Published online Nov 27, 2020. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v12.i11.460

Peer-review started: July 30, 2020

First decision: September 17, 2020

Revised: September 30, 2020

Accepted: November 11, 2020

Article in press: November 11, 2020

Published online: November 27, 2020

Processing time: 118 Days and 2.6 Hours

Anastomotic stenosis (AS) after colorectal surgery was treated with balloon dilation, endoscopic procedure or surgery. The endoscopic procedures including dilation, electrocautery incision, or radial incision and cutting (RIC) were preferred because of lower complication rates than surgery and are less invasive. Endoscopic RIC has a greater success rate than dilation methods. Most reports showed that repeated RICs were needed to maintain patency of the anastomosis. We report that single session RIC was applied only to treatment-naive patients with AS.

Two female patients presented with AS. One patient had advanced rectal cancer and the other had a refractory stenosis following surgery for endometriosis at sigmoid colon. The endoscopic RIC procedure was performed as follows. A single small incision was carefully made to increase the view of the proximal colon and the incision was expanded until the surgical stapling line. Finally, we made a further circumferential excision with endoscopic knife along the inner border of the surgical staple line. At the end of the procedure, the standard colonoscope was able to pass freely through the widened opening. All patients showed improved AS after a single session of RIC without immediate or delayed procedure-related complications. Follow-up colonoscopy at 7 and 8 mo after endoscopic RIC revealed intact anastomotic sites in both patients. No treatment-related adverse events or recurrence of the stenosis was demonstrated during follow-up periods of 20 and 23 mo.

The endoscopic RIC may play a role as one of treatment options for treatment-naive AS with short stenotic lengths.

Core Tip: Currently, most clinicians prefer endoscopic procedures for the treatment of stenosis after colorectal anastomoses, including dilation, electrocautery incision, or radial incision and cutting (RIC), because they have lower complication rates than surgery and are less invasive. Here, we report the use of endoscopic RIC alone with single session for two patients who presented with treatment-naive anastomotic stenosis (AS) after colorectal anastomosis. The endoscopic RIC procedure may play a role as one of the treatment options for treatment-naive, central-type AS with short stenotic lengths and for AS confined to the mucosa and submucosa.

- Citation: Lee TG, Yoon SM, Lee SJ. Endoscopic radial incision and cutting technique for treatment-naive stricture of colorectal anastomosis: Two case reports. World J Gastrointest Surg 2020; 12(11): 460-467

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v12/i11/460.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v12.i11.460

Gastrointestinal anastomotic stenosis (AS) is characterized by intestinal dysfunction and/or variable degrees of discomfort caused by narrowing of the lumen at the anastomotic site. Incidence rates of stenosis have been reported to range from 3% to 30% after colorectal, ileorectal, or coloanal anastomoses[1]. The cause of AS is not clear but risk factors may include neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, anastomotic leakage, diverting stoma, stapled anastomosis, tissue ischemia, inflammation, or surgical technique[2-4].

Several treatments for AS have been introduced and include digital or instrumental dilatation, endoscopic ballooning, transanal strictureplasty, stapled transanal resection, self-expandable metal stents, abdominal redo-surgery, defunctioning colostomy, or endoscopic radial incision and cutting (RIC)[1,3-15]. Garcea et al[16] reported that balloon dilatation is occasionally necessary to perform repeated dilation combined with electrocautery resection to maintain normal bowel function. Currently, endoscopic treatments that include dilation, endoscopic electrocautery incision (EECI), and endoscopic RIC are preferred over surgery or instrumental dilatation. Good success and low complication rates have been reported for endoscopic balloon dilatation, but this method has limitations similar to transanal balloon dilatation[17]. The success rate was 98.4% for EECI alone or in combination with other modalities used for AS, and the recurrence rate was 6.0%[18]. EECI is more effective in treatment-naive than treatment-refractory AS. The RIC technique was introduced first as a treatment for refractory esophagogastric AS[19]. The RIC method was recently adopted by Osera et al[11] for refractory AS which occurred after bougie dilatation or balloon dilatation. In a comparison of success rate and post-procedural morbidity, EECI and RIC were superior to endoscopic balloon dilation[16].

To date, the majority of endoscopic RIC procedures have been used for treatment-refractory AS or in combination with dilation or argon plasma coagulation. Here, we report that using single session of the endoscopic RIC alone may be effective the treatment option for two patients who presented with treatment-naive AS after colorectal anastomosis.

Patient demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. We obtained informed consent from patients.

| Case | 1 | 2 |

| Age (yr)/Gender | 78/Female | 47/Female |

| Chief complaints before surgery | Hematochezia, constipation, tenesmus | Abdominal pain, constipation |

| Clinical symptoms at diagnosis | None | Abdominal distension, constipation |

| Comorbidity | HTN | Insomnia, mood disorder |

| Past history of abdominal surgery | None | TLH with BSO |

| Operation method | LAR | HAR |

| Temporary ileostomy | Yes | No |

| Postoperative complication | None | None |

| Pathology | Adenocarcinoma | Endometriosis |

| Stage | pT3N0M0 | |

| Adjuvant therapy | None | None |

Case 1: A 78-year-old woman underwent low anterior resection with diverting ileostomy for advanced rectal cancer 5 mo ago. When the patient visits for ileostomy closure, we found an AS on the digital rectal examination.

Case 2: A 46-year-old woman presented with abdominal pain and constipation 7 mo ago. On October, 2017, the patient underwent laparoscopic total hysterectomy with bilateral oophorectomy due to the same symptoms and dysmenorrhea 1 years ago. At that time, pathologic examination revealed 4 cm sized endometrioma. On January, 2018, she has not been still improved symptoms including constipation, abdominal pain, and distension. Colonoscopy revealed luminal stenosis without intrinsic lesions at 20-25 cm from the anal verge. Abdominopelvic computed tomography (CT) revealed segmental edematous wall thickening of the sigmoid colon. On May, 2018, the patient underwent laparoscopic-assisted sigmoidectomy for severe colon stenosis due to endometriosis. On September, 2018, the same symptoms occurred after the operation.

Case 1: The patient received medications for hypertension for ten years. She was on oral anti-hypertensive drug including losartan and was in good control. She underwent low anterior resection with diverting ileostomy 5 mo ago.

Case 2: The patient took medication for insomnia and moderate depressive disorder including venlafaxine and lorazepam for two years. She underwent total hysterectomy with bilateral salphingo-oophorectomy for endometrioma 3 years ago, and laparoscopic-assisted sigmoidectomy for colon stricture cause by severe endometriosis 7 mo ago.

They have no family history.

Case 1: On digital rectal examination, a narrowed lumen where the finger was not able to pass through the anastomotic site was palpable.

Case 2: The patient was hemodynamically stable, and there was no tenderness on her abdomen, although he complained of slight abdomen discomfort.

Two patients had all within normal limits in the results of routine laboratory tests including routine blood examination, blood biochemistry, routine urine examination, fecal occult blood, and tumor markers.

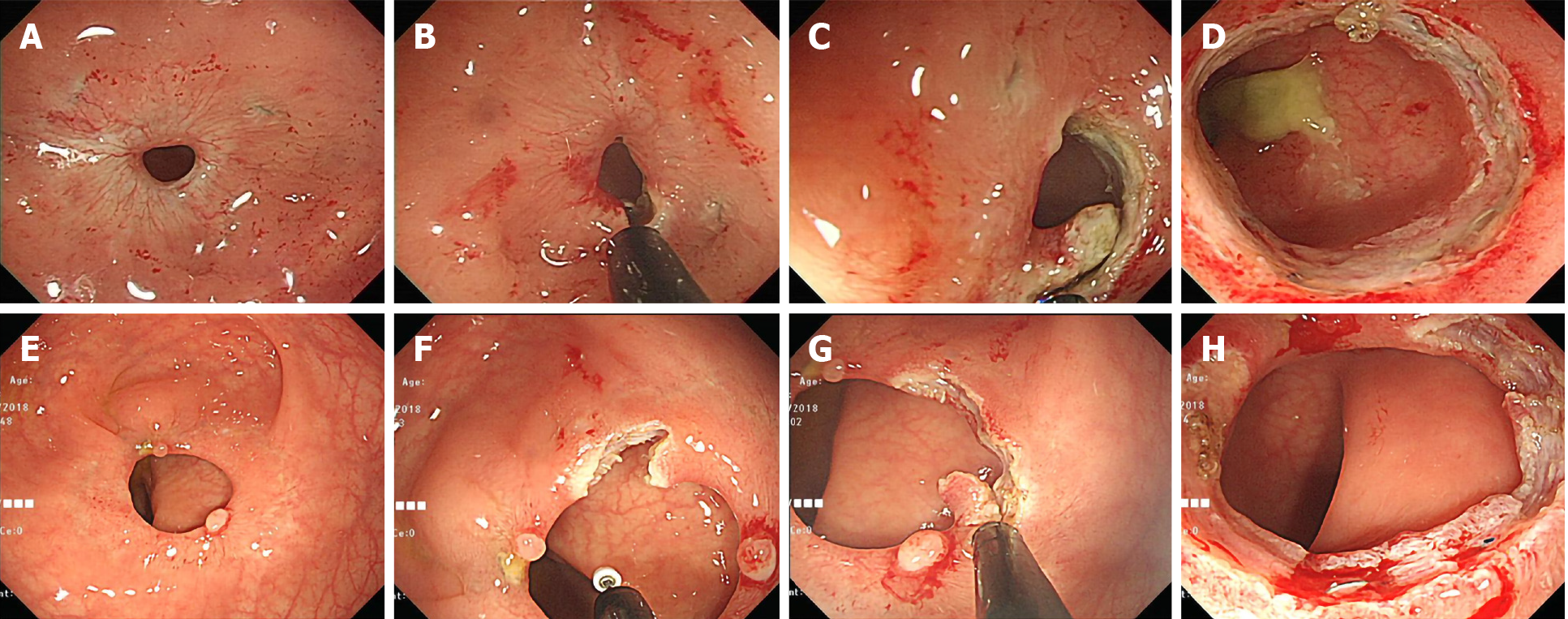

Case 1: Colonoscopy revealed an AS at 4 cm from the anal verge (Figure 1A).

Case 2: Colonoscopy revealed an AS at 12 cm from the anal verge (Figure 1E).

Case 1: The rectal tumor was an ulcerofungating mass measuring 7 cm × 6.7 cm × 4 cm in size. Pathologic examination showed a moderated differentiated adenocarcinoma of the rectum that invaded the pericolorectal fat. There was no lymph node metastasis within the resected 22 lymph nodes (pT3N0M0, Stage IIA). The tumor has no lymphovascular and perineural invasion. After RIC, pathologic examination revealed fibrotic granulation tissue.

Case 2: The extrinsic colon mass was diagnosed with endometriosis. After RIC, pathologic examination showed inflamed granulation tissue with hyperplastic colonic epithelium.

The final diagnosis of all presented cases was AS.

The patients received midazolam or propofol as sedation for the colonoscopy procedure. The RIC technique used an insulation-tipped electrosurgical knife (ITknife2, KD-611L; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) for cutting the stenotic tissues. The Erbe VIO® 300D electrosurgical system (Erbe Elektromedizin GmbH, Tubingen, Germany) was set to the Endo Cut® Q mode using Effect setting 2 (30 W) to create the incisions and remove the scar tissue. The RIC procedure was performed as follows. First, a small incision was carefully made to increase the view of the proximal colon. Next, the incision was expanded until the surgical stapling line at the anastomotic site was exposed. Finally, we made a further circumferential excision with the ITknife2 along the inner border of the surgical staple line (Figure 1). At the end of the procedure, the standard colonoscope was able to pass freely through the widened opening. The RIC treatment was considered successful if the colonoscope could pass through the stenotic area or the stapling line was exposed.

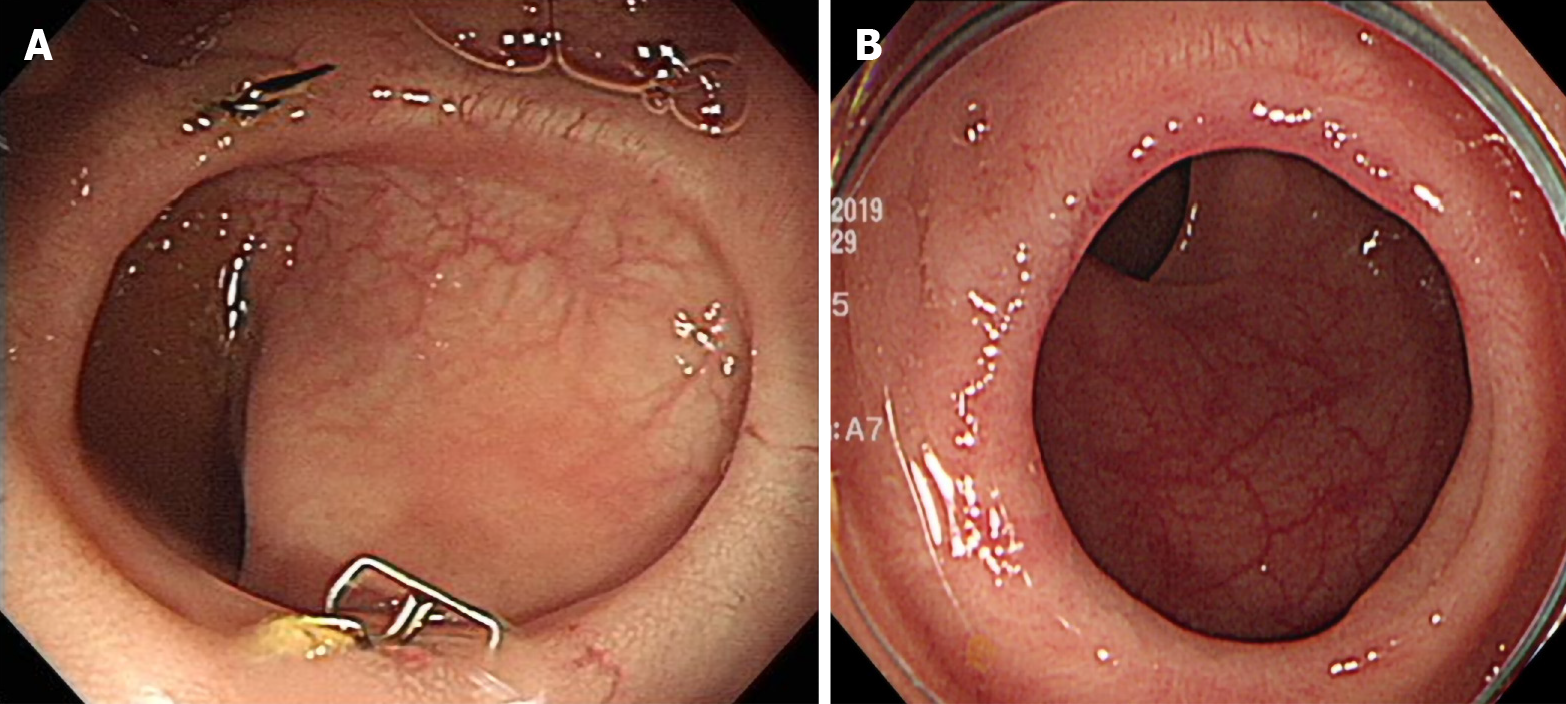

The results of the RIC procedure and the colonoscopic findings are shown in Table 2. Both patients were treatment-naive for AS and underwent RIC used a single incision. There were no complications such as bleeding, perforation, fever, and abdominal pain. The ileostomy was closed 2 mo later for case 1, and there were no disturbances in this patient’s stool passage. There was a remarkable improvement in the stenosis in these patients with no recurrence observed by colonoscopy after 7 and 8 mo follow-up (Figure 2). The patients had no AS related symptoms at 20 and 23 mo after the RIC procedure.

| Patient | 1 | 2 |

| Duration from surgery to endoscopic RIC (mo) | 3 | 4 |

| Sedative drugs | Midazolam | Midazolam, propofol |

| Distance between AS and anal verge (cm) | 4 | 12 |

| Diameter of AS (mm) | 2 | 4 |

| Ileostomy status at time of endoscopic RIC | Yes | No |

| Pretreatment before RIC | None | None |

| Procedure time (min) | 12 | 20 |

| Major complications | None | None |

| Post-procedural hospital stays (d) | 3 | 2 |

| Follow-up after endoscopic RIC (mo) | 20 | 23 |

Many treatment methods for AS have been introduced, but consensus of treatment has not yet been established. Kraenzler et al[5] reported that 99 procedures were performed in 50 patients with AS. They performed digital, instrumental, or endoscopic dilatation, transanal strictureplasty, transanal circular stapler resection, or transabdominal redo-anastomosis. Success rates were 36%, 40% and 20% for digital, instrumental, and endoscopic dilatation procedures, respectively. These rates were lower than that observed for operative methods such as circular stapler resection (64%), strictureplasty (89%), and transabdominal redo-anastomosis (73%). Despite the higher success rate, surgical procedures carry the risk of postoperative morbidities including perforation peritonitis, pelvic sepsis, incisional hernia, and potential need for a permanent colostomy[1,5,7]. Rates of complications after transabdominal surgical procedures ranged from 7.4% to 18%, which are higher than complication rates for endoscopic or instrumental dilatation (from 0% to 3%), transanal strictureplasty, stenting, and endoscopic RIC[5,7].

Recently, treatments for AS have become more minimally invasive by using endoscopic techniques and transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS). Endoscopic techniques for AS were effective, feasible, and safe but had a high re-stenosis rate of up to 20%[20]. Nepal et al[21] performed the RIC method for rectal stricture using a TAMIS approach. TAMIS may provide a wider operative field than endoscopy and allow a more complete resection because the surgeon can easily repair a defect in the muscular layer if a luminal perforation has occurred during surgery. However, TAMIS may only be useful for anastomoses in the rectum or distal sigmoid colon because the inability of surgical devices to reach strictures beyond the rectosigmoid colon, and fail to insert transanal access device through the anus in very low-lying anastomosis. The endoscopic RIC in comparison with TAMIS has the advantage that it can be performed in any position of the colon. Asayama et al[13] performed endoscopic RIC for AS of the transverse colon and sigmoid colon. In our cases, one patient underwent endoscopic RIC for AS at 12 cm from the anal verge.

As one of the endoscopic treatments, EECI technique only performs cut and incision on the stenotic site. The EECI technique is often used in combination with balloon dilation, argon plasma coagulation, or adjunctive corticosteroid injection[18]. There were no major adverse events reported for EECI. During the EECI procedure, it is important to create an endoscopic incision and direction based on the length, depth, and eccentric or central type of stenosis. The endoscopic RIC is a supplement to EECI that requires additional methods. Some authors described the endoscopic RIC technique, which involved multiple radial incisions and then cutting the stenotic tissue using an endoscopic knife along the lumen[11-14].

As shown in Table 3, endoscopic RIC has good results and no major complication such as bowel perforation, bleeding, and peritonitis. To improve the outcomes, the indication criteria for the endoscopic RIC technique are important. Before endoscopic RIC, abdominopelvic CT scan, barium enema, or colonoscopy should be performed to check the proximal bowel patency, locoregional recurrence, and length or depth of the AS. In the case of AS with complete obstruction, needle puncture is helpful to determine the first puncture site during the procedure and the length of the stenosis. The treatment modality for AS can be determined by location. When AS is located far from the anal verge, endoscopic ballooning or RIC, incision and transabdominal re-anastomosis is recommended. However, if AS is located near the anal verge, transanal revision, ballooning, bougination, or TAMIS is preferred. To date, only 14 patients have been treated for AS with endoscopic RIC alone. Osera et al[11] reported failure to treat AS in 2 of 7 patients because stenoses were located near the anal sphincter. These authors suggested that AS near the anal sphincter might tend to be refractory. Nine patients including our cases were successfully treated and AS located far from the anal verge. Schlegel et al[7] showed that reoperation for AS was performed more frequently in the middle or lower rectum than the upper rectum. Endoscopic RIC may be more effective for colorectal than coloanal anastomosis. In our patients, we routinely perform digital rectal examination, abdominopelvic CT, and/or water-soluble contrast enema for anastomotic dehiscence prior to ileostomy takedown. These examinations can be helpful for establishing continuity with the proximal colon, and lengths of AS. Direct observation using an ultrathin endoscope through a small opening may be another feasible method, if the endoscope can pass through the narrowed site.

| Kawaguti et al[12] | Harada et al[14] | Osera et al[11] | Asayama et al[13] | Our study | |

| Number of the patient, n | 1 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 2 |

| Median age (yr), (range) | 67 | 62 (NA) | 66 (56-72) | 72 (65-76) | 62.5 (47-78) |

| Gender (male:female) | NA | 3:0 | 6:1 | 3:0 | 0:2 |

| Median interval from surgery to RIC (mo), (range) | NA | 7 (5-12) | 11 (5-44) | 21 (9-29) | 3.5 (3-4) |

| AS location | R | R | R | T, S, S | R |

| Temporary stoma at time of RIC, n | 1 | 1 | 3 | NA | 1 |

| Treatment naive AS, n | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Previous treatment of RIC, n | None | 3 | 7 | 1 | None |

| Bougie dilatation | NA | 5 | 0 | ||

| Endoscopic balloon dilatation | NA | 2 | 1 | ||

| Endoscopic RIC with single session, n | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Mean number of RIC sessions | 1 | 1.3 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 1 |

| Median procedure time (min), (range) | 12 | 69.5 (35-82) | 18 (7-34) | 22 (15-25) | 16 (12-20) |

| Major complication | None | None | None | None | None |

| Median post-procedural hospital stay (d), (range) | NA | 3.5 (3-4) | 3 (2-5) | 4 (2-5) | 2.5 (2-3) |

| Median follow-up after RIC (mo), (range) | 8 | 17 (3-33) | 27 (18-55) | 25 (5-34) | 21.5 (20-23) |

| Treatment after restenosis, n | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Treatment failure, n | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

Endoscopic RIC for AS may be more effective in treatment naive patients. Three of 14 patients were treatment naive AS, all patients treated with endoscopic RIC. However, 1 patient needed additional sessions for recurrent AS[11-14]. Jain et al[18] reported that treatment-naive patients had a higher early and long-term success rate than the treatment-refractory group. Another reason is that thick fibrotic tissue of refractory AS interferes with the discrimination of mucosal tissues. One technical tip from our cases is that the stapling line may be a good landmark for the cutting line, if the endoscopist is able to find the anastomotic staples during the procedure. The depth of excision during endoscopic RIC should maintain the muscular layer because the possibility of anastomotic failure, perforation, or peritonitis may be increased. Intraluminal sutures through the anus may be needed to prevent perforation, if the cutting surface involves the muscular layer. Cutting the stenotic tissue inside the stapling line reduces the risk of involving the muscular layer because the inner surface of the stapling line is covered with fibrotic tissue or granulated scar tissue. RIC can be easily applied in the central type of stenosis without deformation of the stapling line. If the patient has a stapling line deformity, the inner diameter may be narrowed and the colonoscope may not pass sufficiently after the RIC procedure. In our cases, both patients were treatment-naive and had a central type of stenosis, and the endoscopic RIC procedure with single session was successful in achieving stenosis dilation.

This report shows that the endoscopic RIC with single session is the successful management for treatment-naive AS. The patients had no procedure-related complications or recurrence during the follow-up periods. Due to the limitations of two cases study, large-scale clinical trials are needed to prove the feasibility, efficacy and safety of the endoscopic RIC as an initial treatment for such patients. We believe that future studies will reveal endoscopic RIC may be considered one of the treatment options for treatment-naive patients with a central type of AS, short lengths of AS, and AS that is confined to the mucosa and submucosa. Endoscopic RIC for treatment-naive AS may be feasible, effective, and safe regardless of the location of the AS.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: The Korean Society of Gastroenterology, No. 1-08-1162.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Harada K S-Editor: Huang P L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Luchtefeld MA, Milsom JW, Senagore A, Surrell JA, Mazier WP. Colorectal anastomotic stenosis. Results of a survey of the ASCRS membership. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:733-736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ferzoco LB, Raptopoulos V, Silen W. Acute diverticulitis. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1521-1526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sartori A, De Luca M, Fiscon V, Frego M; CANSAS study working group; Portale G. Retrospective multicenter study of post-operative stenosis after stapled colorectal anastomosis. Updates Surg. 2019;71:539-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Polese L, Vecchiato M, Frigo AC, Sarzo G, Cadrobbi R, Rizzato R, Bressan A, Merigliano S. Risk factors for colorectal anastomotic stenoses and their impact on quality of life: what are the lessons to learn? Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:e124-e128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kraenzler A, Maggiori L, Pittet O, Alyami MS, Prost À la Denise J, Panis Y. Anastomotic stenosis after coloanal, colorectal and ileoanal anastomosis: what is the best management? Colorectal Dis. 2017;19:O90-O96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Werre A, Mulder C, van Heteren C, Bilgen ES. Dilation of benign strictures following low anterior resection using Savary-Gilliard bougies. Endoscopy. 2000;32:385-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Schlegel RD, Dehni N, Parc R, Caplin S, Tiret E. Results of reoperations in colorectal anastomotic strictures. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1464-1468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nguyen-Tang T, Huber O, Gervaz P, Dumonceau JM. Long-term quality of life after endoscopic dilation of strictured colorectal or colocolonic anastomoses. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1660-1666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | McKee R, Pricolo VE. Stapled revision of complete colorectal anastomotic obstruction. Am J Surg. 2008;195:526-527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lamazza A, Fiori E, Schillaci A, Sterpetti AV, Lezoche E. Treatment of anastomotic stenosis and leakage after colorectal resection for cancer with self-expandable metal stents. Am J Surg. 2014;208:465-469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Osera S, Ikematsu H, Odagaki T, Oono Y, Yano T, Kobayashi A, Ito M, Saito N, Kaneko K. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic radial incision and cutting for benign severe anastomotic stricture after surgery for lower rectal cancer (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:770-773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kawaguti FS, Martins BC, Nahas CS, Marques CF, Ribeiro U, Nahas SC, Maluf-Filho F. Endoscopic radial incision and cutting procedure for a colorectal anastomotic stricture. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:408-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Asayama N, Nagata S, Shigita K, Aoyama T, Fukumoto A, Mukai S. Effectiveness and safety of endoscopic radial incision and cutting for severe benign anastomotic stenosis after surgery for colorectal carcinoma: a three-case series. Endosc Int Open. 2018;6:E335-E339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Harada K, Kawano S, Hiraoka S, Kawahara Y, Kondo Y, Okada H. Endoscopic radial incision and cutting method for refractory stricture of a rectal anastomosis after surgery. Endoscopy. 2015;47 Suppl 1:E552-E553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Belvedere B, Frattaroli S, Carbone A, Viceconte G. Anastomotic strictures in colorectal surgery: treatment with endoscopic balloon dilation. G Chir. 2012;33:243-245. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Garcea G, Sutton CD, Lloyd TD, Jameson J, Scott A, Kelly MJ. Management of benign rectal strictures: a review of present therapeutic procedures. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:1451-1460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Suchan KL, Muldner A, Manegold BC. Endoscopic treatment of postoperative colorectal anastomotic strictures. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1110-1113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Jain D, Sandhu N, Singhal S. Endoscopic electrocautery incision therapy for benign lower gastrointestinal tract anastomotic strictures. Ann Gastroenterol. 2017;30:473-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Muto M, Ezoe Y, Yano T, Aoyama I, Yoda Y, Minashi K, Morita S, Horimatsu T, Miyamoto S, Ohtsu A, Chiba T. Usefulness of endoscopic radial incision and cutting method for refractory esophagogastric anastomotic stricture (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:965-972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Araujo SE, Costa AF. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic balloon dilation of benign anastomotic strictures after oncologic anterior rectal resection: report on 24 cases. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2008;18:565-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Nepal P, Mori S, Kita Y, Tanabe K, Baba K, Uchikado Y, Kurahara H, Arigami T, Sakoda M, Maemura K, Natsugoe S. Radial incision and cutting method using a transanal approach for treatment of anastomotic strictures following rectal cancer surgery: a case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2019;17:48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |