Published online Mar 27, 2019. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v11.i3.191

Peer-review started: February 11, 2019

First decision: February 26, 2019

Revised: March 14, 2019

Accepted: March 20, 2019

Article in press: March 20, 2019

Published online: March 27, 2019

Processing time: 52 Days and 12.1 Hours

Ganglioneuromas are mature, benign neurogenic tumors that arise from neural crest-derived cells. Given the rarity of these tumors and their often close proximity to major vessels, there is a paucity of reports in the literature of minimally invasive resections of ganglioneuromas near the celiac plexus. We report a case of laparoscopic resection of a retroperitoneal ganglioneuroma adhering to the portal vein and celiac axis.

A 27-year-old female was referred to our medical center with a symptomatic retroperitoneal mass. Using high quality preoperative imaging and biopsies, we confirmed the diagnosis of a 4 cm ganglioneuroma abutting the celiac axis, portal vein, and the caudate lobe of the liver. We elected for laparoscopic resection after careful preoperative planning and discussions with the patient. Laparoscopy enhanced visualization of the tumor and its relationships to surrounding vital structures for optimal dissection. Ultrasonic energy devices and adjusting liver retraction to allow for manipulation of the mass facilitated a safe and effective resection in a tight space. There were no operative complications and the patient was discharged home on postoperative day 1 with no residual symptoms upon follow-up. With sufficient experience in laparoscopic surgery and preoperative imaging and diagnostics, a minimally invasive approach for removing this celiac plexus ganglioneuroma was successful.

In carefully selected patients, laparoscopic ganglioneuroma resection is appropriate, reducing postoperative morbidity, hospital length of stay, and recovery time.

Core tip: Ganglioneuromas are rare, benign neurogenic tumors. Given their often close proximity to major vessels, minimally invasive resection can be challenging. We report a case of laparoscopic resection of a retroperitoneal ganglioneuroma adhering to the portal vein and celiac axis. Laparoscopy enhanced visualization of the tumor and its relationships to surrounding vital structures. Ultrasonic energy devices and adjusting liver retraction allowed for manipulation of the mass and safe dissection in a tight space. With sufficient experience in laparoscopic surgery, careful patient selection, and preoperative imaging and diagnostics, laparoscopic ganglioneuroma resection can reduce postoperative morbidity, hospital length of stay, and recovery time for the patient.

- Citation: Hemmati P, Ghanem O, Bingener J. Laparoscopic celiac plexus ganglioneuroma resection: A video case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 2019; 11(3): 191-197

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v11/i3/191.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v11.i3.191

Ganglioneuromas are mature, benign neurogenic tumors that arise from neural crest-derived cells. They are typically asymptomatic, nonfunctional neoplasms. Due to indolent growth, they are typically diagnosed incidentally on imaging or due to mass effect-related symptoms. Surgical resection of these tumors offers excellent prognosis, even if incomplete[1]. There is a paucity of reports in the literature of laparoscopic resection of ganglioneuromas near the celiac plexus and the portal vein. However, with appropriate preoperative workup, imaging, and patient selection, a minimally invasive approach for resection of these rare tumors can be safe and effective. As shown in the following case presentation, laparoscopic resection facilitated reduced hospital stay and recovery time.

A 27-year-old female with chronic symptoms of nausea, vomiting, bloating, diarrhea and epigastric pain that radiated into her back was referred to our clinic.

She experienced these symptoms for several years but they progressively worsened and became disabling until she could no longer work as a truck driver. Specifically, the symptoms were motion-associated and relieved when she was at rest. She denied fevers, fatigue, or unintentional weight loss.

She was otherwise healthy at the time of presentation. He past medical history included recurrent urinary tract infections and remote episodes of pyelonephritis. Her medications included ondansetron for nausea and a hormonal intrauterine device.

Family history was non-contributory.

All vital signs were within normal limits. The physical exam was only notable for epigastric abdominal tenderness with radiation posteriorly.

Her laboratory workup was completely normal (including levels of amylase, lipase, liver enzymes, and catecholamines).

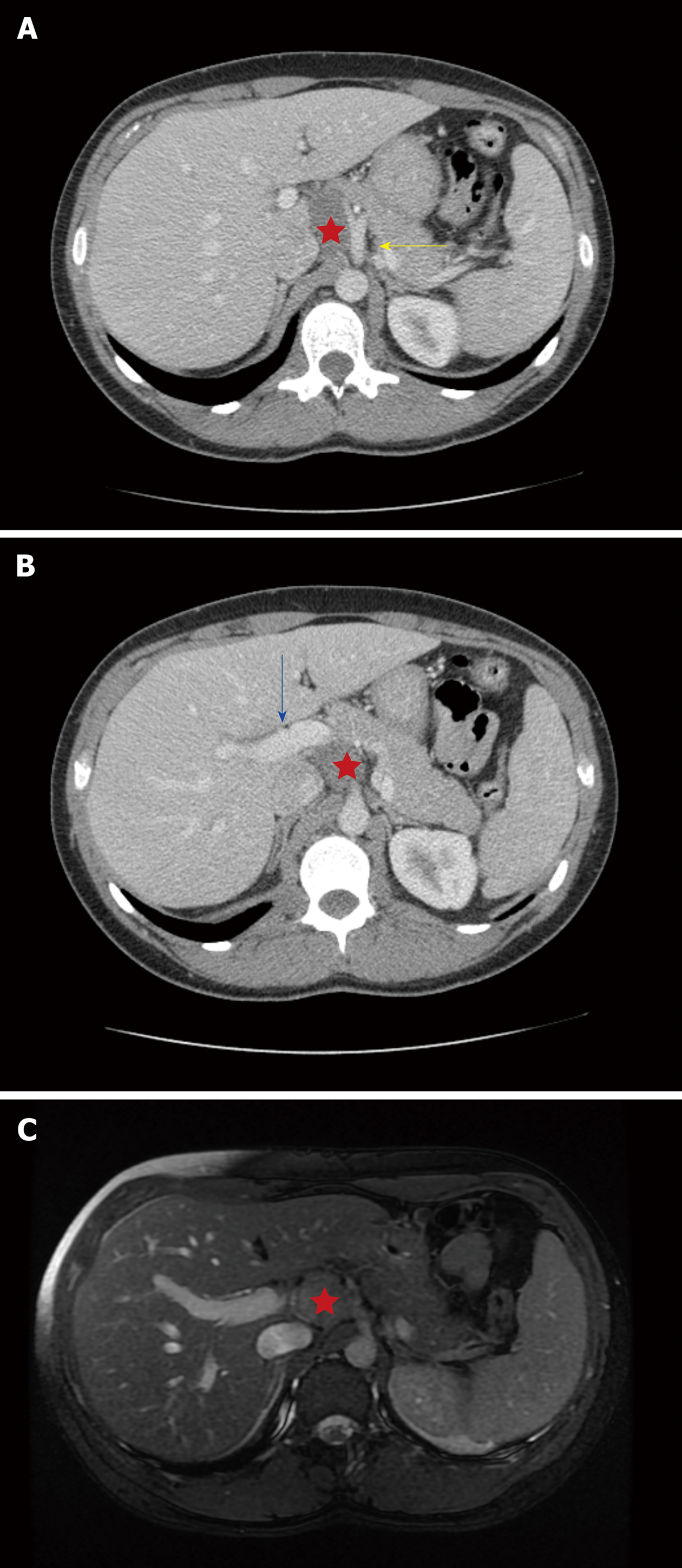

She underwent an abdominal ultrasound, which demonstrated a lobulated, hypoechoic mass (29 mm × 33 mm × 28 mm) in the retroperitoneum. A subsequent abdomen and pelvis computed tomography (CT) showed a benign-appearing, noninvasive hypodense mass (37 mm × 24 mm × 29 mm) abutting the portal vein, celiac axis, common hepatic artery, and the caudate lobe of the liver. A representative image from the CT (Figure 1A) shows the close proximity to these vital structures. However, there was no evidence of vascular encasement and fat planes were preserved. There was an inferomedial extension of the mass posterior and caudal to the portal vein (Figure 1B). Finally, an magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed the location and relationships of the mass (26 mm × 37 mm × 36 mm), also demonstrating no vascular encasement and an enhancing capsule (Figure 1C).

Differential diagnoses included retroperitoneal duplication cyst, primary neurogenic tumors (schwannoma, ganglioneuroma, or ganglioneuroblastoma), primary mesenchymal tumors, metastatic disease, or an enlarged lymph node. An endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration revealed mature, binucleate ganglion cells and other scant neural tissue. The cells were positive for neural markers (S-100 and synaptophysin) and negative for C-Kit, desmin, and DOG-1.

Given these findings, the mass was a benign neural-crest cell-derived lesion consistent with a ganglioneuroma.

It was unclear if the mass was truly causing her symptoms. However, a celiac plexus block (endoscopic ultrasound-guided transgastric injection of 0.25% bupivicaine and triamcinolone) immediately improved her disabling symptoms, allowing her to return to work. This improvement was transient, however, and it was determined that she would benefit from operative excision of this mass. Based on discussions with the patient and preoperative imaging, it was determined that a laparoscopic approach would be feasible.

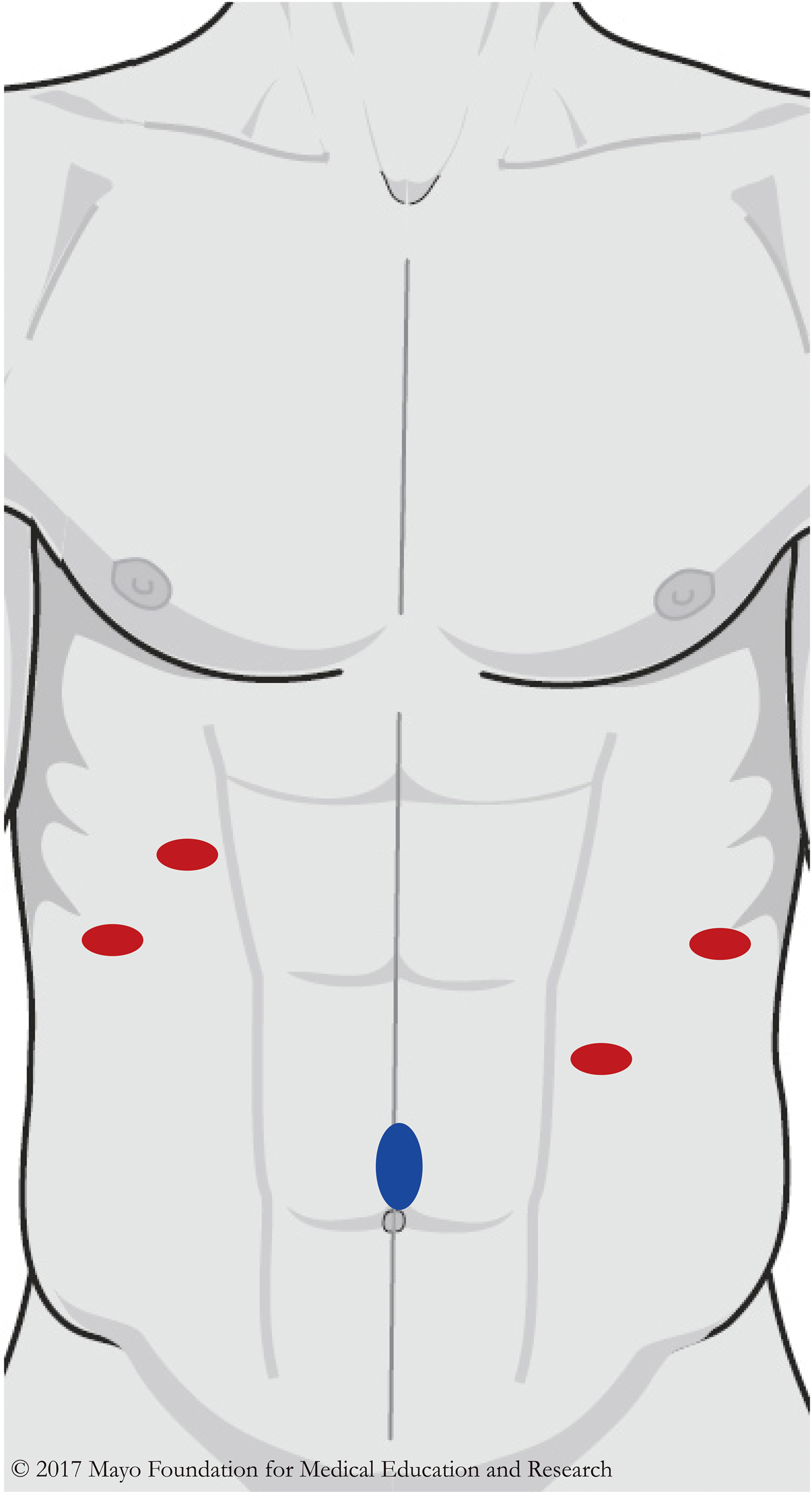

We gained access into the abdomen with a supraumbilical Hasson trocar and placed 4 additional 5 mm trocars under direct vision (Figure 2). We placed the liver retractor in the right lateral subcostal port and retracted the liver superiorly to expose the mass. An ultrasonic energy device, hook cautery, and blunt dissection were used to divide soft tissue attachments to adjacent structures.

The mass was quite adherent to its surroundings, making blunt dissection difficult. This resulted in oozing in the operative field, which was effectively controlled with the ultrasonic energy device. The medial dissection was the most critical due to the proximity to the portal vein. Due to the extension of the ganglioneuroma posterior and caudal to the portal vein, we had to alter tension on the hepatoduodenal ligament to continue dissection in the retroperitoneum. This was accomplished with changing liver retraction and we were able to completely remove the mass.

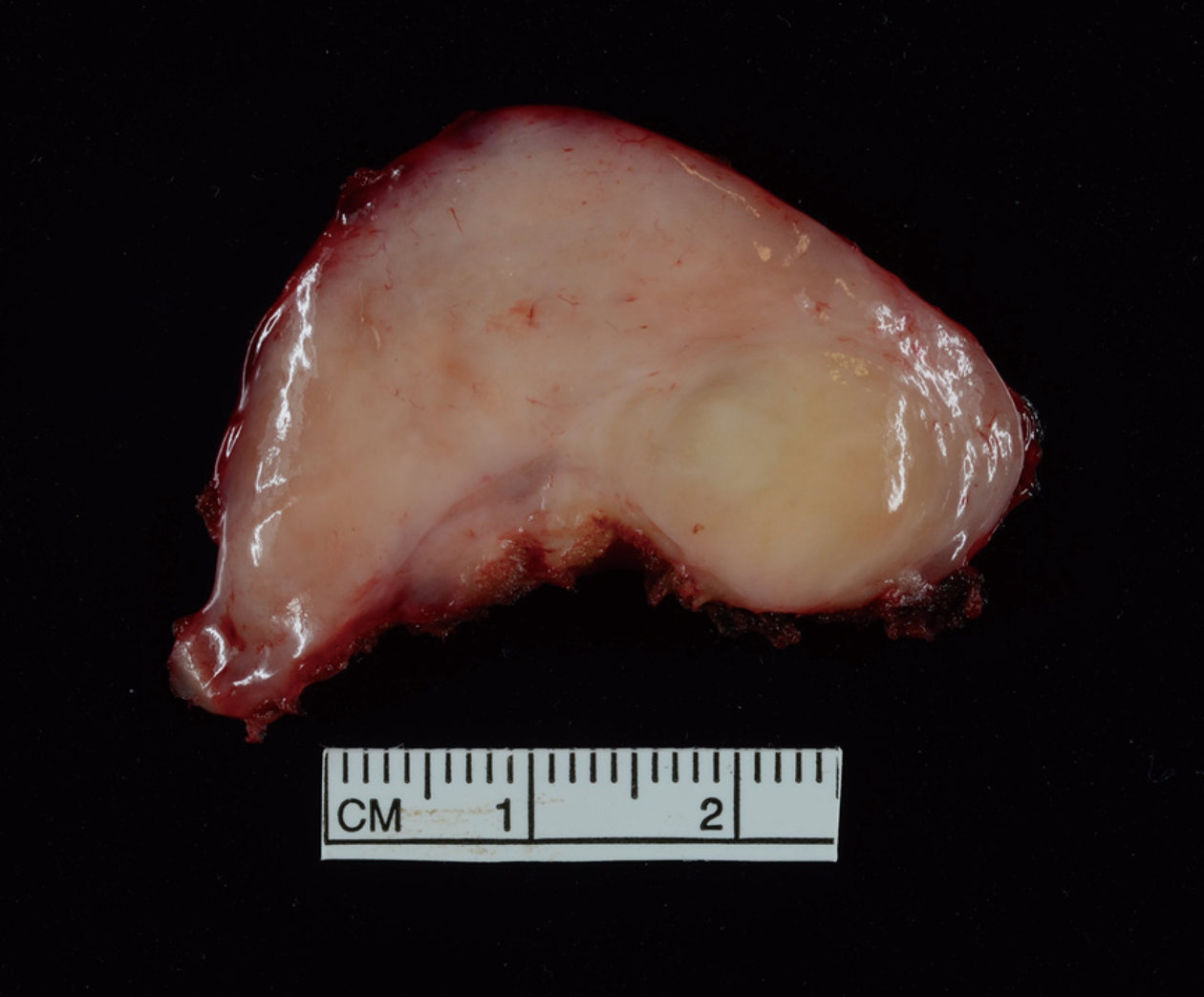

There were no intraoperative complications. She had an uneventful recovery on the general surgical floor and was discharged on postoperative day 1. Upon follow up, she continued to do well and her symptoms had significantly improved. The final pathology was concordant and demonstrated a 43 mm × 25 mm × 24 mm lobulated, circumscribed ganglioneuroma (Figure 3).

Neuroblastomas consist of a diverse set of neuroblastic tumors that include neuroblastomas, ganglioneuro-blastomas, and ganglioneuromas. Ganglioneuromas are the most mature tumors in this spectrum and are considered to be benign[2]. They contain mature neural crest cell-derived Schwann cells and autonomic ganglion cells. They can arise in variable locations, most commonly in the posterior mediastinum, retroperitoneum, or adrenal medulla[1]. These tumors arise in young patients (median age of approximately 7years) and have a slightly higher tendency to occur in women (up to a 1.5:1 ratio has been reported)[2,3]. There is an association with multiple endocrine neoplasia type II and neurofibromatosis type 1[1].

Ganglioneuromas are typically nonfunctional, although they can produce catecholamines, androgens, or vasointestinal peptides[4]. They are usually discovered incidentally on imaging or due to local mass effect because of their indolent growth. In our patient, the size of the mass in a relatively tight space in the epigastrum can explain worsening with motion and epigastric discomfort with posterior radiation (similar to other epigastric pathology such as duodenal ulcer or pancreatitis). Given the nonfunctional status of the tumor, the diarrhea may be unrelated.

On imaging, as shown in Figure 1, ganglioneuromas have well-defined borders and no signs of surrounding invasion or vascular encasement. They can appear as hypoechoic, homogeneous masses on ultrasound examination. Ganglioneuromas are non-enhancing (or have slight enhancement on arterial phase) and low attenuation on CT. Calcifications can be seen in up to 60% of cases[1]. MRI demonstrates hypointensity in T1-weighted imaging and the opposite in T2-weighted imaging.

Due to lack of more distinct radiographic features, biopsies (ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration or imaging-guided core needle biopsy) can provide a histological diagnosis that can guide treatment planning and ideally, complete surgical resection. Indications for surgical resection of these benign tumors include removing functional tumors or those that are symptomatic from mass effect. Ganglioneuromas are benign, noninvasive tumors with excellent prognosis, even if incompletely resected.

In a retrospective series of 146 children with ganglioneuromas or ganglioneuro-blastomas, the only 2 deaths were due to perioperative hemorrhage[5]. However, 22 patients (15%) experienced postoperative complications. There were no malignant transformations in patients with residual tumor burden. Six patients had benign tumor progression during follow-up (median of 7 years). In the subset of 42 histologically-confirmed patients with ganglioneuromas, only one had local progression and remained stable without re-resection.

A similar study by Retrosi et al[6] reported a 30% complication rate and no recurrences or tumor progression in 23 children with ganglioneuromas (26% had incomplete resection). These authors of these 2 studies concluded that survival is not influenced by the extent of tumor resection and that morbidity and mortality are actually due to surgical complications. Therefore, less radical resections to avoid postoperative morbidity are appropriate for these benign tumors.

Although there is typically no vascular invasion present, ganglioneuromas can encase large vessels and be adherent to vital organs in the retroperitoneum. Preoperative imaging is essential for determining if a laparoscopic approach is feasible. A minimally invasive resection can reduce length of stay, time to return to work, pain, and incision size. In addition, it can provide superior visualization for masses in this narrow operative region that contains many major vessels.

There are several case reports in the English language literature that report successful laparoscopic resections of retroperitoneal ganglioneuromas arising from or adjacent to adrenal glands[7-9], abutting inferior mesenteric vessels[10], or near the IVC[11]. A Korean case series outlines 20 laparoscopic resections of non-adrenal retroperitoneal tumors, including 3 ganglioneuromas (one adhered to the IVC)[12]. These patients had reduced hospital stay compared to the open surgery cohort (median of 2.6 d vs 10.6 d, respectively). One operation required conversion to open laparotomy (bleeding) and 2 patients had complications that were treated conservatively. The authors deduced that despite longer operative times, “the presence of adhesions to an adjacent major vessel [present in 50% of their patients] did not affect the clinical outcome”. These reports demonstrate the safety and feasibility of laparoscopic resections for benign retroperitoneal tumors.

There is paucity in the literature, however, of laparoscopic ganglioneuroma resections near the celiac plexus and portal vein. A Japanese case series includes a ganglioneuroma near the root of the left gastric artery and another case series from India describes a ganglioneuroma posterior to the stomach near the celiac axis[13,14]. There is also a 2012 case report from Turkey that presents laparoscopic resection of a mass near the liver hilum and abutting the celiac axis branches[15]. The authors used an initial approach similar to ours to access the tumor and dissected the ganglioneuroma away from the branches of the celiac axis. In our case, the most critical dissection was posterior and caudal to the portal vein. Therefore, after taking down attachments to the common hepatic artery, we relied on altering liver retraction to expose the mass and complete the meticulous dissection without injuring the portal vein.

Preoperative imaging was crucial for planning the operative approach, including trocar placement and defining the relationships and planes between nearby vital structures. Alternating use of ultrasonic energy devices, hook cautery, and blunt dissection facilitated working in a tight space with appropriate hemostasis, despite dense fibrous attachments. Altering traction on the mass and retraction on the liver allowed for excellent visualization and safe dissection near vital vessels.

Preoperative biopsies and high quality preoperative imaging during evaluation of retroperitoneal ganglioneuromas can confirm a diagnosis and rule out malignancy to aid in operative planning and postoperative management. Laparoscopy can enhance visualization of the tumor and its relationships to surrounding structures for optimal dissection. Ultrasonic energy devices and adjusting liver retraction to allow for manipulation of the mass and surrounding structures facilitates safe and effective resection in a tight space. With sufficient experience in laparoscopic surgery and careful patient selection, a minimally invasive approach to removing these rare tumors to prevent postoperative morbidity is appropriate, including near the celiac plexus and the portal vein.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

Author contributions: All authors were involved in the operation, patient care, and manuscript drafting and critical revision; Bingener J was the primary surgeon; Hemmati P performed the literature review.

P-Reviewer: Kumar A, Rubbini M, Vagholkar KR, Wani IA S-Editor: Ji FF L-Editor: A E-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Paasch C, Harder A, Gatzky EJ, Ghadamgahi E, Spuler A, Siegel R. Retroperitoneal paravertebral ganglioneuroma: a multidisciplinary approach facilitates less radical surgery. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14:194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lonergan GJ, Schwab CM, Suarez ES, Carlson CL. Neuroblastoma, ganglioneuroblastoma, and ganglioneuroma: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2002;22:911-934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 458] [Cited by in RCA: 385] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Lucas K, Gula MJ, Knisely AS, Virgi MA, Wollman M, Blatt J. Catecholamine metabolites in ganglioneuroma. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1994;22:240-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Geoerger B, Hero B, Harms D, Grebe J, Scheidhauer K, Berthold F. Metabolic activity and clinical features of primary ganglioneuromas. Cancer. 2001;91:1905-1913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | De Bernardi B, Gambini C, Haupt R, Granata C, Rizzo A, Conte M, Tonini GP, Bianchi M, Giuliano M, Luksch R, Prete A, Viscardi E, Garaventa A, Sementa AR, Bruzzi P, Angelini P. Retrospective study of childhood ganglioneuroma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1710-1716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Retrosi G, Bishay M, Kiely EM, Sebire NJ, Anderson J, Elliott M, Drake DP, Coppi Pd, Eaton S, Pierro A. Morbidity after ganglioneuroma excision: is surgery necessary? Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2011;21:33-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yamaguchi K, Hara I, Takeda M, Tanaka K, Yamada Y, Fujisawa M, Kawabata G. Two cases of ganglioneuroma. Urology. 2006;67:622.e1-622.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sucandy I, Akmal YM, Sheldon DG. Ganglioneuroma of the adrenal gland and retroperitoneum: A case report. N Am J Med Sci. 2011;3:336-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Nasseh H, Shahab E. Retroperitoneal ganglioneuroma mimicking right adrenal mass. Urology. 2013;82:e41-e42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ruiz-Tovar J, Gamallo-Amat C. [Laparoscopic excision of retroperitoneal ganglioneuroma through anterior transperitoneal approach]. Cir Cir. 2012;80:274-277. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Oue T, Yoneda A, Sasaki T, Tani G, Fukuzawa M. Total laparoscopic excision of retroperitoneal ganglioneuroma using the hanging method and a vessel-sealing device. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2008;18:779-782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ahn KS, Han HS, Yoon YS, Kim HH, Lee TS, Kang SB, Cho JY. Laparoscopic resection of nonadrenal retroperitoneal tumors. Arch Surg. 2011;146:162-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sasaki A, Suto T, Nitta H, Shimooki O, Obuchi T, Wakabayashi G. Laparoscopic excision of retroperitoneal tumors: report of three cases. Surg Today. 2010;40:176-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Misra MC, Bhattacharjee HK, Hemal AK, Bansal VK. Laparoscopic management of rare retroperitoneal tumors. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2010;20:e117-e122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Alimoglu O, Caliskan M, Acar A, Hasbahceci M, Canbak T, Bas G. Laparoscopic excision of a retroperitoneal ganglioneuroma. JSLS. 2012;16:668-670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |