Published online Apr 27, 2020. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v12.i4.171

Peer-review started: December 30, 2019

First decision: February 23, 2020

Revised: February 24, 2020

Accepted: March 26, 2020

Article in press: March 26, 2020

Published online: April 27, 2020

Processing time: 114 Days and 21.7 Hours

Gastric subepithelial lesions are frequently encountered during endoscopic examinations, and the majority of them are small and asymptomatic. Among these lesions, gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are the major concern for patients and clinicians owing to their malignant potentials. Although previous guidelines suggested periodic surveillance for such small (≤ 20 mm) lesions, several patients and clinicians have still requested or prescribed repeated examinations or radical resection, posing extra medical burdens and risks.

To describe the clinical course of suspected small gastric GISTs and provide further evidence for surveillance strategy for tumor therapy.

This single-center, retrospective study was conducted at West China Hospital, Sichuan University. Consecutive patients with suspected small gastric GISTs were reviewed from November 2004 to November 2018. GIST was suspected according to endoscopic ultrasonography features: hypoechoic lesions from muscularis propria or muscularis mucosa. Eligible patients with suspected small (≤ 20 mm) GISTs were included for analysis. Patients’ demographic data, lesions’ characteristics, and follow-up medical records were collected.

A total of 383 patients (male/female, 121/262; mean age, 54 years) with 410 suspected small gastric GISTs (1 lesion in 362 patients, 2 lesions in 16, 3 lesions in 4, and 4 lesions in 1) were included for analysis. The most common location was gastric fundus (56.6%), followed by body (29.0%), cardia (12.2%), and antrum (2.2%). After a median follow-up of 28 mo (interquartile range, 16-48; range, 3-156), 402 lesions (98.0%) showed no changes in size, and size of 8 lesions (2.0%) was increased (mean increment, 10 mm). Of the 8 lesions with size increment, endoscopic or surgical resection was performed in 6 patients (5 GISTs and 1 leiomyoma). For other 2 remaining patients, unroofing biopsy or endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration was carried out (2 GISTs), while no further change in size was noted over a period of 62-64 mo.

The majority of suspected small (≤ 20 mm) gastric GISTs had no size increment during follow-up. Regular endoscopic follow-up without pathological diagnosis may be highly helpful for such small gastric subepithelial lesions.

Core tip: This retrospective study submitted by Ye LS et al describes the clinical course of suspected small (≤ 20 mm) gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the stomach, in which the majority of lesions (98%, 402/410) had no size increment during a median follow-up of 28 mo (interquartile range, 16-48; range, 3-156), and the size of only 8 lesions (2.0%, 8/410) was increased (mean increment, 10 mm). Our findings may provide further evidence that surveillance strategy may be helpful for such small gastric subepithelial lesions.

- Citation: Ye LS, Li Y, Liu W, Yao MH, Khan N, Hu B. Clinical course of suspected small gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the stomach. World J Gastrointest Surg 2020; 12(4): 171-177

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v12/i4/171.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v12.i4.171

Gastric subepithelial lesions are frequently encountered, with a frequency of about 0.36% during routine upper endoscopies[1]. With increased endoscopic and radiological utilization, such lesions are becoming increasingly prevalent. Although the majority of these lesions are small and asymptomatic, they can cause bleeding, obstructive symptoms, and also carry malignant potentials. The most common subepithelial lesions detected by endoscopists are gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), leiomyomas, lipomas, granular cell tumors, pancreatic rests, and carcinoid tumors. Among them, GISTs remain as one of the major concerns for patients and clinicians because of their potential malignancy. Although previous guidelines have recommended that periodic surveillance for small (less than 20 mm) GISTs without high-risk endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) features is reasonable since malignant evolution is uncommon[2-4], several patients remain extremely worried, and request repeated endoscopic examinations or radical resection for their accidentally detected small gastric subepithelial lesions, posing extra medical burdens and risks. In addition, several clinicians prefer to perform endoscopic or surgical resection for these patients because of patients’ strong demands and the potential malignancy of lesions, which is blameless indeed, while may put those patients at great medical risks. Although several studies[5,6] demonstrated a low rate of size increment in patients with subepithelial lesions of the upper gastrointestinal tract, investigations involving only suspected gastric GISTs are limited; optimal follow-up interval for such lesions remained uncertain[2,4,7]. Therefore, in the present study, we described the clinical course of suspected small gastric GISTs, and our results may provide further evidence for surveillance strategy for tumor therapy.

This is a single-center, retrospective study conducted at West China Hospital, Sichuan University (Chengdu, China). The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of West China Hospital, Sichuan University (Chengdu, China).

From November 2004 to November 2018, all patients with suspected small (≤ 20 mm) gastric GIST were retrospectively reviewed at West China Hospital, Sichuan University. The diagnosis of GIST was suspected according to EUS characteristics[8,9], which were hypoechoic lesions (with or without homogeneous echo and well-defined margins) from muscularis propria or muscularis mucosa. Patients who underwent endoscopic or surgical resection after initial assessment owing to patients’ demands or high-risk EUS features, or patients who lost follow-up after initial endoscopic assessment were excluded.

All the examinations were performed by experienced endoscopists (each with experience of ≥ 1000 endoscopic examinations). Miniprobe EUS examination was performed on all patients to measure the exact size of lesions and for differential diagnosis. Radial or linear EUS was selected when miniprobe EUS could not clearly show the details of lesions. High-risk EUS features included irregular border, cystic spaces, ulceration, echogenic foci, and heterogeneity. Specimens were obtained by unroofing biopsy, EUS-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA), or resection, when lesions increased in size or patients strongly requested.

Patients with suspected GISTs less than 10 mm in size were recommended to receive endoscopic follow-up every 2 to 3 years, while patients with suspected GISTs of 10-20 mm in size were recommended to undergo endoscopic follow-up every 1 to 2 years. Endoscopic or surgical resection was planned if the lesion increased in size or became ulcerative, or when the patient strongly refused continual surveillance.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 25.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, United States). Continuous data were described as mean ± SD; range or median [interquartile range (IQR); range] according to their distribution. Categorical data were described as rate or proportion. The Student’s t-test, the Mann–Whitney U test, the χ2 test, or Fisher’s exact test was used accordingly. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

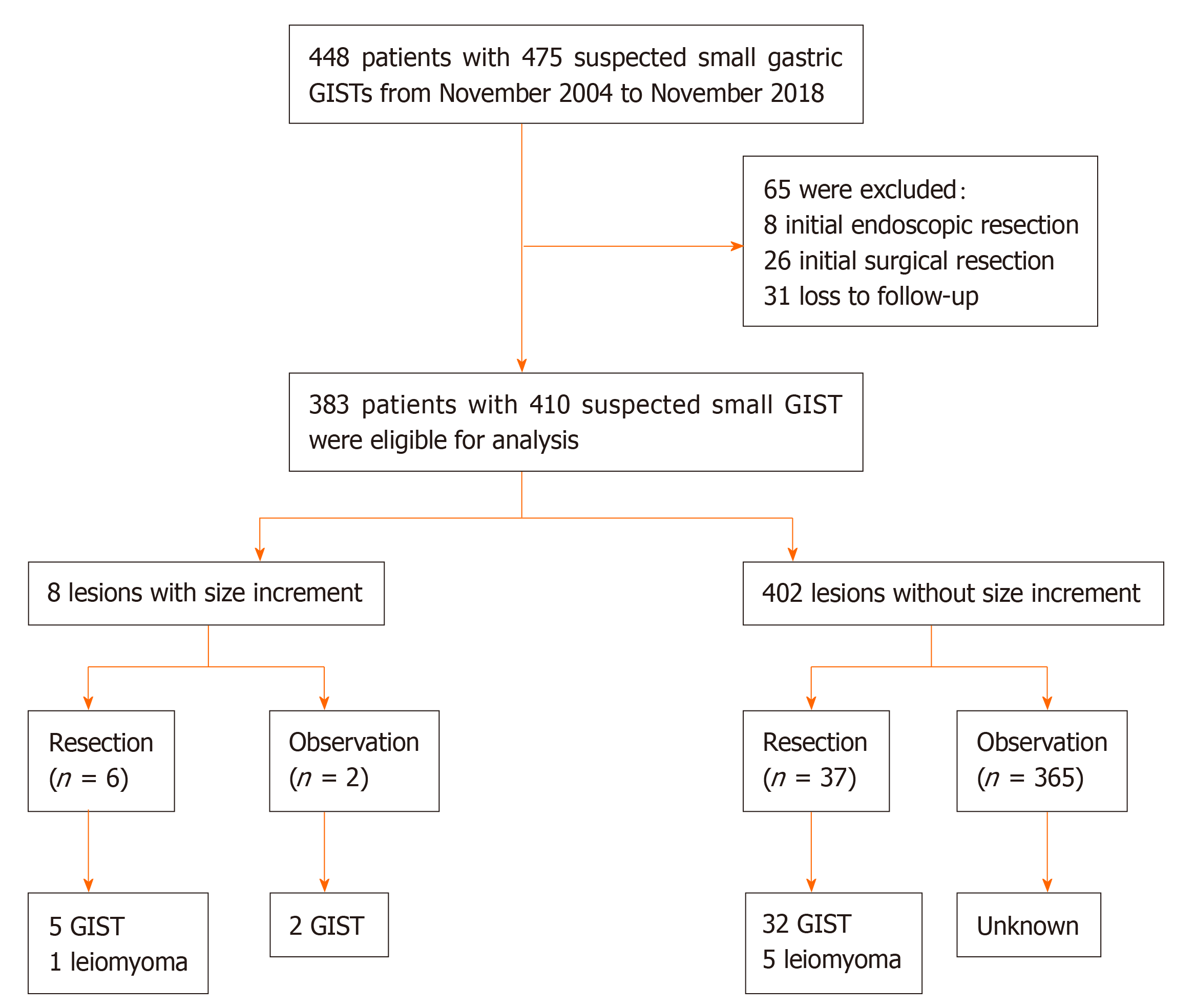

A total of 448 patients with 475 suspected small (≤ 20 mm) gastric GISTs were retrospectively reviewed, and 383 patients with 410 lesions were eligible for final analysis (Figure 1 and Table 1). The mean age of the 383 patients was 54 years (SD, 10; range, 23-80), and the male-to-female ratio was 1:2.2 (121/262). The majority of patients (94.5%, 362/383) had a single lesion, 16 patients (4.2%) had 2 lesions, 4 patients (1.0%) had 3 lesions, and 1 patient (0.3%) had 4 lesions. The median initial size of these lesions was 7 mm (IQR, 6-10; range, 3-20). The most common location was gastric fundus [232 lesions (56.6%)], followed by body [119 lesions (29.0%)], cardia [50 lesions (12.2%)], and antrum [9 lesions (2.2%)].

| All lesions | Lesions without size increment | Lesions with size increment | P value | |

| Patients, n1 | 383 | 375 | 8 | - |

| Age, yr2 | 54 (10; 23-80) | 54 (10; 23-80) | 57 (16; 31-74) | 0.5724 |

| Sex, male/female, n | 121/262 | 115/260 | 6/2 | 0.0145 |

| Lesions, n1 | 410 (100%) | 402 (98.0%) | 8 (2.0%) | - |

| Distribution, n | 0.3665 | |||

| Single lesion | 362 (94.5%) | 355 (94.7%) | 7 (87.5%) | |

| Two lesions | 16 (4.2%) | 15 (4.0%) | 1 (12.5%) | |

| Three lesions | 4 (1.0%) | 4 (1.1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Four lesions | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Location, n | 0.1395 | |||

| Cardia | 50 (12.2%) | 49 (12.2%) | 1 (12.5%) | |

| Fundus | 232 (56.6%) | 230 (57.2%) | 2 (25.0%) | |

| Body | 119 (29.0%) | 114 (28.4%) | 5 (62.5%) | |

| Antrum | 9 (2.2%) | 9 (2.2%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Initial size, mm3 | 7 (6-10; 3-20) | 7 (6-10; 3-20) | 12 (9-13; 4-15) | 0.0186 |

| Less than 10 mm, n | 291 (71.0%) | 289 (71.9%) | 2 (25.0%) | 0.0095 |

| 10-20 mm, n | 119 (29.0%) | 113 (28.1%) | 6 (75.0%) | |

| Follow-up, mo3 | 28 (16-48; 3-156) | 27 (15-47; 3-156) | 60 (46-83; 41-146) | 0.0016 |

Specimens were obtained from 45 of 410 lesions, by unroofing biopsy in 1 lesion, EUS-FNA in 1, endoscopic resection in 29, and surgical resection in 14.

Final diagnosis was made in all the 45 patients, including 39 GISTs and 6 leiomyomas.

During a median follow-up of 28 mo (IQR, 16-48; range, 3-156), 402 lesions (98.0%) showed no changes in size, and size of 8 lesions (2.0%) was increased (mean increment was 10 mm; SD, 3; range, 7-14) (Table 1).

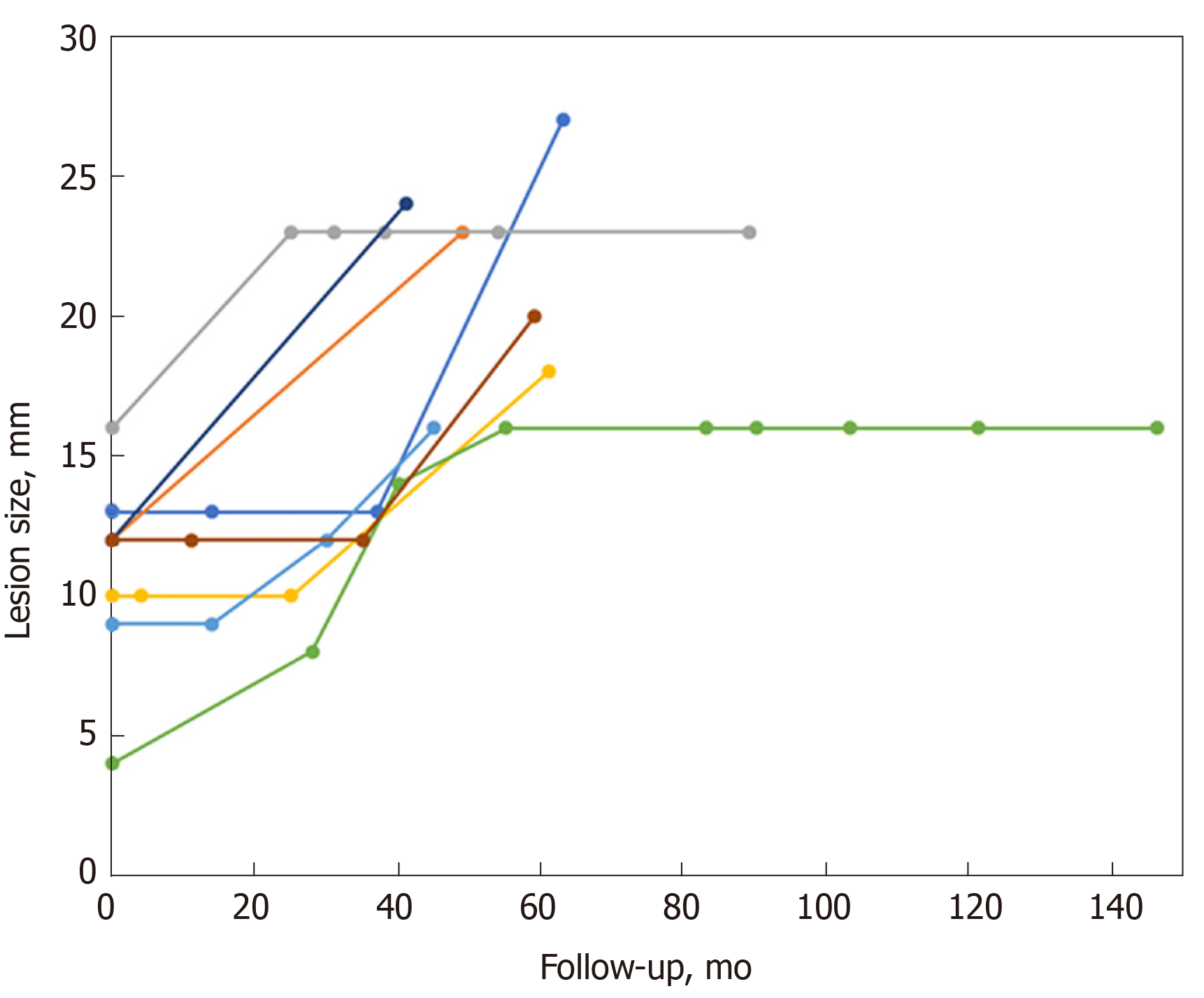

Of these 8 lesions with increased size, endoscopic or surgical resection was performed in 6 patients, which revealed 5 GISTs (3 with low risk of malignancy, and 2 with intermediate risk of malignancy) and 1 leiomyoma. For other 2 remaining patients, unroofing biopsy or EUS-FNA was conducted, while no further change in size was noted over a period of 62-64 mo (Figure 2).

In the present study, we found that there was no size increment in the majority of small (≤ 20 mm) suspected gastric GISTs (98.0%, 402/410), and the size of only 8 lesions (2.0%) was increased during a median follow-up of 28 mo (IQR, 16-48; range, 3-156). Our findings are consistent with those reported previously[5,6,10]. Imaoka et al[5] showed that only 2 of 132 subepithelial lesions of the stomach (1.51%) had size increment during 5 years of endoscopic follow-up. Kim et al[6] followed-up 989 subepithelial lesions of the stomach (≤ 30 mm) over a median period of 24 mo (range, 3-123 mo), and noted that only 81 tumors (8.19%) had significant increment in size. Song et al[10] also reported no size increment in 613 of 640 small (≤ 35 mm) subepithelial lesions of the upper gastrointestinal tract (95.78%) over a mean follow-up of 47.3 mo (range, 6-118 mo). The difference between these reports and the present study is related to the definition of small lesions. We defined small lesions as lesions ≤ 20 mm in size, since lesions larger than 20 mm are commonly recommended to undergo resection, and lesions with size of ≤ 20 mm are taken as very low risk of recurrence[4], which seems to be more reasonable. The current study provided further evidence that the majority of small (≤ 20 mm in size) suspected gastric GISTs remained stable during follow-up, and periodic surveillance without pathological diagnosis was found to be reasonable.

It is also highly important to indicate optimal follow-up interval for such suspected small gastric GISTs. Recommendations from different countries and associations were found remarkably different[2,4,7]. The European Society for Medical Oncology and the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy suggested initial EUS after 3 mo of detection, and then annual follow-up; the National Comprehensive Cancer Network highly recommended 6-12 mo of follow-up interval; the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society demonstrated that 1-2 years of follow-up interval is enough for such small lesions; the recently published French guideline recommended EUS follow-up at 6 and 18 mo, and then every 2 years. However, as shown in Table 1, lesions with larger initial size may be more likely to increase during follow-up. Such phenomenon has already been reported by Kim et al[6] and Song et al[10]. Therefore, from economic point of view, we suggested that different follow-up intervals may be better for lesions with different initial sizes. Our strategy that 2- to 3-year interval for lesions less than 10 mm and 1- to 2-year interval for lesions with size of 10-20 mm, seems to be advisable.

In the present study, all the patients underwent initial and follow-up EUS for lesion assessment. Although EUS has been suggested as the gold-standard in distinguishing intramural lesions from extramural compression, its role in determining lesions with size of less than 10 mm is limited[11-13]. Considering that exophytic lesions may be underestimated under endoscopic view, initial EUS assessment regardless of lesion size seems to be reasonable, while routine EUS follow-up should not be used despite patients’ preference.

We also demonstrated that lesions with size increment did not increase constantly over time (Figure 2). In 2010, Lim et al[14] reported that continual size increment was not detected in lesions with size increments. In addition, Kim et al[6] found no consistent growth patterns for small gastric subepithelial lesions. These results revealed that size increment during follow-up may not be taken as a catastrophe into consideration, and continual follow-up may also be an alternative for selective patients.

There were several limitations in this study. First, it was a retrospective study, thus the modality and interval of follow-up could not be standardized. Some patients with lesions less than 10 mm in size strongly requested repeated examinations or even radical resection although no size increment was noted. Second, underlying mucosal change was not discussed in this study although it has been reported to be a risk factor for size increment[10]. This is mainly because only 2 lesions had underlying mucosal ulceration during follow-up (1 lesion with size increment and 1 lesion without size increment, respectively). Since size of lesion is one of the most important factors (the other one is mitotic index) for prediction of the risk of recurrence for localized gastric GIST[4], assessment of only lesion size for suspected gastric GIST is reasonable.

In conclusion, the majority of small (≤ 20 mm) suspected gastric GISTs had no size increment during follow-up. Regular endoscopic follow-up may be therefore helpful for such small gastric subepithelial lesions. From economic point of view, different follow-up intervals should be proposed for lesions with size of less than 10 mm and those with size of 10-20 mm.

Gastric subepithelial lesions are frequently encountered during endoscopic examinations, and the majority of them are small and asymptomatic. Among these lesions, gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are the major concern for patients and clinicians owing to their malignant potentials. Although previous guidelines suggested periodic surveillance for such small (≤ 20 mm) lesions, several patients and clinicians have still requested or prescribed repeated examinations or radical resection, posing extra medical burdens and risks.

Although several studies demonstrated a low rate of size increment in patients with gastric subepithelial lesions, there were limited investigations involving only suspected small gastric GISTs; the optimal follow-up interval for such lesions remains uncertain.

In this retrospective study, we aimed to describe the clinical course of suspected small gastric GISTs, and to provide further evidence for surveillance strategy for tumor therapy.

Consecutive patients with suspected small (≤ 20 mm) gastric GISTs from November 2004 to November 2018 at West China Hospital were retrospectively reviewed. GIST was suspected according to endoscopic ultrasonography features: hypoechoic lesions from muscularis propria or muscularis mucosa. Eligible patients with suspected small GISTs were included for analysis. Patients’ demographic data, lesions’ characteristics, and follow-up medical records were collected.

A total of 383 patients (male/female, 121/262; mean age, 54 years) with 410 suspected small gastric GISTs (1 lesion in 362 patients, 2 lesions in 16, 3 lesions in 4, and 4 lesions in 1) were included for analysis. The most common location was gastric fundus (56.6%), followed by body (29.0%), cardia (12.2%), and antrum (2.2%). After a median follow-up of 28 mo (interquartile range, 16-48; range, 3-156), 402 lesions (98.0%) showed no changes in size, and 8 (2.0%) lesions increased in size (mean increment, 10 mm). Of the 8 lesions with size increment, endoscopic or surgical resection was performed in 6 patients (5 GISTs and 1 leiomyoma). For other 2 remaining patients, unroofing biopsy or endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration was carried out (2 GISTs), while no further change in size was noted over a period of 62-64 mo.

The majority of suspected small (≤ 20 mm) gastric GISTs had no size increment during follow-up. Regular endoscopic follow-up without pathological diagnosis may be highly helpful for such small gastric subepithelial lesions.

Prospective study involving specific follow-up period for lesions with different initial size may be better to develop an economic strategy for surveillance.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Caputo D, Yoshinaga S S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: A E-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Papanikolaou IS, Triantafyllou K, Kourikou A, Rösch T. Endoscopic ultrasonography for gastric submucosal lesions. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;3:86-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Demetri GD, von Mehren M, Antonescu CR, DeMatteo RP, Ganjoo KN, Maki RG, Pisters PW, Raut CP, Riedel RF, Schuetze S, Sundar HM, Trent JC, Wayne JD. NCCN Task Force report: update on the management of patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8 Suppl 2:S1-41; quiz S42-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 826] [Cited by in RCA: 816] [Article Influence: 54.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | ESMO/European Sarcoma Network Working Group. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2014;25 Suppl 3:iii21-iii26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 256] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Landi B, Blay JY, Bonvalot S, Brasseur M, Coindre JM, Emile JF, Hautefeuille V, Honore C, Lartigau E, Mantion G, Pracht M, Le Cesne A, Ducreux M, Bouche O; «Thésaurus National de Cancérologie Digestive (TNCD)» (Fédération Francophone de Cancérologie Digestive (FFCD); Fédération Nationale de Centres de Lutte Contre les Cancers (UNICANCER); Groupe Coopérateur Multidisciplinaire en Oncologie (GERCOR); Société Française de Chirurgie Digestive (SFCD); Société Française de Radiothérapie Oncologique (SFRO); Société Française d’Endoscopie Digestive (SFED); Société Nationale Française de Gastroentérologie (SNFGE). Gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs): French Intergroup Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatments and follow-up (SNFGE, FFCD, GERCOR, UNICANCER, SFCD, SFED, SFRO). Dig Liver Dis. 2019;51:1223-1231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Imaoka H, Sawaki A, Mizuno N, Takahashi K, Nakamura T, Tajika M, Kawai H, Isaka T, Okamoto Y, Inoue H, Aoki M, Salem AA, Yamao K. Incidence and clinical course of submucosal lesions of the stomach. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:Ab167-Ab167. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Kim MY, Jung HY, Choi KD, Song HJ, Lee JH, Kim DH, Choi KS, Lee GH, Kim JH. Natural history of asymptomatic small gastric subepithelial tumors. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:330-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cho JW; Korean ESD Study Group. Current Guidelines in the Management of Upper Gastrointestinal Subepithelial Tumors. Clin Endosc. 2016;49:235-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chak A. EUS in submucosal tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:S43-S48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Eckardt AJ, Wassef W. Diagnosis of subepithelial tumors in the GI tract. Endoscopy, EUS, and histology: bronze, silver, and gold standard? Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:209-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Song JH, Kim SG, Chung SJ, Kang HY, Yang SY, Kim YS. Risk of progression for incidental small subepithelial tumors in the upper gastrointestinal tract. Endoscopy. 2015;47:675-679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Menon L, Buscaglia JM. Endoscopic approach to subepithelial lesions. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2014;7:123-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Reddymasu SC, Oropeza-Vail M, Pakseresht K, Moloney B, Esfandyari T, Grisolano S, Buckles D, Olyaee M. Are endoscopic ultrasonography imaging characteristics reliable for the diagnosis of small upper gastrointestinal subepithelial lesions? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:42-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Karaca C, Turner BG, Cizginer S, Forcione D, Brugge W. Accuracy of EUS in the evaluation of small gastric subepithelial lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:722-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lim YJ, Son HJ, Lee JS, Byun YH, Suh HJ, Rhee PL, Kim JJ, Rhee JC. Clinical course of subepithelial lesions detected on upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:439-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |