Published online Jan 27, 2021. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v13.i1.30

Peer-review started: August 3, 2020

First decision: September 17, 2020

Revised: September 22, 2020

Accepted: December 2, 2020

Article in press: December 2, 2020

Published online: January 27, 2021

Processing time: 164 Days and 0.8 Hours

The management of cystic dystrophy of the duodenal wall (CDDW), or groove pancreatitis (GP), remains controversial. Although pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) is considered the most suitable operation for CDDW, pancreas-preserving duodenal resection (PPDR) has also been suggested as an alternative for the pure form of GP (isolated CDDW). There are no studies comparing PD and PPDR for this disease.

To compare the safety, efficacy, and short- and long-term results of PD and PPDR in patients with CDDW.

A retrospective analysis of the clinical, radiologic, pathologic, and intra- and postoperative data of 84 patients with CDDW (2004-2020) and a comparison of the safety and efficacy of PD and PPDR.

Symptoms included abdominal pain (100%), weight loss (76%), vomiting (30%) and jaundice (18%) and data from computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and endoUS led to the correct preoperative diagnosis in 98.8% of cases. Twelve patients were treated conservatively with pancreaticoenterostomy (n = 8), duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection (n = 6), PD (n = 44) and PPDR (n = 15) without mortality. Weight gain was significantly higher after PD and PPDR and complete pain control was achieved significantly more often after PPDR (93%) and PD (84%) compared to the other treatment modalities (18%). New onset diabetes mellitus and severe exocrine insufficiency occurred after PD (31% and 14%), but not after PPDR.

PPDR has similar safety and better efficacy than PD in patients with CDDW and may be the optimal procedure for the isolated form of CDDW. The pure form of GP is a duodenal disease and PD may be an overtreatment for this disease. Early detection of CDDW provides an opportunity for pancreas-preserving surgery.

Core Tip: This is a retrospective study that compared the safety, efficacy, short- and long-term results of pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) and pancreas-preserving duodenal resections (PPDR) in patients with groove pancreatitis (GP). Although PD is a conventional option for GP management, PPDR has been suggested as a treatment alternative for the pure form of GP in the early stage of this disease. Evaluation of these two treatment modalities has shown that PPDR for the pure form of GP is similar in terms of safety and better in efficacy compared to PD performed for GP. The key aim of this study is to demonstrate that PPDR may be the treatment of choice for the pure form of GP, which is a disease of the duodenum; early detection of GP makes preservation of the pancreas possible, and prolonged conservative treatment in early GP may lead to the development of segmental and diffuse pancreatitis, which may deprive patients of the pancreas-preserving option; PD is an overtreatment for the pure form of GP, since it involves resection of undamaged pancreas, which means that PPDR may be an alternative treatment procedure for GP.

- Citation: Egorov V, Petrov R, Schegolev A, Dubova E, Vankovich A, Kondratyev E, Dobriakov A, Kalinin D, Schvetz N, Poputchikova E. Pancreas-preserving duodenal resections vs pancreatoduodenectomy for groove pancreatitis. Should we revisit treatment algorithm for groove pancreatitis? World J Gastrointest Surg 2021; 13(1): 30-49

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v13/i1/30.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v13.i1.30

Cystic dystrophy of the duodenal wall (CDDW) is a relatively rare form of chronic pancreatitis (CP). It is mainly observed in middle-aged men and manifests with abdominal pain, weight loss, and occasionally vomiting and jaundice[1-7]. In the literature, it has also been referred to as groove pancreatitis (GP)[8-11], periampullary duodenal wall cyst[12], adenomyoma[13,14], paraduodenal pancreatitis (PP)[15-17], and pancreatic hamartoma of the duodenum[18-20]. All these terms refer to the same histology, each one putting the emphasis on one of its different manifestations: Fibrotic inflammatory changes of the duodenal wall, spread of fibrosis to the groove area (thin area between the pancreas, common bile duct and duodenum) and common bile duct opening, duodenum wall thickening accompanied by intramural cyst formation, Brunner’s gland hyperplasia and fragments of ectopic pancreatic tissue with myoid cells infiltrating the duodenal wall[1,2,8,9,15].

This entity was first described as “cystic dystrophy” of the duodenal wall in 1970 by Potet et al[1]. Stolte et al[8] in 1982 and Becker et al[9] in 1991 used the term GP, dividing it into “pure” and “segmental” forms. The “pure” form of the disease (which correlates to the isolated form of CDDW in the original description[1]) refers to the condition where only cicatricial changes occur in the duodenum and area of the groove between the duodenum and the pancreas, while the pancreatic parenchyma remains intact. The “segmental” form of the disease is characterized by both the fibrotic changes of the groove, as well as signs of CP (fibrosis, pancreatic calculi, cysts, and changes of the duct of Wirsung) in the head of the pancreas or in the whole gland. In 2004, Adsay et al[15] introduced the notion of “paraduodenal pancreatitis,” also discriminating two types of the disease: “Pure” and “Segmental”[17]. When considering groove, or PP, some authors also divide it into solid and cystic forms, depending on whether only fibro-inflammatory thickening of the medial duodenal wall is present or whether this thickening is accompanied by cystic transformation[15-17]. Therapeutic approaches to treatment remain controversial, as well as the opinions on its primary cause, but today pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) is considered preferable and even a first-line treatment option for CDDW[4,6,10,11,17,21-24]. Pancreas-preserving duodenal resection (PPDR) was introduced into practice in 2009[25], and the objectives of this study were a comparison of the safety and efficacy of PD and PPDR in patients with CDDW.

A retrospective analysis of pre- and post-treatment data of 84 consecutive patients with CDDW treated by our group between February 2004 and April 2020 was performed. Patients with the so-called “solid type” of groove or PP were not included, as thickening (i.e., inflammatory infiltration) of the medial duodenal wall in such patients may be the consequence, rather than the cause of chronic or acute inflammation of the pancreas. Intraoperative and short- and long-term postoperative data of the patients who underwent PD (n = 44) and PPDR (n = 15) were compared.

Patient information included demographic data, medical history, history of alcohol consumption and smoking and information on pancreatic endocrine and exocrine insufficiency. All blood tests and imaging studies were performed according to standard protocols.

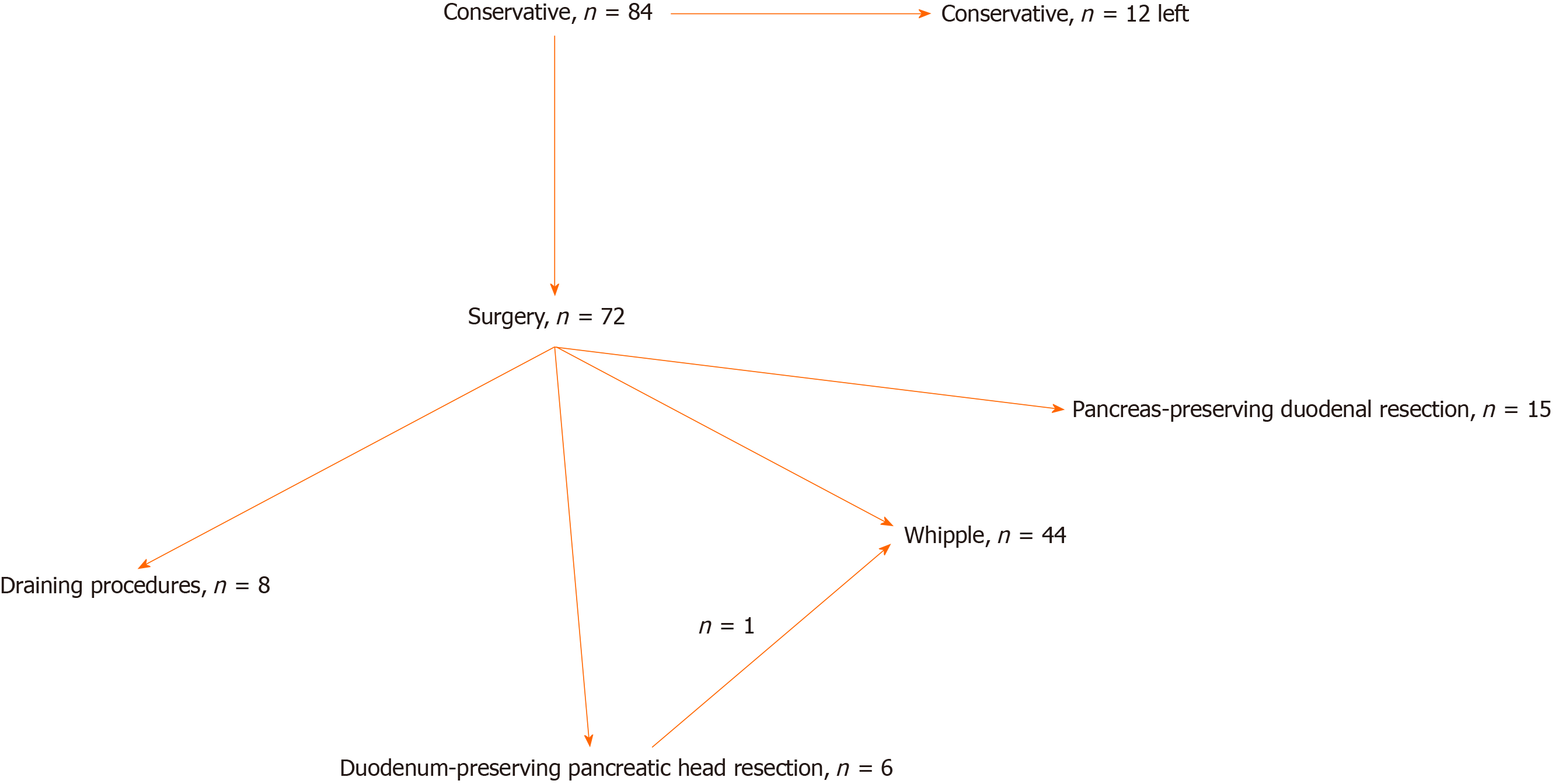

All the cases were discussed at multidisciplinary meetings, which included experts in gastroenterology, pancreas surgery, radiology, oncology and endocrinology. Primary operative procedures were all elective. In all patients, initial treatment was conservative, which included smoking and alcohol cessation, analgesics, proton pump inhibitors, short- or long-acting somatostatin analogues, nutritional support and pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT), along with endoscopic procedures, including endoscopic ultrasonography, stenting, fine-needle aspiration and/or core-needle biopsy[4,6,10,16,17]. Indications for surgical intervention were conservative and/or endoscopic treatment failure manifested by persistence of pain, duodenal obstruction, jaundice and (in one case) suspected tumor[4,6,16,17]. The choice of the type of surgery changed with time, as our insight into the nature of the disease evolved. Patient flow is shown in Figure 1.

The procedures performed have been described in detail in our previous publications[6,25] and elsewhere. These included internal drainage of the main pancreatic duct[7,16,17], duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection (DPPHR)[26,27], pylorus-preserving (ppPD) and classical PD (Whipple procedure), Nakao procedure (PD modification)[24], and PPDR[6,25].

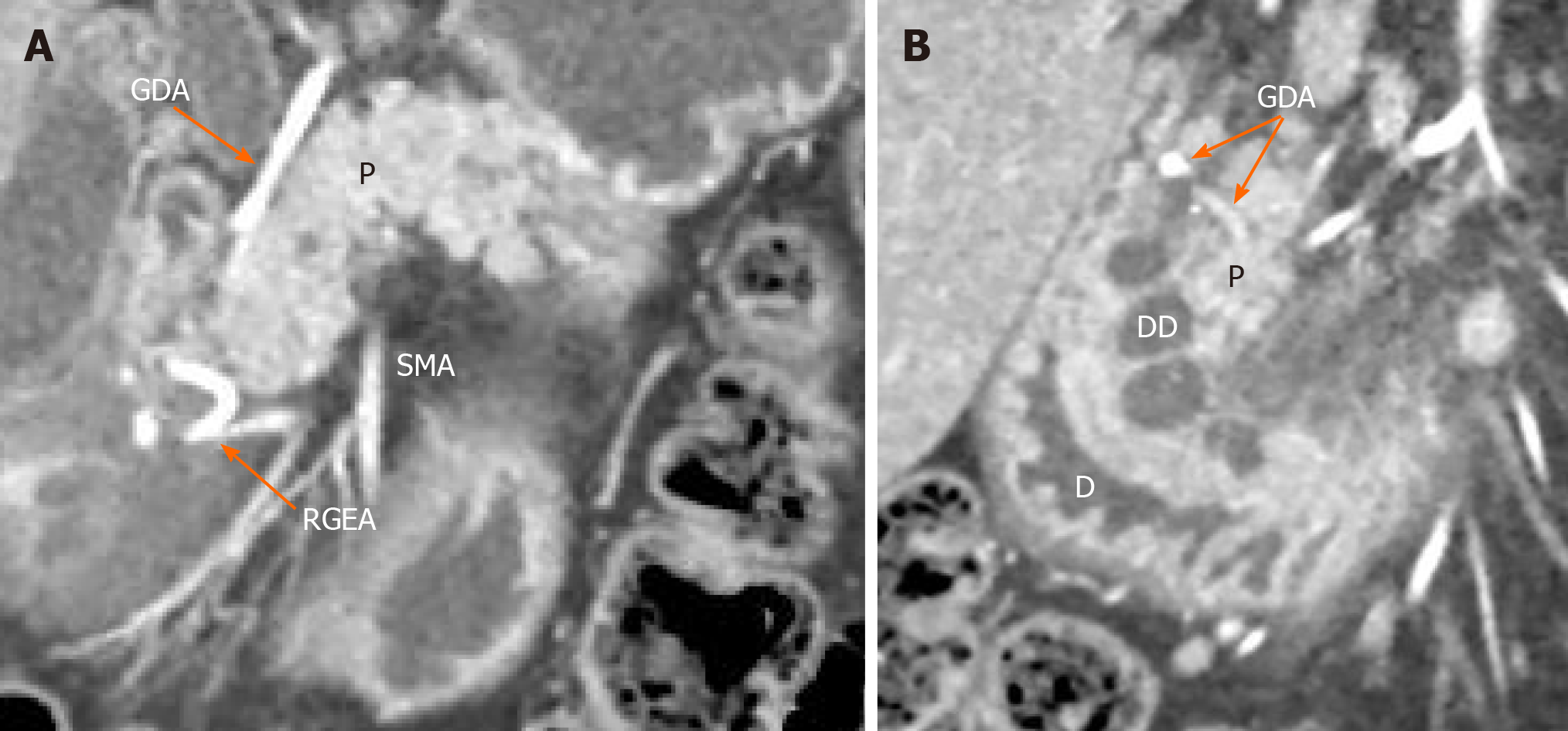

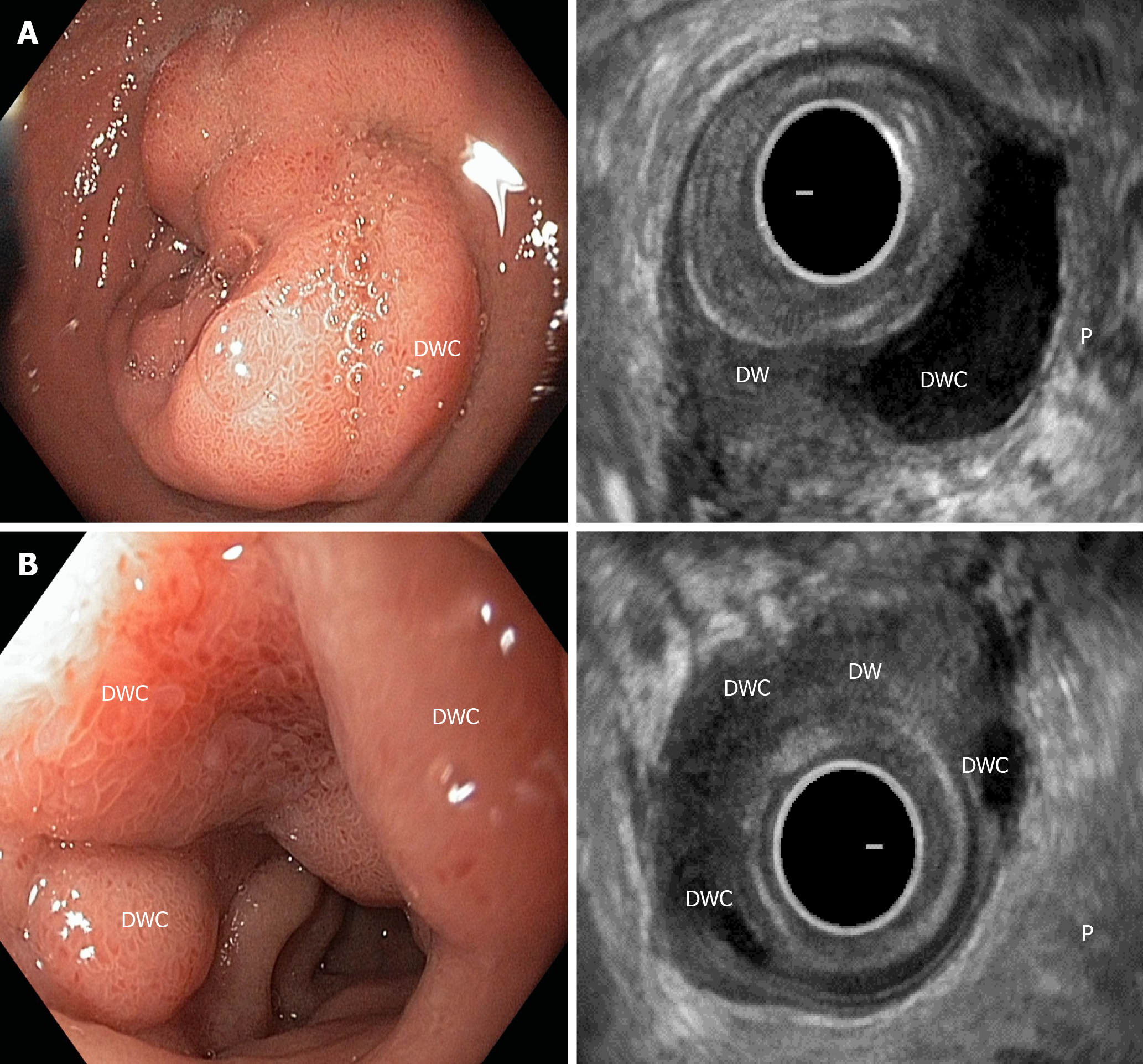

The diagnosis in all 59 patients who underwent PD and PPDR was clinically, radiologically and histologically confirmed. Eighteen patients (37%) demonstrated symptoms and signs of the isolated form of CDDW, as shown by computed tomography (CT) (Figure 2A and B), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and/or endoscopic ultrasonography (Figure 3A and B) (i.e., considerable (> 10 mm) thickening of the duodenal wall containing cystic cavities, separation of duodenal wall changes from the intact pancreas and antero-medial displacement of the gastroduodenal artery with respect to the pathological focus within the duodenum)[3,28,29].

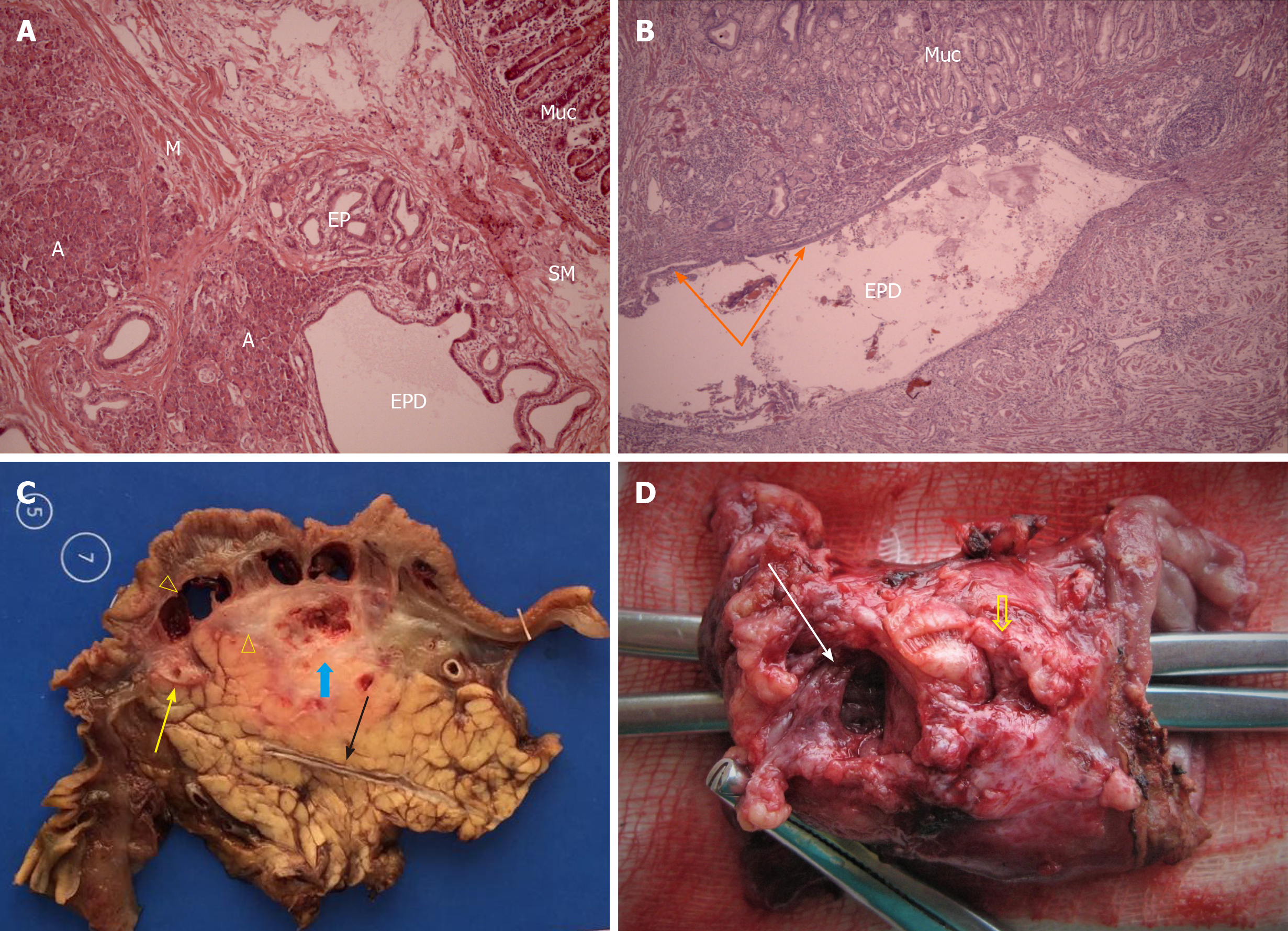

Histological diagnosis of CDDW was based on the detection of a cystic cavity or cavities in the duodenal wall, completely isolated from the pancreas, surrounded by areas of inflammation, fibrosis, and Brunner’s gland hyperplasia. These cavities could contain fragments of ectopic pancreatic tissue, being postnecrotic cysts, or distended ectopic pancreatic ducts with preserved or desquamated epithelium (Figure 4A-D).

The diagnosis of CP in the orthotopic gland was based on the criteria presented elsewhere[1,2,8,15]. When histologic examination of the duodenum and/or pancreas was not possible during the course of management of CDDW (n = 25), the diagnosis was based on pathognomonic findings of CT, MRI, and endoscopic ultrasonography according to the Cambridge and Rosemont criteria[3,4,6,10,17,28,29-32]. PPDR was considered possible and indicated if only the duodenum was involved and in the absence of pancreatic duct calculi or calcification, cysts and fibrotic changes in the pancreatic parenchyma (Cambridge Class 0-1 and/or less than three Rosemont criteria)[10,30-32].

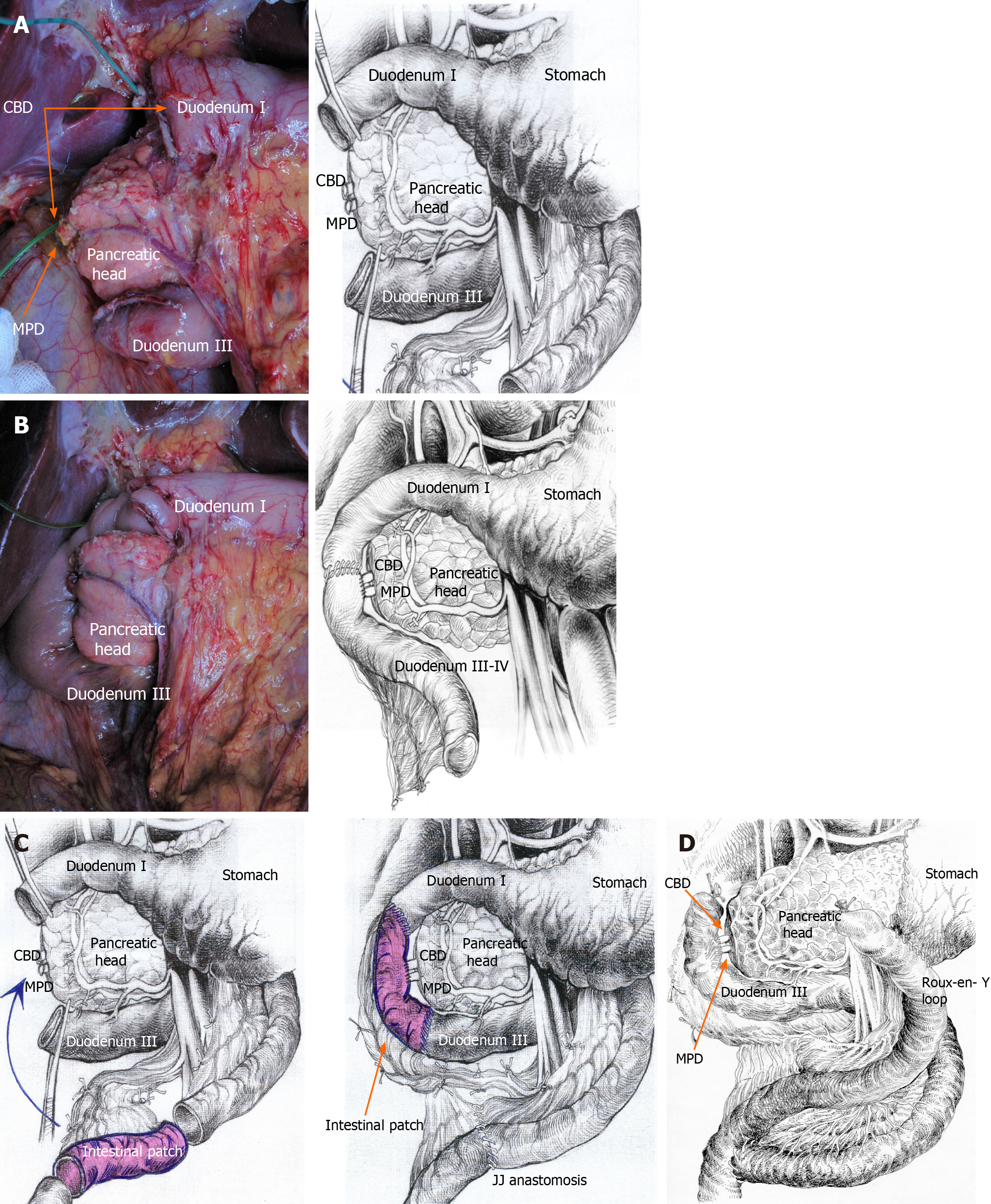

Pancreas-preserving surgery for CDDW was described previously[6,25], and we want to note a few details (Figure 5A-D). If the affected area of the second duodenal portion does not exceed 4 cm, a segmental resection of this part of the duodenum followed by duodeno-duodenostomy is possible. However, tension may be a limitation for this type of reconstruction, especially if the inflammatory zone spreads wider. In this case, intestinal interposition can be an option (Figure 5B), as well as classical duodenectomy (Figure 5C) or Roux-en-Y reconstruction (Figure 5D).

If inflammatory and fibrotic changes around the duodenum are moderate, it is possible to remove all the walls of the duodenal cyst without causing damage to the pancreas (Figure 4C)[25]. However, when significant fibrosis is present, it is preferable to keep the medial cystic wall intact to prevent possible damage to the pancreatic head[6]. This does not predispose to relapse, since the cysts lack epithelium due to chronic inflammation. Intraoperative biopsy of the resected portion of the duodenum is essential to exclude malignancy[33-35].

When inflammation and fibrosis extended beyond the second portion of the duodenum, we opted for the standard subtotal duodenectomy described by Chung et al[36] (Figure 5A and B)[37].

If the cyst extended to the first portion of the duodenum and/or stomach or if there was a peptic duodenal, pyloric or pre-pyloric ulcer, an antrectomy or pylorus resection with subsequent Roux-en-Y reconstruction was performed. Roux-en-Y reconstruction after ppPD PPDR is also an option if the surgeon sees reasons to separate the biliopancreatic tract from the food passage (Figure 5C).

All patients suffering from exocrine insufficiency received mini-microspheres of pancreatin (Creon®) at doses eliminating diarrhea, at least 200000 U/d before surgery. Pancreatin was continued for three months following the operation, at 240-320000 U/d. PERT was stopped if no signs of pancreatic insufficiency were observed after surgery.

The results of CDDW treatment were monitored for a period of 3 to 188 mo. The following information was recorded: Initial body weight, body weight at presentation, weight loss prior to the treatment, weight changes after 12-24 mo following surgery or treatment initiation (i.e., when most notable body weight changes are generally observed). Body weight and weight gain were defined based on the data acquired at the visit or provided in an information letter.

The pain level and rate were assessed using the Izbicki score[38]. Patients were contacted by telephone between the beginning and the end of July 2020 to evaluate the clinical, imaging and laboratory data.

All data distribution was evaluated by the Shapiro-Wilk test of normality in frequentist statistics. Demographic or clinical characteristics such as the average age, the proportion of subjects of each sex, the symptoms, etc., have been reflected by non-parametric descriptive statistics. The mean in variables was expressed as the median (Me) and interquartile range (LQ-UQ). Subgroups were compared using the Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis tests, as appropriate. P = 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and confidence intervals were calculated at 95%. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software program, version 20.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States).

The patient flow chart is presented in Figure 1. The treatment types and short- and long-term results are shown in Table 1.

| Type of treatment | n | 1Morbidity n (%) | Full pain control, n (%) | Steatorrhea, n (%) | New DM, n (%) |

| Conservative | 12 | 5 (42%) | 5 (42) | 4 (33) | 6 (50) |

| Draining OP | 8 | 1/1 (12.5/12.5%) | 2 (25) | 2 (25) | 2 (25) |

| DPPHR | 6 | 1/2 (17/34%) | 2 (33) | ||

| PD | 44 | 12/7 (27/16%) | 37 (84) | 6 (14) | 12 (31) |

| PPDR | 15 | 4/1 (27/7%) | 14 (93) |

By April 2020, only 12 patients were left in the conservative therapy group due to rejection of surgery. One patient died of heart failure after two myocardial infarctions 7 years after the onset of the disease. Although the patients in this subgroup did not undergo surgery, 2 of them died during observation and 6 complications were observed: Migration of a stent that drained the duodenal wall cyst into the duodenal lumen (n = 1), gastrointestinal bleeding associated with NSAID administration (n = 4), and ectopic pancreas malignization with multiple liver metastases and death after 7 years of monitoring and 10 years of the disease. Pain completely resolved in 5 patients in this subgroup but at the expense of “burning out” of the pancreas, which manifested with exocrine and endocrine insufficiency. The median time of follow-up in this subgroup was 93 mo (LQ-UQ: 78-111).

With the exception of one patient from the conservative therapy subgroup (ASA class III), all other patients had ASA class II physical status.

Draining procedures were carried out between 2004 and 2008, when we treated CDDW by the methods traditionally used for CP. In this subgroup, only 2 of 8 patients became pain-free, but due to a “burned out” pancreas, both patients developed diabetes and exocrine insufficiency. Postoperatively, two patients developed gastrointestinal hemorrhage. In 2008, we stopped performing draining procedures because of their inefficiency. However, all patients in this subgroup refused reoperation. One patient died 10 years after surgery due to heart failure. Median follow-up before surgery was 48 mo (LQ-UQ: 42-66) and after surgery was 142 mo (LQ-UQ: 123-144).

Six patients with CDDW associated with diffuse CP underwent DPPHR due to substantial enlargement of the pancreatic head. One patient was subjected to ppPD with pain relapse one year after the DPPHR. Three patients developed post-operative complications (gastrointestinal bleeding, grade B pancreatic fistula and acute pancreatitis). Only two patients achieved complete pain relief. None suffered from or developed exocrine insufficiency or diabetes. Median follow-up before surgery was 36 mo (LQ-UQ: 29-48) and after surgery was 120 mo (LQ-UQ: 105-133).

The three aforementioned subgroups did not include patients with the isolated form of CDDW.

The PD group included 29 ppPD, 11 classic PDs, and 4 Nakao procedures (Tables 2 and 3). Three patients underwent surgery for an isolated form of CDDW and the rest for CDDW associated with CP. Complete pain control was achieved in 84% of these patients. Seven patients (17%) developed major postoperative complications: Grade B pancreatic fistula (n = 3), gastrointestinal bleeding (n = 1), grade B delayed gastric emptying (n = 6) and intraoperative ureter electric trauma in the presence of pronounced retroperitoneal fibrosis (n = 1). Pancreatic fistulas developed only in patients with isolated CDDW. In one patient (No. 43), early ductal adenocarcinoma was found in an ectopic pancreas. Four patients had steatorrhea, and 5 had either diabetes or glucose intolerance prior to surgery. Twelve patients developed new diabetes and 6 developed steatorrhea after surgery. One patient in this group had ankylosing spondylitis. One patient died from myocardial infarction 14 years after PD, and four patients died 5.5, 5.5, 11 and 14.5 years after surgery of unknown cause. Four patients were lost to follow-up 185, 167, 164 and 159 mo after surgery. Median follow-up was 42 mo (LQ-UQ: 36-60) pre-operatively and 98 mo (LQ-UQ: 67-138) post-operatively. Thirty-seven patients (84%) were alcohol drinkers, and 33 (75%) were tobacco users before surgery After surgery, seven patients still smoke, and five still drink. After surgery, six patients had episodes of pancreatitis and 4 of them were hospitalized at least once due to this reason.

| Age | Pain | Vomi-ting | Jaundice | Weight loss, kg | Weight gain after surgery, kg | Weight gain after surgery, % | PERT after surgery | Pain after surgery, status, events | Treatment before surgery, mo | Follow-up after surgery, mo, status, events | |

| 1 | 44 | 37.8 | - | + | 6 | 9 | 150 | Yes | No, DM | 72 | 188, NA |

| 2 | 49 | 63 | - | 12 | 5 | 41 | Yes | No, drinking, NDM | 84 | 151, death of unknown cause | |

| 3 | 56 | 73.8 | - | 9 | 9 | 100 | Yes | No, steatorrhea. Smoking, DM | 54 | 166, death of MI | |

| 4 | 49 | 37.8 | + | + | 10 | 8 | 80 | Yes | No, NDM | 96 | 170, NA |

| 5 | 55 | 81.3 | + | + | 12 | 6 | 50 | Yes | 31.5, drinking, NDM, steatorrhea | 79 | 167, NA |

| 6 | 52 | 73.8 | - | 12 | 9 | 75 | Yes | No | 50 | 162, NA | |

| 7 | 39 | 73.8 | - | 15 | 11 | 73 | Yes | 31.5, smoking, DM | 60 | 167 | |

| 8 | 43 | 63 | +++ | 21 | 10 | 48 | Yes | No | 48 | 164 | |

| 9 | 55 | 73.8 | +++ | 18 | 13 | 72 | Yes | No, smoking | 38 | 162 | |

| 10 | 39 | 63 | ++ | 17 | 12 | 71 | No | No | 60 | 156 | |

| 11 | 57 | 73.8 | - | 6 | 6 | 100 | Yes | No, NDM | 8 | 69, death of unknown cause | |

| 12 | 40 | 73.8 | - | 11 | 8 | 78 | Yes | No | 36 | 155 | |

| 13 | 51 | 77.5 | - | 10 | 6 | 60 | Yes | 37.8 | 36 | 152 | |

| 14 | 61 | 81.3 | ++ | 8 | 6 | 75 | Yes | No, steatorrhea, NDM | 48 | 132, death of unknown cause | |

| 15 | 49 | 73.8 | +++ | 14 | 8 | 57 | Yes | 37.8, NDM | 72 | 147 | |

| 16 | 48 | 77.5 | ++ | + | 12 | 7 | 58 | Yes | 31.5, drinking, smoking | 31 | 147 |

| 17 | 40 | 63 | + | 13 | 7 | 54 | No | no | 60 | 141 | |

| 18 | 53 | 77.5 | - | 7 | 7 | 100 | Yes | no | 48 | 129 | |

| 19 | 59 | 31.5 | + | + | 13 | 9 | 69 | Yes | No, steatorrhea | 36 | 126 |

| 20 | 46 | 77.5 | - | 12 | 7 | 58 | Yes | No | 36 | 120 | |

| 21 | 45 | 73.8 | ++ | 8 | 5 | 62.5 | Yes | No, drinking | 41 | 117 | |

| 22 | 59 | 73.8 | ++ | 5 | 5 | 100 | Yes | No | 62 | 111 | |

| 23 | 50 | 31.5 | - | 5 | 7 | 140 | Yes | No, smoking | 48 | 107 | |

| 24 | 53 | 81.3 | +++ | 16 | 9 | 56 | Yes | No | 66 | 105 | |

| 25 | 47 | 37.8 | ++ | + | 10 | 8 | 80 | Yes | No | 54 | 103 |

| 26 | 44 | 63 | - | 10 | 7 | 70 | Yes | No | 48 | 101 | |

| 27 | 46 | 63 | +++ | 19 | 10 | 52 | Yes | No, steatorrhea, NDM | 36 | 97 | |

| 28 | 51 | 63 | +++ | 14 | 11 | 78.6 | Yes | No | 36 | 93 | |

| 29 | 37 | 77.5 | +++ | 15 | 9 | 60 | No | No | 40 | 93 | |

| 30 | 54 | 73.8 | ++ | 10 | 8 | 80 | Yes | No, DM | 48 | 69, death of unknown cause | |

| 31 | 52 | 31.5 | - | + | 12 | 8 | 67 | Yes | No, drinking, NDM | 66 | 85 |

| 32 | 53 | 67.5 | - | 12 | 10 | 83 | Yes | 31.5 | 24 | 85 | |

| 33 | 49 | 77.5 | ++ | 15 | 6 | 40 | Yes | No, steatorrhea | 12 | 79 | |

| 34 | 46 | 81.3 | + | 13 | 9 | 69 | Yes | No | 9 | 69 | |

| 35 | 48 | 37.8 | ++ | + | 15 | 10 | 67 | Yes | No | 16 | 69 |

| 36 | 50 | 63 | ++ | 14 | 9 | 64 | Yes | No | 32 | 69 | |

| 37 | 51 | 81.3 | - | 7 | 6 | 86 | Yes | No, smoking | 39 | 60 | |

| 38 | 58 | 31.5 | - | 11 | 8 | 73 | Yes | No, NDM, smoking | 42 | 57 | |

| 39 | 54 | 37.8 | - | 12 | 8 | 67 | Yes | No | 30 | 52 | |

| 40 | 49 | 73.8 | ++ | 8 | 6 | 75 | Yes | No | 36 | 45 | |

| 41 | 47 | 77.5 | ++ | 7 | 6 | 86 | Yes | No, DM | 120 | 20 | |

| 42 | 58 | 37.8 | - | 12 | 8 | 67 | Yes | No, NDM | 72 | 18 | |

| 43 | 47 | 73.8 | + | 11 | 1 | 9 | Yes | No, NDM | 66 | 13 | |

| 44 | 45 | 77.5 | +++ | 21 | 5 | 23 | Yes | No | 63 | 6 |

| No. | Procedure | Blood loss, mL | Time, min | Postop stay | Morbidity (Сlavien-Dindo) |

| 1 | pPD | 130 | 290 | 16 | Grade I, DGE A |

| 2 | pPD | 150 | 310 | 11 | No |

| 3 | pPD | 50 | 230 | 14 | No |

| 4 | PD | 460 | 370 | 31 | Grade IV, GI bleeding |

| 5 | pPD | 500 | 350 | 18 | Grade I, pneumonia |

| 6 | PD | 120 | 305 | 10 | No |

| 7 | pPD | 150 | 290 | 10 | No |

| 8 | pPD | 100 | 280 | 10 | Grade I, DGE A |

| 9 | PD | 230 | 300 | 12 | No |

| 10 | pPD | 50 | 185 | 25 | Grade III, POPF B |

| 11 | PD | 100 | 340 | 12 | No |

| 12 | pPD | 100 | 270 | 14 | No |

| 13 | pPD | 130 | 220 | 15 | Grade I, DGE A |

| 14 | pPD | 140 | 280 | 16 | Grade I, Lymphorrhea |

| 15 | pPD | 50 | 270 | 11 | No |

| 16 | PD | 50 | 280 | 12 | No |

| 17 | pPD | 120 | 210 | 36 | Grade III, POPF B, DGE B |

| 18 | pPD | 70 | 225 | 10 | No |

| 19 | PD | 750 | 480 | 41 | Grade III, ureter intraoperative trauma, DGE B |

| 20 | pPD | 100 | 200 | 9 | No |

| 21 | pPD | 100 | 200 | 7 | No |

| 22 | pPD | 150 | 240 | 14 | No |

| 23 | Nakao | 100 | 330 | 27 | Grade III, DGE B |

| 24 | pPD | 50 | 230 | 16 | Grade I, short-term bile leakage |

| 25 | pPD | 50 | 280 | 11 | No |

| 26 | Nakao | 100 | 350 | 12 | Grade I, DGE A |

| 27 | pPD | 120 | 250 | 10 | No |

| 28 | pPD | 140 | 260 | 9 | No |

| 29 | pPD | 50 | 170 | 28 | Grade III, POPF B, DGE B |

| 30 | Nakao | 100 | 310 | 14 | Grade I, short-term bile leakage |

| 31 | PD | 120 | 290 | 12 | No |

| 32 | Nakao | 100 | 320 | 13 | No |

| 33 | pPD | 100 | 190 | 27 | Grade III, DGE B |

| 34 | pPD | 100 | 300 | 10 | Grade I, lymphocele |

| 35 | PD | 100 | 320 | 11 | No |

| 36 | pPD | 350 | 310 | 11 | Grade I, wound infection |

| 37 | pPD | 50 | 300 | 13 | No |

| 38 | pPD | 50 | 270 | 12 | No |

| 39 | pPD | 50 | 240 | 14 | Grade I, DGE A |

| 40 | pPD | 50 | 230 | 11 | Grade I, POPF A |

| 41 | PD | 100 | 230 | 10 | No |

| 42 | pPD | 150 | 410 | 12 | No |

| 43 | PD | 270 | 390 | 11 | No |

| 44 | PD | 250 | 440 | 10 | No |

PPDR group. Tables 4 and 5 present demographic data, operative details, complications, and monitoring notes for patients undergoing PPDR. All patients were males with a mean age of 44.7 years (28-62 years). The mean body weight loss was 15.9 kg (5-44 kg). All patients suffered from pain of varying severity. Constant or frequent debilitating pain was recorded in 7 patients (46.6%). In 4 patients (26.6%), vomiting was associated with duodenal obstruction, whereas 3 patients (20%) had obstructive jaundice. Seven patients (46.6%) were addicted to alcohol, and 9 (60%) were active tobacco users before surgery. After surgery, three patients still smoke and one still drinks. There were no patients with exocrine or endocrine insufficiency either before or after surgery.

| No. | Age | Pain | Vomit | Jaundice | Weight loss, kg | Weight gain after surgery, kg | Weight gain after surgery, % | PERT after surgery | Pain after surgery, status, events | Treatment before surgery, mo | Follow-up after surgery, mo |

| 1 | 53 | 31.5 | +++ | + | 44 | 46 | 105 | No | No | 9.5 | 127 |

| 2 | 43 | 37.8 | +++ | + | 21 | 18 | 86 | No | No | 10 | 124 |

| 3 | 47 | 62.5 | - | 18 | 16 | 89 | No | No | 13 | 118 | |

| 4 | 45 | 81.3 | +++ | 23 | 16 | 70 | Yes | Pain 26.3, still drinking | 7 | 116 | |

| 5 | 41 | 62.5 | + | 11 | 8 | 73 | No | No | 11 | 110 | |

| 6 | 46 | 62.5 | + | 9 | 8 | 89 | No | No | 8 | 108 | |

| 7 | 28 | 67.5 | - | 5 | 3 | 60 | No | No | 8.5 | 104 | |

| 8 | 30 | 73.8 | - | 6 | 8 | 75 | No | No | 9 | 103 | |

| 9 | 56 | 77.5 | - | 14 | 10 | 71 | No | No, smoking | 10.5 | 101 | |

| 10 | 40 | 68.8 | + | 12 | 8 | 67 | No | No, smoking | 12 | 98 | |

| 11 | 44 | 81.3 | - | 7 | 8 | 114 | No | No | 13.5 | 97 | |

| 12 | 52 | 37.8 | +++ | 31 | 24 | 77 | No | GI bleeding -DP 46 mo after surgery, no symptoms | 11.5 | 89 | |

| 13 | 29 | 77.5 | + | 6 | 8 | 86 | No | No, smoking | 11 | 68 | |

| 14 | 62 | 68.8 | + | + | 11 | 11 | 100 | No | No | 5 | 65 |

| 15 | 55 | 77.5 | ++ | 21 | 12 | 57 | No | No | 7 | 31 |

| No. | PPDR | Blood loss, mL | Time, min | Postop stay, d | Morbidity (Сlavien-Dindo) |

| 1 | Intest pouch | 150 | 280 | 14 | No |

| 2 | Standard | 200 | 310 | 15 | No |

| 3 | DDA | 50 | 250 | 21 | Grade I, POPF A |

| 4 | Intest pouch | 50 | 270 | 39 | Grade IV, upper DJA leakage, converted in Roux-en-Y |

| 5 | Standard | 100 | 270 | 12 | No |

| 6 | DDA | 50 | 260 | 18 | Grade I, POPF A |

| 7 | Standard | 50 | 220 | 12 | No |

| 8 | Standard | 150 | 245 | 12 | No |

| 9 | Standard | 100 | 235 | 11 | No |

| 10 | Standard | 100 | 200 | 17 | Grade I, POPFA |

| 11 | Roux-en-Y | 50 | 215 | 14 | No |

| 12 | Standard | 100 | 215 | 16 | No |

| 13 | Roux-en-Y | 50 | 195 | 15 | No |

| 14 | Roux-en-Y | 50 | 230 | 14 | Grade I, POPF A |

| 15 | Roux-en-Y | 50 | 225 | 16 | No |

| Mean value | 87 |

The main diagnostic imaging modalities included MRI (n = 13), CT (n = 14), and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS, n = 11). In all patients, CDDW was diagnosed prior to surgery. In the isolated form of CDDW, no or minimal abnormalities of the pancreas were observed and only the duodenum was involved. Main pancreatic duct dilation (> 4 mm) was observed in 6 patients (40%) and common bile duct dilation (> 10 mm) in 8 patients (53%). Minor duodenal papilla was not detected. Accessory pancreatic duct (Santorini’s duct) dilation or impairment was not observed. This subgroup included one patient with essential hypertension (No. 14) and two patients (No. 4 and No. 12) with ankylosing spondylitis. PPDR were standard (Chung et al[36]) in 7 patients (46.6%) who were reconstructed with duodeno-duodenal anastomosis in 2 (13.3%), intestinal interposition in 2 (13.3%) and Roux-en-Y reconstruction in 4 (26.6%) (Table 2). No postoperative mortality occurred in any of the groups.

In all patients with isolated CDDW, macroscopic and microscopic examinations demonstrated intramural duodenal cysts completely separated from the pancreatic head and Brunner’s gland hyperplasia of varying severity. The cysts were located in the medial (n = 14) and anterolateral duodenal walls (n = 1), abutted (n = 7) and surrounded the main pancreatic duct (MPD) (n = 5) and, in three cases, extended from the second portion of the duodenum towards the stomach. In 8 patients (53%) ectopic pancreatic tissue was identified at pathology, one of them with PanIN II. In 7 patients, the cysts matched the characteristics of postnecrotic cysts or were characterized as a dilated pancreatic duct with preserved or desquamated epithelium (Figure 2).

Four patients in this group developed minor complications (Clavien-Dindo grade I), and one patient (No. 4) suffered major postoperative complications (33.3%). All minor complications were grade A pancreatic fistulas (No. 3, No. 6, No. 10, and No. 14). Average length of hospital stay (with the exception of patient No. 4) was 15 (11-21) d (Table 3).

Patient No. 4 was reoperated on 19 d after PPDR with intestinal interposition due to leakage and bleeding from the proximal duodeno-enteranastomosis. This complication was successfully treated with antrectomy and Roux-en-Y reconstruction. The rest of the patients were discharged without complications, and there were no readmissions within the next 90 d.

Patient No. 12 developed recurrent gastric bleeding due to rupture of a splenic artery aneurysm 46 mo after PPDR, having been asymptomatic all this period. Splenic artery aneurysm rupture led to retroperitoneal hematoma, splenic vein thrombosis, sinistral portal hypertension, acute gastric varices formation and hemorrhage. This delayed complication was successfully treated with distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy. Currently, the patient remains asymptomatic. In this case, the decision regarding the primary operation was based on non-contrast MRI and EUS findings due to the patient’s allergy to intravenous contrast. Therefore, it is unclear whether the aneurysm developed after surgery or existed before.

Median follow-up prior to surgery was 10 mo (LQ-UQ: 8-12), and after surgery was 81 mo (LQ-UQ: 70-93). Currently, 14 of 15 patients have no complaints or symptoms (93.3%, Table 1). One patient (No. 4) with ankylosing spondylitis experienced a significant decrease in the frequency and intensity of pain episodes, despite regular alcohol consumption. All remaining patients had no episodes of pancreatitis or hospitalizations due to pancreatitis.

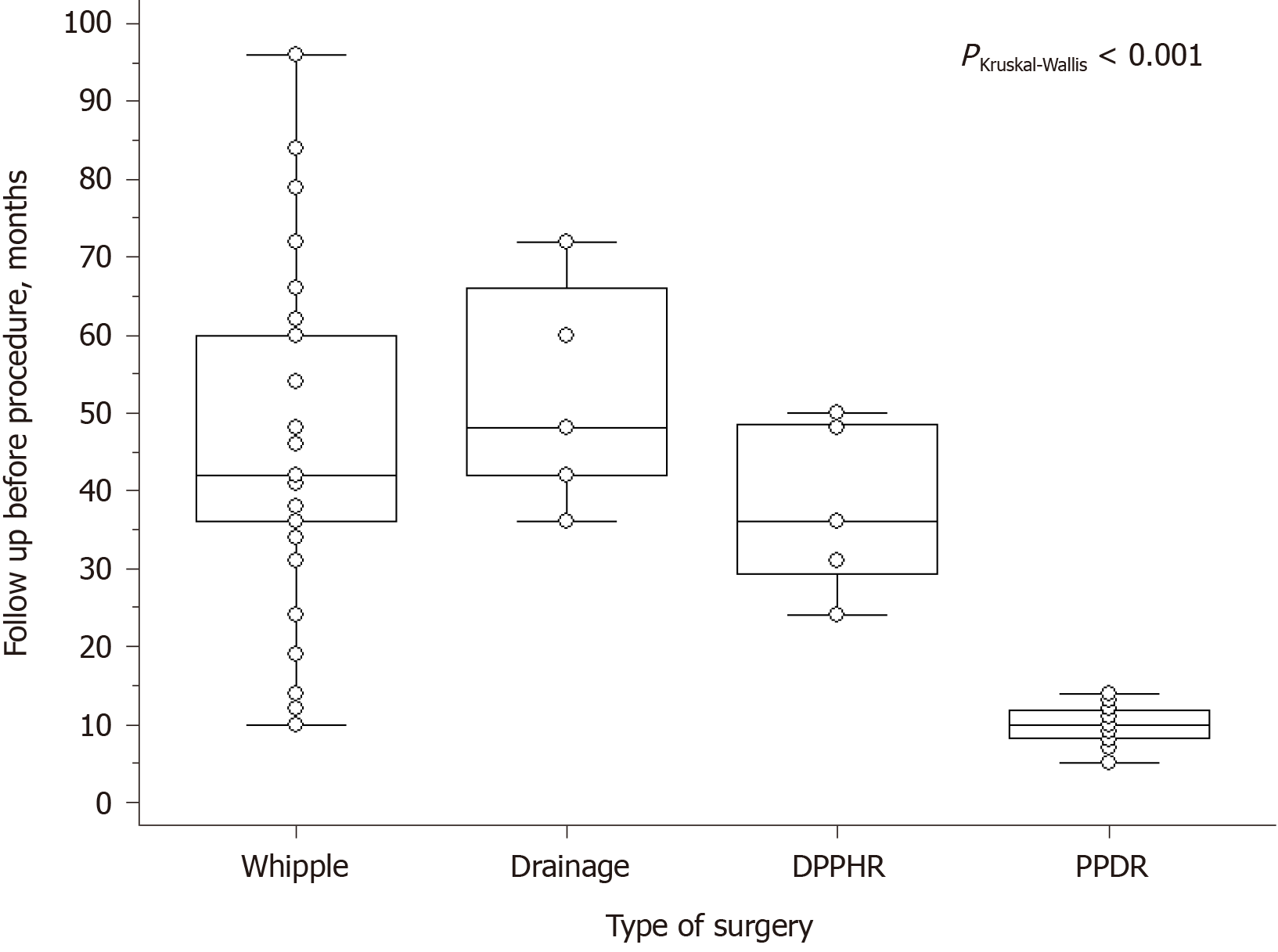

Short- and long-term results after PD and PPDR are shown in Tables 6-8. Follow-up before PPDR (Figure 6) was considerably shorter compared to other procedures.

| Variables | PPDR | PD | P M-W value |

| n | 15 | 44 | |

| Age, yr | 45 (40-52) | 49 (46-54) | 0.09 |

| Pain score | 69 (62.5-77.5) | 73.8 (63-73.8) | 0.08 |

| Weight loss, kg | 12 (7.5-21) | 12 (10.5-13) | 0.52 |

| Vomiting, n (%) | 5 (33) | 18 (41) | 0.53 |

| Jaundice, n (%) | 3 (25) | 8 (18) | 1 |

| Treatment before surgery, mo | 10 (8-12) | 45 (36-57) | 01 |

| Variables | PPDR | PD | P M-W value |

| n | 15 | 44 | |

| Blood loss, mL | 50 (50-100) | 50 (100-125) | 0.10 |

| Time, min | 235 (215-270) | 275 (240-290) | 0.05 |

| Hospital stay, d | 15 (13-17) | 12 (11-14) | 0.03 |

| Morbidity (Clavien-Dindo > III), n (%) | 1 (6) | 6 (14) | 0.67 |

Today, most pancreatologists recognize CDDW as a distinct form of CP[10,11]. Various terms have been used to define this condition, but all refer to the same set of clinical and histologic manifestations with typical imaging diagnostic criteria[3,28,29]. Despite the increasing number of publications on CDDW, it is difficult to define its true incidence and prevalence. Based on the data of large series from specialized centers, CDDW is identified in 13%-24% of patients who undergo surgery for CP; whereas the isolated form of CDDW (pure form of GP) was present in 22%-37% of all CDDW cases (Table 9).

| Ref. | Year | CDDW patients (n) | Pure form of CDDW | Surgery1 | PD2 | PPDR2 |

| Stolte et al[8] | 1982 | 30 | 11 (37%) | 30 (100%1) | 30 (100%) | - |

| Jouannaud et al[4] | 2006 | 23 | 0 | 14 (61%1) | 10 (71%) | - |

| Rebours et al[5] | 2007 | 105 | 30 (29%) | 29 (28%) | 17 (59%) | - |

| Tison et al[35] | 2007 | 9 | 5 (56%) | 9 (100%1) | 9 (100%) | - |

| de Pretis et al[17] | 2017 | 82 | 22 (27%) | 57 (69.5%1) | 51(89%) | - |

| Our data | 82 | 18 (22%) | 70 (85%) | 42 (60%) | 15 (21%) | |

| Overall | 331 | 86 | 209 | 159 | 15 |

At the time when we were not aware of the cause of CDDW and thought that the cystic lesion of the duodenal wall originated from the pancreatic head, we performed operations relevant to conventional CP, such as longitudinal pancreaticojejunostomy, pancreaticocystostomy and DPPHR. Due to high complications and low efficacy rates, we stopped practicing this procedure in any type of CDDW.

A comparison of short- and long-term results of the two most efficient methods of CDDW treatment, namely PD and PPDR (Tables 6-8 have shown that both groups were similar in most of the parameters. Preoperative follow-up in the PD group was significantly longer because of long-lasting efficient conservative treatment, including endoscopic options. Patients in the PPDR subgroup were operated on much earlier due to intensive and/or frequent pain, with such CDDW complications as duodenal obstruction and jaundice. There were no significant differences in intraoperative details and short-term results. In spite of the advantages of PPDR in this data sample, transfer to the general population did not reveal significant differences in morbidity, which was probably due to the small number of cases. Hospital stay was not significantly longer in the PPDR group, depending mainly on the peculiarities of the Russian Federation health care system relating to new treatment methods (Table 6).

Postoperative absolute and relative weight gain were higher in the PPDR group compared to the PD group, but not significantly so. New onset diabetes mellitus never occurred in the PPDR group, which was significantly better compared to 31% after PD. No patient required PERT after PPDR, which was significantly different compared to the PD group, where only two patients were PERT-free (Table 7). Six of our 44 patients (14%) suffered pain recurrence after PD, which is comparable to the results of the Italian studies (18.75%)[17].

Only one major complication was recorded after PPDR: Leakage of the proximal duodenojejunostomy, and it was caused by marked fibrosis of the duodenal bulb, due to a long history of peptic ulcer disease. This observation changed our practice so that patients with a history of peptic ulcer disease were subsequently subjected to Roux-en-Y reconstruction with no serious complications since then. It is important to note that a significant history of peptic ulcer is common in patients with CDDW due to stenosis of the second portion of the duodenum. One other remote complication was splenic artery aneurysm rupture, which occurred in one case four years after PPDR. The aneurysm was not detected before surgery, since no contrast CT had been carried out. The patient underwent distal pancreatectomy and subsequently returned to normal life. All minor complications were confined to short-term grade A pancreatic fistulas, which might have occurred due to suturing normal pancreatic parenchyma. After PPDR, all patients except one, achieved long-term improvement. No patients developed endocrine or exocrine pancreatic insufficiency due to preservation of the whole gland, which was only mildly affected.

As for derivative procedures, they were quite effective in the French experience[5], but in the Italian study[17], they failed in more than 60% of patients, which is very similar to our results.

Based on our data (Table 1) and the works of Italian and French colleagues[4,17], conservative treatment (including endoscopic) and draining procedures are ineffective when damaged pancreatic tissue is present in the context of CDDW, although there have been some reports of short-term positive results[7,17,23,39,40].

In our series, neither minor duodenal papilla, nor Santorini’s duct alterations were detected in the PPDR subgroup during pathologic examination. This corresponds to the radiological data by Wagner et al[41] and to Stolte et al[8] and Becker et al’s[9] histologic evidence. The latter also demonstrated that, in cases of CDDW, the minor duodenal papilla detection rate is 31%, which corresponds to the minor duodenal papilla distribution in the general population. All these findings are important to the surgeon making the decision to save or not to save the pancreas, and they do not argue for the importance of minor duodenal papilla and Santorini’s duct pathology in the development of CDDW.

The efficacy of pancreas-preserving duodenectomy for the isolated form of CDDW (i.e., pure form of GP) is important evidence indicating that, in the early stages of the disease the lesion is located in the duodenum, rather than in the pancreas or paraduodenal area.

It is worth mentioning that the imaging characteristics of CDDW are quite specific, so that preoperative diagnosis has become increasingly reliable[3,28,29,42,43]. Eighty three of 84 patients were diagnosed as having CDDW prior to the operation and only one was operated on due to “impossibility to rule out duodenal or pancreatic head tumor.” The same “learning curve” for radiologists is mentioned by our Italian colleagues[16].

The possibility of malignant transformation in ectopic pancreatic tissue should never be ruled out, although there have been only 15 such cases reported[30,31,32]. In our pool of 84 patients, one in the conservative therapy subgroup died of metastatic cancer of the ectopic pancreas, early cancer was found in the ectopic pancreas after PD in a second, and PanIN II epithelial dysplasia of the ectopic pancreas was diagnosed after PPDR in a third patient[27].

The limitations of the work are its retrospective design and the impossibility to compare PD and PPDR for the isolated form of CDDW only because of conventional practice and relative rarity of the disease. We tried to be strict in selecting only patients who abstained from smoking and alcohol consumption, but due to legislation in Russia, it is impossible to use opioids for CP treatment. As a result, we had to operate on patients with intractable pain. The same is true for such complications of CDDW as jaundice and duodenal obstruction, even if patients are still smoking and drinking.

The point of interest is the association of CDDW and ankylosing spondylitis in three patients in our series, which could be a topic of subsequent research.

In summary, CDDW is a distinctive form of CP. Its peculiarity lies in the fact that no or minimal damage to the orthotopic (main) pancreas occurs in its isolated form, while further development of the disease leads to involvement of the pancreas. The success of PPDR and the decreased probability of disease progression from its isolated form to segmental and, then, diffuse pancreatitis after PPDR, indicate that in the cases of CDDW: (1) PPDR may be the treatment of choice for the isolated form of CDDW; (2) Isolated CDDW, or the pure form of GP, is a disease of the duodenum; (3) Early detection of CDDW makes preservation of the pancreas possible; (4) PD appears to be overtreatment for the isolated form of CDDW, since it involves resection of undamaged pancreatic head parenchyma; (5) Prolonged conservative treatment in cases of the isolated form of CDDW may lead to the development of segmental and diffuse pancreatitis, which may deprive patients of the pancreas-preserving option; and (6) The abovementioned points make PPDR an alternative treatment for CDDW (GP).

Potet et al[1] and Stolte et al[8] and Becker et al[9] demonstrated that clinical and pathologic manifestations of GP might occur with no pancreas involvement. In these cases, the pathologic process is localized in the duodenum as intramural duodenal cysts, chronic inflammation of ectopic pancreatic tissue in the duodenal wall, and perifocal fibrosis. These observations are also supported by other studies[2-9,34]. This led to the conclusion that the pure form was an initial stage of GP, which is supported by our data regarding a much shorter time between the onset of the disease and the operation in the PPDR subgroup (Figure 6). Therefore, the disease is referred to by different authors as the isolated cystic form of CDDW[1,2-7], pure form of GP[8,9], or pure form of PP[17]. The groove between the duodenum and pancreas has no organs to be inflamed, and this leads to fibrotic changes of the groove; therefore, its cicatrization may only be caused by the involvement of adjacent organ(s). If we do not detect considerable alterations of the pancreatic head, but do detect changes in the duodenal wall, it would be reasonable to assume that inflammation of the duodenal wall caused cicatrization of the groove and the development of other symptoms. This means that the involvement of the duodenum is the primary factor, while damage to the pancreas comes second. The idea that CDDW, GP or PP is a duodenal disease is not new. All main investigators of the subject[5,8,15-17] unambiguously spoke about this. Some misunderstandings appeared when the pathologic examination was carried out in a series that only included cases of advanced disease (for example, 21 specimens in[15], or 20 specimens from 10 hospitals[4]). In all other large series, we can find specimens with isolated forms of CDDW (pure forms of GP) (Table 9). The organ of disease origin is impossible to establish in advanced stages with associated severe CP of the main gland[4,15,42,43].

These observations lead to two conclusions. The first is the adoption of a legitimate term to refer to the condition. If this stage of the disease is called groove or PP, we describe pancreatitis with no pancreatitis, since all alterations are concentrated in the duodenum. It does not seem reasonable to refer to a disease located in the duodenum as inflammation of the pancreas[44]. Along with that, CDDW sounds like a diagnosis referring to a specific organ and incorporation of this term appears as a more logical alternative. The second conclusion is that the removal of the damaged area (i.e., partial or total duodenectomy) may be the best possible method of treatment of the pure form of GP or PP[27].

It is important to differentiate between the pure and segmental forms of GP (isolated form of CDDW) in order not to confuse “typical signs or symptoms of the disease”[45,46]. These two forms of the disease may demonstrate the same clinical manifestations, but different typical signs, and based on the aforementioned data, may be treated differently.

The following conclusions were drawn: (1) PPDR may be the treatment of choice for the isolated form of CDDW; (2) Isolated CDDW, or the pure form of GP, is a disease of the duodenum; (3) Early detection of CDDW makes preservation of the pancreas possible; (4) PD appears to be overtreatment for the isolated form of CDDW, since it involves resection of undamaged pancreatic head parenchyma; (5) Prolonged conservative treatment in the isolated form of CDDW may lead to the development of segmental and diffuse pancreatitis, which may deprive patients of the pancreas-preserving option; and (6) the abovementioned points make PPDR a procedure that is changing the treatment of CDDW (GP).

Today most pancreatologists recognize groove pancreatitis as a distinct form of chronic pancreatitis, but the natural history of the disease and the optimal time for surgery are unknown.

To understand the best technique and timing of pancreas-preserving procedures for groove pancreatitis (GP).

To compare the results of conventional (Whipple procedure) and organ-preserving surgery for the treatment of GP.

A retrospective comparison of the different conservative and surgical modalities for the treatment of GP in 84 patients.

Timely pancreas-preserving procedures for GP are safe and provide better long-term results compared to conventional surgery, which is usually used at the late stages of the disease.

Pancreas-preserving duodenal resection (PPDR) may be the treatment of choice for the isolated form of GP; the pure form of GP is a disease of the duodenum, early detection of which makes preservation of the pancreas possible; prolonged conservative treatment in the isolated form of GP may lead to the development of segmental and diffuse pancreatitis, which may deprive patients of the pancreas-preserving option; timely performed PPDR is a treatment-changing procedure for GP.

If the author’s approach is widely accepted, more patients with GP will have the chance to save their pancreas, and prospective comparative trials will be possible on the above mentioned subject.

The authors would like to express appreciation to Löhr M, Rebours V and Tsiotos G for review and correction of the manuscript, to Bystrovskaya E for endoscopic and endoUS pictures, and to Maslennikov V for his drawings.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Russian Pancreatic Club; European Pancreatic Club; European-African Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Association; and The Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Russia

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Zhao CF S-Editor: Huang P L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Potet F, Duclert N. [Cystic dystrophy on aberrant pancreas of the duodenal wall]. Arch Fr Mal App Dig. 1970;59:223-238. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Fléjou JF, Potet F, Molas G, Bernades P, Amouyal P, Fékété F. Cystic dystrophy of the gastric and duodenal wall developing in heterotopic pancreas: an unrecognised entity. Gut. 1993;34:343-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Vullierme MP, Vilgrain V, Fléjou JF, Zins M, O'Toole D, Ruszniewski P, Belghiti J, Menu Y. Cystic dystrophy of the duodenal wall in the heterotopic pancreas: radiopathological correlations. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2000;24:635-643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jouannaud V, Coutarel P, Tossou H, Butel J, Vitte RL, Skinazi F, Blazquez M, Hagège H, Bories C, Rocher P, Belloula D, Latrive JP, Meurisse JJ, Eugène C, Dellion MP, Cadranel JF, Pariente A; Association Nationale des Hépato-Gastroentérologues des Hôpitaux généraux. Cystic dystrophy of the duodenal wall associated with chronic alcoholic pancreatitis. Clinical features, diagnostic procedures and therapeutic management in a retrospective multicenter series of 23 patients. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2006;30:580-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rebours V, Lévy P, Vullierme MP, Couvelard A, O'Toole D, Aubert A, Palazzo L, Sauvanet A, Hammel P, Maire F, Ponsot P, Ruszniewski P. Clinical and morphological features of duodenal cystic dystrophy in heterotopic pancreas. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:871-879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Egorov VI, Vankovich AN, Petrov RV, Starostina NS, Butkevich ATs, Sazhin AV, Stepanova EA. Pancreas-preserving approach to "paraduodenal pancreatitis" treatment: why, when, and how? Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:185265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Pezzilli R, Santini D, Calculli L, Casadei R, Morselli-Labate AM, Imbrogno A, Fabbri D, Taffurelli G, Ricci C, Corinaldesi R. Cystic dystrophy of the duodenal wall is not always associated with chronic pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4349-4364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Stolte M, Weiss W, Volkholz H, Rösch W. A special form of segmental pancreatitis: "groove pancreatitis". Hepatogastroenterology. 1982;29:198-208. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Becker V, Mischke U. Groove pancreatitis. Int J Pancreatol. 1991;10:173-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Löhr JM, Dominguez-Munoz E, Rosendahl J, Besselink M, Mayerle J, Lerch MM, Haas S, Akisik F, Kartalis N, Iglesias-Garcia J, Keller J, Boermeester M, Werner J, Dumonceau JM, Fockens P, Drewes A, Ceyhan G, Lindkvist B, Drenth J, Ewald N, Hardt P, de Madaria E, Witt H, Schneider A, Manfredi R, Brøndum FJ, Rudolf S, Bollen T, Bruno M; HaPanEU/UEG Working Group. United European Gastroenterology evidence-based guidelines for the diagnosis and therapy of chronic pancreatitis (HaPanEU). United European Gastroenterol J. 2017;5:153-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 521] [Cited by in RCA: 425] [Article Influence: 53.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Issa Y, van Santvoort HC, Fockens P, Besselink MG, Bollen TL, Bruno MJ, Boermeester MA; Collaborators. Diagnosis and treatment in chronic pancreatitis: an international survey and case vignette study. HPB (Oxford). 2017;19:978-985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Suda K, Takase M, Shiono S, Yamasaki S, Nobukawa B, Kasamaki S, Arakawa A, Suzuki F. Duodenal wall cysts may be derived from a ductal component of ectopic pancreatic tissue. Histopathology. 2002;41:351-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bill K, Belber JP, Carson JW. Adenomyoma (pancreatic heterotopia) of the duodenum producing common bile duct obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc. 1982;28:182-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Aoun N, Zafatayeff S, Smayra T, Haddad-Zebouni S, Tohmé C, Ghossain M. Adenomyoma of the ampullary region: imaging findings in four patients. Abdom Imaging. 2005;30:86-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Adsay NV, Zamboni G. Paraduodenal pancreatitis: a clinico-pathologically distinct entity unifying "cystic dystrophy of heterotopic pancreas", "para-duodenal wall cyst", and "groove pancreatitis". Semin Diagn Pathol. 2004;21:247-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Casetti L, Bassi C, Salvia R, Butturini G, Graziani R, Falconi M, Frulloni L, Crippa S, Zamboni G, Pederzoli P. "Paraduodenal" pancreatitis: results of surgery on 58 consecutives patients from a single institution. World J Surg. 2009;33:2664-2669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | de Pretis N, Capuano F, Amodio A, Pellicciari M, Casetti L, Manfredi R, Zamboni G, Capelli P, Negrelli R, Campagnola P, Fuini A, Gabbrielli A, Bassi C, Frulloni L. Clinical and Morphological Features of Paraduodenal Pancreatitis: An Italian Experience With 120 Patients. Pancreas. 2017;46:489-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Izbicki JR, Knoefel WT, Müller-Höcker J, Mandelkow HK. Pancreatic hamartoma: a benign tumor of the pancreas. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:1261-1262. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Wu SS, Vargas HI, French SW. Pancreatic hamartoma with Langerhans cell histiocytosis in a draining lymph node. Histopathology. 1998;33:485-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | McFaul CD, Vitone LJ, Campbell F, Azadeh B, Hughes ML, Garvey CJ, Ghaneh P, Neoptolemos JP. Pancreatic hamartoma. Pancreatology. 2004;4:533-537; discussion 537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Rubay R, Bonnet D, Gohy P, Laka A, Deltour D. Cystic dystrophy in heterotopic pancreas of the duodenal wall: medical and surgical treatment. Acta Chir Belg. 1999;99:87-91. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Bittar I, Cohen Solal JL, Cabanis P, Hagege H. [Cystic dystrophy of an aberrant pancreas. Surgery after failure of medical therapy]. Presse Med. 2000;29:1118-1120. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Basili E, Allemand I, Ville E, Laugier R. [Lanreotide acetate may cure cystic dystrophy in heterotopic pancreas of the duodenal wall]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2001;25:1108-1111. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Nakao A. Pancreatic head resection with segmental duodenectomy and preservation of the gastroduodenal artery. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:533-535. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Egorov VI, Butkevich AC, Sazhin AV, Yashina NI, Bogdanov SN. Pancreas-preserving duodenal resections with bile and pancreatic duct replantation for duodenal dystrophy. Two case reports. JOP. 2010;11:446-452. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Gloor B, Friess H, Uhl W, Büchler MW. A modified technique of the Beger and Frey procedure in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Dig Surg. 2001;18:21-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Frey CF, Mayer KL. Comparison of local resection of the head of the pancreas combined with longitudinal pancreaticojejunostomy (frey procedure) and duodenum-preserving resection of the pancreatic head (beger procedure). World J Surg. 2003;27:1217-1230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Yu J, Fulcher AS, Turner MA, Halvorsen RA. Normal anatomy and disease processes of the pancreatoduodenal groove: imaging features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:839-846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Graziani R, Tapparelli M, Malagò R, Girardi V, Frulloni L, Cavallini G, Pozzi Mucelli R. The various imaging aspects of chronic pancreatitis. JOP. 2005;6:73-88. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Catalano MF, Sahai A, Levy M, Romagnuolo J, Wiersema M, Brugge W, Freeman M, Yamao K, Canto M, Hernandez LV. EUS-based criteria for the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis: the Rosemont classification. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1251-1261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 373] [Cited by in RCA: 345] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Stevens T, Lopez R, Adler DG, Al-Haddad MA, Conway J, Dewitt JM, Forsmark CE, Kahaleh M, Lee LS, Levy MJ, Mishra G, Piraka CR, Papachristou GI, Shah RJ, Topazian MD, Vargo JJ, Vela SA. Multicenter comparison of the interobserver agreement of standard EUS scoring and Rosemont classification scoring for diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:519-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kalmin B, Hoffman B, Hawes R, Romagnuolo J. Conventional versus Rosemont endoscopic ultrasound criteria for chronic pancreatitis: comparing interobserver reliability and intertest agreement. Can J Gastroenterol. 2011;25:261-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Fukino N, Oida T, Mimatsu K, Kuboi Y, Kida K. Adenocarcinoma arising from heterotopic pancreas at the third portion of the duodenum. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:4082-4088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Betzler A, Mees ST, Pump J, Schölch S, Zimmermann C, Aust DE, Weitz J, Welsch T, Distler M. Clinical impact of duodenal pancreatic heterotopia - Is there a need for surgical treatment? BMC Surg. 2017;17:53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Tison C, Regenet N, Meurette G, Mirallié E, Cassagnau E, Frampas E, Le Borgne J. Cystic dystrophy of the duodenal wall developing in heterotopic pancreas: report of 9 cases. Pancreas. 2007;34:152-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Chung RS, Church JM, vanStolk R. Pancreas-sparing duodenectomy: indications, surgical technique, and results. Surgery. 1995;117:254-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Tsiotos GG, Sarr MG. Pancreas-preserving total duodenectomy. Dig Surg. 1998;15:398-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Bloechle C, Izbicki JR, Knoefel WT, Kuechler T, Broelsch CE. Quality of life in chronic pancreatitis--results after duodenum-preserving resection of the head of the pancreas. Pancreas. 1995;11:77-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Kager LM, Lekkerkerker SJ, Arvanitakis M, Delhaye M, Fockens P, Boermeester MA, van Hooft JE, Besselink MG. Outcomes After Conservative, Endoscopic, and Surgical Treatment of Groove Pancreatitis: A Systematic Review. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51:749-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | de Parades V, Roulot D, Palazzo L, Chaussade S, Mingaud P, Rautureau J, Coste T. [Treatment with octreotide of stenosing cystic dystrophy on heterotopic pancreas of the duodenal wall]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1996;20:601-604. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Wagner M, Vullierme MP, Rebours V, Ronot M, Ruszniewski P, Vilgrain V. Cystic form of paraduodenal pancreatitis (cystic dystrophy in heterotopic pancreas (CDHP)): a potential link with minor papilla abnormalities? Eur Radiol. 2016;26:199-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Aguilera F, Tsamalaidze L, Raimondo M, Puri R, Asbun HJ, Stauffer JA. Pancreaticoduodenectomy and Outcomes for Groove Pancreatitis. Dig Surg. 2018;35:475-481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Raman SP, Salaria SN, Hruban RH, Fishman EK. Groove pancreatitis: spectrum of imaging findings and radiology-pathology correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;201:W29-W39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Arora A, Rajesh S, Mukund A, Patidar Y, Thapar S, Arora A, Bhatia V. Clinicoradiological appraisal of 'paraduodenal pancreatitis': Pancreatitis outside the pancreas! Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2015;25:303-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Kim JD, Han YS, Choi DL. Characteristic clinical and pathologic features for preoperative diagnosed groove pancreatitis. J Korean Surg Soc. 2011;80:342-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Goldaracena N, McCormack L. A typical feature of groove pancreatitis. HPB (Oxford). 2012;14:487-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |