Published online Nov 27, 2021. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v13.i11.1484

Peer-review started: April 29, 2021

First decision: June 17, 2021

Revised: June 26, 2021

Accepted: October 31, 2021

Article in press: October 31, 2021

Published online: November 27, 2021

Processing time: 211 Days and 11.4 Hours

Defecation disorders are obscure sequelae that occurs after gastrectomy, and its implication on daily lives of patients have not been sufficiently investigated.

To examine the features of defecation disorders after gastrectomy and to explore its implication on daily lives of patients in a large cohort using the Postgastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Scale (PGSAS)-45.

We conducted a nationwide multi-institutional study using PGSAS-45 to examine the prevalence of postgastrectomy syndrome and its impact on daily lives of patients after various types of gastrectomy. Data were obtained from 2368 eligible patients at 52 institutions in Japan. Of these, 1777 patients who underwent total gastrectomy (TG; n = 393) or distal gastrectomy (DG; n = 1384) were examined. The severity of defecation disorder symptoms, such as diarrhea and constipation, and their correlation with other postgastrectomy symptoms were examined. The importance of defecation disorder symptoms on the living states and quality of life (QOL) of postgastrectomy patients, and those clinical factors that affect the severity of defecation disorder symptoms were evaluated using multiple regression analysis.

Among seven symptom subscales of PGSAS-45, the ranking of diarrhea was 4th in TG and 2nd in DG. The ranking of constipation was 5th in TG and 1st in DG. The symptoms that correlated well with diarrhea were dumping and indigestion in both TG and DG; while those with constipation were abdominal pain and meal-related distress in TG, and were meal-related distress and indigestion in DG. Among five main outcome measures (MOMs) of living status domain, con

Defecation disorder symptoms, particularly constipation, impair the living status and QOL of patients after gastrectomy; therefore, we should pay attention and adequately treat these relatively modest symptoms to improve postoperative QOL.

Core Tip: Symptoms of defecation disorders, such as diarrhea and constipation, are relatively modest and have not received sufficient attention among various postgastrectomy symptoms; therefore, their implication on the daily lives of patients have not been adequately investigated. We evaluated these symptoms using a nationwide multi-institutional collaborative study called the Postgastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Study. The severity of symptoms of defecation disorders were unexpectedly high and both symptoms, particularly constipation, impaired the living status and quality of life (QOL) of patients after gastrectomy; therefore, we should also pay attention and adequately treat these symptoms to improve postoperative QOL.

- Citation: Nakada K, Ikeda M, Takahashi M, Kinami S, Yoshida M, Uenosono Y, Terashima M, Oshio A, Kodera Y. Defecation disorders are crucial sequelae that impairs the quality of life of patients after conventional gastrectomy. World J Gastrointest Surg 2021; 13(11): 1484-1496

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v13/i11/1484.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v13.i11.1484

Various symptoms have been known to appear after gastrectomy and these symptoms affect the daily lives of patients[1-4]. Among these symptoms, dumping[5-8], small stomach syndrome[9-11], and esophageal reflux[12-14] have been noted as characteristic postgastrectomy symptoms and have frequently become clinical problems. However, symptoms of defecation disorders, such as diarrhea and constipation, and especially constipation, are often less conspicuous compared to other characteristic postgastrectomy symptoms, and their features have not yet been adequately assessed. Therefore, in this study, we used data from a large number of patients that were collected in the Postgastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Study (PGSAS), in order to identify the actual distribution and features of defecation disorders, their effects on living status and quality of life (QOL), and clinical factors that strengthen the symptoms of defecation disorders in patients who underwent conventional gastrectomy [total gastrectomy (TG) and distal gastrectomy (DG)].

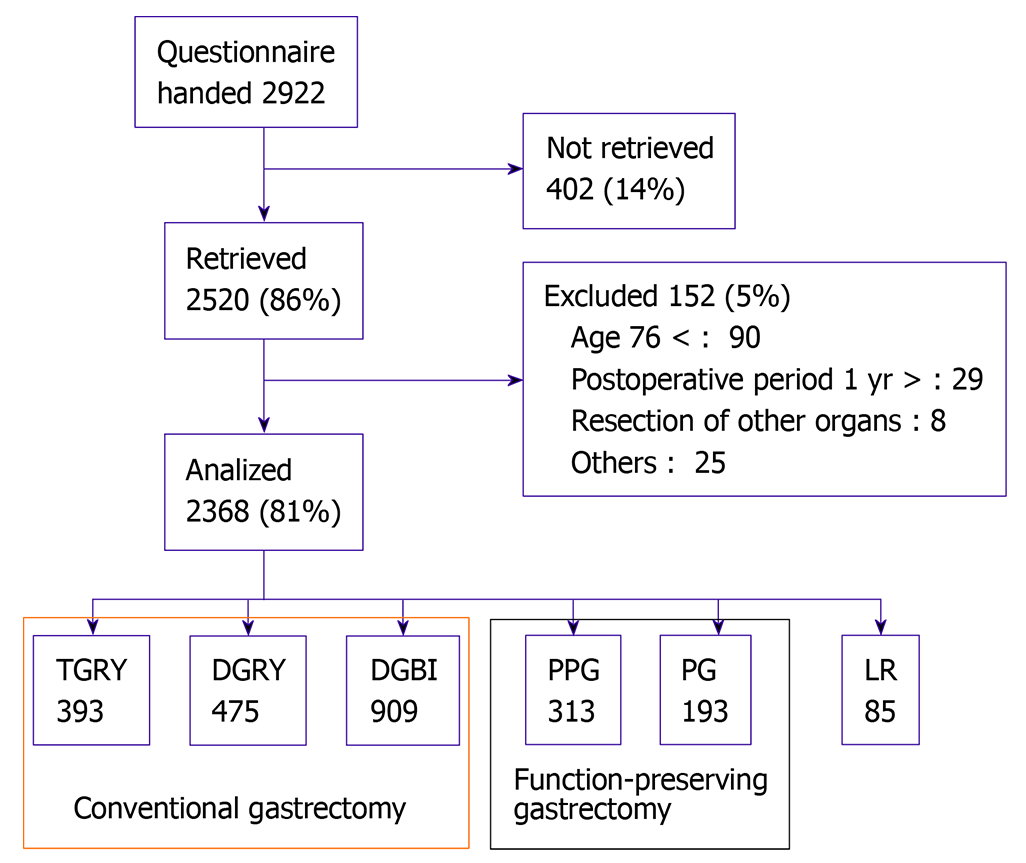

Fifty-two institutions participated in this study. The patient eligibility criteria were: (1) Diagnosis of pathologically-confirmed stage IA or IB gastric cancer; (2) First-time gastrectomy status; (3) Age ≥ 20 and ≤ 75 years; (4) No history of chemotherapy; (5) No indication of recurrence or distant metastasis; (6) Underwent gastrectomy one or more years prior to the date of enrollment; (7) Performance status ≤ 1 on the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group scale; (8) Full capacity to understand and respond to the questionnaire; (9) No history of other diseases or surgeries that might influence the patient’s responses to the questionnaire; (10) Absence of organ failure or mental illness; and (11) Written informed consent. Patients with dual malignancy and those that underwent concomitant resection of other organs (with a co-resection equivalent to a cholecystectomy being the exception) were excluded (Figure 1).

The postgastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Scale (PGSAS)-45[15] is a newly developed, multidimensional QOL questionnaire that is based on the 8-item short form health survey (SF-8)[16] and the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS)[17]. The PGSAS-45 questionnaire consists of a total of 45 questions, with eight items from the SF-8, 15 items from the GSRS, and 22 important clinical items selected by the Japan Postgastrectomy Syndrome Working Party. The PGSAS-45 questionnaire includes 23 items that pertain to postoperative symptoms (items 9–33), including 15 items from the GSRS and eight newly selected items. In addition, 12 questionnaire items that pertain to dietary intake (eight items), work (one item), and level of satisfaction with daily life (three items) were selected. Twenty-three symptom items were consolidated into seven symptom subscales using factor analysis. Afterwards, 19 main outcome measures (MOMs) were refined through the process of consolidation and selection, and were classified into three domains, namely, symptoms, living status, and QOL (Table 1). Details of the PGSAS-45 have been reported previously[15].

| Domain | Main outcome measures |

| Symptoms | Esophageal reflux SS |

| Abdominal pain SS | |

| Meal-related distress SS | |

| Indigestion SS | |

| Diarrhea SS | |

| Constipation SS | |

| Dumping SS | |

| Total symptom score | |

| Living status | Change in BW |

| Ingestion amount of food per meal | |

| Necessity for additional meals | |

| Quality of ingestion SS | |

| Ability for working | |

| QOL | Dissatisfaction with symptoms |

| Dissatisfaction at the meal | |

| Dissatisfaction at working | |

| Dissatisfaction for daily life SS | |

| PCS of SF-8 | |

| MCS of SF-8 |

Continuous sampling from a central registration system was used to enroll participants into this study. The questionnaires were distributed to all eligible patients during their visits to the participating clinics. After completing the questionnaire, patients were instructed to return the forms to the data center. All QOL data from the questionnaires were matched with the data of individual patients that were collected via the case report forms.

This study was registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network’s Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN-CTR; registration number 000002116), and was approved by the local ethics committees at each institution. This study also conformed to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and written informed consent was obtained from all enrolled patients. Of the 2922 patients who were given questionnaires between July 2009 and December 2010, 2520 (86%) responded and 2368 were confirmed to be eligible for the study. Of these, data from 1777 patients who underwent either TG or DG were analyzed in this study.

The statistical methods used to compare patients’ characteristics and severity of symptoms of defecation disorders (i.e., diarrhea and constipation) after TG and DG, included the t-test and chi-square test. Correlations between each symptom of defecation disorders and other postgastrectomy symptoms were calculated in terms of Pearson’s product–moment correlation coefficient (r). The impact of each symptom of defecation disorders on the living status and QOL of patients after gastrectomy were examined using multiple regression analysis. Furthermore, multiple regression analysis was used to explore the effects of independent clinical factors on symptoms of defecation disorders. P value of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

To evaluate effect sizes, Cohen’s d, Pearson correlation coefficient (r), standardization coefficient of regression (β), and coefficient of determination (R2) were used. Interpretation of effect sizes were as follows: using Cohen’s d: ≥ 0.2, small; ≥ 0.5, medium; and ≥ 0.8, large; using Pearson correlation coefficient (r) and standardization coefficient of regression (β): ≥ 0.1, small; ≥ 0.3, medium; and ≥ 0.5, large; while using coefficient of determination (R2): ≥ 0.02, small; ≥ 0.13, medium; and ≥ 0.26, large. Statistical analyses were performed using the JMP version 12.0.1 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States).

Of the 2368 patients whose data were collected in the PGSAS, data from a total of 1777 patients were analyzed, comprising 393 TG cases and 1384 DG cases (Billroth-I method: 909 cases; Roux-en-Y method: 475 cases). Comparisons of patients’ characteristics between those that underwent TG and those that underwent DG showed that those that underwent TG were significantly older, likely to be males, had a shorter postoperative period, and were less likely to undergo laparoscopic approaches as well as preservation of the celiac branch of the vagus nerve (Table 2).

| TG (n = 393) | DG (n = 1384) | P value | |

| Age (yr)1 | 63.4 ± 9.2 | 61.8 ± 9.1 | 0.0022 |

| Gender: | 0.0803 | ||

| Male | 276 (71.0) | 912 (66.2) | |

| Female | 113 (29.0) | 46 5(33.8) | |

| Postoperative period (mo)1 | 35.0 ± 24.6 | 37.6 ± 27.4 | 0.0922 |

| Preoperative BMI (kg/m2)1 | 23.0 ± 3.3 | 22.8 ± 3.0 | 0.1762 |

| Surgical approach: | < 0.0013 | ||

| Laparoscopic | 97 (24.9) | 567 (41.2) | |

| Open | 293 (75.1) | 809 (58.8) | |

| Celiac branch of vagus: | < 0.0013 | ||

| Preserved | 12 (3.1) | 161 (11.9) | |

| Divided | 371 (96.9) | 1196 (88.1) |

Among the seven symptom subscales, the most prominent among patients that underwent TG were meal-related distress (including small stomach syndrome) (1st) and dumping (2nd). The ranking of the severity of symptoms of defecation disorders after TG revealed that diarrhea was the 4th and constipation was the 5th most severe. Meanwhile, the most severe symptoms after DG were constipation (1st) and diarrhea (2nd) (Table 3). Comparisons of the symptoms of defecation disorders between patients that underwent TG and those that had DG showed that diarrhea was significantly more severe after TG; however, no differences were observed between the severity of constipation after TG and after DG (Table 3).

| TG (n = 393) | DG (n = 1384) | |||||

| Mean ± SD | Ranking | Mean ± SD | Ranking | P value | Cohen's d | |

| Esophageal reflux SS | 2.00 ± 1.03 | 6 | 1.64 ± 0.78 | 7 | < 0.001 | 0.43 |

| Abdominal pain SS | 1.77 ± 0.79 | 7 | 1.68 ± 0.77 | 6 | 0.055 | 0.11 |

| Meal-related distress SS | 2.65 ± 1.11 | 1 | 2.07 ± 0.88 | 3 | < 0.001 | 0.62 |

| Indigestion SS | 2.30 ± 0.91 | 3 | 2.01 ± 0.84 | 4 | < 0.001 | 0.34 |

| Diarrhea SS | 2.28 ± 1.19 | 4 | 2.10 ± 1.11 | 2 | 0.007 | 0.16 |

| Constipation SS | 2.09 ± 0.93 | 5 | 2.19 ± 1.03 | 1 | 0.107 | 0.09 |

| Dumping SS | 2.30 ± 1.10 | 2 | 1.96 ± 1.01 | 5 | < 0.001 | 0.32 |

Both diarrhea and constipation had significant positive correlations with all other postgastrectomy symptoms (P < 0.001). However, diarrhea had particularly strong correlations with dumping (1st) and indigestion (2nd) after both TG and DG (Table 4). On the other hand, constipation had particularly strong correlation with abdominal pain (1st) and meal-related distress (2nd) after TG; and meal-related distress (1st) and indigestion (2nd) after DG (Table 4).

| TG (n = 393) | DG (n = 1384) | ||||||

| r | P value | Ranking | r | P value | Ranking | ||

| Diarrhea SS | Esophageal reflux SS | 0.273 | < 0.001 | 6 | 0.260 | < 0.001 | 5 |

| Abdominal pain SS | 0.340 | < 0.001 | 4 | 0.377 | < 0.001 | 3 | |

| Meal-related distress SS | 0.305 | < 0.001 | 5 | 0.358 | < 0.001 | 4 | |

| Indigestion SS | 0.443 | < 0.001 | 2 | 0.420 | < 0.001 | 2 | |

| Constipation SS | 0.341 | < 0.001 | 3 | 0.232 | < 0.001 | 6 | |

| Dumping SS | 0.447 | < 0.001 | 1 | 0.467 | < 0.001 | 1 | |

| Constipation SS | Esophageal reflux SS | 0.392 | < 0.001 | 3 | 0.396 | < 0.001 | 5 |

| Abdominal pain SS | 0.436 | < 0.001 | 1 | 0.444 | < 0.001 | 3 | |

| Meal-related distress SS | 0.402 | < 0.001 | 2 | 0.479 | < 0.001 | 1 | |

| Indigestion SS | 0.365 | < 0.001 | 4 | 0.469 | < 0.001 | 2 | |

| Diarrhea SS | 0.341 | < 0.001 | 6 | 0.232 | < 0.001 | 6 | |

| Dumping SS | 0.350 | < 0.001 | 5 | 0.415 | < 0.001 | 4 | |

Multiple regression analysis was used to investigate the effects of diarrhea and constipation on five MOMs that belong to the living status domain covered in PGSAS-45. No significant effects due to diarrhea were seen after TG; however, constipation had significant adverse effects on the amount of food ingested per meal, necessity for additional meals, quality of ingestion, and ability to work (Table 5).

| TG (n = 393) | DG (n = 1384) | ||||||||||||

| Diarrhea SS | Constipation SS | Diarrhea SS | Constipation SS | ||||||||||

| β | P value | β | P value | R2 | P value | β | P value | β | P value | R2 | P value | ||

| Living status | Change in BW | -0.003 | 0.960 | -0.052 | 0.359 | 0.003 | 0.613 | -0.061 | 0.034 | -0.039 | 0.170 | 0.006 | 0.017 |

| Ingested amount of food per meal | 0.087 | 0.113 | -0.182 | 0.001 | 0.030 | 0.004 | -0.150 | < 0.001 | -0.183 | < 0.001 | 0.069 | < 0.001 | |

| Necessity for additional meals | -0.060 | 0.270 | 0.147 | 0.008 | 0.019 | 0.027 | 0.111 | < 0.001 | 0.182 | < 0.001 | 0.055 | < 0.001 | |

| Quality of ingestion SS | 0.058 | 0.292 | -0.177 | 0.001 | 0.028 | 0.006 | -0.080 | 0.004 | -0.138 | < 0.001 | 0.030 | < 0.001 | |

| Ability for working | -0.071 | 0.189 | 0.275 | < 0.001 | 0.068 | < 0.001 | 0.122 | < 0.001 | 0.260 | < 0.001 | 0.097 | < 0.001 | |

| QOL | Dissatisfaction with symptoms | 0.100 | 0.055 | 0.276 | < 0.001 | 0.105 | < 0.001 | 0.257 | < 0.001 | 0.244 | < 0.001 | 0.155 | < 0.001 |

| Dissatisfaction at the meal | 0.012 | 0.813 | 0.275 | < 0.001 | 0.078 | < 0.001 | 0.266 | < 0.001 | 0.269 | < 0.001 | 0.176 | < 0.001 | |

| Dissatisfaction at working | 0.066 | 0.205 | 0.292 | < 0.001 | 0.102 | < 0.001 | 0.234 | < 0.001 | 0.237 | < 0.001 | 0.137 | < 0.001 | |

| Dissatisfaction for daily life SS | 0.067 | 0.189 | 0.338 | < 0.001 | 0.134 | < 0.001 | 0.297 | < 0.001 | 0.294 | < 0.001 | 0.216 | < 0.001 | |

| PCS of SF-8 | -0.058 | 0.258 | -0.323 | < 0.001 | 0.120 | < 0.001 | -0.140 | < 0.001 | -0.242 | < 0.001 | 0.094 | < 0.001 | |

| MCS of SF-8 | -0.147 | 0.005 | -0.227 | < 0.001 | 0.096 | < 0.001 | -0.214 | < 0.001 | -0.244 | < 0.001 | 0.130 | < 0.001 | |

In patients that underwent DG, both diarrhea and constipation were found to be independent factors that had significant adverse effects on the amount of food ingested per meal, necessity for additional meals, quality of ingestion, and ability to work. However, the effect of constipation was larger in terms of the magnitude of effect size β. Diarrhea had significant adverse effects on weight loss, while constipation had no effect on weight loss (Table 5).

Multiple regression analysis was used to investigate the effect of diarrhea and constipation on six MOMs that belong to the QOL domain covered in PGSAS-45. For TG, diarrhea was found to have significant adverse effects on the mental component summary of SF-8 and had a significant tendency to worsen dissatisfaction with symptoms. Meanwhile, constipation had a significant adverse effect on all six MOMs (Table 5).

In patients that underwent DG, both diarrhea and constipation were factors that worsened all the MOMs in the QOL domain. The effects of diarrhea and constipation were similar in terms of the effect size β; however, the effect of constipation on the physical component summary (PCS) of SF-8 was larger (Table 5).

Multiple regression analysis was used to investigate the background factors that strengthen diarrhea and constipation. Significant factors that worsened diarrhea were young age, division of the celiac branch of vagus, being a male, and undergoing total gastrectomy. Meanwhile, the significant factor that worsened constipation was being a female (Table 6).

| Objective variables | ||||

| Diarrhea SS | Constipation SS | |||

| Explanatory variables | β | P value | β | P value |

| Type of gastrectomy | 0.061 | 0.013 | -0.032 | 0.198 |

| Postoperative period (mo) | -0.038 | 0.123 | -0.010 | 0.697 |

| Age (yr) | -0.102 | < 0.0001 | 0.031 | 0.213 |

| Gender (Male) | 0.062 | 0.010 | -0.073 | 0.003 |

| Approach (laparoscopic) | -0.027 | 0.288 | -0.002 | 0.947 |

| Celiac branch of vagus (preserved) | -0.070 | 0.004 | 0.007 | 0.790 |

| R2 | 0.023 | < 0.0001 | 0.007 | 0.068 |

The various symptoms that appear after gastrectomy and the resultant lower QOL are known clinical problems[1-4]. Among these symptoms, dumping[5-8], small stomach syndrome[9-11], and esophageal reflux[12-14] are well known postgastrectomy symptoms, and have been reported to worsen living status and the QOL[11]. Symptoms of defecation disorders, such as diarrhea and constipation, also occur after gastrectomy[3,18]; however, these symptoms are relatively inconspicuous, particularly constipation. Therefore, their actual distribution, features, and effects on daily life have not been clarified.

Therefore, we used multiple data from the PGSAS to investigate defecation disorders among patients after conventional gastrectomy. Arranging symptoms of defecation disorders in order of severity among the seven symptom subscales that occur after gastrectomy showed that constipation and diarrhea were the most severe in patients that underwent DG. In those that had TG, diarrhea and constipation were ranked relatively low in terms of the severity of symptoms; however, the severity of constipation was almost the same as in those that underwent DG, and diarrhea, was significantly more severe than in those that underwent DG. The correlation results between each symptom of defecation disorders and other symptoms showed that diarrhea had a strong and significant correlation with dumping and indigestion after both TG and DG. Furthermore, constipation showed a strong positive correlation with abdominal pain and meal-related distress after TG; and meal-related distress and indigestion after DG. A multivariate analysis was performed to investigate the impact of defecation disorders on living status and QOL, and this showed that diarrhea had a small effect after TG, whereas constipation had an adverse effect on almost all MOMs. Both diarrhea and constipation had adverse effects on almost all MOMs of living status and QOL after DG, with the effects of constipation being slightly greater. A multivariate analysis that was performed to investigate those clinical factors that strengthened these defecation disorders showed that significant factors that worsened symptoms were being a male, being young, division of the celiac branch of the vagus nerve, and TG for diarrhea; and being a female for constipation. This is the first study to report the actual features, and effects of defecation disorders on daily life, as well as the background factors that enhance defecation disorders.

Various symptoms appear after gastrectomy and are known to interfere with the daily lives of the patients and cause clinical problems[1-4]. Our previous study on which postgastrectomy symptoms had a significant effect on the daily life of patients, showed that among the various postgastrectomy symptoms the daily life of patients after gastrectomy was impaired the most by meal-related distress (including small stomach syndrome) and dumping[11]. Furthermore, esophageal reflux and abdominal pain also had a clear effect on the daily life of patients after gastrectomy[11]. These relatively prominent postgastrectomy symptoms have often been reported and are widely recognized[5-14]. However, symptoms of defecation disorders, such as diarrhea and constipation are also often seen after gastrectomy. Diarrhea has been reported to become worse after vagotomy[9,19] and gastrectomy[3,19], and it is a relatively well recognized symptom. Meanwhile, constipation has not received adequate attention and has not been sufficiently investigated.

The relationship between the type of surgical procedure and the ranking of the severity of defecation disorder symptoms showed that defecation disorders were most severe after DG, and constipation ranked first, and diarrhea ranked second. The most severe symptoms after TG were meal-related distress and dumping, which were the first and second, respectively. Symptoms of defecation disorders were ranked relatively low after TG, as diarrhea and constipation ranked fourth and fifth, respectively, among the seven symptoms. However, comparison of the symptom severity in patients that underwent DG showed that constipation was almost identical after either DG or TG, and diarrhea was significantly more severe after TG than after DG. In other words, the results showed that the symptoms of defecation disorders after TG were not necessarily mild compared to those that occur after DG, and that they were only less prominent due to the presence of other more severe symptoms. Therefore, paying attention to the occurrence of symptoms of defecation disorders and taking appropriate measures are also important after TG.

Correlation analyses between each symptom of defecation disorders and other postgastrectomy symptoms showed that diarrhea had a strong correlation with dumping (1st) and indigestion (2nd) for both TG and DG. Accelerated gastric emptying has been observed after gastrectomy[20,21], and the increased dumping and diarrhea that occurs is considered consistent with the pathogenesis of these symptoms[8,22,23]. Previous studies has revealed that there was a significant relationship between accelerated gastric emptying and diarrhea as well as dumping after gastrectomy[24,25]. The results of their study may, in part, explain the results of the present study.

Furthermore, constipation was strongly correlated with abdominal pain (1st) and meal-related distress (2nd) after TG; and meal-related distress (1st) and indigestion (2nd) after DG. Postprandial distress syndrome of functional dyspepsia, abdominal pain, abdominal distension and indigestion are known to be often accompanied with constipation[26,27]. Similarly, these symptoms were shown to be commonly accompanied with postgastrectomy constipation.

Symptoms of defecation disorders, such as diarrhea and constipation have been reported to decrease the QOL of patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)[28,29]. Our results showed that symptoms of defecation disorders were factors that also had significantly adverse effects on living status and QOL in postgastrectomy patients. The magnitude of the effects of symptoms of defecation disorders on QOL after gastrectomy was significantly greater with regards to constipation than diarrhea after TG. Meanwhile, both constipation and diarrhea had significant effects on living status and QOL after DG, but constipation had slightly larger effects than diarrhea. Symptoms of defecation disorders, particularly constipation, are not prominent when compared to other characteristic postgastrectomy symptoms and are not often noticed. However, as our results showed that their effects on daily life were more significant than expected; hence, it is thought that taking appropriate measures to relieve these symptoms without overlooking their appearance would lead to the improved daily lives of patients.

Results of the multivariate analysis of factors that strengthen the symptoms of postgastrectomy defecation disorders showed that those significant independent factors in descending order of their effect on diarrhea were young age, division of the celiac branch of the vagus nerve, being male, and undergoing TG; and being female was a significant independent factor for constipation. The relationship between sex, age, and defecation disorders has been reported and diarrhea was found to be more significant in males and younger patients, while constipation was found to be more significant in females and older patients[30-32]. Regarding IBS, which is a functional gastrointestinal disease, it has also been reported that the diarrhea-type is more common among men, and the constipation-type is more common among women[33]. Reports on the relationship between surgical procedures and defecation disorders have shown that vagotomy worsens diarrhea[9,19], and diarrhea became more severe after TG compared to other surgical procedures[34,35]. The results of our study were consistent with those of previous reports, therefore, these clinical factors should be recognized as valid factors that worsen postgastrectomy defecation disorders.

Factors that cause diarrhea after gastrectomy were thought to include rapid influx of food into the small intestine due to accelerated gastric emptying[23], accelerated intestinal peristalsis due to increased load on the small intestine[36], changes in intestinal flora due to low or no acidity[18,37], decreased pancreatic exocrine function[38], and discrepancies in the timing of the mixing of food and duodenal fluid such as pancreatic juice and bile (postcibal pancreatico-biliary asynchrony)[39]. Meanwhile, factors that cause constipation after gastrectomy are thought to include reduced gastro-colic reflex due to vagotomy[40], decreased food intake (especially fiber, water, fat)[4,41], decreased abdominal pressure due to decreased skeletal muscle mass (especially abdominal muscles)[42], lack of exercise[43], and changes in the intestinal flora and intestinal environment[18,44].

Gastrectomy induces the above-mentioned changes that can induce defecation disorders; hence, attention must also be paid to the occurrence of defecation disorders after gastrectomy.

This study has several limitations. First, this is a retrospective study; there is a possibility that unknown clinical factors other than gastrectomy may have affected the results. Second, this is a cross-sectional study at a single-time point, and there are variations in the postoperative period. However, this effect is considered minimal even if present because it has been reported that postgastrectomy QOL decreased the most in the first month postoperatively and stabilized after approximately 6 mo to a year[45], and this study used stable patients over one year postoperatively as subjects. Despite these limitations, we were able to obtain clinically useful information on postgastrectomy defecation disorders by investigating a rather large number of cases from various perspectives using the PGSAS-45 questionnaire, which is specialized for the evaluation of postgastrectomy.

In this study, we were able to clarify the features of postgastrectomy defecation disorders and its effects on daily life, although they have not been regarded as significant problems to date. Attention has often been given to characteristic postgastrectomy symptoms, such as dumping and small stomach syndrome. However, since inconspicuous symptoms of defecation disorders (especially constipation) also affect the daily lives of post-operative patients to some extent, paying attention to the occurrence of these symptoms as well and implementing the appropriate guidance and treatment were considered necessary in order to improve the QOL of postgastrectomy patients.

Various symptoms that can interfere with the postoperative quality of life (QOL) of patients occur after gastrectomy. The symptoms of defecation disorders, particularly constipation, are relatively modest compared to other postgastrectomy symptoms; therefore, their features and implications on the daily lives of patients have not been adequately investigated.

Several studies have investigated the effect of characteristic postgastrectomy symptoms, such as dumping, small stomach syndrome, and esophageal reflux on the daily lives of patients. However, the implications of symptoms of defecation disorders on patient’s QOL postgastrectomy are poorly understood.

The central goal of this research was to reveal the features of symptoms of defecation disorders and their effects on the daily lives of patients in a large population of gastrectomized patients using the Postgastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Scale (PGSAS)-45, and analyze the data derived using multivariate analysis.

The 1777 patients who underwent total gastrectomy (TG; n = 393) or distal gastrectomy (DG; n = 1384) were enrolled in this study. The severity of defecation disorder symptoms, such as diarrhea and constipation, and their correlation with other postgastrectomy symptoms were examined. The importance of defecation disorder symptoms on the living states and QOL of postgastrectomy patients, and those clinical factors that affect the severity of defecation disorder symptoms were evaluated using multiple regression analysis.

The ranking of defecation disorder symptoms were unexpectedly high in DG among seven symptom subscales of PGSAS-45. There were significant correlation between defecation disorder symptoms and other postgastrectomy symptoms. The defecation disorder symptom, constipation in particular, impaired postgastrectomy living status and QOL. Male sex, younger age, division of the celiac branch of vagus nerve, and TG, independently worsened diarrhea, while female sex worsened constipation.

The severity of symptoms of defecation disorders were unexpectedly high and both symptoms, particularly constipation, impaired the living status and QOL of patients after gastrectomy.

Paying attention to the symptoms of defecation disorders as well as characteristic postgastrectomy symptoms and treating these symptoms adequately may improve the QOL of patients after gastrectomy.

This study was completed with the help of 52 institutions in Japan. The authors thank all the physicians that participated in this study and all the patients whose cooperation made this study possible.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: The Jikei University School of Medicine, The Jikei University School of Medicine; Japan Surgical Society, 0248522; The Japanese Society of Gastroenterological Surgery, G0136608; The Japanese Society of Gastroenterology, 16095; The Japanese Gastroenterologial Association, 013307.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Pinheiro RN S-Editor: Liu M L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu M

| 1. | Bolton JS, Conway WC 2nd. Postgastrectomy syndromes. Surg Clin North Am. 2011;91:1105-1122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Carvajal SH, Mulvihill SJ. Postgastrectomy syndromes: Dumping and diarrhea. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1994;23:261-279. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Scarpellini E, Arts J, Karamanolis G, Laurenius A, Siquini W, Suzuki H, Ukleja A, Van Beek A, Vanuytsel T, Bor S, Ceppa E, Di Lorenzo C, Emous M, Hammer H, Hellström P, Laville M, Lundell L, Masclee A, Ritz P, Tack J. International consensus on the diagnosis and management of dumping syndrome. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:448-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 29.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tanizawa Y, Tanabe K, Kawahira H, Fujita J, Takiguchi N, Takahashi M, Ito Y, Mitsumori N, Namikawa T, Oshio A, Nakada K; Japan Postgastrectomy Syndrome Working Party. Specific Features of Dumping Syndrome after Various Types of Gastrectomy as Assessed by a Newly Developed Integrated Questionnaire, the PGSAS-45. Dig Surg. 2016;33:94-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Mine S, Sano T, Tsutsumi K, Murakami Y, Ehara K, Saka M, Hara K, Fukagawa T, Udagawa H, Katai H. Large-scale investigation into dumping syndrome after gastrectomy for gastric cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:628-636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tack J, Arts J, Caenepeel P, De Wulf D, Bisschops R. Pathophysiology, diagnosis and management of postoperative dumping syndrome. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:583-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Eagon JC, Miedema BW, Kelly KA. Postgastrectomy syndromes. Surg Clin North Am. 1992;72:445-465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Iivonen MK, Mattila JJ, Nordback IH, Matikainen MJ. Long-term follow-up of patients with jejunal pouch reconstruction after total gastrectomy. A randomized prospective study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:679-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nakada K, Takahashi M, Ikeda M, Kinami S, Yoshida M, Uenosono Y, Kawashima Y, Nakao S, Oshio A, Suzukamo Y, Terashima M, Kodera Y. Factors affecting the quality of life of patients after gastrectomy as assessed using the newly developed PGSAS-45 scale: A nationwide multi-institutional study. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:8978-8990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Im MH, Kim JW, Kim WS, Kim JH, Youn YH, Park H, Choi SH. The impact of esophageal reflux-induced symptoms on quality of life after gastrectomy in patients with gastric cancer. J Gastric Cancer. 2014;14:15-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ichikawa D, Komatsu S, Okamoto K, Shiozaki A, Fujiwara H, Otsuji E. Evaluation of symptoms related to reflux esophagitis in patients with esophagogastrostomy after proximal gastrectomy. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2013;398:697-701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Nunobe S, Okaro A, Sasako M, Saka M, Fukagawa T, Katai H, Sano T. Billroth 1 vs Roux-en-Y reconstructions: a quality-of-life survey at 5 years. Int J Clin Oncol. 2007;12:433-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Nakada K, Ikeda M, Takahashi M, Kinami S, Yoshida M, Uenosono Y, Kawashima Y, Oshio A, Suzukamo Y, Terashima M, Kodera Y. Characteristics and clinical relevance of postgastrectomy syndrome assessment scale (PGSAS)-45: newly developed integrated questionnaires for assessment of living status and quality of life in postgastrectomy patients. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:147-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Turner-Bowker DM, Bayliss MS, Ware JE Jr, Kosinski M. Usefulness of the SF-8 Health Survey for comparing the impact of migraine and other conditions. Qual Life Res. 2003;12:1003-1012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 254] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Revicki DA, Wood M, Wiklund I, Crawley J. Reliability and validity of the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Qual Life Res. 1998;7:75-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 369] [Cited by in RCA: 449] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Aoki T, Yamaji I, Hisamoto T, Sato M, Matsuda T. Irregular bowel movement in gastrectomized subjects: bowel habits, stool characteristics, fecal flora, and metabolites. Gastric Cancer. 2012;15:396-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Morris SJ, Rogers AI. Diarrhea after gastrectomy and vagotomy. Postgrad Med. 1979;65:219-222, 225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | MacGregor I, Parent J, Meyer JH. Gastric emptying of liquid meals and pancreatic and biliary secretion after subtotal gastrectomy or truncal vagotomy and pyloroplasty in man. Gastroenterology. 1977;72:195-205. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Kawamura M, Nakada K, Konishi H, Iwasaki T, Murakami K, Mitsumori N, Hanyu N, Omura N, Yanaga K. Assessment of motor function of the remnant stomach by ¹³C breath test with special reference to gastric local resection. World J Surg. 2014;38:2898-2903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Berg P, McCallum R. Dumping Syndrome: A Review of the Current Concepts of Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:11-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Charles F, Phillips SF, Camilleri M, Thomforde GM. Rapid gastric emptying in patients with functional diarrhea. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72:323-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Konishi H, Nakada K, Kawamura M, Iwasaki T, Murakami K, Mitsumori N, Yanaga K. Impaired Gastrointestinal Function Affects Symptoms and Alimentary Status in Patients After Gastrectomy. World J Surg. 2016;40:2713-2718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ralphs DN, Thomson JP, Haynes S, Lawson-Smith C, Hobsley M, Le Quesne LP. The relationship between the rate of gastric emptying and the dumping syndrome. Br J Surg. 1978;65:637-641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Choung RS, Locke GR 3rd, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Talley NJ. Cumulative incidence of chronic constipation: a population-based study 1988-2003. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1521-1528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Matsuzaki J, Suzuki H, Asakura K, Fukushima Y, Inadomi JM, Takebayashi T, Hibi T. Classification of functional dyspepsia based on concomitant bowel symptoms. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:325-e164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Mönnikes H. Quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45 Suppl:S98-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sánchez Cuén JA, Irineo Cabrales AB, Bernal Magaña G, Peraza Garay FJ. Health-related quality of life in adults with irritable bowel syndrome in a Mexican specialist hospital. A cross-sectional study. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2017;109:265-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Talley NJ, Jones M, Nuyts G, Dubois D. Risk factors for chronic constipation based on a general practice sample. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1107-1111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Chang L, Toner BB, Fukudo S, Guthrie E, Locke GR, Norton NJ, Sperber AD. Gender, age, society, culture, and the patient's perspective in the functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1435-1446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 256] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Herman J, Pokkunuri V, Braham L, Pimentel M. Gender distribution in irritable bowel syndrome is proportional to the severity of constipation relative to diarrhea. Gend Med. 2010;7:240-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Choghakhori R, Abbasnezhad A, Amani R, Alipour M. Sex-Related Differences in Clinical Symptoms, Quality of Life, and Biochemical Factors in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:1550-1560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Takiguchi N, Takahashi M, Ikeda M, Inagawa S, Ueda S, Nobuoka T, Ota M, Iwasaki Y, Uchida N, Kodera Y, Nakada K. Long-term quality-of-life comparison of total gastrectomy and proximal gastrectomy by postgastrectomy syndrome assessment scale (PGSAS-45): a nationwide multi-institutional study. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:407-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Takahashi M, Terashima M, Kawahira H, Nagai E, Uenosono Y, Kinami S, Nagata Y, Yoshida M, Aoyagi K, Kodera Y, Nakada K. Quality of life after total vs distal gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y reconstruction: Use of the Postgastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Scale-45. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:2068-2076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Bond JH, Levitt MD. Use of breath hydrogen (H2) to quantitate small bowel transit time following partial gastrectomy. J Lab Clin Med. 1977;90:30-36. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Swidsinski A, Loening-Baucke V, Verstraelen H, Osowska S, Doerffel Y. Biostructure of fecal microbiota in healthy subjects and patients with chronic idiopathic diarrhea. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:568-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Straatman J, Wiegel J, van der Wielen N, Jansma EP, Cuesta MA, van der Peet DL. Systematic Review of Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency after Gastrectomy for Cancer. Dig Surg. 2017;34:364-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Sato T, Konishi K, Yabushita K, Kimura H, Maeda K, Tsuji M, Kinuya K, Nakajima K. Long-term postoperative functional evaluation of pylorus preservation in Imanaga pancreatoduodenectomy. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:1907-1912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Malone JC, Thavamani A. Physiology, Gastrocolic Reflex. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2021. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Thompson J. Understanding the role of diet in adult constipation. Nurs Stand. 2020;35:39-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Asaoka D, Takeda T, Inami Y, Abe D, Shimada Y, Matsumoto K, Ueyama H, Komori H, Akazawa Y, Osada T, Hojo M, Nagahara A. Association between the severity of constipation and sarcopenia in elderly adults: A single-center university hospital-based, cross-sectional study. Biomed Rep. 2021;14:2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Ghoshal UC. Review of pathogenesis and management of constipation. Trop Gastroenterol. 2007;28:91-95. [PubMed] |

| 44. | Zhao Y, Yu YB. Intestinal microbiota and chronic constipation. Springerplus. 2016;5:1130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Kobayashi D, Kodera Y, Fujiwara M, Koike M, Nakayama G, Nakao A. Assessment of quality of life after gastrectomy using EORTC QLQ-C30 and STO22. World J Surg. 2011;35:357-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |