Published online Nov 30, 2009. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v1.i1.65

Revised: July 16, 2009

Accepted: July 23, 2009

Published online: November 30, 2009

Esophageal perforations are rare, and traumatic perforations are even more infrequent. Due to the rarity of this condition and its nonspecific presentation, the diagnosis and treatment of this type of perforation are delayed in more than 50% of patients, which leads to a high mortality rate. An 18-year-old male patient was brought to the emergency room with a penetrating neck injury, caused by a gunshot wound. He was taken to the operating room and underwent surgical exploration of the neck and a chest tube was inserted to treat the hemo- and pneumothorax. During the procedure, a 2 cm lesion was detected in the esophagus, and the patient underwent a primary repair. A contrast leakage into his right hemithorax was noticed on the 4th postoperative day; he was submitted to new surgery, and a subtotal esophagectomy and jejunostomy were performed. He was discharged from the hospital in good condition 20 d after the last procedure. The discussion around this topic focuses on the importance of the timing of diagnosis and the subsequent treatment. In early diagnosed patients, more conservative therapeutics should be performed, such as primary repair, while in those with delayed diagnosis, the patient should be submitted to more aggressive and definitive treatment.

- Citation: Fonseca AZ, Ribeiro Jr MAF, Frazão M, Costas MC, Spinelli L, Contrucci O. Esophagectomy for a traumatic esophageal perforation with delayed diagnosis. World J Gastrointest Surg 2009; 1(1): 65-67

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v1/i1/65.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v1.i1.65

Esophageal perforations are rare[1], and traumatic perforations are even more infrequent. In a study by Bladergoreon[2], only 24% of these lesions corresponded to trauma. In 1997, Asensio et al[3] published a series of 43 cases in 6 years. Due to the rarity of this condition and its nonspecific presentation, the diagnosis and treatment of these perforations are delayed in more than 50% of patients[2].

This disorder has a high mortality rate, ranging in the literature from 3%-10% if treated within 24 h of the injury and up to 40%-60% if treated after 24 h[2,4]. Recently, these rates have decreased due to improvements in intensive care units, antibiotics and parenteral nutrition[5].

The high mortality rate is directly associated with the delay in diagnosis[6]. This usually occurs because infection spreads to the mediastinum and lungs, leading to sepsis and multiple organ failure[7].

Several treatment techniques have been reported for this disorder, which indicates that no single surgical procedure could be considered as the gold standard[4]. If the perforation is detected in less than 24 h, the literature supports primary repair and wide drainage of the mediastinum; the treatment for delayed lesions is controversial[4]. Primary repair, single drainage, exclusion procedures, prostheses and resection, with or without primary reconstruction have been described[4].

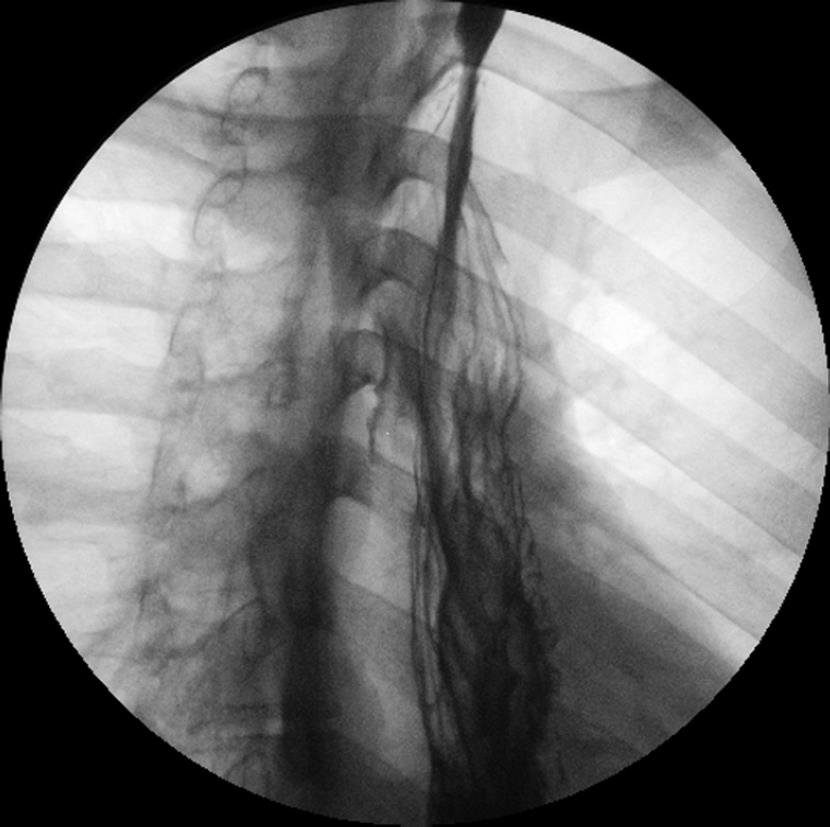

An 18-year-old male patient was brought to the emergency room with a penetrating left side zone I neck injury, caused by a gunshot wound, which had happened 30 min earlier. On physical examination, the bullet exit hole was not identified and auscultation of the breath sounds was diminished in the left hemithorax. At the gunshot entrance site, there was subcutaneous emphysema. He was taken to the operating room and underwent surgical exploration of the neck and a chest tube was inserted to treat the hemo- and pneumothorax. During the procedure, a 2 cm lesion was detected in the esophagus; it was treated with primary repair using a 2 layer interrupted suture. On the 4th postoperative day, an esophagography was performed, where a little contrast leakage into his right hemithorax was noted. As the patient was not recovering as expected, a right thoracotomy was performed. During this surgical procedure, the right lung was incarcerated and a new 4 cm lesion in the esophagus, with necrosis and pus arising from the mediastinum were observed. Due to his bad clinical condition (sepsis and mediastinitis), and despite receiving broad spectrum antibiotics for necrosis of the organ, he underwent a subtotal esophagectomy. A jejunostomy was performed for feeding. The patient was discharged from the hospital 20 d after the last procedure. On his 77th postoperative day, he returned to the service for reconstruction. The surgical approach performed was a gastric tube with a cervical esophagogastric anastomosis with pyloromyotomy. A new esophagography was carried out on the 7th postoperative day, with no signs of leakage. He was discharged on the 14th postoperative day. He has currently been followed up for one year, and is doing well, with good weight gain and normal esophagography (Figure 1).

Esophageal perforation is an infrequent condition, with a high mortality rate. The low incidence of this injury leads to inadequate clinical experience in surgeons[4], and for this reason, appropriate management remains controversial[4].

Many authors agree that for those perforations detected early (less than 24 h from injury), the best treatment is primary repair[1,4,6]. For this group of patients, the mortality rates are lower, with less morbidity compared to patients with delayed diagnosis. Port et al[6] showed a survival rate of 100%, as did Andrade-Alegre[1]; Normando found a 20% mortality rate. Free perforations can be treated by primary repair; if the perforation is large and repair is not feasible, esophageal resection must be performed.

Patients with delayed (more than 24 h) diagnosis represent a serious problem. Generally, they are in a bad clinical condition, needing aggressive and definitive treatment. Most authors think that more aggressive therapy leads to a better outcome. de Andrade et al[8] showed a better survival rate in patients who underwent resection rather than primary repair. Salo et al[9] found a 68% mortality rate after primary repair in these patients compared with 13% in those who underwent esophagectomy. Similar results were demonstrated by Altorjay et al[10] and Orringer et al[11]. The literature strongly recommends that esophagectomy should be performed when a clinical condition, such as sepsis and mediastinitis is encountered[6,8].

Data on the non-operative management of this type of perforation have been published. Vogel et al[12] support this type of therapy, and showed a survival rate of 100%. They claim that once the perforation and pleural contamination are controlled by adequate drainage, it becomes an esophagocutaneous fistula (via chest tube) and will heal similar to most gastrointestinal fistulas. Our group considers that this kind of approach needs to be done with extreme caution and in a selected group of patients, which is small; and as Port et al[6] stated, a high level of vigilance should be maintained, to reverse the decision if necessary.

In conclusion, patients with perforations detected early, can be treated more conservatively, with primary repair of the lesion; for those with delayed diagnosis, the literature suggests more aggressive treatment, where esophagectomy is recommended.

Peer reviewer: Marc D Basson, MD, PhD, Professor and Chair, Department of Surgery, College of Human Medicine, Michigan State University, 1200 East Michigan Avenue, Suite 655, Lansing, MI 48912, United States

S- Editor Li LF L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Lin YP

| 1. | Andrade-Alegre R. Surgical treatment of traumatic esophageal perforations: analysis of 10 cases. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2005;60:375-380. |

| 2. | Bladergroen MR, Lowe JE, Postlethwait RW. Diagnosis and recommended management of esophageal perforation and rupture. Ann Thorac Surg. 1986;42:235-239. |

| 3. | Asensio JA, Berne J, Demetriades D, Murray J, Gomez H, Falabella A, Fox A, Velmahos G, Shoemaker W, Berne TV. Penetrating esophageal injuries: time interval of safety for preoperative evaluation--how long is safe? J Trauma. 1997;43:319-324. |

| 4. | Gupta NM, Kaman L. Personal management of 57 consecutive patients with esophageal perforation. Am J Surg. 2004;187:58-63. |

| 5. | Attar S, Hankins JR, Suter CM, Coughlin TR, Sequeira A, McLaughlin JS. Esophageal perforation: a therapeutic challenge. Ann Thorac Surg. 1990;50:45-49; discussion 50-51. |

| 6. | Port JL, Kent MS, Korst RJ, Bacchetta M, Altorki NK. Thoracic esophageal perforations: a decade of experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:1071-1074. |

| 7. | Normando R, Tavares MAF, Azevedo IU, Modesto A, Janahú AJL. Mediastinitis from perforation and rupture of the thoracic esophagus. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2006;33:361-364. |

| 8. | de Andrade AC, Filho LJFM, Filho MAACL, Alencar AR. Esophagectomy for the esophageal perforation with delayed diagnostic. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2007;34:432-434. |

| 9. | Salo JA, Isolauri JO, Heikkilä LJ, Markkula HT, Heikkinen LO, Kivilaakso EO, Mattila SP. Management of delayed esophageal perforation with mediastinal sepsis. Esophagectomy or primary repair? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1993;106:1088-1091. |

| 10. | Altorjay A, Kiss J, Vörös A, Szirányi E. The role of esophagectomy in the management of esophageal perforations. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;65:1433-1436. |

| 11. | Orringer MB, Stirling MC. Esophagectomy for esophageal disruption. Ann Thorac Surg. 1990;49:35-42; discussion 42-43. |