Published online Aug 15, 2017. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v8.i8.390

Peer-review started: November 3, 2016

First decision: February 15, 2017

Revised: March 12, 2017

Accepted: April 18, 2017

Article in press: April 19, 2017

Published online: August 15, 2017

Processing time: 285 Days and 18.9 Hours

To compare the prevalence of diabetes in patients with schizophrenia treated at a community mental health center with controls in the same metropolitan area and to examine the effect of antipsychotic exposure on diabetes prevalence in schizophrenia patients.

The study was a comprehensive chart review of psychiatric notes of patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder treated at a psychosis program in a community mental health center. Data collected included psychiatric diagnoses, diabetes mellitus diagnosis, medications, allergies, primary care status, height, weight, body mass index (BMI), substance use and mental status exam. Local population data was downloaded from the Centers for Disease Control Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Statistical methods used were χ2 test, Student’s t test, general linear model procedure and binary logistic regression analysis.

The study sample included 326 patients with schizophrenia and 1899 subjects in the population control group. Demographic data showed control group was on average 7.6 years older (P = 0.000), more Caucasians (78.7% vs 38.3%, P = 0.000), and lower percentage of males (40.7% vs 58.3%, P = 0.000). Patients with schizophrenia had a higher average BMI than the subjects in the population control (32.11, SD = 7.72 vs 27.62, SD = 5.93, P = 0.000). Patients with schizophrenia had a significantly higher percentage of obesity (58.5% vs 27%, P = 0.000) than the population group. The patients with schizophrenia also had a much higher rate of diabetes compared to population control (23.9% vs 12.2%, P = 0.000). After controlling for age sex, and race, having schizophrenia was still associated with increased risk for both obesity (OR = 3.25, P = 0.000) and diabetes (OR = 2.42, P = 0.000). The increased risk for diabetes remained even after controlling for obesity (OR = 1.82, P = 0.001). There was no difference in the distribution of antipsychotic dosage, second generation antipsychotic use or multiple antipsychotic use within different BMI categories or with diabetes status in the schizophrenia group.

This study demonstrates the high prevalence of obesity and diabetes in schizophrenia patients and indicates that antipsychotics may not be the only contributor to this risk.

Core tip: This study compares obesity and diabetes rates between schizophrenia patients treated in a community mental health center and a local population control. It demonstrates that prevalence of obesity and diabetes is significantly higher in patients with schizophrenia, which is consistent with previous research. In this cross-sectional study, second generation antipsychotic use and antipsychotic dosage were not correlated with obesity categories or diabetes status. This implies that antipsychotics alone may not be responsible for the increased diabetes risk in schizophrenia patients. Many factors may contribute to risk, including an inherent vulnerability to diabetes in schizophrenia patients that has been seen in earlier studies.

- Citation: Annamalai A, Kosir U, Tek C. Prevalence of obesity and diabetes in patients with schizophrenia. World J Diabetes 2017; 8(8): 390-396

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v8/i8/390.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v8.i8.390

It is now well established that people with serious mental illness (SMI), including schizophrenia, have excess morbidity and mortality leading to a reduced lifespan of 20-25 years compared with the rest of the population[1,2]. The increased mortality is largely attributable to physical illness, including metabolic abnormalities and cardiovascular disease, rather than factors that are directly associated with psychiatric illness such as suicide or homicide.

Schizophrenia is seen in approximately 1% of the population. The rates of obesity and diabetes in patients with schizophrenia are higher than the general population[3]. Obesity is reported in approximately 50% patients, metabolic syndrome is reported in up to 40%, glucose intolerance in up to 25% and diabetes in up to 15% patients with schizophrenia[4]. The cause for the increased prevalence of these conditions is multifactorial. Antipsychotics, a cornerstone of treatment in people with schizophrenia, cause weight gain, glucose intolerance and other metabolic complications. Second generation antipsychotics, notably clozapine and olanzapine, are associated with a 5-fold increase in metabolic syndrome after three years of treatment[5]. Patients with schizophrenia are known to have unhealthy diets and inadequate physical activity[6] due to lower socioeconomic status, lower educational level, and sub-optimal living situations. Symptoms of schizophrenia such as low motivation, apathy and cognitive deficits also could play a role in preventing access to high quality health care.

An additional important contributing factor to the increased prevalence of diabetes in schizophrenia may be an inherent susceptibility to diabetes in people with schizophrenia. Patients with schizophrenia have an increased risk of diabetes in family members[7,8]. Also, parental diabetes is a significant predictor of diabetes in people with psychotic disorders[8]. Inflammatory markers are seen in both schizophrenia and metabolic syndrome and the increased inflammation may explain the association between these conditions[9].

A recent meta-analysis of metabolic parameters in first episode psychosis patients demonstrated increased insulin resistance and impaired glucose tolerance when compared to controls[10]. However, an earlier review of diabetes in first episode patients showed that established diabetes was much less common in first-episode psychosis patients compared to those already on antipsychotics[11]. People with schizophrenia may have increased vulnerability manifesting as pre-diabetes that is compounded by cumulative exposure to antipsychotic medications.

The purpose of this study is to compare the prevalence of obesity and diabetes in patients with schizophrenia treated at a community mental health center with population controls in the same metropolitan area. The authors hypothesized that the prevalence would be higher in patients with schizophrenia. The study also examines the effect of antipsychotic exposure on diabetes prevalence in schizophrenia patients.

Comprehensive psychiatric review notes of consecutive patients followed at Connecticut Mental Health Center (CMHC) Psychosis Program within a one-year period were audited. The study was approved by the Yale Human Investigations Committee. Inclusion criterion was a chart diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder verified by the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-IV (SCID for DSM-IV). CMHC Psychosis Program is a diagnosis specific, multidisciplinary outpatient clinic and research program, which serves community dwelling, low-income adult patients diagnosed with a non-affective psychosis. The program is the major point of care for psychotic patients who dwell in the Greater New Haven area, an urban catchment area with an estimated census of 200000 people. The program itself has a census ranging 450 to 500 patients, with about 5% annual turnover rate.

Comprehensive psychiatric review is a 30-50 min full psychiatric examination of established patients by one of four physicians and one advanced practice nurse. Notes are recorded in an institution specific standard form, and requires recording of all diagnoses, all medications, allergies, primary care and physical/gynecological exam status, review of systems, height, weight, body mass index (BMI), substance use, and mental status information. Per Psychosis Program policies, every patient is weighed before the exam with the same scale calibrated regularly and height is measured at least once with the same scale during patients’ tenure in the clinic. While waist circumference is a better indicator of abdominal obesity and subsequent cardiovascular risk, it is not clear that it offers additional information for clinical management. Also it is not part of usual clinical care due to provider discomfort[12]. Hence, BMI was used as an index for obesity in this study. Diabetes mellitus (DM) type 2 diagnosis was extracted from the chart by self-report and verified by obtaining primary care records. In addition, patients were screened at least yearly for diabetes by glycosylated hemoglobin (Hba1c) and referred for treatment if they tested positive.

The control group is local population in Greater New Haven metro area and data are downloaded from United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance System (BRFSS)[13]. BRFSS is an ongoing telephone health survey tracking health conditions and risk behaviors in the United States. Details are described at http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/. Latest local data was from 2012.

De-identified patient and population data was merged in an SPSS v.22 data file, and corresponding variables recoded for compatibility. Categorical data was compared with χ2 test, continuous data with Student’s t test. General linear model (GLM) procedure was utilized to explore the relationship between BMI and schizophrenia while controlling for demographic factors. Binary logistic regression analysis was utilized to calculate adjusted odds ratios.

The study sample included 326 patients with schizophrenia and 1899 subjects in control group of local population. Demographic data for the population control and schizophrenia as well as clinical data for the schizophrenia subjects is presented in Table 1. Control group was on average 7.6 years older (t = 7.36, P = 0.000), included more subjects that identified themselves as Caucasian (78.7% vs 38.3%, χ2 = 228.35, P = 0.000), and had lower percentage of males (40.7% vs 58.3%, χ2 = 35.02, P = 0.000).

| Schizophrenia | Population control | |

| n | 326 | 1899 |

| Agea | 47.47 (± 26) | 55.13 (± 18.21) |

| Sex (% male)b | 58.30% | 40.70% |

| Racec | ||

| White | 38.30% | 78.70% |

| Black | 49.70% | 9.50% |

| Hispanic | 6.40% | 7.90% |

| Other | 1.80% | 3.90% |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Schizophrenia | 7% | |

| Schizoaffective | 23.30% | |

| Antipsychotic medication (n = 306) | ||

| First generation | 81 (26.5%) | |

| Second generation | 194 (63.4%) | |

| Both | 31 (10.1%) | |

| Multiple antipsychotic use | 59 (2.7%) | |

| Chlorpromazine equivalent dose | 667.0 (± 507.9) |

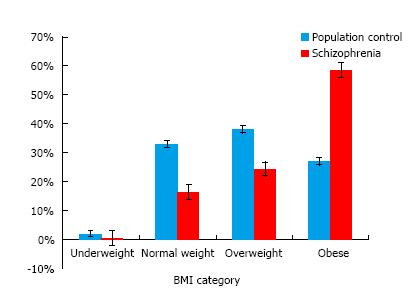

Subjects with schizophrenia had a higher average BMI (32.11, SD = 7.72) than the subjects in the control group (27.62, SD = 5.93). The difference was highly significant (4.49, 95%CI: 3.75, 5.23; T = 11.83, P = 0.000). When BMI categories were examined, schizophrenia group had a significantly higher percentage of obesity than the control group (58.5% vs 27%), and the control group had a higher percentage of normal and overweight subjects (Figure 1, χ2 = 125.14, P = 0.000). When obesity categories were examined among the obese subjects, schizophrenia group had a higher percentage of Class 2 and 3 obesity (i.e., BMI between 35 to 40 and BMI > 40 respectively) than the control group (Figure 2, χ2 = 6.13, P < 0.05). Within the schizophrenia group, antipsychotic medication dosage was not significantly correlated with BMI either in the entire group or the obese group (P = 0.93 and 0.92 respectively). Also, there was no difference in the distribution of second generation antipsychotic use or multiple antipsychotic use within different BMI categories in the schizophrenia group (P = 20.24 and 0.19 respectively). Based on these findings, medication variables were dropped out of multivariable tests.

Given the differences between two groups in demographics, a univariate analysis was conducted and GLM procedure used to control for age, sex, and race. After controlling for these demographic variables, schizophrenia group still had a highly significant association with higher BMI (F = 26.78, df = 1, P = 0.003). None of the other variables, or interactions with demographic variables, were significant. Following this, a binary logistic regression analysis was conducted to calculate predictive value of schizophrenia status for obesity after age, sex and race controlled, and schizophrenia status remained significant with an odds ratio of 3.25 (95%CI: 2.47, 4.29, P = 0.000).

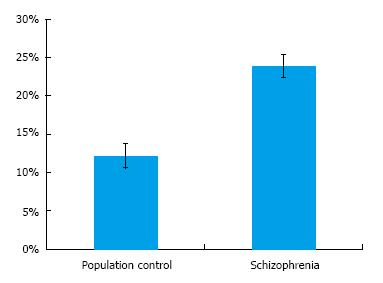

Next, diabetes mellitus status was examined in the sample. Schizophrenia group had a much higher rate of diabetes compared to control group (Figure 3, 23.9% vs 12.2%, χ2 = 31.81, P = 0.000). Within the schizophrenia group, there were no statistically significant differences between diabetics and non-diabetics in rates of second generation antipsychotic use, multiple antipsychotic medication use or chlorpromazine equivalent daily antipsychotic dosage. Based on these findings, medication terms were dropped from multivariable analyses. Following this, a binary logistic regression procedure was conducted to control for demographic variables of age, sex and race to examine the relationship between schizophrenia and diabetes. Higher age (P = 0.000) and non-Caucasian race (P = 0.000) was significantly predictive of diabetes status and male sex approached significance (P = 0.07). After controlling for these demographic factors, schizophrenia remained highly associated with diabetes with an odds ratio of 2.42 (95%CI: 1.75, 3.36, P = 0.000). Since obesity is closely associated with diabetes, one more regression analysis was performed including first BMI, and then obesity status (Table 2) and schizophrenia still remained highly significantly associated with diabetes.

| B | S.E. | Wald | Df | P | Odds ratio | 95%CI for Odds ratio | ||

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| Age | 0.36 | 0.005 | 61.88 | 1 | 0 | 1.036 | 1.027 | 1.045 |

| Sex (male) | 0.34 | 0.133 | 6.51 | 1 | 0.011 | 1.405 | 1.082 | 1.825 |

| Race (non-white) | 0.52 | 0.156 | 11.29 | 1 | 0.001 | 1.689 | 1.224 | 2.292 |

| Obesity | 1.25 | 0.137 | 84.61 | 1 | 0 | 3.514 | 2.689 | 4.593 |

| Schizophrenia | 0.6 | 0.179 | 11.31 | 1 | 0.001 | 1.825 | 1.285 | 2.59 |

In this study, patients with schizophrenia had a significantly higher average BMI, higher percentage of people with class 2 and class 3 obesity and higher percentage of people with diabetes, compared to the general population. The association for both obesity and diabetes remained after controlling for differences in demographic variables between the two groups. Having schizophrenia was associated with more than a 3-fold risk of obesity and more than a 2-fold risk of diabetes.

These results are consistent with what is known about the increased risk for metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia. But a notable finding is that after controlling for BMI and obesity status, the risk of diabetes remained significant, though lower. Though pathways of diabetes development are thought to be the largely the same as those causing obesity, diabetes can occur without weight gain in patients on antipsychotic medications[14]. It is postulated that antipsychotics may to some extent affect glucose regulation independent of their effect on weight.

In this study design, medication variables for the general population were unknown and could not be compared with the schizophrenia group. Within the schizophrenia group, antipsychotic dose, second generation antipsychotics and use of multiple antipsychotic medications did not vary between the different categories of obesity or with diabetes status. It is notable that antipsychotic medication factors did not account for the differences in either obesity or diabetes status within the schizophrenia group. Neither the antipsychotic category nor the medication dose correlated with obesity. The strong risk of obesity and diabetes in schizophrenia coupled with lack of differential effects between antipsychotic medications and persistent risk of diabetes after controlling for obesity in this sample indicates some of the risk may be due to factors other than medications. Many other factors including an innate risk may be responsible for the higher prevalence of obesity and diabetes in the schizophrenia population. An inherent susceptibility to diabetes in schizophrenia patients is supported by studies with medication naive first episode psychosis patients[10]. The inherent risk for diabetes may be mediated in part by elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines seen in both schizophrenia and obesity[9]. On the other hand, cross sectional data may not be sufficient to unravel the complicated relationship between schizophrenia, antipsychotic medications, obesity and diabetes since patients go through medication changes over the course of the disease.

Other factors may affect these results. The survey data from BRFSS is based on self-report by metropolitan area residents. People may have undiagnosed diabetes and tend to underestimate and underreport obesity. Patients with schizophrenia have increased contact with health care leading to higher likelihood of diabetes screening during mental health treatment. However, the increased prevalence of diabetes seen in this study is consistent with earlier reports and is unlikely to result from a screening bias given that historically people with SMI have low rates of screening and treatment for metabolic conditions[15].

This study did not find a correlation between second generation antipsychotics and obesity and diabetes status. It may be that the differential effects of first and second generation antipsychotics on metabolic syndrome are not as different as previously believed. Indeed, the rates of metabolic syndrome between first and second generation antipsychotics are not significant when clozapine and olanzapine are excluded[5]. A meta-analysis of antipsychotic-induced weight gain in first episode psychosis patients showed that most antipsychotic medications, including first generation medications like haloperidol, are associated with some weight gain[16].

An innate predisposition to diabetes, seen in first episode psychosis patients, may be compounded by antipsychotic medications, lower socioeconomic status and decreased access to quality health care. Patients with schizophrenia also are less physically active contributing further to insulin resistance. Antipsychotics alone may not account for the high metabolic burden seen in chronic schizophrenia patients and high mortality rates. In fact, antipsychotic use is associated with overall lower mortality, especially when highly effective medications like clozapine are used for treating schizophrenia[17].

Strengths of this study include the large naturalistic sampling of community dwelling schizophrenia patients as well as a local population control sample in the same geographic area. Patients were not recruited for the study, instead all patients in the Psychosis Program with diagnosis of schizophrenia were included. This study design allows for applicability of results to real world settings. In the community mental health center sample, schizophrenia diagnosis was based on a structured interview and diabetes diagnosis was established based on previous lab diagnosis. A limitation is that the BRFSS survey data was based on self-report. Also the antipsychotic use is cross sectional and results may be confounded by changes in the type of antipsychotic used throughout patients’ disease history. Since this was not a controlled study, demographic variables were different between the disease and control groups. While these may confound results, in our study, higher prevalence of obesity and diabetes in schizophrenia persisted after controlling for these variables.

In conclusion, this study is consistent with previous research showing significantly increased prevalence of obesity and diabetes in people with schizophrenia. The risk for diabetes is present even when weight is controlled for as a causative factor. Antipsychotics contribute to the burden of diabetes but may not be the primary cause. Since schizophrenia patients are associated with a very high risk of diabetes, clinicians should be vigilant about screening and monitoring patients for diabetes from the beginning of treatment.

The Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services supports all research activities at Connecticut Mental Health Center. The authors would also like to acknowledge their patients who are the source for the data and colleagues and resident psychiatrists who provide care and contribute clinical data.

People with serious mental illness (SMI), including schizophrenia, have excess morbidity and mortality compared with the rest of the population, largely attributable to physical illness, including metabolic abnormalities and cardiovascular disease. The rates of obesity and diabetes in patients with schizophrenia are higher than the general population. The cause for the increased prevalence of these conditions is multifactorial. Antipsychotics, unhealthy diets, inadequate physical activity due to lower socioeconomic status, lower educational level, and sub-optimal living situations and symptoms such as low motivation, apathy and cognitive deficits could all play a role in increased metabolic risks in this population. An additional important contributing factor to the increased prevalence of diabetes in schizophrenia may be an inherent susceptibility to diabetes in people with schizophrenia. People with schizophrenia may have increased vulnerability manifesting as pre-diabetes that is compounded by cumulative exposure to antipsychotic medications. This study compares the prevalence of obesity and diabetes in schizophrenia patients treated at a community mental health center with controls in the same metropolitan area. The study also examines the effect of antipsychotic exposure on diabetes prevalence in schizophrenia patients.

Many studies show there may be an inherent risk for diabetes in schizophrenia patients as evidenced by increased insulin resistance in patients with new onset of psychosis. Inflammatory pathways seen in both schizophrenia and people with obesity and diabetes may mediate some of this risk. The pathways leading to obesity and those leading to diabetes are not well differentiated. All these are important areas for further research. The detrimental effect of antipsychotics on weight and insulin resistance is well known. However, the extent of this risk compared to other factors is not clear. The contribution of various known risk factors on development of metabolic syndrome in people with schizophrenia is an area for further study.

More and more studies are establishing that there is a high prevalence of obesity and diabetes in schizophrenia. There is emerging evidence that some risk of diabetes may be present independent of weight. The present study adds to existing evidence that antipsychotics, while contributing to burden of diabetes, are not the only cause.

This naturalistic study is consistent with existing research that shows high prevalence of obesity and diabetes in schizophrenia patients. The risk of diabetes appears to be mediated not only by weight gain but other factors. Hence, not only weight but also diabetes screening should be prioritized in schizophrenia populations. Also this should be done regardless of whether they are on antipsychotic medications or not. Clinicians should be vigilant about early detection and treatment. Many studies in people after the first episode of psychosis demonstrate that early detection and treatment of obesity and diabetes may improve morbidity and mortality.

First generation antipsychotics refer to a group of antipsychotics used to treat schizophrenia, whose primary mechanism of action is via dopamine. Second generation antipsychotics refer to antipsychotics that were developed later and have pharmacologic actions on both dopamine and serotonin. The latter group is generally considered to carry a higher risk for metabolic syndrome.

The manuscript is well written and concise.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Endocrinology and metabolism

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Bharaj P, Chakrabarti S, Koch TR, Masaki T, Tarantino G S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Brown S. Excess mortality of schizophrenia. A meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:502-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 620] [Cited by in RCA: 575] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3:A42. [PubMed] |

| 3. | DE Hert M, Schreurs V, Vancampfort D, VAN Winkel R. Metabolic syndrome in people with schizophrenia: a review. World Psychiatry. 2009;8:15-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 428] [Cited by in RCA: 436] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Annamalai A, Tek C. An overview of diabetes management in schizophrenia patients: office based strategies for primary care practitioners and endocrinologists. Int J Endocrinol. 2015;2015:969182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | De Hert M, Schreurs V, Sweers K, Van Eyck D, Hanssens L, Sinko S, Wampers M, Scheen A, Peuskens J, van Winkel R. Typical and atypical antipsychotics differentially affect long-term incidence rates of the metabolic syndrome in first-episode patients with schizophrenia: a retrospective chart review. Schizophr Res. 2008;101:295-303. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Ratliff JC, Palmese LB, Reutenauer EL, Liskov E, Grilo CM, Tek C. The effect of dietary and physical activity pattern on metabolic profile in individuals with schizophrenia: a cross-sectional study. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53:1028-1033. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mukherjee S, Schnur DB, Reddy R. Family history of type 2 diabetes in schizophrenic patients. Lancet. 1989;1:495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Miller BJ, Goldsmith DR, Paletta N, Wong J, Kandhal P, Black C, Rapaport MH, Buckley PF. Parental type 2 diabetes in patients with non-affective psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2016;175:223-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Beumer W, Drexhage RC, De Wit H, Versnel MA, Drexhage HA, Cohen D. Increased level of serum cytokines, chemokines and adipokines in patients with schizophrenia is associated with disease and metabolic syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37:1901-1911. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Perry BI, McIntosh G, Weich S, Singh S, Rees K. The association between first-episode psychosis and abnormal glycaemic control: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:1049-1058. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mitchell AJ, Vancampfort D, De Herdt A, Yu W, De Hert M. Is the prevalence of metabolic syndrome and metabolic abnormalities increased in early schizophrenia? A comparative meta-analysis of first episode, untreated and treated patients. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39:295-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Barber J, Palmese L, Chwastiak LA, Ratliff JC, Reutenauer EL, Jean-Baptiste M, Tek C. Reliability and practicality of measuring waist circumference to monitor cardiovascular risk among community mental health center patients. Community Ment Health J. 2014;50:68-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Centers for Disease Control Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Atlanta, GA. [updated 2016 Aug 26; cited 2012]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/brfss. |

| 14. | Jin H, Meyer JM, Jeste DV. Phenomenology of and risk factors for new-onset diabetes mellitus and diabetic ketoacidosis associated with atypical antipsychotics: an analysis of 45 published cases. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2002;14:59-64. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Correll CU, Druss BG, Lombardo I, O’Gorman C, Harnett JP, Sanders KN, Alvir JM, Cuffel BJ. Findings of a U.S. national cardiometabolic screening program among 10,084 psychiatric outpatients. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61:892-898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tek C, Kucukgoncu S, Guloksuz S, Woods SW, Srihari VH, Annamalai A. Antipsychotic-induced weight gain in first-episode psychosis patients: a meta-analysis of differential effects of antipsychotic medications. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2016;10:193-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tiihonen J, Lönnqvist J, Wahlbeck K, Klaukka T, Niskanen L, Tanskanen A, Haukka J. 11-year follow-up of mortality in patients with schizophrenia: a population-based cohort study (FIN11 study). Lancet. 2009;374:620-627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 800] [Cited by in RCA: 805] [Article Influence: 50.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |