Published online May 27, 2021. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v13.i5.461

Peer-review started: January 19, 2021

First decision: February 14, 2021

Revised: February 21, 2021

Accepted: April 22, 2021

Article in press: April 22, 2021

Published online: May 27, 2021

Processing time: 121 Days and 16.7 Hours

The effects of various gastrectomy procedures on the patient’s quality of life (QOL) are not well understood. Thus, this nationwide multi-institutional cross-sectional study using the Postgastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Scale-45 (PGSAS-45), a well-established questionnaire designed to clarify the severity and characteristics of the postgastrectomy syndrome, was conducted.

To compare the effects of six main gastrectomy procedures on the postoperative QOL.

Eligible questionnaires retrieved from 2368 patients who underwent either of six gastrectomy procedures [total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y reconstruction (TGRY; n = 393), proximal gastrectomy (PG; n = 193), distal gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y reconstruction (DGRY; n = 475), distal gastrectomy with Billroth-I reconstruction (DGBI; n = 909), pylorus-preserving gastrectomy (PPG; n = 313), and local resection of the stomach (LR; n = 85)] were analyzed. Among the 19 main outcome measures of PGSAS-45, the severity and characteristics of postgastrectomy syndrome were compared for the aforementioned six gastrectomy procedures using analysis of means.

TGRY and PG significantly impaired the QOL of postoperative patients. Postoperative QOL was excellent in LR (cardia and pylorus were preserved with minimal resection). In procedures removing the distal stomach, diarrhea subscale (SS) and dumping SS were less frequent in PPG than in DGBI and DGRY. However, there was no difference in the postoperative QOL between DGBI and DGRY. The most noticeable adverse effects caused by gastrectomy were meal-related distress SS, dissatisfaction at the meal, and weight loss, with significant differences among the surgical procedures.

Postoperative QOL greatly differed among six gastrectomy procedures. The severity and characteristics of postgastrectomy syndrome should be considered to select gastrectomy procedures, overcome surgical shortcomings, and enhance postoperative care.

Core Tip: For surgeons, to understand the general aspects of how the site and extent of gastrectomy affect postoperative patient’s quality of life (QOL) is important. Therefore, we investigated this concern by the nationwide multi-institutional collaborative study called Postgastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Study. The overview of the effects of the six main gastrectomy procedures on the patient’s dairy living revealed that the postoperative QOL differed greatly depending on the site and extent of gastrectomy. The severity and characteristics of postgastrectomy syndrome should be considered to select gastrectomy procedures, overcome surgical shortcomings, and enhance postoperative care.

- Citation: Nakada K, Kawashima Y, Kinami S, Fukushima R, Yabusaki H, Seshimo A, Hiki N, Koeda K, Kano M, Uenosono Y, Oshio A, Kodera Y. Comparison of effects of six main gastrectomy procedures on patients’ quality of life assessed by Postgastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Scale-45. World J Gastrointest Surg 2021; 13(5): 461-475

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v13/i5/461.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v13.i5.461

Gastrectomy is widely performed and is the most effective treatment for gastric cancer. Recent improvements in early-stage diagnosis and treatment have improved the detection, treatment, and subsequent curing of the disease[1]. However, postgastrectomy syndrome occurs frequently[2-7], and the patient’s long-term impairments are a concern. In patients with gastric cancer, procedure selection depends on its location, extent, and progression. Daily life impairment caused by gastrectomy varies with the type of surgical procedure. Therefore, function-preserving gastrectomies such as proximal gastrectomies (PG) and pylorus-preserving gastrectomies (PPG)[8-10] are performed for early gastric cancer to attenuate the postgastrectomy syndrome associated with gastrectomy by reducing the extent of resection, and local resection of the stomach (LR) in rare cases[11].

Currently, a means of assessing the effect of gastrectomy on a patients’ daily living does not exist. Therefore, it was difficult to assess the severity and characteristics of postgastrectomy syndrome. In this context, we developed the Postgastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Scale-45 (PGSAS-45)[12], which is a patient-reported outcome scale, designed to assess the effect of gastrectomy on postoperative patients’ daily living. It has been reported to be useful for assessing symptoms, living status, and quality of life (QOL) of postgastrectomy patients[13-20]. Studies have investigated the postoperative QOL among procedures performed to treat gastric cancer at a specific site. However, no study has simultaneously assessed different gastrectomy procedures used to treat gastric cancer at various sites and compared the severity and characteristics of postgastrectomy syndrome for these procedures to elucidate the broader perspective of the burden of gastrectomy. Therefore, this study aimed to compare the outcomes of the six main gastrectomy procedures with respect to the patient’s QOL using PGSAS-45 in order to clarify the severity and characteristics of postgastrectomy syndrome.

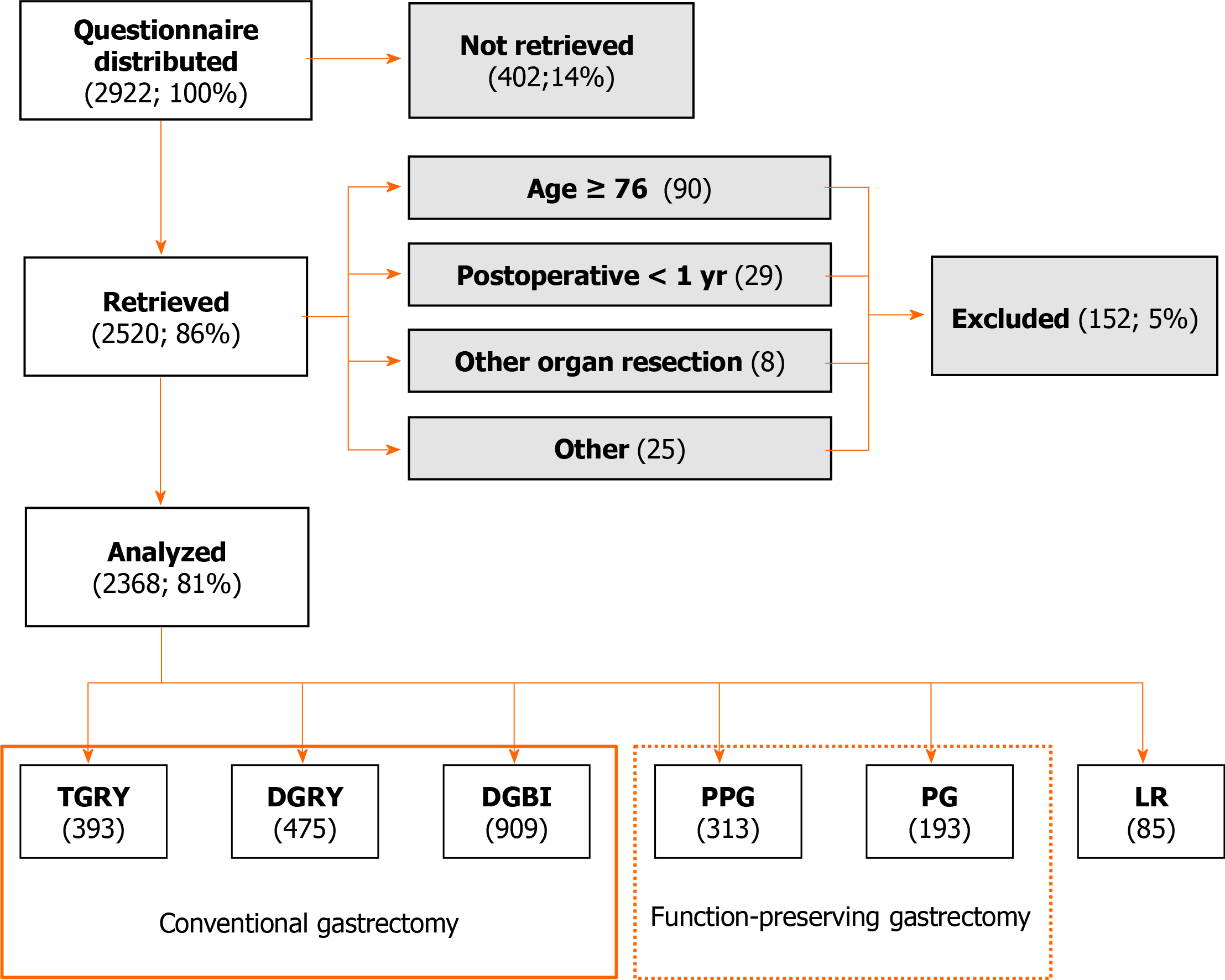

Fifty-two institutions participated in this study. The PGSAS-45 questionnaire was distributed to 2922 patients between July 2009 and December 2010. The questionnaires were given to 2922 patients, and 2520 responses were mailed to the data center. Among the 2520 respondents, 152 provided answers that were deemed unsuitable for analysis. Consequently, a total of 2368 questionnaires returned by mail were analyzed (Figure 1).

All patients enrolled in this study fulfilled the following eligibility criteria: (1) Pathologically confirmed stage IA or IB gastric cancer (for LR, other tumors, such as gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) or carcinoids, were included); (2) First-time gastrectomy; (3) Age ≥ 20 and ≤ 75 years; (4) No history of chemotherapy; (5) No recurrence or distant metastasis; (6) ≥ 1 year had elapsed since gastrectomy; (7) Performance status ≤ 1 on the Eastern Cooperative Group Scale; (8) Fully capable of understanding and responding to the questionnaire; (9) Absence of other diseases or previous surgeries that may have a greater influence on the results of the questionnaire than gastrectomy; (10) No organ failure or mental disease; and (11) Provision of written informed consent by the patient. The patients with dual malignancy or concomitant resection of other organs (co-resection equivalent to cholecystectomy being the exception) were excluded.

We performed continuous sampling from a central registration system for participant enrollment. The questionnaire was distributed to all eligible patients on presentation to the participating clinics. The patients were requested to return the completed forms to the data center by mail. The perioperative data were reported by the attending surgeon to the data center through case report forms. All QOL data from questionnaires were matched with individual patient data collected via the case report forms.

This study was approved by the local ethics committees of each participating institution and was in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and later versions. This study was registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network’s Clinical Trials Registry as trial number 000002116.

We developed the PGSAS-45 as a new integrated QOL questionnaire, comprising an 8-item short-form generic health-related QOL questionnaire (SF-8)[21] and the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS)[22,23]. In addition to the items of the SF-8 (8 items) and GSRS (15 items), 22 newly selected items are included, comprising questions on common postgastrectomy symptoms (8 items), number and type of dumping symptoms (2 items), amount and quality of dietary intake (8 items), daily activity status (1 item), and dissatisfaction with daily life (3 items). Hence, each patient was asked 45 questions in total (Table 1). The details of the PGSAS-45 have been reported previously[12].

| Domains | Subdomains | Items | Subscales | ||

| QOL | SF-8 (QOL) | 1 | Physical functioning | Five or six-point Likert scale | Physical component summary (item 1-8) |

| 2 | Role physical | Mental component summary (item 1-8) | |||

| 3 | Bodily pain | ||||

| 4 | General health | ||||

| 5 | Vitality | ||||

| 6 | Social functioning | ||||

| 7 | Role emotional | ||||

| 8 | Mental health | ||||

| Symptoms | GSRS (Symptoms) | 9 | Abdominal pains | Seven-point Likert scale | Esophageal reflux subscale (item 10, 11, 13, 24) |

| 10 | Heartburn | Except item 29 and 32 | Abdominal pain subscale (item 9, 12, 28) | ||

| 11 | Acid regurgitation | Meal-related distress subscale (item 25-27) | |||

| 12 | Sucking sensations in the epigastrium | Indigestion subscale (item 14-17) | |||

| 13 | Nausea and vomiting | Diarrhea subscale (item 19, 20, 22) | |||

| 14 | Borborygmus | Constipation subscale (item 18, 21, 23) | |||

| 15 | Abdominal distension | Dumping subscale (item 30, 31, 33) | |||

| 16 | nausea and vomiting | ||||

| 17 | Increased flatus | Total symptom scale (above seven subscales) | |||

| 18 | Decreased passage of stools | ||||

| 19 | Increased passage of stools | ||||

| 20 | Loose stools | ||||

| 21 | Hard stools | ||||

| 22 | Urgent need for defecation | ||||

| 23 | Feeling of incomplete evacuation | ||||

| PGSAS (Symptoms) | 24 | Bile regurgitation | |||

| 25 | Sense of foods sticking | ||||

| 26 | Postprandial fullness | ||||

| 27 | Early satiation | ||||

| 28 | Lower abdominal pains | ||||

| 29 | Number and type of early dumping symptoms | ||||

| 30 | Early dumping general symptoms | ||||

| 31 | Early dumping abdominal symptoms | ||||

| 32 | Number and type of late dumping symptoms | ||||

| 33 | Late dumping symptoms | ||||

| Living status | Meals (amount) 1 | 34 | Ingested amount of food per meal | - | |

| 35 | Ingested amount of food per day | ||||

| 36 | Frequency of main meals | ||||

| 37 | Frequency of additional meals | ||||

| Meals (quality) | 38 | Appetite | five-point Likert scale | Quality of ingestion subscale (item 38-40) | |

| 39 | Hunger feeling | ||||

| 40 | Satiety feeling | ||||

| Meals (amount) 2 | 41 | Necessity for additional meals | - | ||

| Social activity | 42 | Ability for working | - | ||

| QOL | Dissatisfaction (QOL) | 43 | Dissatisfaction with symptoms | Dissatisfaction for daily life subscale (item 43-45) | |

| 44 | Dissatisfaction at the meal | ||||

| 45 | Dissatisfaction at working |

Statistical analyses were performed using JMP12.0.1 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States). The differences in patient characteristics were assessed using analysis of means (ANOM) and the chi-square test, followed by residual analysis. To compare the 19 main outcome measures (MOMs) of PGSAS-45 for the six main gastrectomy techniques, the ANOM method was used, with the alpha level was set at 0.05. Values with P < 0.05 were considered significant. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Atsushi Oshio from Waseda University.

The 2368 patients who underwent the six main gastrectomy procedures were distributed according to the surgical procedure, as follows: Total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y reconstruction (TGRY), 393 patients; Proximal gastrectomy (PG), 193 patients, distal gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y reconstruction (DGRY), 475 patients; distal gastrectomy with Billroth-I reconstruction (DGBI), 909 patients; Pylorus preserving gastrectomy (PPG), 313 patients; and Local resection of the stomach (LR), 85 patients (Figure 1). The average age of the patients was 62.1 years, and for patients undergoing TGRY, the mean age was significantly higher at 63.4 years (Table 2). The overall mean postoperative period was 37.7 mo. For DGBI, the mean postoperative period was significantly longer at 40.7 mo and was significantly shorter at 31.7 mo for DGRY (Table 2). The proportion of men and women in the study population was 66% and 34%, respectively. Among the patients undergoing PPG, the proportion of women was significantly higher at 41% (Table 2). The overall mean rate for the laparoscopic approach was 38% and was significantly higher for LR (61%) and DGBI (46%), but significantly lower for PG (17%) and TGRY (25%) (Table 2). The overall mean rate of preservation of the celiac branch of the vagus nerve was 24% and was significantly higher for LR (100%), PPG (71%), and PG (44%); however, it was significantly lower for TGRY (3%), DGRY (6%), and DGBI (15%) (Table 2).

| Types of gastrectomy | TGRY (n = 393) | PG (n = 193) | DGRY (n = 475) | DGBI (n = 909) | PPG (n = 313) | LR (n = 85) | Overall (n = 2368) | P value |

| Age (yr; mean ± SD) | 63.4 ± 9.2a | 63.7 ± 7.7 | 62.0 ± 9.1 | 61.6 ± 9.1 | 61.5 ± 8.7 | 60.8 ± 9.8 | 62.1 ± 9.1 | |

| Sex: Male/female, n (Male, %) | 276/113 (71) | 139/53 (72) | 318/154 (67) | 594/311 (66) | 183/126b (59) | 48/37 (56) | 1558/794 (66) | 0.0031 |

| Postoperative period (mo; mean ± SD) | 35.0 ± 24.6 | 40.5 ± 28.1 | 31.7 ± 18.0a | 40.7 ± 30.7a | 38.4 ± 27.7 | 42.9 ± 34.2 | 37.7 ± 27.4 | |

| Approach: laparoscopic/open, n (laparoscopic, %) | 97b/293b (25) | 33b/159b (17) | 152/320 (32) | 415b/489b (46) | 136/173 (44) | 52b/33b (61) | 885/1467 (38) | < 0.00011 |

| Celiac branch of vagus saving/cut, n (saving, %) | 12b/371b (3) | 83b/105b (44) | 28b/442b (6) | 133b/754b (15) | 213b/87b (71) | 84b/0b (100) | 553/1759 (24) | < 0.00011 |

When comparing postgastrectomy symptoms of each type of gastrectomy with the overall mean symptom scores, most symptoms were severe for TGRY, while for LR, the symptoms, except for abdominal pain subscale (SS), were mild (P < 0.05). In PG, meal-related distress SS and esophageal reflux SS were serious complications (P < 0.05). The meal-related distress SS was low for both DGBI and DGRY. In addition, the esophageal reflux SS was low for DGRY and the indigestion SS was low for DGBI, respectively (P < 0.05). The diarrhea SS and dumping SS were reported less severe for PPG (P < 0.05).

Among the seven symptom SS, after gastrectomy, the most prominent symptom with higher scores were meal-related distress, constipation, and diarrhea. Additionally, as the mean score of symptoms for a specific gastrectomy type significantly differs from the overall mean score of symptoms, the symptom MOMs showing a large difference depending on the procedure were meal-related distress SS (noted in 5 of the 6 gastrectomy procedures), followed by esophageal reflux SS (4 of the 6 gastrectomy procedures) (Table 3).

| Types of gastrectomy | TGRY (n = 393) | PG (n = 193) | DGRY (n = 475) | DGBI (n = 909) | PPG (n = 313) | LR (n = 85) | Overall (n = 2368) | ||

| Domain | Main outcome measures | mean ± SD | mean ± SD | mean ± SD | mean ± SD | mean ± SD | mean ± SD | mean ± SD | N |

| Symptoms | Esophageal reflux SS | 2.0 ± 1.0b | 2.0 ± 1.0b | 1.5 ± 0.7a | 1.7 ± 0.8 | 1.7 ± 0.8 | 1.4 ± 0.5a | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 4 |

| Abdominal pain SS | 1.8 ± 0.8 | 1.7 ± 0.7 | 1.7 ± 0.8 | 1.7 ± 0.7 | 1.6 ± 0.7 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 1.7 ± 0.8 | 0 | |

| Meal-related distress SS | 2.6 ± 1.1b | 2.6 ± 1.1b | 2.1 ± 0.9a | 2.1 ± 0.9a | 2.1 ± 0.9 | 1.5 ± 0.6a | 2.2 ± 1.0 | 5 | |

| Indigestion SS | 2.3 ± 0.9b | 2.2 ± 0.8 | 2.0 ± 0.8 | 2.0 ± 0.8a | 2.0 ± 0.9 | 1.5 ± 0.6a | 2.0 ± 0.9 | 3 | |

| Diarrhea SS | 2.3 ± 1.2b | 2.0 ± 1.0 | 2.1 ± 1.1 | 2.1 ± 1.1 | 1.8 ± 1.0a | 1.5 ± 0.8a | 2.1 ± 1.1 | 3 | |

| Constipation SS | 2.1 ± 0.9 | 2.3 ± 1.1 | 2.1 ± 1.0 | 2.2 ± 1.0 | 2.2 ± 1.1 | 1.9 ± 0.9a | 2.2 ± 1.0 | 1 | |

| Dumping SS | 2.2 ± 1.1b | 2.0 ± 1.0 | 2.0 ± 1.0 | 2.0 ± 1.0 | 1.8 ± 0.9a | 1.3 ± 0.4a | 2.0 ± 1.0 | 3 | |

| Total symptom score | 2.2 ± 0.7b | 2.1 ± 0.7 | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 1.5 ± 0.4a | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 2 | |

| Living status | Change in BW | -13.8% ± 7.9%b | -10.9% ± 8.2%b | -8.4% ± 6.6% | -7.9% ± 8.1a | -6.9% ± 7.0%a | -1.6% ± 5.7%a | -8.9% ± 8.0% | 5 |

| Ingestion amount of food per meal | 6.4 ± 1.9b | 6.5 ± 1.9b | 7.2 ± 2.0 | 7.1 ± 2.0 | 7.0 ± 1.9 | 9.0 ± 1.8a | 7.0 ± 2.0 | 3 | |

| Necessity for additional meals | 2.4 ± 0.8b | 2.0 ± 0.8 | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 1.9 ± 0.8a | 1.8 ± 0.8a | 1.4 ± 0.6a | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 4 | |

| Quality of ingestion SS | 3.8 ± 1.0 | 3.6 ± 1.0b | 3.8 ± 0.9 | 3.8 ± 0.9 | 3.8 ± 0.9 | 4.0 ± 0.8a | 3.8 ± 0.9 | 2 | |

| Ability for working | 2.0 ± 0.9b | 2.0 ± 0.9 | 1.8 ± 0.9 | 1.8 ± 0.9a | 1.8 ± 0.9 | 1.4 ± 0.6a | 1.8 ± 0.9 | 3 | |

| QOL | Dissatisfaction with symptoms | 2.1 ± 1.0b | 2.0 ± 0.9 | 1.8 ± 0.9 | 1.8 ± 0.9 | 1.8 ± 0.9 | 1.2 ± 0.4a | 1.8 ± 0.9 | 2 |

| Dissatisfaction at the meal | 2.8 ± 1.1b | 2.7 ± 1.1b | 2.2 ± 1.1a | 2.2 ± 1.1a | 2.2 ± 1.1 | 1.3 ± 0.6a | 2.3 ± 1.1 | 5 | |

| Dissatisfaction at working | 2.1 ± 1.1b | 2.0 ± 1.1b | 1.7 ± 1.0 | 1.7 ± 0.9a | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 1.1 ± 0.4a | 1.8 ± 1.0 | 4 | |

| Dissatisfaction for daily life SS | 2.3 ± 0.9b | 2.2 ± 0.9b | 1.9 ± 0.9 | 1.9 ± 0.8a | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 1.2 ± 0.4a | 2.0 ± 0.9 | 4 | |

| PCS of SF-8 | 49.6 ± 5.6b | 49.5 ± 6.1 | 50.8 ± 5.6 | 50.5 ± 5.5 | 51.1 ± 5.3 | 52.4 ± 3.8a | 50.5 ± 5.6 | 2 | |

| MCS of SF-8 | 49.2 ± 6.0 | 49.0 ± 6.0 | 49.8 ± 5.7 | 49.9 ± 5.7 | 50.0 ± 6.1 | 51.6 ± 4.6a | 49.7 ± 5.8 | 1 |

Compared with the overall mean living status scores, the postgastrectomy living status for TGRY was clearly worse for all MOMs, except for the quality of ingestion SS, whereas the postgastrectomy living status for the LR was significantly better for all MOMs (P < 0.05). Moreover, for PG, the ingested amount of food per meal was low, quality of ingestion SS was poor, and weight loss was massive (P < 0.05). DGBI and PPG were associated with lesser necessity for additional meals and less weight loss; moreover, DGBI was associated with better ability for working (P < 0.05). Additionally, as the mean score of living status for a specific gastrectomy type significantly differs from the overall mean score of living status, the living status MOMs showing a large difference depending on the procedure were weight loss (noted in 5 of the 6 gastrectomy procedures), followed by necessity for additional meals (4 of the 6 gastrectomy procedures) (Table 3).

Compared with the overall mean QOL scores, TGRY showed poor scores for all QOL MOMs, except for the mental component summary of SF-8, whereas LR showed excellent scores for all QOL MOMs (P < 0.05). For PG, a significantly more patients reported dissatisfaction at the meal, dissatisfaction at working, and dissatisfaction for daily life SS (P < 0.05). The prevalence of dissatisfaction at the meal was lower for DGBI and DGRY, and that of dissatisfaction at working and dissatisfaction for daily life SS was lower for DGBI (P < 0.05). One of the QOL MOMs notable in gastrectomy was dissatisfaction at the meal. Additionally, as the mean score of QOL for a specific gastrectomy type significantly differs from the overall mean score of QOL, the QOL MOMs showing a large difference depending on the procedure, was dissatisfaction at the meal (noted in 5 of the 6 gastrectomy procedures), followed by dissatisfaction at working and dissatisfaction for daily life SS (4 of 6 gastrectomy procedures) (Table 3).

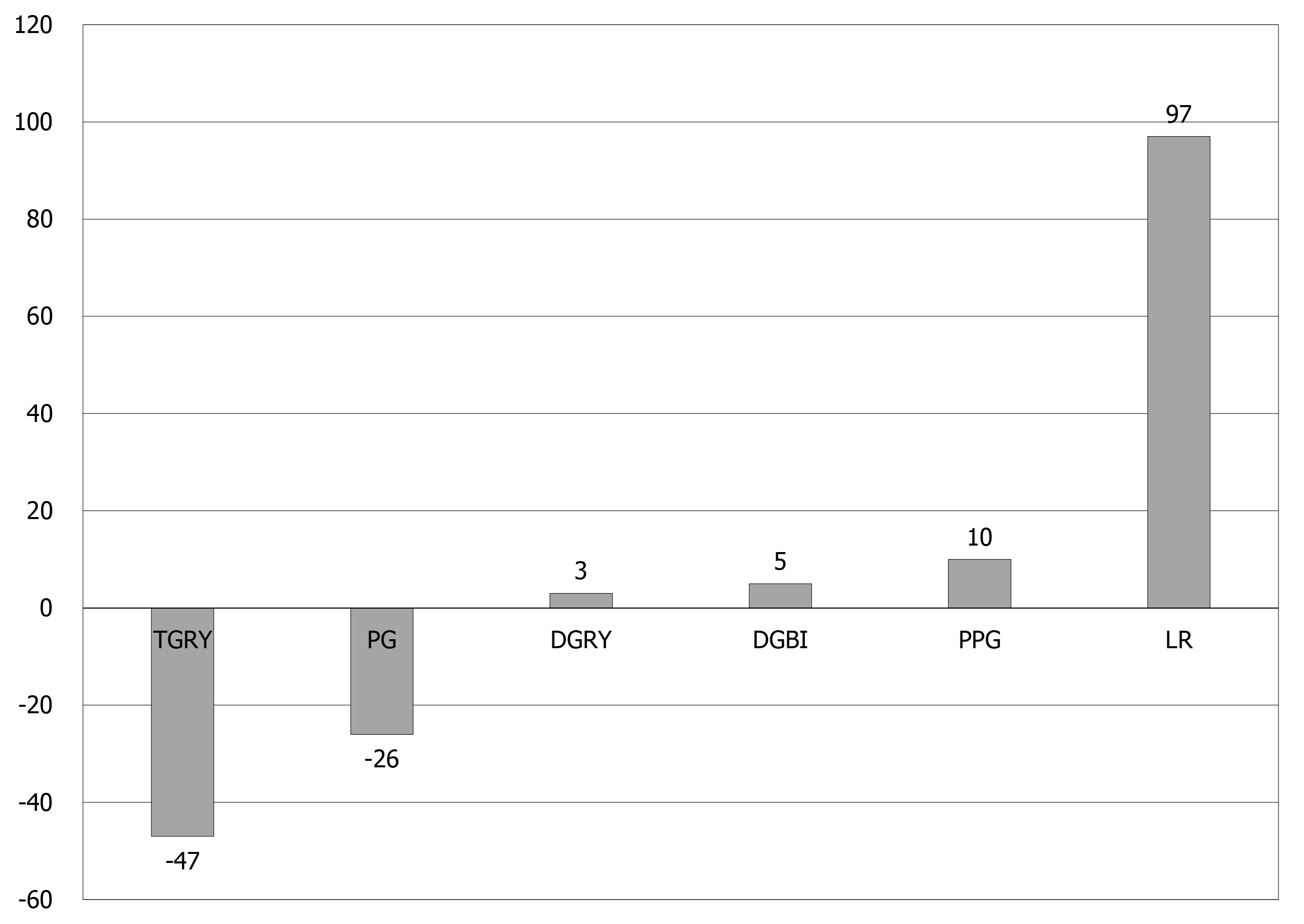

The percentage for the overall mean score of each surgical procedure was calculated for 19 MOMs of PGSAS-45 (Table 4). For every 5% deviation in score from the overall mean score, 1 point was added if the daily living condition was good and 1 point was subtracted if the daily living condition was bad. The total score of the 19 MOMs for each procedure was calculated and compared (Table 4 and Figure 2). The overall living condition of patients who underwent the aforementioned gastrectomy procedures was compared: The TGRY had a score of -47 points, which indicated a considerably worse living condition than other procedures, while LR had score of +97 points, which indicated a markedly better living condition compared to the other procedures. PG, where the proximal stomach was resected, had a score of -26 points; therefore, the QOL of patients who underwent PG was poor compared to that of patients who underwent DGRY (3 points), DGBI (5 points), and PPG (10 points), wherein the proximal stomach is presented. The QOL was better for the patients who underwent PPG where the pylorus was preserved compared to those who underwent DGBI and DGRY, and was almost similar between the patients who underwent DGBI and DGRY.

| Types of gastrectomy | TGRY | PG | DGRY | DGBI | PPG | LR | Overall | |||||||

| Domain | Main outcome measures | %a | Pointb | %a | Pointb | %a | Pointb | %a | Pointb | %a | Pointb | %a | Pointb | %a |

| Symptoms | Esophageal reflux SS | 115.5 | -3 | 116.4 | -3 | 86.6 | 2 | 99.1 | 0 | 99.1 | 0 | 79.6 | 4 | 100 |

| Abdominal pain SS | 105.0 | -1 | 99.5 | 0 | 98.9 | 0 | 100.5 | 0 | 97.7 | 0 | 87.6 | 2 | 100 | |

| Meal-related distress SS | 120.8 | -4 | 120.2 | -4 | 95.2 | 0 | 93.7 | 1 | 96.3 | 0 | 67.3 | 6 | 100 | |

| Indigestion SS | 112.0 | -2 | 105.5 | -1 | 99.8 | 0 | 97.0 | 0 | 98.0 | 0 | 72.5 | 5 | 100 | |

| Diarrhea SS | 110.4 | -2 | 94.9 | 1 | 99.9 | 0 | 102.8 | 0 | 89.3 | 2 | 73.6 | 5 | 100 | |

| Constipation SS | 96.2 | 0 | 105.9 | -1 | 97.2 | 0 | 102.2 | 0 | 103.0 | 0 | 85.6 | 2 | 100 | |

| Dumping SS | 116.3 | -3 | 103.3 | 0 | 99.5 | 0 | 99.4 | 0 | 88.6 | 2 | 64.2 | 7 | 100 | |

| Total symptom score | 111.0 | -2 | 105.8 | -1 | 97.2 | 0 | 99.4 | 0 | 95.6 | 0 | 74.4 | 5 | 100 | |

| Living status | Change in BW | 153.1 | -10 | 121.8 | -4 | 99.4 | 0 | 88.2 | 2 | 76.6 | 4 | 18.1 | 16 | 100 |

| Ingestion amount of food per meal | 91.4 | -1 | 92.2 | -1 | 102.9 | 0 | 101.3 | 0 | 99.8 | 0 | 127.6 | 5 | 100 | |

| Necessity for additional meals | 121.6 | -4 | 105.3 | -1 | 98.3 | 0 | 96.3 | 0 | 90.7 | 1 | 73.3 | 5 | 100 | |

| Quality of ingestion SS | 99.8 | 0 | 94.7 | -1 | 99.8 | 0 | 100.7 | 0 | 99.8 | 0 | 107.1 | 1 | 100 | |

| Ability for working | 112.3 | -2 | 107.5 | -1 | 100.5 | 0 | 96.2 | 0 | 97.2 | 0 | 77.4 | 4 | 100 | |

| QOL | Dissatisfaction with symptoms | 112.7 | -2 | 108.8 | -1 | 97.8 | 0 | 98.1 | 0 | 97.2 | 0 | 64.9 | 7 | 100 |

| Dissatisfaction at the meal | 122.2 | -4 | 116.6 | -3 | 94.6 | 1 | 95.0 | 1 | 96.9 | 0 | 54.7 | 9 | 100 | |

| Dissatisfaction at working | 121.1 | -4 | 115.2 | -3 | 97.2 | 0 | 94.7 | 1 | 94.2 | 1 | 62.5 | 7 | 100 | |

| Dissatisfaction for daily life SS | 118.9 | -3 | 113.6 | -2 | 96.4 | 0 | 95.9 | 0 | 96.1 | 0 | 60.2 | 7 | 100 | |

| PCS of SF-8 | 98.3 | 0 | 98.1 | 0 | 100.6 | 0 | 100.1 | 0 | 101.1 | 0 | 103.9 | 0 | 100 | |

| MCS of SF-8 | 98.8 | 0 | 98.5 | 0 | 100.2 | 0 | 100.2 | 0 | 100.5 | 0 | 103.6 | 0 | 100 | |

| QOL score (Total point) | -47 | -26 | 3 | 5 | 10 | 97 |

In this study, we developed the PGSAS-45 questionnaire for the assessment of postgastrectomy syndrome. Using this questionnaire, we examined the effects of the six main gastrectomy procedures on patients’ daily living. The results revealed that TGRY had the worst postoperative QOL score, whereas LR had the highest postoperative QOL score. For PG, where the proximal stomach is resected, the postoperative QOL was clearly worse than that for PPG, DGBI, and DGRY, where the proximal stomach is preserved. Post-PPG, where the pylorus was preserved, the QOL was slightly better than that of post-DGBI and -DGRY. No significant difference was found between DGBI and DGRY in terms of QOL. Among the 19 MOMs in PGSAS-45, the major differences in the surgical procedures were meal-related distress SS and esophageal reflux SS with respect to the symptoms, weight loss and necessity for additional meals with respect to the living status, and dissatisfaction at the meal, dissatisfaction at working, and dissatisfaction for daily life SS with respect to the QOL. After gastrectomy, the most prominent burdens were meal-related distress SS, constipation SS, diarrhea SS, and dissatisfaction at the meal. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to simultaneously examine the effects of various gastrectomy procedures on the patients’ daily living postoperatively and to clarify the overall characteristics of postgastrectomy syndrome.

In recent years, the rate of detection of early-stage gastric cancer has increased due to widespread medical screening and improvement of diagnostic techniques[1]. Advances in treatment also increase the number of patients who can attain long-term postgastrectomy survival[1]. On the contrary, various complications, called postgastrectomy syndrome, occur after gastrectomy[2-7], which become clinical problems that interfere with daily living. Within this context, there has been increasing interest in reducing the incidence of postgastrectomy syndrome and improving postoperative patients’ QOL, and the introduction of function-preserving surgery, such as PG and PPG[8-10], and minimally invasive surgery, such as laparoscopic surgery[24], has increased. These function-preserving surgical procedures are also accepted by the fourth edition of the gastric cancer treatment guidelines (2017) as an alternative treatment of early-stage gastric cancer (cT1N0M0)[25].

The primary purpose of gastrectomy is to cure cancer, and then, to allow the patient to live comfortably at the same level as their preoperative condition. To improve the QOL of postgastrectomy patients, it is important to select a gastrectomy procedure considering the patient’s postoperative QOL. However, to achieve this, a question

To date, several studies have compared various gastrectomy procedures as treatment of gastric cancer on a specific site. Total gastrectomy was often performed for upper gastric cancer, but in recent years, PG, which is a function-preserving surgery, has often been performed to treat early-stage gastric cancer for expecting better QOL[8-10]. A study comparing postoperative QOL between total gastrectomy and PG shows that the latter results in better QOL[29] with less diarrhea and dumping symptoms, less weight loss, and less necessity for additional meals[19]. On the contrary, reflux esophagitis and anastomotic stricture have been reported in PG[17,30] and remains a problem. In this study, PG had a total QOL score of -26 points compared with TGRY having -47 points. This shows that PG has lesser worse effects on QOL than TGRY, resulting in less impairment in daily living.

Distal gastrectomy is often performed for middle-third gastric cancer; however, PPG has also been selected as a function-preserving surgery for early-stage gastric cancer[8-10]. In studies comparing the postoperative QOL of distal gastrectomy and PPG, PPG was reported to have better QOL[13,14,31-33] with fewer occurrences of diarrhea and dumping, less weight loss, and less necessity for additional meals[13]. In this study, DGBI had QOL score of 5 points, and DGRY had 3 points vs PPG’s score of 10 points, indicating that PPG provides better QOL than distal gastrectomy.

Distal gastrectomy is performed as a standard surgical procedure for lower gastric cancer. DGBI and DGRY are mainly performed as reconstructive methods. Many studies have compared DGBI with DGRY[20,34-41], each of which has reported benefits, such as lesser weight loss in DGBI[20] and lower occurrence of residual gastritis and esophageal reflux symptoms in DGRY[20,38,41]. However, there is no definitive view on which of the two reconstructive surgeries is effective. In this study, DGRY (3 points) and DGBI (5 points) had virtually identical scores.

The results of this study were consistent with previous studies comparing various contrasting rival gastrectomy procedures. As mentioned above, various gastrectomy procedures were compared, which revealed an increase of evidence, showing the usefulness of function-preserving surgery. In the future, we anticipate that function-preserving gastrectomy will be applied to a wider extent to address early-stage gastric cancer.

In the overall characteristics, the worse effects of total gastrectomy on daily life were greater than those in the other five procedures (Table 4 and Figure 2) and fatal. In recent years, PG has been frequently performed for early-stage upper gastric cancer, which reduces the incidence of postgastrectomy syndrome, and the postoperative QOL is better than that in total gastrectomy. Alternatively, subtotal gastrectomy is performed, which leaves a portion of the proximal stomach even if the size of the remaining stomach becomes considerably small[42,43], and its QOL is reported better than that of TG[43]. If oncological safety is maintained, avoiding total gastrectomy as much as possible, and actively adopting a procedure that leaves either the distal stomach or a portion of the proximal stomach may help improve postoperative QOL.

In contrast, the QOL after LR was by far better than that after other gastrectomy procedures. Many reports have indicated that QOL after LR was favorable[15,44,45] and that residual stomach functions were retained[44]. Local gastric resection is often performed for GISTs; however, it has been performed as a surgical treatment for early-stage gastric cancers based on the sentinel lymph node concept[45,46]. Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) has been increasingly performed for early-stage gastric cancers, and its applicability continues to increase[47]. The QOL after ESD is especially favorable[48], and it would be an ideal treatment method if gastric cancer could be completely cured. Meanwhile, gastrectomy procedures, such as PG, PPG, and DG have been performed in conjunction with the preservation of the celiac branch of the vagus nerve as function-preserving gastrectomy for lesions in early-stage non-ESD applicable gastric cancers. However, there is still a major gap between functional preservation after gastrectomy and ESD with regards to the patients' QOL. In recent years, sentinel node navigation surgery has been incorporated against early-stage non-ESD applicable gastric cancers by safely employing LR while maintaining oncological safety. As the present results show, the QOL after LR is exceedingly favorable compared to that after PPG and PG; therefore, LR may be an effective treatment option for some early-stage non-ESD applicable gastric cancers. We anticipate the safe introduction of LR against early-stage non-ESD applicable gastric cancers with the accumulation of evidence in the future.

Among the MOMs of PGSAS-45, the major differences according to the type of procedure were meal-related distress SS, change in body weight, and dissatisfaction at the meal. Therefore, the effect of gastrectomy on meal-related MOMs was extremely large, and this was considered the most important factor contributing to the reduction of QOL of postoperative patients. Of the seven symptoms SS of PGSAS-45, meal-related distress SS and dumping SS were reported to have the largest influence on QOL, reducing postgastrectomy QOL[16]. Therefore, the procedure should be improved to reduce meal-related distress SS and dumping SS.

This study has limitations. First, since the choice of gastrectomy is mainly based on the site and spread of gastric cancer, simultaneously comparing various procedures performed on gastric cancer of different sites has only a little significance on the selection of the type of gastrectomy. However, it is important for surgeons to understand the general aspects of how the site and extent of gastrectomy affect patient’s postoperative QOL. Second, this is a retrospective study, and there is a bias in the number of cases between each surgery. However, the overall analysis was based on a large number of cases (n = 2368), and the progression was relatively early as stage IA/IB. Thus, we believe that the difference in the progression of cancer has little influence on the differences between each procedure and mainly reflects the effect of the procedures.

This study provided an overview of the severity and characteristics of postgastrectomy syndrome in patients who underwent the six main gastrectomy procedures. It also clarified that the postoperative QOL differed greatly depending on the site and extent of gastrectomy. To improve postgastrectomy QOL, it is important for surgeons to understand these matters to select the appropriate procedure, to improve the surgical technique to compensate for the shortcomings of each procedure, and to enhance postoperative care by providing appropriate dietary guidance and detecting and addressing postgastrectomy syndromes at an early stage.

No study has simultaneously assessed the effects of the different gastrectomy procedures used to treat gastric cancer at various sites on the postgastrectomy quality of life (QOL).

It is important for surgeons to understand the general aspects of how the site and extent of gastrectomy affect patient’s postoperative QOL.

The aim of this study was to compare the effects of six main gastrectomy procedures on the postoperative QOL using the Postgastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Scale-45 (PGSAS-45).

The 2368 patients who underwent either of the six main gastrectomy procedures [total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y reconstruction (TGRY; n = 393), proximal gastrectomy (PG; n = 193), distal gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y reconstruction (DGRY; n = 475), distal gastrectomy with Billroth-I reconstruction (DGBI; n = 909), pylorus-preserving gastrectomy (PPG; n = 313), and local resection of the stomach (LR; n = 85)] were enrolled in this study. The severity and characteristics of postgastrectomy syndrome were compared among the six gastrectomy procedures by the main outcome measures of PGSAS-45.

Postoperative QOL was greatly impaired in TGRY and PG, and was excellent in LR. After distal gastrectomy, diarrhea and dumping were less frequent in PPG, and there was no difference between DGBI and DGRY. The most noticeable adverse effects with significant differences among the gastrectomy procedures were meal-related distress SS, dissatisfaction at the meal, and weight loss.

Postoperative QOL greatly differed depending on the site and extent of gastrectomy.

To improve postgastrectomy QOL, it is important for surgeons to understand these matters to select the appropriate procedure, to improve the surgical technique to compensate for the shortcomings of each procedure, and to enhance postoperative care by providing appropriate dietary guidance and detecting and addressing postgastrectomy syndromes at an early stage.

This study was completed by 52 institutions in Japan. The authors thank all physicians who participated in this study and the patients whose cooperation made this study possible.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Japan Surgical Society, No. 0248522; The Japanese Society of Gastroenterological Surgery, No. G0136608; and The Japanese Society of Gastroenterology, No. 16095.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Shi Y S-Editor: Liu M L-Editor: A P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Nashimoto A, Akazawa K, Isobe Y, Miyashiro I, Katai H, Kodera Y, Tsujitani S, Seto Y, Furukawa H, Oda I, Ono H, Tanabe S, Kaminishi M. Gastric cancer treated in 2002 in Japan: 2009 annual report of the JGCA nationwide registry. Gastric Cancer. 2013;16:1-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 312] [Cited by in RCA: 372] [Article Influence: 31.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bolton JS, Conway WC 2nd. Postgastrectomy syndromes. Surg Clin North Am. 2011;91:1105-1122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Carvajal SH, Mulvihill SJ. Postgastrectomy syndromes: dumping and diarrhea. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1994;23:261-279. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Davis JL, Ripley RT. Postgastrectomy Syndromes and Nutritional Considerations Following Gastric Surgery. Surg Clin North Am. 2017;97:277-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 7. | Jay BS, Burrell M. Iatrogenic problems following gastric surgery. Gastrointest Radiol. 1977;2:239-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hiki N, Nunobe S, Kubota T, Jiang X. Function-preserving gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:2683-2692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Katai H. Function-preserving surgery for gastric cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2006;11:357-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nunobe S, Hiki N. Function-preserving surgery for gastric cancer: current status and future perspectives. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Seto Y, Yamaguchi H, Shimoyama S, Shimizu N, Aoki F, Kaminishi M. Results of local resection with regional lymphadenectomy for early gastric cancer. Am J Surg. 2001;182:498-501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nakada K, Ikeda M, Takahashi M, Kinami S, Yoshida M, Uenosono Y, Kawashima Y, Oshio A, Suzukamo Y, Terashima M, Kodera Y. Characteristics and clinical relevance of postgastrectomy syndrome assessment scale (PGSAS)-45: newly developed integrated questionnaires for assessment of living status and quality of life in postgastrectomy patients. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:147-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fujita J, Takahashi M, Urushihara T, Tanabe K, Kodera Y, Yumiba T, Matsumoto H, Takagane A, Kunisaki C, Nakada K. Assessment of postoperative quality of life following pylorus-preserving gastrectomy and Billroth-I distal gastrectomy in gastric cancer patients: results of the nationwide postgastrectomy syndrome assessment study. Gastric Cancer. 2016;19:302-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Hosoda K, Yamashita K, Sakuramoto S, Katada N, Moriya H, Mieno H, Watanabe M. Postoperative quality of life after laparoscopy-assisted pylorus-preserving gastrectomy compared with laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy: A cross-sectional postal questionnaire survey. Am J Surg. 2017;213:763-770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Isozaki H, Matsumoto S, Murakami S, Takama T, Sho T, Ishihara K, Sakai K, Takeda M, Nakada K, Fujiwara T. Diminished Gastric Resection Preserves Better Quality of Life in Patients with Early Gastric Cancer. Acta Med Okayama. 2016;70:119-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Nakada K, Takahashi M, Ikeda M, Kinami S, Yoshida M, Uenosono Y, Kawashima Y, Nakao S, Oshio A, Suzukamo Y, Terashima M, Kodera Y. Factors affecting the quality of life of patients after gastrectomy as assessed using the newly developed PGSAS-45 scale: A nationwide multi-institutional study. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:8978-8990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Nishigori T, Okabe H, Tsunoda S, Shinohara H, Obama K, Hosogi H, Hisamori S, Miyazaki K, Nakayama T, Sakai Y. Superiority of laparoscopic proximal gastrectomy with hand-sewn esophagogastrostomy over total gastrectomy in improving postoperative body weight loss and quality of life. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:3664-3672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Takahashi M, Terashima M, Kawahira H, Nagai E, Uenosono Y, Kinami S, Nagata Y, Yoshida M, Aoyagi K, Kodera Y, Nakada K. Quality of life after total vs distal gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y reconstruction: Use of the Postgastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Scale-45. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:2068-2076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Takiguchi N, Takahashi M, Ikeda M, Inagawa S, Ueda S, Nobuoka T, Ota M, Iwasaki Y, Uchida N, Kodera Y, Nakada K. Long-term quality-of-life comparison of total gastrectomy and proximal gastrectomy by postgastrectomy syndrome assessment scale (PGSAS-45): a nationwide multi-institutional study. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:407-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Terashima M, Tanabe K, Yoshida M, Kawahira H, Inada T, Okabe H, Urushihara T, Kawashima Y, Fukushima N, Nakada K. Postgastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Scale (PGSAS)-45 and changes in body weight are useful tools for evaluation of reconstruction methods following distal gastrectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21 Suppl 3:S370-S378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Turner-Bowker DM, Bayliss MS, Ware JE Jr, Kosinski M. Usefulness of the SF-8 Health Survey for comparing the impact of migraine and other conditions. Qual Life Res. 2003;12:1003-1012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 254] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Revicki DA, Wood M, Wiklund I, Crawley J. Reliability and validity of the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Qual Life Res. 1998;7:75-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 369] [Cited by in RCA: 447] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Svedlund J, Sjödin I, Dotevall G. GSRS--a clinical rating scale for gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and peptic ulcer disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:129-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 884] [Cited by in RCA: 1034] [Article Influence: 27.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hong L, Han Y, Jin Y, Zhang H, Zhao Q. The short-term outcome in esophagogastric junctional adenocarcinoma patients receiving total gastrectomy: laparoscopic vs open gastrectomy--a retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2013;11:957-961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2014 (ver. 4). Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:1-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1575] [Cited by in RCA: 1913] [Article Influence: 239.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 26. | Goh YM, Gillespie C, Couper G, Paterson-Brown S. Quality of life after total and subtotal gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma. Surgeon. 2015;13:267-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lee MS, Ahn SH, Lee JH, Park DJ, Lee HJ, Kim HH, Yang HK, Kim N, Lee WW. What is the best reconstruction method after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer? Surg Endosc. 2012;26:1539-1547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Miyoshi K, Fuchimoto S, Ohsaki T, Sakata T, Ohtsuka S, Takakura N. Long-term effects of jejunal pouch added to Roux-en-Y reconstruction after total gastrectomy. Gastric Cancer. 2001;4:156-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Namikawa T, Oki T, Kitagawa H, Okabayashi T, Kobayashi M, Hanazaki K. Impact of jejunal pouch interposition reconstruction after proximal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer on quality of life: short- and long-term consequences. Am J Surg. 2012;204:203-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 30. | Pu YW, Gong W, Wu YY, Chen Q, He TF, Xing CG. Proximal gastrectomy vs total gastrectomy for proximal gastric carcinoma. A meta-analysis on postoperative complications, 5-year survival, and recurrence rate. Saudi Med J. 2013;34:1223-1228. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Huang C, Yu F, Zhao G, Xia X. Postoperative quality of life after laparoscopy-assisted pylorus-preserving gastrectomy compared with laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35:1712-1719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Isozaki H, Okajima K, Momura E, Ichinona T, Fujii K, Izumi N, Takeda Y. Postoperative evaluation of pylorus-preserving gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 1996;83:266-269. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Xiao XM, Gaol C, Yin W, Yu WH, Qi F, Liu T. Pylorus-Preserving vs Distal Subtotal Gastrectomy for Surgical Treatment of Early Gastric Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2014;61:870-879. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Du N, Chen M, Shen Z, Li S, Chen P, Khadaroo PA, Mao D, Gu L. Comparison of Quality of Life and Nutritional Status of Between Roux-en-Y and Billroth-I Reconstruction After Distal Gastrectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutr Cancer. 2020;72:849-857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Komatsu S, Ichikawa D, Kubota T, Okamoto K, Shiozaki A, Fujiwara H, Konishi H, Morimura R, Murayama Y, Kuriu Y, Ikoma H, Nakanishi M, Sakakura C, Otsuji E. Clinical outcomes and quality of life according to types of reconstruction following laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2015;25:69-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Liu XF, Gao ZM, Wang RY, Wang PL, Li K, Gao S. Comparison of Billroth I, Billroth II, and Roux-en-Y reconstructions after distal gastrectomy according to functional recovery: a meta-analysis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2019;23:7532-7542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Nakamura M, Nakamori M, Ojima T, Iwahashi M, Horiuchi T, Kobayashi Y, Yamade N, Shimada K, Oka M, Yamaue H. Randomized clinical trial comparing long-term quality of life for Billroth I vs Roux-en-Y reconstruction after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2016;103:337-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Nunobe S, Okaro A, Sasako M, Saka M, Fukagawa T, Katai H, Sano T. Billroth 1 vs Roux-en-Y reconstructions: a quality-of-life survey at 5 years. Int J Clin Oncol. 2007;12:433-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Takiguchi S, Yamamoto K, Hirao M, Imamura H, Fujita J, Yano M, Kobayashi K, Kimura Y, Kurokawa Y, Mori M, Doki Y; Osaka University Clinical Research Group for Gastroenterological Study. A comparison of postoperative quality of life and dysfunction after Billroth I and Roux-en-Y reconstruction following distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer: results from a multi-institutional RCT. Gastric Cancer. 2012;15:198-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Toyomasu Y, Ogata K, Suzuki M, Yanoma T, Kimura A, Kogure N, Ohno T, Kamiyama Y, Mochiki E, Kuwano H. Comparison of the Physiological Effect of Billroth-I and Roux-en-Y Reconstruction Following Laparoscopic Distal Gastrectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2018;28:328-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Yang K, Zhang WH, Liu K, Chen XZ, Zhou ZG, Hu JK. Comparison of quality of life between Billroth-І and Roux-en-Y anastomosis after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer: A randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep. 2017;7:11245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 42. | Jiang X, Hiki N, Nunobe S, Nohara K, Kumagai K, Sano T, Yamaguchi T. Laparoscopy-assisted subtotal gastrectomy with very small remnant stomach: a novel surgical procedure for selected early gastric cancer in the upper stomach. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:194-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Kosuga T, Hiki N, Nunobe S, Noma H, Honda M, Tanimura S, Sano T, Yamaguchi T. Feasibility and nutritional impact of laparoscopy-assisted subtotal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer in the upper stomach. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:2028-2035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Kawamura M, Nakada K, Konishi H, Iwasaki T, Murakami K, Mitsumori N, Hanyu N, Omura N, Yanaga K. Assessment of motor function of the remnant stomach by ¹³C breath test with special reference to gastric local resection. World J Surg. 2014;38:2898-2903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Okubo K, Arigami T, Matsushita D, Sasaki K, Kijima T, Noda M, Uenosono Y, Yanagita S, Ishigami S, Maemura K, Natsugoe S. Evaluation of postoperative quality of life by PGSAS-45 following local gastrectomy based on the sentinel lymph node concept in early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2020;23:746-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Kinami S, Kosaka T. Laparoscopic sentinel node navigation surgery for early gastric cancer. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Nishizawa T, Yahagi N. Long-Term Outcomes of Using Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection to Treat Early Gastric Cancer. Gut Liver. 2018;12:119-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Liu Q, Ding L, Qiu X, Meng F. Updated evaluation of endoscopic submucosal dissection vs surgery for early gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2020;73:28-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |