Published online Aug 27, 2020. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v12.i8.369

Peer-review started: May 7, 2020

First decision: May 15, 2020

Revised: June 2, 2020

Accepted: August 4, 2020

Article in press: August 4, 2020

Published online: August 27, 2020

Processing time: 105 Days and 22.3 Hours

Post-operative enteral nutrition via gastric or jejunal feeding tubes is a common and standard practice in managing the critically ill or post-surgical patient. It has its own set of complications, including obstruction, abscess formation, necrosis, and pancreatitis. We present here a case of small bowel obstruction caused by enteral nutrition bezoar. It is the second recorded incidence of this complication after pancreaticoduodenectomy in the medical literature.

The 70-year-old female presented to our institution for a pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple’s procedure) for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. On day 5 post-operative, having failed to progress and developing symptoms of small bowel obstruction, she underwent a computed tomography scan, which showed features of mechanical small bowel obstruction. Following this, she underwent an emergency laparotomy and small bowel decompression. The recovery was long and protracted but, ultimately, she was discharged home. A literature search of reports from 1966-2020 was conducted in the MEDLINE database. We identified eight articles describing a total of 14 cases of small bowel obstruction secondary to enteral feed bezoar. Of those 14 cases, all but 4 occurred after upper gastrointestinal surgery; all but 1 case required further surgical intervention for deteriorating clinical picture. The postulated causes for this include pH changes, a reduction in pancreatic enzymes and gastric motility, and the use of opioid medication.

Enteral feed bezoar is a complication of enteral feeding. Despite rare incidence, it can cause significant morbidity and potential mortality.

Core tip: Enteral feed bezoar is a complication of enteral feeding in the post-operative or critically ill patient. We present the second case in the literature of small bowel obstruction due to enteral nutrition solidification after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Although incidence is rare, it can have significant morbidity and potential mortality. Eight articles summarize 14 cases in the medical literature. Due to a combination of vague symptoms and vulnerable patient cohort, it can have extensive morbidity, with 13/14 cases requiring a second laparotomy. High clinical suspicion and low threshold for return to theatre is advised for these deteriorating patients.

- Citation: Siddens ED, Al-Habbal Y, Bhandari M. Gastrointestinal obstruction secondary to enteral nutrition bezoar: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 2020; 12(8): 369-376

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v12/i8/369.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v12.i8.369

Post-operative enteral nutrition (EN) via gastric or jejunal feeding tubes is a common and standard practice in managing the critically ill patient or post-operative surgical patient with functioning small bowel[1]. It is preferred over total parenteral nutrition (TPN), as it prevents mucosal atrophy and bacterial translocation while preserving intestinal integrity. However, EN it associated with the following complications: Aspiration, malposition, re-feeding syndrome, and solidification. Although rare, solidification of EN brings with it its own set of serious complications, including small bowel obstruction, necrosis, mural abscesses, perforation and pancreatitis[2]. Specifically, small bowel obstruction secondary to EN bezoar has been recorded only 14 times, much less than oesophageal or gastric bezoar, which have been reported 45 times[3]. The vast majority of the literature states that treatment is an emergency laparotomy and decompression and potentially a bowel resection, depending on the operative findings.

The 70-year-old female was electively admitted to our institution for an open pancreaticoduodenectomy for the treatment pancreatic adenocarcinoma. The patient had the chief complaint of painless jaundice.

The jaundice had arisen insidiously over a 6-mo period. It was associated with weight loss and poor appetite. Extensive investigations had been performed, including computed tomography of the chest, abdomen and pelvis, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, endoscopic ultrasound, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, and positive emission topography scan. She had also had a diagnostic laparoscopy.

The patient’s only past medical history included an open appendectomy for appendicitis.

As per unit and hospital protocol, immediately post-operation, the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) with nasojejunal (NJ) feeding tube. EN commenced 6 h post-operation at 30 mL/h. She required no vasopressor support and on day 1 had the feed rate increased. She was transferred to the surgical ward and the only concern in the immediate post-operative period was high nasogastric (NG) output. This initially improved, and slowly oral intake was introduced. She was prescribed an osmotic laxative at this time.

On day 5, the patient developed nausea and vomiting, with increasing pain in her central abdomen. Clinically, she had a mild tachycardia and central abdominal tenderness. The initial differential diagnosis of the presentation was postoperative anastomotic leak, particularly supported by the sudden deterioration in clinical picture and timing of the deterioration. Other differentials included postoperative collection and small bowel obstruction, potentially caused by internal hernia. To investigate, a computed tomography was organized; the finding was a large volume of fluid in distal thoracic esophagus and stomach. The tip of the NJ feeding tube was located appropriately within the efferent small bowel loop. There were also features of proximal to mid small bowel obstruction with faecalisation (Figure 1). The transition point was not clearly defined (Figure 2). Adhesions were postulated as a possible cause.

Small bowel obstruction caused by EN solidification.

According to the patient’s imaging findings, a laparotomy was performed. Intra-operatively, her small bowel distension had caused multiple serosal tears. One of these was full thickness, causing faecal and feed contamination of the peritoneum (Figure 3). She underwent decompression of her small bowel, extensive washout and enterotomy repair. The anaesthetic team replaced her NJ feeding tube with a standard large bore NG tube, and a central venous catheter was placed to facilitate the commencement of TPN. The patient had a second admission to the ICU for inotropic support and worsening acute kidney injury. Antifungal treatment was added to her existing antibiotic regimen.

The patient’s post-operative recovery was slow, with wound dehiscence and intra-abdominal collection; the latter was managed with percutaneously inserted drains. She resumed oral intake on day 15 post-laparotomy and continued on nourishing fluids until discharge. Her wound dehiscence required regular dressing changes and then negative-pressure wound therapy.

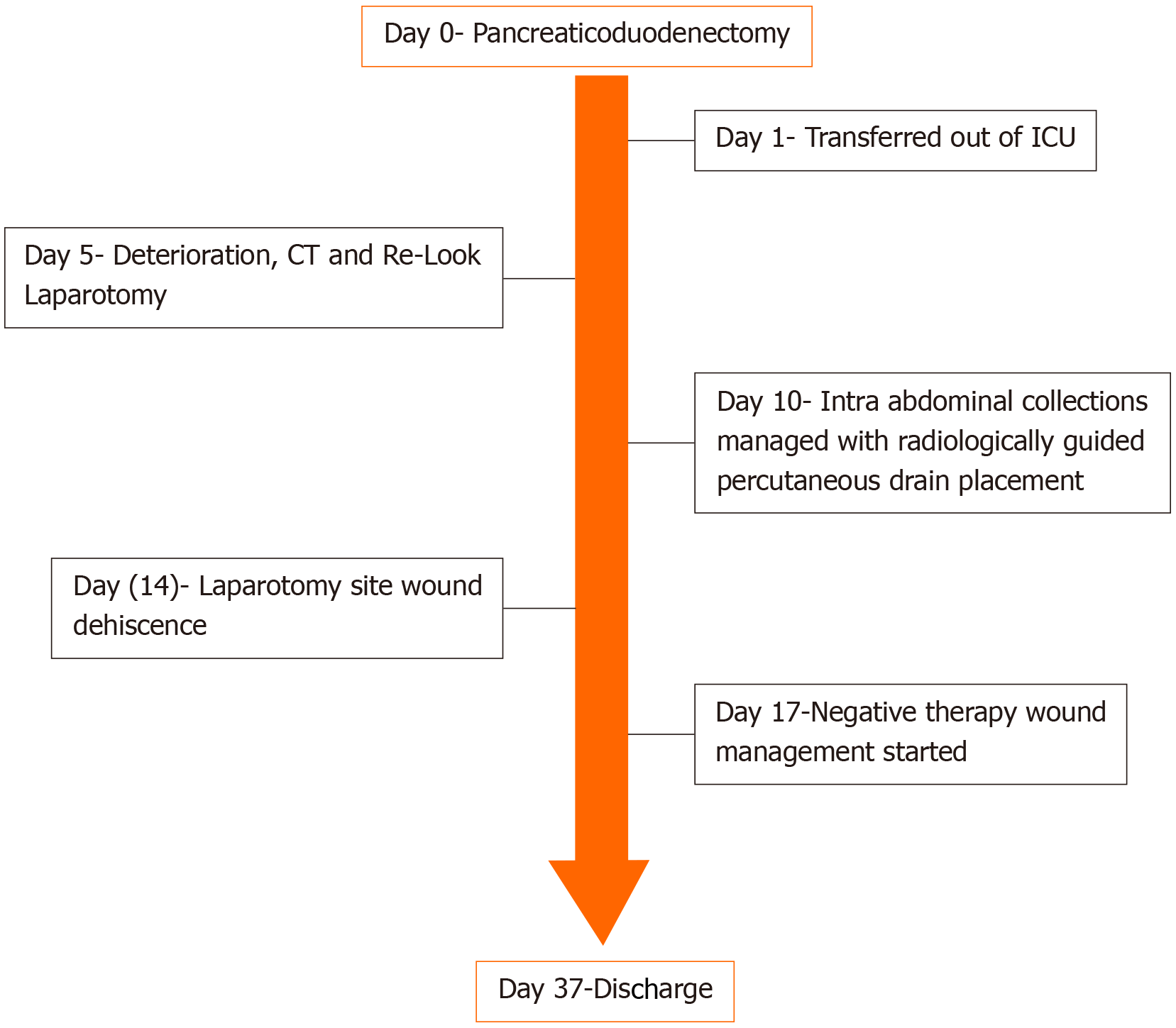

The patient was discharged to home on day 37 post-admission. Upon return home, she attended follow-up in the outpatient clinic. She has reported no ongoing issues since her discharge and has resumed full diet. A timeline of her care is outlined in Figure 4.

EN is a tried and tested method for the administration of cost-effective complete nutrition in the post-operative surgical patient, having been shown in the literature to reduce post-operative morbidity and mortality[3-5]. EN is favourable over TPN for the reasons previously outlined; it also has greater cost effectiveness and lower complication rate. Further, it is mostly well tolerated by the overall patient population[4-6]. Critically ill patients and those mechanically ventilated represent another cohort of patients that benefit from EN.

The two main routes of administration for EN are gastric and jejunal. EN administration to the small bowel distal to the pylorus has been shown in seven separate randomised control trials to reduce aspiration and regurgitation of feed and to maximise time between administration and absorption. As reported, there is no statistical difference in associated morbidity and mortality rates[7]. The main forms of EN administration to the jejunum are NJ feeding tube and a feeding jejunostomy tube. Both have their advantages and disadvantages, depending on the clinical situation. NJ tubes, in particular, are considered a temporary option, while feeding jejunostomy tubes have their own set of complications, as highlighted by Kitagawa et al[8] in 2019, where 17 of 100 patients suffered from small bowel obstruction secondary to malrotation related to the feeding tubes.

We performed a literature search of reports from 1966-2020 in the MEDLINE database. The following key words were entered: Gastrointestinal obstruction, EN, solidification, and bezoar. We identified eight articles describing a total of 14 cases of small bowel obstruction secondary to enteral feed bezoar. Among those 14 cases, all but 4 occurred after upper gastrointestinal surgery and most had an admission to an ICU. All but 1 case required further surgical intervention for deteriorating clinical picture. It is important to note that these publications are limited to case reports that are all retrospective; however, the themes, diagnosis and treatments are very similar throughout the published articles.

The first recorded incidence of enteral feed bezoar was published by O’Malley et al[9] in 1981. The authors described a single case report of a patient who had had a hemigastrecotmy, vagotomy and Bilroth II procedure to treat a bleeding ulcer. The patient had been receiving his EN through a jejunostomy. He required a second laparotomy for per rectal bleeding and fever, and was noted to have a 75 cm portion of small bowel with inspissated feed. He required resection and was discharged on day 13. It was postulated that intestinal dysmotility and opioid analgesia was the cause of this episode.

In 1990, McIvor et al[4] first suggested feed composition as a factor in enteral feed bezoar. Their case report described a patient with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura with hospital-acquired pneumonia. The patient was undergoing NG feeding, when on day 8 the patient was diagnosed with Ogilvie’s syndrome and underwent colonoscopic decompression. However, without improvement at 2 d later, they proceeded to laparotomy. Intraoperatively, a caecal bezoar was discovered. It had caused pressure necrosis and avulsion of the caecal pedicle, with the small bowel full of EN. The authors also hypothesized intestinal dysmotility, opioid medication and fibre bulk as causes for this episode.

In 1996, O’Neil et al[10] described the first and only non-operatively managed enteral feed bezoar. Their patient was 7 d out from a radical gastrectomy, when he developed high NG output volumes. Results from a barium meal were consistent with small bowel obstruction. Treatment with papain and normal saline was administered through the NG tube, along with intravenous hydration and bowel rest. Further contrast studies showed regression, and the patient was discharged on day 14.

After that, in 1999, Scaife et al[5] published a case series of 4 patients. It is notable that none of these patients had undergone gastrointestinal surgery. All 4 were patients who were admitted to the ICU after extensive burns and required NJ feeding after intubation. All 4 had presented with abdominal symptoms at approximately 2 wk into the admission. All had perforation of either small bowel or colon and inspissated feed throughout the gastrointestinal tract. Two of these patients had pressure necrosis injuries secondary to the bezoar.

In 2005, Halkic et al[1] reported a case of small bowel obstruction and perforation that occurred at 7 d after a pancreaticoduodenectomy. Intra-operatively, there was impacted enteral feed, with wall necrosis and perforation. The authors likened the causative factors to necrotizing enterocolitis, with hyperosmolarity, bacterial overgrowth and impaction of feed causing mucosal injury. This would have been directly complicated by local vessel vasospasm, ending in necrosis.

The next case series was published by Dedes et al[6] in 2006. The authors reported 3 cases after upper gastrointestinal operations. All were given EN in the post-operative period. In addition, all required a second laparotomy to address a mechanical obstruction secondary to the feed solidification. The authors hypothesized that the lack of stomach caused pH disturbance in the remaining gastrointestinal tract. That, along with opioid medication, may have allowed the fibre to precipitate out, causing a plug.

Bouwyn et al[11] next described a single case of enteral feed bezoar in 2011. Their case was a patient who had been intubated for pneumonia. However, his NG feed was interrupted on three separate occasions and replaced with TPN. At 6 wk after admission, the patient required a laparotomy for abdominal distension. Intra-operatively, there were sigmoid and small bowel perforations, faecal peritonitis, and multiple gastric and small bowel bezoars. The period of hospitalization to discharge was 4 mo. This case was the first reported in the literature of disseminated EN bezoar. The authors theorized that post-operative paralytic ileus in conjunction with opioid medication was the cause.

Finally, in 2018, Leonello et al[2] published a case report of 2 patients with this condition. Both had undergone upper gastrointestinal surgery during their admission and required a second laparotomy to address perforation. The obstruction and perforation were caused by EN solidification. The authors had proposed that neurohormonal changes due to the original surgery and use of bulking agents were the cause.

A summary of these 14 cases and their findings are provided in Table 1.

| Ref. | Year | Patient characteristics | Type of bezoar | Proposed mechanism | Outcome | |||

| Diagnosis on admission/surgery type, if any | Feeding tube location | Bezoar location | Treatment | |||||

| O’Malley et al[9] | 1981 | Bleeding ulcer/hemigastrectomy | Jejunum | Small bowel | Resection | Impacted feed | Opioid analgesia Intestinal dysmotility | D/C |

| McIvor et al[4] | 1990 | TTP | Stomach | Caecum | Resection | Impacted feed | Opioid analgesia; intestinal dysmotility; fibre bulk | D/C |

| O’Neil et al[10] | 1996 | Gastric cancer Radical gastrectomy | Jejunum | Small bowel | Papain | Unknown | Opioid analgesia (causing paralytic Ileus) | D/C |

| Scaife et al[5] | 1999 | Burns | Jejunum | Small Bowel/Caecum | Resection | Impacted feed | Bulking agents | D/C |

| Halkic et al[1] | 2005 | Pancreatic cancer Whipple’s procedure | Jejunum | Small bowel | Resection | Impacted feed | Hyperosmolarity; bacterial overgrowth | |

| Dedes et al[6] | 2006 | Gastric cancer Total gastrectomy | Stomach/jejunum | Small bowel | Enterotomy | Impacted feed | pH disturbance with no stomach, precipitation of fibres | D/C |

| Bouwyn et al[11] | 2011 | Pneumonia | Stomach | Small bowel | Resection | Multiple small bezoars | Opioid medication (causing paralytic ileus) | D/C |

| Leonello et al[2] | 2018 | Gastric/intestinal cancer UGI bleeding | Jejunum | Small bowel | Resection | Impacted feed | Neurohormonal changes; bulking agents | Death |

There are many postulated causes for this complication. Overall, these can be categorized into mechanical and systemic causes. The mechanical causes include anatomical changes, use of bulking agents, and EN composition. Anatomical changes resulting from gastric surgery are known to lead to neurohormonal function and pH changes[1,3,5,11], and such has been suggested to slow gastrointestinal transit and reduce absorption and digestion. With pancreatectomies, the surgery causes a reduction in pancreatic enzymes. Finally, in truncal vagotomies, the reduction in gastric motility and progression is thought to reduce small intestine digestion[4,6,9]. The use of bulking agents and the EN composition have both been indicated in the pathological thickening and solidification of EN[4].

Systemic causes include splanchnic hypoperfusion, dehydration, and pharmacological interventions. Splanchnic hypoperfusion is the most common, occurring either from reduced cardiac output or vasopressor use. It causes a reduction in gastric motility and reduced bicarbonate production[1,2]. Dehydration leads to reduced gastrointestinal tract secretions and a differing composition of EN. Ultimately, it causes pathological thickening.

Pharmacological interventions include sucralfate, morphine and its analogues, and finally medications that interfere with gastrointestinal tract pH (i.e. H2 receptor blockers, antacids). Sucralfates bind to the EN, causing insoluble complexes that in turn cause solidification[1,2]. Morphine analogues reduce gastrointestinal tract motility, thereby increasing the likelihood of pathological thickening[1-3,6].

Surgical management is the mainstay of treatment for intestinal and colonic bezoar. All but 1 patient in the literature required operative intervention in the form of a laparotomy. Surgical management itself has been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality[4]. Most patients have had their EN stopped and TPN commenced. This contrasts with oesophageal bezoar, which has been managed both medically and endoscopically. The findings at the time of surgery have been perforation and obstruction. Of note, this has been consistent across the literature. In the majority of cases, the EN showed thickening and in 2 cases, the feed appeared to have become a cast in the bowel[6,11].

It is interesting to note that our case had similarities with the others in the literature. Our patient had undergone a pancreaticoduodenectomy. As we have previously mentioned, this is the second such occurrence published. Thus, a potential cause was the reduction in pancreatic enzymes[1]. Also, she had been in the ICU and initially had been prescribed a morphine analogue and bulking agents. All of the above have been previously postulated as causes for this condition[2,4]. Most likely, there is no single cause and our case represents a multifactorial nature for the cause of bezoar formation.

Enteral feed bezoar is an uncommon but life-threatening complication of enteral feeding. It can occur in the post-operative surgical patient and critically ill ICU patient. The majority of these patients present with vague abdominal symptoms, deteriorating to septic shock. The management of this condition is usually an exploratory laparotomy and removal of thickened feed. Bowel resection is also required to address necrotic bowel. Operative findings commonly include thickened or inspissated feed, perforation, and necrosis. Given the nature of the presentation, a high clinical suspicion and low threshold for return to theatre is advised. This is especially relevant in the deteriorating patient, to reduce the chance of bowel resection.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Australia

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chawla S, Serban ED S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Halkic N, Guerid S, Blanchard A, Gintzburger D, Matter M. Small-bowel perforation: a consequence of feeding jejunostomy. Can J Surg. 2005;48:161-162. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Leonello G, Rizzo AG, Di Dio V, Soriano A, Previti C, Pantè GG, Mastrojeni C, Pantè S. Gastrointestinal obstruction caused by solidification and coagulation of enteral nutrition: pathogenetic mechanisms and potential risk factors. Int Med Case Rep J. 2018;11:81-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Luttikhold J vNK, Buijs N, Rijina H, van Leeuwen PAM. Gastrointestinal obstruction by solidification of enteral nutrition: a result of impaired digestion in critically ill patients. Nutr Ther Metab. 2013;31:101-109. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | McIvor AC, Meguid MM, Curtas S, Warren J, Kaplan DS. Intestinal obstruction from cecal bezoar; a complication of fiber-containing tube feedings. Nutrition. 1990;6:115-117. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Scaife CL, Saffle JR, Morris SE. Intestinal obstruction secondary to enteral feedings in burn trauma patients. J Trauma. 1999;47:859-863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Dedes KJ, Schiesser M, Schäfer M, Clavien PA. Postoperative bezoar ileus after early enteral feeding. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:123-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Heyland DK, Drover JW, Dhaliwal R, Greenwood J. Optimizing the benefits and minimizing the risks of enteral nutrition in the critically ill: role of small bowel feeding. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2002;26:S51-5; discussion S56-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kitagawa H, Namikawa T, Iwabu J, Uemura S, Munekage M, Yokota K, Kobayashi M, Hanazaki K. Bowel obstruction associated with a feeding jejunostomy and its association to weight loss after thoracoscopic esophagectomy. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;19:104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | O'Malley JA, Ferrucci JT, Goodgame JT. Medication bezoar: intestinal obstruction by an isocal bezoar. Case report and review of the literature. Gastrointest Radiol. 1981;6:141-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | O'Neil HK, Hibbein JF, Resnick DJ, Bass EM, Aizenstein RI. Intestinal obstruction by a bezoar from tube feedings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167:1477-1478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bouwyn JP, Clavier T, Eraldi JP, Bougerol F, Rigaud JP, Auriant I, Devos N. Diffuse digestive bezoar: a rare and severe complication of enteral nutrition in the intensive care unit (ICU). Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:730-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |