Published online Mar 27, 2021. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v13.i3.303

Peer-review started: December 2, 2020

First decision: December 24, 2020

Revised: January 2, 2021

Accepted: January 14, 2021

Article in press: January 14, 2021

Published online: March 27, 2021

Processing time: 105 Days and 21.9 Hours

With advancements in laparoscopic technology and the wide application of linear staplers, sphincter-saving procedures are increasingly performed for low rectal cancer. However, sphincter-saving procedures have led to the emergence of a unique clinical disorder termed anterior rectal resection syndrome. Colonic pouch anastomosis improves the quality of life of patients with rectal cancer > 7 cm from the anal margin. But whether colonic pouch anastomosis can reduce the incidence of rectal resection syndrome in patients with low rectal cancer is unknown.

To compare postoperative and oncological outcomes and bowel function of straight and colonic pouch anal anastomoses after resection of low rectal cancer.

We conducted a retrospective study of 72 patients with low rectal cancer who underwent sphincter-saving procedures with either straight or colonic pouch anastomoses. Functional evaluations were completed preoperatively and at 1, 6, and 12 mo postoperatively. We also compared perioperative and oncological outcomes between two groups that had undergone low or ultralow anterior rectal resection.

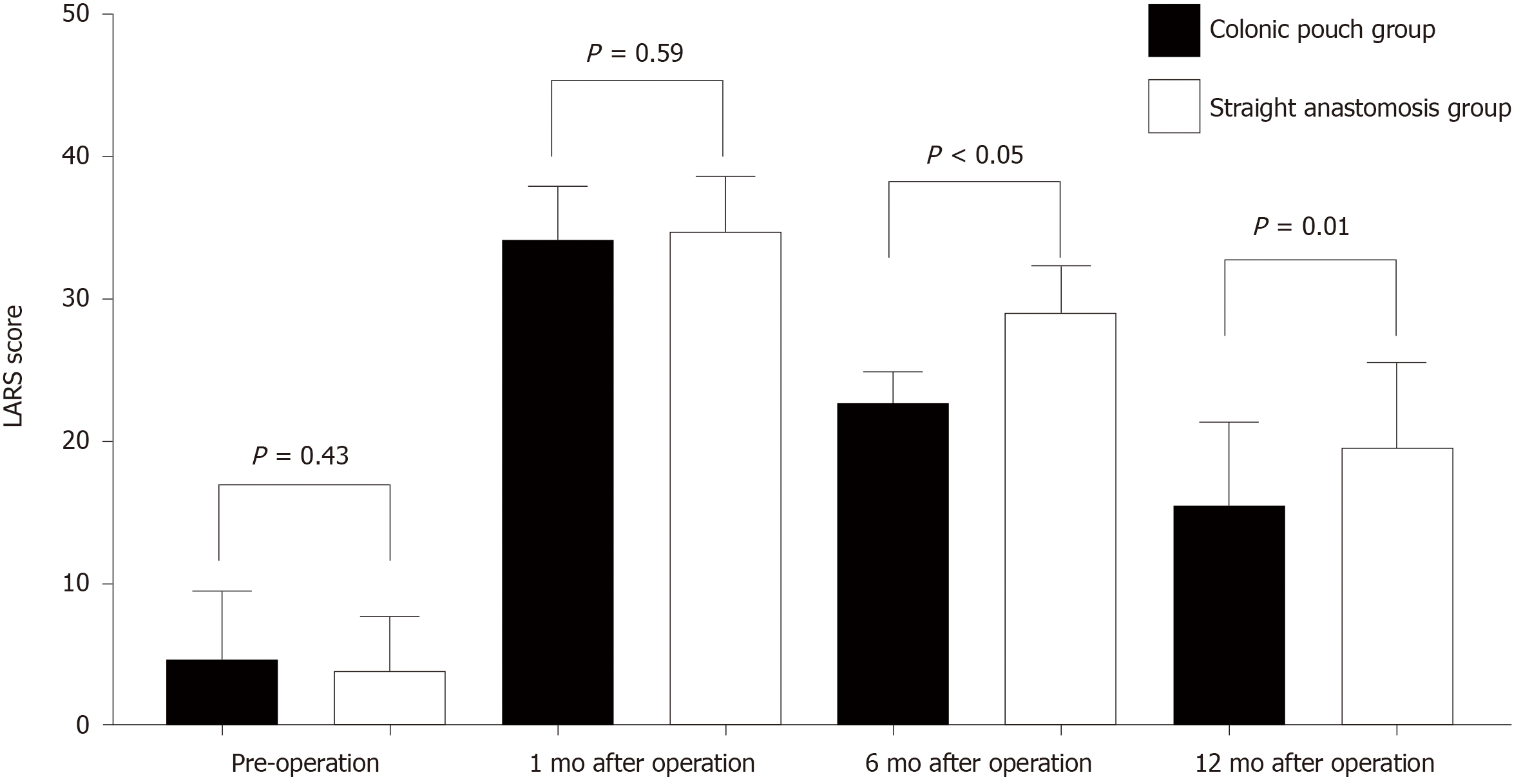

There were no significant differences in mean operating time, blood loss, time to first passage of flatus and excrement, and duration of hospital stay between the colonic pouch and straight anastomosis groups. The incidence of anastomotic leakage following colonic pouch construction was lower (11.4% vs 16.2%) but not significantly different than that of straight anastomosis. Patients with colonic pouch construction had lower postoperative low anterior resection syndrome scores than the straight anastomosis group, suggesting better bowel function (preoperative: 4.71 vs 3.89, P = 0.43; 1 mo after surgery: 34.2 vs 34.7, P = 0.59; 6 mo after surgery: 22.70 vs 29.0, P < 0.05; 12 mo after surgery: 15.5 vs 19.5, P = 0.01). The overall recurrence and metastasis rates were similar (4.3% and 11.4%, respectively).

Colonic pouch anastomosis is a safe and effective procedure for colorectal reconstruction after low and ultralow rectal resections. Moreover, colonic pouch construction may provide better functional outcomes compared to straight anastomosis.

Core Tip: With the increased use of sphincter-saving procedures, improvements of the quality of life of patients undergoing low or ultralow anterior rectal resection have become increasingly important. Our study demonstrates that the use of colonic pouch anastomosis gives a superior functional result when compared with traditional straight anastomosis for low rectal cancer. Therefore, colonic pouch anastomosis is a favorable option for patients undergoing low anterior or ultralow anterior resection.

- Citation: Chen ZZ, Li YD, Huang W, Chai NH, Wei ZQ. Colonic pouch confers better bowel function and similar postoperative outcomes compared to straight anastomosis for low rectal cancer. World J Gastrointest Surg 2021; 13(3): 303-314

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v13/i3/303.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v13.i3.303

Low rectal cancer is loosely defined as tumors occurring in the distal rectum within 6 cm of the anal ring[1]. Abdominoperineal resection was historically the procedure of choice for such cases. However, with advancements in laparoscopic technology and the wide application of linear staplers[2,3], sphincter-saving procedures are increasingly performed leading to a marked decline in abdominoperineal resection for low rectal cancer in clinical practice[4]. However, sphincter-saving procedures have led to the emergence of a unique clinical disorder termed anterior rectal resection syndrome (ARS), which is multidimensional bowel dysfunction syndrome, including fecal incontinence, urgency, frequent bowel movements, and clustering[5]. Ninety percent of patients have varying degrees of postoperative ARS, and up to 41% patients have major ARS[6,7]. However, ARS is primarily a clinical diagnosis based on symptoms rather than objective scoring systems, which has led to a substantial underestimation of ARS prevalence in clinical practice[8].

Colonic pouch anastomosis has been used for over 34 years for colorectal reconstruction after rectal resection[9,10]. Due to limitations of surgical technique, the procedure is used primarily in patients with lesions > 7 cm from the anal margin. With an improved understanding of the rectal margin[11] and the wide application of laparoscopic and stapling technology, low and ultralow anterior rectal resections are being increasingly performed[12]. Meanwhile, the incidence and severity of ARS have increased correspondingly.

Tumor location and the level of anastomosis are significant factors that determine bowel function[13,14]. Colonic pouch anastomosis improves the quality of life of patients with rectal cancer > 7 cm from the anal margin[15]. However, whether colonic pouch anastomosis can reduce the incidence of ARS in patients with low rectal cancer is unknown. The aim of this study was to compare the postoperative and oncological outcomes, bowel function, and complications of straight and colonic pouch anastomoses in low rectal cancer.

We conducted a retrospective study at the Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, China. Our hospital, whose operation volume for rectal cancer is up to 500 cases every year, is a high-volume center for such surgery. The perioperative and follow-up data of patients with low rectal cancer who underwent surgery at our department from January 2017 to January 2020 were analyzed.

Inclusion criteria were: (1) Rectal adenocarcinoma with the lower margin < 6 cm from the anal margin; and (2) Planned curative sphincter-saving rectal resection.

Exclusion criteria were: (1) Emergency surgery; (2) Previous major abdominal or pelvic surgery; (3) Preoperative anal incontinence; (4) Age ≥ 80 years; (5) Receipt of neoadjuvant chemoradiation; and (6) Invasion of adjacent organs or distant metastasis.

All patients underwent a thorough preoperative evaluation that included routine blood investigations, assays of tumor markers such as carcinoembryonic antigen, colonoscopic biopsy; pelvic magnetic resonance imaging, and/or endorectal ultrasound. The distance between the lower margin of the rectal tumor and the anal margin was determined by digital rectal examination and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging. Tumor staging was done according to the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging manual[16]. All patients received mechanical bowel preparation with 2 L of polyethylene glycol 12-16 h preoperatively and were allowed a regular diet until midnight before surgery.

All included patients underwent transabdominal R0 low anterior (LAR) or ultralow anterior resection (ULAR), including complete mesorectal excision and anal sphincter preservation[17]. To ensure adequate perfusion of the proximal colon, the inferior mesenteric artery was ligated distal to the left colic artery. The decision to perform ULAR was made when the tumor was too low to perform distal rectal division through the abdominal approach.

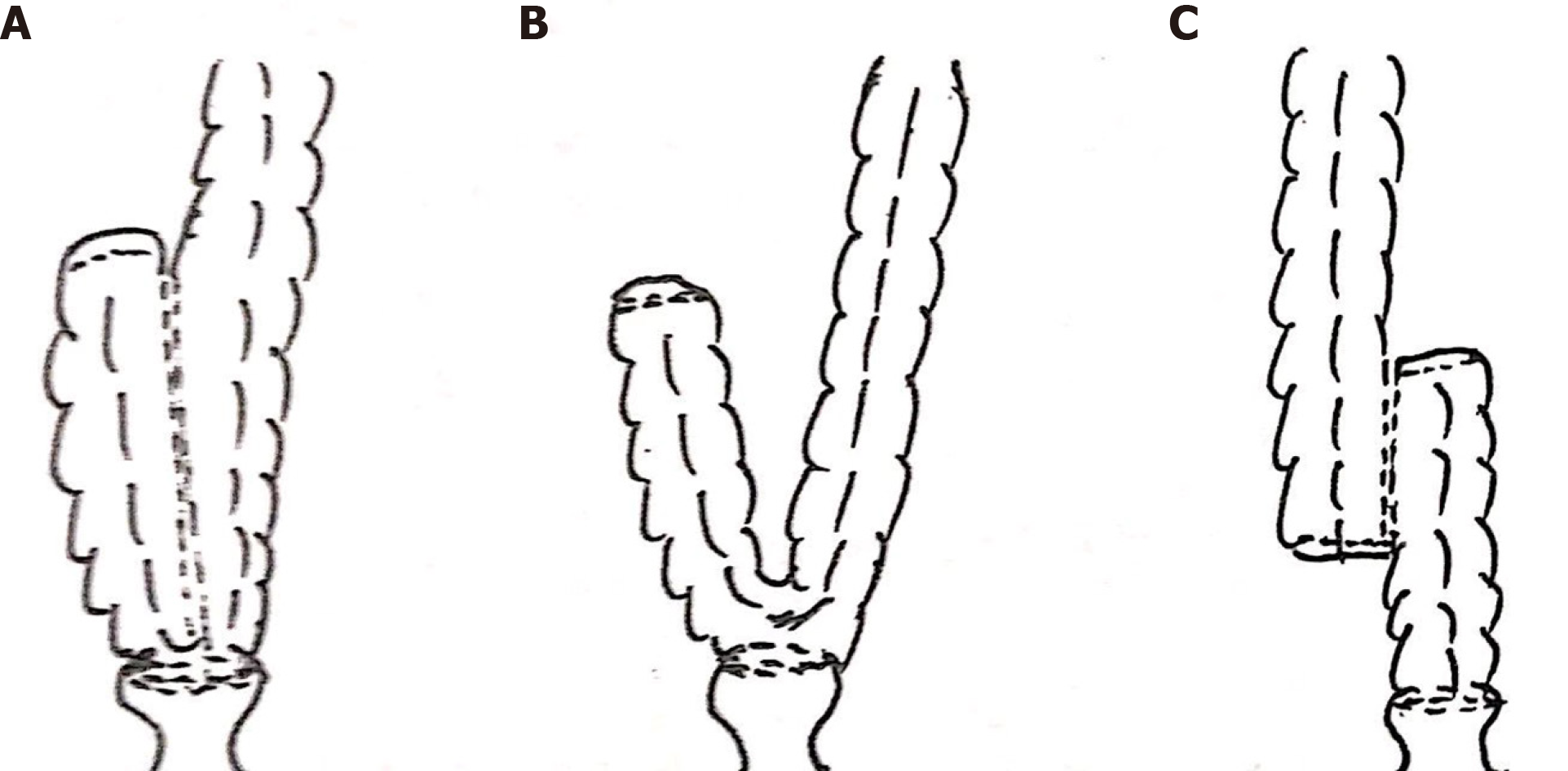

Colorectal reconstruction was done using the double staple technique with or without a colonic pouch. The decision to construct a colonic pouch was made by the operating surgeon based on preoperative and intraoperative findings including: (1) Sufficient colon length; (2)Adequate pelvic volume; (3) Normal colon bulk; and (4) Patient’s physical condition. The colonic pouch was constructed in either a J-shape, H-shape, or side-to-end anastomosis. The J-pouch was made by folding the colon and creating a side-to-side anastomosis with a stapler introduced through the apex of the pouch (Figure 1A). Side-to-end anastomosis was constructed by folding the colon (Figure 1B). The H-pouch was created by dividing the colon alone without its mesocolon, and performing side-to-side anastomosis with a stapler (Figure 1C). Next, a circular stapler was used to anastomose the colonic pouch to the anal canal. The length of the colonic pouch was approximately 5-6 cm in all patients. Temporary loop ileostomy was constructed in patients at high risk of anastomotic leak.

Perioperative broad-spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis (cefuroxime) was begun during the induction of anesthesia and continued for at least 24 h after surgery. Revisions of the antibiotic regimen were determined by the surgeon in response to the patient’s condition. All patients were allowed to drink water on the first postoperative day, soup on the second day, and to consume nutritional powder on the third day. These milestones were adjusted according to the recovery of bowel function. We often encouraged all patients to get out of bed on the first postoperative to facilitate bowel function.

All patients were evaluated at 3-6 mo in the outpatient department. Routine blood tests (including tumor markers) were done every 3 mo, a computed tomography scan was completed every 6 mo, and a colonoscopy was performed annually. Patients having either stage II disease with high-risk factors or stage III disease received 6-8 cycles of chemotherapy (oxaliplatin plus capecitabine)[18]. If tumor margins were positive on histopathologic examination, we usually suggested postoperative radiotherapy. However, all included patients did not receive postoperative radiotherapy because Ro resection was performed for those patients. Ileostomy was closed 2 mo postoperatively and after confirmation of the integrity of the anastomosis. Functional outcomes were assessed by interviewing patients during the office visits using a standardized low anterior resection syndrome (LARS) questionnaire at 1, 6, and 12 mo after ileostomy closure[19].

SPSS statistical software for Windows (version 23.0) was used for data analysis (SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States). Ordinal variables were compared using Wilcoxon’s rank sum test or Wilcoxon’s signed rank test, as appropriate. Nominal variables were compared using the Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. A two-sided P value of > 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

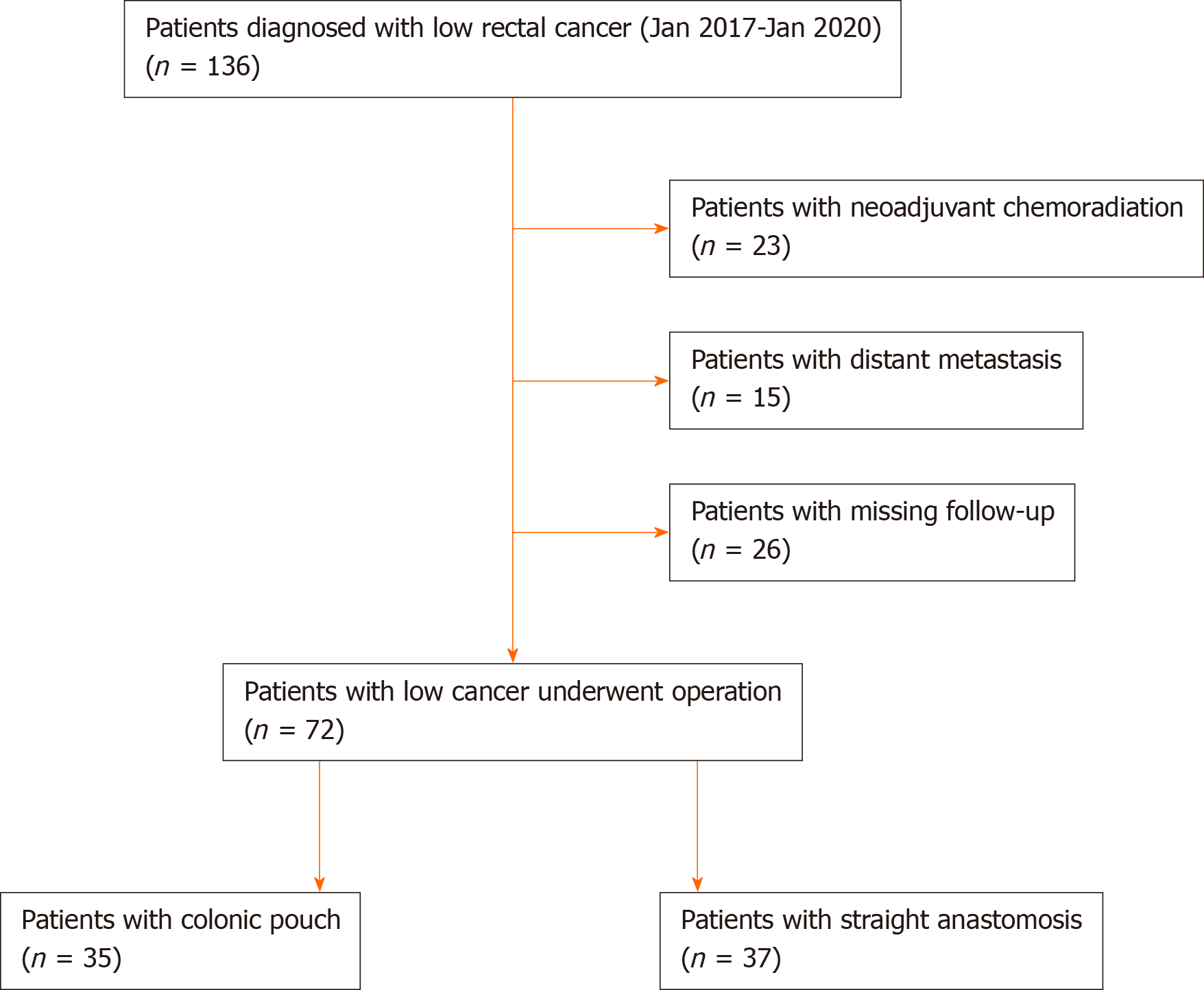

Data of 136 patients with low rectal cancer treated during the study period were retrieved. Among these, 23 patients received neoadjuvant chemoradiation, 15 patients did not receive surgery due to distant metastasis, and 26 patients did not complete postoperative follow-up. Consequently, 72 patients satisfying the selection criteria were included in this study (Figure 2).

Of 72 patients, 7 underwent ULAR, colonic pouch construction, and coloanal anastomosis with double-stapled technique. The remaining 65 patients underwent LAR with double-stapled anastomosis. Complete mesorectal excision was performed in all cases[16] and was confirmed on histopathology. Temporary loop ileostomy was constructed during the primary surgery for 52 patients (colonic pouch: n = 28, straight anastomosis: n = 24) at high risk of anastomotic leakage.

Colonic pouches were constructed in 35 patients. Different colonic pouch types included J-pouch (n = 27), H-pouch (n = 2), and side-to-end anastomosis (n = 6). The H-pouch was used in the setting of a narrow pelvis. In six patients who underwent total laparoscopic radical resection of rectal cancer, we performed side-to-end anastomosis because it was difficult to create the J-pouch with the total laparoscopic technique (Table 1).

| Character | Colonic pouch | Straight anastomosis | P value |

| Number | 35 | 37 | - |

| Sex, male/female | 18/17 | 15/22 | 0.35 |

| Age in yr, median (range) | 58.1 (30.0-79.0) | 61.3 (41.0-76.0) | 0.25 |

| BMI | 23.4 | 23.6 | 0.88 |

| Temporary stoma, n (%) | 28 (80) | 24 (67) | 0.89 |

| Tumor height above anal verge in cm, median (range) | 3.9 (2.0-6.0) | 4.9 (3.0-6.0) | < 0.05 |

| Anastomotic height above anal verge in cm, median (range) | 1.9 (1.0-4.0) | 2.5 (1.0-4.0) | < 0.05 |

| J pouch/H pouch/side-to-end anastomosis | 27/2/6 | - | - |

| TNM stage, I/II/III/IV | 17/9/9/0 | 12/14/11/0 | 0.35 |

| Distal resection margin in cm, mean ± SD | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 0.93 |

| No. collected lymph nodes, mean ± SD | 15.1 ± 4.9 | 14.4 ± 2.6 | 0.52 |

| Proximal resection margin in cm, mean ± SD | 11.6 ± 2.7 | 11.4 ± 2.3 | 0.37 |

| Postoperative chemotherapy | 16 | 18 | 0.80 |

Comparisons of various parameters between patients with colonic pouch and straight anastomoses are shown in Table 2. There were no significant differences between the two groups in blood loss, operation time, postoperative complications, and duration of hospitalization.

| Parameter | Colonic pouch | Straight anastomosis | P value |

| Operating time in min, mean ± SD | 267.9 ± 58.6 | 247.8 ± 48.5 | 0.12 |

| Blood loss in mL, mean ± SD | 77.7 ± 69.2 | 95.7 ± 91.9 | 0.35 |

| Flatus passage in d, mean ± SD | 3.0 ± 1.3 | 2.9 ± 1.5 | 0.81 |

| Excrement passage in d, mean ± SD | 3.9 ± 1.3 | 3.7 ± 1.4 | 0.51 |

| Hospitalization in d, mean ± SD | 9.4 ± 5.3 | 10.3 ± 4.9 | 0.44 |

| Postoperative complications, n (%) | 0.55 | ||

| Total | 11 (31.4) | 13 (35.1) | |

| Anastomotic leakage | 4 (11.4) | 6 (16.2) | |

| Lung infection | 1 (2.9) | 1 (2.7) | |

| Urinary retention | 2 (5.7) | 1 (2.7) | |

| Chyle fistula | 1 (2.9) | 0 | |

| Bowel obstruction | 0 | 3 (8.1) | |

| Wound infection | 2 (5.7) | 1 (2.7) | |

| Death | 1 (2.9) | 1 (2.7) |

Four and six patients developed anastomotic leakage in the colonic pouch group (11.4%) and the straight anastomosis group (16.2%), respectively. Anastomotic leakage was managed by antibiotics only (colonic pouch group = 2, straight anastomosis group = 3) and by creation of a loop ileostomy (colonic pouch group = 2, straight anastomosis group = 3). Two patients died; one each from the colonic pouch group and the straight anastomosis group. The patient in the colonic pouch group died due to a chylous fistula complicated by an intra-abdominal infection. The patient in the straight anastomosis group died due to an acute intestinal obstruction.

Four and three patients in the colonic pouch and straight anastomosis groups, respectively, did not undergo ileostomy closure; consequently, their postoperative LARS scores were not determined. There were no significant differences in the LARS scores before surgery (colonic pouch: straight anastomosis = 4.71:3.89, P = 0.43) and 1 mo after surgery (colonic pouch: straight anastomosis = 34.2:34.7, P = 0.59) between the two groups. However at 6 and 12 mo after surgery, functional outcomes of the colonic pouch group were better than straight anastomosis group (6 mo: colonic pouch: straight anastomosis = 22.70:26.0, P < 0.05; 12 mo: colonic pouch: straight anastomosis = 15.5 vs 19.5 P = 0.01) (Figure 3). There were no significant differences in stool continence and urgency, except for stool frequency (Table 3).

| Parameter | Colonic pouch group, n = 35 | Straight anastomosis, n = 37 | |||||||||

| Preop | 1 mo | 6 mo | 12 mo | Preop | 1 mo | 6 mo | 12 mo | 1P value | 2P value | 3P value | |

| Continence, n | 0.69 | 0.44 | 0.40 | ||||||||

| Normal | 35 | 2 | 15 | 17 | 37 | 5 | 10 | 18 | |||

| Incontinent to gas | 0 | 8 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 6 | 2 | |||

| Occasional minor leak | 0 | 17 | 10 | 11 | 0 | 19 | 16 | 14 | |||

| Frequent major soiling | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | |||

| Total incontinence | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Absence of feces | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Urgency, n | |||||||||||

| Stool frequency, mean ± SD | 5.0 ± 2.5 | 10.6 ± 2.3 | 5.2 ± 2.8 | 3.4 ± 2.0 | 4.6 ± 2.8 | 11.0 ± 2.2 | 7.4 ± 2.9 | 4.3 ± 1.9 | 0.43 | < 0.05 | 0.07 |

| Perineal irritation | 8 | 29 | 20 | 16 | 9 | 30 | 27 | 22 | 0.46 | 0.18 | 0.54 |

| Incomplete defecation | 15 | 30 | 24 | 15 | 16 | 32 | 30 | 23 | 0.61 | 0.24 | 0.26 |

| Fragmentation | 10 | 28 | 22 | 15 | 14 | 30 | 26 | 22 | 0.79 | 0.61 | 0.37 |

| Antidiarrheal medication | 9 | 29 | 23 | 19 | 10 | 29 | 25 | 21 | 0.28 | 0.95 | 0.90 |

| Use of laxatives | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - |

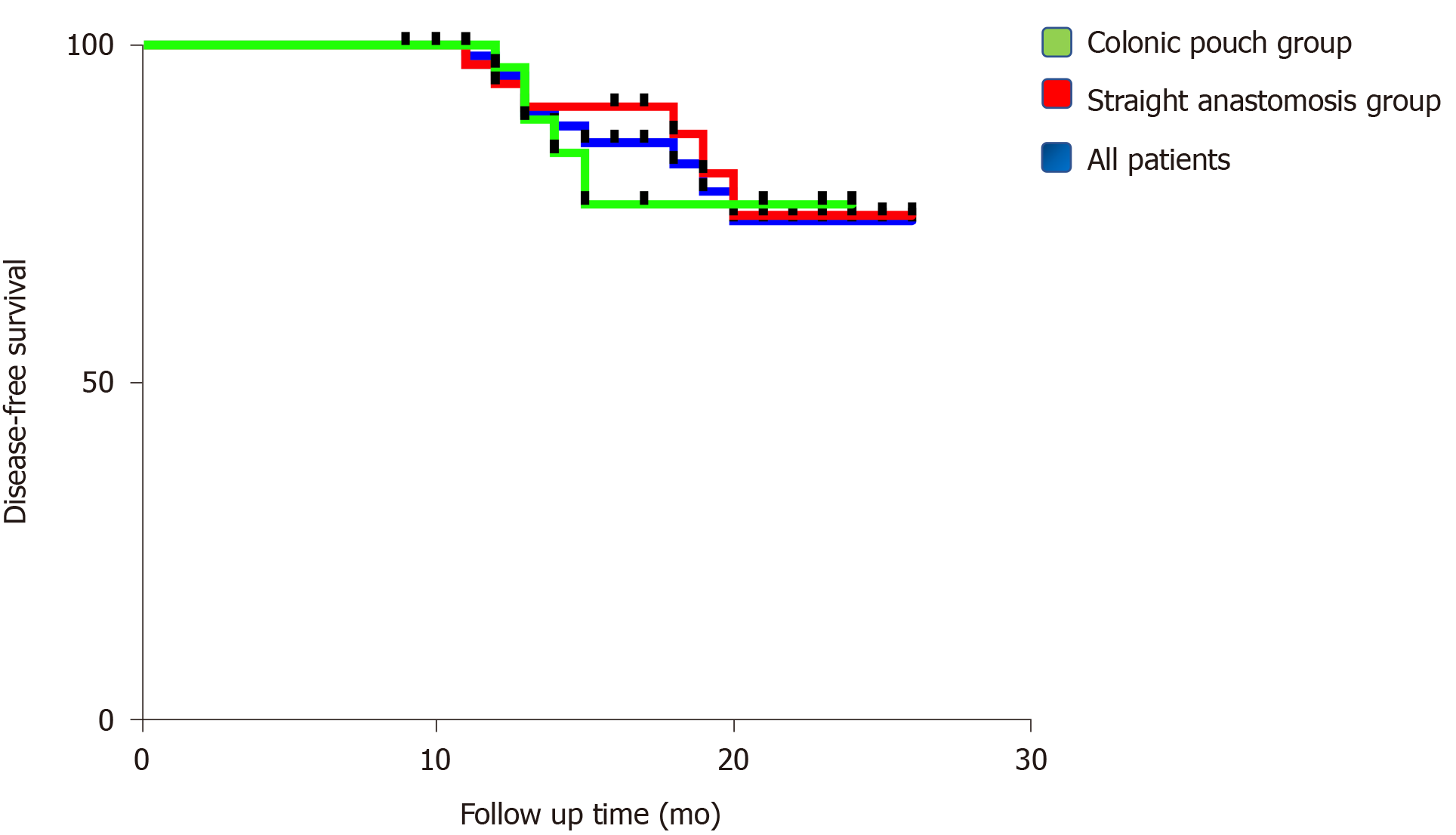

Ro resection was performed for all patients with low rectal cancer, which was confirmed by pathological analysis. There were no significant differences in numbers of positive lymph nodes and surgical margins that included distal and proximal resection margins (Table 1). The mean follow-up period of the entire cohort was 16.1 mo (range 9.0-26.0) [colonic pouch group: 14.5 mo (range 9.0-24.0); straight anastomosis group: 17.7 mo (range 10.0-26.0)]. The overall local recurrence rate was 4.3% (3/70). One patient in the straight anastomosis group with T4N2 developed local recurrence, and two patients in the colonic pouch group with T2N0 and T4N0 developed local recurrence. However, the overall metastasis rate was 11.4% (8/70). Three patients in the colonic pouch group developed pulmonary or hepatic metastasis. In the straight anastomosis group, five patients developed pulmonary or hepatic metastasis (Table 4). The disease-free survival rates of recurrence and metastasis were similar between the two groups (P = 0.63) (Figure 4).

| TNM stage | Number | Local recurrences | Metastasis | |||

| CP group | SA group | CP group | SA group | CP group | SA group | |

| T1N0 | 7 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| T2N0 | 10 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| T3N0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| T4N0 | 5 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| T1N1/2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| T2N1/2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| T3N1/2 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| T4N1/2 | 6 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

The use of a colonic pouch after rectal resection was first reported by Lazorthes et al[9] and Parc et al[10] in 1986. The purpose of the colonic pouch is to serve as a rectum-like stool reservoir to improve bowel function. In the study by Lazorthes et al[9], the distance of the tumor from the anal verge was > 7 cm. In subsequent studies, the median tumor height above the anal verge has been 7 cm[20,21]. In contrast, in the present study, the median tumor height above the anal verge was 3.9 cm (2.0-6.0 cm). Therefore, we explored the technical safety, functional results, and oncological safety of colonic pouch anastomosis after low and ultralow rectal resection.

In this study, there were no significant differences in operating time, blood loss, and time to first passage of flatus and excrement between the two groups. However, colonic pouch construction is more time-consuming than straight anastomosis. This could be explained by the fact that shaping an additional colonic pouch is more complex than performing straight end-to-end anastomosis. At the same time, we found that the most difficult challenge in constructing colonic pouch-anal anastomosis is narrow pelvic width. The colonic pouch is relatively bulky and difficult to fit in a narrow pelvis up to the anal canal. Therefore, we modified the pouch shape and constructed an H-pouch in two patients with narrow pelvic widths. Harris et al[22] also suggested that narrow pelvic width is the primary reason for failed colonic pouch construction. Consequently, a thorough preoperative evaluation, including BMI and radiological imaging, should be completed for patients awaiting colonic pouch construction.

The current study found an anastomotic leakage rate in the colonic pouch group of 11.4% (4/35) compared to 16.2% (6/37) in the straight group; the difference was not statistically significant. The prevalence of anastomotic leakages varies from 5%-19% for colorectal or coloanal so that anastomotic leakage rate in our study is high[23], which is mainly caused by low tumor height that is an independent predictive risk factor for anastomotic leakage[24]. Hallböök et al[20] reported that the incidence of anastomotic leakage was lower in colonic pouch anastomosis (15% vs 3%, P < 0.05), while Pucciarelli et al[21] found that anastomotic leakage incidence rates after colonic and straight anastomosis were similar. We believe that the microcirculation at the apex of the pouch is better preserved compared with straight anastomosis[25]. However, the presence of a covering stoma may reduce the severity and symptoms of anastomotic leakage and may significantly affect the validity of the comparison of the two techniques[26]. There were no significant differences between our two groups in other perioperative complications, which is consistent with the findings of other studies[21,27]. Therefore, based on the findings of this study, we conclude that colonic pouch anastomosis is safe for reconstruction after low or ULAR.

In this study, we observed better bowel function in the colonic pouch group than the straight anastomosis group at 6 and 12 mo postoperatively, especially in regard to stool continence. A reduction in stool frequency and improved continence were found in a J-pouch group in a small trial (but no difference in urgency)[27]. Liang et al[28] reported that anorectal function after colonic pouch anastomosis was better than after straight anastomosis at 3 mo after operation. A randomized study including 100 patients showed that bowel function following colonic pouch anastomosis was better than that after straight anastomosis, especially during the first two postoperative months[20]. However, in our study, better bowel function for colonic pouch occurred in 6 mo after operation, which was due to low colorectal or coloanal anastomosis that led to severe symptoms of rectal stimulation between the two groups, especially in 1 mo after surgery. As the symptom of rectal stimulation subsides, colonic pouch is better for bowel function than straight anastomosis. The superior anorectal function of colonic pouch compared to straight anastomosis was thought to be due to a larger pouch capacity, which reduces stool frequency and increases compliance.

The recurrence rate in our study was comparable to previous reports, although only 70 patients were evaluated. Kim et al[29] reported a local recurrence rate of 4.1%, a metastasis rate of 8.2%, and a local recurrence combined with metastasis rate of 4.1%. A study of 56 patients showed that the local recurrence rate was 1.7% after 2 yrs of follow-up[11]. Similar to the findings of previous studies, there were no significant differences in recurrence or metastasis rates between colonic pouch and straight anastomoses in the present study. The rate of local recurrence was in fact comparable to that of abdominoperineal resection because the mesorectum was completely excised[29]. At the same time, Moore et al[11] revealed that distal margins ≤ 1 cm do not seem to compromise oncological outcome. Hence, low or ULAR has safe oncological outcomes, and the use of colonic pouch anastomosis does not increase the risks of local recurrence or metastasis.

This study has some limitations. First, it is a retrospective study with a small sample, so the conclusion needs to be further confirmed by a prospective study with a larger sample in the future. Second, the pouch patients had a significantly low tumor height and anastomosis height, which may be a confounding effect. Patients who underwent LAR or ULAR have a small remaining rectal volume and almost no bowel storage function. Therefore, this effect may not affect the primary outcome. At the same time, the lower the tumor and anastomotic location, the worse the intestinal function[30,31]. However, colonic pouch had better bowel function than straight anastomosis even though the colonic pouch group had a lower tumor and anastomosis location, which further confirms that colonic pouch is better for bowel function compared with straight anastomosis.

Patients undergoing surgery for low rectal cancer often have major ARS and should be offered the best postoperative outcome. Our study demonstrates that the use of colonic pouch anastomosis gives a superior functional result when compared with traditional straight anastomosis for low rectal cancer. With the increased use of sphincter-saving procedures, improvements of the quality of life of patients undergoing LAR or ULAR become increasingly important. Despite imperfect evacuation, the overall well-being of bowel function was significantly better in the pouch group. Therefore, colonic pouch anastomosis is a good option for patients undergoing LAR or ULAR.

This study demonstrated that colonic pouch anastomosis is a safe and effective alternative to straight anastomosis after LAR and ULAR. Moreover, colonic pouch anastomosis may provide better postoperative functional outcomes. Future prospective randomized trials are required to validate the findings of this study.

Colonic pouch anastomosis improves the quality of life of patients with rectal cancer > 7 cm from the anal margin. But whether colonic pouch anastomosis can reduce the incidence of rectal resection syndrome in patients with low rectal cancer (within 6 cm of the anal ring) is unknown.

Identify the role of colonic pouch for low rectal cancer.

Compare postoperative and oncological outcomes and bowel function of straight and colonic pouch anal anastomoses after resection of low rectal cancer.

We conducted a retrospective study of 72 patients with low rectal cancer who underwent sphincter-saving procedures with either straight or colonic pouch anastomoses. Then, we explored the technical safety, functional results, and oncological safety of colonic pouch anastomosis after low and ultralow rectal resection by comparing with straight anastomoses.

There were no significant differences in postoperative and oncological outcomes between the colonic pouch and straight anastomosis groups. However, patients with colonic pouch construction had lower postoperative low anterior resection syndrome scores than the straight anastomosis group, suggesting better bowel function.

Colonic pouch anastomosis is a safe and effective alternative to straight anastomosis after low and ultralow rectal resection. Moreover, colonic pouch anastomosis may provide better postoperative functional outcomes.

Future prospective randomized trials are required to validate the findings of this study.

We would like to express our gratitude to all those who contributed to the study. This work was supported by the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: Chong CS, Kapritsou M, Vasudevan A, Zhang H S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Rullier E, Denost Q, Vendrely V, Rullier A, Laurent C. Low rectal cancer: classification and standardization of surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:560-567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sato H, Maeda K, Hanai T, Matsumoto M, Aoyama H, Matsuoka H. Modified double-stapling technique in low anterior resection for lower rectal carcinoma. Surg Today. 2006;36:30-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lusch A, Bucur PL, Menhadji AD, Okhunov Z, Liss MA, Perez-Lanzac A, McDougall EM, Landman J. Evaluation of the impact of three-dimensional vision on laparoscopic performance. J Endourol. 2014;28:261-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tilney HS, Heriot AG, Purkayastha S, Antoniou A, Aylin P, Darzi AW, Tekkis PP. A national perspective on the decline of abdominoperineal resection for rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2008;247:77-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Keane C, Wells C, O'Grady G, Bissett IP. Defining low anterior resection syndrome: a systematic review of the literature. Colorectal Dis. 2017;19:713-722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bregendahl S, Emmertsen KJ, Lous J, Laurberg S. Bowel dysfunction after low anterior resection with and without neoadjuvant therapy for rectal cancer: a population-based cross-sectional study. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:1130-1139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Croese AD, Lonie JM, Trollope AF, Vangaveti VN, Ho YH. A meta-analysis of the prevalence of Low Anterior Resection Syndrome and systematic review of risk factors. Int J Surg. 2018;56:234-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 221] [Article Influence: 31.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jimenez-Gomez LM, Espin-Basany E, Trenti L, Martí-Gallostra M, Sánchez-García JL, Vallribera-Valls F, Kreisler E, Biondo S, Armengol-Carrasco M. Factors associated with low anterior resection syndrome after surgical treatment of rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2017;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lazorthes F, Fages P, Chiotasso P, Lemozy J, Bloom E. Resection of the rectum with construction of a colonic reservoir and colo-anal anastomosis for carcinoma of the rectum. Br J Surg. 1986;73:136-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 339] [Cited by in RCA: 272] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Parc R, Tiret E, Frileux P, Moszkowski E, Loygue J. Resection and colo-anal anastomosis with colonic reservoir for rectal carcinoma. Br J Surg. 1986;73:139-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 320] [Cited by in RCA: 250] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Moore HG, Riedel E, Minsky BD, Saltz L, Paty P, Wong D, Cohen AM, Guillem JG. Adequacy of 1-cm distal margin after restorative rectal cancer resection with sharp mesorectal excision and preoperative combined-modality therapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:80-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Koyama M, Murata A, Sakamoto Y, Morohashi H, Takahashi S, Yoshida E, Hakamada K. Long-term clinical and functional results of intersphincteric resection for lower rectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21 Suppl 3:S422-S428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Juul T, Ahlberg M, Biondo S, Espin E, Jimenez LM, Matzel KE, Palmer GJ, Sauermann A, Trenti L, Zhang W, Laurberg S, Christensen P. Low anterior resection syndrome and quality of life: an international multicenter study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57:585-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 238] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Juul T, Elfeki H, Christensen P, Laurberg S, Emmertsen KJ, Bager P. Normative Data for the Low Anterior Resection Syndrome Score (LARS Score). Ann Surg. 2019;269:1124-1128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 23.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ribi K, Marti WR, Bernhard J, Grieder F, Graf M, Gloor B, Curti G, Zuber M, Demartines N, Andrieu C, Bigler M, Hayoz S, Wehrli H, Kettelhack C, Lerf B, Fasolini F, Hamel C; Swiss group for clinical cancer research; section surgery. Quality of Life After Total Mesorectal Excision and Rectal Replacement: Comparing Side-to-End, Colon J-Pouch and Straight Colorectal Reconstruction in a Randomized, Phase III Trial (SAKK 40/04). Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26:3568-3576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Weiser MR. AJCC 8th Edition: Colorectal Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25:1454-1455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 294] [Cited by in RCA: 648] [Article Influence: 92.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Vignali A, Elmore U, Milone M, Rosati R. Transanal total mesorectal excision (TaTME): current status and future perspectives. Updates Surg. 2019;71:29-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Weitz J, Koch M, Debus J, Höhler T, Galle PR, Büchler MW. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2005;365:153-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 862] [Cited by in RCA: 946] [Article Influence: 47.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Carrillo A, Enríquez-Navascués JM, Rodríguez A, Placer C, Múgica JA, Saralegui Y, Timoteo A, Borda N. Incidence and characterization of the anterior resection syndrome through the use of the LARS scale (low anterior resection score). Cir Esp. 2016;94:137-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hallböök O, Påhlman L, Krog M, Wexner SD, Sjödahl R. Randomized comparison of straight and colonic J pouch anastomosis after low anterior resection. Ann Surg. 1996;224:58-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 356] [Cited by in RCA: 290] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Pucciarelli S, Del Bianco P, Pace U, Bianco F, Restivo A, Maretto I, Selvaggi F, Zorcolo L, De Franciscis S, Asteria C, Urso EDL, Cuicchi D, Pellino G, Morpurgo E, La Torre G, Jovine E, Belluco C, La Torre F, Amato A, Chiappa A, Infantino A, Barina A, Spolverato G, Rega D, Kilmartin D, De Salvo GL, Delrio P. Multicentre randomized clinical trial of colonic J pouch or straight stapled colorectal reconstruction after low anterior resection for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2019;106:1147-1155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Harris GJ, Lavery IJ, Fazio VW. Reasons for failure to construct the colonic J-pouch. What can be done to improve the size of the neorectal reservoir should it occur? Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1304-1308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | McDermott FD, Heeney A, Kelly ME, Steele RJ, Carlson GL, Winter DC. Systematic review of preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative risk factors for colorectal anastomotic leaks. Br J Surg. 2015;102:462-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 427] [Cited by in RCA: 589] [Article Influence: 58.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Miyazaki K, Ashida Y, Kihira Y, Mashima K, Yamashita J, Horio T. Transformation of rat liver cell line by Rous sarcoma virus causes loss of cell surface fibronectin, accompanied with secretion of metallo-proteinase that preferentially digests the fibronectin. J Biochem. 1987;102:569-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hallböök O, Johansson K, Sjödahl R. Laser Doppler blood flow measurement in rectal resection for carcinoma--comparison between the straight and colonic J pouch reconstruction. Br J Surg. 1996;83:389-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Montedori A, Cirocchi R, Farinella E, Sciannameo F, Abraha I. Covering ileo- or colostomy in anterior resection for rectal carcinoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010: CD006878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Seow-Choen F, Goh HS. Prospective randomized trial comparing J colonic pouch-anal anastomosis and straight coloanal reconstruction. Br J Surg. 1995;82:608-610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Liang JT, Lai HS, Lee PH, Huang KC. Comparison of functional and surgical outcomes of laparoscopic-assisted colonic J-pouch versus straight reconstruction after total mesorectal excision for lower rectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:1972-1979. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kim NK, Lim DJ, Yun SH, Sohn SK, Min JS. Ultralow anterior resection and coloanal anastomosis for distal rectal cancer: functional and oncological results. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2001;16:234-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Alavi M, Wendel CS, Krouse RS, Temple L, Hornbrook MC, Bulkley JE, McMullen CK, Grant M, Herrinton LJ. Predictors of Bowel Function in Long-term Rectal Cancer Survivors with Anastomosis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:3596-3603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wells CI, Vather R, Chu MJ, Robertson JP, Bissett IP. Anterior resection syndrome--a risk factor analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:350-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |