Published online Mar 15, 2015. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v6.i2.352

Peer-review started: August 28, 2014

First decision: November 19, 2014

Revised: November 28, 2014

Accepted: December 18, 2014

Article in press: December 19, 2014

Published online: March 15, 2015

Processing time: 204 Days and 3 Hours

The 3-hydroxy-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors, statins, are widely used in the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular diseases to lower serum cholesterol levels. As type 2 diabetes mellitus is accompanied by dyslipidemia, statins have a major role in preventing the long term complications in diabetes and are recommended for diabetics with normal low density lipoprotein levels as well. In 2012, United States Food and Drug Administration released changes to statin safety label to include that statins have been found to increase glycosylated haemoglobin and fasting serum glucose levels. Many studies done on patients with cardiovascular risk factors have shown that statins have diabetogenic potential and the effect varies as per the dosage and type used. The various mechanisms for this effect have been proposed and one of them is downregulation of glucose transporters by the statins. The recommendations by the investigators are that though statins can have diabetogenic risk, they have more long term benefits which can outweigh the risk. In elderly patients and those with metabolic syndrome, as the risk of diabetes increase, the statins should be used cautiously. Other than a subset of population with risk for diabetes; statins still have long term survival benefits in most of the patients.

Core tip: The use of statins in diabetics has long term benefits in terms of decreasing morbidity and mortality. Recent studies have shown that statins increase the incidence of new onset diabetes. The issue became debatable after Food and Drug Administration released changes to statin safety that they increase glycosylated haemoglobin and blood glucose levels. At the same time statins are beneficial in preventing cardiovascular events. Most of the investigators are of the opinion that the risk of diabetes with statins can be outweighed by the long term benefits in preventing complications. In patients with high risk of diabetes, statins should be cautiously used.

- Citation: Chogtu B, Magazine R, Bairy K. Statin use and risk of diabetes mellitus. World J Diabetes 2015; 6(2): 352-357

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v6/i2/352.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v6.i2.352

Statins, the 3-hydroxy-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors, inhibit the rate limiting step of conversion of HMG-CoA to mevalonate and thus limit cholesterol synthesis. Lower hepatic cholesterol levels subsequently increase expression of low density lipoprotein (LDL)-receptors in liver cells. This in turn leads to enhanced clearance of LDL-particles from blood. Lowering of plasma LDL-cholesterol by statins reduce production and increase catabolism of apo B 100[1]. A range of products like coenzyme Q10, heme-A, and isoprenylated proteins are generated by mevalonate pathway[2] which have an important role in cell biology and human physiology. The role of statins has been hypothesized to be widespread as in inflammatory markers and nitric oxide (NO)[3], polyunsaturated fatty acids[4], immunomodulation[5], neuroprotection[6], cellular senescence[7], etc.

Statins are used for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Other benefits due to statins are not mediated by their lipid lowering properties[8] but due to its pleiotropic effects. In conditions like heart failure, cardiac arrhythmias, vascular disease and hypertension the non-lipid lowering pleotropic benefits of statins have been observed[9]. These pleiotropic effects mediated by statins can be due to inhibition of isoprenoid synthesis which in turn inhibits intracellular signaling molecules Rho, Rac and Cdc42. The predominant mechanism that has been postulated is inhibition of Rho and its activation to Rho kinase[10].

Type 2 diabetes is characterized by hyperglycemia, insulin resistance and insulin deficiency. The insulin resistance contributes to the abnormal lipid profile associated with type 2 diabetes[11]. Dyslipidemia contributes to increased cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes[12]. A linear relationship exists between cholesterol levels and cardiovascular diseases in diabetics even if we ignore the baseline LDL[13]. By predominantly lowering LDL-Cholesterol and due to minor effects on other lipoproteins, statins appear to be beneficial[12]. In Heart Protection Study which was done in diabetics, the decrease in cardiovascular events like first major coronary event, stroke were to the tune of 22% as compared to placebo[14]. It was recommended by American Diabetes Association that statin therapy should be initiated in individuals with diabetes and other cardiovascular risk factors with target LDL cholesterol of 100 mg/dL[15]. Investigators are also of the opinion that statin therapy should depend not on the LDL levels but the cardiovascular complications accompanying diabetes[16]. Other studies which showed reduced coronary events with statins in patients with diabetes mellitus are Cholesterol and Recurrent Events and Long-term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease studies of pravastatin[17,18]. In The Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study, statins significantly reduced acute coronary events by 36% and stroke by 48%. The beneficial effects of statins were so clear in this study that it was halted two years in advance[19]. West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study also showed that the risk of diabetes was reduced by 30% in patients on pravastatin 40 mg/d[20].

In February 2012, Food and Drug Administration released changes to statin safety label to include that statins have been found to increase haemoglobin (HbA1C) and fasting serum glucose levels[21]. This release has brought in the debate of using statins in patients with cardiovascular risk factors like diabetes.

In Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention: an Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin study participants with LDL cholesterol levels of less than 130 mg/dL and elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels were included. They received rosuvastatin or placebo for a period of two years. It was observed that rosuvastatin significantly reduced the rates of a first major cardiovascular event and death from any cause as compared to placebo. A 54% lower risk of heart attack, 20% lower risk of stroke and 20% lower risk of death from any cause was noted in statin group[22]. An increase in new onset diabetes, i.e., 3% in statin arm and 2.4% in placebo arm was reported. This was accompanied by increase in median value of glycated haemoglobin and was one of the earlier studies to report the increase in new onset diabetes in patients on statins. Women’s Health Initiative trial was a post hoc analysis and included 153840 postmenopausal women without diabetes mellitus. Even after adjustment for potential confounders, statin therapy was associated with an increased risk of new-onset diabetes mellitus[23]. There was no difference between women with and without overt cardiovascular disease, which could have influenced the risk-benefit ratio of statins[23]. Authors suggest that statin-induced diabetes mellitus is a medication class effect[23]. Another study also reported that as compared to placebo, statin group showed a higher risk of physician reported incident diabetes and it was also observed that risk was higher in women as compared to men[24].

Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials by Sattar et al[25] involving 91140 non-diabetic patients showed that statin therapy was associated with 9% increased risk of incident diabetes. After a period of four years during which 255 patients were treated, there was one extra case of diabetes mellitus[25]. Authors did not find any apparent difference between lipophilic and hydrophilic statins in association with diabetes risk[25].

Though some studies put forth this as a class effect, others showed different effects with different statins and at different doses. A number of studies showed dose dependent association between statin administration and incident diabetes. A meta-analysis with 32752 participants was done in which the risk of intensive dose statin therapy was compared with moderate dose statin therapy on incident diabetes. It revealed that intensive dose of statins was associated with high incidence of new - onset diabetes, though it decreased cardiovascular events as well[26]. In those receiving intensive dose of statins, 18.9 ± 5.2 diabetic cases per 1000 patient years were observed vs 16.9 ± 5.5 cases per 1000 patient years with moderate doses of statin therapy[26].

In PROVE-IT TIMI 22 trial 3382 patients without pre-existing type 2 diabetes mellitus were included. The levels of HbA1C increased by 0.12% in patients treated with pravastatin 40 mg, while in those receiving atorvastatin 80 mg showed a significant difference and the levels increased by 0.30%[27]. Another study comparing glycaemic control between diabetic patients receiving atorvastatin 10 mg, pravastatin 10 mg or pitavastatin 2 mg/d showed that it was only the atorvastatin-treated patients in which the blood glucose and HbA1C levels increased[28]. Treatment with atorvastatin and simvastatin may be associated with an increased risk of new onset diabetes as compared to pravastatin[29]. Pitavastatin has shown favourable profile in patients with diabetes by improving insulin resistance and minimally impairing glucose metabolism[30]. Increased incidence of diabetes was seen with atorvastatin in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial[31] and impaired glucose metabolism in some cases of type 2 diabetes[32]. Increased insulin resistance secondary to statins was demonstrated in a prospective non randomised study in patients with coronary bypass surgery[33]. So, many studies have reported an increase in new onset diabetes and there is a variation in response depending on the statin administered and the dose of statin.

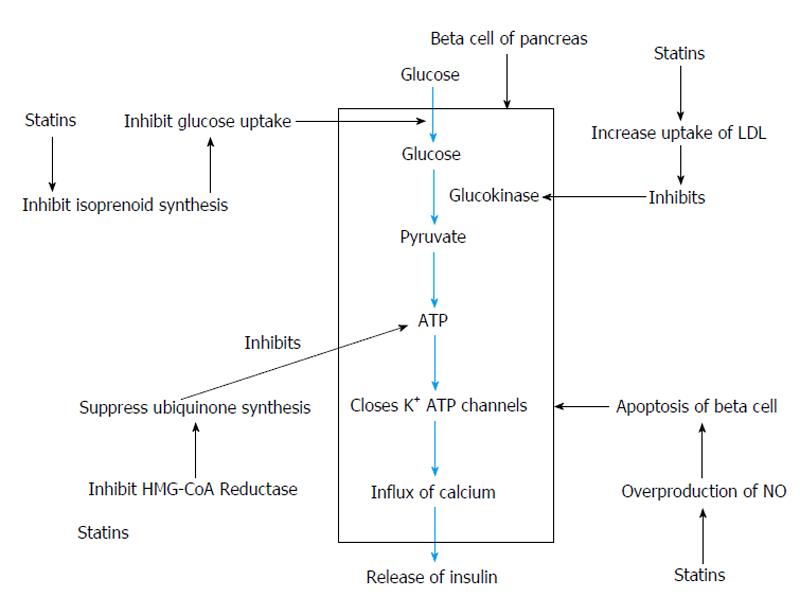

Statin-induced insulin resistance can be due to inhibition of isoprenoid biosynthesis and downregulating C/EBPα production[34]. Decreased synthesis of isoprenoids can produce downregulation of GLUT4 expression on adipocyte cells[35]. It can lead to decrease in insulin-mediated cellular glucose uptake and possibly manifest as intolerance to glucose[36]. Acceleration of type 2 diabetes can be seen secondary to downregulation of GLUT4/SLC2A4 in adipocytes[37]. Over-production of NO by inducing cytokines can cause β-cell apoptosis[38].

On incubating rat pancreatic cells with statin ,there was a decrease in insulin secretion due to inhibition of glucose stimulated increase in free cytoplasmic calcium[39]. Statins also inhibit the insulin secretion due to reduced production of ATP by suppressing the synthesis of ubiquinone (CoQ10)[39]. Clinical doses of atorvastatin in animal model of type 2 diabetes led to inhibition of adipocyte differentiation, decreased SLC2A4 expression in both differentiating and mature adipocytes, and impaired insulin sensitivity and post-challenge glucose tolerance[34]. Animal models have also shown that there is an association between development of insulin resistance and statin-induced myopathy[40].

Other mechanisms hypothesized for the possible effect of statins on new-onset diabetes are that statins by inhibiting phosphorylation interfere with intracellular signal transduction pathways of insulin, reduce action of of small GTPase, decrease peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma by inhibiting the differentiation of adipocytes, inhibit β-cell proliferation and insulin secretion by inhibiting leptins[41]. Atorvastatin, a lipophilic statin, may decrease insulin secretion due to increased HMG-CoA inhibition or cytotoxicity[42]. The actions of statins on beta cells of pancreas can be summarised[43] as shown in Figure 1.

Authors have put forth the recommendations from time to time regarding the use of statins in patients with cardiovascular diseases. For patients with cardiovascular risk factors, statins prevent cardiovascular event 8 times more likely than they can cause a case of incident diabetes[44] shifting the risk-benefit ratio in favour of statin therapy[44]. Modest increase in blood glucose levels by statins will not be an issue of concern if they decrease morbidity and mortality due to macrovascular and microvascular complications[45]. In patients with low cardiovascular risk factors, statins should be cautiously used, less aggressive LDL-C-lowering targets should be kept and monitoring of fasting blood glucose levels should be done routinely[46].

In high risk patients with impaired glucose tolerance and established cardiac risk factors, statins and diuretics increased the risk of new onset diabetes. As both the drugs have a propensity to increase blood glucose levels, there is a need of regular monitoring[47]. As compared to other cardiovascular medications like thiazide diuretics and beta blockers, statins can three times less likely cause diabetes[48].

When statins are being used in primary prevention patients at high risk of diabetes, pravastatin should be preferred over other statins[29]. One of the meta-analysis comparing high-dose statin therapy with moderate dose found that the former is associated with improved cardiovascular outcomes, though at the same time there was a 12% increased risk of new-onset diabetes mellitus[49]. Such studies have stimulated the controversy about the treatment of patients not attaining target lipid profile on moderate dose of statins[49].

Increasing age increases the risk of diabetes and benefits secondary to statins can decrease. There is a need to be vigilant in these patients[50]. Factors like older age, increased weight, and higher blood sugar levels before the use of statins predict that whether a patient will develop diabetes mellitus. The use of statins can unmask diabetes mellitus in patients with other risk factors[51]. So in obese patients and those with metabolic syndrome these findings may be relevant[52]. While analysing one of the initial studies which suggested the link between statins and diabetes, it was found that rate of reduction of cardiovascular events outbalanced the risk of incident diabetes even in patients at highest risk for diabetes though the absolute risk increase was small (placebo 1.2%, rosuvastatin 1.5% developed diabetes[53]). Meta-analysis of individual data of over 170000 persons from 27 randomized trials also put forth the risk benefit ratio in favour of statins[54]. In patients on statins, there was an improved outcome after cardiac surgery[55]. Current guidelines recommend use of statins in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft[56]. Statins can reduce cardiovascular complications like atrial fibrillation and MI after cardiac surgery, but at the same time poor glycemic control may lead to deterioration of non-cardiovascular complications like infections and renal complications[33].

Elevated triglycerides and low HDL-C are associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus. The evidence for drugs targeting this type of dyslipidemia is not as strong as those targeting LDL-C[57].

To conclude, physicians should be cautious about development of diabetes in patients on intensive statin therapy[26]. Lifestyle management should be considered in patients with low risk of cardiovascular diseases[58] and the use of statins should be reconsidered[58]. In patients with cardiovascular risk factors, the benefits of statins supersede the risk of diabetes[59]. There is a need of randomized clinical trials to find the role of statins on microvascular complications as the existing evidence only shows a benefit on macrovascular complications[60]. Overall evidence at present shows that the risk of new onset diabetes is less as compared to the long term benefits of statins in patients with cardiovascular risk factors. But there is a small subgroup of population in whom a more careful use of statins is mandatory.

P- Reviewer: Apikoglu-Rabus S, Huang Y S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Sirtori CR. The pharmacology of statins. Pharmacol Res. 2014;88:3-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 318] [Cited by in RCA: 474] [Article Influence: 43.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Buhaescu I, Izzedine H. Mevalonate pathway: a review of clinical and therapeutical implications. Clin Biochem. 2007;40:575-584. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Cimino M, Gelosa P, Gianella A, Nobili E, Tremoli E, Sironi L. Statins: multiple mechanisms of action in the ischemic brain. Neuroscientist. 2007;13:208-213. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Harris JI, Hibbeln JR, Mackey RH, Muldoon MF. Statin treatment alters serum n-3 and n-6 fatty acids in hypercholesterolemic patients. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2004;71:263-269. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Greenwood J, Steinman L, Zamvil SS. Statin therapy and autoimmune disease: from protein prenylation to immunomodulation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:358-370. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Kivipelto M, Solomon A, Winblad B. Statin therapy in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4:521-522. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Brouilette SW, Moore JS, McMahon AD, Thompson JR, Ford I, Shepherd J, Packard CJ, Samani NJ. Telomere length, risk of coronary heart disease, and statin treatment in the West of Scotland Primary Prevention Study: a nested case-control study. Lancet. 2007;369:107-114. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Wang CY, Liu PY, Liao JK. Pleiotropic effects of statin therapy: molecular mechanisms and clinical results. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14:37-44. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Mihos CG, Pineda AM, Santana O. Cardiovascular effects of statins, beyond lipid-lowering properties. Pharmacol Res. 2014;88:12-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhou Q, Liao JK. Pleiotropic effects of statins - Basic research and clinical perspectives -. Circ J. 2010;74:818-826. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Adiels M, Olofsson SO, Taskinen MR, Borén J. Diabetic dyslipidaemia. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2006;17:238-246. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Brunzell JD, Davidson M, Furberg CD, Goldberg RB, Howard BV, Stein JH, Witztum JL. Lipoprotein management in patients with cardiometabolic risk: consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:811-822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 391] [Cited by in RCA: 382] [Article Influence: 22.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Stamler J, Vaccaro O, Neaton JD, Wentworth D. Diabetes, other risk factors, and 12-yr cardiovascular mortality for men screened in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Diabetes Care. 1993;16:434-444. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Collins R, Armitage J, Parish S, Sleigh P, Peto R. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol-lowering with simvastatin in 5963 people with diabetes: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361:2005-2016. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Haffner SM. Dyslipidemia management in adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27 Suppl 1:S68-S71. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Eldor R, Raz I. American Diabetes Association indications for statins in diabetes: is there evidence? Diabetes Care. 2009;32 Suppl 2:S384-S391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lewis SJ, Sacks FM, Mitchell JS, East C, Glasser S, Kell S, Letterer R, Limacher M, Moye LA, Rouleau JL. Effect of pravastatin on cardiovascular events in women after myocardial infarction: the cholesterol and recurrent events (CARE) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:140-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Keech A, Colquhoun D, Best J, Kirby A, Simes RJ, Hunt D, Hague W, Beller E, Arulchelvam M, Baker J. Secondary prevention of cardiovascular events with long-term pravastatin in patients with diabetes or impaired fasting glucose: results from the LIPID trial. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2713-2721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Durrington P. Clinical trials of lipid-lowering medication in diabetes. Br J Diabetes Vasc Dis. 2003;3:217-220. |

| 20. | Kotseva K, Wood D, De Backer G, De Bacquer D, Pyörälä K, Keil U. Cardiovascular prevention guidelines in daily practice: a comparison of EUROASPIRE I, II, and III surveys in eight European countries. Lancet. 2009;373:929-940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 602] [Cited by in RCA: 628] [Article Influence: 39.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | FDA Drug Safety Communication. Important safety label changes to cholesterol lowering statin drugs. 2012; Available from: http: //www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm293101.htm. |

| 22. | Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, Genest J, Gotto AM, Kastelein JJ, Koenig W, Libby P, Lorenzatti AJ, MacFadyen JG. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2195-2207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4679] [Cited by in RCA: 4791] [Article Influence: 281.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Culver AL, Ockene IS, Balasubramanian R, Olendzki BC, Sepavich DM, Wactawski-Wende J, Manson JE, Qiao Y, Liu S, Merriam PA. Statin use and risk of diabetes mellitus in postmenopausal women in the Women’s Health Initiative. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:144-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 291] [Cited by in RCA: 344] [Article Influence: 26.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Mora S, Glynn RJ, Hsia J, MacFadyen JG, Genest J, Ridker PM. Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events in women with elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein or dyslipidemia: results from the Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention: An Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin (JUPITER) and meta-analysis of women from primary prevention trials. Circulation. 2010;121:1069-1077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sattar N, Preiss D, Murray HM, Welsh P, Buckley BM, de Craen AJ, Seshasai SR, McMurray JJ, Freeman DJ, Jukema JW. Statins and risk of incident diabetes: a collaborative meta-analysis of randomised statin trials. Lancet. 2010;375:735-742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1657] [Cited by in RCA: 1735] [Article Influence: 115.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Preiss D, Seshasai SR, Welsh P, Murphy SA, Ho JE, Waters DD, DeMicco DA, Barter P, Cannon CP, Sabatine MS. Risk of incident diabetes with intensive-dose compared with moderate-dose statin therapy: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;305:2556-2564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1001] [Cited by in RCA: 1032] [Article Influence: 73.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Sabatine MS, Wiviott SD, Morrow DA, McCabe CH, Cannon CP. High-dose atorvastatin associated with worse glycemic control: a PROVE-IT TIMI 22 substudy. Circulation. 2004;110 Suppl I:S834. |

| 28. | Yamakawa T, Takano T, Tanaka S, Kadonosono K, Terauchi Y. Influence of pitavastatin on glucose tolerance in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2008;15:269-275. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Carter AA, Gomes T, Camacho X, Juurlink DN, Shah BR, Mamdani MM. Risk of incident diabetes among patients treated with statins: population based study. BMJ. 2013;346:f2610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 277] [Cited by in RCA: 290] [Article Influence: 24.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kawai Y, Sato-Ishida R, Motoyama A, Kajinami K. Place of pitavastatin in the statin armamentarium: promising evidence for a role in diabetes mellitus. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2011;5:283-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Sever PS, Dahlöf B, Poulter NR, Wedel H, Beevers G, Caulfield M, Collins R, Kjeldsen SE, Kristinsson A, McInnes GT. Prevention of coronary and stroke events with atorvastatin in hypertensive patients who have average or lower-than-average cholesterol concentrations, in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial--Lipid Lowering Arm (ASCOT-LLA): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361:1149-1158. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Diabetes Atorvastin Lipid Intervention (DALI) Study Group. The effect of aggressive versus standard lipid lowering by atorvastatin on diabetic dyslipidemia: the DALI study: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in patients with type 2 diabetes and diabetic dyslipidemia. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1335-1341. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Sato H, Carvalho G, Sato T, Hatzakorzian R, Lattermann R, Codere-Maruyama T, Matsukawa T, Schricker T. Statin intake is associated with decreased insulin sensitivity during cardiac surgery. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:2095-2099. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Nakata M, Nagasaka S, Kusaka I, Matsuoka H, Ishibashi S, Yada T. Effects of statins on the adipocyte maturation and expression of glucose transporter 4 (SLC2A4): implications in glycaemic control. Diabetologia. 2006;49:1881-1892. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Graham I, Atar D, Borch-Johnsen K, Boysen G, Burell G, Cifkova R, Dallongeville J, De Backer G, Ebrahim S, Gjelsvik B. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: executive summary: Fourth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (Constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts). Eur Heart J. 2007;28:2375-2414. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Kanda M, Satoh K, Ichihara K. Effects of atorvastatin and pravastatin on glucose tolerance in diabetic rats mildly induced by streptozotocin. Biol Pharm Bull. 2003;26:1681-1684. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Abel ED, Peroni O, Kim JK, Kim YB, Boss O, Hadro E, Minnemann T, Shulman GI, Kahn BB. Adipose-selective targeting of the GLUT4 gene impairs insulin action in muscle and liver. Nature. 2001;409:729-733. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Nakata M, Uto N, Maruyama I, Yada T. Nitric oxide induces apoptosis via Ca2+-dependent processes in the pancreatic beta-cell line MIN6. Cell Struct Funct. 1999;24:451-455. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Yada T, Nakata M, Shiraishi T, Kakei M. Inhibition by simvastatin, but not pravastatin, of glucose-induced cytosolic Ca2+ signalling and insulin secretion due to blockade of L-type Ca2+ channels in rat islet beta-cells. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;126:1205-1213. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Mallinson JE, Constantin-Teodosiu D, Sidaway J, Westwood FR, Greenhaff PL. Blunted Akt/FOXO signalling and activation of genes controlling atrophy and fuel use in statin myopathy. J Physiol. 2009;587:219-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Brault M, Ray J, Gomez YH, Mantzoros CS, Daskalopoulou SS. Statin treatment and new-onset diabetes: a review of proposed mechanisms. Metabolism. 2014;63:735-745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Ishikawa M, Namiki A, Kubota T, Yajima S, Fukazawa M, Moroi M, Sugi K. Effect of pravastatin and atorvastatin on glucose metabolism in nondiabetic patients with hypercholesterolemia. Intern Med. 2006;45:51-55. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Sattar N, Taskinen MR. Statins are diabetogenic--myth or reality? Atheroscler Suppl. 2012;13:1-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Bhatia L, Byrne CD. There is a slight increase in incident diabetes risk with the use of statins, but benefits likely outweigh any adverse effects in those with moderate -to-high cardiovascular risk. Evidence Based Medicine. 2010;15:84-85. |

| 45. | Belalcazar LM, Raghavan VA, Ballantyne CM. Statin-induced diabetes: will it change clinical practice? Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1941-1943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Rocco MB. Statins and diabetes risk: fact, fiction, and clinical implications. Cleve Clin J Med. 2012;79:883-893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Shen L, Shah BR, Reyes EM, Thomas L, Wojdyla D, Diem P, Leiter LA, Charbonnel B, Mareev V, Horton ES. Role of diuretics, β blockers, and statins in increasing the risk of diabetes in patients with impaired glucose tolerance: reanalysis of data from the NAVIGATOR study. BMJ. 2013;347:f6745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Elliott WJ, Meyer PM. Incident diabetes in clinical trials of antihypertensive drugs: a network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2007;369:201-207. [PubMed] |

| 49. | Davidson MH. Pharmacotherapy: Implications of high-dose statin link with incident diabetes. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;8:543-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 50. | Gale EAM. Statin-induced diabetes [internet]. 2014;. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 51. | Shah RV, Goldfine AB. Statins and risk of new-onset diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2012;126:e282-e284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Mancini GB, Hegele RA, Leiter LA. Dyslipidemia. Can J Diabetes. 2013;37 Suppl 1:S110-S116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Ridker PM, Pradhan A, MacFadyen JG, Libby P, Glynn RJ. Cardiovascular benefits and diabetes risks of statin therapy in primary prevention: an analysis from the JUPITER trial. Lancet. 2012;380:565-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 551] [Cited by in RCA: 601] [Article Influence: 46.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Mihaylova B, Emberson J, Blackwell L, Keech A, Simes J, Barnes EH, Voysey M, Gray A, Collins R, Baigent C. The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with statin therapy in people at low risk of vascular disease: meta-analysis of individual data from 27 randomised trials. Lancet. 2012;380:581-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1891] [Cited by in RCA: 1976] [Article Influence: 152.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Kuhn EW, Liakopoulos OJ, Choi YH, Wahlers T. Current evidence for perioperative statins in cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:372-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Eagle KA, Guyton RA, Davidoff R, Edwards FH, Ewy GA, Gardner TJ, Hart JC, Herrmann HC, Hillis LD, Hutter AM. ACC/AHA 2004 guideline update for coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Update the 1999 Guidelines for Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery). Circulation. 2004;110:e340-e437. [PubMed] |

| 57. | Singh IM, Shishehbor MH, Ansell BJ. High-density lipoprotein as a therapeutic target: a systematic review. JAMA. 2007;298:786-798. [PubMed] |

| 58. | Park ZH, Juska A, Dyakov D, Patel RV. Statin-associated incident diabetes: a literature review. Consult Pharm. 2014;29:317-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Axsom K, Berger JS, Schwartzbard AZ. Statins and diabetes: the good, the bad, and the unknown. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2013;15:299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Rajpathak SN, Kumbhani DJ, Crandall J, Barzilai N, Alderman M, Ridker PM. Statin therapy and risk of developing type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1924-1929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 294] [Cited by in RCA: 326] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |