Published online Feb 27, 2021. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v13.i2.176

Peer-review started: October 19, 2020

First decision: November 23, 2020

Revised: November 30, 2020

Accepted: December 28, 2020

Article in press: December 28, 2020

Published online: February 27, 2021

Processing time: 108 Days and 7 Hours

Whether regional lymphadenectomy (RL) should be routinely performed in patients with T1b gallbladder cancer (GBC) remains a subject of debate.

To investigate whether RL can improve the prognosis of patients with T1b GBC.

We studied a multicenter cohort of patients with T1b GBC who underwent surgery between 2008 and 2016 at 24 hospitals in 13 provinces in China. The log-rank test and Cox proportional hazards model were used to compare the overall survival (OS) of patients who underwent cholecystectomy (Ch) + RL and those who underwent Ch only. To investigate whether combined hepatectomy (Hep) improved OS in T1b patients, we studied patients who underwent Ch + RL to compare the OS of patients who underwent combined Hep and patients who did not.

Of the 121 patients (aged 61.9 ± 10.1 years), 77 (63.6%) underwent Ch + RL, and 44 (36.4%) underwent Ch only. Seven (9.1%) patients in the Ch + RL group had lymph node metastasis. The 5-year OS rate was significantly higher in the Ch + RL group than in the Ch group (76.3% vs 56.8%, P = 0.036). Multivariate analysis showed that Ch + RL was significantly associated with improved OS (hazard ratio: 0.51; 95% confidence interval: 0.26-0.99). Among the 77 patients who underwent Ch + RL, no survival improvement was found in patients who underwent combined Hep (5-year OS rate: 79.5% for combined Hep and 76.1% for no Hep; P = 0.50).

T1b GBC patients who underwent Ch + RL had a better prognosis than those who underwent Ch. Hep + Ch showed no improvement in prognosis in T1b GBC patients. Although recommended by both the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and Chinese Medical Association guidelines, RL was only performed in 63.6% of T1b GBC patients. Routine Ch + RL should be advised in T1b GBC.

Core Tip: Although recommended by both National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines and Chinese Medical Association guidelines, whether regional lymphadenectomy can improve prognosis in patients with T1b gallbladder cancer (GBC) lacks concrete evidence. We performed a multicenter cohort study between 2008 and 2016 at 24 hospitals in 13 provinces in China, representing the largest series of T1b patients in China. We also studied whether combined hepatectomy improved the prognosis. Our data provide necessary evidence for the standardized treatment of GBC.

- Citation: Ren T, Li YS, Dang XY, Li Y, Shao ZY, Bao RF, Shu YJ, Wang XA, Wu WG, Wu XS, Li ML, Cao H, Wang KH, Cai HY, Jin C, Jin HH, Yang B, Jiang XQ, Gu JF, Cui YF, Zhang ZY, Zhu CF, Sun B, Dai CL, Zheng LH, Cao JY, Fei ZW, Liu CJ, Li B, Liu J, Qian YB, Wang Y, Hua YW, Zhang X, Liu C, Lau WY, Liu YB. Prognostic significance of regional lymphadenectomy in T1b gallbladder cancer: Results from 24 hospitals in China. World J Gastrointest Surg 2021; 13(2): 176-186

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v13/i2/176.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v13.i2.176

Gallbladder cancer (GBC) accounts for 80%-95% of biliary tract cancers worldwide, with a median survival of only 6 mo[1]. Surgery is the only potentially curative treatment for GBC[2]. For early-stage T1 GBC, the 5-year survival rate can be as high as 50%-90%[3,4]. However, the appropriate extent of resection for early-stage GBC, especially T1b tumors, is still controversial. Patients are often incidentally found to suffer from GBC after cholecystectomy (Ch), and residual malignancy can be left in up to 37.5% of T1 GBC patients[5]. Additionally, as approximately 15% of T1b GBC patients have lymph node metastasis[6], many clinicians advocate regional lymphadenectomy (RL) of hilar lymph nodes in addition to Ch (Ch + RL). Several studies have reported that Ch + RL improves the prognosis of patients with T1b GBC[6-8]. Moreover, Ch + RL can contribute to better lymph node staging[6]. The guidelines of the Chinese Medical Association (CMA, 2015) and National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN, 2019 version 4) recommend Ch + RL for T1b GBC[2,9].

On the other hand, some studies have shown that Ch is associated with a comparable prognosis as Ch + RL, indicating that RL in the latter procedure is unnecessary[4,10,11]. This study, using a multicenter Chinese cohort of GBC patients, clarified whether Ch + RL improves the prognosis of T1b GBC patients compared to Ch alone and whether hepatectomy (Hep) is necessary in combination with Ch.

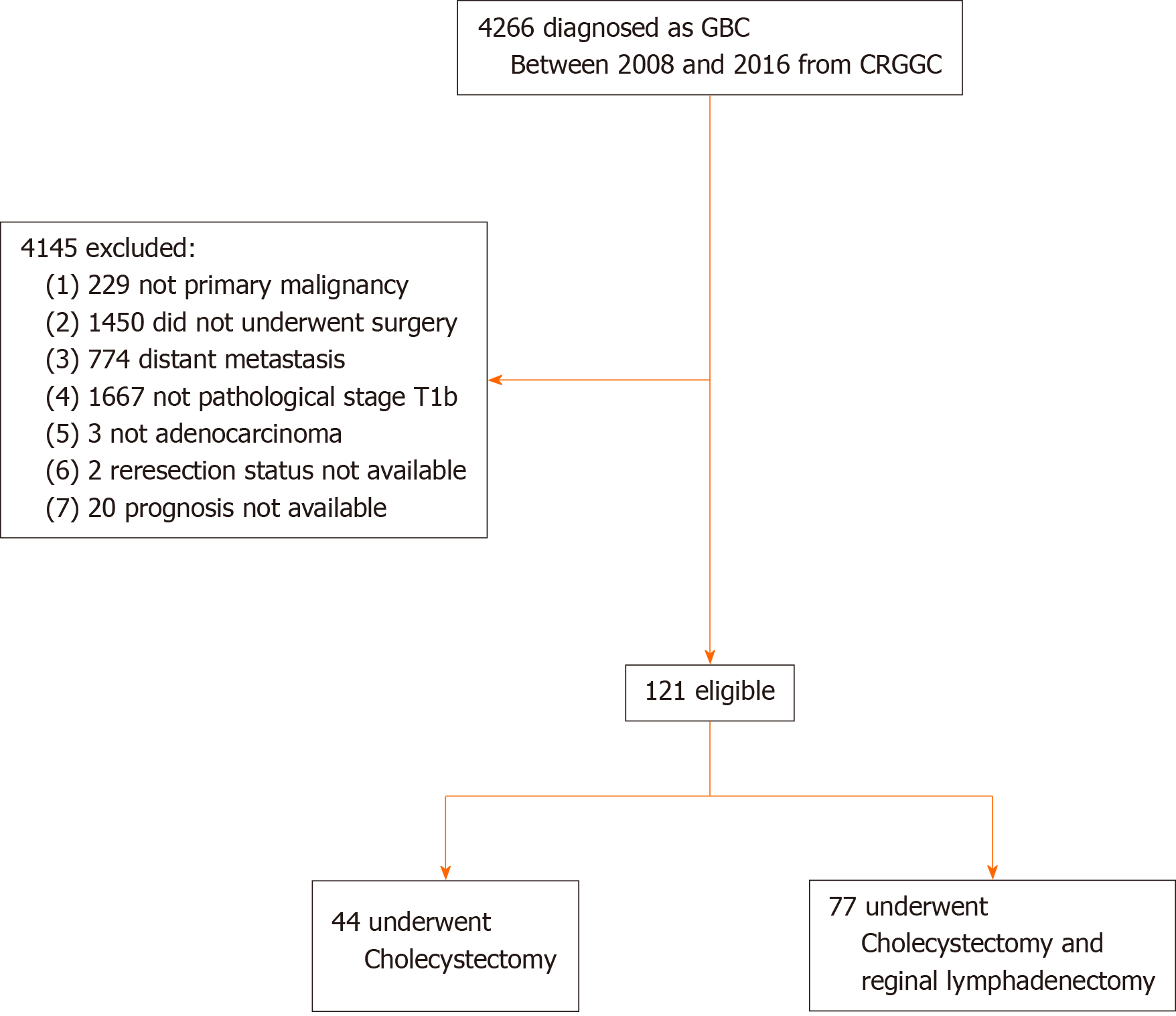

The Chinese Research Group of Gallbladder Cancer (CRGGC) conducted a retrospective multicenter cohort study by collecting the electronic medical records of GBC patients in China to create a study cohort. The protocol of the CRGGC was approved by the Committee for Ethics of Xinhua Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (Ethical Approval SHEC-C-2019-085) and registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04140552). This analysis was performed in April 2020 on data obtained between 2008 and 2016 from 24 hospitals across 13 provinces in China (Supplementary Appendix 1). The inclusion criteria were as follows: Primary adenocarcinoma of the GBC with pathological staging of T1b using the 8th staging guidelines of the American Joint Committee on Cancer; Absence of distant metastasis; treatment by surgical resection of the gallbladder; and For patients who underwent Ch, information on whether a reresection was performed. As patients with GBC are often diagnosed after Ch, they are likely to undergo reresection with or without combined Hep and/or RL to resect any possible residual tumorous disease. Cox regression of the log hazard ratio (HR) on a covariate with a standard deviation of 1.50 based on a sample of 110 observations achieves 80% power at a 0.050 significance level to detect a regression coefficient equal to 0.40. The sample size was adjusted for an anticipated event rate of 0.20. The sample size was calculated using PASS 11.0.7 (NCSS, LLC, Kaysville, UT, United States). As a result, 121 patients were enrolled in this study.

Two surgeons (TR and YSL) independently reviewed the surgical procedures that the patients had undergone based on the cohort. The latest CMA and NCCN guidelines recommend the standard operation for T1b GBC to be Ch + RL, and Ch should be combined with Hep[2,9]. Patients in the Ch group were defined as those who underwent cholecystectomy without RL. Patients in the Ch + RL group included those who underwent a single-stage surgery of Ch plus resection of lymph nodes in the porta hepatis and those who were diagnosed to have incidental GBC after Ch and then underwent repeat surgery for lymph node resection as recommended by the CMA and NCCN guidelines. Patients who underwent Ch + RL may or may not have undergone combined Hep. Patients who underwent Ch + RL and combined Hep were further classified into those who underwent wedge liver resection of the gallbladder bed and segment IVb + V resection. Further biliary tract resection was performed when necessary to achieve R0 resection.

Demographic and clinical data, including pathological and surgical details, were retrieved from the electronic medical records. The hospitals were divided into high- or low-volume centers, depending on whether a center treated more or less than 20 GBC patients annually, based on the rarity of GBC as previously reported[12-14]. As a result, 8 hospitals were classified as high-volume, and 16 as low-volume.

The primary outcome of this study was overall survival (OS), which was defined as the time from the date of the first surgery to the date of death or the date of last contact, whichever came first. Follow-up was routinely performed once every 3-6 mo in the local hospitals.

The patients’ characteristics are reported as the mean ± SD deviation, median (range) or frequency as appropriate. Differences in the baseline characteristics of patients who underwent Ch and those who underwent Ch + RL were compared using the t-test for normally distributed continuous data, the Wilcoxon rank sum test for skewed continuous data, or the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Kaplan-Meier curves and the log-rank test were used to evaluate the survival difference between patients who underwent Ch and those who underwent Ch + RL. Cox proportional hazards models were applied to estimate HRs and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for prognosis after adjusting for age, sex, hospital volume, and resection margin. As lymph node metastasis status could not be determined in patients who underwent Ch, this variable was not included in the models for analysis. The models were tested using different subsets of covariates to assess the robustness of the results. Furthermore, as we classified surgery type according to the surgical reports, some patients who underwent Ch + RL had missing pathological reports on nodal status and were thus excluded from the sensitivity analysis.

Since combined Hep was considered the standard procedure for T1b GBC in the guidelines, this surgical procedure was considered a prognostic factor in this study. Combined Hep was performed in most patients who underwent Ch + RL. To evaluate the prognostic impact of combined Hep + Ch + RL on T1b patients, two analyses were carried out: To adjust combined Hep in the Cox regression, and to determine whether combined Hep improved the prognosis of patients who underwent lymphadenectomy. Kaplan-Meier curves and the log-rank test were used to explore the differences in survival between the dichotomized groups in the subpopulations. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Differences with a two-sided P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The final cohort included 121 patients with primary T1b GBC, of which 44 (36.4%) underwent Ch and 77 (63.6%) Ch + RL (Figure 1). The mean age (± SD) was 61.9 ± 10.1 years, and 91 (75.2%) patients were female. The 5-year OS rate was 70.5%. The median follow-up time was 63.6 mo. The Ch and Ch + RL groups did not differ significantly in age, sex, hospital volume, or poor histological grade. The R0 resection rate was 90.9% in the Ch group and 94.8% in the Ch + RL group (P = 0.46; Table 1). Six patients underwent combined bile duct resection because the tumor location was close to the cystic duct. Of the 40 (33.1%) patients who had incidental GBC, only 15 (37.5%) underwent reoperation for lymphadenectomy and/or combined Hep. Among the 15 patients, 1 had positive nodal disease and one had a positive margin on the cystic duct, but none of the patients showed any residual diseases in the liver bed.

| Characteristic | Ch, n = 44 | Ch + RL, n = 77 | P value |

| Age, mean ± SD in yr | 62.8 ± 11.3 | 61.4 ± 9.4 | 0.48 |

| Female | 34 (77.3) | 57 (74.3) | 0.69 |

| Admitted to high-volume centers1 | 22 (50.0) | 46 (59.7) | 0.30 |

| Nodal metastasis | —3 | ||

| Negative, N0 | 0 (0) | 55 (71.4) | — |

| Positive, N+ | 1 (2.3) | 7 (9.1) | — |

| Undetermined, Nx | 43 (97.7) | 15 (19.5) | — |

| No. of examined nodes, median (range) | 0 (0-1) | 3 (0-14) | —3 |

| Malignancy diagnosed after primary surgery | 25 (56.8) | 15 (19.5) | < 0.001b |

| Hepatectomy | 2 (4.5)2 | 54 (70.1) | < 0.001b |

| Liver wedge resection | 2 (4.5) | 51 (66.2) | — |

| Segment IVb + V resection | 0 (0) | 3 (3.9) | — |

| Bile duct resection | 1 (2.3) | 5 (6.5) | 0.41 |

| Negative resection margin | 40 (90.9) | 73 (94.8) | 0.46 |

| Poor histological grade | 4 (9.1) | 15 (19.5) | 0.19 |

| Microscopic vascular invasion | 0 (0) | 3 (3.9) | 0.55 |

| Perineural invasion | 0 (0) | 1 (1.3) | 1.00 |

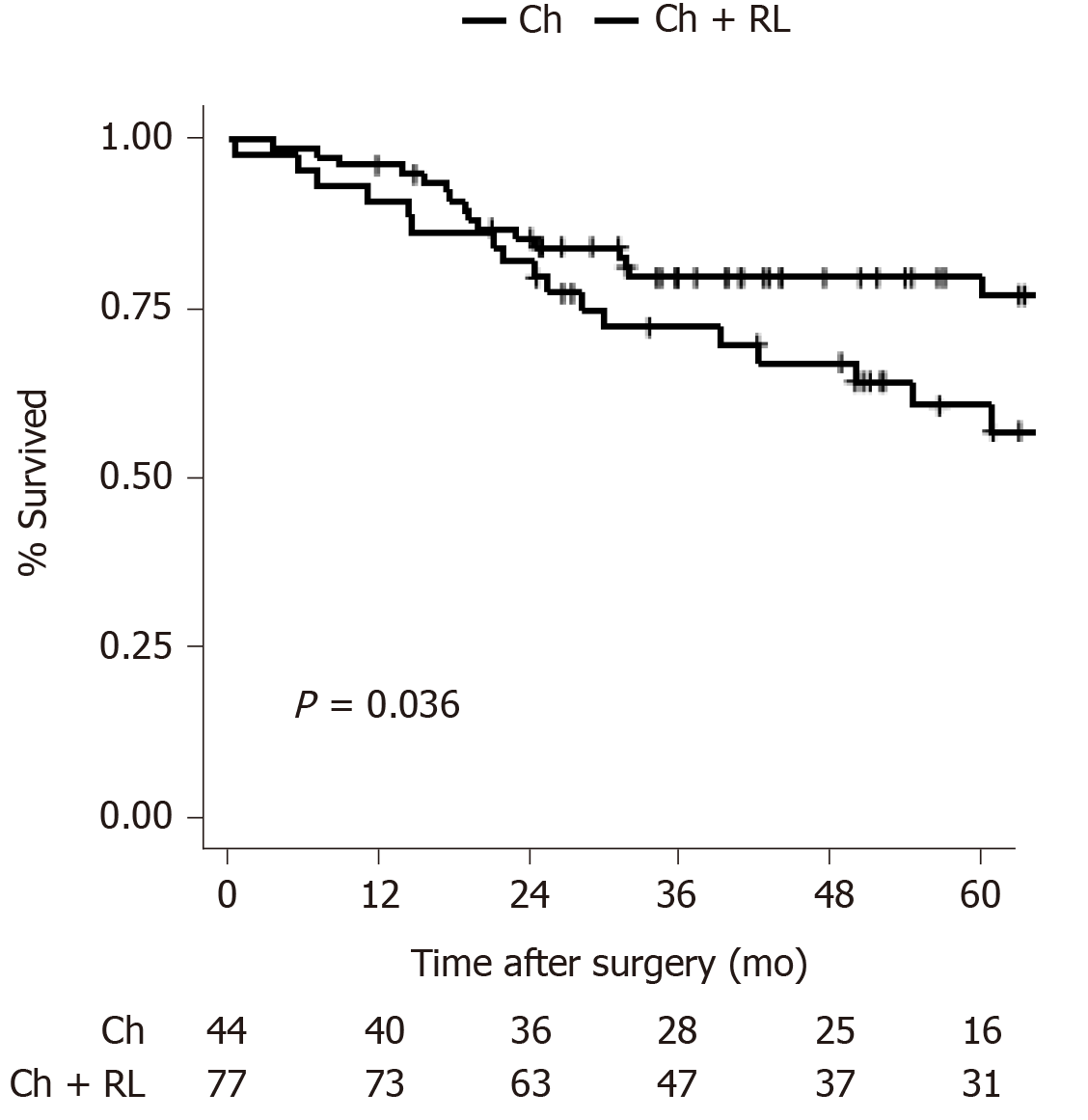

Patients in the Ch group showed a significantly lower 5-year OS rate than those in the Ch + RL group (56.8% vs 76.3%, P = 0.036; Figure 2). In the Cox proportional hazards regression analysis, Ch + RL was a significant protective factor for OS even after adjusting for age, sex, hospital volume, and positive margin (HR: 0.51, 95%CI: 0.26-0.99, P = 0.049; Model 3 in Table 2). To validate this result, a sensitivity analysis was performed excluding patients who underwent Ch + RL and did not have a nodal status (n = 15); and patients who had a positive resection margin (n = 8). Ch + RL was still a significant protective factor for OS (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2).

Patients who underwent Ch had an undetermined nodal status. Patients with this undetermined status were associated with worse OS than those with an absence of positive nodal diseases (Nx vs N0, P = 0.040; Supplementary Table 1). Of the 77 patients who underwent Ch + RL, 7 (9.1%) had positive lymph node metastasis, 55 (71.4%) had negative nodal disease, and 15 (19.5%) had undetermined nodal disease because of missing records in the pathology reports. One patient was found to have a positive lymph node in the post-superior pancreatic region, and this patient underwent extended lymphadenectomy. Among the 7 patients with lymphatic metastasis, only one received chemotherapy. In contrast, most patients who underwent Ch (97.7%) had an undetermined nodal status, as lymphadenectomy was not carried out. However, 4 patients (9.1%) had one or two lymph nodes removed together with the gallbladder, resulting in one patient being diagnosed with positive nodal disease.

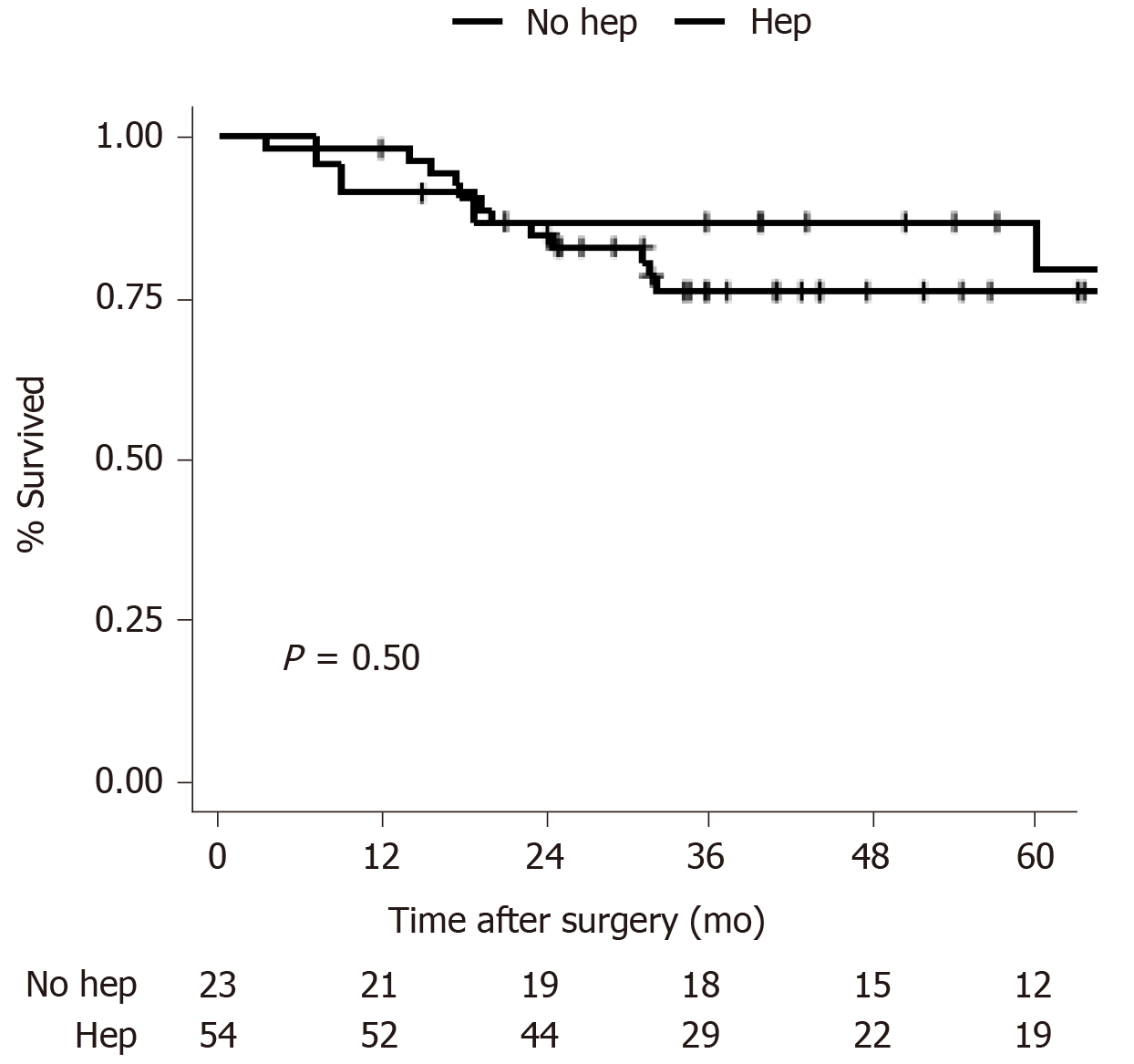

The impact of combined Hep on prognosis was evaluated. Of the 77 patients who underwent Ch + RL, 54 (70.1%) underwent combined Hep + Ch + RL, which included wedge liver resection of the gallbladder bed (n = 51, 94.4%) or segment IVb + V resection (n = 3, 5.6%). Combined Hep was also performed in 2 patients in the Ch group because the tumor was on the liver bed (n = 2). Thus, of the 56 hepatectomies performed in this patient cohort, 54 were performed in the Ch + RL group. Then the prognostic role of combined Hep was evaluated using two sequential methods as follows.

First, combined Hep was adjusted for in the Cox regression (Supplementary Table 3). The variance inflation factor was 2.1 for combined Hep and 2.2 for Ch + RL (compared with 1.1 in Model 3, as shown in Table 2), indicating acceptable collinearity. Ch + RL was still found to be a protective factor for prognosis with marginal significance (HR: 0.37, 95%CI: 0.14-1.00; P = 0.050), a comparable result with Model 3. Second, patients who underwent Ch + RL were examined, and the OS rates of patients who underwent combined Hep and those who did not were compared. No significant difference was found (5-year OS rate: 79.5% for combined Hep and 76.1% for no Hep, P = 0.50; Figure 3). The baseline characteristics of these two subgroups were comparable (Supplementary Table 4).

In this study, the prognostic effect of Ch + RL on T1b GBC patients was evaluated based on a multicenter GBC cohort in China. This study found that patients who underwent Ch + RL had a better prognosis than those who underwent Ch only. This improvement was not associated with combined Hep.

Although Ch + RL is recommended by both the NCCN and CMA guidelines for T1b GBC patients[2,9], this study found that Ch + RL was performed in only 63.6% of T1b GBC patients. Poor compliance has also been reported in the United States, with fewer than 50% of T1b patients undergoing Ch + RL[6]. However, Ch + RL has been shown to improve the elimination rate of residual disease, which can occur in up to 37.5% of patients based on data obtained after reresection[5], with up to 12.5% of patients having lymph node metastases. In our study, approximately 10% of patients in the Ch + RL group showed lymph node metastases, a proportion similar to that reported in the United States[5,6,15]. Thus, for patients who underwent Ch with a lymph node status that cannot be determined, there is a high chance of residual disease in metastatic lymph nodes, highlighting the importance of routine RL in T1b GBC patients.

Although combined Hep has been proposed as a standard procedure for T1b tumors[2], there has been little reported evidence on its beneficial role in patients with T1b GBC. Similarly, the effect of combined Hep on patients with T2 GBC remains controversial, particularly for patients with tumors on the peritoneal side of the gallbladder[16,17]. In assessing the prognostic role of combined Hep in T1b patients in this study, no significant difference in the 5-year OS rates was observed after Ch + RL between patients who underwent combined Hep and those who did not undergo combined Hep. The main purposes of combining Hep with Ch + RL in GBC are: To achieve a negative resection margin, to prevent recurrence due to micrometastases in the gallbladder bed, and to prevent potential invasion of the hepatoduodenal ligament[16]. As T1b tumors are still confined within the muscular layer of the gallbladder, the risk of metastasis to the gallbladder bed should be low. Consistent with the findings of this study, a previous study[5] reported no residual cancer in the liver bed in eight T1 GBC patients who underwent repeat surgery. Additionally, this study did not detect any invasion of the hepatoduodenal ligament in T1b GBC patients. These findings suggested that Ch + RL, without combined Hep, is acceptable when negative resection margins can be guaranteed.

However, Zhang et al[18] found that intraoperative pathology understaged 12 out of 14 consecutive T1b GBC patients, with 11 T2 cases and 1 T3 case confirmed by postoperative pathology. Regarding this risk of understaging, combined Hep should always be considered in the primary operation when the malignancy is diagnosed before or during surgery. On the other hand, for those who were diagnosed after primary surgery, our findings suggested that a reresection of lymphadenectomy could improve both prognosis and accurate staging, while Hep may be less helpful.

This study showed a 5-year OS rate of 70.5% for Chinese patients with T1b GBC, which is higher than those reported from the National Cancer Data Base of the United States (57.5% for cholecystectomy and 48.3% for radical cholecystectomy)[6] but is lower than the rates of 89.0% reported in an international cohort[11] and 90.4% reported in a Korean cohort[4]. These differences could partly be explained by the higher proportions of patients who were positive for lymph node metastasis in our cohort (9.1%) and in the National Cancer Data Base (15%) than in the two other studies (5.8% and 0%). Indeed, a Japanese cohort of T1b patients from 172 hospitals with 15.6% having positive nodal disease reported a comparable 5-year OS rate of 72.5%[19].

Several groups have reported negligible differences in OS between Ch and Ch + RL for T1b patients[4,10,11,20], contrary to the results of this study. Interestingly, three of these four studies reported low rates of positive nodal disease (0%-5.8%), thereby explaining why lymphadenectomy had less of an impact on the elimination of residual disease and on more accurate disease staging. The great variations in the prevalence of positive nodal disease among studies on T1b patients might reflect the heterogeneity of tumor behavior in GBC in different regions.

This study had limitations. First, potential selection bias was inherent in this retrospective study. Second, this study lacked data on the sites of GBC. T2 tumors on the hepatic side have been reported to be associated with a worse prognosis than those on the peritoneal side[14]. Furthermore, the location of the tumor in relation to the liver may influence the efficacy of Hep[17], although this is still controversial[11]. Third, the analysis of combined Hep was performed in a subgroup of T1b patients with a small sample size. This may potentially lead to less statistical power. Further studies on GBC patients with T1b tumors with larger samples are needed. Fourth, as chemotherapy was underused in the study period[12], only 1 patient among 7 with nodal metastasis received chemotherapy, which might improve the prognosis. However, this underusage did not alter our conclusion, as Ch + RL could help find patients with nodal status and improve decision-making in comprehensive treatment.

T1b GBC patients who underwent Ch + RL had a better prognosis than those who underwent Ch. Hep + Ch showed no improvement in prognosis in T1b GBC patients. Only 63.6% of patients with T1b GBC underwent Ch + RL as recommended by guidelines. Routine Ch + RL should be advised for patients with T1b GBC.

Whether regional lymphadenectomy (RL) can improve prognosis in patients with T1b gallbladder cancer (GBC) remains a subject of debate.

To date, controversy persisted on whether RL should be routinely performed in T1b GBC. It’s necessary to provide evidence for the standardized treatment for GBC.

To investigate whether RL can improve the prognosis of patients with T1b GBC.

We studied a multicenter cohort of patients with T1b GBC who underwent surgery between 2008 and 2016 at 24 hospitals in 13 provinces in China. The log-rank test and Cox proportional hazards model were used to compare the overall survival (OS) of patients who underwent cholecystectomy (Ch) + RL and those who underwent Ch only. Furthermore, we studied patients who underwent Ch + RL to compare the OS of patients who underwent combined hepatectomy (Hep) and patients who did not.

Of the 121 patients (aged 61.9 ± 10.1 years), 77 (63.6%) underwent Ch + RL, and 44 (36.4%) underwent Ch only. Seven (9.1%) patients in the Ch + RL group had lymph node metastasis. The 5-year OS rate was significantly higher in the Ch + RL group than in the Ch group (76.3% vs 56.8%, P = 0.036). Multivariate analysis showed that Ch + RL was significantly associated with improved OS (hazard ratio = 0.51; 95% confidence interval: 0.26-0.99). Among the 77 patients who underwent Ch + RL, no survival improvement was found in patients who underwent combined Hep (5-year OS rate: 79.5% for combined Hep and 76.1% for no Hep; P = 0.50).

T1b GBC patients who underwent Ch + RL had a better prognosis than those who underwent Ch. Hep + Ch showed no improvement in prognosis in T1b GBC patients.

Ch + RL should be routinely performed in T1b GBC patients.

We thank Dr. Yang Yang and other colleagues for their significant contributions to the Chinese Research Group on Gallbladder Cancer. A detailed list is provided in Supplementary Appendix 2.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Saglam S S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Hundal R, Shaffer EA. Gallbladder cancer: epidemiology and outcome. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:99-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 490] [Article Influence: 44.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Hepatobiliary Cancers (Version 4. 2019). Accessed February 13, 2020. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/hepatobiliary.pdf. |

| 3. | American Joint Committee on Cancer. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th edition. New York: Springer, 2017: 303-309. |

| 4. | Yoon JH, Lee YJ, Kim SC, Lee JH, Song KB, Hwang JW, Lee JW, Lee DJ, Park KM. What is the better choice for T1b gallbladder cancer: simple versus extended cholecystectomy. World J Surg. 2014;38:3222-3227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Pawlik TM, Gleisner AL, Vigano L, Kooby DA, Bauer TW, Frilling A, Adams RB, Staley CA, Trindade EN, Schulick RD, Choti MA, Capussotti L. Incidence of finding residual disease for incidental gallbladder carcinoma: implications for re-resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1478-86; discussion 1486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Vo E, Curley SA, Chai CY, Massarweh NN, Tran Cao HS. National Failure of Surgical Staging for T1b Gallbladder Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26:604-610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Abramson MA, Pandharipande P, Ruan D, Gold JS, Whang EE. Radical resection for T1b gallbladder cancer: a decision analysis. HPB (Oxford). 2009;11:656-663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Søreide K, Guest RV, Harrison EM, Kendall TJ, Garden OJ, Wigmore SJ. Systematic review of management of incidental gallbladder cancer after cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2019;106:32-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chinese Society of Biliary Surgery. [Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gallbladder carcinoma (2015 edition)]. Linchuang Gandanbing Zazhi. 2015;14:881-890. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Lee SE, Jang JY, Kim SW, Han HS, Kim HJ, Yun SS, Cho BH, Yu HC, Lee WJ, Yoon DS, Choi DW, Choi SH, Hong SC, Lee SM, Kim HJ, Choi IS, Song IS, Park SJ, Jo S; Korean Pancreas Surgery Club. Surgical strategy for T1 gallbladder cancer: a nationwide multicenter survey in South Korea. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:3654-3660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kim HS, Park JW, Kim H, Han Y, Kwon W, Kim SW, Hwang YJ, Kim SG, Kwon HJ, Vinuela E, Járufe N, Roa JC, Han IW, Heo JS, Choi SH, Choi DW, Ahn KS, Kang KJ, Lee W, Jeong CY, Hong SC, Troncoso A, Losada H, Han SS, Park SJ, Yanagimoto H, Endo I, Kubota K, Wakai T, Ajiki T, Adsay NV, Jang JY. Optimal surgical treatment in patients with T1b gallbladder cancer: An international multicenter study. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018;25:533-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ren T, Li YS, Geng YJ, Li ML, Wu XS, Wu WW, Wang XA, Shu YJ, Bao RF, Dong P, Gong W, Gu J, Wang XF, Lu JH, Mu JS, Pan WH, Zhang X, Zhang XL, Fei ZW, Zhang ZY, Wang Y, Cao H, Sun B, Cui YF, Zhu CF, Li B, Zheng LH, Qian YB, Liu J, Dang XY, Liu C, Peng SY, Quan ZW, Liu YB. [Analysis of treatment modalities and prognosis of patients with gallbladder cancer in China from 2010 to 2017]. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2020;58:697-706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Shindoh J, de Aretxabala X, Aloia TA, Roa JC, Roa I, Zimmitti G, Javle M, Conrad C, Maru DM, Aoki T, Vigano L, Ribero D, Kokudo N, Capussotti L, Vauthey JN. Tumor location is a strong predictor of tumor progression and survival in T2 gallbladder cancer: an international multicenter study. Ann Surg. 2015;261:733-739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ito H, Ito K, D'Angelica M, Gonen M, Klimstra D, Allen P, DeMatteo RP, Fong Y, Blumgart LH, Jarnagin WR. Accurate staging for gallbladder cancer: implications for surgical therapy and pathological assessment. Ann Surg. 2011;254:320-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jensen EH, Abraham A, Jarosek S, Habermann EB, Al-Refaie WB, Vickers SA, Virnig BA, Tuttle TM. Lymph node evaluation is associated with improved survival after surgery for early stage gallbladder cancer. Surgery. 2009;146:706-11; discussion 711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cho JK, Lee W, Jang JY, Kim HG, Kim JM, Kwag SJ, Park JH, Kim JY, Park T, Jeong SH, Ju YT, Jung EJ, Lee YJ, Hong SC, Jeong CY. Validation of the oncologic effect of hepatic resection for T2 gallbladder cancer: a retrospective study. World J Surg Oncol. 2019;17:8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lee H, Choi DW, Park JY, Youn S, Kwon W, Heo JS, Choi SH, Jang KT. Surgical Strategy for T2 Gallbladder Cancer According to Tumor Location. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:2779-2786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zhang LF, Hou CS, Guo LM, Tao LY, Ling XF, Wang LX, Xu Z, Xiu DR. [Surgical strategies for treatment of T1b gallbladder cancers diagnosed intraoperatively or postoperatively]. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2017;49:1034-1037. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Ogura Y, Mizumoto R, Isaji S, Kusuda T, Matsuda S, Tabata M. Radical operations for carcinoma of the gallbladder: present status in Japan. World J Surg. 1991;15:337-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wakai T, Shirai Y, Yokoyama N, Nagakura S, Watanabe H, Hatakeyama K. Early gallbladder carcinoma does not warrant radical resection. Br J Surg. 2001;88:675-678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |