Published online Apr 27, 2020. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v12.i4.178

Peer-review started: December 31, 2019

First decision: February 19, 2020

Revised: March 18, 2020

Accepted: March 30, 2020

Article in press: March 30, 2020

Published online: April 27, 2020

Processing time: 114 Days and 1.6 Hours

Pelvic recurrence after rectal cancer surgery is still a significant problem despite the introduction of total mesorectal excision and chemoradiation treatment (CRT), and one of the most common areas of recurrence is in the lateral pelvic lymph nodes. Hence, there is a possible role for lateral pelvic lymph node dissection (LPND) in rectal cancer.

To evaluate the short-term outcomes of patients who underwent minimally invasive LPND during rectal cancer surgery. Secondary outcomes were to evaluate for any predictive factors to determine lymph node metastases based on pre-operative scans.

From October 2016 to November 2019, 22 patients with stage II or III rectal cancer underwent minimally invasive rectal cancer surgery and LPND. These patients were all discussed at a multidisciplinary tumor board meeting and most of them received neoadjuvant chemoradiation prior to surgery. All patients had radiologically positive lateral pelvic lymph nodes on the initial staging scans, defined as lymph nodes larger than 7 mm in long axis measurement, or abnormal radiological morphology. LPND was only performed on the involved side.

Majority of the patients were male (18/22, 81.8%), with a median age of 65 years (44-81). Eighteen patients completed neoadjuvant CRT pre-operatively. 18 patients (81.8%) had unilateral LPND, with the others receiving bilateral surgery. The median number of lateral pelvic lymph nodes harvested was 10 (3-22) per pelvic side wall. 8 patients (36.4%) had positive metastases identified in the lymph nodes harvested. The median pre-CRT size of these positive lymph nodes was 10mm. Median length of stay was 7.5 d (3-76), and only 2 patients failed initial removal of their urinary catheter. Complication rates were low, with only 1 lymphocele and 1 anastomotic leak. There was only 1 mortality (4.5%). There have been no recurrences so far.

Chemoradiation is inadequate in completely eradicating lateral wall metastasis and there are still technical limitations in accurately diagnosing metastases in these areas. A pre-CRT lymph node size of ≥ 10 mm is suggestive of metastases. LPND may be performed safely with minimally invasive surgery.

Core tip: Lateral pelvic recurrence after rectal cancer surgery is still a major problem. There have been differences in the treatment of suspicious lateral pelvic lymph nodes between the East and West, treating this as either regional or systemic disease. Lateral pelvic lymph node dissection is a topic of debate in the treatment of these patients. In this study, we evaluate our single-center data, showing our short-term outcomes. Minimally invasive surgery, especially with the robotic platform is shown to be safe and feasible in lateral pelvic lymph node dissection.

- Citation: Wong KY, Tan AM. Short term outcomes of minimally invasive selective lateral pelvic lymph node dissection for low rectal cancer. World J Gastrointest Surg 2020; 12(4): 178-189

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v12/i4/178.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v12.i4.178

Total mesorectal excision (TME) has been established as the gold standard for treatment of low rectal cancer. This technique, however, only removes the mesorectal lymph nodes. The incidence of lateral pelvic lymph nodes (LPLN) metastasis in locally advanced low rectal cancer has been shown to be as high as 18%. Pelvic recurrence after rectal cancer surgery is a major concern, and one of the most common types of recurrence after TME is from lateral pelvic lymph node metastasis[1,2].

In Western countries, lateral pelvic lymph node metastases have always been considered as systemic disease and treated as metastatic disease. Japanese surgeons, however, have a different approach and considered lateral pelvic disease as regional disease, with LPND being potentially curative. Some studies have reported improved local control and possibly survival benefits in patients undergoing LPND for metastatic LPLN after neoadjuvant CRT[3].

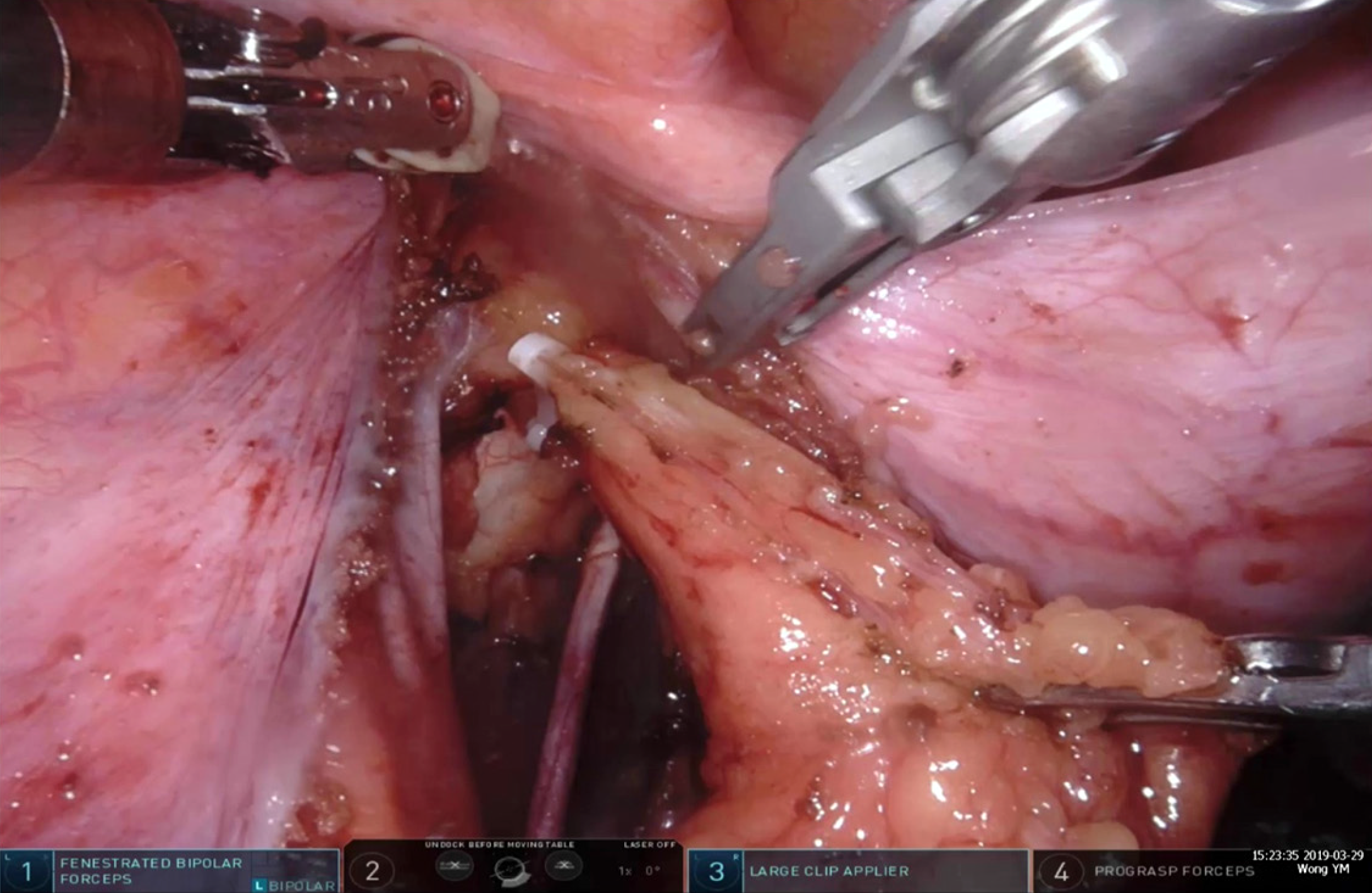

LPND is not routinely performed outside of Japan because of its associated morbidity. The procedure has been associated with urinary and sexual dysfunction, longer operative time and larger volume of blood loss. LPND has traditionally been performed via open surgery but recent small studies have reported the feasibility of laparoscopic surgery. Laparoscopic LPND is a technically challenging procedure and robotic surgery may have an advantage owing to the flexibility of the instrument, 3D stereoscopic visuals and its ability to work in a confined lateral pelvic space.

This study aims to share our experience in minimally invasive LPND in rectal cancer and reaffirm its safety and feasibility.

This study was approved by the local ethics review board. Data was collected prospectively in a tertiary referral hospital, Tan Tock Seng Hospital from October 2016 to November 2019 and retrospectively reviewed.

A total of 22 patients were diagnosed with locally advanced low rectal cancer (T3+/N+) and underwent curative surgery during this period of time. Patients with radiologically positive LPLN were included in the study. Radiologically positive pelvic lymph node metastases were defined as lymph nodes larger than 7 mm in short axis measurement or had abnormal morphology on imaging studies. Patients with rectal neuroendocrine tumors were also included if they had suspicious LPLN as well. All patients underwent minimally invasive surgical approaches.

All cases were discussed in multidisciplinary tumor board meeting. Majority of the patients underwent long course neoadjuvant CRT according to multidisciplinary tumor board meeting recommendations. These patients received between 40-50 Gy in 25# for 5 wk with twice daily capecitabine. Repeat magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was routinely performed 5 to 6 wk after completion of CRT for evaluation of tumor response and surgical planning. TME and LPND were performed regardless of the response and size of the LPLN after CRT (Figure 1 and Figure 2). All patients included in the study underwent TME and LPND, except 1 patient who had only the LPND performed for an isolated lateral pelvic lymph node recurrence a year after TME surgery. All cases were performed either laparoscopically or robotically. The decision for performing the surgery via laparoscopy or robotic surgery was based on availability and affordability of the robotic system. All patients who underwent CRT and low anterior resection had a diverting ileostomy performed together at the same time. End colostomy was formed for patients who had abdominoperineal resection or Hartmann’s procedure respectively.

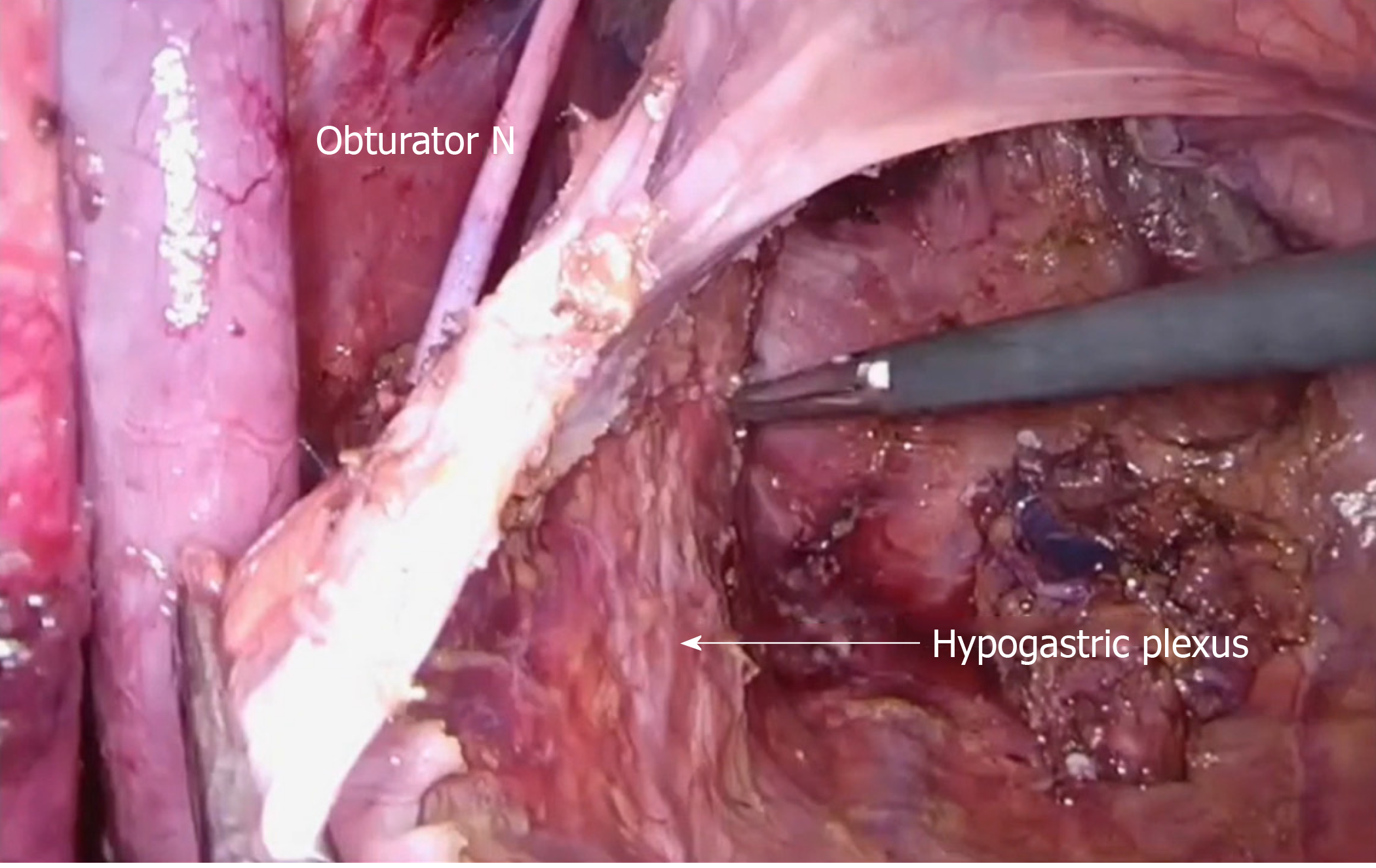

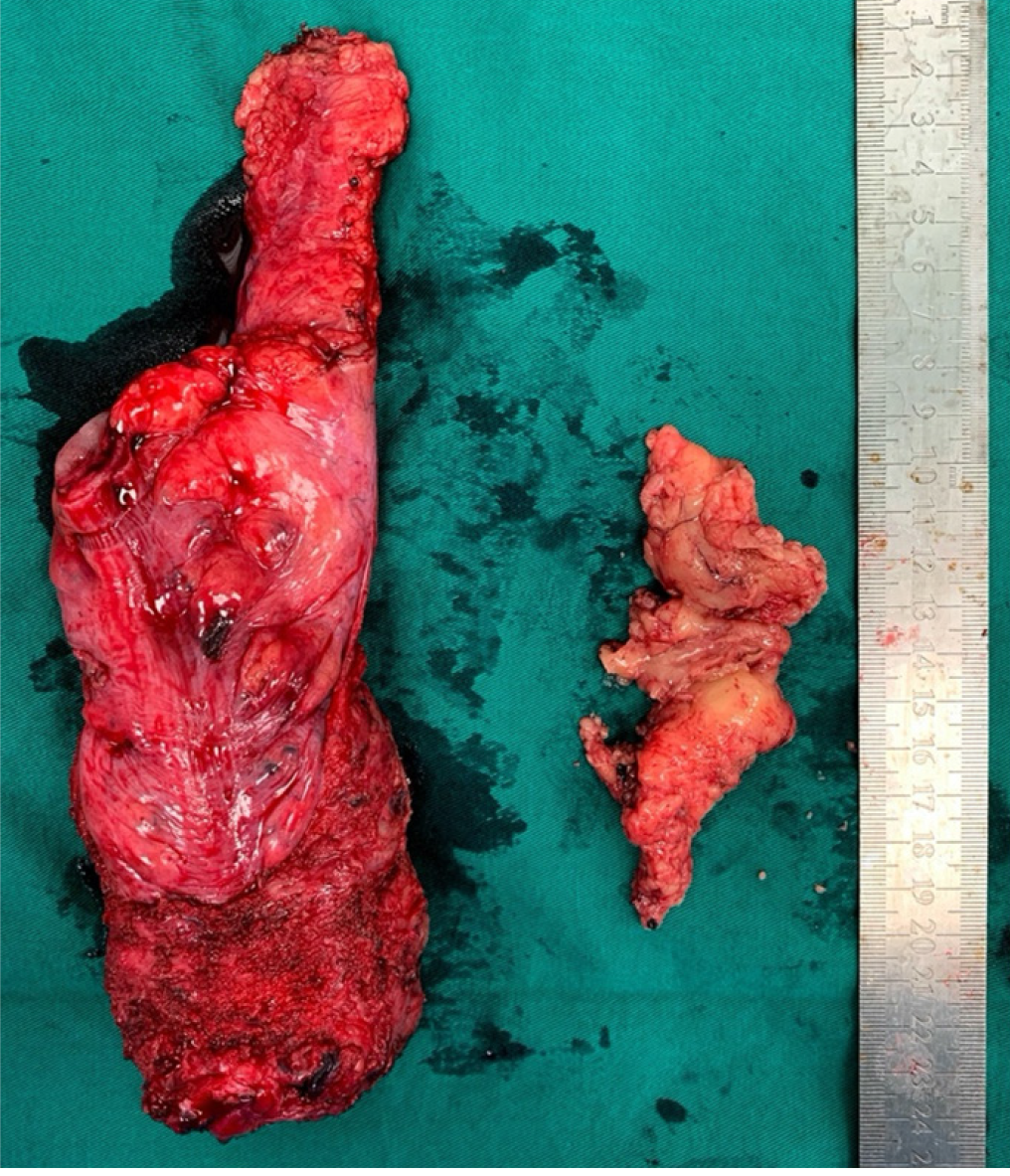

The dissection of LPLN was performed after completion of TME and transection of the distal rectum. LPND for rectal cancer in our institution places emphasis on complete clearance of internal iliac and obturator compartments, as lymph nodes at these two compartments have the highest incidence of metastasis in low rectal cancer[4]. External iliac and common iliac lymph nodes were cleared only if pre-operative imaging showed disease involvement. This is to minimize the side effects of LPND, such as chronic lymphedema of the lower limb and injury to the genitofemoral nerve. In laparoscopic cases, dissection of the lateral sidewall was carried out using monopolar diathermy and an ultrasonic energy device. For robotic cases, a total robotic technique was used, including mobilization of colon, ligation of inferior mesenteric artery (IMA), TME and LPND. The Da Vinci S or Xi system was utilized for these robotic cases. LPND was only performed on the side of suspected metastatic LPLN seen on the pre-CRT MRI scan. Branches of the internal iliac artery were ligated if necessary, to allow access to the deep pelvic side wall or when metastatic lymph nodes were adhered to the vessel. The superior vesicle artery on either side was spared if bilateral LPND was performed. This was to preserve arterial perfusion to the bladder. The obturator nerve was not routinely sacrificed if there was no definite involvement by metastatic lymph nodes (Figure 3 and Figure 4). The ureterohypogastric fascia was preserved in all cases to preserve genitourinary function, and only sacrificed if there was tumor involvement (Figure 5). Lymphofatty tissues were excised en bloc as a whole and we do not practice cherry-picking of metastatic lymph nodes (Figure 6 and Figure 7).

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 24.0. Categorical data were expressed with numbers with percentages, and continuous data were expressed as medians with a range.

The median age of patients was 65 (44-81). Majority of these patients were male (18/22, 81.8%). The median distance of the tumor from the anal verge was 5 cm (2-7). Average body mass index of the patients included was 23.4 (14.2-34.3). 18 of the patients completed neoadjuvant CRT before surgery. Of the patients with adenocarcinoma, one patient already had previous pelvic radiation, and another patient was not suitable for pre-operative CRT in view of his poor performance status and lack of social support. There were two patients with neuroendocrine tumors and hence were not given neoadjuvant CRT (Table 1).

| Sex (n) | |

| Male | 18 |

| Female | 4 |

| Age (yr, mean, range) | 65 (44–81) |

| ASA grade (%) | |

| 1 | 1 (4.5) |

| 2 | 19 (86.4) |

| 3 | 2 (9.1) |

| Histology (%) | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 20 (90.9) |

| Neuroendocrine | 2 (9.1) |

| Distance from anal verge (cm) | 5 (2–7) |

| BMI (kg/m2, mean, range) | 23.4 (14.2–34.3) |

| Pre-op chemoradiation (%) | 18(81.8) |

| Final TNM stage (%) | |

| I | 1 (4.5) |

| II | 4 (18.2) |

| III | 14 (63.6) |

| IV | 1 (4.5) |

| Pathological complete response | 1 (4.5) |

| Isolated LN recurrence | 1 (4.5) |

| No. of lymph nodes harvested per side (median, range) | 10 (3-22) |

| Patients with positive LPLN metastases on final histology (%) | 8 (36.4) |

| Median size pretreatment LPLN (mm) | 10 |

The 81.8% of patients had unilateral LPND whereas the remaining patients had bilateral LPND. The types of surgery performed included low anterior resection (72.7%, n = 16), inter-sphincteric resection (9.1%, n = 2), abdominoperineal resection (9.1%, n = 2), Hartmann’s procedure (4.5%, n = 1) and only pelvic lymph node dissection (4.5%, n = 1). Mean operative time for LPND was 70 min (35-120) and median total blood loss (including TME) was 100 mL (50-500). Nineteen patients (86.4%) had the procedure performed robotically. There was only 1 conversion (4.5%) to open surgery due to involvement of main trunk of internal iliac vein by metastatic lateral lymph (Table 2).

| Access (%) | |

| Robotic | 19 (86.4) |

| Laparoscopic | 3 (13.6) |

| Type of surgery (%) | |

| Low anterior resection | 16 (72.7) |

| Low anterior resection with intersphincteric resection | 2 (9.1) |

| APR | 2 (9.1) |

| Hartmann’s procedure | 1 (4.5) |

| Isolated LPND | 1 (4.5) |

| Laterality of LPND (%) | |

| Unilateral | 18 (81.8) |

| Bilateral | 4 (18.2) |

| Operative time for LPND (min, median, range) | 70 (35-120) |

| Total blood loss (mL, median, range) | 100 (50-500) |

| Conversion to open surgery (%) | 1 (4.5) |

Most patients had a final pathological stage III tumor (63.6%, n = 14). Only one patient had a complete pathological response. The median number of LPLN harvested was 10 (3-22) per pelvic side wall. Eight patients (36.4%) had positive metastases identified in the lymph nodes harvested. The median pre-CRT size of these positive lymph nodes was 10 mm (Table 3).

| Length of stay (d, median, range) | 7.5 (3-76) |

| Day to removal of urinary catheter (median, range) | 3 (1-37) |

| Complications (%) | |

| Lymphocele requiring drainage | 1 (4.5) |

| Anastomotic leak | 1 (4.5) |

| Follow up duration (mo, median, range) | 18(1-36) |

| Local recurrence during follow up | 0 |

On further analysis of patients with positive lymph nodes, 6 out of 8 patients (75%) had a pre-CRT lymph node size of ≥ 10 mm. There were 10 patients with a pre-CRT lymph node size of ≥ 10 mm, and 60% of them eventually had LPLN metastases on final histology.

The median length of stay was 7.5 d (3-76), with a median follow up of 18 mo (1-36). The median number of days which a urinary catheter was kept was 3 d (1-37). Only 2 patients had re-insertion of their urinary catheter after failure to void, but these were still eventually removed at 20 and 37 d respectively (Table 4).

| No. | Pre-op CRT | Pre-CRT Size(mm) | Post-CRT Size(mm) | LN positivity | Remarks |

| 1 | Yes | 6 | 6 | No | |

| 2 | Yes | 8 | 5 | No | |

| 3 | No | 7 | NA | No | Previous radiation for prostate cancer |

| 4 | Yes | 8 | 0 | No | Enlarged LPLN resolved after CRT |

| 5 | Yes | 7/7 (L/R) | 4/6 (L/R) | No | |

| 6 | Yes | 11 | 10 | No | |

| 7 | Yes | 8 | 5 | No | |

| 8 | No | 15 | NA | Yes | Neuroendocrine tumor |

| 9 | Yes | 10 | 8 | No | |

| 10 | Yes | 11/8 (L/R) | 7/8 (L/R) | Yes | Only the left side was positive for metastases |

| 11 | Yes | 10 | 8 | Yes | |

| 12 | No | 6 | NA | No | Not suitable for CRT in view of performance status and poor social support |

| 13 | Yes | 5 | 5 | Yes | |

| 14 | Yes | 9 | 7 | No | |

| 15 | Yes | 10 | NA | Yes | Isolated LPLN recurrence after TME surgery 1 yr ago |

| 16 | No | 10 | NA | Yes | Neuroendocrine tumor |

| 17 | Yes | 11 | 11 | No | |

| 18 | Yes | 11 | 5 | No | |

| 19 | Yes | 14 | 10 | Yes | |

| 20 | Yes | 6 | 6 | No | |

| 21 | Yes | 7 | 7 | No | |

| 22 | Yes | 7 | 6 | Yes |

Morbidity was generally low in this analysis, with only 1 lymphocele (4.5%) requiring radiological guided drainage, and 1 anastomotic leak (4.5%). There was only one mortality (4.5%), which was the patient who developed the anastomotic leak requiring repeat surgical intervention, and eventually demised from pneumonia after a prolonged hospital stay. None of the patients have developed any local recurrence during their follow up within the time frame of this study.

TME is the gold standard treatment for rectal cancer and has successfully reduced local recurrence and improved survival since its introduction in 1990s. However, local recurrence in the lateral compartment can still occur after TME because of the lateral lymphatic drainage of low rectum. It is reported that lateral pelvic nodal metastasis ranges from 14% to 22% and the incidence of LPLN metastasis increases with a lower location of rectal cancer[5-7].

The use of multimodal treatments has reduced the rate of local recurrence but cannot completely eliminate lateral pelvic disease. In a series of 366 patients who underwent chemoradiotherapy and TME for T3/N+ locally advanced rectal cancer, lateral recurrence occurred in 8% of the patients[2]. Most of these were isolated lateral lymph node recurrences and almost half of them did not have distant metastasis. These studies show the inadequacies of CRT in eliminating lateral pelvic metastasis and raise the question on whether extended lymphadenectomy of the lateral compartment during the index surgery could have prevented recurrence in these patients. Similarly, Kusters et al[8] also reported a lateral local recurrence rate of 33.3% in patients who had lateral nodes larger than 1cm despite receiving radiotherapy.

Local recurrence is associated with significant morbidity from local compression effects and pain, and salvage surgery is not always possible. Data from the Dutch TME trial showed that lateral recurrences made up 25% of all pattern of recurrences and survival is poor especially for patients who previously received radiotherapy[9].

There is still no consensus on the treatment of clinically overt lateral lymph node metastasis. LPND in rectal cancer is not performed routinely because it is widely held that lateral nodal metastasis is a systemic disease. However, a nationwide multicenter study in Japan evaluating LPND showed that the survival of patients with LPLN confined to the internal iliac region had a survival comparable to that of patients with a mesorectal N2a disease[10]. If the LPLN metastases extended past the internal iliac region, the survival was comparable to that of N2b disease, but still better than stage IV disease. The results suggested that LPLN metastasis, especially those from the internal iliac region should be considered as regional disease.

Most western surgeons have refrained from performing LPND because of the lack of evidence on survival benefit and also the perceived side effects of prolonged operative time, increased blood loss and genitourinary dysfunction[11]. Japanese surgeons on the other hand, have been advocating either prophylactic or therapeutic LPND in low rectal cancer without CRT. LPND has been the standard surgical procedure for locally advanced low rectal cancer, and it has been suggested that this may reduce local recurrence and improve survival outcome[12,13].

In the recently published multicenter randomized controlled non-inferiority JCOG0212 trial, it compared patients who had TME against patients who had TME plus LPND without any overt lateral pelvic node metastasis, defined by authors as LPLN less than 1 cm in size[1]. There was a slightly longer operative time and blood loss in the TME plus LPND group. However, there was no significant difference in terms of post-operative complications, anastomotic leak or urinary dysfunction. It showed that LPND can be performed safely with no significant morbidities if performed in high volume centers. The Japanese Society of Cancer of Colon and Rectum strongly recommends LPND in patients with clinically suspicious lateral nodes, with a weaker recommendation for prophylactic LPND[1]. Prophylactic LPND however, does carry a risk of overtreatment. The JCOG 0212 trial showed a 7% rate of lateral pelvic local recurrence for the TME-only group, of which a significant portion of these could possibly have been treated with pre-op CRT. Thus, the important question is how to identify LPLN that are involved with residual disease after CRT and selecting them for LPND.

Accurate diagnosis of lateral lymph node metastasis based on imaging is challenging, and the size of the lymph node has been shown to be the most useful compared to other diagnostic criteria. Various size criteria have been proposed with variable sensitivities and specificities, ranging from 5 mm to 10 mm. Ogura et al[14] reported a high local recurrence rate when suspected LPLN exceeded 7 mm on short axis diameter. The authors reported a 5-year local recurrence rate of 5.7% for patients who underwent CRT, TME and LPND compared to 19.5% in patients with CRT and TME only. Akasu et al[15] evaluated the accuracy of MRI in pre-operative staging and found it to be highly predictive of lateral pelvic node involvement. They found that size criteria was the most accurate in diagnosing metastatic lymph node, and this concurs with our findings too that a large LPLN is associated with a higher rate of positive lymph node metastases.

Recently, selective LPND is gaining recognition and has been adopted by certain centers in the East to completely eliminate of the possibility of residual metastasis in the lateral node after CRT, in contrast to prophylactic LPND which has been traditionally practiced. Akiyoshi et al[3] reported a retrospective study of 127 patients, of which 38 patients underwent selective LPND after CRT if there were suspicious LPLN > 7 mm on the initial staging scan. 66% of LPLN that were suspicious on pre-operative imaging had persistent disease on histology after LPND despite undergoing CRT. They did not find any difference in survival between patients who underwent TME only compared to those who underwent TME with LPND. The latter group is theoretically supposed to have more advanced disease due to the presence of lateral pelvic metastasis. Upon further subgroup analysis of patients who underwent TME and LPND, patients with pathological proven LPLN metastasis had a similar survival and local recurrence rate compared to patients with negative lateral LN metastasis. This suggests that LPND after CRT may confer a survival benefit in patients with LPLN metastasis.

Similarly, another study from Korea suggested clearance of all enlarged lateral nodes seen on initial imaging, regardless of its response to CRT[16]. The authors found that enlarged LPLN which showed good response to CRT (< 5 mm) may still develop local lateral recurrence in up to 22% of cases. All patients with enlarged pre-CRT lymph nodes were subjected to TME and LPND and subsequently, no lateral recurrence was reported in their follow up.

Our results show that a pre-CRT LPLN size of > 10 mm is highly predictive of metastatic disease. Even if some of these lymph nodes responded to CRT and shrank in size, final histology after LPND still showed persistent malignancy in these nodes. If these were left alone without surgery, a lateral recurrence is almost inevitable, and subsequent LPND in a previously irradiated field and presence of the neorectum in the pelvis will surely be technically challenging.

LPND is usually performed as part of the surgery after completion of TME. But even as minimal invasive surgery becomes routine in rectal cancer surgery, it is necessary to evaluate whether LPND is safe and effective via these approaches. We had one case of lymphocele requiring percutaneous drainage in the third patient of our series, early on in our experience with MIS LPND. We have mitigated the risk of lymphatic leakage by securing large lymphatic channel with clips and leaving surgical drain in the post dissection lateral pelvic space. By doing do, we have not encountered further clinically evident lymphocele in our subsequent cases (Figure 8).

Neuroendocrine tumors were also included as the objective of the study was to demonstrate the safety and feasibility of minimally invasive approaches for LPND. Robotic and laparoscopic approaches are the standard techniques in our institution for the treatment of rectal cancer. Most of the LPND in our study were performed robotically. The robotic platform provides an advantage over conventional laparoscopic surgery because of the flexibility of its endo-wrist in a tight lateral pelvic space. 3D visualization and a stable operating platform allows precise dissection with preservation of neurovascular structures. There was one conversion to open surgery from laparoscopic surgery due to direct invasion of a metastatic lateral lymph node into the main trunk of the internal iliac vein, requiring conversion in order to gain vascular control before dissection.

The main limitation of our study is our small sample size. However, we have shown that minimal invasive techniques for LPND are safe, feasible and able to achieve adequate nodal clearance with no local recurrence in our short term follow up. CRT is inadequate in completely eradicating lateral metastasis and there are still technical limitations in accurately diagnosing persistent disease post CRT. Pre-CRT lymph node size is a reliable predictor of metastasis, and a nodal size of 1cm or more is highly suggestive of metastasis. LPND in such cases may confer a benefit in local control or even survival outcome. Treatment of lateral pelvic lymph node disease in low rectal cancer is still a subject of debate but a combination of CRT and LPND may be the optimal option. Further randomized control trials are needed to evaluate and answer this question.

Despite chemoradiation, pelvic lymph node recurrence rates are still significant. Performing lateral pelvic lymph node dissection (LPND) is increasingly being acknowledged to be able to reduce pelvic recurrence rates in patients with rectal cancer. However, it is difficult to select and predict which patients have metastatic disease in their lateral pelvic lymph nodes (LPLN).

LPND has an important role in complete oncological clearance to improve outcomes for patients with rectal cancer. Performing it safely using minimally invasive techniques(MIS) has further benefits for patients.

To present the characteristics and outcomes of our patients who underwent LPND, including lymph node characteristics which may help to predict lymph node involvement. Also, to demonstrate the safety and feasibility of performing the procedure using minimally invasive techniques.

Ethics approval was sought for this study. Clinico-pathological characteristics, perioperative variables and post-operative outcomes were analyzed retrospectively. Further analysis of the LPLN was performed, comparing their size against the final pathological outcomes.

Our findings show that there is minimal morbidity despite all procedures being performed using minimally invasive techniques. A lateral pelvic lymph node size of 1cm or more has a higher probability of metastasis. However, more research and data are needed to be analyzed to evaluate this size criterion for accuracy in predicting lymph node metastases.

In conclusion, lateral pelvic lymph node disease was shown to be inadequately treated with neoadjuvant therapy. LPND using MIS techniques is safe and feasible. LPLN that are 10mm or larger have a significant chance of having metastatic disease. However, this is a small series and further data is needed to improve the selection of patients for LPND.

Further research into this field should include larger and more extensive data sets to evaluate the size criteria that most accurately predicts lateral pelvic lymph node positivity. It may also reveal other variables that may assist in selecting patients that require LPND. We also wish to highlight the benefits of using the DaVinci Robot platform for this procedure, given its stability and maneuverability in a narrow space.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Singapore

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Yu B S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A E-Editor: Liu MY

| 1. | Fujita S, Mizusawa J, Kanemitsu Y, Ito M, Kinugasa Y, Komori K, Ohue M, Ota M, Akazai Y, Shiozawa M, Yamaguchi T, Bandou H, Katsumata K, Murata K, Akagi Y, Takiguchi N, Saida Y, Nakamura K, Fukuda H, Akasu T, Moriya Y; Colorectal Cancer Study Group of Japan Clinical Oncology Group. Mesorectal Excision With or Without Lateral Lymph Node Dissection for Clinical Stage II/III Lower Rectal Cancer (JCOG0212): A Multicenter, Randomized Controlled, Noninferiority Trial. Ann Surg. 2017;266:201-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 336] [Article Influence: 42.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Kim TH, Jeong SY, Choi DH, Kim DY, Jung KH, Moon SH, Chang HJ, Lim SB, Choi HS, Park JG. Lateral lymph node metastasis is a major cause of locoregional recurrence in rectal cancer treated with preoperative chemoradiotherapy and curative resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:729-737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Akiyoshi T, Ueno M, Matsueda K, Konishi T, Fujimoto Y, Nagayama S, Fukunaga Y, Unno T, Kano A, Kuroyanagi H, Oya M, Yamaguchi T, Watanabe T, Muto T. Selective lateral pelvic lymph node dissection in patients with advanced low rectal cancer treated with preoperative chemoradiotherapy based on pretreatment imaging. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:189-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kaur H, Ernst RD, Rauch GM, Harisinghani M. Nodal drainage pathways in primary rectal cancer: anatomy of regional and distant nodal spread. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2019;44:3527-3535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ueno M, Oya M, Azekura K, Yamaguchi T, Muto T. Incidence and prognostic significance of lateral lymph node metastasis in patients with advanced low rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2005;92:756-763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yano H, Moran BJ. The incidence of lateral pelvic side-wall nodal involvement in low rectal cancer may be similar in Japan and the West. Br J Surg. 2008;95:33-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sugihara K, Kobayashi H, Kato T, Mori T, Mochizuki H, Kameoka S, Shirouzu K, Muto T. Indication and benefit of pelvic sidewall dissection for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1663-1672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 314] [Cited by in RCA: 337] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kusters M, Slater A, Muirhead R, Hompes R, Guy RJ, Jones OM, George BD, Lindsey I, Mortensen NJ, Cunningham C. What To Do With Lateral Nodal Disease in Low Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer? A Call for Further Reflection and Research. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60:577-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kusters M, Marijnen CA, van de Velde CJ, Rutten HJ, Lahaye MJ, Kim JH, Beets-Tan RG, Beets GL. Patterns of local recurrence in rectal cancer; a study of the Dutch TME trial. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010;36:470-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 244] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Akiyoshi T, Watanabe T, Miyata S, Kotake K, Muto T, Sugihara K; Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum. Results of a Japanese nationwide multi-institutional study on lateral pelvic lymph node metastasis in low rectal cancer: is it regional or distant disease? Ann Surg. 2012;255:1129-1134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Georgiou P, Tan E, Gouvas N, Antoniou A, Brown G, Nicholls RJ, Tekkis P. Extended lymphadenectomy versus conventional surgery for rectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:1053-1062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kobayashi H, Mochizuki H, Kato T, Mori T, Kameoka S, Shirouzu K, Sugihara K. Outcomes of surgery alone for lower rectal cancer with and without pelvic sidewall dissection. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:567-576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Suzuki K, Muto T, Sawada T. Prevention of local recurrence by extended lymphadenectomy for rectal cancer. Surg Today. 1995;25:795-801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ogura A, Konishi T, Cunningham C, Garcia-Aguilar J, Iversen H, Toda S, Lee IK, Lee HX, Uehara K, Lee P, Putter H, van de Velde CJH, Beets GL, Rutten HJT, Kusters M; Lateral Node Study Consortium. Neoadjuvant (Chemo)radiotherapy With Total Mesorectal Excision Only Is Not Sufficient to Prevent Lateral Local Recurrence in Enlarged Nodes: Results of the Multicenter Lateral Node Study of Patients With Low cT3/4 Rectal Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:33-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Akasu T, Sugihara K, Moriya Y. Male urinary and sexual functions after mesorectal excision alone or in combination with extended lateral pelvic lymph node dissection for rectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:2779-2786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kim HJ, Choi GS, Park JS, Park SY, Cho SH, Lee SJ, Kang BW, Kim JG. Optimal treatment strategies for clinically suspicious lateral pelvic lymph node metastasis in rectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:100724-100733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |