Published online Apr 27, 2020. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v12.i4.190

Peer-review started: December 20, 2019

First decision: January 6, 2020

Revised: March 12, 2020

Accepted: March 22, 2020

Article in press: March 22, 2020

Published online: April 27, 2020

Processing time: 125 Days and 0.1 Hours

Pelvic exenteration for locally advanced rectal cancer involving prostate has been performed via open surgery. Robotic pelvic exenteration offers benefits of better pelvic visualisation and dissection for bladder preserving prostatectomy with vesicourethral anastomosis, while achieving clear margins.

To determine the feasibility of robotic assisted bladder sparing pelvic exenteration.

We describe robotic assisted pelvic exenteration in three cases of locally advanced rectal cancer involving prostate and seminal vesicles (SV). The da Vinci S robotic system was used. Robotic console was docked at left oblique position for abdominal phase and redocked to between the patient’s legs for pelvic phase. All three cases were performed fully robotically at Tan Tock Seng Hospital by colorectal and urological teams.

Case 1: 67-year-old with low rectal tumour 3cm from anal verge involving the prostate. He underwent neo-adjuvant chemoradiotherapy and robotic abdominoperineal resection with en-bloc prostatectomy. Case 2: 66-year-old with low rectal tumour 3cm from anal verge involving prostate and bilateral SV. He underwent neo-adjuvant chemoradiotherapy and robot assisted ultra-low anterior resection with coloanal anastomosis and en-bloc prostatectomy. Case 3: 57-year-old with metachronous rectal tumour in the rectovesical pouch inseparable from the anterior mid rectum, prostate and bilateral SV. He underwent robot assisted ultra-low anterior resection with en-bloc prostatectomy. Bladder neck margin revealed cauterized tumour cells, and he underwent total cystectomy and ileal conduit creation. Histology revealed no residual tumour. All patients are currently disease free

Robot assisted bladder sparing pelvic exenteration can be safely performed in locally advanced rectal cancer with acceptable surgical outcome while preserving benefits of minimally invasive surgery.

Core tip: This paper adds on to the current evidence on feasibility of robotic surgery in pelvic exenteration for locally advanced rectal cancer. Studies on minimal invasive surgery for bladder sparing prostatectomy in rectal cancer scarce. Such extensive disease frequently requires total pelvic exenteration with ileal conduit formation. Our experience shows that minimal invasive surgery pelvic exenteration can be achieved using robotic surgery with good oncological outcome while at the same time, allows preservation of urinary and bowel function. This will encourage surgeons to consider the usage of robotic surgery in pelvic exenteration for rectal cancer.

- Citation: Heah NH, Wong KY. Feasibility of robotic assisted bladder sparing pelvic exenteration for locally advanced rectal cancer: A single institution case series. World J Gastrointest Surg 2020; 12(4): 190-196

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v12/i4/190.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v12.i4.190

Up to 10% of rectal cancers are locally advanced and many involve surrounding organs[1] necessitating extensive surgery for complete resection[2]. It is known that completeness of resection and clear resection margins (CRM) is a key factor in overall survival, disease free survival and is a predictor of local recurrence. In selected cases where rectal cancers are inseparable from other pelvic organs, en-bloc resection of urogenital organs are needed to achieve clear resection margin[3].

Traditionally, such complex operations have required open surgery. Even with the increasing adoption of minimally invasive surgery (MIS) for colorectal cancer, laparoscopic surgery in such large extirpative surgery is unquestionably challenging due to rigid laparoscopic instruments and narrow working space of the pelvis. It also involves a steep learning curve for surgeons, making it difficult to adopt this as a routine practice. With the adoption of robot in rectal cancer surgery in recent years, we see a role of robot in tackling difficult rectal cancer surgery. DaVinci© robotic system, with its 3-dimensional (3D) vision, enhanced ergonomics and elimination of tremor, has been shown to be non-inferior to laparoscopic surgery, in both short and medium-term outcomes. In locally advanced rectal cancer where the prostate is involved, robotic surgery enables preservation of the bladder after central exenteration by simplifying control of the dorsal venous complex (DVC) as well as performing an intracorporal anastomosis. The aim of our study is to describe three cases of advanced rectal cancer that used the DaVinci system to perform bladder sparing MIS pelvic exenteration and to demonstrate the feasibility of this procedure.

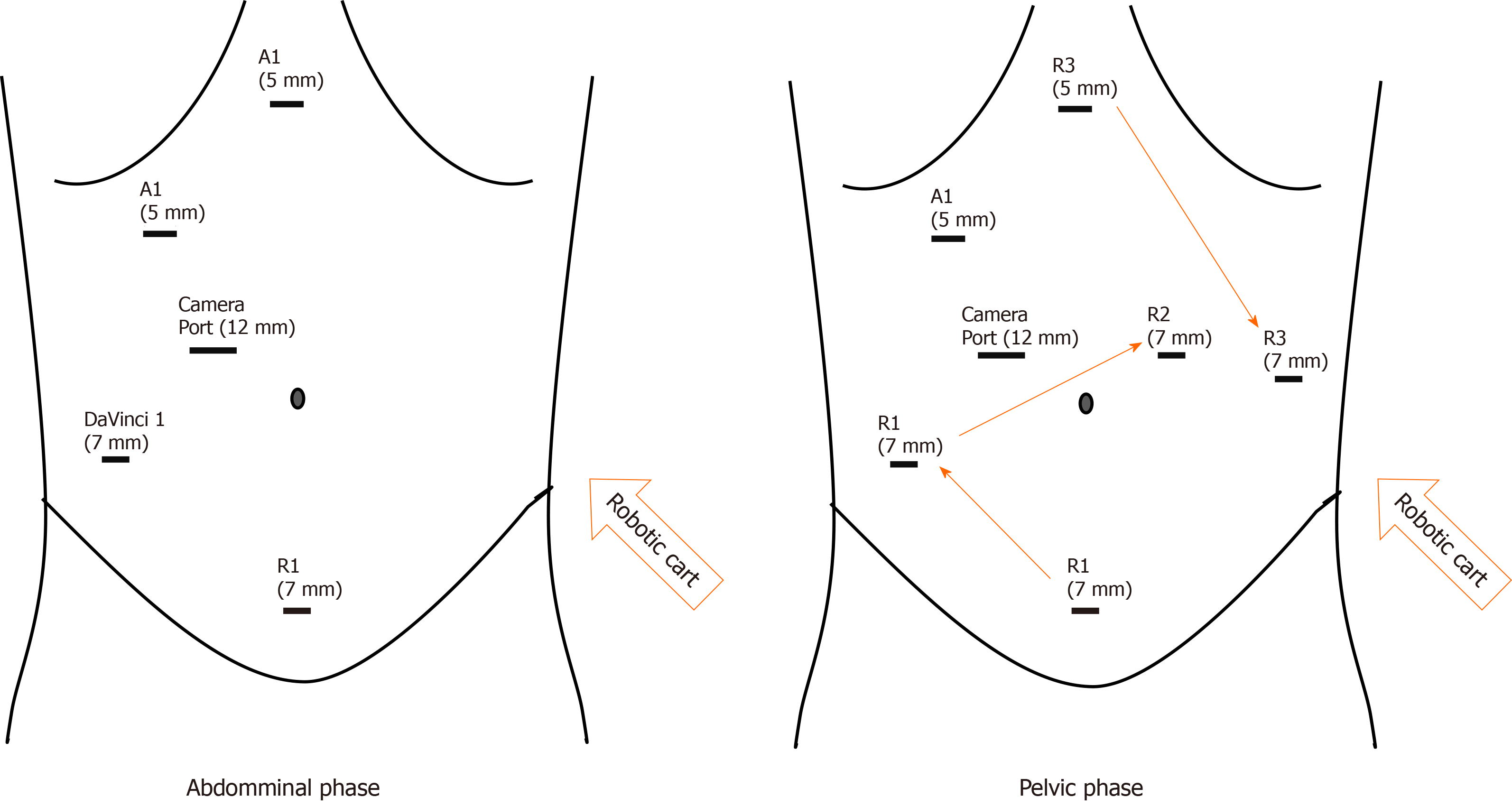

We present 3 cases of patients with locally advanced rectal cancers. All cases were treated in the same centre, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore, by a combination of colorectal and urological teams with the aid of the DaVinci S Robot system to perform fully robotic-assisted surgery. Patients were placed in modified Lloyd-Davis position after general anaesthesia. The surgery was divided into 2 phases; abdominal phase and pelvic phase. During the abdominal phase, the inferior mesenteric artery is ligated and left sided colon is mobilised. The splenic flexure is not routinely taken down unless there is concern of bowel length to anastomosis. The robot is docked from the patient left and ports placement as shown in Figure 1.

The pelvic phase requires the robot to be redocked in between the patient legs to facilitate total mesorectal excision (TME) and prostatectomy (We have since purchased the DaVinci Xi system after the publication of this paper and only single docking is required for the whole surgery). One assistant port is placed at right upper quadrant to assist in retraction and suction. After redocking, the pelvic phase begins with posterior dissection of the TME plane down till the pelvic floor. Lateral dissection was performed bilaterally as distal as possible, preserving lateral hypogastric nerve plexus. Anterior dissection and mobilisation of the rectum was not performed to avoid breaching the Denonvillier’s fascia thus causing tumour spillage.

Dissection began posteriorly with mobilisation of bilateral seminal vesicles (SV) and vas. The bladder was dropped anteriorly and the bladder neck transected in usual fashion before the lateral prostatic pedicles were divided bilaterally. After the DVC was divided and over sewn, the urethra was divided sharply and prostatectomy was completed after division of rectourethralis.

Following resection of prostate, distal rectal dissection is continued to pelvic floor until full TME is achieved. Distal transection is performed using laparoscopic stapler for intended ultralow anterior resection. Otherwise, perineal excision is performed for abdomino-perineal resection.

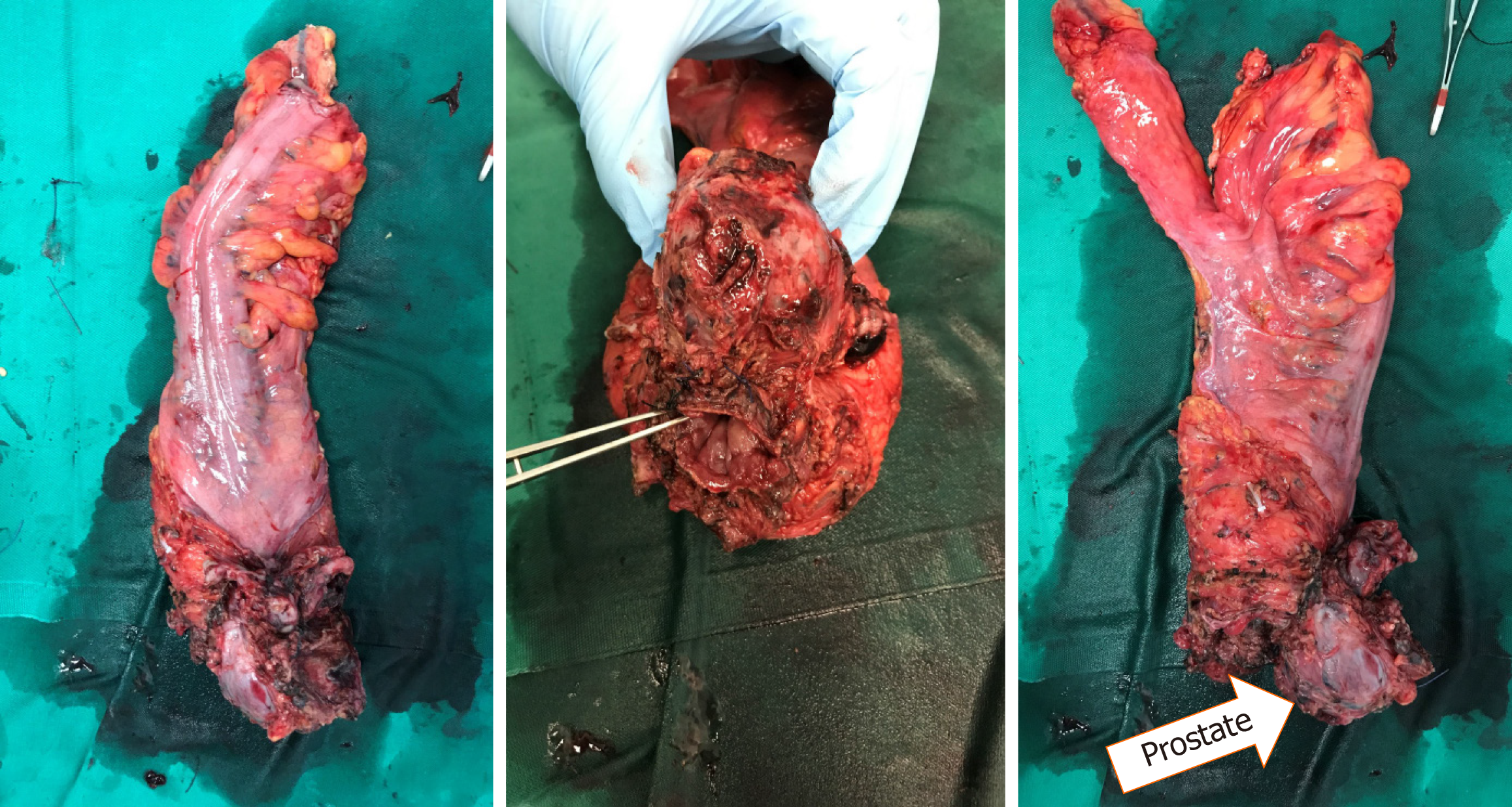

The rectal tumour is removed en-bloc with prostate either via a pfannenstiel incision or the perineal wound. Coloanal anastomosis is performed if restoration of bowel continuity is possible. After completion of coloanal anastomosis, the vesicourethral anastomosis was performed by the urology team in a continuous fashion and a fresh indwelling urinary catheter was inserted. A leak test was performed to ensure the anastomosis was watertight. A diverting ileostomy is created at the end of the surgery.

Statistical analysis was performed with Stata 13.0 (StatCorp LLC, Texas, United States) using paired t-tests for dependent quantitative dependent variables.

This study received ethics approval from the local ethics board.

The average distance from the AV was 4.6 cm. Our series had a mean estimated blood loss of 700 mL, and average length of stay was 12.6 d. Average time to flatus was 3.3 d and average time to stoma functioning was 4.6 d. Average Hb drop was 2.3 (95%CI: -4.31 to -0.28, P = 0.01) and no patients required any transfusion in the intra-operative or immediate peri-operative period (first 24 h) (Table 1).

| Patient | Age (yr) | Distance from AV (cm) | Pre-op Hb | Post-op Hb | Estimated blood loss (mL) | Margins | Underwent neo-adjuvant chemoradio-therapy |

| 1 | 67 | 3 | 13.4 | 12.6 | 800 | Negative | Yes |

| 2 | 57 | 8 | 14.6 | 11.2 | 600 | Cauterised edge | Yes |

| 3 | 68 | 3 | 13.3 | 10.6 | 700 | Negative | Yes |

| Average | 64 | 4.6 | 13.7 | 11.5 | 700 |

A 67-year-old man presented with per-rectal bleeding. He was diagnosed to have a low rectal tumour 3cm from the anal verge (AV) on colonoscopy. Staging computed tomography scans showed no evidence of metastatic disease. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) rectum done for local staging showed a clinical T4 tumour involving the prostate gland, with prominent peri-rectal lymph nodes. He underwent long course neo-adjuvant (NA) chemoradiotherapy and subsequently underwent a robot-assisted abdominoperineal resection with en-bloc prostatectomy with vesico-urethral anastomosis. His final histology was ypT3N1 disease, with clear margins. He was discharged well on post op day 4 and is currently disease free.

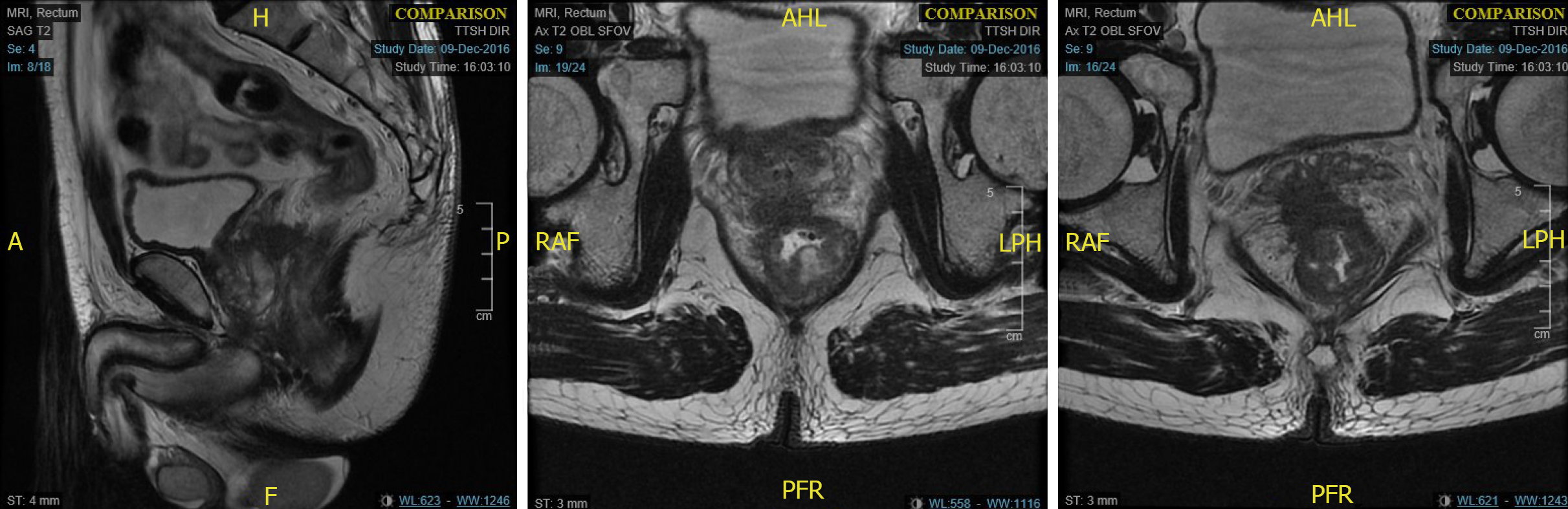

A 66-year-old man presented with change in bowel habits as well as tenesmus. He complained of reduced calibre of his stool with per-rectal bleeding mixed with his stools. He was found to have a low rectal tumour 3 cm from the AV on colonoscopy. Staging computed tomography scans did not show any distant metastases. MRI rectum showed a T4 low rectal tumour with invasion into the prostate and bilateral SV (Figure 2). Enlarged superior rectal nodes were seen on the MRI scan. He underwent long course NA chemoradiotherapy before undergoing a robot-assisted ultra-low anterior resection with J-pouch coloanal anastomosis and en-bloc prostatectomy with vesico-urethral anastomosis. Final histology showed ypT3N0 disease with clear margins (Figure 3). He completed adjuvant chemotherapy. His latest low anterior resection syndrome score is 18 (No low anterior resection syndrome) and his international prostate symptom score is 11.

A 57-year-old male with known previous pT4aN1b descending colon adenocarcinoma post left hemicolectomy, was diagnosed with recurrence in the rectovesical pouch on surveillance scans 3 year after his initial surgery. MRI rectum done for local staging showed an infiltrative soft tissue mass in the rectovesical pouch that was inseparable from the anterior mid rectum, prostate and bilateral SV. Radiological guided biopsy was performed and confirmed invasive adenocarcinoma with immunohistochemistry consistent with his previous biopsy. He underwent long course NA che-moradiotherapy before we performed a robot-assisted anterior resection with en-bloc prostatectomy and defunctioning ileostomy. Final histology confirmed the presence of recurrent colorectal adenocarcinoma. Cauterized tumour cells were seen at the bladder neck margin, while the rest of the margins were clear. His case was discussed at a multi-disciplinary team meeting and he underwent subsequent radical cystectomy and creation of ileal conduit. Subsequent histology from the radical cystectomy demonstrated no residual tumour.

Robot assisted exenteration was first reported in 2012[4] and subsequently the first case series was reported in 2014[5]. Another case series[6] published reported experience in multivisceral resection with robot assistance in, which the vagina and prostate were the most common organs resected. However, in these series, partial prostatic resection was performed without subsequent vesicourethral anastomosis or other forms of urinary diversion. Our study represents the first case series that reports on bladder sparing pelvic exenteration with vesicourethral anastomosis.

The DaVinci Robot system allows complex dissection and difficult anastomoses to be performed within the confines of the pelvis, with several advantages, including range of motion, reduction of tremor, binocular 3D vision, and magnification of field. These advantages are even more marked when operating within the tight confines of the male pelvis. This makes MIS more feasible with the aid of robot assistance and may result in less blood loss, lower transfusion requirements, decreased length of stay, with similar oncological outcomes.

Up to 10% of rectal cancers are locally advanced and pelvic exenteration is one of the few treatment modalities which offer potential survival gain and locoregional control[7]. However, the trade-off is that the peri-operative morbidity and mortality for such extensive surgery is high. In an era when laparoscopic surgery and robot assisted surgery are becoming common-place, the pelvic exenteration remains a procedure that is largely performed as open surgery. However, with the advancement of MIS in gynaecology and urology, acceptance for the suitability for MIS for pelvic exenteration is slowly gaining traction.

While laparoscopic exenteration in gynae-oncology[8] has been widely reported, there are only a few reports of laparoscopic exenteration in rectal surgery, and many of these have been reported to be extremely difficult, with a steep learning curve. The unique challenge of rectal surgery when compared to urological and gynaecological surgery in mainly due to the deeper pelvic dissection necessary, as well as the need for a low rectal anastomosis. This means that totally laparoscopic pelvic exenteration is extremely challenging due to technical difficulties[9], making this approach untenable for most, save for a few highly experienced laparoscopic surgeons. Our series has intra-operative blood loss ranging from 600-800mls, which is markedly less that what has been reported by other case series involving laparoscopic pelvic exenteration[10] and comparable to Shin et al[5].

Furthermore, the addition of bladder sparing en-bloc prostatectomy represents even more challenges, requiring an intra-corporeal vesico-urethral anastomosis. While there are several case reports for en-bloc bladder sparing pelvic exenterations, these were performed with open technique, with significant blood loss and prolonged post operatives stays[3]. The addition of a bladder sparing radical prostatectomy increases the risk of blood loss, especially during control of the DVC. Robot assisted surgery offers clear advantages to the surgeon, allowing quick ligation of the DVC intracorporeally. It also allows for complete prostatectomy to be performed, as opposed to partial prostatectomy as studies have shown that clear margins are associated with decreased rates of local recurrence, and it can be difficult to determine clear margins intra-operatively when performing a partial prostatectomy.

In our centre, robot assisted multivisceral resection is performed when adjacent organs are involved. Our case series reports only rectal cancers with prostate invasion because bladder sparing exenteration is rare. The bladder is usually routinely removed in open exenterations to do the difficulty of the vesicourethral anastomosis as well as questions regarding urinary control and function after bladder preservation. While mild incontinence is expected in up to 50% of patients in the immediate 12-18 mo following surgery, 5%-10% of patients may continue to have severe incontinence 12 mo after surgery regardless of the surgical approach. When extrapolated to include resection of the rectum, although we hope for similar urinary function most likely urinary function may be worse due to the close proximity of the hypogastric nerve during TME dissection. Use of the DaVinci robot system allows better 3D visualisation of the anatomy and precise dissection, reducing the risk of injury to the hypogastric nerve, and studies have shown that precise TME can be achieved using the robot with preservation of the pelvic autonomic nerves. This is reflected in our results, as patient 2 has been able to live on without the burden of a stoma. He has acceptable bowel and urinary function and has been able to maintain his premorbid quality of life.

In conclusion, our single centre early experience shows that robot assisted pelvic exenteration is feasible and safe in selected patient with locally advanced rectal cancers. The robotic approach can be applied to help patient’s immediate post op recovery, retaining the benefits of MIS, while allowing the surgeon to perform multi-visceral surgery in the pelvis. Although there are still challenges in multidisciplinary robotic surgery as well as limited expertise and a continued learning curve, this minimally invasive methodology of pelvic exenteration with significant functional advantages shows much promise. Further studies are needed to demonstrate its superiority over standard open exenteration.

Locally advanced rectal cancers can involve adjacent organs. In male, rectal cancers frequently involves seminal vesicles and prostate. Complete en-bloc removal of rectal cancer and adjacent organs with clear margin is key to successful oncological surgery, and this commonly requires a total pelvic exenteration with removal of urological and intestinal organ. Such extensive surgeries are usually performed via open technique. Majority of patients have a prolonged hospital stay due to wound pain and a decreased quality of life because of presence of permanent stomas.

Robotic surgery may have a role in introducing minimal invasive surgery to pelvic exenteration surgery for locally advanced rectal cancer. Robotic surgery allows anastomosis of bladder and urethra in the deep pelvis and can potentially reduce the rate of permanent stoma formation for patient in the future requiring total pelvic exenteration surgery.

To explore and demonstrate the benefits of robotic surgery as a form of minimal invasive surgery in total pelvic exenteration. To show the feasibility of minimally invasive surgery bladder preservation prostatectomy with total mesorectal excision. Patients are able to avoid a permanent ileal conduit and also maintain continuity of bowel when anal sphincter is spared.

Ethics approval was sought for this study. The data for 3 patients were included in the analysis and statistics including mean and paired t-tests for dependent variables with Stata 13.0 software. Parameters gathered included patient demographics, tumour characteristics such as distance from anal verge, peri-operative data including estimated blood loss and peri-operative haemoglobin, and margin status.

Our research showed that robot assisted bladder sparing pelvic exenteration is feasible. Although the safety and oncological outcomes for the procedure appears to be acceptable, more research and data is needed to confirm this early finding.

In conclusion, this pilot study of 3 patients using a novel technique of robot assisted bladder sparing pelvic exenterations is both feasible and safe. The advent of the DaVinci Robot allows complex pelvic surgery to be performed in a minimally invasive manner and the advantages of such an approach is clear, and performing such complex surgeries are pushing the boundaries of minimally invasive surgery. However, this is a small series and further data is needed to confirm the safety and oncological outcomes of this technique. Until then, patients need to be carefully selected before undergoing such a complex and challenging surgery from the minimally invasive approach.

Future research in this field will involve not just confirmation of the findings from this initial case series, but also the extent and limitations of the DaVinci Robot system. 3D vision and increased magnification in the pelvis are crucial to ensuring clear margin status as well as good functional outcomes for the patients. Complex reconstructive surgery such as bowel anastomoses and urethrovesical anastomoses highlight the advantages of the DaVinci Robot system but direct comparison between robot assisted laparoscopic cases and open cases may prove to be challenging due to the rare and unique nature of these patients and their locally advanced disease.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Singapore

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Xiao J, Zhang Z S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: A E-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Beyond TME Collaborative. Consensus statement on the multidisciplinary management of patients with recurrent and primary rectal cancer beyond total mesorectal excision planes. Br J Surg. 2013;100:E1-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sineshaw HM, Jemal A, Thomas CR, Mitin T. Changes in treatment patterns for patients with locally advanced rectal cancer in the United States over the past decade: An analysis from the National Cancer Data Base. Cancer. 2016;122:1996-2003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Smedh K, Khani MH, Kraaz W, Raab Y, Strand E. Abdominoperineal excision with partial anterior en bloc resection in multimodal management of low rectal cancer: a strategy to reduce local recurrence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:833-840. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nanayakkara PR, Ahmed SA, Oudit D, O'Dwyer ST, Selvasekar CR. Robotic assisted minimally invasive pelvic exenteration in advanced rectal cancer: review and case report. J Robot Surg. 2014;8:173-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Shin JW, Kim J, Kwak JM, Hara M, Cheon J, Kang SH, Kang SG, Stevenson AR, Coughlin G, Kim SH. First report: Robotic pelvic exenteration for locally advanced rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2014;16:O9-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hino H, Yamaguchi T, Kinugasa Y, Shiomi A, Kagawa H, Yamakawa Y, Numata M, Furutani A, Yamaoka Y, Manabe S, Suzuki T, Kato S. Robotic-assisted multivisceral resection for rectal cancer: short-term outcomes at a single center. Tech Coloproctol. 2017;21:879-886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Simillis C, Baird DL, Kontovounisios C, Pawa N, Brown G, Rasheed S, Tekkis PP. A Systematic Review to Assess Resection Margin Status After Abdominoperineal Excision and Pelvic Exenteration for Rectal Cancer. Ann Surg. 2017;265:291-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lawande A, Kenawadekar R, Desai R, Malireddy C, Nallapothula K, Puntambekar SP. Robotic total pelvic exenteration. J Robot Surg. 2014;8:93–96. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Trastulli S, Farinella E, Cirocchi R, Cavaliere D, Avenia N, Sciannameo F, Gullà N, Noya G, Boselli C. Robotic resection compared with laparoscopic rectal resection for cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of short-term outcome. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:e134-e156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Patel H, Joseph JV, Amodeo A, Kothari K. Laparoscopic salvage total pelvic exenteration: Is it possible post-chemo-radiotherapy? J Minim Access Surg. 2009;5:111-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |