Published online May 27, 2021. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v13.i5.443

Peer-review started: December 24, 2020

First decision: January 11, 2021

Revised: January 15, 2021

Accepted: April 12, 2021

Article in press: April 12, 2021

Published online: May 27, 2021

Processing time: 147 Days and 15.9 Hours

The most common causes of outlet obstructive constipation (OOC) are rectocele and internal rectal prolapse. The surgical methods for OOC are diverse and difficult, and the postoperative complications and recurrence rate are high, which results in both physical and mental pain in patients. With the continuous deepening of the surgeon’s concept of minimally invasive surgery and continuous in-depth research on the mechanism of OOC, the treatment concepts and surgical methods are continuously improved.

To determine the efficacy of the TST36 stapler in the treatment of rectocele combined with internal rectal prolapse.

From January 2017 to July 2019, 49 female patients with rectocele and internal rectal prolapse who met the inclusion criteria were selected for treatment using the TST36 stapler.

Forty-five patients were cured, 4 patients improved, and the cure rate was 92%. The postoperative obstructed defecation syndrome score, the defecation frequen

The TST36 stapler is safe and effective in treating rectocele combined with internal rectal prolapse and is worth promoting in clinical work.

Core Tip: Clinical observations were carried out in 49 female patients with rectocele and internal rectal prolapse who met the inclusion criteria and underwent surgery with the TST36 stapler. The postoperative obstructed defecation syndrome score, defecation frequency score, time/straining intensity, and sensation of incomplete evacuation were significantly lower than those before treatment. The initial and maximum defecation thresholds in patients after surgery were significantly lower than those before treatment. The patients’ postoperative ratings of rectocele, resting phase, and defecation phase were significantly decreased compared with those before treatment.

- Citation: Meng J, Yin ZT, Zhang YY, Zhang Y, Zhao X, Zhai Q, Chen DY, Yu WG, Wang L, Wang ZG. Therapeutic effects of the TST36 stapler on rectocele combined with internal rectal prolapse. World J Gastrointest Surg 2021; 13(5): 443-451

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v13/i5/443.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v13.i5.443

Constipation is divided into three categories, outlet obstructive constipation (OOC), slow transit constipation, and mixed constipation. Of these, OOC is more common[1] and seriously affects the quality of life of patients[2-4]. The most common causes of OOC are rectocele (RC) and internal rectal prolapse (IRP)[5,6].

A RC means that the anterior rectal wall protrudes forward during defecation, which is caused by weakness of the anterior rectal wall, the rectovaginal septum, and the posterior vaginal wall. The forward depression of the anterior rectal wall can be visualized by X-ray defecography and is palpable during digital rectal examination[7]. Vaginal delivery is the main cause of RC[8]. If the forward protruding part of the anterior rectal wall is greater than 0.5 cm, it is diagnosed as RC; 0.6-1.5 cm is grade I RC, 1.6-3.0 cm is grade II RC, and ≥ 3.0 cm is grade III RC[9].

IRP refers to a functional disease in which the rectal mucosa invades the rectal cavity during defecation. Sometimes it can be full-thickness intussusception, but the prolapsed part does not extend beyond the outer edge of the anus[10]. IRP was first proposed in 1903[11]. The main clinical manifestations of IRP include symptoms such as frequent bowel movements, anorectal swelling, incomplete defecation, and difficulty in passing stool[12]. IRP ratings are grade I if the rectal mucosal prolapse is above the anorectal ring, and intussusception depth is 3-15 mm; grade II if the rectal mucosal prolapse is at the level of the dentate line, and intussusception depth is 16-30 mm; and grade III if the rectal mucosal prolapse is at the level of the anal canal, and the intussusception depth is greater than 31 mm[13,14].

The surgical methods used for this disorder are diverse and difficult, and postope

From January 2017 to July 2019, female OOC patients with RC combined with IRP who met the inclusion criteria in Shenyang Anorectal Hospital and Dalian Third People’s Hospital were selected for treatment using the TST36 stapler. A total of 49 patients aged 35-71 years with an average age of 53.1 years and a medical history of 2-20 years were enrolled. The patients all had symptoms such as straining defecation, elongation of defecation time, hand-assisted defecation, and a feeling of incomplete evacuation that lasted more than 1 year.

Patients who met the Rome III criteria[23] and who had two or more of the following symptoms were included in the study: (1) More than 1/4 of defecations were laborious; (2) More than 1/4 of defecations consisted of a dry ball-shaped stool or hard stool; (3) More than 1/4 of defecations resulted in a feeling of incompleteness; (4) More than 1/4 of defecations had an anorectal obstruction/blockage; (5) More than 1/4 of defecations required manual assistance; and (6) Defecation less than 3 times/wk.

The patients must have symptoms for at least 6 mo before enrollment, and the duration should be more than 3 mo. The results of defecography and virtual defecography under 360° ultrasound in the rectal cavity suggested RC (> 3 cm) combined with IRP (> 10 mm)[24,25]; the balloon expulsion test was positive.

Patients with organic diseases such as irritable bowel syndrome, colonic slow transit constipation, and intestinal tumors were excluded.

The TST36STARR+ stapler made by Touchstone International Medical Science Company Limited (Suzhou, China) was used during surgery. In addition, the Anorectum Manometer (Laborie Medical Technologies, Inc., Mississauga, Canada) and the 360° intrarectal ultrasound instrument (Brüel and Kjær, Denmark) were also used.

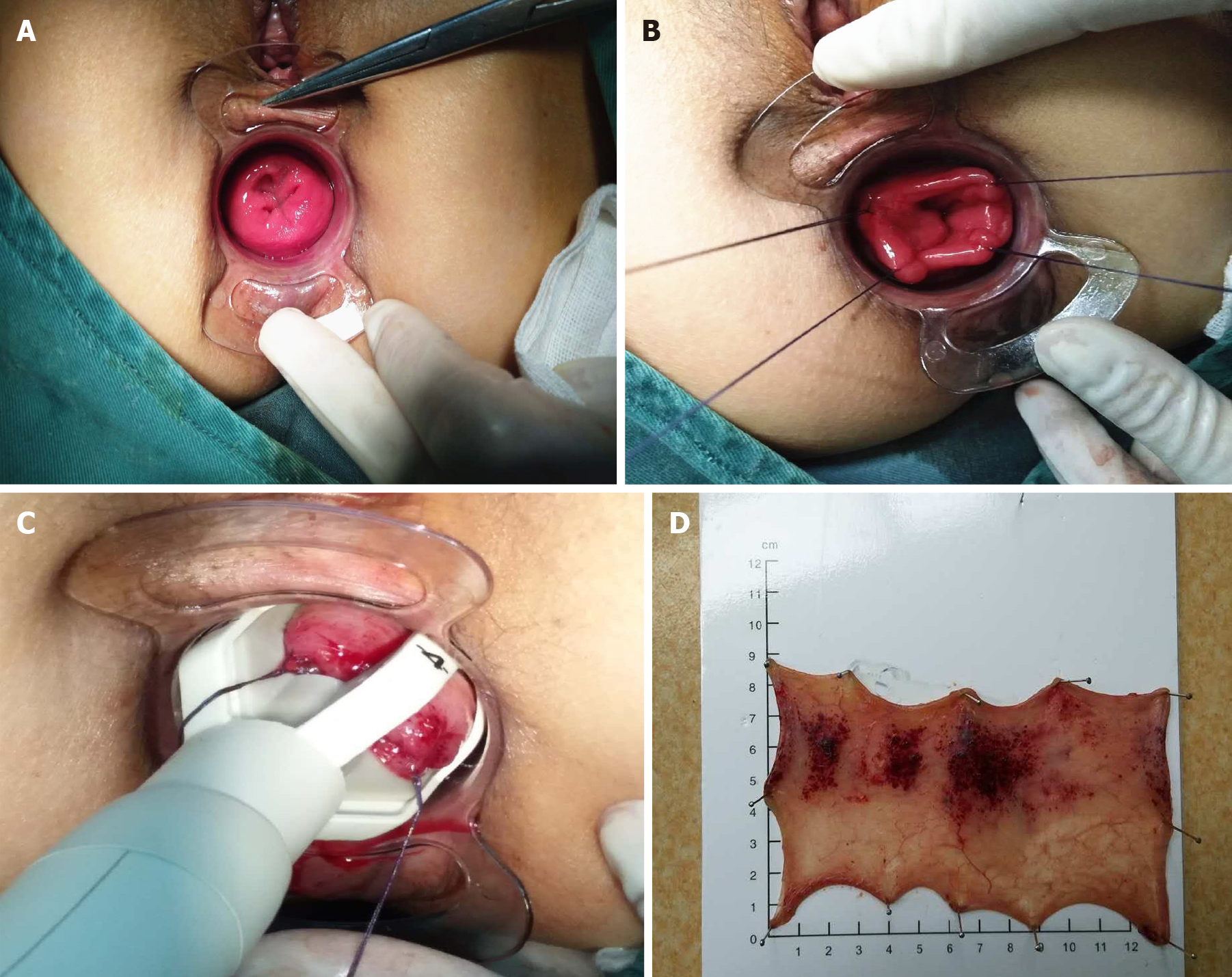

The procedure was carried out under sacral anesthesia. The lithotomy position was routinely disinfected to expand the anus, and the circular anal dilator matching the TST36STARR+ stapler was placed in the anal canal (Figure 1A). According to the degree of prolapse and the depth of the protrusion, parachute anastomosis was performed at the 1, 5, 9, and 11 o’clock positions using traction sutures, which reached the muscle layer (Figure 1B). The TST36 stapler was inserted, and the traction line was drawn through the visible window (Figure 1C). Before activating the stapler, the posterior vaginal wall was identified to prevent it from entering the stapler cavity. After activating the stapler, bleeding was observed, and hemostatic treatment was carried out. The excised specimen was examined to confirm whether it was full-thickness rectum (Figure 1D). After the operation, the patient fasted for 3 d to control defecation and was then given laxative treatment for 5 d to prevent constipation.

The efficacy was determined according to the Chinese Medical Association’s constipa

Defecation function in patients was evaluated by Longo’s obstructed defecation syndrome (ODS) score (Table 1)[27].

| Question | Response (score) | ||||

| Defecation frequency | 1-2 def every; 1–2 d (0) | 2 def/wk or 3 def/d (1) | 1 def/wk or 4 def/d (2) | < 1 def/wk or > 4 def/d (3) | |

| Straining intensity | N or light (0) | Moderate (1) | Intensive (2) | ||

| Straining extension | Short time (1) | Prolonged (2) | |||

| Sensation of incomplete evacuation | Never (0) | ≤ 1/wk (1) | 2/wk (2) | > 2/wk (3) | |

| Perineal discomfort | Never (0) | ≤ 1/wk (1) | 2/wk (2) | > 2/wk (3) | |

| Activity reduction | Never (0) | < 25% activity (1) | 25%-50% activity (4) | > 50% activity (6) | |

| Laxatives | Never (0) | < 25% def (1) | 25-50% def (3) | > 50% def (5) | Always (7) |

| Enemas | Never (0) | < 25% def (1) | 25-50% def (3) | > 50% def (5) | Always (7) |

| Digitation | Never (0) | < 25% def (1) | 25-50% def (3) | > 50% def (5) | Always (7) |

Statistic Package for Social Science 22.0 software (Armonk, NY, United States) was used for data analysis and processing, and the paired-samples t-test was used. When P < 0.05, the difference was considered statistically significant.

Of the 49 patients included in the study, 45 were cured, 4 improved, and no invalid patients were observed. The cure rate was 92%. Short-term postoperative complications included anastomotic bleeding at 3-9 d after the operation in 2 patients, who were discharged after hemostasis treatment. Five patients had urine retention after the operation. Long-term postoperative complications after 1 year of follow-up showed no anal stenosis, anal incontinence, or rectovaginal fistula, and no recurrences were observed.

The patients’ constipation symptoms were followed up and evaluated 1 year after treatment, and these symptoms were significantly relieved. The results showed that the postoperative ODS score, defecation frequency score, time/straining intensity, and sensation of incomplete evacuation were significantly reduced compared with these parameters before treatment, and the differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05, Table 2).

| Time | Cases | ODS score | Defecation frequency score | Defecation time/straining intensity score | Sensation of incomplete evacuation score |

| Before treatment | 49 | 17.71 ± 1.29 | 2.57 ± 0.50 | 3.39 ± 0.57 | 2.71 ± 0.46 |

| 1-yr follow-up | 49 | 6.29 ± 0.71 | 0.86 ± 0.8 | 1.43 ± 0.91 | 1.14 ± 0.84 |

| t value | 108.70 | 36.77 | 17.98 | 22.00 | |

| P value | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 |

The anal canal resting pressure and maximum squeeze pressure after the operation were lower than those before treatment, and the differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05). The initial and maximum defecation thresholds of patients after the operation were significantly lower than those before treatment, and the differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05, Table 3).

| Time | Anal canal resting pressure in mmHg | Maximum squeeze pressure in mmHg | Initial defecation threshold in mL | Maximum defecation threshold in mL |

| Before treatment | 76.14 ± 1.14 | 158.14 ± 1.74 | 86.86 ± 1.98 | 156.71 ± 1.68 |

| 1-yr follow-up | 75.39 ± 1.10 | 156.29 ± 1.85 | 66.14 ± 2.38 | 135.57 ± 1.86 |

| t value | 7.07 | 15.45 | 205.06 | 418.61 |

| P value | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 |

The postoperative RC scale, resting phase, and defecation phase in patients were significantly decreased compared with those before treatment, and the differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05, Table 4).

| Time | Cases | Scale | Resting phase in mm | Defecation phase in mm |

| Before treatment | 49 | III | 16.86 ± 1.26 | 38.86 ± 1.66 |

| 1-yr after operation | 49 | I | 5.43 ± 1.19 | 9.53 ± 1.23 |

| t value | 160.00 | 164.48 | ||

| P value | < 0.05 | < 0.01 |

OOC is abnormal defecation caused by abnormal function and morphology of the rectum and anal canal. The main clinical symptoms are difficulty in defecation, incomplete defecation, prolonged defecation time, and the need for manual assistance to defecate. It is commonly found in RC and IRP[11,28]. OOC seriously affects people’s normal work, study, and life, in particular female patients with constipation[29]. A variety of methods have been used to treat the disease, but due to a series of problems such as postoperative complications and high recurrence rates, satisfactory results have not been achieved.

The TST36 is a new type of large-capacity stapler with an average resected rectal tissue volume of 13.3 cm3 (range 8-19 cm3) and an average resected height of 5.18 cm (range 2.5-8 cm). The use of this stapler results in the removal of more tissue[30]. The TST36 stapler has an open large window, which provides the surgeon with a good view of the rectal tissue. The surgeon can control the volume of the prolapsed tissue to be removed through the traction line, to treat better RC and IRP at the same time. It avoids the shortcomings of blind cutting with traditional staplers and improves the safety and effectiveness of the operation[31].

Anal stenosis is the most troublesome postoperative complication, which can result in considerable pain in patients. Our research showed that surgery using the TST36 can avoid anal stenosis. This may be due to the selective removal of prolapsed and protruding rectal tissue under the direct field of view, which can maximize the preservation of normal mucosal bridges, thereby effectively preventing postoperative anal stenosis[32].

The TST36 stapler has an open window, which avoids the shortcomings of blind cutting when using traditional staplers. The surgeon can control the volume of the prolapsed tissue to be removed through the traction line and make corresponding adjustments, without removing or destroying the normal rectal mucosa, thereby effectively reducing the risk of rectovaginal fistula and postoperative hemorrhage caused by excessive removal of rectal mucosa.

The postoperative anal canal resting pressure and maximum squeeze pressure in patients were lower than those before treatment, but the differences were not clinically significant. This suggests that surgery using the TST36 stapler does not affect the function of the internal and external anal sphincter, and normal anal pressure can be maintained after the operation. The initial and maximum defecation thresholds in patients after the operation were significantly lower than those before treatment, and the differences were statistically significant. This suggests that the normal physiolo

The etiology of OOC is complicated. However, use of the TST36 stapler to perform surgery in patients with RC combined with IRP reduces the risk of complications, such as anal stenosis and postoperative hemorrhage, and protects the patient’s normal anal function, achieving satisfactory clinical effects. This treatment is worth promoting; however, further long-term follow-up observation is needed to determine its long-term efficacy.

The TST36 stapler is safe and effective in treating RC combined with IRP, and it is worthy of promotion for use in clinical work.

The most common causes of outlet obstructive constipation (OOC) are rectocele (RC) and internal rectal prolapse (IRP). The surgical methods for OOC are diverse and difficult, and the postoperative complications and recurrence rate are high, which results in both physical and mental pain in patients. With the continuous deepening of the surgeon’s concept of minimally invasive surgery and continuous in-depth research on the mechanism of OOC, the treatment concepts and surgical methods are conti

The TST36STARR+ stapler was used to treat patients with RC and IRP. The effects of this stapler in terms of morphology and function after surgery have not been well studied.

This study aimed to assess treatment outcome following use of the TST36 stapler in patients with RC combined with IRP.

Forty-nine female patients with RC and IRP who met the inclusion criteria were selected for treatment with the TST36 stapler, and their outcomes were analyzed.

The cure rate was 92%. The postoperative obstructed defecation syndrome score, defecation frequency score, time/straining intensity, and sensation of incomplete evacuation were significantly decreased compared with these parameters before treatment. The initial and maximum defecation thresholds in patients after surgery were significantly lower than those before treatment. The postoperative ratings of RC, resting phase, and defecation phase were significantly decreased compared with those before treatment.

The TST36 stapler is safe and effective in treating patients with RC combined with IRP, and it is worthy of promotion in clinical work.

The TST36 stapler is safe and effective in treating RC combined with IRP, and it is worthy of popularization and continuous improvement in clinical work.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Zimmerman M S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Yuan YY

| 1. | Chiarioni G, Whitehead WE, Pezza V, Morelli A, Bassotti G. Biofeedback is superior to laxatives for normal transit constipation due to pelvic floor dyssynergia. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:657-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 358] [Cited by in RCA: 297] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Maxion-Bergemann S, Thielecke F, Abel F, Bergemann R. Costs of irritable bowel syndrome in the UK and US. Pharmacoeconomics. 2006;24:21-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wald A, Scarpignato C, Kamm MA, Mueller-Lissner S, Helfrich I, Schuijt C, Bubeck J, Limoni C, Petrini O. The burden of constipation on quality of life: results of a multinational survey. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:227-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 260] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Piche T, Dapoigny M, Bouteloup C, Chassagne P, Coffin B, Desfourneaux V, Fabiani P, Fatton B, Flammenbaum M, Jacquet A, Luneau F, Mion F, Moore F, Riou D, Senejoux A; French Gastroenterology Society. [Recommendations for the clinical management and treatment of chronic constipation in adults]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2007;31:125-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Youssef M, Emile SH, Thabet W, Elfeki HA, Magdy A, Omar W, Khafagy W, Farid M. Comparative Study Between Trans-perineal Repair With or Without Limited Internal Sphincterotomy in the Treatment of Type I Anterior Rectocele: a Randomized Controlled Trial. J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;21:380-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Heinrich H, Sauter M, Fox M, Weishaupt D, Halama M, Misselwitz B, Buetikofer S, Reiner C, Fried M, Schwizer W, Fruehauf H. Assessment of Obstructive Defecation by High-Resolution Anorectal Manometry Compared With Magnetic Resonance Defecography. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1310-1317.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Mustain WC. Functional Disorders: Rectocele. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2017;30:63-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sangster P, Morley R. Biomaterials in urinary incontinence and treatment of their complications. Indian J Urol. 2010;26:221-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Li CY. Anorectal Diseases. Beijing: Higher Education Press, 2013: 190. |

| 10. | Wijffels NA, Collinson R, Cunningham C, Lindsey I. What is the natural history of internal rectal prolapse? Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:822-830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480-1491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3413] [Cited by in RCA: 3381] [Article Influence: 177.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Wijffels NA, Jones OM, Cunningham C, Bemelman WA, Lindsey I. What are the symptoms of internal rectal prolapse? Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:368-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Karlbom U, Graf W, Nilsson S, Påhlman L. The accuracy of clinical examination in the diagnosis of rectal intussusception. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1533-1538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pomerri F, Zuliani M, Mazza C, Villarejo F, Scopece A. Defecographic measurements of rectal intussusception and prolapse in patients and in asymptomatic subjects. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:641-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Frascio M, Stabilini C, Ricci B, Marino P, Fornaro R, De Salvo L, Mandolfino F, Lazzara F, Gianetta E. Stapled transanal rectal resection for outlet obstruction syndrome: results and follow-up. World J Surg. 2008;32:1110-1115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Formijne Jonkers HA, Poierrié N, Draaisma WA, Broeders IA, Consten EC. Laparoscopic ventral rectopexy for rectal prolapse and symptomatic rectocele: an analysis of 245 consecutive patients. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:695-699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Leanza V, Intagliata E, Leanza G, Cannizzaro MA, Zanghì G, Vecchio R. Surgical repair of rectocele. Comparison of transvaginal and transanal approach and personal technique. G Chir. 2013;34:332-336. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Kleeman SD, Karram M. Posterior pelvic floor prolapse and a review of the anatomy, preoperative testing and surgical management. Minerva Ginecol. 2008;60:165-182. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Ng ZQ, Levitt M, Tan P, Makin G, Platell C. Long-term outcomes of surgical management of rectal prolapse. ANZ J Surg. 2019;89:E231-E235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Pescatori M, Zbar AP. Tailored surgery for internal and external rectal prolapse: functional results of 268 patients operated upon by a single surgeon over a 21-year period*. Colorectal Dis. 2009;11:410-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Gültekin FA. Short term outcome of laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy for rectal and complex pelvic organ prolapse: case series. Turk J Surg. 2019;35:91-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Murphy PB, Schlachta CM, Alkhamesi NA. Surgical management for rectal prolapse: an update. Minerva Chir. 2015;70:273-282. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Drossman DA. The functional gastrointestinal disorders and the Rome III process. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1377-1390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1467] [Cited by in RCA: 1476] [Article Influence: 77.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Dietz HP, Beer-Gabel M. Ultrasound in the investigation of posterior compartment vaginal prolapse and obstructed defecation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012;40:14-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | van Gruting IMA, Stankiewicz A, Kluivers K, De Bin R, Blake H, Sultan AH, Thakar R. Accuracy of Four Imaging Techniques for Diagnosis of Posterior Pelvic Floor Disorders. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:1017-1024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Yang XQ. Interim criteria for diagnosis and treatment of constipation. Zhonghua Yixue Zazhi. 2000;80:491-492. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 27. | Boccasanta P, Venturi M, Calabro G, Maciocco M, Roviaro GC. Stapled transanal rectal resection in solitary rectal ulcer associated with prolapse of the rectum: a prospective study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:348-354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Schwandner O, Stuto A, Jayne D, Lenisa L, Pigot F, Tuech JJ, Scherer R, Nugent K, Corbisier F, Basany EE, Hetzer FH. Decision-making algorithm for the STARR procedure in obstructed defecation syndrome: position statement of the group of STARR Pioneers. Surg Innov. 2008;15:105-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Higgins PD, Johanson JF. Epidemiology of constipation in North America: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:750-759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 692] [Cited by in RCA: 675] [Article Influence: 32.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Naldini G, Fabiani B, Menconi C, Giani I, Toniolo G, Martellucci J. Tailored prolapse surgery for the treatment of hemorrhoids with a new dedicated device: TST Starr plus. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30:1723-1728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Boccasanta P, Agradi S, Vergani C, Calabrò G, Bordoni L, Missaglia C, Venturi M. The evolution of transanal surgery for obstructed defecation syndrome: Mid-term results from a randomized study comparing double TST 36 HV and Contour TRANSTAR staplers. Am J Surg. 2018;216:893-899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Zhang G, Liang R, Wang J, Ke M, Chen Z, Huang J, Shi R. Network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing the procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids, Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy and tissue-selecting therapy stapler in the treatment of grade III and IV internal hemorrhoids(Meta-analysis). Int J Surg. 2020;74:53-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Pechlivanides G, Tsiaoussis J, Athanasakis E, Zervakis N, Gouvas N, Zacharioudakis G, Xynos E. Stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR) to reverse the anatomic disorders of pelvic floor dyssynergia. World J Surg. 2007;31:1329-1335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |