Published online Aug 27, 2019. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v11.i8.348

Peer-review started: June 19, 2019

First decision: August 2, 2019

Revised: August 9, 2019

Accepted: August 13, 2019

Article in press: August 13, 2019

Published online: August 27, 2019

Processing time: 75 Days and 3.6 Hours

Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver (SFTL) is a rare occurrence with a low number of cases reported in literature. SFTL is usually benign but, 10%-20% cases are reported to be malignant with a tendency to metastasize. The majority of malignant SFTL cases are associated with a paraneoplastic hypoglycaemia defined as Doege-Potter syndrome. Surgery is the best therapeutic treatment, however, long- life follow-up is recommended.

A 74-year-old man, was admitted to the emergency department after a syncopal episode with detection of hypoglycaemia resistant to medical treatment. The computed tomography revealed a solid mass measuring 15 cm of the left liver. An open left hepatectomy was performed with complete resection of tumor. Histopathological analyses confirmed a malignant SFTL.

Large series with long-term follow-up have not been published neither have clinical trials been undertaken. Consequently, the methodical long-term follow-up of surgically treated SFTLs is strongly recommended.

Core tip: Solitary fibrous tumors (SFTs) are rare mesenchymal tumors first described in 1931 by Klemperer and Rabin. Usually, SFTs are benign, but 10%-20% of them are reported to be malignant with a tendency to metastasize. At present, 22 cases of liver malignant SFTs, including our patient, have been reported in literature. Some cases are associated with a paraneoplastic hypoglycaemia definied as Doege-Potter syndrome. Surgery is the best therapeutic modality and prolongs life, but also improves the clinical characteristics associated with Doege-Potter syndrome if present. Longlife follow-up is recommended.

- Citation: Delvecchio A, Duda L, Conticchio M, Fiore F, Lafranceschina S, Riccelli U, Cristofano A, Pascazio B, Colagrande A, Resta L, Memeo R. Doege-Potter syndrome by malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the liver: A case report and review of literature. World J Gastrointest Surg 2019; 11(8): 348-357

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v11/i8/348.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v11.i8.348

Solitary fibrous tumors (SFTs) are rare mesenchymal tumors first described in 1931 by Klemperer and Rabin[1]. Originally the are usually found in pleura but they have also been reported in other serous cavities such as pericardium and peritoneum. Such tumours have also been described in other unusual organs such as the liver, orbit, retroperitoneum, maxillary sinus, pancreas, upper respiratory tract, lung, soft tissues, kidneys, thyroid gland, meninges, and prostatic gland[2,3].

SFTs of the liver (SFTLs) are some of the most uncommon SFT, with only approximately 84 reported cases in the English literature[1]. SFTs are usually benign, but 10%-20% cases are reported to be malignant with a tendency to metastasize[2]. Histologically, they are characterized by proliferation of spindle cells, and immunohistochemically are positive for CD34 and BCL2 and bland for CD99[4].

Clinico-radiological features are not specific, therefore the diagnosis can be made only on the basis of histopathological data[2]. Some cases of malignant SFTs are associated with a paraneoplastic hypoglycaemia defined as Doege-Potter syndrome, described in pleural and extrapleural tumors[5].

Surgery is considered the best therapeutic modality, with outcomes dependent on resectability. Resection prolongs life, but also improves the clinical characteristics associated with Doege-Potter syndrome if present[6]. Longlife follow-up is recommended. We reported a new case of malignant SFTL treated at our Institute and reviewed 22 cases of this rare tumor present in English scientific literature.

A 74 years old man, was admitted to the emergency department for syncopal episode, with detection of hypoglycaemia resistant to medical treatment.

His past medical history included hypertension, benign prostatic hypertrophy and glaucoma.

Physical examination revealed a morbidly obese (body mass index = 35), painless hepatomegaly without weight loss.

Investigations reported a marked hypoglycaemia, with capillary blood glucose measurements ranged from 30 to 70 mg/dL treated with continuous glucose infusion and a rich carbohydrate diet.

Laboratory tests revealed low levels of insulin: 0.3 mcrU/mL (range 5-25 mcrU/mL), low levels of C-peptide: < 0.10 ng/dL (range 0.9-4 ng/dL), low levels of GH: <0.02 ng/dL (range 0.02-1.23 ng/dL), normal level of cortisol: 8.9 mcg/dL (range 3.7-19.4 mcg/dL), normal level of insulin-like growth factor I (IGFI): 84 ng/mL (range 20-300 ng/mL) and normal level of insulin-like growth factor II (IGFII): 575.70 ng/mL (range 373-1000 ng/mL) in the patient’s serum. The IGFII/IGFI ratios was 7:1. Liver functions, viral panel, tumor markers (alpha-fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen and cancer antigen 19-9) were within the normal limits.

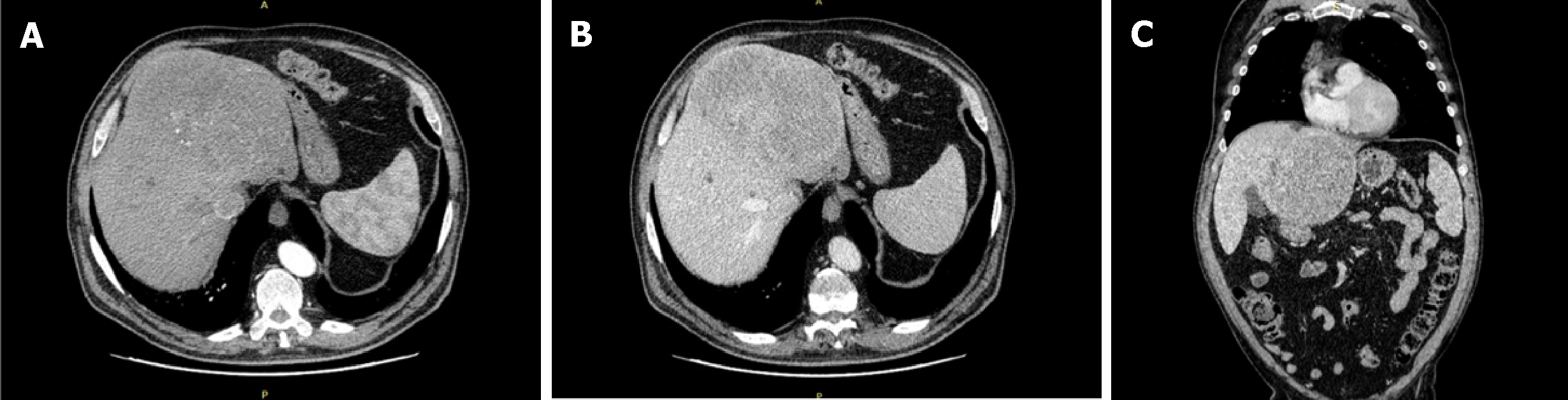

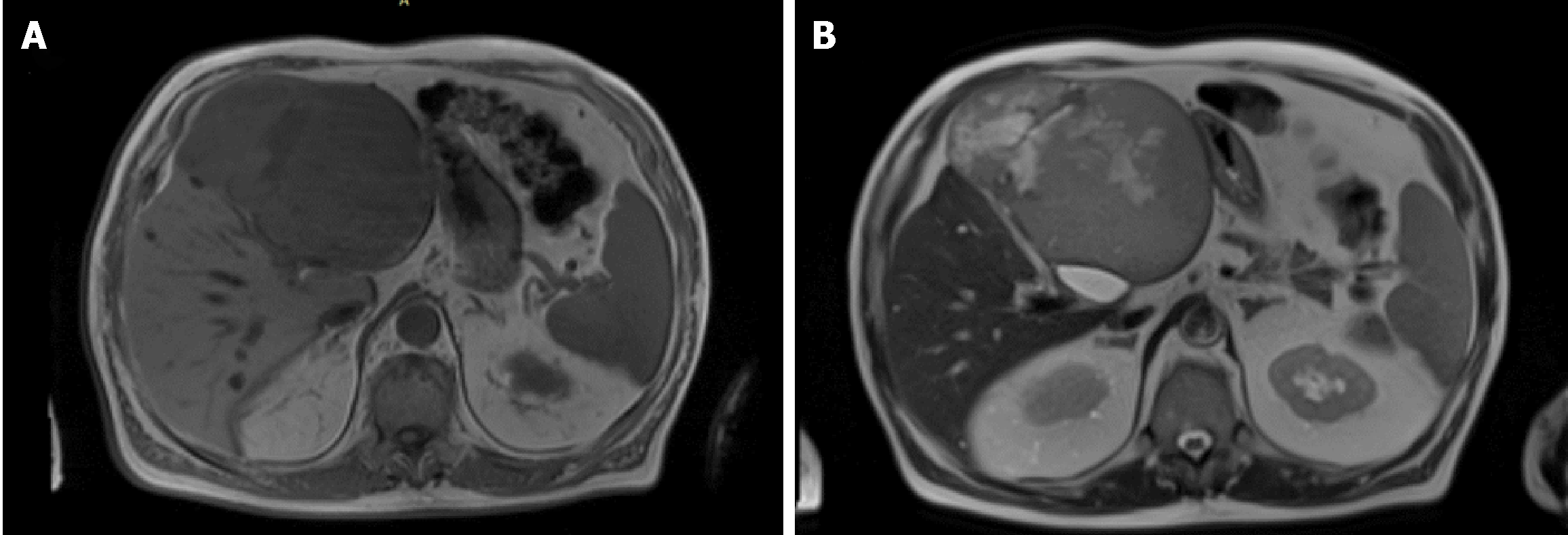

A total body computed tomography (CT) was performed and revealed a solid mass measuring 15 cm of the left liver. The intravenous contrast demonstrate an inhomogeneous enhancement for necrosis within the tumour as well as a thick capsule that enhances during the portal phase (Figure 1). Radiological findings on abdominal magnetic resonance (MR) were similar to ones described for abdominal TC with evidence of a voluminous liver mass measuring 15 cm × 13 cm (Figure 2). There was no evidence of metastatic disease

Doege-Potter syndrome by malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the liver.

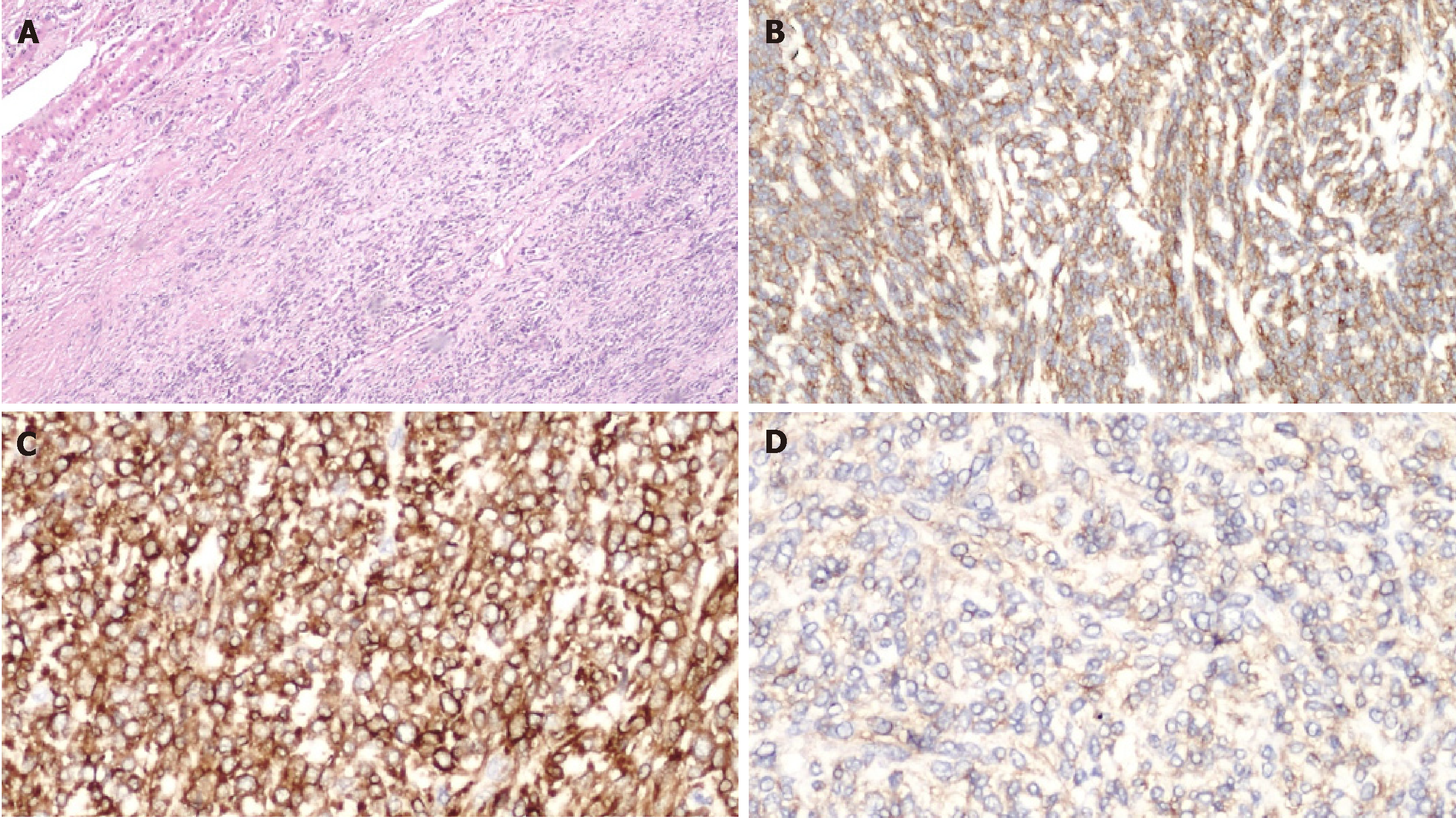

A left hepatectomy was performed with complete resection of tumor and free margin were obtained. Intraoperative ultrasound (IOUS) revealed a left liver tumor mass of 15 cm. There were no sign of contiguous organ invasion or other hepatic lesion. The parenchymal transection was performed with an ultrasonic dissector and bipolar sealers. On frozen section SFT present well circumscribed but unencapsulated border with infiltrative pattern and central necrosis (Figure 3).

Immediately after surgery glucose serum levels returned to a physiologic daily profile. The patient was discharged on postoperative day four without complications. Histopathological analyses confirmed a malignant SFTL; microscopically, the tumours tissue showed a proliferation of spindle cells with infiltrative pattern of hepatic parenchyma, immunochemistry show strong positivity for CD34 and BCL2 and bland for CD99 and negative for ActinaML, Desmine, Cd117, CK pool, S100. The mitotic activity index Ki67 was 35% (Figure 4). Adjuvant protocol of chemiotherapy with Epirubicin and Ifosfamide was started. The patient was subjected to a strictly follow-up every 3-4 mo in the first 2-3 years after surgey, twice each year up to the 5th year and then once a year after the 5th year. Five months after surgery there were no signs of local recurrence or distant metastases.

An English literature search regarding “Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver”, “Malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the liver”, “Mesenchymal tumor”, “Hepatic tumor”, “Doege-Potter syndrome” was conducted using the common search engines and the relevant articles were reviewed and analysed. The reference list of each article was inspected searching for other articles reporting SFTL that were analysed and included in this report.

We selected all cases of malignant SFTL reported in the literature considering a total number of 19 articles and we excluded cases of benign SFTL or extrahepatic localization. At present, 22 cases of malignant SFTL, including including the patient described in this article, have been reported in literature (Table 1). All represent case reports except for one case series with three case series described by Maccio et al[7].

| No | Author (yr) | Age/Sex | Presenta-tion | Lobe | Size | Treatment | Histopatho-logy | Tumor-markers | IHC | Follow up |

| 1 | Fuksbrumera et al[28] (2000) | 71/F | NA | R | 14 × 17 | Resection (UM) | Increased nuclear atypia, mitoses 8/10 HPF | NA | CD34+, Bcl2+, V+ | NA |

| 2 | Yilmaz et al[18] (2000) | 25/F | Weakness,fatigue, anorexia, vomiting and progressive jaundice | L + R | 32 × 30 | Resection (UM) | Cellularity ranged from 20%-60%, necrosis, hypervascularity | NAD | V+ | Bone metastasis 1 mo postsurgery managed with 6 mo of chemo (cyclophosphamide, adriamycin) |

| 3 | Terkivatan et al[29] (2006) | 74/M | Gastric fullness, postprandial nausea, and weight loss | L | 24 × 21 × 15 | Resection (FM) | A few highly cellular areas mitoses 10 - 13/10 HPF | NAD | CD34+, CD99+, Bcl2+, V+ | 12 mo no signs of local recurrence or distant metastases |

| 4 | Chan et al[16] (2007) | 70/M | Hypoglycaemia, progressive jaundice | R | 27 × 24 × 12 | Failed TACE 6 wk preoperatively followed by successful resection (UM) | Mildly atypical spindle cells, highly cellular, plemorphia, necrosis, mitoses > 20 HPF | CA-125: 145 U/mL (normal< 35 U/mL) | CD34+, CD99+, bcl2+, V+ | bilateral lung metastasis and bi-lobar recurrence at 9 mo |

| 5 | Brochard et al[30] (2010) | 54/M | Abdominal pain, weight loss | R | 17 | Resection (FM) | Moderately cellular, polymorphic cells, mitoses < 5/10 HPF | NAD | CD34+, V+, desmin+, actin+ | Patient died 1 mo after for Local recurrence 6 yr postsurgery, cranial base metastasis, Retroperitoneal and iliac bone metastasis |

| 6 | Fama et al[21] (2008) | 68/M | Hypoglycaemic coma | R | 15 | Resection (FM) | Hypercellular, moderately atypical nuclei, mitoses 20/10 HPF | NAD | CD34+, Bcl2+ | 25 mo no signs of local recurrence or distant metastases |

| 7 | Peng et al[17] (2011) | 24/F | Abdominal discomfort and distention | R | 30 × 17 × 15 | TACE few days prior to resection (FM) | Highly cellular, pleomorphic, necrosis, mitoses > 10/HPF | CA-125 augmented | CD34+, bcl2+, V+ | Patient died 16 mo after initial surgery for skull base metastases, Vertebral metastasis |

| 8 | Belga et al[31] (2012) | 66/F | Increase in abdominal girth | R | 14 | Resection (UM) | Mitoses > 4/10 HPF, necrosis, mild nuclear atypia | NAD | CD34+ | 30 mo no signs of local recurrence or distant metastases |

| 9 | Jakob et al[32] (2013) | 62/F | Upper abdominal pain, weight loss | L | NA | Resection (UM) | High cellularity, cytological atypia, necrosis, mitoses 6/10 HPF | NAD | CD34+, CD99+, bcl2+ | NA |

| 10 | Vythianathan and Yong[33] (2013) | 78/M | Epigastric pain | L | 17 × 13 | Resection (UM) | Cellular pleomorphism, necrosis, mitoses > 4/10 HPF | NA | CD34+, CD99+, bcl2+, V+ | NA |

| 11 | Song et al[34] (2014) | 49/M | Abdominal pain | L+R | 7.6 × 5 × 4.8 | Resection (UM) | NAD | NA | CD34+, bcl2+, V+ | NA |

| 12 | Du et al[4] (2015) | 55/F | Hypoglycaemia, weight loss | L | 15.3 × 15.5 × 15.4 | Resection (UM) | NA | NAD | CD34+, bcl-2+ | Local recurrence 5 yr postsurgery, resected |

| 13 | Feng et al[8] (2015) | 52/F | NA | R | 12 | Resection (UM) | Haemorrhage, necrosis | NAD | CD34+ | Local recurrence 2 yr postsurgery on L lobe managed with PEI. New lesion 6 mo after PEI |

| 14 | Silvanto et al[35] (2015) | 65/M | Incidental finding | L | 18 | Resection (FM) | Myxoid changes, infarction, necrosis mitoses 5-7/10 HPF | NAD | CD34+, CD99+, Bcl2+ | 16 mo no signs of local recurrence or distant metastases |

| 15 | Maccio et al[26] (2015) | 74/F | Right abdominal pain, distension | R | 24 × 16 | Resection (UM) | Nuclear pleomorphism, cytological atypia, necrosis, haemorrhage, mitoses 9/10 HPF | NA | CD34+, Bcl2+, V+, STAT6+ | Lung, omentum, mesentery and abdominal wall metastasis at 9 mo. Patient died 4 mo later |

| 16 | 80/F | Dyspnoea, cough, asthenia, abdominal pain | R | 19 × 15 | Palliative Chemotherapy | Highly cellular, pleomorphism, necrosis, haemorrhage, mitoses 7/10 HPF | NA | CD34+, Bcl-2+, V+, STAT6+ | R lung metastasis. Patient died 5 mo later | |

| 17 | 65/M | Abdominal discomfort, vomiting and pain | R | 3 × 2 | Chemotherapy | Cytological atypia, necrosis, mitoses > 6/10 HPF | NA | CD34+, Bcl2+, V+, STAT6+ | Bilateral lung metastasis. Patient died 5 mo later | |

| 18 | Nelson et al[1] (2016) | 61/M | Diarrhoea | R | 15 × 11.5 × 7.5 | Resection (FM) | Myxoid changes, mitoses > 9/10 HPF | NAD | CD34+, CD99+, Bcl2+ | Extensive local recurrence and pleural metastases. Patient died 6 yr post-surgery |

| 19 | Esteves et al[7] (2018) | 68/F | Incidental finding | R | 13.3 × 11.6 × 13.5 | Resection (FM) | Focal high-grade cytologic atypia, mitoses 25-27/10 HPF | NAD | CD34+, STAT6+ | 20-mo follow-up multiple bilateral pulmonary |

| 20 | De Los Santos-Aguilar et al[36] (2019) | 61/M | hypoglycemia disorientation, incoherent speech | R | 16 × 13 × 11 | Right portal embolization. Six weeks after resection (FM) | High proliferation rate of 8/10 HPF Ki-67 15% | NAD | CD34+, Bcl2+, CD99+ | No evidence of metastases |

| 21 | Yugawa et al[10] (2019) | 49/F | Malaise abdominal bloating | R | 14 | Resection (FM) | Foci of hemorrhage and necrosis Mitosis 1/20 HPF) | NAD | STAT6+ V+ | 12 mo no signs of local recurrence or distant metastases |

| 22 | Present case | 74/M | Hypoglycemia | L | 15 × 13 | Resection (FM) | Moderately cellular, pleomorphism, necrosis, mitoses 4/10 HPF Ki-67 35% | CD34+, Bcl2+, CD99+ | At the moment, 2 mo no signs of local recurrence or distant metastases |

Malignant SFTL occurs with almost equal distribution between males (11, 50%) and female (11, 50%). It occurs more in the right lobe (14 cases, 64%) than the left one (6 cases, 27%). There was also two cases (9%) of bilateral localization. The average age of these patients was 61.1 years (range 24-80).

The clinical presentation was non-specific, ranging from weakness, fatigue, anorexia, vomiting, progressive jaundice, disorientation, incoherent speech, malaise abdominal bloating, abdominal discomfort, dyspnoea, abdominal pain, abdominal distension, weight loss. The syndrome of hypoglycaemia was seen in about 23%, five of 22 cases reported. There was no specific laboratory tests or tumor markers for malignant SFTL.

In our review 17 patients (77%) were treated with resection: 9 with unknown tumor margins and 8 with free tumor margins. One patient was treated with failed trans-arterial chemo embolization (TACE) and successful resection with unknown margins. Another case was subjected to TACE followed by resection. Two patient underwent to chemotherapy. One patient was treated with a right portal embolization and successful resection with free tumor margins.

Follow up was not available for 4 cases, no sign of local recurrence or distant metastasis in 7 cases (32%) with an average follow up duration of 17 mo. Local recurrence or distant metastasis were found in 11 patients (50%) with a averge time post-surgery of 27 mo.

SFT first described in the year 1931, is a rare neoplasm commonly located in the pleura and this tumor accounts for less than 2% of all soft tissue tumors[8,9]. SFT is considered a benign tumor with the potential for malignant transformation but the classification of this neoplasm is not yet clear in literature[4,10]. SFT of the liver (SFTL) is particularly rare, therefore the classification as a benign or malignant tumor remains controversial[11]. SFTL was reported for the first time in an article published in 1959 by Nevius and Friedman where three SFT in different localizations were described, one of them was a liver SFT and was clinically presented with hypoglycaemia[12].

England et al[13] established the criteria for malignant SFT: Mitotic changes (> 4/10 HPFs), tumor necrosis and hemorrhage, nuclear pleomorphism, and metastasis were the major criteria; large tumor size (> 10 cm) and cellular atypia were the minor criteria.

Wilky et al[14] classified the SFT into “benign” with no atypical features and no England’s criteria, “borderline” with 1 or more England’s criteria but final classification as benign, and “malignant.” This report described that “borderline” SFT with any of England’s criteria had been related to high risk of recurrence.

In the 2013 WHO classification of tumors of soft tissue and bone, extrapleural SFT was considered a fibroblastic/myofibroblastic neoplasm with uncertain biological behaviour, rarely metastasizing[15]. In the latest modified WHO classification of soft tissue tumors, SFT was divided into two categories: Solitary fibrous tumor and malignant solitary fibrous tumor[16]. However, according to the updated WHO classification of the digestive-system disorders, SFT is considered a benign tumor with the potential for malignant transformation, the benign or malignant classification of this neoplasm has not yet reached a consensus[4,10].

Chen et al[1] reported that 16 of 84 SFTL were malignant, which was similar to the intrapleural SFT recurrence rate of 20%-67% among malignant tumors. Histologically the tumour exhibits a hypercellular spindle-cell proliferation creating storiform arrays with hemangiopericytomatous branching vessels and a moderate to marked atypia. There was parenchymal invasion and no vascular infiltration. High mitotic count (12 per HPF) was observed.

Immunochemistry show strong positivity for CD34 and BCL2 and bland for CD99 and negative for EPAR1 Cytokeratin, CD117, DOG1, ActinaML and Desmine. The mitotic activity index Ki67 was in range from 15% to 20%. SFTL tendencies to be well circumscribed and encapsulated or partially encapsulated, with infiltrative pattern and central necrosis and a growth of > 20 cm in diameter. Malignant SFTL is rare with only 22 cases reported in literature including the present case (Table 1). Literature reported that SFTL usually occurs in female patient over 45 years of age, with no apparent predisposition, in either the right or left sides of the liver[1].

Clinical presentation of these tumors is usually non-specific and the majority of the patients are initially asymptomatic, with an incidental diagnosis, until the tumor attains a large size and presents with symptoms due to mass effect with compression of adjacent organs[2]. Clinical symptoms reported are non-specific, such as weight loss, right upper quadrant pain, fatigue, abdominal distension, gastric plenitude associated to nausea and postprandial vomit depending by tumor size[3]. The clinical presentation of malignant SFTL did not differ notably from the clinical presentation of benign SFTL, have described cases with intractable hypoglycemia[17], unspecific symptoms including abdominal pain and weight loss or muscular and neurological symptoms due to metastatic disease[18,19]. Hypoglycemia (diaphoresis, tremor, anxiety, and lost consciousness) accompanying SFT is the predominant symptom of Doege-Potter syndrome, generally is associated with malignant SFT and was first described in 1930 in a case report by Doege[20-22].

Our patient was conducted at our institution for a left liver mass and severe hypoglycaemia. The physical examination was not specific, in the literature the rare possibility of palpating a solid mass located above the right emmiabdomen and epigastrium is reported. In other cases, the abdominal circumference increases and peripheral edema develops[23]. We asked for an endocrinologist consultation, for the persistent hypoglycaemia, that rejected the insulinoma hypothesis for the low levels of insulin and C-peptide and confirmed that the hypoglycaemia was caused by the presence of insulin-like factors produced by the neoplasm. Although the serum values of IGF-I and IGF-II were normal, the IGFII/IGFI ratios was high.

The IGFII/IGFI ratio is considered a marker of high IGF-II concentration; a ratio of 3: 1 is normal, and in most IGFII-producing tumors the ratio is 10:1. In our case, the spontaneous symptomatic hypoinsulinemic hypoglycaemia, increased IGII/IGFI ratio (7:1), suppression of GH, and the associated clinical features made IGF-II-mediated hypoglycaemia the most likely aetiology.

The typical mechanism involves ectopic tumor production of insulin or other similar hormone such us insulin-like growth factor IGF-II, called “big IGF-II,” which has insulin-like effects on the body, stimulating glucose uptake by insulin-sensitive tissues and the tumor itself[3]. IGF-II expression is high during fetal life and is relatively independent from growth hormone. That is the reason why its expression is coherent with the development of this primitive mesenchymal tumor[3]. It has been observed that the hypoglycemia intractable is associated with malignant transformation, suggesting that this phenomena is due to increased biologic activity in malignant SFTL cells[17]. No specific laboratory parameters findings for SFTL are currently available. Laboratory tests such as blood count or C reactive protein, serum tumor markers such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), alpha-fetal-protein (AFP), and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) are normal[3,23,24].

Radiological studies are unspecific and cannot be definitively distinguish between malignant or benign hepatic tumors. Ultrasound identifies the presence of a solid well-defined ovoid heterogeneous mass, in some cases homogenous and hyperechoic compared with the normal hepatic parenchyma. Computed tomography with intravenous contrast demonstrate a well-defined encapsulated hypervascular tumor and progressive heterogeneous enhancement, it is possible to identify cystic/necrotic areas within the mass. Radiological findings on abdominal MR are similar to the ones described for abdominal CT. The clinical utility of positron emission tomography (PET) in SFTL has not been established[2,9,25].

The majority of SFTL display benign clinical features, even if it should always be considered potentially malignant. R0 surgical resection remains the only therapeutic option and it has been proved to the solution to normalize glycaemia. In these patients lifelong follow-up is recommended for the high risk of recurrence[3,17,26]. Considering the literature, benefit of radio and chemotherapy is unknown, as well as prognosis due to the little experience and understanding of the biological nature of the disease[27].

Large series with long-term follow-up have not been published neither clinical trials have been undertaken. For all of these reasons, the methodical long-term follow-up of surgically treated SFTLs is strongly recommended.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: de Bree E, Isik A, Rubbini M S-Editor: Ma RY L-Editor: A E-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Chen N, Slater K. Solitary fibrous tumour of the liver-report on metastasis and local recurrence of a malignant case and review of literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2017;15:27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Shinde RS, Gupta A, Goel M, Patkar S. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver - An unusual entity: A case report and review of literature. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2018;22:156-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Beltrán MA. Solitary Fibrous Tumor of the Liver: a Review of the Current Knowledge and Report of a New Case. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2015;46:333-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Feng LH, Dong H, Zhu YY, Cong WM. An update on primary hepatic solitary fibrous tumor: An examination of the clinical and pathological features of four case studies and a literature review. Pathol Res Pract. 2015;211:911-917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Du EH, Walshe TM, Buckley AR. Recurring rare liver tumor presenting with hypoglycemia. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:e11-e13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zafar H, Takimoto CH, Weiss G. Doege-Potter syndrome: hypoglycemia associated with malignant solitary fibrous tumor. Med Oncol. 2003;20:403-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Maccio L, Bonetti LR, Siopis E, Palmiere C. Malignant metastasizing solitary fibrous tumors of the liver: a report of three cases. Pol J Pathol. 2015;66:72-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Dey B, Gochhait D, Kaushal G, Barwad A, Pottakkat B. Solitary Fibrous Tumor of the Liver: A Rare Tumor in a Rarer Location. Rare Tumors. 2016;8:6403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Esteves C, Maia T, Lopes JM, Pimenta M. Malignant Solitary Fibrous Tumor of the Liver: AIRP Best Cases in Radiologic-Pathologic Correlation. Radiographics. 2017;37:2018-2025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bosman FT. WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system-NLM Catalog-NCBI. In: WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system 2010; . |

| 11. | Yugawa K, Yoshizumi T, Mano Y, Kurihara T, Yoshiya S, Takeishi K, Itoh S, Harada N, Ikegami T, Soejima Y, Kohashi K, Oda Y, Mori M. Solitary fibrous tumor in the liver: case report and literature review. Surg Case Rep. 2019;5:68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | NEVIUS DB, FRIEDMAN NB. Mesotheliomas and extraovarin thecomas with hypoglycemic and nephrotic syndromes. Cancer. 1959;12:1263-1269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | England DM, Hochholzer L, McCarthy MJ. Localized benign and malignant fibrous tumors of the pleura. A clinicopathologic review of 223 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:640-658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 953] [Cited by in RCA: 845] [Article Influence: 23.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wilky BA, Montgomery EA, Guzzetta AA, Ahuja N, Meyer CF. Extrathoracic location and "borderline" histology are associated with recurrence of solitary fibrous tumors after surgical resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:4080-4089. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Fisher C. Atlas of Soft Tissue Tumor Pathology. New York: Springer 2013; . [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Jo VY, Fletcher CD. WHO classification of soft tissue tumours: an update based on the 2013 (4th) edition. Pathology. 2014;46:95-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 505] [Cited by in RCA: 669] [Article Influence: 60.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chan G, Horton PJ, Thyssen S, Lamarche M, Nahal A, Hill DJ, Marliss EB, Metrakos P. Malignant transformation of a solitary fibrous tumor of the liver and intractable hypoglycemia. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14:595-599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Peng L, Liu Y, Ai Y, Liu Z, He Y, Liu Q. Skull base metastases from a malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the liver. A case report and literature review. Diagn Pathol. 2011;6:127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yilmaz S, Kirimlioglu V, Ertas E, Hilmioglu F, Yildirim B, Katz D, Mizrak B. Giant solitary fibrous tumor of the liver with metastasis to the skeletal system successfully treated with trisegmentectomy. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:168-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chamberlain MH, Taggart DP. Solitary fibrous tumor associated with hypoglycemia: an example of the Doege-Potter syndrome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;119:185-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Heuer GJ. Intrathoracic tumors: experiences with eight cases of tumor of the thoracic wall pleura and mediastinum. Ann Surg. 1924;79:670-686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Famà F, Le Bouc Y, Barrande G, Villeneuve A, Berry MG, Pidoto RR, Saint Marc O. Solitary fibrous tumour of the liver with IGF-II-related hypoglycaemia. A case report. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2008;393:611-616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ji Y, Fan J, Xu Y, Zhou J, Zeng HY, Tan YS. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2006;5:151-153. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Makino Y, Miyazaki M, Shigekawa M, Ezaki H, Sakamori R, Yakushijin T, Ohkawa K, Kato M, Akasaka T, Shinzaki S, Nishida T, Miyake Y, Hama N, Nagano H, Honma K, Morii E, Wakasa K, Hikita H, Tatsumi T, Iijima H, Hiramatsu N, Tsujii M, Takehara T. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver from development to resection. Intern Med. 2015;54:765-770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Soussan M, Felden A, Cyrta J, Morère JF, Douard R, Wind P. Case 198: solitary fibrous tumor of the liver. Radiology. 2013;269:304-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Weitz J, Klimstra DS, Cymes K, Jarnagin WR, D'Angelica M, La Quaglia MP, Fong Y, Brennan MF, Blumgart LH, Dematteo RP. Management of primary liver sarcomas. Cancer. 2007;109:1391-1396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Novais P, Robles-Medranda C, Pannain VL, Barbosa D, Biccas B, Fogaça H. Solitary fibrous liver tumor: is surgical approach the best option? J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2010;19:81-84. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Fuksbrumer MS, Klimstra D, Panicek DM. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver: imaging findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175:1683-1687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Terkivatan T, Kliffen M, de Wilt JH, van Geel AN, Eggermont AM, Verhoef C. Giant solitary fibrous tumour of the liver. World J Surg Oncol. 2006;4:81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Brochard C, Michalak S, Aubé C, Singeorzan C, Fournier HD, Laccourreye L, Calès P, Boursier J. A not so solitary fibrous tumor of the liver. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2010;34:716-720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Belga S, Ferreira S, Lemos MM. A rare tumor of the liver with a sudden presentation. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:e14-e15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Jakob M, Schneider M, Hoeller I, Laffer U, Kaderli R. Malignant solitary fibrous tumor involving the liver. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:3354-3357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Vythianathan M, Yong J. A rare primary malignant solitary fibrous tumour of the liver. Pathology. 2013;. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Song L, Zhang W, Zhang Y. (18)F-FDG PET/CT imaging of malignant hepatic solitary fibrous tumor. Clin Nucl Med. 2014;39:662-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Silvanto A, Karanjia ND, Bagwan IN. Primary hepatic solitary fibrous tumor with histologically benign and malignant areas. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2015;14:665-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | De Los Santos-Aguilar RG, Chávez-Villa M, Contreras AG, García-Herrera JS, Gamboa-Domínguez A, Vargas-Sánchez J, Almeda-Valdes P, Reza-Albarrán AA, Iñiguez-Ariza NM. Successful Multimodal Treatment of an IGF2-Producing Solitary Fibrous Tumor With Acromegaloid Changes and Hypoglycemia. J Endocr Soc. 2019;3:537-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |