Published online Nov 15, 2016. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v7.i19.554

Peer-review started: February 14, 2016

First decision: April 15, 2016

Revised: May 20, 2016

Accepted: June 14, 2016

Article in press: June 16, 2016

Published online: November 15, 2016

Processing time: 280 Days and 3.2 Hours

To systematically review the literature on women with both diabetes in pregnancy (DIP) and depression during or after pregnancy.

In this systematic literature review, PubMed/MEDLINE and EMBASE were searched (13 November 2015) using terms for diabetes (type 1, type 2, or gestational), depression, and pregnancy (no language or date restrictions). Publications that reported on women who had both DIP (any type) and depression or depressive symptoms before, during, or within one year after pregnancy were considered for inclusion. All study types were eligible for inclusion; conference abstracts, narrative reviews, nonclinical letters, editorials, and commentaries were excluded, unless they provided treatment guidance.

Of 1189 articles identified, 48 articles describing women with both DIP and depression were included (sample sizes 36 to > 32 million). Overall study quality was poor; most studies were observational, and only 12 studies (mostly retrospective database studies) required clinical depression diagnosis. The prevalence of concurrent DIP (any type) and depression in general populations of pregnant women ranged from 0% to 1.6% (median 0.61%; 12 studies). The prevalence of depression among women with gestational diabetes ranged from 4.1% to 80% (median 14.7%; 16 studies). Many studies examined whether DIP was a risk factor for depression or depression was a risk factor for DIP. However, there was no clear consensus for either relationship. Importantly, we found limited guidance on the management of women with both DIP and depression.

Given the increasing prevalence of diabetes and depression, high-quality research and specific guidance for management of pregnant women with both conditions are warranted.

Core tip: Depression in women with diabetes in pregnancy (DIP) may be increasingly common. We identified 48 studies of depression and DIP, of variable and often poor quality. The prevalence of concurrent DIP and depression ranged from 0% to 1.6% (median 0.61%; 12 studies). Among women with gestational diabetes, the prevalence of depression ranged from 4.1% to 80% (median 14.7%; 16 studies). There was no clear consensus on whether DIP was a risk factor for depression. Given the increasing prevalence of diabetes and depression, high-quality research and specific guidance for management of pregnant women with both conditions are warranted.

- Citation: Ross GP, Falhammar H, Chen R, Barraclough H, Kleivenes O, Gallen I. Relationship between depression and diabetes in pregnancy: A systematic review. World J Diabetes 2016; 7(19): 554-571

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v7/i19/554.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v7.i19.554

Diabetes affects an increasing number of pregnancies worldwide. In 2015, almost 21 million births (16.2%) were affected by hyperglycemia during pregnancy[1,2]. Approximately 10% to 15% of these births involved mothers with pre-existing or newly detected type 1 or type 2 diabetes, with the remaining 85% to 90% being women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM)[1,2]. As the prevalence of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes in the general population is increasing[1], the number of women affected by diabetes in pregnancy (DIP) is also rising. Indeed, between 2000 and 2010, the age-standardized prevalence of pregnancies in the United States affected by type 1 or type 2 diabetes increased by 37%[3] and the prevalence of GDM increased by 56%[4]. Diabetes in pregnancy can have adverse effects on both the mother and child, including increased risk of miscarriage, stillbirth, preterm delivery, pre-eclampsia, cesarean section delivery, postpartum development of type 2 diabetes in women with GDM, congenital malformations, fetal macrosomia, neonatal hypoglycemia, neonatal respiratory distress, and obesity and insulin resistance in childhood, followed by impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes later in life[1,5,6].

Depression during pregnancy or postpartum also adversely affects women and their children. Depression during pregnancy is associated with poorer maternal health, increased likelihood of obstetric complications, preterm birth, and neonatal complications[5,6]. Postpartum depression is associated with difficulties with maternal-child bonding, inadequate care of the child, and lower rates of breastfeeding[7].

Recent evidence suggests a bidirectional relationship between diabetes and depression among non-pregnant patients. Several meta-analyses of longitudinal studies suggest that diabetes is a risk factor for the development of depression[8-10]. Conversely, depression has been suggested as a risk factor for the development of type 2 diabetes[11,12]. In addition, the prevalence of comorbid diabetes and depression is higher than expected, leading to speculation that diabetes and depression may share underlying biological mechanisms[10,13]. However, evidence for a link between DIP and depression during pregnancy or postpartum is limited[5]. Pregnancy represents a potentially stressful event, which could make women with pre-existing diabetes more vulnerable to depression. Similarly, a diagnosis of GDM could contribute to depressive symptoms, particularly during pregnancy. Importantly, depression is associated with poor diabetes self-care[14], which may be more challenging during pregnancy and postpartum when diabetes management and glycemic control are especially complex[15]. Indeed, women with DIP and depression may struggle to cope with the physical and psychological demands of pregnancy and early motherhood. Given the increasing prevalence of both diabetes and depression among women of childbearing years, the co-occurrence of both conditions during pregnancy or postpartum is likely to become more common. Despite this increase, and the impression among many clinicians that depression in pregnant or postpartum women with diabetes is common, current major guidelines for the treatment and management of DIP[15-17] or depression[18,19] do not provide adequate advice regarding care of these patients.

The aim of this systematic literature review was to assess the current knowledge regarding the prevalence, treatment, and management of women who have both DIP and depression before, during, or after pregnancy.

We searched MEDLINE (PubMed) and EMBASE on 13 November 2015, using Medical Subject Heading (MeSH), EMTREE, or free-text terms: (pregnancy OR postpartum period OR pregnant OR postnatal OR post-natal OR antenatal) AND (depression OR depressive disorder, major OR major depression OR depression, postpartum OR puerperal depression OR major depressive disorder OR MDD OR postnatal depression) AND (diabetes mellitus OR diabetes mellitus, type 1 OR diabetes mellitus, type 2 OR diabetes, gestational OR insulin dependent diabetes OR non insulin dependent diabetes OR pregnancy diabetes mellitus OR diabetic OR juvenile diabetes OR type 1 diabetes OR type I diabetes OR insulin-dependent diabetes OR type 2 diabetes OR type II diabetes OR non-insulin dependent diabetes OR NIDDM OR gestational diabetes). Searches were tailored to each database and restricted to human studies. There were no restrictions on publication date, publication type, or language.

Publications that reported on women who had both DIP (type 1, type 2, or GDM) and depression or depressive symptoms before, during, or within one year after pregnancy were considered for inclusion. All study types were eligible for inclusion, including meta-analyses, systematic reviews, randomized and nonrandomized clinical trials, observational studies (prospective and retrospective), case reports, clinical practice guidelines, and other publications providing guidance on diagnosis, treatment, or management.

Publications were excluded if they described studies not conducted in humans, studies in which data for women with DIP and depression were pooled with data for women with other conditions, studies that reported depressive symptoms based on measures of anxiety or bipolar disorder, or studies that only reported fetal or newborn outcomes (i.e., no maternal outcomes or prevalence data). Conference abstracts, narrative reviews, systematic reviews that did not report original data, nonclinical letters, editorials, and commentaries were excluded, unless they provided treatment guidance.

One person (medical writer contracted by Eli Lilly and Company) conducted the literature search and screened the titles and abstracts of retrieved publications using the predefined eligibility criteria. The full text of publications identified for potential inclusion were rescreened using the same criteria. Reference lists of reviews and other relevant publications were screened to identify additional publications. All authors reviewed and approved the publications identified for inclusion.

The medical writer extracted all relevant data, including publication type and year, study design, study objectives, country of origin, sample size, patient characteristics, diabetes type(s), definition or measures of depression, and main outcomes, from the included publications. The risk of bias was assessed by study quality components (study design, sample size, outcomes) and by the depression and diabetes definitions used in each study. Because information on this topic is lacking, all levels of evidence were included in the review.

Outcome measures included: Incidence/prevalence of DIP and depression among pregnant or postpartum women; relationship between DIP and depression; relative risk of developing depression during or after pregnancy among women with DIP vs pregnant women without diabetes; relative risk of developing GDM among women with depression vs women without depression; clinical or demographic factors related to increased risk of having both DIP and depression during or after pregnancy; methods of diagnosis or measurement of depression; and treatment/management strategies.

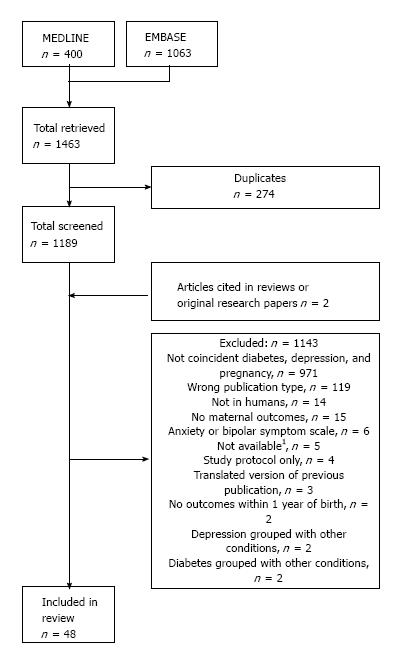

A total of 1463 publications were retrieved from MEDLINE and EMBASE; after removal of duplicates, 1189 publications were screened (Figure 1). Of these, 46 publications were selected for inclusion[20-65]. Manual screening of bibliographies identified two additional relevant studies[66,67]. Overall, 48 publications were included in this review (Figure 1, Tables 1-3, Supplementary Table 1). Of these, 30 described prospective observational studies[20,21,23,24,26,27,29-31,34,35,37,38,41,43-45,47-49,51,54,57,58,60-62,65-67], 15 described retrospective observational studies[22,25,28,32,39,40,42,46,50,53,55,56,59,63,64], and three described randomized controlled trials (RCTs)[33,36,52], two of which reported only baseline data[36,52]. Two publications described the same study, but reported different subgroup analyses[23,29].

| First author,study design | Definition/measures of depression | Timing of depression measures | Overall, nsubgroups, n | Main outcomes/findings |

| Abdollahi[20] Prospective, cohort | EPDS ≥ 12 | Within 12 wk after delivery | n = 1449 | Women with GDM had greater risk of postpartum depression than women without GDM [adjusted OR (95%CI): 2.93 (1.46-5.88), P = 0.002] |

| 1Bener[23] Prospective, cross-sectional | EPDS ≥ 12 | Within 6 mo after delivery | n = 1379 With depression, n = 243; Without depression, n = 1136 | Prevalence of GDM was numerically, but not statistically, higher in women with depression (9.9%) vs women without depression (6.2%) (P = 0.051) |

| Berger[25] Retrospective | EPDS ≥ 13 or did not answer “No” to self-harm question | Within 4 d after delivery | Unselected, n = 322 History of mental illness, n = 215 | In the unselected group, prevalence of GDM was higher in women with postpartum depression (27.3%) vs women without depression (9.0%) (P = 0.04); there was no difference in the group with previous mental illness (19.4% vs 10.2%, P = 0.14) In the unselected group, GDM was associated with postpartum depression [OR (95%CI): 12.1 (1.9-77.8)] In the unselected group, overall prevalence of depression and GDM was 0.9% (3 of 322) |

| Bisson[26] Prospective, case-control | EPDS ≥ 10 | Approx. 30 wk gestation | n = 52 GDM, n = 26; No GDM, n = 26 | Women with GDM had a greater prevalence of depressive symptoms vs women without GDM (23% vs 0%, P = 0.023) Mean (SD) EPDS score was 6.8 (4.0) for women with GDM and 4.2 (2.6) for women without GDM (P < 0.05) |

| Blom[27] Prospective | EPDS > 12 | 2 mo after delivery | n = 4941 With depression, n = 396; Without depression, n = 4545 | No significant difference in the proportion of women with GDM between those who did (4/396; 1.0%) and did not (28/4545; 0.6%) have depression (P≥ 0.05) Calculated prevalence of women with both GDM and depression = 0.08% (4/4941) |

| Bowers[28] Retrospective | ICD9 codes 296.2, 296.3, and 311 | Coded on medical history or hospital discharge record | n = 128295 With depression, n = 5815 (medical history, n = 5350); Without depression, n = 122480 | Women with history of depression were more likely to have GDM than women without history of depression (5.4% vs 4.3%; P value NR) Depression was associated with significantly increased risk of GDM [OR (95%CI): adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, study site, insurance, and parity: 1.42 (1.26-1.60)]; similar results when restricted to women with history of pre-pregnancy depression [adjusted OR (95%CI): 1.36 (1.20-1.54)] Calculated prevalence of coincident GDM and depression was 313 of 128295 (0.24%) |

| 1Burgut[29] Prospective, cross-sectional | EPDS ≥ 12 | Within 6 mo of delivery | n = 1379 Qatari women, n = 837 Other Arab women, n = 542 With depression, n = 243 With history of diabetes, n = 310 | GDM increased risk of depression in Qatari women [adjusted OR (95%CI): 1.65 (1.02-2.69)], but not in other Arab women [1.09 (0.63-1.91)] |

| Chazotte[31] Prospective | CES-D ≥ 16 | Weeks 34-36 of gestation | n = 90 GDM, n = 30; High risk of preterm birth, n = 30 | 56.7% of women with GDM had CES-D ≥ 16; this was not significantly different vs women at low (33.3%) or at high (70%) risk of preterm birth (P≥ 0.05) Mean (SD) CES-D score was 17.0 (9.1) for women with GDM, 20.9 (9.4) for women at high risk of preterm birth, and 13.7 (7.5) for women at low risk of preterm birth (P≥ 0.05) |

| Crowther[33] RCT | EPDS ≥ 12 | 3 mo after delivery | Low risk of preterm birth, n = 30 n = 1000 Intervention2, n = 490; Routine care, n = 510 | Significantly lower proportion of women in the intervention group (8%; 23/278 respondents) had EPDS indicative of depression vs women in the routine care group (17%; 50/295 respondents) (P = 0.001) |

| Dalfra[34] Prospective | CES-D ≥ 16 | 3rd trimester and 8 wk after delivery | n = 245 GDM, n = 176 (treated with diet, n = 109; treated with insulin, n = 68); No DM, n = 39 | Mean (SD) CES-D scores at 3rd trimester were 17.0 (8.6) among women with GDM and 18.0 (8.7) among women without DM (P = 0.52) Mean (SD) CES-D scores at 3rd trimester were 16.6 (8.1) among women with GDM treated with diet and 17.7 (9.4) among women with GDM treated with insulin (P = 0.58) The severity of depressive symptoms increased from the 3rd trimester to after delivery in women with GDM [estimated mean difference in CES-D score (95%CI): 5.7 (4.2-7.3)], but decreased in women without DM [2.7 (-5.9-0.5); P < 0.0001 between groups] |

| Daniells[35] Prospective, longitudinal | MHI-5 ≥ 16 | Weeks 30 and 36 of gestation, and 6 wk after delivery | n = 100 GDM, n = 50; No GDM, n = 50 | Significantly higher proportion of women with GDM (30%) were depressed at Week 30 vs women who did not have GDM (12%) [OR (95%CI): 3.14 (1.1-8.94), P = 0.03]; however, there was no difference at Week 36 or after delivery (P≥ 0.05) Mean (SD) MHI-5 scores: Week 30: GDM, 13.9 (4.8); no GDM, 11.4 (3.8), P = 0.004; Week 36: GDM, 10.9 (3.8); no GDM, 11.7 (4.0), P = 0.31; postpartum: GDM, 11.5 (4.5); no GDM, 11.7 (4.0), P = 0.79 No significant difference in MHI-5 scores in women who were being treated with insulin (n = 7) compared with those being managed with diet only (P = 0.06; MHI-5 scores NR) |

| de Wit[36] Analysis of baseline RCT data | WHO-5 < 50 | Early pregnancy (< 20 wk) | n = 98 obese women Depressed, n = 26 | Prevalence of GDM was 13.5% of total sample of obese women and 19.2% of the subgroup with depression (NS; P value NR) |

| Ertel[37] Prospective, cohort | EPDS ≥ 15 | Early pregnancy (< 20 wk) | n = 934 | No significant association between depressive symptoms in early pregnancy and GDM measures at mid-pregnancy [adjusted OR (95%CI): for abnormal glucose tolerance associated with depression: 1.34 (0.81-2.23); for impaired glucose tolerance associated with depression: 1.53 (0.73-3.22)] |

| Huang[38] Prospective, cohort | EPDS ≥ 13 | Mid-pregnancy (median 27.9 wk) and 6 mo (median 6.5 mo) after delivery | Prenatal, n = 2112 Postpartum, n = 1686 | Prevalence of GDM was 8% among women with prenatal depression, 6% among women without prenatal depression, 7% among women with postpartum depression, and 5% among women without postpartum depression Compared with women with normal glucose tolerance, the odds of prenatal depression were significantly higher in women with isolated hyperglycemia [adjusted OR (95%CI): 1.80 (1.08-3.00)], but not in women with impaired glucose tolerance [1.43 (0.59-3.46)] or GDM [1.45 (0.72-2.91)] There was a 25% higher odds of prenatal depression per SD increase (27 mg/dL) in glucose levels [OR (95%CI): 1.25 (1.07-1.48)] Pregnancy hyperglycemia was not associated with significantly higher odds of postpartum depression |

| Jovanovic[39] Retrospective, claims database | ICD-9 codes 311, 296.2, 296.3, 300.4, 301.12, 309.1 | Not specified, but data spanned from 21 mo before to 3 mo after delivery | n = 839792 GDM, n = 52848 No DM, n = 773751 | Prevalence of depression among women with GDM was 5.3% Relative risk (95%CI): of depression in women with GDM vs women with no DM was 1.17 (1.12-1.21) Prevalence of concurrent GDM and depression was 0.4% |

| Katon 2011[41] Cross-sectional analysis of prospective cohort | PHQ-9 | 3rd trimester | n = 2398 GDM, n = 425; No DM, n = 1747 | Prevalence (95%CI): of probable major depression among women with GDM was 4.5% (2.5%-6.4%) by PHQ-9 score, 5.7% (3.5%-7.9%) by antidepressant use, and 8.7% (6.0%-11.4%) by either PHQ-9 or antidepressant use, compared with the prevalence among women without DM [PHQ-9: 4.1% (3.2%-5.1%); antidepressants: 6.2% (5.1%-7.3%); PHQ-9 and antidepressants: 9.6% (8.2%-11.0%)] After adjusting for demographic characteristics, chronic medical conditions, and pregnancy variables, GDM was not associated with major [OR (95%CI): 0.90 (0.61-1.32)] or any [OR (95%CI): 0.95 (0.68-1.33)] antenatal depression |

| Katon 2014 (VA)[40] Retrospective, VA database | ICD-9 codes 296.2-296.39 | Up to date of delivery | n = 2288 GDM, n = 118 No GDM or hypertensive disorder, n = 1966 | Prevalence of depression was 9.3% in women with GDM and 8.8% in women without DM (no statistical analysis) |

| Katon 2014 (PPD)[42] Retrospective, hospital database | PHQ-9 | 2nd or 3rd trimester and 6 wk after delivery | n = 1423 | Prevalence of GDM did not differ between women with postpartum depression (19.3%) and women without postpartum depression (20.7%) (P = 0.89) GDM was not a risk factor for postpartum depression [OR (95%CI): 0.68 (0.40-1.13), P = 0.13] Prevalence of concurrent GDM and depression was 1.12% |

| Keskin[43] Prospective, cohort | BDI ≥ 17 | 24-28 wk gestation | n = 89 GDM, n = 44 No GDM, n = 45 | Prevalence of depression did not differ between women with GDM (80%) and women without GDM (83%) (P = 0.4) |

| Kim[44] Prospective, longitudinal | CES-D (cut-off NR) | Week 12-20 of gestation and 8-12 wk after delivery | n = 1445 GDM, n = 64; No GDM, n = 1233 | No difference in the proportion of women with depressive symptoms in the GDM (14.1%) vs no GDM (13.5%) group (P > 0.05) After adjustment, GDM was not associated with an increase in depressive symptoms between pregnancy and postpartum [adjusted OR (95%CI): 1.22 (0.54-2.77)] Calculated prevalence of both GDM and depression = 0.62% |

| Ko[45] (Korean) Prospective, cohort | Postpartum depression model (dissertation by JI Bae, Ewha Womans University) | Weeks 24 and 28 of gestation | n = 68 Coaching program group, n = 34 Control group, n = 34 | Women with GDM who participated in a 4-wk educational coaching program had a greater decrease in depression scores [mean (SD) change from baseline: -3.77 (6.50)] than women with GDM who did not participate in the program [mean (SD) change from baseline: 1.23 (6.76)] (P = 0.043) |

| Kozhimannil[46] Retrospective, cohort | ICD9 codes 296.2, 296.3, 300.4, 301.12, 309.1, and 311 | During the 6 mo before and up to 1 yr after delivery | n = 11024 With GDM, n = 346 (taking insulin, n = 163); No DM, n = 10367 | Prevalence of depression in women with GDM taking insulin was 16.0% vs 13.7% among women with GDM not taking insulin (P value not reported) Relative to women without diabetes, risk of depression was higher in both women with GDM taking insulin [adjusted OR (95%CI): 1.85 (1.19-2.87)] and in women with GDM not taking insulin [adjusted OR (95%CI): 1.69 (1.09-2.62)] |

| Levy-Shiff[66] Prospective | BDI | 2nd trimester | n = 153 GDM, n = 51 No DM, n = 49 | No significant difference in depression during 2nd trimester between GDM [mean (SD) BDI score 6.70 (4.46)] and controls [6.59 (5.88), P≥ 0.05] For sample as a whole, higher levels of cognitive assessment of pregnancy as a challenge was associated with lower depression (P < 0.05) |

| Liu[47] Prospective | Survey asking if diagnosed or discussed with HCP | Postpartum (mean 9.7 mo) | n = 3748 White, n = 1043 Asian/Pacific Islander, n = 425 Hispanic, n = 1253 Black, n = 1027 | Prevalence of GDM was 7.6% in white (P < 0.05 vs all other ethnic groups), 14.9% in Asian/Pacific Islander (P < 0.05 vs other ethnic groups), 10.1% in Hispanic (P < 0.05 vs white and Asian/Pacific Islander groups), and 10.1% in black (P < 0.05 vs white and Asian/Pacific Islander groups) populations Prevalence of pre-existing depression was 2.8% in white (P < 0.05 vs all other ethnic groups), 12.4% in Asian/Pacific Islander (P < 0.05 vs all other ethnic groups), 7.6% in Hispanic (P < 0.05 vs all other ethnic groups), and 5.5% in black (P < 0.05 vs all other ethnic groups) populations No association between GDM and PPD; African Americans with GDM had decreased likelihood of PPD compared with those without GDM [OR (95%CI): 0.1 (0.0-0.5)] Weighted percentage of women with PPD with or without GDM was 10% vs 7.5% in white women (P < 0.05), 18.6% vs 14.4% in Asian/Pacific Islander (P≥ 0.1), 13.8% vs 9.8% in Hispanic (P≥ 0.1), and 1.1% vs 10.4% in black women (P≥ 0.1) |

| Manoudi[48] Prospective, cross-sectional | MINI; HAM-D | NR | n = 187 GDM 2.7% | Proportion of patients with major depressive episode who also had GDM was 2.6% (same as overall population, which was 2.7%) |

| Mautner[49] Prospective | EPDS | 24th-37th week of gestation; 2-5 d postpartum; 3-4 mo postpartum | n = 40 GDM, n = 11 No GDM, n = 29 | Mean (SD) EPDS scores in late pregnancy [7.55 (5.48)], immediately postpartum [7.00 (3.74)], and 3-4 mo postpartum [6.36 (5.63)] were not different in women with GDM compared with women without pregnancy complications [mean (SD) EPDS scores 6.41 (4.37), 4.69 (4.43), and 5.48 (4.88) in late pregnancy, immediately postpartum, and 3-4 mo postpartum, respectively] (P≥ 0.05) |

| Mei-Dan[50] Retrospective, health administration database | ICD-9, ICD-10CA, and/or DSM-IV (ICD codes NR) | Within 5 yr before pregnancy | n = 437941 With pre-pregnancy depression, n = 3724 No known mental illness, n = 432358 | Prevalence of GDM during the index pregnancy was 3.4% in women with pre-pregnancy depression and 4.7% in women with no known mental illness (no statistical analysis) Prevalence of GDM and pre-pregnancy depression was 0.029% |

| Natasha[51] Prospective, case-control | MADRS ≥ 13 | Approx. 25 wk gestation | n = 748 GDM, n = 382 No GDM, n = 366 | Prevalence of depression was higher in women with GDM (25.92%) than in women without GDM (10.38%) (P value NR) There were significant associations between depression and current GDM (P < 0.001) and between depression and a history of GDM (P < 0.018) Mean (variance) MADRS scores were significantly higher in women with GDM [8.33 (7.23)] than women without GDM [4.42 (5.89)] (P value NR) Relative to women without GDM, women with GDM were more likely to have mild (MADRS score 13-19; adjusted OR: 3.07 or 4.06)3 or moderate (MADRS score 20-34; adjusted OR: 3.94) depression (P < 0.001) |

| Nicklas[52] Baseline description of RCT cohort | EPDS > 9 | Mean (SD) 7.0 (1.7) wk postpartum (range, 4-15 wk) | n = 71 | 24 (34%) women with GDM had EPDS > 9 at postpartum visit [mean (SD) score 11.4 (2.2)]; cesarean delivery (P = 0.005) and greater gestational weight gain (P = 0.035), but not history of depression (P = 0.97), were associated with PPD |

| O'Brien[53] Retrospective, records review | EPDS ≥ 10 | Mean (SD) 13.6 (8.2) wk gestation | n = 362 With depression, n = 256 Without depression, n = 106 | No difference in prevalence of GDM between women with EPDS < 10 (14.6%) and those with EPDS ≥ 10 (15.0%) (P≥ 0.05) |

| Ragland[54] Prospective, cross-sectional | BDI > 13 | During pregnancy | n = 50 GDM, n = 22 | Mean BDI score among women with GDM was 13.7 9 (41%) women with GDM had BDI > 13 |

| 4Räisänen 2013[56] Retrospective, registry review | ICD10 codes F31.3, F31.5, F32-34 | Up to 6 wk postpartum or a history of depression | n = 511422 | Prevalence of GDM: 11.2% of women without any depression (n = 492103), 13.8% of women with history of depression but not PPD (n = 17881), 17.4% of women with PPD but no history of depression (n = 431), and 17.6% of women with both history of depression and PPD (n = 1007) (P ≤ 0.001) Among women with history of depression, increased prevalence of PPD was associated with GDM [OR (95%CI): = 1.62 (1.23-2.14)] |

| 4Räisänen 2014[55] Retrospective, registry review | ICD10 codes F31.3, F31.5, F32-34 | Up to hospital discharge after delivery | n = 511938 | Prevalence of GDM: 11.2% of women without any depression (n = 493037), 13.4% of women with history of depression but not during pregnancy (n = 14781), 14.5% of women with depression during pregnancy but no history of depression (n = 2189), and 17.6% of women with both depression during pregnancy and history of depression (n = 1931) (P ≤ 0.001) An increased prevalence of depression during pregnancy was associated with GDM [adjusted OR (95%CI): 1.29 (1.11-1.50)] |

| Rumbold[57] Prospective | EPDS ≥ 12 | Late pregnancy (for GDM) | n = 212 GDM (or glucose intolerance of pregnancy), n = 25 Negative OGCT, n = 95 Positive OGCT/negative OGTT, n = 29 | No difference in proportion of women with EPDS score ≥ 12 in the GDM group (19%) compared with other groups (P≥ 0.05) |

| Silveira[58] Prospective, cohort | EPDS ≥ 13 | Early (mean 12.4 wk gestation) and mid (mean 21.3 wk) pregnancy | n = 1115 GDM, n = 52 No glucose abnormality, n = 953 | Prevalence of GDM did not differ between women with at least minor depression (EPDS ≥ 13) and women without depression (4.6% vs 5.6%) (P = 0.58) Prevalence of GDM did not differ between women with probably major depression (EPDS ≥ 15) and women without major depression (4.1% vs 5.6%) (P = 0.51) |

| Singh[59] Retrospective | BDI ≥ 10; self-reported medical history | During pregnancy | n = 152 History of depression, n = 39 No history of depression, n = 113 | Of 39 women with history of depression, 15 (38%) had GDM Of 113 women with no history of depression, 67 (59%) had GDM (P value not reported) |

| Sit[60] Prospective | DSM-IV (SCID) | Past or current diagnosis | n = 186 Past MDD, n = 41 Current MDD, n = 39 Bipolar disorder, n = 45 No psychiatric disorder, n = 61 | Mean (SD) glucose concentration after OGCT was 100 (25.0) mg/dL and did not differ among groups (P = 0.564) Rate of abnormal OGCT was 7% (13 of 186) and did not differ among the groups (P = 1.000) Only 3 women with abnormal OGCT were confirmed as having GDM (group not specified) |

| Song[61] (Chinese) Prospective | Self-rating Depression Scale ≥ 41 | During pregnancy | n = 104 GDM, n = 50 No GDM, n = 54 | Incidence of depression was 22% in women with GDM, significantly higher than in women without GDM (7.4%) (P < 0.05) Among women with GDM, mean (SD) insulin concentration 1 h after OGTT was significantly lower in women with depression [58.3 (32.4) mIU/mL, n = 11] than in those without depression [102.1 (65.2) mIU/mL, n = 39] (P < 0.05) |

| Sundaram[62] Prospective, exploratory | Survey of PPD diagnosis; survey of symptoms based on PHQ-2 | Postpartum | Up to 61733 pregnancies | In analysis of data from 22 states, GDM was not a significant predictor of PPD symptoms [OR (95%CI): 1.13 (0.93-1.30), n = 45642, P = 0.14) or diagnosis [OR (95%CI): 0.96 (0.64-1.52), n = 5919, P = 0.89) |

| Walmer[63] Retrospective, electronic medical records | ICD-9 codes 296.2, 296.3, 309.0, 309.1, 311, 300.4 | Postpartum | n = 18888 pregnancies (14988 women) GDM, n = 696 pregnancies (659 women) | After adjusting for age, pre-eclampsia, and preterm birth, GDM was significantly associated with increased risk of PPD [adjusted OR (95%CI): 1.46 (1.16-1.83), P = 0.001]; however, the association was not significant after adjusting for other clinical and demographic characteristics [adjusted OR (95%CI): 1.29 (0.98-1.70), P = 0.064] In subanalyses of ethnic/racial groups, GDM was significantly associated with PPD in black and white women, but not Hispanic women, after adjusting for age, pre-eclampsia, and preterm birth; the associations were not significant after full adjustment GDM was significantly predictive of mental health disorder (including depression, anxiety, and others) within 3 mo postpartum [adjusted OR (95%CI): 1.38 (1.04-1.85), P = 0.028] |

| Whiteman[64] Retrospective, maternal and infant database | ICD-9-CM codes 293.83, 296.2, 296.3, 300.4, 301.12, 309.0, 309.1, 311 | Up to hospital discharge after delivery | n = 1057647 | GDM was significantly associated with increased risk of depression [adjusted OR (95%CI): 1.44 (1.26-1.65)] (P value NR) Obesity was also associated with increased risk of depression, but there was no significant, additive interaction between GDM and obesity |

| First authorstudy design | Definition/measures of depression | Timing of depression measures | Overall nSubgroups, n | Main outcomes/findings |

| Berger[25] Retrospective | EPDS ≥ 13 or did not answer “No” to self-harm question | Within 4 d after delivery | Unselected, n = 322 History of mental illness, n = 215 | Prevalence of pre-existing DM did not differ between women with or without postpartum depression in either the unselected group or the group with history of mental illness Of 5 women with pre-existing DM, none had depression |

| Callesen[30] Prospective, cohort | HADS ≥ 8 | 8 wk gestation | n = 148 Type 1, n = 118 Type 2, n = 30 | Women with DM and depression were more likely to have preterm delivery (54% vs 16%, P = 0.003) and less likely to be nulliparous (23% vs 54%, P = 0.03) than women with DM without depression |

| Dalfra[34] Prospective | CES-D ≥ 16 | 3rd trimester and 8 wk after delivery | n = 245 Type 1, n = 30; No DM, n = 39 | Mean (SD) CES-D scores at 3rd trimester were 19.1 (9.6) among women with Type 1 DM and 18.0 (8.7) among women without DM (P = 0.67) The severity of depressive symptoms increased from the 3rd trimester to after delivery in women with Type 1 DM [estimated mean difference in CES-D score (95%CI): 6.6 (2.9-10.2)], but decreased in women without DM [2.7 (-5.9-0.5), P < 0.0001 between groups] |

| Jovanovic[39] Retrospective, claims database | ICD-9 codes 311, 296.2, 296.3, 300.4, 301.12, 309.1 | During pregnancy and/or within 3 mo after delivery | n = 839792 Type 1, n = 1125 Type 2, n = 10136 No DM, n = 773751 | Prevalence of depression was 5.2% and 8.3% among women with type 1 and type 2 DM, respectively Prevalence of concurrent type 1 DM and depression was 0.006% Prevalence of concurrent type 2 DM and depression was 0.086% Relative risk (95%CI): of depression in women with type 1 DM vs women with no DM was 1.16 (0.86-1.56) Relative risk (95%CI): of depression in women with type 2 DM vs women with no DM was 1.84 (1.70-2.00) |

| Katon 2011[41] Cross-sectional analysis of prospective cohort | PHQ-9 | 3rd trimester | n = 2398 Pre-existing DM (type NR), n = 226; No DM, n = 1747 | Prevalence (95%CI): of probable major depression among women with pre-existing DM was 5.8% (2.7%-8.8%) by PHQ-9 score, 8.9% (5.1%-12.6%) by antidepressant use, and 13.3% (8.8%-17.7%) by either PHQ-9 or antidepressant use, compared with the prevalence among women without DM [PHQ-9: 4.1% (3.2%-5.1%); antidepressants: 6.2% (5.1%-7.3%); PHQ-9 and antidepressants: 9.6% (8.2%-11.0%)] After adjusting for demographic characteristics, chronic medical conditions, and pregnancy variables, pre-existing DM was not associated with major or any antenatal depression (P value not reported) |

| Katon 2014 (PPD)[42] Retrospective, hospital database | PHQ-9 | 2nd or 3rd trimester and 6 wk after delivery | n = 1423 | Prevalence of pre-existing DM was higher in women with PPD (14.5%) than in women without PPD (6.9%) (P = 0.02) Of 104 women with pre-existing DM, 12 (11.5%) had PPD Pre-existing DM was a risk factor for postpartum depression [OR (95%CI): 1.98 (1.12-3.52)] (P = 0.02) Prevalence of concurrent pre-existing DM and depression was 0.84% |

| Kozhimannil[46] Retrospective cohort | ICD9 codes 296.2, 296.3, 300.4, 301.12, 309.1, and 311 | During the 6 mo before and up to 1 yr after delivery | n = 11024 With pre-existing DM (type NR), n = 311 (taking insulin, n = 57); no DM, n = 10367 | Prevalence of depression in women with pre-existing DM taking insulin was 14.0% vs 16.1% among women with pre-existing DM not taking insulin (P value not reported) |

| Levy-Shiff[66] Prospective | BDI | 2nd trimester | n = 153 Pre-existing DM, n = 53 (type NR) No DM, n = 49 | No significant difference in depression during 2nd trimester between pre-existing DM [mean (SD) BDI score 6.17 (5.16)] and controls [6.59 (5.88)] (P≥ 0.05) For sample as a whole, higher levels of cognitive assessment of pregnancy as a challenge was associated with lower depression (P < 0.05) Among women with pre-existing DM, higher levels of medical support were associated with lower levels of depression (P < 0.01) |

| Mei-Dan[50] Retrospective, health administration database | ICD-9, ICD-10CA, and/or DSM-IV (ICD codes NR) | Within 5 yr before pregnancy | n = 437941 With pre-pregnancy depression, n = 3724 No known mental illness, n = 432358 | Prevalence of DM (type NR) within 1 year before the index pregnancy was significantly higher in women with pre-pregnancy depression (3.4%) than in women with no known mental illness (1.2%) (P value NR) Prevalence of pre-existing DM and pre-pregnancy depression was 0.029% |

| Moore[67] Prospective | Depression Adjective Checklist; Perceived Stress Scale | 3rd trimester | n = 131 Pre-existing insulin-dependent DM, n = 73 High risk of preterm birth, n = 48 Low risk of preterm birth, n = 25 | White women with DM who were tested at a private clinic had higher Depression Adjective Checklist and Perceived Stress Scale scores than any other group (variables of white vs black, private vs public medical centre, DM vs low or high risk of preterm birth) (P value not reported) |

| Ragland[54] Prospective, cross-sectional | BDI > 13 | During pregnancy | n = 50 Type 1 DM, n = 8 Type 2 DM, n = 20 | Mean BDI score was 10.0 among women with type 1 DM and 17.1 among women with type 2 DM No women with type 1 DM and 12 (60%) women with type 2 DM had BDI > 13 |

| 1Räisänen 2013[56] Retrospective, registry review | ICD10 codes F31.3, F31.5, F32-34 | Up to 6 wk postpartum or a history of depression | n = 511422 | Prevalence of pre-existing DM: 8.4% of women without any depression (n = 492103), 11.1% of women with history of depression but not PPD (n = 17881), 14.6% of women with PPD but no history of depression (n = 431), and 13.3% of women with both history of depression and PPD (n = 1007) (P ≤ 0.001) |

| 1Räisänen 2014[55] Retrospective, registry review | ICD10 codes F31.3, F31.5, F32-34 | At hospital discharge after delivery | n = 511938 | Prevalence of pre-existing DM (type NR): 8.4% of women without any depression (n = 493037), 10.9% of women with history of depression but not during pregnancy (n = 14781), 11.6% of women with depression during pregnancy but no history of depression (n = 2189), and 13.6% of women with both depression during pregnancy and history of depression (n = 1931) (P ≤ 0.001) Depression during pregnancy was not associated with pre-existing DM [adjusted OR (95%CI): = 1.10 (0.93-1.31)] |

| Singh[59] Retrospective | BDI ≥ 10; self-reported medical history | During pregnancy | n = 152 History of depression, n = 39 No history of depression, n = 113 | Type 2 DM was significantly more common in women with history of depression than in women with no history of depression (P < 0.05) Of 39 women with history of depression, 5 (13%) had type 1 DM, and 19 (49%) had type 2 DM Of 113 women with no history of depression, 18 (16%) had type 1 DM, and 28 (25%) had type 2 DM |

| Sundaram[62] Prospective, exploratory | Survey of PPD diagnosis; survey of symptoms based on PHQ-2 | Postpartum | Up to 61733 pregnancies | In analysis of data from 22 states, pre-existing DM was not a significant predictor of PPD symptoms [OR (95%CI): 1.16 (0.78-1.59), n = 45669, P = 0.39) or diagnosis [OR (95%CI): 1.31 (0.45-3.06), n = 5924, P = 0.56)] In analysis of data from 2 states that included both PPD symptoms and diagnosis on the survey, pre-existing DM was a significant predictor of PPD diagnosis [OR (95%CI): 5.65 (1.72-15.37), n = 2136, P < 0.01)] |

| First authorstudy design | Definition/measures of depression | Timing of depression measures | Overall nSubgroups, n | Main outcomes/findings |

| Ahmed[21] Prospective, cross-sectional | EPDS ≥ 10 | 6-8 wk postpartum | n = 1000 With DM (type NR), n = 31 No DM, n = 969 | The proportion of women with DM who had PPD (51.6%) was significantly higher than the proportion of women without DM who had PPD (27.7%) (P = 0.004) Calculated prevalence of women with both DM and PPD was 1.6% (16 of 1000) |

| Bansil[22] Retrospective | ICD9 codes 296.2, 296.3, 300.4, 311, 298.0, 309.0, 309.1 | At the time of delivery | n = 32156438 With depression, n = 244939; With DM (type 1, type 2, or GDM), n = 1536514 With DM and depression, n = 18245 | Rate of concurrent DM at the time of delivery higher in women with depression (74.5 per 1000 deliveries) vs women without depression (47.6 per 1000 deliveries; OR (95%CI): 1.52 (1.47-1.58)] Calculated prevalence of DM and depression = 0.06% (18245 of 32156438 deliveries) |

| Benute[24] Prospective | PRIME-MD | During prenatal outpatient visits/hospital-isation | n = 326 With DM, n = 84 With MDD, n = 29 | Prevalence of DM in women with MDD was 7.1% Calculated prevalence of DM and MDD = 0.61% (7.1% of 29 = 2; 2/326 = 0.61%) |

| Berger[25] Retrospective | EPDS ≥ 13 or did not answer “No” to self-harm question | Within 4 d after delivery | Unselected, n = 322 History of mental illness, n = 215 | Prevalence of any DM did not differ between women with or without postpartum depression in either the unselected group or the group with history of mental illness |

| Chen[32] Retrospective | ICD9 codes 296.2, 296.3, 300.4, and 311 | History of depression within 2 years before delivery | n = 5283 With DM (type NR), n = 319 | Calculated prevalence of DM among women with depression was 6.0% |

| Kozhimannil[46] Retrospective cohort | ICD9 codes 296.2, 296.3, 300.4, 301.12, 309.1, and 311 | During the 6 mo before and up to 1 year after delivery | n = 11024 With DM (pre-existing or GDM), n = 657; | Overall calculated prevalence of women with both DM (any type) and depression was 1.1% Prevalence of depression among women with any DM was 15.2% vs 8.5% among women without DM (P value not reported) |

| Ragland[54] Prospective, cross-sectional | BDI > 13 | During pregnancy | No DM, n = 10367 n = 50 Type 1 DM, n = 8 Type 2 DM, n = 20 GDM, n = 22 | Women with any DM had an increased odds of experiencing depression during or after pregnancy [OR (95%CI): 1.85 (1.45-2.36)] vs women without DM Women with any DM and no prenatal depression (9.6%) had increased odds of experiencing PPD or taking an antidepressant in the year after delivery [OR (95%CI): 1.69 (1.27-2.23)] vs women without DM Mean (SD) BDI score was 14.1 (9.9), range 3-43 Number (%) women with DM and severe (BDI ≥ 29), moderate (BDI 20-28), mild (BDI 14-19), and minimal (BDI 0-13) depression was 5 (10%), 8 (16%), 8 (16%), and 29 (58%) 42% of women with DM had BDI scores > 13, indicating clinical depression Among patients with clinical depression, only 19% were receiving treatment for depression Number of pregnancies showed a positive correlation with BDI score (P = 0.0078) Least mean squares of HbA1c level was higher, but not significantly, in women with depression [7.3% (56 mmol/mol)] than in those without [6.9% (52 mmol/mol)] (P≥ 0.05) |

| Räisänen 2013[56] Retrospective, registry review | ICD10 codes F31.3, F31.5, and F32-34 | Up to 6 wk postpartum or a history of depression | n = 511422 | Calculated prevalence of DM (any type) and depression in pregnant women = 0.06% |

| Singh[59] Retrospective | BDI ≥ 10; self-reported medical history | During pregnancy | n = 152 History of depression, n = 39 No history of depression, n = 113 | Current BDI scores were higher in women with DM and history of depression [mean (SD) 17.2 (11.5)] than in women with DM and no history of depression [7.8 (7.4), P < 0.0001] Percentage of women with BDI ≥ 10 significantly greater in women with DM and history of depression (72%) than in women with DM and no history of depression (28%, P < 0.0001) |

| York[65] Prospective | Multiple Adjective Check List | 36 wk gestation, and 2 d, 1 wk, 4 wk, and 8 wk postpartum | n = 36 Pre-existing DM, n = 6 GDM, n = 30 | Most women did not report high levels of depression Among all women with DM, depression scores decreased significantly (P < 0.001) over time [mean (SD) scores of 9.2 (6.6), 10.1 (8.3), 6.7 (8.2), 5.6 (7.0), and 3.8 (4.2) at 36 wk gestation, 2 d postpartum, 1 wk postpartum, 4 wk postpartum, and 8 wk postpartum, respectively] There were no differences between women with GDM and women with pre-existing DM in depression scores during pregnancy (P = 0.17) or postpartum (P value not reported) |

A total of 28 studies included only women with GDM[20,23,26-29,31,33,35-38,40,43-45,47-49,51-53,57,58,60,61,63,64], 14 included women with either GDM or pre-existing diabetes (although the type was not always reported)[22,25,39,41,42,46,50,54-56,59,62,65,66], one included women with either GDM or type 1 diabetes[34], one included only women with type 1 diabetes[67], one included only women with pre-existing diabetes (type not reported)[30] and three did not report the type of diabetes[21,24,32] (Tables 1-3, Supplementary Table 1). Sample sizes ranged from 36[65] to more than 32 million in a retrospective analysis of a nationwide hospital database[22] (Tables 1-3, Supplementary Table 1).

Overall study quality was poor. Most studies were prospective observational studies (Tables 1-3, Supplementary Table 1), which were subject to limitations such as small sample size and selection bias. Further, most studies defined depression using measures of depressive symptoms rather than more rigorous clinical diagnosis tools. Among those that did use clinical diagnosis tools, most were retrospective, including six national, state/provincial, or veterans’ health database studies[32,40,50,55,56,64], two claims registry studies[39,46], and three hospital records review studies[22,28,63]. Although these studies were large, their retrospective nature was an inherent limitation. Unlike the health database studies, the claims registry and hospital records review studies were subject to potential selection bias. Importantly, the primary objective of many of the studies was not relevant to this systematic review (Supplementary Table 1), and the results we collected were often secondary or incidental findings.

The small number of RCTs identified may reflect ethical concerns regarding enrolment of pregnant women in interventional studies. The one completed RCT was the highest quality study included in this review[33], having appropriate allocation sequence generation and concealment, as well as attempts to maintain blinding; however, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) data at 3 mo postpartum were available for fewer than 60% of patients, indicating potential attrition bias.

The definition of depression varied widely across the studies (Tables 1-3), and only a quarter of the studies (almost all retrospective) classified participants as having depression based on a formal clinical diagnosis. Only one prospective study defined depression using the Structural Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)[60]. This study examined responses to oral glucose challenge tests among women with or without current or past diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder, including major depressive disorder. However, only 3 of 186 women were subsequently diagnosed with GDM, and the publication did not report whether these women had depression, another psychiatric disorder, or no psychiatric disorder. Eleven retrospective studies used International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes[68] in medical records to classify participants as having current or a history of depression[22,28,32,39,40,46,50,55,56,63,64]. One of these retrospective studies also included diagnoses based on the DSM-IV[50]. One retrospective study[59] and one prospective study[62] relied on participant self-reporting of depression diagnosis. Aside from these studies, all other studies used measures of depressive symptoms, most commonly the EPDS; however, the cut-off score for clinically significant depression varied from 9 to 15. Other depressive symptom scales included the Beck Depression Inventory, the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale, the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, and the Patient Health Questionnaire.

In general, the large retrospective studies that used ICD codes reported a significant association between depression and DIP, especially GDM. Two claims registry studies (n = 11024[46]; n = 839792[39]) reported that women with DIP (except type 1 diabetes) were at increased risk of developing depression during or after pregnancy relative to pregnant women without diabetes [any DIP: OR (95%CI): 1.85 (1.45-2.36)[46]; GDM: Relative risk (95%CI): 1.17 (1.12-1.21)[39]; type 2 diabetes: Relative risk (95%CI): 1.84 (1.70-2.00)[39]; type 1 diabetes: Relative risk (95%CI): 1.16 (0.86-1.56)[39]]. Similarly, a maternal and infant database study (n = 1057647) reported that GDM was significantly associated with increased risk of depression at the time of hospital discharge after delivery [adjusted OR (95%CI): 1.44 (1.26-1.65)][64]. A hospital records review (n = 18192 pregnancies) reported that GDM was significantly associated with increased risk of postpartum depression after adjustment for age, pre-eclampsia, and preterm birth [OR (95%CI): 1.46 (1.16-1.83); P = 0.001], but not after adjustment for other clinical and socioeconomic factors [OR (95%CI): 1.29 (0.98-1.70); P = 0.064)[63]. Conversely, another hospital records review (n = 128295) reported that a history of depression was a risk factor for the development of GDM [OR (95%CI): 1.42 (1.26-1.60)][28]. A national health database study (n > 32 million) reported that women with depression at delivery were more likely to also have diabetes (type not specified) than women without depression [OR (95%CI): 1.52 (1.471.58)][22]. In another national health database study that examined the relationship between reproductive risk factors and postpartum depression (n = 511422), the prevalence of DIP (pre-existing or gestational) was greater among women with a history of depression or with postpartum depression than among those without any depression[56]. This study also reported that in women with a history of depression, the risk of postpartum depression is increased in those who also have GDM [OR (95%CI): 1.62 (1.23-2.14)]. A related study using the same database reported that an increased prevalence of depression during pregnancy was associated with GDM [adjusted OR (95%CI): 1.29 (1.11-1.50)], but not with pre-existing diabetes [adjusted OR (95%CI): 1.10 (0.93-1.31)][55]. The remaining health database studies that used ICD codes only reported prevalence data[32,40,50].

The timing of depression assessment also varied (Tables 1-3). There were 22 studies that measured depression only during pregnancy[22,24,26,30,31,36,37,40,41,43,45,51,53-55,57-59,61,64,66,67]. Conversely, 11 studies focussed on postpartum depression, most commonly measured within the first 3 mo[20,21,23,25,27,29,33,47,52,62,63]. There were nine studies that measured depression during both pregnancy and postpartum[34,35,38,39,42,44,46,49,65] and five studies that classified participants based on a history of pre-pregnancy depression[28,32,50,56,60].

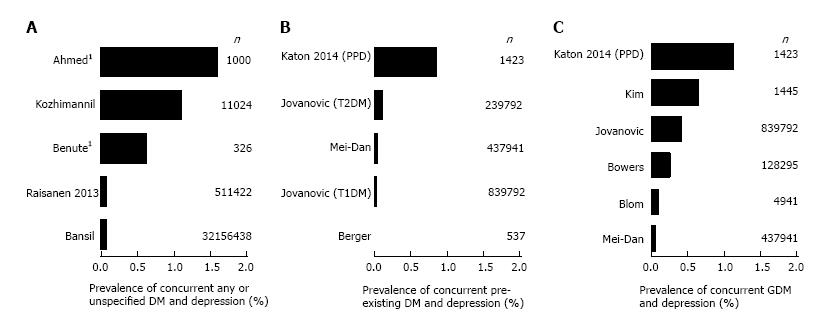

The prevalence of concurrent DIP and depression in a general population sample of pregnant or postpartum women was reported or could be calculated from data in 12 retrospective or cross-sectional studies[21,22,24,25,27,28,39,42,44,46,50,56] and ranged from 0% to 1.6% (median 0.61%) (Figure 2). The prevalence of depression during or after pregnancy concurrent with any or unspecified diabetes ranged from 0.06% to 1.6% (5 studies; median 0.61%) (Figure 2A). The prevalence of concurrent pre-existing diabetes and depression during or after pregnancy ranged from 0.006% (type 1 diabetes only) to 1.1% (4 studies, median 0.03%) (Figure 2B). The prevalence of concurrent GDM and depression during or after pregnancy ranged from 0.029% to 1.12% (6 studies, median 0.32%) (Figure 2C).

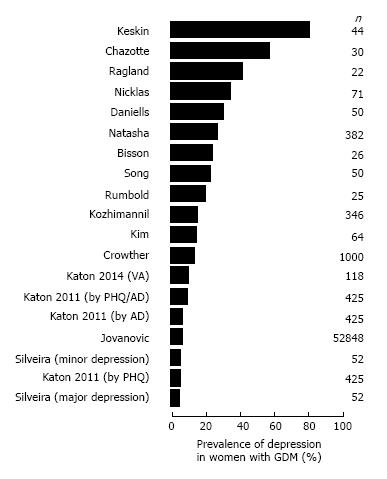

Among women with GDM (Table 1, Figure 3), the reported prevalence of depression during or after pregnancy ranged widely, from 4.1% to 80% (16 studies[26,31,33,35,39-41,43,44,46,51,52,54,57,58,61], median 14.7%). Heterogeneity in sample size, the definition of depression, and the timing of its assessment is likely to have contributed to this wide range of prevalence rates.

The prevalence of GDM among women with a history of depression, reported in seven studies[23,27,28,48,50,55,56], ranged from 1.0%[27] to 17.6% (women with both history of depression and postpartum depression[55,56]) (Table 1).

Among women with pre-existing diabetes (Table 2), the prevalence of depression during or after pregnancy ranged from 0% to 60% (6 studies, median 8.3%), similar to the broad range reported for women with GDM. The prevalence of depression during or after pregnancy in women with pre-existing diabetes was 0% (in a small sample of five women with pre-existing diabetes)[25], 0% (in a small sample of eight women with type 1 diabetes)[54], 5.2% (type 1 diabetes)[39], 5.8%[41], 8.3% (type 2 diabetes)[39], 11.5%[42], 14.0% (women taking insulin)[46], 16.1% (women not taking insulin)[46], and 60% (women with type 2 diabetes)[54].

Many of the studies examined whether DIP was a risk factor for depression during or after pregnancy, or compared the prevalence of depression between women with DIP and pregnant women without diabetes. Overall, there was no consensus regarding whether women with DIP were more likely to have depression than pregnant women without diabetes.

In 11 studies[20,25,26,29,35,39,51,55,56,61,64], women with GDM had a significantly greater prevalence or risk of depression during or after pregnancy than pregnant women without diabetes (Table 1). In two of these studies, a significant effect of GDM was observed only for one subgroup of women (Qatari women, but not other Arab women[29]; women with a history of depression, but not women without a history of depression[56]). In one study[35], the prevalence of depression among women with GDM was significantly greater than pregnant women without diabetes at 30 wk gestation, but not at 36 wk gestation or postpartum. In contrast, 16 studies reported no significant effect of GDM on the prevalence or risk of depression[23,27,31,34,38,41-44,47,49,57,58,62,63,66].

Four studies reported no significant difference in depression between pregnant women with pre-existing diabetes and those without diabetes[25,41,55,66] (Table 2). One exploratory study was inconclusive, reporting that pre-existing diabetes was a significant predictor of postpartum depression diagnosis in a subset of data from two states of the United States, but not in the nationwide analysis set[62]. In one retrospective study, pre-existing type 2 diabetes, but not type 1 diabetes, was associated with an increased risk of depression during or after pregnancy[39]. In another retrospective study, pre-existing diabetes was identified as a risk factor for postpartum depression[42].

Two studies reported a greater prevalence[21] or risk (OR)[46] of depression among women with any type of DIP compared with pregnant women without diabetes (Table 3). One study reported a significant increase in the severity of depressive symptoms between the third trimester and postpartum among women with GDM or type 1 diabetes, but not among pregnant women without diabetes[34]. Another study reported no difference in the prevalence of any diabetes between women with postpartum depression and those without postpartum depression[25].

Several studies examined whether depression was a risk factor for the development of GDM, but again, there was no consensus (Table 1). Two studies of the same national database reported a greater prevalence[55,56] and one study reported a greater risk (OR[28]) of GDM among women with a pre-pregnancy history of depression. In contrast, two studies reported no difference in the prevalence of GDM (or abnormal glucose levels) among women with depression early in pregnancy compared with women without depression[37,53], and a third study reported similar prevalence rates of GDM in women with and without pre-pregnancy depression[50].

Our literature search did not identify any specific guidelines on the treatment or management of women with both DIP and depression during or after pregnancy. Very few studies reported on the effects of treatment of either diabetes or depression on outcomes. In the completed RCT[33], a significantly lower proportion of women with GDM who received dietary advice, performed blood glucose monitoring, and were treated with insulin therapy as needed had postpartum depression compared with women with GDM who received usual obstetric care (8% vs 17%; P = 0.001). In the prospective study by Dalfrà et al[34], mean depressive symptom scores during the third trimester did not differ between women with GDM who were managed with diet only and women with GDM who were treated with insulin (P = 0.58). In the retrospective study by Kozhimannil et al[46], the prevalence of depression during or after pregnancy among women with GDM who were treated with insulin was slightly higher than in women who were not treated with insulin (16.0% vs 13.7%; P value not reported). In the same study, the prevalence of depression among women with pre-existing diabetes was slightly lower in those who were treated with insulin than in those who were not (14.0% vs 16.1%; P value not reported). In the prospective study by Levy-Shiff et al[66], higher levels of patient-reported support from medical staff were associated with lower levels of depression in women with pre-existing diabetes (P < 0.01). Similarly, in the prospective study by Ko et al[45], women with GDM who participated in a 4-week educational coaching program had a greater decrease in depression scores than those who did not participate. In the prospective study by Ragland et al[54], only 19% of women with concurrent DIP (any type) and depression (Beck Depression Inventory score > 13) were receiving treatment for depression. In the same study, the HbA1c level was numerically higher, but not significantly higher, in women with both DIP and depression compared with pregnant women without depression [7.3% (56 mmol/mol) vs 6.9% (52 mmol/mol); P≥ 0.05].

This is the first systematic literature review assessing what is known about women who have both DIP and depression during pregnancy or postpartum. Despite the number of studies identified, there was no clear consensus on whether women with DIP are more likely to develop depression than pregnant women without diabetes, or whether women with depression were more likely to develop GDM. Heterogeneity in the definition of depression, the scales used to measure depressive symptoms, the timing of measures, and the types of diabetes examined, together with the poor quality and observational nature of most of the studies, are likely to have contributed to the lack of consensus. Further, the primary objective of many studies was not directly relevant to this review and the results we report were often secondary or incidental findings. Importantly, we did not identify any guidelines for the management of women with both DIP and depression. Given that 0.006% to 1.6% (median 0.61%) of pregnant women are reported to have both diabetes and depression, and that this prevalence is likely to rise, guidance on managing these women would be valuable to healthcare professionals.

Although many of the studies in this review examined the relationship between DIP and depression, there was no consensus on whether women with DIP are at greater risk of depression than pregnant women without diabetes. The reasons for the disparate results among the studies may in part be due to different definitions of depression and the timing of its measurement, as well as differences in study population, outcomes, and objectives. Only a quarter of the studies used a diagnosis of depression instead of symptoms, which may have made it more difficult to establish if there was a link. For example, in a meta-analysis of studies involving non-pregnant patients, diabetes was identified as a significant risk factor for depression as defined by diagnosis or prescription of antidepressants, but not when depression was defined by symptoms using questionnaires[9]. However, almost all the large, retrospective database studies that used ICD codes to define depression were suggestive of an increased prevalence or risk of depression among women with DIP, especially those with GDM[22,39,46,55,56,64].

Although the exact mechanisms that link diabetes and depression are not known, especially in pregnant or postpartum women, current hypotheses in non-pregnant patients focus on both psychological and biological factors[13]. For example, the higher prevalence of depression in patients with diabetes may be related to the burden of coping with a chronic disease[69]. Conversely, depression is often associated with lifestyle choices, such as poor diet and lack of exercise, which may increase the risk of developing type 2 diabetes. However, these behavioral factors do not account for all of the increased risk of diabetes in patients with depression[70,71]. Depression and diabetes may also share some biological pathologies, such as altered activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, sympathetic nervous system, and inflammatory processes[72]. Regardless of the underlying mechanisms, there is now considerable evidence that diabetes and depression are closely linked and that patients with either disease are at increased risk of developing the other[8-12]. Whether the same mechanisms are involved in linking depression with diabetes in pregnancy remains unclear, and studies designed to investigate these mechanisms are required.

Few studies examined the potential role of treatment or glycemic control on depression in women with DIP. Among these, the RCT by Crowther et al[33] reported that women with GDM who received active intervention (dietary advice, glucose monitoring, and insulin therapy, if needed) were significantly less likely to develop postpartum depression than women receiving routine obstetric care. Unfortunately, measures of glycemic control and their relationship to postpartum depression were not reported. A previous meta-analysis has indicated that depression among non-pregnant patients with diabetes was significantly associated with poorer glycemic control[73]. However, there is no similar evidence for a relationship between glycemic control and depression among pregnant women.

There was also no consensus among the few studies that examined whether pre-pregnancy depression increased the risk of GDM. Given that depression is linked to obesity and insulin resistance[13], women with depression who become pregnant should be carefully monitored for impaired glucose tolerance. In addition, certain antidepressant and centrally acting antipsychotic medications may increase the risk of type 2 diabetes[74]. This relationship is attributable to several mechanisms, both associated with and independent of weight gain[74], and a similar relationship may exist for GDM.

This review is strengthened by the systematic methods used to identify publications and by the absence of restrictions on publication date or language. In addition, the inclusion of studies involving all types of diabetes and definitions of depression increased the number of publications reviewed. However, the resulting heterogeneity, especially in the definition of depression, is likely to have contributed to the lack of consensus. Indeed, our original intent was to only include studies that used a formal clinical diagnosis of depression. However, preliminary searches revealed that few such studies exist and most of those that do are retrospective. For this reason, we expanded our inclusion criteria to also capture studies that used measures of depressive symptoms, allowing us to assess the wider body of evidence on this topic.

Our review is also limited by the observational nature of almost all the studies and because many of the studies were not designed to examine the relationship between depression and DIP. Observational studies are subject to a range of potential biases, including selection bias, information bias, recall bias, and attrition bias. In addition, many of the articles included in the review were poorly reported, making assessment of the true quality of individual studies difficult. Most studies did not report outcomes of specific interest to us, such as the effect of treatment for depression or diabetes on maternal outcomes, risk factors that contribute to co-occurrence of depression and DIP, and prevalence rates, many of which we calculated from reported data. However, RCTs involving pregnant women are uncommon because of ethical considerations, and observational studies may be the only way to examine the relationship between depression and DIP.

Importantly, we did not identify any specific guidelines for the management of women with both DIP and depression during or after pregnancy. Unfortunately, major clinical treatment guidelines for diabetes and depression do not address these patients. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) Standards of Medical Care recommend routine screening for depression in patients with diabetes, but any special care for pregnant women is not addressed[15]. Similarly, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Practice Bulletin on GDM does not address mental health issues[16]. Although the American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for major depressive disorder provides guidance for patients who also have diabetes or are pregnant, it does not provide guidance for women who have DIP[18]. However, limited management guidance for women with DIP and depression is provided by some country-specific guidelines (e.g., Germany[75] and India[76]). In addition, a consensus statement published by the ADA in 2008 recommends screening for depression before and during pregnancy in women with pre-existing diabetes[77]. Although the consensus statement indicates that the management plan should be adjusted in women with DIP and depression, the only recommendation provided is to use structured psychotherapy as first-line treatment for mild depression[77]. Given the expected increase in the number of women with DIP and depression, together with the particular challenges these women face in caring for themselves and their children, healthcare professionals need more specific guidance on management strategies for these patients. A collaborative care approach involving primary care physicians and specialists improves outcomes in non-pregnant patients with both diabetes and depression[78], and a similar model may be effective for the management of pregnant and postpartum women. Such guidance, however, should be based on sound research evidence, which, as our review demonstrates, is currently lacking. In agreement with the results of our systematic review, two narrative reviews[5,6] and a systematic review focussing on the transition to motherhood in women with type 1 diabetes[79] have recognized that rigorous research into DIP and depression (and other psychosocial issues) is much needed. In addition, greater awareness of depression is needed among clinicians who treat women with diabetes, which will allow for better planning and management of pregnancy.

In conclusion, this systematic review highlights the need for additional, high-quality research into the relationship between DIP and depression. Such research is needed to inform the development of evidence-based guidelines that will help clinicians care for women with both DIP and depression.

Medical writing assistance was provided by Rebecca Lew, PhD, CMPP and Serina Stretton, PhD, CMPP of ProScribe - Envision Pharma Group, and was funded by Eli Lilly Australia and New Zealand. ProScribe’s services complied with international guidelines for Good Publication Practice (GPP3).

Diabetes in pregnancy (DIP) has adverse effects on women and their children, as does depression during pregnancy or postpartum. Both DIP and depression are increasingly common, and it is likely that the number of women with both conditions is also growing. However, major diabetes and mental health guidelines do not provide adequate advice regarding care of patients with both DIP and depression.

At present, the prevalence of women with concurrent DIP and depression has not been established. In addition, recent evidence suggests a bidirectional relationship between diabetes and depression among non-pregnant patients, but it is not known if a similar link exists in pregnant or postpartum patients.

This is the first systematic literature review assessing what is known about women who have both DIP and depression during pregnancy or postpartum. Despite the number of studies identified (n = 48), there was no clear consensus on whether women with DIP are more likely to develop depression than pregnant women without diabetes, or whether women with depression were more likely to develop gestational diabetes. Importantly, they did not identify any guidelines for the management of women with both DIP and depression.

This systematic review highlights the need for additional, high-quality research into the relationship between DIP and depression. Such research is needed to inform the development of evidence-based guidelines that will help clinicians care for women with both DIP and depression.

Women with DIP include those who had pre-existing type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus before becoming pregnant and those who developed gestational diabetes mellitus during pregnancy. Gestational diabetes mellitus is characterized by elevated blood glucose levels that develop during mid-pregnancy and that usually resolve after childbirth.

This manuscript is a systematic review of the literature about the relationship between depression (postpartum depression in particular) and diabetes in pregnancy. The assessment of the articles indicated overall poor study quality as many studies were observational and often lacked stringent, objective criteria to support a diagnosis of clinical depression. The main conclusion of the authors is that high quality research with stringent criteria and assessable parameters is needed to establish specific guidelines for management of pregnant women with depression and diabetes.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Endocrinology and metabolism

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A, A, A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Gómez-Sáez J, Romani A, Roth A, Tarantino G S- Editor: Kong JX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas. 7th ed. Available from: http://www.idf.org/diabetesatlas. |

| 2. | Veeraswamy S, Vijayam B, Gupta VK, Kapur A. Gestational diabetes: the public health relevance and approach. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;97:350-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bardenheier BH, Imperatore G, Devlin HM, Kim SY, Cho P, Geiss LS. Trends in pre-pregnancy diabetes among deliveries in 19 U.S. states, 2000-2010. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48:154-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bardenheier BH, Imperatore G, Gilboa SM, Geiss LS, Saydah SH, Devlin HM, Kim SY, Gregg EW. Trends in Gestational Diabetes Among Hospital Deliveries in 19 U.S. States, 2000-2010. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49:12-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Byrn MA, Penckofer S. Antenatal depression and gestational diabetes: a review of maternal and fetal outcomes. Nurs Womens Health. 2013;17:22-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rasmussen-Torvik LJ, Harlow BL. The association between depression and diabetes in the perinatal period. Curr Diab Rep. 2010;10:217-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | DelRosario GA, Chang AC, Lee ED. Postpartum depression: symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment approaches. JAAPA. 2013;26:50-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nouwen A, Winkley K, Twisk J, Lloyd CE, Peyrot M, Ismail K, Pouwer F. Type 2 diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for the onset of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2010;53:2480-2486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 558] [Cited by in RCA: 508] [Article Influence: 33.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rotella F, Mannucci E. Diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for depression. A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;99:98-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Roy T, Lloyd CE. Epidemiology of depression and diabetes: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2012;142 Suppl:S8-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 881] [Cited by in RCA: 769] [Article Influence: 59.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Knol MJ, Twisk JW, Beekman AT, Heine RJ, Snoek FJ, Pouwer F. Depression as a risk factor for the onset of type 2 diabetes mellitus. A meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2006;49:837-845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 632] [Cited by in RCA: 617] [Article Influence: 32.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rotella F, Mannucci E. Depression as a risk factor for diabetes: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74:31-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 255] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Oladeji BD, Gureje O. The comorbidity between depression and diabetes. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2013;15:390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gonzalez JS, Peyrot M, McCarl LA, Collins EM, Serpa L, Mimiaga MJ, Safren SA. Depression and diabetes treatment nonadherence: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2398-2403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 627] [Cited by in RCA: 697] [Article Influence: 41.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Introduction. Diabetes Care. 2016;39 Suppl 1:S1-S2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Practice Bulletin No. 137: Gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:406-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 395] [Cited by in RCA: 459] [Article Influence: 38.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | NICE. NICE Clinical Guideline 3. Diabetes in pregnancy: managament from preconception to the postnatal period. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg3. |

| 18. | American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. 3rd ed. Available from: http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf. |

| 19. | NICE. NICE Clinical Guideline 192. Antenatal and postnatal mental health: clinical management and service guidance. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg192. |

| 20. | Abdollahi F, Zarghami M, Azhar MZ, Sazlina SG, Lye MS. Predictors and incidence of post-partum depression: a longitudinal cohort study. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014;40:2191-2200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ahmed HM, Alalaf SK, Al-Tawil NG. Screening for postpartum depression using Kurdish version of Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;285:1249-1255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bansil P, Kuklina EV, Meikle SF, Posner SF, Kourtis AP, Ellington SR, Jamieson DJ. Maternal and fetal outcomes among women with depression. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2010;19:329-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bener A, Burgut FT, Ghuloum S, Sheikh J. A study of postpartum depression in a fast developing country: prevalence and related factors. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2012;43:325-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Benute GR, Nomura RM, Reis JS, Fraguas Junior R, Lucia MC, Zugaib M. Depression during pregnancy in women with a medical disorder: risk factors and perinatal outcomes. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2010;65:1127-1131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Berger E, Wu A, Smulian EA, Quiñones JN, Curet S, Marraccini RL, Smulian JC. Universal versus risk factor-targeted early inpatient postpartum depression screening. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28:739-744. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Bisson M, Sériès F, Giguère Y, Pamidi S, Kimoff J, Weisnagel SJ, Marc I. Gestational diabetes mellitus and sleep-disordered breathing. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:634-641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Blom EA, Jansen PW, Verhulst FC, Hofman A, Raat H, Jaddoe VW, Coolman M, Steegers EA, Tiemeier H. Perinatal complications increase the risk of postpartum depression. The Generation R Study. BJOG. 2010;117:1390-1398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Bowers K, Laughon SK, Kim S, Mumford SL, Brite J, Kiely M, Zhang C. The association between a medical history of depression and gestational diabetes in a large multi-ethnic cohort in the United States. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2013;27:323-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Burgut FT, Bener A, Ghuloum S, Sheikh J. A study of postpartum depression and maternal risk factors in Qatar. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;34:90-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Callesen NF, Secher AL, Cramon P, Ringholm L, Watt T, Damm P, Mathiesen ER. Mental health in early pregnancy is associated with pregnancy outcome in women with pregestational diabetes. Diabet Med. 2015;32:1484-1491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Chazotte C, Freda MC, Elovitz M, Youchah J. Maternal depressive symptoms and maternal-fetal attachment in gestational diabetes. J Womens Health. 1995;4:375-380. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 32. | Chen CH, Lin HC. Prenatal care and adverse pregnancy outcomes among women with depression: a nationwide population-based study. Can J Psychiatry. 2011;56:273-280. [PubMed] |