INTRODUCTION

The term “groin hernia” was first used by Stoppa and Fruchaud during the early 1950s[1]. Hernias in the groin include indirect inguinal, direct inguinal, and femoral hernias[2]. Obturator and supravesical hernias anatomically appear very close to the groin[2]. We therefore focus on indirect inguinal, direct inguinal, femoral, obturator, and supravesical hernias as groin hernias. Herniorrhaphy had been performed to repair inguinal and femoral hernias since the eighteenth century. Basssini devised and reported a more modern herniorrhaphy[3,4], and thereafter groin herniorrhaphy became the most common surgery performed[2]. With the addition of mesh, Lichtenstein established the concept of a “tension-free repair” (TFR)[5,6], a technique now categorized as “hernioplasty”. To date, many physicians have focused on the preperitoneal (posterior) space (PPS)[1,7-16], myopectineal orifice (MO)[1,2,17-20], topographic nerves[21-30], and regional vessels[2,31-33].

Currently, laparoscopy and endoscopy have therapeutic potential for improving these procedures. Although international guidelines for groin hernia management are documented[34,35], some physicians may not believe that definitive criteria for selecting these surgical procedures have been established. In fact, the physician’s preferences, the technique’s commercial basis, or its cost-effectiveness may be the underlying reasoning for choosing the technique, which then goes unchallenged. Laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) repair seems to be a powerful technique for adult patients[34], even though general anesthesia is required[36,37].

Both technical skill and anatomical familiarity are important for ensuring safe, reliable surgery. Here, we focus on laparoscopic TAPP repair in adult patients and review previous reports regarding the anatomy of groin hernias and the surgical techniques required for TAPP repair. Using illustrations and schemas, we summarize the current knowledge of anatomy that is important for successful TAPP repair, clarify the knacks and pitfalls during surgery, and discuss debatable points.

LAYERS

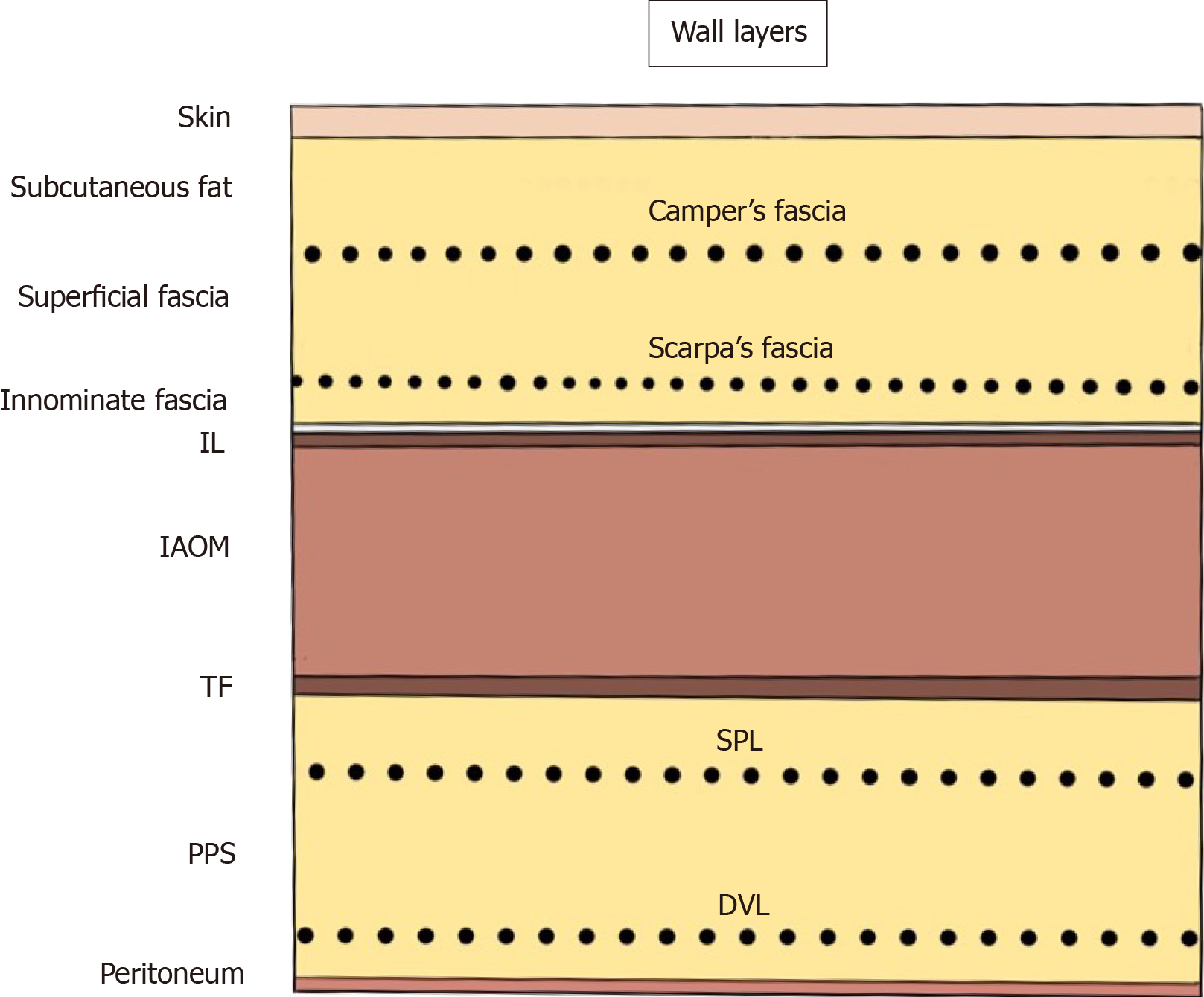

The abdominal wall at the groin is classically identified as the “nine layers”[38]. These layers consist of the skin; subcutaneous fat; superficial fasciae (Camper’s and Scarpa’s fasciae); innominate (untitled) fascia, which is a thin membrane on the inguinal ligament; the inguinal ligament (IL) itself; internal abdominal oblique muscle (AOM); transversalis fascia (TF); preperitoneal space (PPS), including the superficial parietal layer (SPL) and the deep visceral layer (DVL); and the peritoneum. Familiarity with the anatomy of the SPL and DVL in the PPS is especially important for successful TAPP repair (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Abdominal wall at the groin.

The nine layers include the skin, subcutaneous fat, superficial fasciae (Camper’s and Scarpa’s fasciae), innominate (untitled) fascia, inguinal ligament, internal abdominal oblique muscle, transversalis fascia, preperitoneal space [superficial parietal layer (anterior subperitoneal fascia) and deeper visceral layer (posterior subperitoneal fascia)] and peritoneum. DVL: Deeper visceral layer; IAOM: Internal abdominal oblique muscle; IL: Inguinal ligament; PPS: Preperitoneal space; SPL: Superficial parietal layer; TF: Transversalis fascia.

PPS AND MO

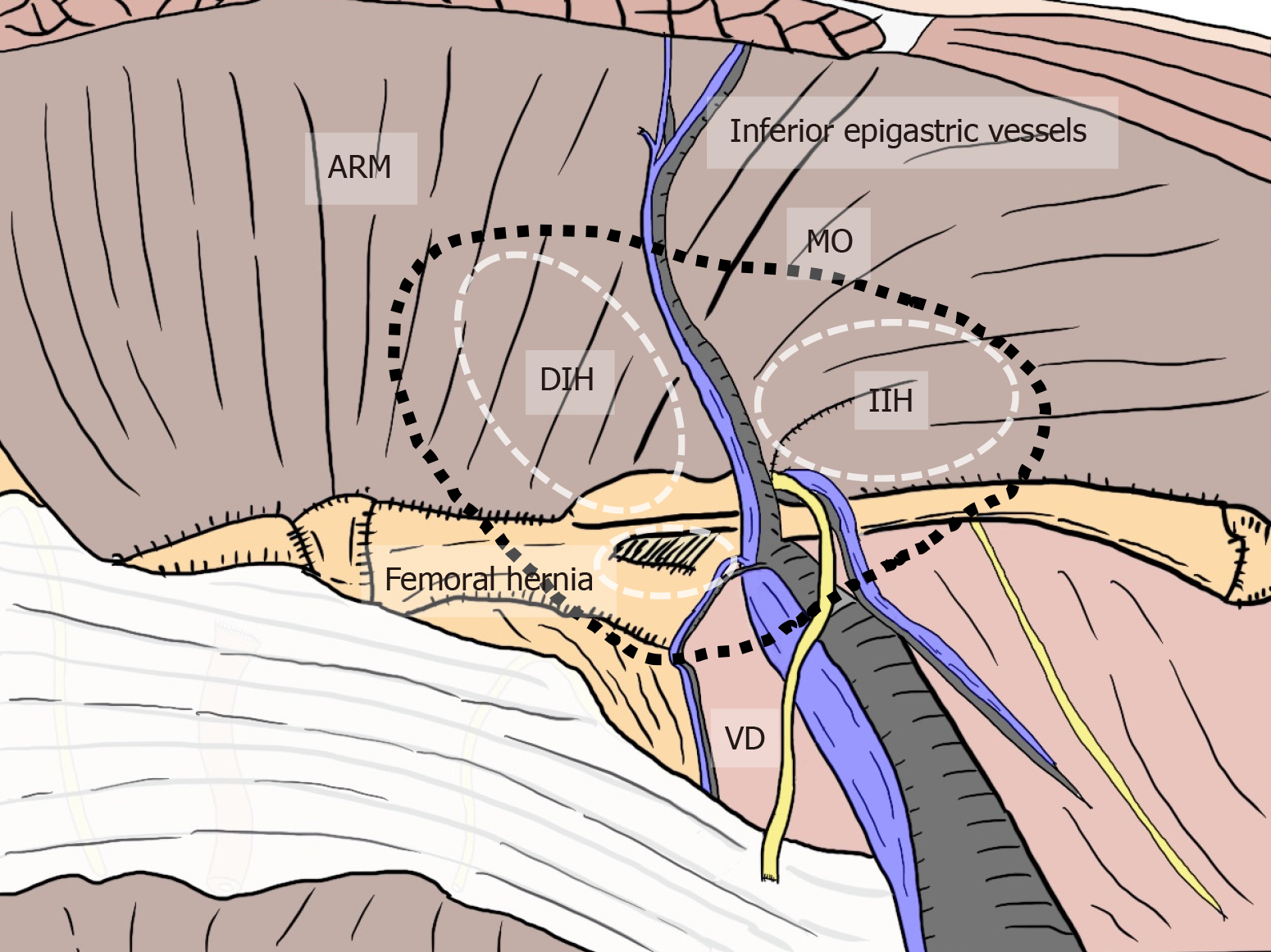

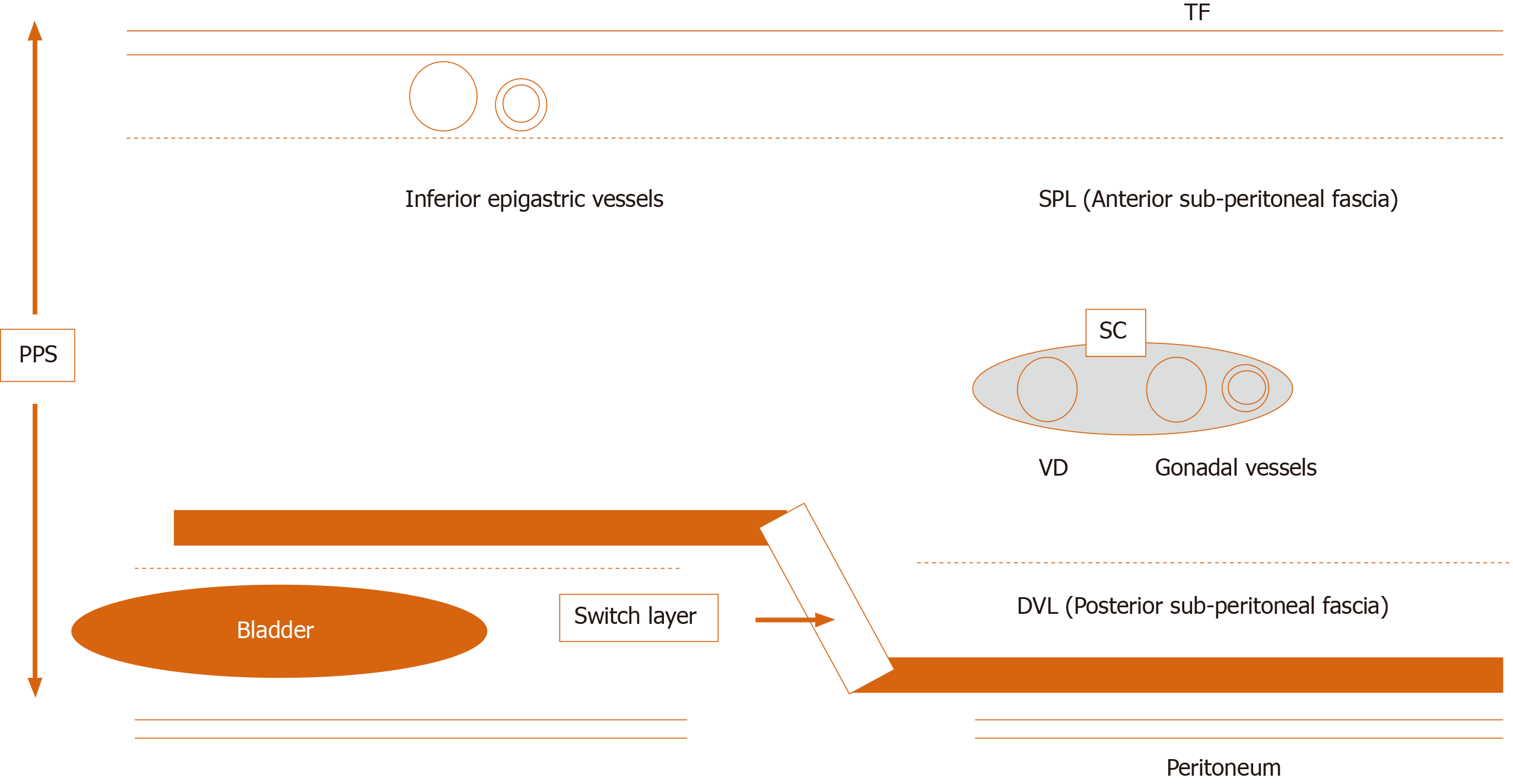

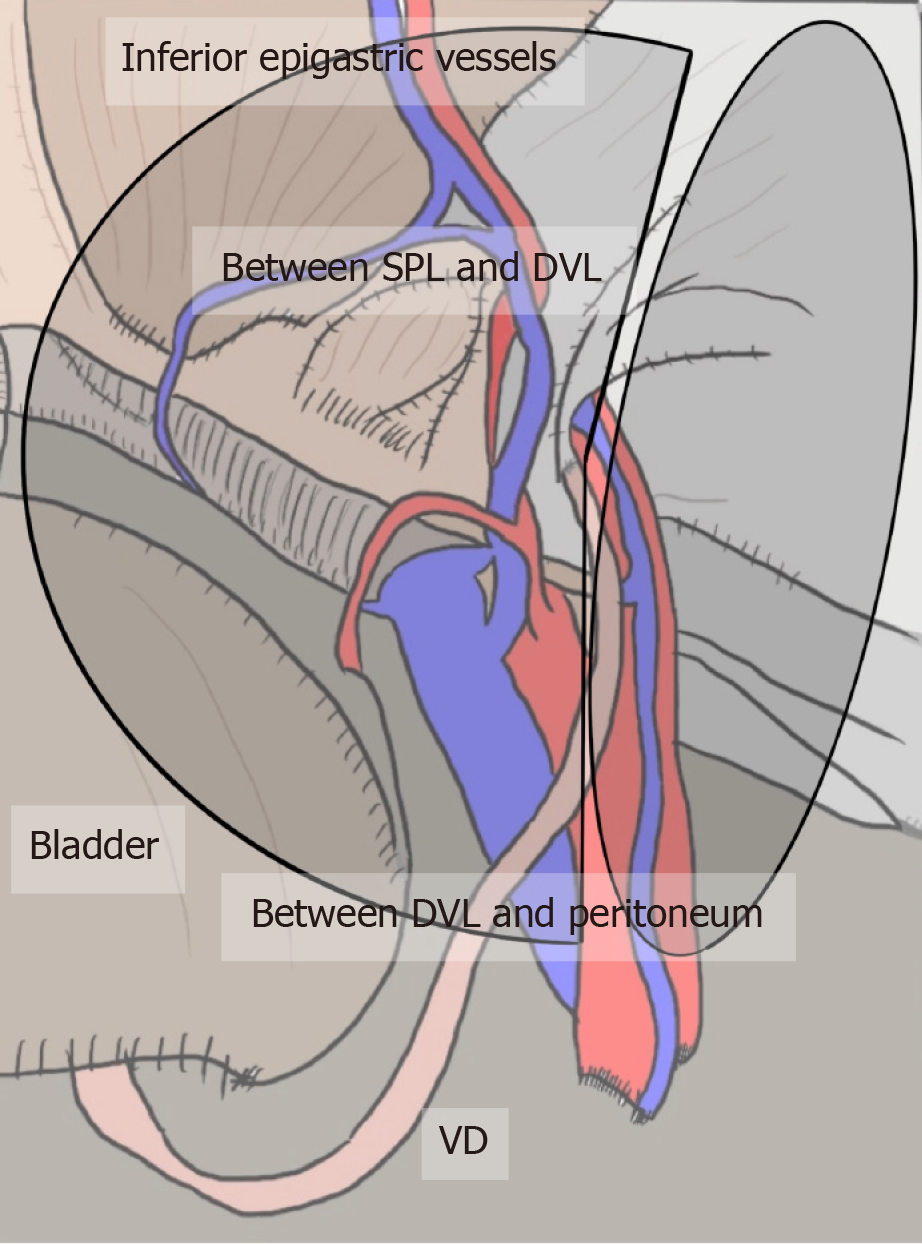

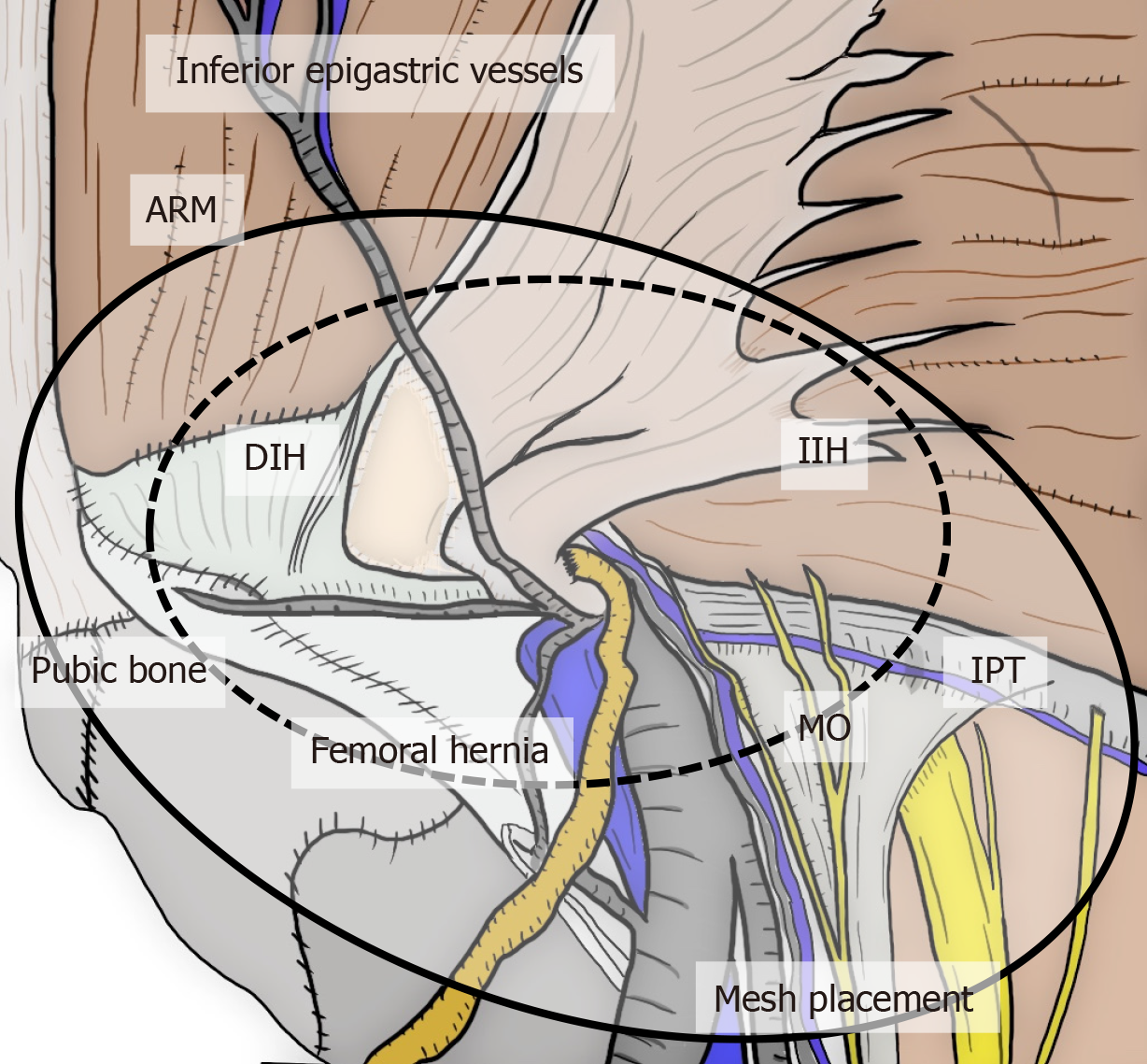

All hernias at the groin result from a defect of the TF and pass through an MO[1,2] (Figure 2). The importance of an “underlay” (inlay) patch placed between the TF and peritoneum is widely recognized, and general surgeons commonly accept the concept of optimal repair at the PPS[18-20], although an “onlay patch”, placed at the anterior side of the TF, has been used in the past. The PPS is observed between the TF and peritoneum. Adequate creation of an extended PPS is important for optimal outcomes[39,40]. Some early physicians mentioned this important space[1,7-16]. In particular, recognition of the SPL and DVL was a milestone for further developments in these surgical repairs[41]. The SPL is comprised of anterior subperitoneal fascia and the DVL of posterior subperitoneal fascia[27]. Some physicians investigated in detail the layer where the bladder exists[14,16,42] (Figure 3). Adequate surgical mesh should be placed in an appropriate layer to avoid hernia recurrence and bladder injury (Figure 4).

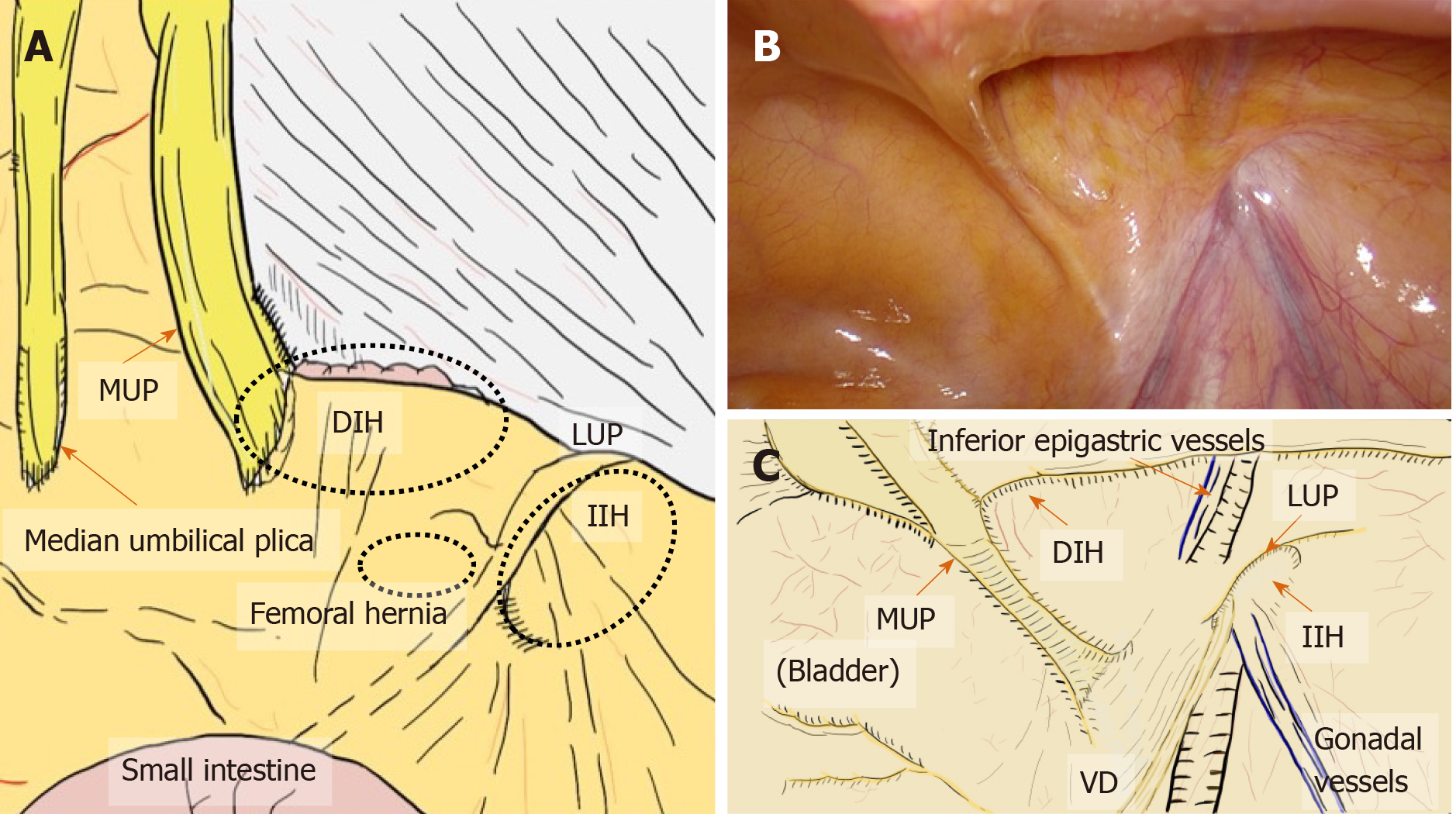

Figure 2 Relation between myopectineal orifice and all hernias (direct inguinal hernia, indirect inguinal hernia, femoral hernia) at the groin.

The oval myopectineal orifice (black dotted circle) is the origin of all groin hernias (white dotted circles). ARM: Abdominal rectal muscle; DIH: Direct inguinal hernia; IIH: Indirect inguinal hernia; MO: Myopectineal orifice; VD: Vas deferens.

Figure 3 Current knowledge of the preperitoneal space and the adequate position of mesh placement during the transabdominal preperitoneal repair.

Anatomical identification of the superficial parietal layer (SPL) and deeper visceral layer (DVL) was a milestone for further developments in surgical repairs. The dissected layer should be adequately switched between the SPL and DVL. DVL: Deeper visceral layer; PPS: Preperitoneal space; SC: Spermatic cord; SPL: Superficial parietal layer; TAPP: Transabdominal preperitoneal; TF: Transversalis fascia; VD: Vas deferens.

Figure 4 Appropriate layer and adequate mesh placement during a transabdominal preperitoneal repair.

Surgical mesh should be adequately placed in an appropriate layer to avoid hernia recurrence and bladder injury. The layer is dissected between the superficial parietal layer and deeper visceral layer (DVL) on the inner side, whereas it is dissected between the DVL and peritoneum on the outer side. DVL: Deeper visceral layer; SPL: Superficial parietal layer; VD: Vas deferens.

Laparoscopic exploration easily reveals the MO. Anatomical familiarity with this orifice[2] is crucial for reliable treatment[18-20]. Full coverage of the MO creates the optimal condition[18-20]. According to the TFR concept, the orifice should be fully reinforced to prevent recurrence of all indirect and direct inguinal hernias as well as femoral hernias[18-20].

PLICAE AND FOSSA

Hernia presentation can be more easily evaluated on a laparoscopic view than on an endoscopic or anterior view[2,33] (Figure 5). The initial laparoscopic view of the groin identifies five plicae (perineal folds), which serve as guidance landmarks[2,33]. The median umbilical plica observed in the midline contains the obliterated urachus, which has little clinical relevance for this surgical repair[2,33]. In contrast, the medial umbilical plica (MUP) is the most prominent landmark seen on the initial view[2,33]. It is easily recognized and contains remnant umbilical vessels[2,33]. The MUP should not be routinely cut because the umbilical vessels may still be patent, which would result in bleeding[2,33]. Although the lateral umbilical plica (LUP) may be difficult to identify based on the body habitus and fat distribution, its identification is most important[2,33]. The LUP contains the inferior epigastric vessels, which divide the groin into a medial compartment (space of Retzius) and a lateral compartment (space of Bogros)[2,33]. External palpation of the surface anatomy allows precise localization of the anterosuperior iliac spine and pubic tubercle, thereby delineating the iliopubic tract (IPT), which divides the groin into the upper and (most critical) lower parts[2,33]. Briefly, the space of Bogros extends laterally from the space of Retzius toward the anterosuperior iliac spine[2]. These spaces must be developed to allow adequate room for the hernia repair and mesh placement[2].

Figure 5 Laparoscopic view at the groin.

A: Laparoscopic view focused on the relation between the plicae and the hernial defect. B and C: The actual view (B) and schema (C) are shown. Laparoscopic view with pneumoperitoneum has a significant advantage for easy, accurate diagnosis without any missed evaluations because the plicae and fossae precisely indicate hernia defects. DIH: Direct inguinal hernia; IIH: Indirect inguinal hernia; MUP: Medial umbilical plica; LUP: Lateral umbilical plica; VD: Vas deferens.

The plicae make three flat fossae recognizable on each side, corresponding to possible hernial defects[2,33]. The lateral fossa, in the triangle between the LUP and IPT, corresponds to the location of the internal (deep) inguinal ring (IIR) from which an indirect (external or lateral) inguinal hernia originates[2,33]. The medial fossa, located between the LUP and MUP, is limited inferiorly by the IPT[2,33]. A direct (internal or inner) inguinal hernia is found in this region as it passes through Hesselbach’s triangle[2,33]. The supravesical fossa is located medial to the MUP and cranial to the IPT, pubic bone, and urinary bladder[2,33]. This weak point is rarely the origin of a supravesical hernia[2,33], which may be classified as an internal or external supravesical hernia based on its pathway. Femoral hernias develop within the region of the femoral canal (the triangle below the IPT, which is medial to the femoral vein and superior to the pubic bone and Cooper’s ligament)[2,33].

CURRENT SURGERY USING LAPAROSCOPY OR ENDOSCOPY

In accord with the TFR concept, prosthetic mesh has been used routinely since the latter half of the twentieth century, at which time surgeons began to recognize the importance of the PPS. Laparoscopy and endoscopy thus have therapeutic potential in the surgical setting.

Laparoscopic TAPP repair is based on the same principle as the technique reported by Tait’s group in 1891[43]. That is, pneumoperitoneum is established, peritoneal flaps are created, anatomical landmarks are identified, and the hernial sac is dissected. The mesh is then deployed and anchored, after which the peritoneum is closed after confirming mesh fixation. Fletcher first employed a laparoscope to repair a groin hernia in 1979, laparoscopically closing the neck of the hernial sac[44]. In 1982, Gel performed laparoscopic hernia repair by simply closing the peritoneal opening with staples—without dissection, ligation, or reduction of the sac[45]. In 1989, Bogojavalensky revived this procedure with a mesh plug[46]. Schultz et al[47] plugged the IL with polypropylene mesh and published the first series on laparoscopic surgery in 1990. Arregui et al[48,49] described the transabdominal preperitoneal technique in 1992 and 1993.

The endoscopic totally extraperitoneal (TEP) repair depends on the preperitoneal anatomy, which was clarified by Stoppa and Fruchaud in 1956[1]. The PPS is extended by the pneumo-preperitoneum (pneumoperitoneum established in the PPS), after which the inguinal sac could be identified. The mesh is then deployed and anchored. Dulucq first reported mesh implantation into the PPS in 1991[50], which was followed by the reports of Ferzli et al[51] in 1992, Himpens in 1992[52], and McKernan and Laws in 1993[53]. Phillips et al[54] documented the TEP procedure in 1993.

Laparoscopic intraperitoneal onlay mesh repair does not involve dissection of the groin. Toy and Smoot documented this procedure in 1991[55], and the Fitzgibbons group used it initially that same year[56].

There are many therapeutic options in the approach (i.e., open vs laparoscopic/ endoscopic, anterior vs preperitoneal), the plane where the mesh is placed (i.e., the layer in front of the TF vs the PPS), and the fixation device (i.e., sutures, sutureless, tacks, glue). There is also a wide range of prostheses (e.g., soft vs hard mesh, sheeted vs three-dimensional mesh)[57].

COMPARISON OF TAPP AND TEP REPAIRS

TAPP and TEP repairs have advantages and disadvantages[2]. Briefly, TEP repair (i.e., endoscopic approach) causes less pain, is associated with fewer intraperitoneal complications, and is technically less difficult[2]. TAPP repair (i.e., laparoscopic approach) offers a better view of the anatomy and similar laparoscopic equipment across manufacturers, but it is more costly[2,58].

TAPP offers the advantages of accurate diagnoses[2,33], repair of bilateral and recurrent hernias[2], less postoperative pain[2], early recovery allowing work and activities[2], TFR of the PPS[2], ability to cover obturator hernias[59], and avoidance of potential injury to the spermatic cord (SC)[2]. The disadvantages of TAPP are the need for general anesthesia[2,36,37], adhering to a learning curve[2], higher cost[60], unexpected complications related to abdominal organs[60,61], adhesion to the mesh[2,61], unexpected injuries to vessels[2], prolonged operative time[60] and port-site hernia[2]. A concern of current advanced surgeries (e.g., TAPP and TEP) is as-yet-unknown long-term outcomes[62].

MESH MATERIAL

Many mesh types are currently available[63]. Hernia repair with mesh is called hernioplasty, whereas traditional repairs without mesh are called herniorrhaphy. The TFR concept, devised by Lichtenstein, was a breakthrough idea[5,6,40], with the addition of surgical mesh proving to be superior to other techniques[64]. Mesh, however, is inherently a foreign body, and postoperative removal may be required for some reasons (e.g., refractory infection)[65]. Biological mesh is currently available that has biocompatibility superior to that of other meshes. Hence, it does not trigger an inflammatory response in the body, although higher cost has hampered its wide acceptance[63]. Nevertheless, although the cost is high[63,66,67], only biological mesh can resolve critical problems associated with synthetic mesh (e.g., female agenesis, male sterility, neuropathy, chronic pain)[68,69]. To date, we are still awaiting a less expensive biological mesh that has been developed with ethical responsibility.

RECURRENT HERNIAS

Postoperative hernia recurrence is a critical issue[70,71]. Especially for recurrent hernias, the type of repair chosen seems to depend on the surgeon’s assessment of what is appropriate for that particular case and patient. Thus, the decision is made on a case-by-case basis — i.e., an “anything-goes” situation. The optimal procedure, however, should be chosen based on the primary surgery. TAPP repair by a skilled laparoscopic surgeon is clearly recommended as the first choice, especially for recurrent hernias after conventional open repair[71,72]. The laparoscopic view allows surgeons to not only diagnose the recurrent hernia accurately with some ease but also to repair it from an intact, untouched dissection plane. Clinical results of the TAPP repair for recurrent hernias has been well investigated, and excellent outcomes have been documented[71,73,74]. TAPP repair is also useful for supravesical hernias (e.g., inguinal bladder hernia)[75]. Paradoxically, a failed TAPP may cause a bladder hernia in the suprapubic area[76].

OBTURATOR HERNIAS

Obturator hernias are internal herniations through the obturator foramen, bordered by the obturator vessels and nerve[77]. An obturator hernia should be considered bilateral disease[78]. Hence, unilateral repair may not be sufficient[79,80]. The normal diameter of the obturator foramen is approximately 1.0 cm[81]. The bilateral obturator foramina should be routinely checked intraoperatively as bilateral repairs are required even if there is only subtle dilation of the opposite side of the obturator foramen.

TAPP repair is advantageous in that the bilateral obturator foramina is easily checked[2] and obturator hernias fully covered if necessary[59]. Surgical procedures in the reverse direction, however, are technically difficult. Preperitoneal placement of surgical mesh in the direction of the obturator foramina may be possible during a TAPP repair, with the peritoneum closed to avoid contact with the mesh.

AGENESIS

Postoperative agenesis is a critical issue. Especially in boys and men, both the surgical technique and the mesh material have an impact on the integrity of the SC and on testicular function[82-84]. Contact with mesh material may cause sterility in male patients[85]. Mesh inherently causes postoperative atrophy of varying degrees, so biomechanical stability is important[86]. Soft and hard meshes may result in unidirectional or matrix-like atrophy[63,87,88]. Biological mesh will likely be a powerful tool in the near future, although the cost is still high[63,66,67]. Testicular necrosis induces the action of autoimmune antibody against the patient’s own sperm[89], subsequently causing male sterility[90].

NEUROPATHY

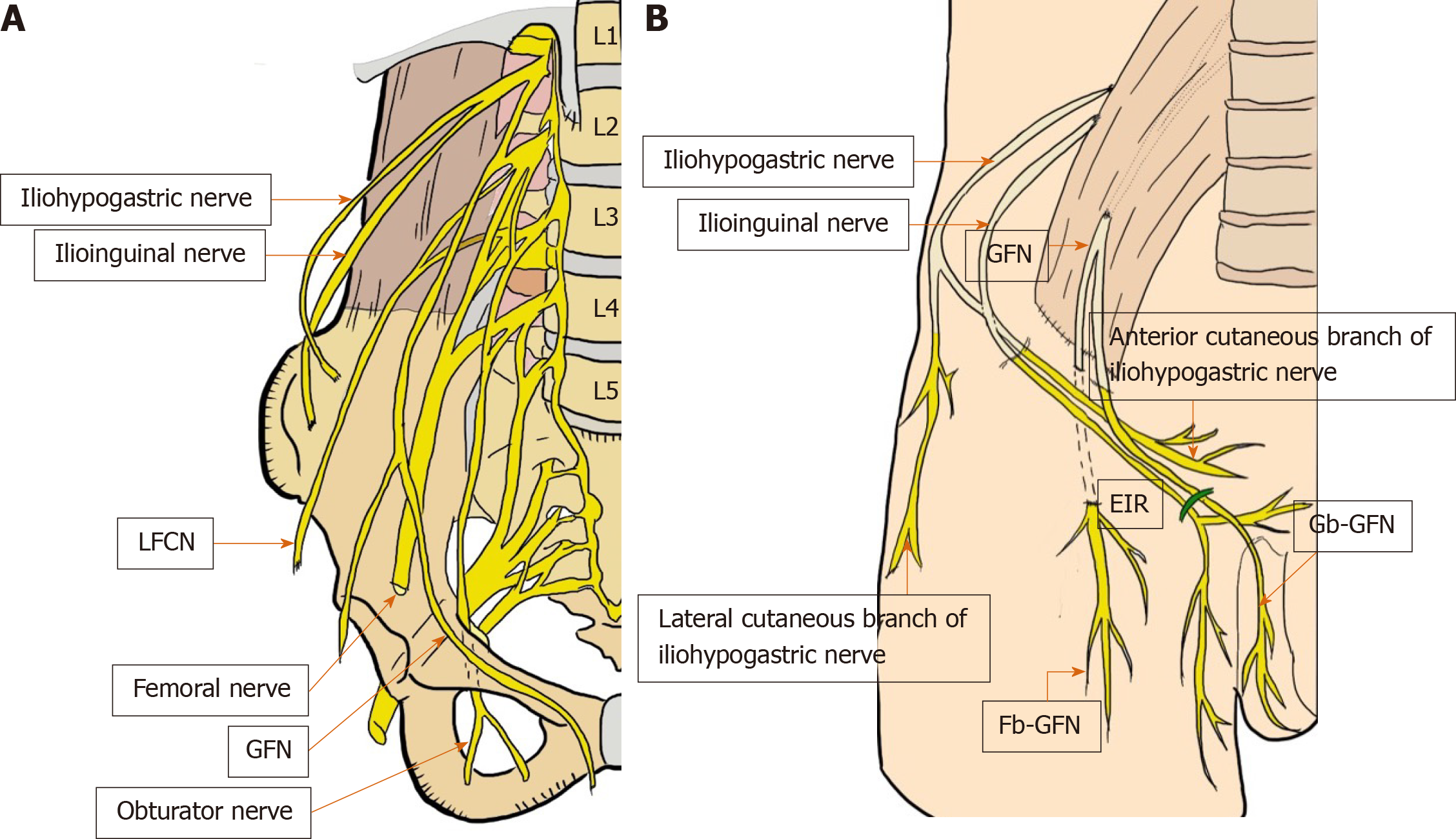

Precise knowledge of the topography of the nerves in this anatomical area is essential for performing a high-quality repair with optimal patient outcomes[2,21-30,33]. Although the incidence of postoperative pain and/or discomfort was reportedly approximately 15%[33,91], anatomical ignorance and thoughtless procedures could result in poor outcomes with refractory neuropathy and intractable chronic pain[2,21-30,33]. There have been extensive reports describing the anatomy of the nerves located in the groin[21-30]. Overall, only six nerves—iliohypogastric nerve, ilioinguinal nerve, femoral nerve, genitofemoral nerve (genital and femoral branches), lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN), obturator nerve — are of interest in the field of groin hernias[2,21-30,33] (Figure 6A and B).

Figure 6 Critical nerves distributed in the field of the groin (A and B).

These six nerves of interest are the iliohypogastric nerve, ilioinguinal nerve, femoral nerve (including the anterior cutaneous branch), genitofemoral nerve (femoral and genital branches), lateral femoral cutaneous nerve of the thigh, and obturator nerve. EIR: External inguinal ring; Fb-GFN: The femoral branch of the GFN; Gb-GFN: Genital branch of the GFN; GFN: Genitofemoral nerve; LFCN: Lateral femoral cutaneous nerve.

Anatomically, some nerves are not directly involved in the dissection and repair planes utilized during hernia repair[33]. Nerves that typically exit the retroperitoneum and enter the anterior abdominal wall and inguinal canal (IC) may not be skeletonized during TAPP repairs[33]. Moreover, as a rule, there is great variability in the lumbar plexus neuroanatomy, especially when progressing distally along branches from the spinal origin[25,33].

The femoral nerve is usually well protected by the psoas tendon, surrounding fat and lymphatic tissue, and the spermatic sheath or iliac fascia. Hence, femoral nerve injury during surgery is rare[33]. Also, intraoperative injury of the obturator nerve is anecdotal because the nerve is well hidden[33].

Although the genitofemoral nerves run to the lower limbs, the more common injuries, unfortunately, are seen in the genitofemoral nerve (GFN) and LFCN[2,33] (Figure 7). The risks of intraoperative injuries have been estimated at approximately 80% in the LFCN, approximately 30% in the femoral branch of the genitofemoral nerve (Fb-GFN), and approximately 5% in the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve (Gb-GFN)[34]. Although the frequency is not more than 0.3%[92,93], each of these serious injuries has disastrous consequences for the patient, including intractable pain[33].

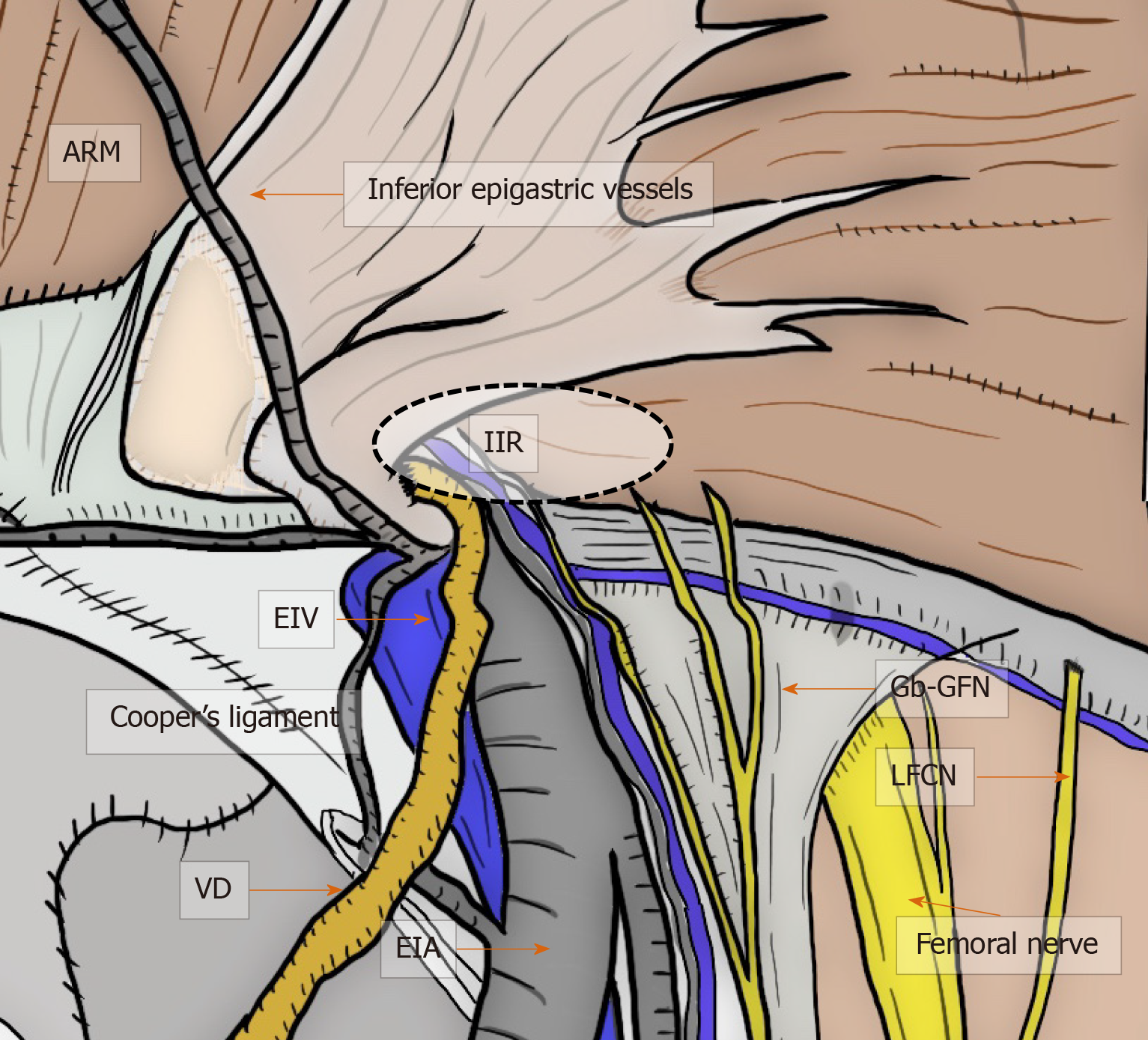

Figure 7 Critical nerves and other structures.

Laparoscopic view in the groin area focused on the relation between the critical nerves [especially genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve and lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN)] and the other structures. Although the genitofemoral nerves run to the lower limbs, the more common nerve injuries are unfortunately to the genitofemoral nerve and LFCN. Each of these serious injuries has disastrous consequences for the patient with intractable pain. ARM: Abdominal rectal muscle; EIA: External iliac artery; EIV: External iliac vein; Gb-GFN: Genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve; IIR: Indirect inguinal ring; LFCN: Lateral femoral cutaneous nerve; VD: Vas deferens.

The LFCN arises from the dorsal divisions of the second and third lumbar nerves[2,33]. The anterior branch divides into further branches that are distributed to the skin of the anterior and lateral parts of the thigh, reaching as far as the knee[2,33]. The posterior branch supplies the skin from the level of the greater trochanter to the middle of the thigh[2,33]. General surgeons should be aware that the LFCN typically crosses the middle of the surgical field during TAPP, although multiple nerve trunks may be identified[2,33].

The GFN arises from the first and second lumbar spines[2,33], passes downward, and emerges from the anterior surface of the psoas muscle[2,33]. The nerve continues on the surface of the psoas muscle, progressing caudally toward the IC and divides into two branches (i.e., Gb-GFN and Fb-GFN)[2,33]. The Gb-GFN continues downward (supplying the scrotal skin), accompanying the round ligament (supplying the pubic mound and labia major in female patients). General surgeons should understand the wide variation during the course of this nerve. In contrast to what has been described in classic papers, the Gb-GFN runs through the IC in only 14% of cases. Multiple branches have been observed in 44% of cases, and the nerve perforates the abdominal wall through the IIR and IPT in 49% of cases[25]. The Fb-GFN passes underneath the IL and IPT, traveling adjacent to the external iliac artery (EIA). It supplies the skin of the upper and anterior thighs[2,33]. Multiple branches, observed in 58% of cases, perforated the abdominal wall through the IPT with a wide variation in 73% of cases[25]. This nerve rarely runs near the anterosuperior iliac spine or through the IC[25]. Wide variations in the number and course of sensory nerves that traverse the PPS creates significant potential for overlap with the Gb-GFN, Fb-GFN, LFCN[2,33], and even the ilioinguinal nerve, with a wide area in which injury can occur[2,33]. Respecting these dissection planes and understanding the neuroanatomy minimizes contact and risk[2,33].

Nerve preservation during surgery requires a well-considered approach[2,33,94]. Even subtle factors during surgery (e.g., skeletonization, direct detection, counter-traction, mesh contact) could cause postoperative neuropathy and chronic pain[33,94-96]. Unnecessary procedures for nerve identification should be avoided as much as possible, and anatomical knowledge of the pathways of each nerve without direct explosion and complete skeletonization should be enough during surgery[2,33,94].

Although the courses of the obturator and femoral motor nerves are largely predictable and constant, the courses of the sensory nerves (e.g., GFN and LFCN) show great variability, with refractory symptoms[33]. Injury of the iliohypogastric nerve results in postoperative neuralgia and muscular atrophy[97]. Ilioinguinal nerve injury may cause intractable neuropathy[2,33].

SIGNATURE TRIANGLES

Important nerves on the lateral side of the IIR run from the interior pelvis to the thigh, which is considered the IPT[2,33]. In contrast, the most important vessels run on the internal side of the IIR[2,33].

The VD travels downward, crossing the iliac vessels medially[2,33]. Hence, the VD runs as the preperitoneal loop in the DVL[2,33]. Note that injury of the SC or VD results in refractory pain with burning[98].

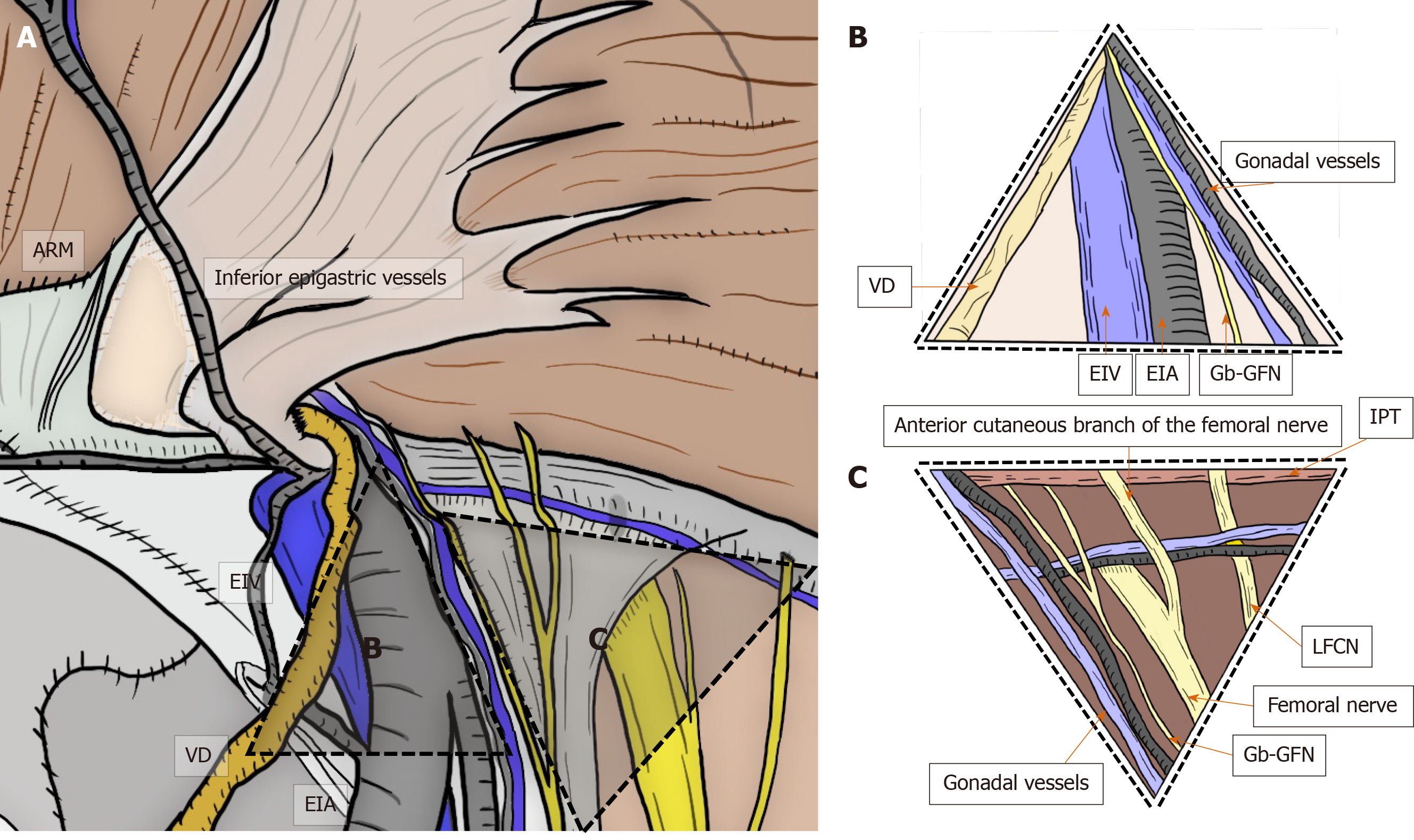

The basic anatomical principles of the laparoscopic view were first described by Spaw and Spaw in 1991 based on human cadaveric dissection[99]. They coined the term “triangle of doom” for the region between the VD and spermatic vessels. However, neuroanatomy in the PPS was not considered[99]. Thereafter, Rosser was the first to describe inguinal neuroanatomy in 1994, roughly delineating the anatomical course of the inguinal nerves[21]. Seid and Amos provided a more precise description of the nerves[22] and postulated that the triangle of doom should be extended farther laterally to the anterosuperior iliac spine. Currently, the triangle of doom is shown as an inverted V-shaped area bound laterally by the gonadal vessels and medially by the VD in male individuals and by the round ligament in female individuals[2,31-33]. The EIA, external iliac vein, deep circumflex iliac vein, Gb-GFN, and femoral nerve are all in this area[2,31-33] (Figure 8).

Figure 8 Triangle of doom and triangle of pain.

Triangle of doom and triangle of pain should be adequately recognized by the surgeon. Triangle of doom is an inverted V-shaped area bound laterally by the gonadal vessels and medially by the vas deferens in male patients, or the round ligament in female patients. The EIA, external iliac vein, deep circumflex iliac vein, genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve, and femoral nerve are involved in this area. Area of the triangle of pain involves the femoral branch of the genitofemoral nerve, lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, femoral nerve, and the anterior cutaneous branch of the femoral nerve. Even a subtle injury to the nerves located within the triangle of pain is a risk factor for intractable pain. ARM: Abdominal rectal muscle; EIA: External iliac artery; EIV: External iliac vein; Gb-GFN: Genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve; IPT: Iliopubic tract; LFCN: Lateral femoral cutaneous nerve; VD: Vas deferens.

In 1993, the most comprehensive analysis of inguinal neuroanatomy was performed by Annibali et al[23,24], who defined the “triangle of pain” as the area lateral to the testicular vessels and inferior to the IPT. Bittner used the term “trapezoid of disaster” for this area[33]. Recently, the course of the nerves and their variations were described in detail[25-27]. The area of the triangle of pain involved the Fb-GFN, LFCN, femoral nerve, and anterior cutaneous branch of the femoral nerve[2,31-33]. Even a subtle injury of nerves located within the triangle of pain was considered a risk for intractable pain[2,31-33] (Figure 8).

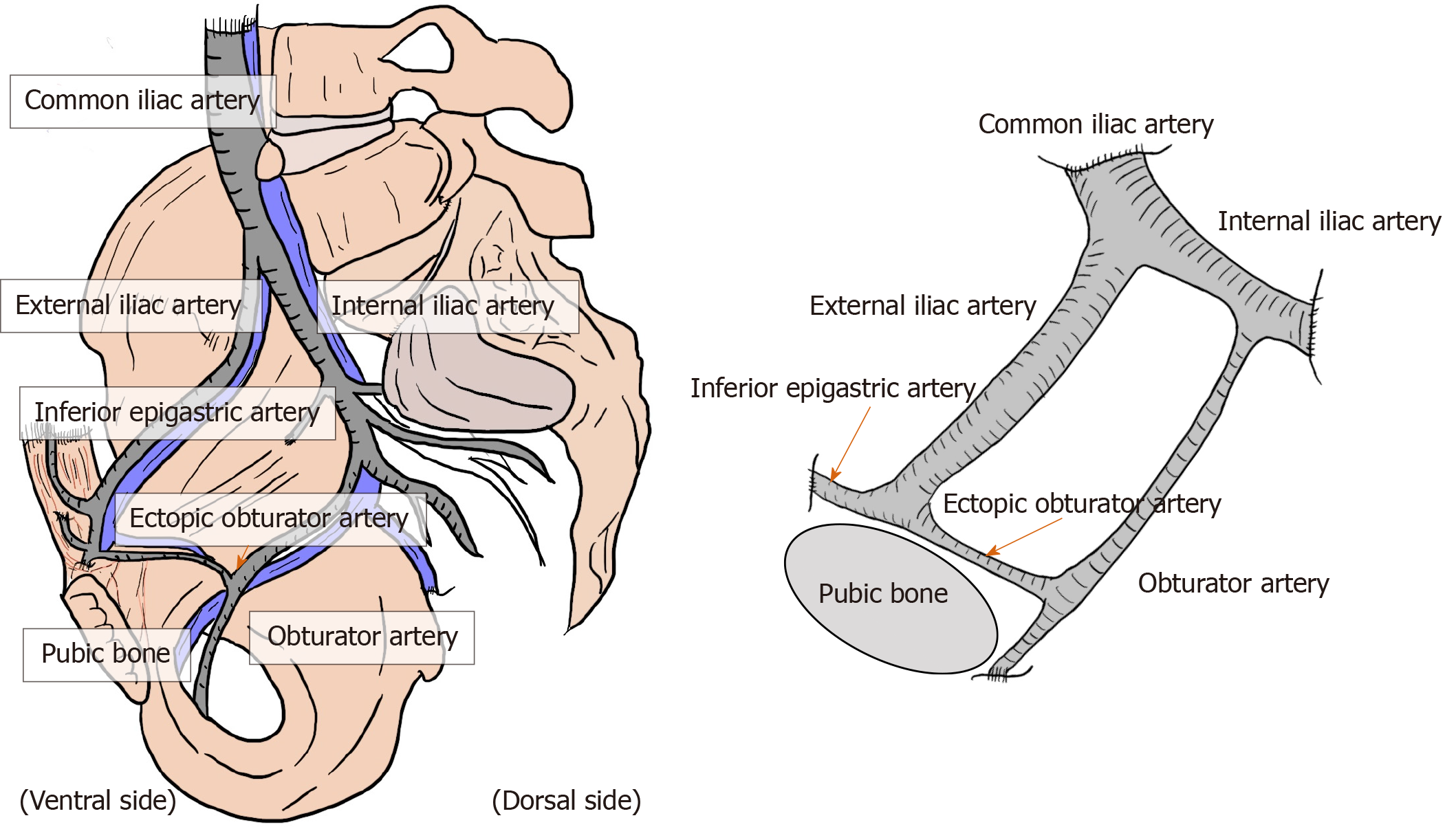

Brisk bleeding is difficult to control because of the dual vascular supply from the obturator and iliac vessels[2,31-33]. Dissection of the region around iliac vessels should be performed with special caution, carefully looking for the presence of a corona mortis, a vascular connection between the epigastric and obturator vessels[2,31-33]. Corona mortis is classically defined as an arterial anastomosis between the obturator artery and the inferior epigastric artery (IEA) via the ectopic obturator artery[2,31-33]. Due to the existence of the obturator artery, the IEA, common iliac artery, internal iliac artery, EIA, and obturator artery communicate annularly[2,31-33] (Figure 9). The incidence of this variant was documented at 20%–30%[33]. In addition, there may be several variants of anastomosing vascular branches between the pubic artery/vein and the epigastric and obturator vessels[2,31-33]. Collectively, this variable deep venous circle is called “the circulation of Bendavid” and is composed of the suprapubic, retropubic, deep inferior epigastric, and rectusial veins[2]. These small vascular tributaries may form a network that invests the pubic bone, Cooper’s ligament, and the direct and femoral spaces[2,31-33]. These vessels and the underlying pubic bone are covered by a very thin membrane (i.e., deeper visceral layer) that should not be disrupted[2,31-33].

Figure 9 Corona mortis.

Corona mortis and complicated vascular connection between the epigastric and obturator vessels. The corona mortis is classically defined as the arterial anastomosis between the obturator artery and the inferior epigastric artery via the ectopic obturator artery. The existence of the obturator artery results in annular communication between the inferior epigastric artery, common iliac artery, internal iliac artery, external iliac artery, and obturator artery. There may be several variants of anastomosing vascular branches. Brisk bleeding is difficult to control because of the dual vascular supply from the obturator and iliac vessels.

LAPAROSCOPIC TAPP REPAIR TECHNIQUE: KNACKS AND PITFALLS

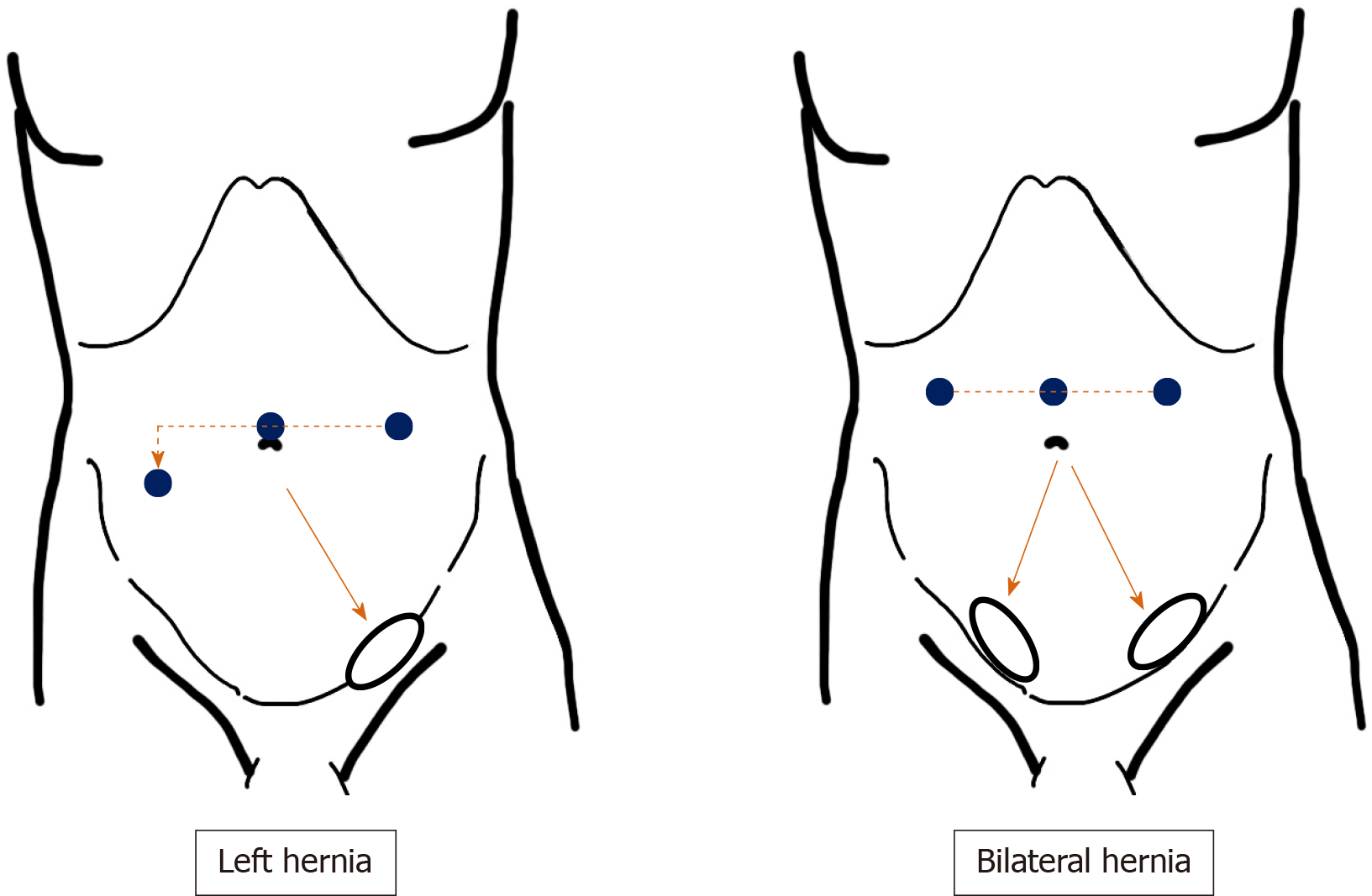

The patient is placed in the supine position. The Trendelenburg’s or lateral position is not required unless the bowel disrupts the surgical field. Initially, carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum at 8-12 mmHg is achieved through an umbilical port. Pneumoperitoneum stability is highly important for pneumo-preperitoneum. Carbon dioxide infiltration smoothly extends the PPS and adequately dissects each layer. Laparoscopic procedures are performed under various angled views. Although a flexible laparoscope is required, a strong light source is not. Hence, a 5-mm laparoscope (Endoeye Flex; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) is sufficient. Two working ports (3- and 5-mm ports) are placed, and two forceps are inserted at adequate angles to the target site. The port on the side opposite the target site is set lower than the umbilicus (Figure 10). The 5-mm port is used by the dominant arm of the main surgeon.

Figure 10 Port placement.

Placement of surgical ports recommended for transabdominal preperitoneal repair. Pneumoperitoneum is achieved through an umbilical port. Two working ports (3- and 5-mm ports) are placed, and forceps are inserted in each at adequate angles to the target site. The port at the side opposite the target site is set lower than the umbilicus. The 5-mm port is used by the dominant arm of the main surgeon.

To avoid unexpected injury, the bladder is collapsed by a urinary catheter, although a line demarcating the bladder is confirmed through the peritoneum. The IEA, femoral artery, and abdominal rectus muscle (ARM) are also identified through the peritoneum. The laparoscopic view with pneumoperitoneum makes an accurate diagnosis easy without any missed evaluations[2,33] because the plicae and fossae precisely indicate the hernial defect[2,33] (Figure 5). The laparoscopic view with pneumoperitoneum immediately identifies any overlooked hernias during the preoperative clinical examination.

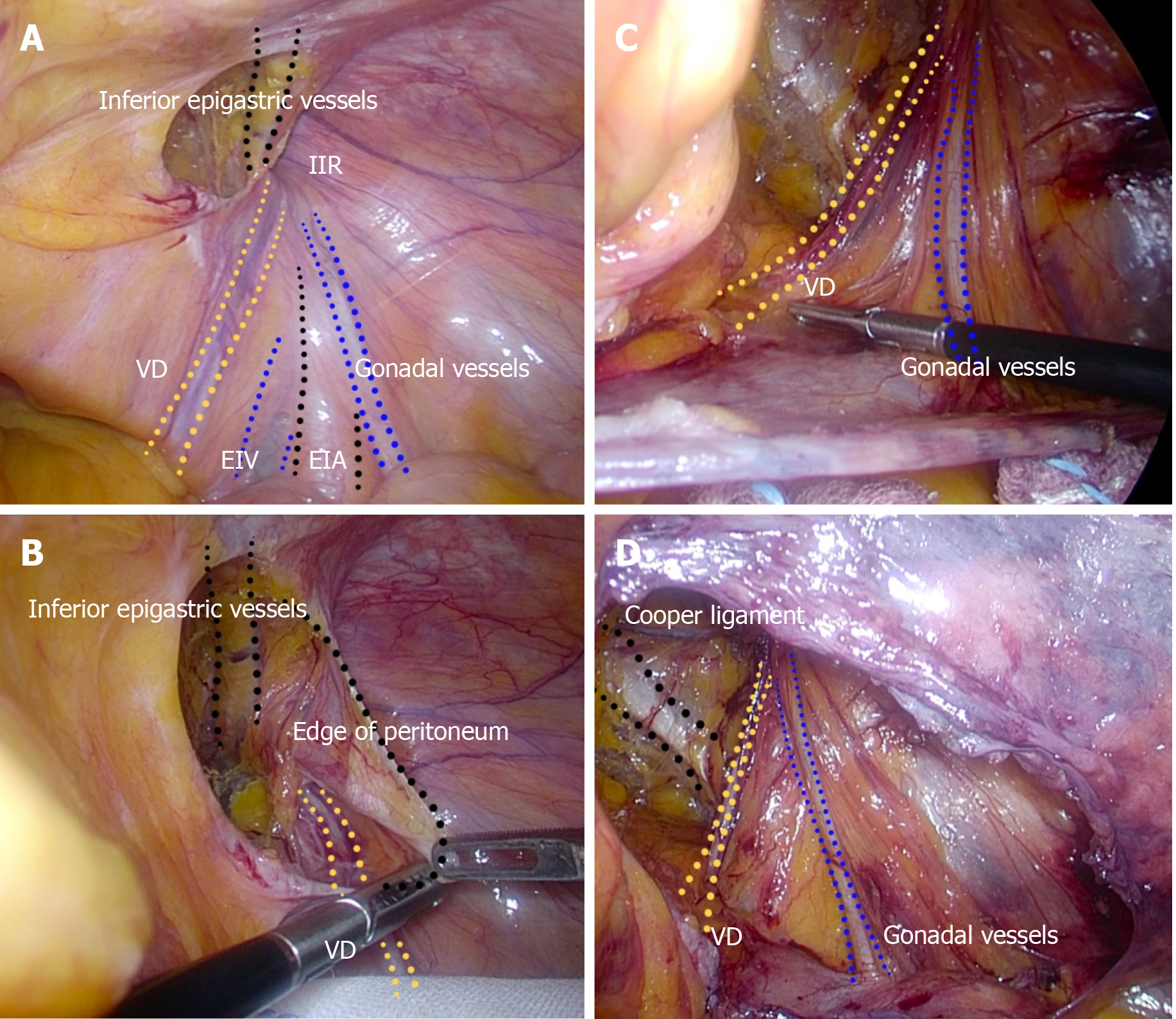

The peritoneum should be sharply cut without thermal damage because a pinched peritoneum caused by electric cautery or a coagulating scalpel makes closure of the peritoneum difficult after mesh placement. The VD and gonadal vessels should be completely preserved without any subtle damage. The VD crosses the IEA as the preperitoneal loop in the DVL. The VD and gonadal vessels are sharply dissected from the peritoneum without use of electric cautery or a coagulating scalpel from an adequate overhead view (Figure 11).

Figure 11 Complete preservation of the vas deferens and gonadal vessels.

A: Surgical procedure during dissection around the vas deferens (VD) and gonadal vessels. Familiarity with the important structures should be required. B and C: The VD and gonadal vessels should be completely preserved without any subtle damage. D: The VD and gonadal vessels are sharply dissected from the peritoneum without use of electric cautery or a coagulating scalpel, under an adequate overhead view. EIA: External iliac artery; EIV: External iliac vein; IIR: Indirect inguinal ring; VD: Vas deferens.

During exposure of Cooper’s ligament, all maneuvers should be performed gently and carefully. We should not forget the communicating vessels between the epigastric and obturator vessels (i.e., corona mortis) on Cooper’s ligament (Figures 7 and 9), and employ a blunt dissector (Endo Peanut; Medtronic plc, Dublin, Ireland) and/or soft surgical gauze for surgical procedures.

All topographic nerves should be preserved. Especially at the triangle of pain, tack fixation of the mesh is completed without involving nerves, thereby preventing neuropathy and chronic pain (Figure 8). Carelessness at the triangle of doom could cause brisk bleeding. Inconsiderate tacking to vessels could result in a dire situation during the surgery. The triangle of doom and triangle of pain configure a unique rhombus around the IEA (Figure 8), pulling important nerves and risky vessels aside as a curtain to safely fix the mesh.

We used three-dimensional polypropylene mesh (3DMax mesh, M size; BD Bard, Franklin Lakes, NJ, United States). The PPS is extended enough for mesh placement, and the dissected layer should be adequately switched between the SPL and DVL (Figure 3). To prevent mesh contact with the bladder, the dissection is performed between the SPL and DVL on the inner side, although the peritoneum is removed from the DVL on the outer side (Figure 4). Tack fixation in the direction of the bladder is never indicated. The demarcation line of the ARM and the conjunctive tendon of the AOM to the pubic bone are carefully confirmed (Figure 12), after which mesh placement is complete. Because tangential tacking is difficult, intentional compression of the abdominal wall is generally performed in a counter direction. The MO should be fully reinforced by mesh placed at the PPS (Figures 2 and 12). The obturator foramen can be covered during the TAPP repair.

Figure 12 Adequate area covered by mesh.

The relation between the myopectineal orifice (MO) and an area adequately covered by mesh. The MO should be fully reinforced by mesh placed at the preperitoneal space during transabdominal preperitoneal repair. ARM: Abdominal rectal muscle; DIH: Direct inguinal hernia; IIH: Indirect inguinal hernia; MO: Myopectineal orifice.

The peritoneum should be closed to prevent any contact of the mesh with visceral organs. Decreasing the pneumoperitoneum pressure allows adequate deflection of the peritoneum to accommodate the running suture. Stitches are tightly inserted on the inside, although the peritoneum on the outside can be roughly sutured. To avoid pneumatic swelling at the groin due to a temporal increase of intraperitoneal pressure when the patient awakes from general anesthesia, the peritoneal cavity should be completely deflated before abdominal closure.

COST-EFFECTIVENESS

Each country has its own health insurance system. The Japanese government employs a universal system. In Japan, surgery using laparoscopy or endoscopy for bilateral groin hernias is authorized by the governmental council, whereas robotic surgery is not allowed. Conventional repairs without general anesthesia have lower compensation, so only TAPP and TEP repairs offer hospital revenue in Japan. Although TAPP and TEP repairs are more expensive than conventional repairs[2,58], the cost-effectiveness of the TAPP repair has been documented in other countries[100,101].

Robotic surgery is also employed in the field of hernia surgery[102-104], and the articulated arms have a large advantage for approaches without visual disturbance by the MUP and bowel. Moreover, singleport robotic surgery (Single Port Robotic Surgical System, da Vinci Sp; Intuitive Surgical, Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, United States) is currently available. The direct cost and contribution margin are nearly equivalent between robotic and laparoscopic surgery[105], although robotic surgery had the higher cost for unilateral groin hernia[106].

DISCUSSION

The surgical procedure should be carefully chosen in each case based on the patient’s sex and age (pediatric, virile, senile). From the viewpoint of female fertility and male virility, anything causing female agenesis or male sterility should be avoided. Mesh material inherently causes postoperative atrophy in varying degrees[63,86-88,107]. Mesh contact with organs is associated with female agenesis, male sterility, neuropathy, and chronic pain[65,82-85,107]. Direct contact with mesh may cause obstruction of the VD and SC[107]. Only biological mesh can resolve these critical problems[68,69]. Although the TFR concept is important[6,40,108], thoughtless handling of synthetic mesh should be avoided in fecund young patients[82-85]. Potts’s repair (accompanied by Koop’s fixation in female patients) seems to be the first choice for this population of teenagers and children.

Based on the TFR concept and technical simplicity, hernioplasty with the mesh-plug and onlay patch has spread worldwide[109-111]. However, the mesh should reinforce the entire MO. Incomplete cover of the MO has resulted in recurrent hernias during long-term follow-ups after hernioplasty[17]. Direct inguinal and femoral hernias reappear as recurrent hernias, especially in female patients, who intrinsically have a wide pelvic space[17]. Surgical repairs at the PPS that fully covers not only the entire MO but also the obturator foramen should be chosen, especially for female patients[17], even though easy hernioplasty with a mesh plug and onlay patch works well in elderly men[106]. TAPP repair is advantageous as it covers both the MO and obturator foramen.

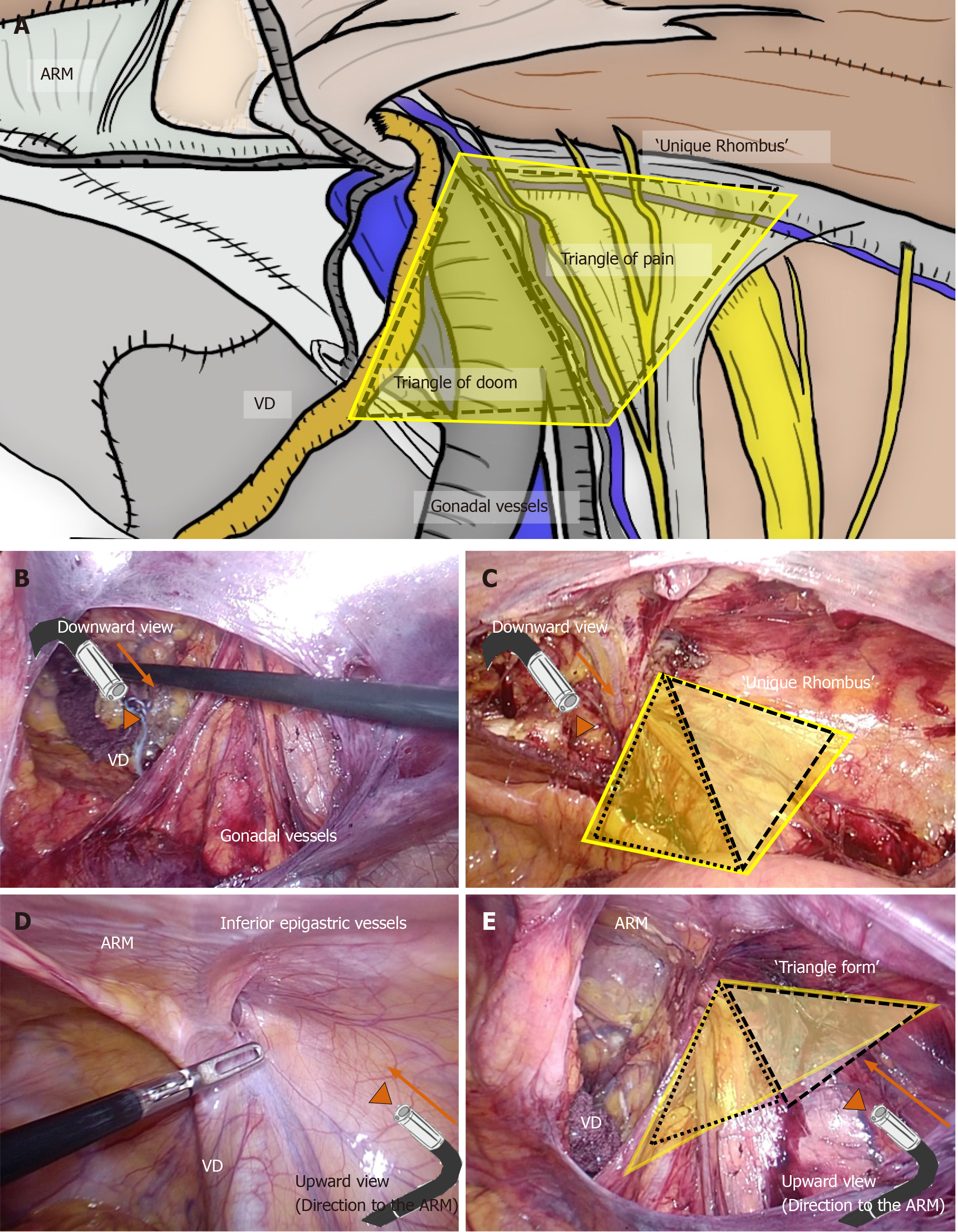

The triangle of doom and triangle of pain configure a unique rhombus around the IEA. Laparoscopists should ensure an adequate laparoscopic view during the TAPP repair. Although downward view requires safe preservation of the VD and gonadal vessels and sure exposure of Cooper’s ligament, downward view may easily mislead surgeons causing unexpected injuries of topographic nerves and vessels (e.g., GFN and femoral artery). Generally, a unique rhombus around the IEA seems to be a triangle on the upward view, and the ARM which is observed at the tangential wall is simultaneously observed at the roof (Figure 13). Thus, intraperitoneal anatomy including the ARM should be simultaneously recognized by upward view, for adequate mesh placement during TAPP. Optimal change of laparoscopic view during TAPP is very important.

Figure 13 Importance of upward view.

A: The triangle of doom and triangle of pain configure a unique rhombus around the inferior epigastric artery (IEA). Adequate change of laparoscopic view during transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) is very important. B and C: Although downward view requires safe preservation of the vas deferens and gonadal vessels and sure exposure of Cooper’s ligament, downward view may easily mislead surgeons causing unexpected injuries of topographic nerves and vessels. D and E: Generally, a unique rhombus around the IEA seems to be a triangle on the upward view, and the abdominal rectal muscle (ARM) is simultaneously observed at the roof. Thus, intraperitoneal anatomy including the ARM should be simultaneously recognized by upward view, for optimal mesh placement during TAPP. ARM: Abdominal rectal muscle; VD: Vas deferens.

TAPP repair may cause a bladder hernia at the suprapubic area[76] because surgical dissection produces a new weak area. To avoid an iatrogenic hernia related to a TAPP repair, complete mesh placement around the AOM should be confirmed by the demarcation line of the ARM and the conjunctive tendon of the AOM to the pubic bone, even though tangential tacking is difficult.

Interestingly, from the viewpoint of technical skills, pediatric herniorrhaphy reflects the individual ability of each surgeon or resident[112]. Sir William Heneage Ogilvie (1887-1971) postulated that, “I know more than a hundred surgeons whom I would cheerfully allow to remove my gallbladder but only one to whom I should like to expose my IC”[113]. Familiarity with inguinal anatomy is mandatory for successful hernioplasty[70]. In-depth anatomical knowledge of nerves and vessels at the PPS and MO is especially important. Astley Cooper (1768–1841) stated that, “No disease of (the) human body, belonging to the province of surgeons, requires in its treatment, a better combination of accurate anatomical knowledge with surgical skill than hernia in all its varieties”[7]. The combination of anatomical knowledge with surgical skill is important for successful outcomes[7]. High-quality repair is seriously required for groin hernia.

CONCLUSION

Both anatomical knowledge and skillful technique are essential for successful herniorrhaphy and hernioplasty for groin hernias. To date, laparoscopic TAPP repair with biological mesh seems to be a powerful technique for adult patients.