 93 | OR, 0.70 (0.37-1.30) | 14 | 0.26 |

| Wexner’s incontinence score | 274 | 3 | 138 | 136 | MD, -0.01 (-0.71-0.70) | 76 | 0.99 |

| Safety outcomes | |||||||

| Anastomotic leakage | 4574 | 13 | 1830 | 2744 | OR, 0.69 (0.45-1.07) | 50 | 0.10 |

| Anastomotic stenosis | 686 | 4 | 326 | 360 | OR, 0.31 (0.16-0.62) | 46 | 0.0009 |

| Postoperative complication | 2622 | 5 | 892 | 1730 | OR, 1.07 (0.66-1.72) | 62 | 0.79 |

| Mortality | 822 | 6 | 394 | 428 | OR, 2.70 (0.64-11.40) | 0 | 0.18 |

| Operative time | 2491 | 7 | 996 | 1495 | MD, 4.42 (-2.05-10.89 | 80 | 0.18 |

| Blood loss | 2357 | 6 | 913 | 1444 | MD, -0.63 (-4.01-2.76) | 76 | 0.72 |

| Oncological outcomes | |||||||

| Total lymph nodes harvested | 2491 | 7 | 996 | 1495 | MD, 0.68 (-1.03-2.38) | 94 | 0.44 |

| Recurrence | 1340 | 8 | 706 | 634 | OR, 0.97 (0.73-1.30) | 0 | 0.85 |

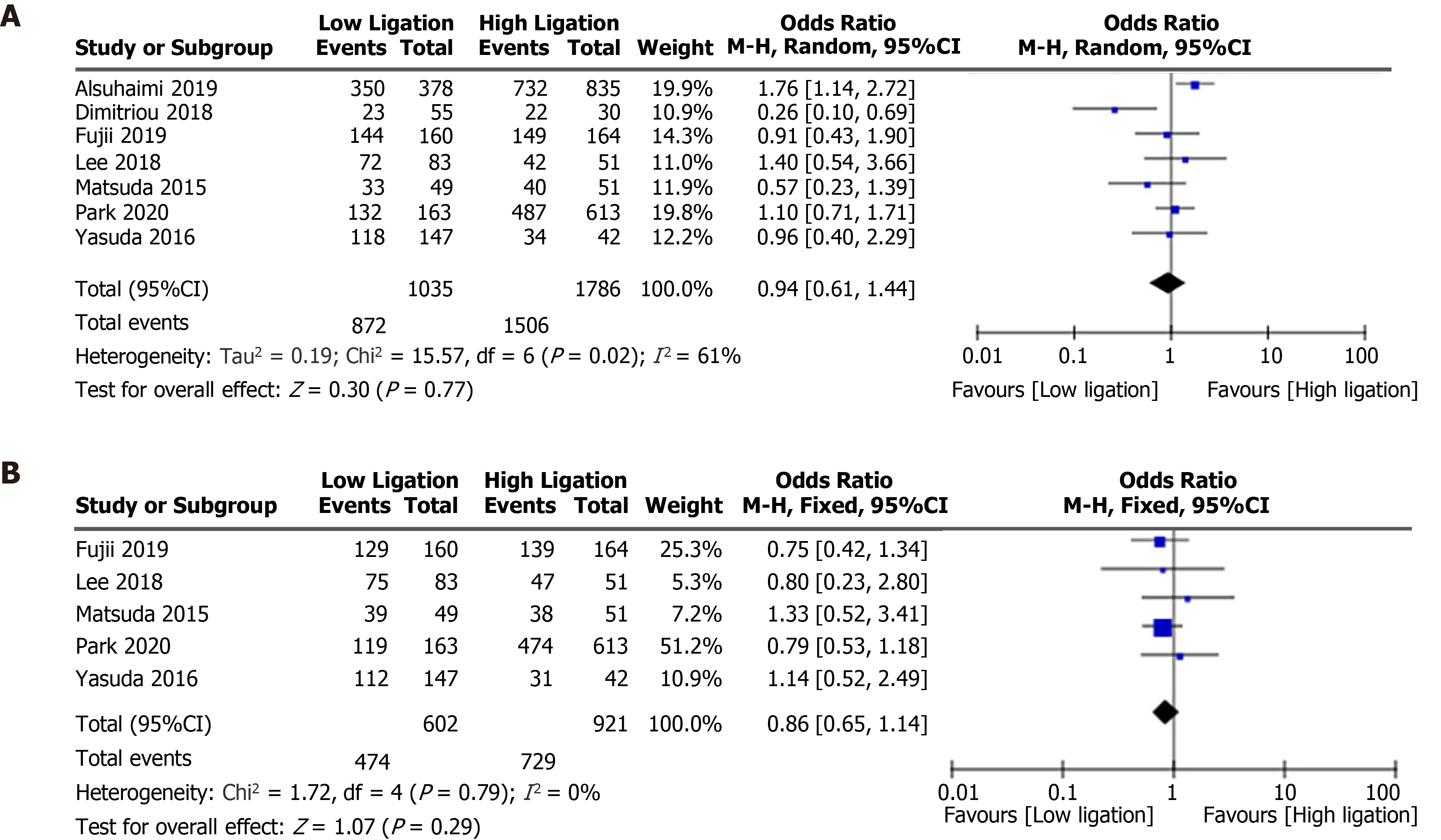

| 5-year overall survival | 2821 | 7 | 1035 | 1786 | OR, 0.94 (0.61-1.44) | 61 | 0.77 |

| 5-year disease-free survival | 1523 | 5 | 602 | 921 | OR, 0.86 (0.65-1.14) | 0 | 0.29 |

No significant differences in urinary dysfunction (OR = 1.23, 95%CI: 0.95 to 1.59, P = 0.12; Figure 3A)[4,7,16-18,20,21] or urinary retention (OR = 1.51, 95%CI: 0.85 to 2.68, P = 0.16; Figure 3B)[5,14,22,23] were found between the LL and HL groups. The LL group did, however, have a lower risk of urinary infection (OR = 0.29, 95%CI: 0.16 to 0.54, P < 0.0001; 3C)[7,15,21] and a decreased risk of genitourinary dysfunction (OR = 0.32, 95%CI: 0.17 to 0.61, P = 0.0006; Figure 3D), compared with the HL group[13,19].

Nocturnal bowel movement was lower in the LL group than in the HL group (OR = 0.73, 95%CI: 0.55 to 0.97, P = 0.03; Figure 3E)[20,22,23], but there was no difference between the two groups in terms of need for antidiarrheal or laxative drugs (OR = 0.70, 95%CI: 0.37 to 1.30, P = 0.26; Figure 3F)[22,23] or Wexner’s incontinence score (WMD, −0.01, 95%CI: −0.71 to 0.70, P = 0.99; Figure 3G)[5,22,23].

Although the LL group had a lower incidence of anastomotic stenosis than the HL group (OR = 0.31, 95%CI: 0.16 to 0.62, P = 0.0009; Figure 3H)[13,19,22,23], there were no significant differences in the anastomotic leakage rate (OR = 0.69, 95%CI: 0.45 to 1.07, P = 0.10; Figure 3I)[4,7,13-23], postoperative complication rate (OR = 1.07, 95%CI: 0.66 to 1.72, P = 0.79; Figure 3J)[7,14,15,18,21], or mortality (OR = 2.70, 95%CI: 0.64 to 11.40, P = 0.18; Figure 3K)[5,7,16,18,22,23] between the two groups. There were no differences in operative time (WMD, 4.42, 95%CI: −2.05 to 10.89, P = 0.18; Figure 3L)[4,13,15-19] or blood loss (WMD, −0.63, 95%CI: −4.01 to 2.76, P = 0.72; Figure 4A)[4,13,15,16,18,19] between the two groups.

There were no differences in the total number of lymph nodes harvested (WMD, 0.68, 95%CI: −1.03 to 2.38, P = 0.44; Figure 4B)[4,13,15-19], recurrence rate (OR = 0.97, 95%CI: 0.73 to 1.30, P = 0.85; Figure 5)[7,13,17-19,21-23], 5-year overall survival (OR = 0.94, 95%CI: 0.61 to 1.44, P = 0.77; Figure 6A)[7,14,15,17,18,21,23], or 5-year disease-free survival (OR = 0.86, 95%CI: 0.65 to 1.14, P = 0.29; Figure 6B)[7,14,17,21,23] between the LL and HL groups.

Radical resection is the most efficient way to surgically treat sigmoid colon and rectal cancer. However, the best ligation site of the IMA has been controversial for more than 100 years. The current controversy mainly involves the influence on lymph node dissection, anastomotic blood supply, postoperative autonomic function, and prognosis. Some safety and oncological outcomes following LL and HL have been investigated in previous reviews[8-10,24,25], all of which reported that LL decreased the incidence of anastomotic leakage, except for one meta-analysis that included only RCTs. A meta-analysis carried out by Hajibandeh et al[8] demonstrated that there was no significant difference in anastomotic leakage rate between the two ligation positions of the IMA. These earlier reviews also found no difference in terms of the number of lymph nodes harvested or the survival rate. Our meta-analysis, on the other hand, mainly evaluated functional outcomes and found that LL was associated with a lower risk of anastomotic stenosis, which was also related to anastomotic tension and anastomotic blood supply.

Urinary and sexual dysfunction after CRC surgery are inevitable problems, associated with injury to the superior hypogastric plexus[26]. Some studies[5,6] demonstrated that LL was associated with a lower risk of postoperative genitourinary dysfunction. One randomized study, however, found that LL was not superior to HL in preserving urinary function in an anterior resection and the authors believed that LL was a more complex procedure[7]. Although we found that LL was associated with a decreased risk of urinary infection, we found no difference between the two techni

Impaired bowel function is also a common complication after CRC surgery. Factors affecting bowel function are complex and include rectal compliance, anal sphincter function, and pelvic floor muscle contraction. The regulation of defecatory function is closely controlled by the sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves from the superior and inferior hypogastric plexus[26]. Although previous trials acquired the data at different months after surgery, acute peripheral nerve injury may take up to 6 mo to heal[27]. We therefore used Wexner’s incontinence score[28], nocturnal bowel movement, and the number of patients using antidiarrheals and laxatives 1 year after surgery to compare bowel function following the two ligation techniques.

Motility of the neorectum is closely associated with defecatory function and it has been suggested that long denervation of the neorectum following HL leads to impaired bowel function[29]. Less propagated contraction and more spastic micro-contraction were observed in patients with long denervation. Although other indicators related to bowel function were difficult to analyze because of the limitation of data extraction, we found that the LL may result in better bowel control.

Anastomotic stenosis, which is one factor used to evaluate the quality of life of patients who have undergone colorectal surgery, is similar to anastomotic leakage. When the diameter of the anastomosis is less than 12 mm, with or without intestinal obstruction, it is defined as an anastomotic stenosis, whose pathological basis is the hyperplasia of fibrous tissue caused by hypoxia[30]. Anastomotic leakage is also regarded as an essential cause of anastomotic stenosis[31]. Our results showed no difference in the incidence of anastomotic leakage, but LL was associated with a lower incidence of anastomotic stenosis. Although the analyses of anastomotic leakage and anastomotic stenosis included 13 studies and 4 studies, respectively, they did not have high heterogeneity.

From an oncological perspective, some surgeons believe that HL during radical resection of sigmoid CRC can allow removal of more lymph nodes and improve the prognosis of patients. Others, however, believe that metastasis of apical lymph nodes is rare, and that the survival rate following LL is not inferior to that following HL. There was little difference in total recurrence rate, number of lymph nodes harvested, 5-year overall survival, or 5-year disease-free survival between the two levels of ligation of the IMA in our meta-analysis.

Since autonomic function could greatly affect the quality of life of patients, we compared the outcomes of two levels of ligations of the IMA on postoperative urinary, sexual, and defecatory function. This meta-analysis can provide surgeons with suggestions for the best IMA ligation technique during radical resection of sigmoid CRC. Our meta-analysis has some limitations and there are several confounding factors, such as neoadjuvant therapy, adjuvant therapy, tumor stage, operative approach, surgical technology, and preventive stoma. Functional outcomes were not completely clear because some studies did not evaluate the preoperative genitourinary and bowel function of the patients and functional outcomes were not determined at a consistent time after surgery. Both of these factors may affect the judging of functional outcomes and we hope that future studies will address these issues.

LL may result in better bowel function and reduce the rate of anastomotic stenosis. The risk of urinary dysfunction and anastomotic leakage, however, seems to be equivalent between the two IMA ligation techniques. Since LL is less invasive and does not increase operative time, we recommend LL of the IMA in sigmoid colon and rectal cancer surgery. Future studies are needed to confirm our conclusions.

Whether the benefits of low ligation (LL) of the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) during colorectal cancer (CRC) surgeries extend to improved genitourinary and defecatory function is still controversial.

Previous studies have demonstrated that LL was associated with a lower risk of postoperative genitourinary and defecatory dysfunction in patients with CRC. One randomized study, however, found that LL was not superior to high ligation (HL) in preserving urinary function. Therefore, we carried out a meta-analysis to systemically compare functional outcomes of patients with CRC between LL and HL of the IMA.

To evaluate the effect of LL of the IMA on genitourinary function and defecation for patients after CRC surgeries.

The meta-analysis methods were adopted to realize the objectives. And statistical analyses were performed using Review Manager 5.3 software.

LL resulted in a significantly lower incidence of nocturnal bowel movement (OR = 0.73, 95%CI: 0.55 to 0.97, P = 0.03) and anastomotic stenosis (OR = 0.31, 95%CI: 0.16 to 0.62, P = 0.0009) compared with HL. The risk of postoperative urinary dysfunction, however, did not differ significantly between the two techniques. The meta-analysis also showed no significant differences between LL and HL in terms of anastomotic leakage, postoperative complications, total lymph nodes harvested, blood loss, operation time, tumor recurrence, mortality, 5-year overall survival rate, or 5-year disease-free survival rate.

Since LL may result in better bowel function and a reduced rate of anastomotic stenosis following CRC surgeries, we suggest that LL be preferred over HL.

Some limitations in this meta-analysis should be addressed carefully. First, since both randomized controlled trials and non-randomized studies were included, the randomization in the original research was limited. Second, several studies did not evaluate the preoperative genitourinary and bowel function of the patients and functional outcomes were not determined at a consistent time after surgery. In addition, there were differences in the neoadjuvant therapy, adjuvant therapy, surgical approach, and preventive stoma in this analysis. All of these factors may affect the results. Future studies are needed to address these issues.

We thank all the previous study authors whose work is included in this meta-analysis.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited Manuscript

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Sun C S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 62709] [Article Influence: 15677.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (172)] |

| 2. | Miles WE. A method of performing abdomino-perineal excision for carcinoma of the rectum and of the terminal portion of the pelvic colon (1908). CA Cancer J Clin. 1971;21:361-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Girard E, Trilling B, Rabattu PY, Sage PY, Taton N, Robert Y, Chaffanjon P, Faucheron JL. Level of inferior mesenteric artery ligation in low rectal cancer surgery: high tie preferred over low tie. Tech Coloproctol. 2019;23:267-271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chen JN, Liu Z, Wang ZJ, Zhao FQ, Wei FZ, Mei SW, Shen HY, Li J, Pei W, Wang Z, Yu J, Liu Q. Low ligation has a lower anastomotic leakage rate after rectal cancer surgery. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2020;12:632-641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fiori E, Crocetti D, Lamazza A, DE Felice F, Sterpetti AV, Irace L, Mingoli A, Sapienza P, DE Toma G. Is Low Inferior Mesenteric Artery Ligation Worthwhile to Prevent Urinary and Sexual Dysfunction After Total Mesorectal Excision for Rectal Cancer? Anticancer Res. 2020;40:4223-4228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mari GM, Crippa J, Cocozza E, Berselli M, Livraghi L, Carzaniga P, Valenti F, Roscio F, Ferrari G, Mazzola M, Magistro C, Origi M, Forgione A, Zuliani W, Scandroglio I, Pugliese R, Costanzi ATM, Maggioni D. Low Ligation of Inferior Mesenteric Artery in Laparoscopic Anterior Resection for Rectal Cancer Reduces Genitourinary Dysfunction: Results From a Randomized Controlled Trial (HIGHLOW Trial). Ann Surg. 2019;269:1018-1024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fujii S, Ishibe A, Ota M, Suwa H, Watanabe J, Kunisaki C, Endo I. Short-term and long-term results of a randomized study comparing high tie and low tie inferior mesenteric artery ligation in laparoscopic rectal anterior resection: subanalysis of the HTLT (High tie vs. low tie) study. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:1100-1110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hajibandeh S, Hajibandeh S, Maw A. Meta-analysis and Trial Sequential Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials Comparing High and Low Ligation of the Inferior Mesenteric Artery in Rectal Cancer Surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2020;63:988-999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zeng J, Su G. High ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery during sigmoid colon and rectal cancer surgery increases the risk of anastomotic leakage: a meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2018;16:157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Si MB, Yan PJ, Du ZY, Li LY, Tian HW, Jiang WJ, Jing WT, Yang J, Han CW, Shi XE, Yang KH, Guo TK. Lymph node yield, survival benefit, and safety of high and low ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery in colorectal cancer surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2019;34:947-962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, McKenzie JE. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4127] [Cited by in RCA: 4410] [Article Influence: 1102.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8858] [Cited by in RCA: 12372] [Article Influence: 824.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | You X, Liu Q, Wu J, Wang Y, Huang C, Cao G, Dai J, Chen D, Zhou Y. High vs low ligation of inferior mesenteric artery during laparoscopic radical resection of rectal cancer: A retrospective cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e19437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Park SS, Park B, Park EY, Park SC, Kim MJ, Sohn DK, Oh JH. Outcomes of high vs low ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery with lymph node dissection for distal sigmoid colon or rectal cancer. Surg Today. 2020;50:560-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | AlSuhaimi MA, Yang SY, Kang JH, AlSabilah JF, Hur H, Kim NK. Operative safety and oncologic outcomes in rectal cancer based on the level of inferior mesenteric artery ligation: a stratified analysis of a large Korean cohort. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2019;97:254-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zhou J, Zhang S, Huang J, Huang P, Peng S, Lin J, Li T, Wang J, Huang M. [Accurate low ligation of inferior mesenteric artery and root lymph node dissection according to different vascular typing in laparoscopic radical resection of rectal cancer]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2018;21:46-52. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Lee KH, Kim JS, Kim JY. Feasibility and oncologic safety of low ligation of inferior mesenteric artery with D3 dissection in cT3N0M0 sigmoid colon cancer. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2018;94:209-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Dimitriou N, Felekouras E, Karavokyros I, Pikoulis E, Vergadis C, Nonni A, Griniatsos J. High vs low ligation of inferior mesenteric vessels in rectal cancer surgery: A retrospective cohort study. J BUON. 2018;23:1350-1361. [PubMed] |

| 19. | You X, Wang Y, Chen Z, Li W, Xu N, Liu G, Zhao X, Huang C. [Clinical study of preserving left colic artery during laparoscopic total mesorectal excision for the treatment of rectal cancer]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2017;20:1162-1167. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Kverneng Hultberg D, Afshar AA, Rutegård J, Lange M, Haapamäki MM, Matthiessen P, Rutegård M. Level of vascular tie and its effect on functional outcome 2 years after anterior resection for rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2017;19:987-995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yasuda K, Kawai K, Ishihara S, Murono K, Otani K, Nishikawa T, Tanaka T, Kiyomatsu T, Hata K, Nozawa H, Yamaguchi H, Aoki S, Mishima H, Maruyama T, Sako A, Watanabe T. Level of arterial ligation in sigmoid colon and rectal cancer surgery. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14:99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wang Q, Zhang C, Zhang H, Wang Y, Yuan Z, Di C. [Effect of ligation level of inferior mesenteric artery on postoperative defecation function in patients with rectal cancer]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2015;18:1132-1135. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Matsuda K, Hotta T, Takifuji K, Yokoyama S, Oku Y, Watanabe T, Mitani Y, Ieda J, Mizumoto Y, Yamaue H. Randomized clinical trial of defaecatory function after anterior resection for rectal cancer with high vs low ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery. Br J Surg. 2015;102:501-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Fan YC, Ning FL, Zhang CD, Dai DQ. Preservation vs non-preservation of left colic artery in sigmoid and rectal cancer surgery: A meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2018;52:269-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Cirocchi R, Trastulli S, Farinella E, Desiderio J, Vettoretto N, Parisi A, Boselli C, Noya G. High tie vs low tie of the inferior mesenteric artery in colorectal cancer: a RCT is needed. Surg Oncol. 2012;21:e111-e123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lemos N, Souza C, Marques RM, Kamergorodsky G, Schor E, Girão MJ. Laparoscopic anatomy of the autonomic nerves of the pelvis and the concept of nerve-sparing surgery by direct visualization of autonomic nerve bundles. Fertil Steril. 2015;104:e11-e12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Houdek MT, Shin AY. Management and complications of traumatic peripheral nerve injuries. Hand Clin. 2015;31:151-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Jorge JM, Wexner SD. Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:77-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2089] [Cited by in RCA: 1955] [Article Influence: 61.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 29. | Koda K, Saito N, Seike K, Shimizu K, Kosugi C, Miyazaki M. Denervation of the neorectum as a potential cause of defecatory disorder following low anterior resection for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:210-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Suchan KL, Muldner A, Manegold BC. Endoscopic treatment of postoperative colorectal anastomotic strictures. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1110-1113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Guyton KL, Hyman NH, Alverdy JC. Prevention of Perioperative Anastomotic Healing Complications: Anastomotic Stricture and Anastomotic Leak. Adv Surg. 2016;50:129-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |