Published online Apr 15, 2014. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v5.i2.224

Revised: March 10, 2014

Accepted: March 17, 2014

Published online: April 15, 2014

Processing time: 140 Days and 18.1 Hours

We experienced a case of liver abscess due to Clostridium perfringens (CP) complicated with massive hemolysis and rapid death in an adequately controlled type 2 diabetic patient. The patient died 6 h after his first visit to the hospital. CP was later detected in a blood culture. We searched for case reports of CP septicemia and found 124 cases. Fifty patients survived, and 74 died. Of the 30 patients with liver abscess, only 3 cases survived following treatment with emergency surgical drainage. For the early detection of CP infection, detection of Gram-positive rods in the blood or drainage fluid is important. Spherocytes and ghost cells indicate intravascular hemolysis. The prognosis is very poor once massive hemolysis occurs. The major causative organisms of gas-forming liver abscess in diabetic patients are Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae) and Escherichia coli (E. coli). Although CP is relatively rare, the survival rate is very poor compared with those of K. pneumoniae and E. coli. Therefore, for every case that presents with a gas-forming liver abscess, the possibility of CP should be considered, and immediate aspiration of the abscess and Gram staining are important.

Core tip: Gas-forming liver abscess caused by Clostridium perfringens can result in massive hemolysis and death within several hours. For survival, urgent surgical intervention and antibiotic administration are necessary.

- Citation: Kurasawa M, Nishikido T, Koike J, Tominaga SI, Tamemoto H. Gas-forming liver abscess associated with rapid hemolysis in a diabetic patient. World J Diabetes 2014; 5(2): 224-229

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v5/i2/224.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v5.i2.224

Gas-forming infections are an example of a severe type of infection in diabetic patients. Although life threatening, there still remains time for treatment[1,2]. However, in rare cases of Clostridium perfringens (CP) infection, the time remaining for the patient is very limited[3-7]. CP is an anaerobic Gram-positive rod that is found in the soil and the human gastrointestinal and urogenital tracts. CP causes septicemia in cases of food intoxication, wound-associated soft tissue infections, liver abscess, and lung abscess. CP may cause septicemia without any apparent wound through bacterial translocation[5-8]. Patients typically have an underlying condition such as diabetes, malignancy, liver cirrhosis, or an immunosuppressive state[4-23]. In some reports, CP septicemia occurred after an invasive procedure in the hepatobiliary tract[24-26] or gastrointestinal tract or following gynecological treatment[27,28] or line insertion[29]. Early diagnosis is difficult because only nonspecific inflammation and gas formation in the focus are present. However, once α-toxin triggers hemolysis, it progresses very rapidly and is followed by acidosis and renal failure[30,31]. According to the literature, the mortality rate ranges from 70% to 100%[3]. For survival, surgical removal of the focus, appropriate antibiotics, control of hemolysis, and supportive care including hemodialysis are necessary. These treatments should be started before the blood culture result is returned. For early diagnosis, the detection of spherocytes and Gram-positive rods in the blood is important[5,32,33]. We experienced a case of liver abscess in an adequately controlled diabetic patient without any triggering event. The patient died within hours following massive hemolysis and cardiac arrest. Although the majority of gas-forming infections in diabetics are caused by Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae)[34], the possibility of CP infection should be considered.

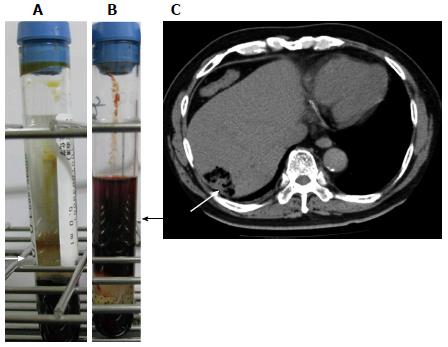

The patient was a 65-year-old Brazilian of Japanese origin. He had a 3-day history of fever, appetite loss, nausea, and upper abdominal pain. The patient had type 2 diabetes treated with an oral hypoglycemic agent. He also had hypertension and dyslipidemia. He had a history of coronary stenting but no history of liver cirrhosis or malignancy. On physical examination, consciousness was clear, his blood pressure was 157/90 mmHg, and hyperventilation and coldness of the limbs were noted. Slight scleral jaundice and slight tenderness of the abdomen were noted. Laboratory examinations indicated mild liver dysfunction and elevation of serum bilirubin, C-reactive protein, and the white blood cell count (Table 1). At this time, the serum did not show any sign of intravascular hemolysis (Figure 1A). CT of the abdomen revealed a liver abscess 4 cm in diameter with gas formation in the right lobe (Figure 1C). A blood culture sample was taken, and ceftriaxone injection was started immediately. The patient briefly returned to his dormitory to prepare for admission and was found unconscious by a fellow worker. He was transferred to the hospital, and CPR was performed in vain. The serum color at this time point revealed strong hemolysis (Figure 1B). He died 6 h after his first visit to the hospital. The remarkably high levels of serum potassium (11.8 mEq/L) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (6203 IU/L) during CPR suggested massive intravascular hemolysis. CP was later detected in the blood culture. Autopsy was refused, and we were unable to determine whether he had an occult malignancy.

| Parameter | Admission | On CPR | Reference range |

| White blood count (× 109/L) | 24.8 | 26.0 | 3.5 to 9.7 |

| Red blood count (× 109/L) | 4980 | 1280 | 4380 to 5770 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 135 | 81 | 136 to 183 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 40.7 | 10.8 | 40.4 to 51.9 |

| Platelet (× 109/L) | 243 | 118.8 | 140 to 379 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 6.4 | 6.96 | 0.2 to 1.0 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (IU/L) | 140 | 261 | 8 to 38 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/L) | 102 | 297 | 4 to 44 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | 178 | 469 | 104 to 338 |

| γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (IU/L) | 25 | 6 | 18 to 66 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (IU/L) | 373 | 6203 | 106 to 211 |

| Creatine phosphokinase (IU/L) | 220 | 438 | 104 to 338 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 24.2 | 30.5 | 8 to 20 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.33 | 1.12 | 0.63 to 1.03 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 134 | 128 | 137 to 147 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 4.6 | 11.8 | 3.5 to 5.0 |

| Chloride (mEq/L) | 95 | 84 | 98 to 108 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) | 23.2 | 16.0 | < 0.30 |

| International normalized ratio | 1.05 | 19.4 | 0.9 to 1.1 |

| APTT (s) | 38 | 122.9 | 25 to 40 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 226 | 129 |

Recently, van Bunderen et al[3] reported 40 cases of CP septicemia and hemolysis between 1990 and 2010. In total, 80% of the patients had died; among the 11 cases with liver abscess, 10 (90.9%) had died. These 10 cases included two cases of microabscess. In one case, the focus of infection was removed, and the patient survived. On the other hand, Fujita et al[35] studied patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) with CP-positive blood cultures and reported that 5 of 18 cases had died (27.8%). Yang et al[36] reported the prognosis of CP septicemia in a tertiary care hospital. They found 93 cases over 10 years, and the 30-d mortality rate was 26.9%. Therefore, the mortality rate of CP septicemia differs considerably. We hypothesized that the complication of liver abscess decreases the survival rate. We searched PubMed for papers published since 2010 and the database of the Japan Medical Abstract Society since 1994 with the keywords “Clostridium perfringens” and “septicemia”. We found 20 cases from PubMed and 104 cases from Japan, including our case[4-33,35,37-39]. Fifty patients survived, and 74 (59.7%) died.

Several possible triggers of septicemia were found, including transarterial embolization of the hepatoma[24,25], laparoscopic cholecystectomy[26], amniocentesis[27], abortion[28], and intravenous line insertion[29]. Among the 30 cases with liver abscess, 27 (90%) died. Six cases underwent drainage or laparotomy, and three cases survived[8,30,38]. Among the cases with liver abscess, 23 were male and 7 were female; the average patient age was 67.2 years old, and 11 patients had diabetes. The median time from the first visit to death was only 6 h. Of the 74 deceased patients, 45 were male, 21 were female, and 8 were not described; the average age was 64.4 years old. Malignancy was the frequent underlying disease. Twenty-one cases had a history of cancer in the liver, stomach, colon, rectum, gall bladder, biliary duct, lung, pancreas, breast, prostate gland, or uterus. Ten cases had a history of leukemia, lymphoma, or multiple myeloma. One patient had a brain tumor. In total, 30 cases (45.5%) had a history of at least one malignancy. Eighteen cases had diabetes. Four cases had liver cirrhosis. The median time from the first visit to death was 6 h. Only 12 cases (16%) had undergone emergency surgery or drainage. Two patients received hemoperfusion using a polymyxin B-immobilized fiber column (PMX-F), which is used for endotoxin removal in Japan and Italy[40-43]. Of the 50 surviving patients, 16 were male, 19 were female, and 15 were not described. Females were significantly more prevalent among the survivors, according to a chi-squared test (P < 0.05). Three cases involved children younger than 2 years old. The average age, excluding these small children, was 58.1 years. The age difference between the deceased and surviving cases was not significant (P = 0.06), according to a two-sided t test. Six cases had leukemia, and 4 cases had cancer or sarcoma in the breast, uterus, or colon. Six cases had diabetes. Twenty (40%) cases underwent surgical removal or drainage of the focus. A significantly greater number of patients who underwent surgical debridement or drainage were among the surviving cases compared with the deceased cases, according to a chi-squared test (P < 0.01). PMX-F was used to treat 5 patients who survived. Among the surviving cases, steroid pulse therapy was performed in three cases and hyperbaric oxygen therapy was used in two.

Although our case did not show anemia at first presentation and the size of liver abscess was only 4 cm, he developed massive fatal hemolysis within hours, despite prompt treatment with the appropriate antibiotics. Therefore, CP septicemia should be considered in diabetic patients with fever and gas-forming lesions before any signs of hemolysis develop. van Bunderen et al[3] reported 40 cases of septicemia caused by CP during 1990-2010. Over half of the patients presented elevated bilirubin and LDH as well as anemia, suggesting hemolysis at the initial presentation. Thirty-two of the patients died, and the median time from admission to death was only 8 h. We searched new cases of CP septicemia. We found 124 cases, and the death rate was 59.7%. However, in cases with liver abscess, the death rate reached 90%, and the median time from visit to death was only 6 h. Rapid hemolysis caused by α-toxin is an important complication that makes rescue difficult. The α-toxin of CP has two domains plus one loop in between. The N-terminal domain has phospholipase activity, and the C-terminal domain is hydrophobic and inserts into the cell membrane[44]. The loop between the N- and C-terminal domains contains a GM1 ganglioside-binding motif and specifically binds GM1a. In addition to disrupting membrane phospholipids through phospholipase activity, α-toxin binding to GM1a triggers specific signaling events. The activation of a tyrosine kinase A (TrkA)[45] and the subsequent signaling cascade results in the release of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). The catastrophic events induced by α-toxin may in part be mediated by TNF-α signaling. The hemolysis of erythrocytes by α-toxin is reported to depend on Ca2+ uptake[46].

The key for patient rescue is how fast the appropriate treatments are started. At the moment of suspicion of CP septicemia, aggressive early management is warranted, including timely debridement or drainage of the focus, initiation of appropriate antibiotics without delay, and support of circulation with a multi-disciplinary team approach. For the early diagnosis of CP infection, Gram staining of the blood or drainage sample is important because CP is a Gram-positive rod, whereas K. pneumoniae and E. coli are Gram negative. The early signs of hemolysis are elevated LDH, total or indirect bilirubin, and potassium. Spherocytes or ghost cells may be found in the blood film. A red color of the serum or hemoglobinuria may be observed after substantial hemolysis.

Shah et al[47] reported 25 cases of CP septicemia in a tertiary-care hospital from 1995 to 2003 and classified antibiotics into two categories. The antibiotics classified as “appropriate” for Clostridium were penicillin G, clindamycin, cefoxitin, metronidazole, ampicillin/sulbactam, piperacillin/tazobactam, and imipenem/cilastatin; other antibiotics were classified as “insufficient”. Patients treated with “insufficient” antibiotics had a significantly higher 2-d mortality rate (75%) compared with patients treated with “appropriate” antibiotics (12.5%). Clindamycin, metronidazole, and rifampicin have been shown to be effective methods to reduce the release of α-toxin[48]. However, penicillin and cephalosporin do not have such activity. Oda et al[49] have reported that erythromycin pretreatment reduces the release of TNF-α from activated neutrophils and suppresses hemolysis.

Because α-toxin has enzymatic activity, methods to neutralize or eliminate this toxin are needed. Unfortunately, we were unable to find any established method of doing so. PMX-F is used in septic shock treatment. PMX-F binds endotoxin, monocytes, activated neutrophils, and anandamide, decreasing inflammatory cytokines and other mediators. A review by Cruz et al[40] analyzed 987 patients treated with PMX-F and 447 patients treated with conventional medical therapies. PMX-F increased the mean arterial pressure by 19 mmHg while reducing the dopamine/dobutamine dose by 1.8 μg/kg per min. PMX-F therapy was associated with a significantly lower mortality risk (RR = 0.53; 95%CI: 0.43-0.65). However, the number of reported cases is currently too small to discuss the effectiveness of PMX-F in the treatment of CP septicemia. Ochi et al[46] reported that flunarizine, a T-type Ca2+ channel blocker and tetrandrine, an L- and T-type Ca2+ channel blocker, inhibited hemolysis by α-toxin. Nagahama et al[50] reported that the C-terminal recombinant peptide of α-toxin was effective as a vaccine to protect against hemolysis in an animal experiment.

Empirical antibiotic therapy should be started before the culture results are returned. The major causative organisms of gas-forming liver abscesses are K. pneumoniae and E. coli[1,2,34]. These organisms can also cause fatal infections, and endophthalmitis or meningitis may occur[51], but the mortality rate is not as high as that of CP. A review of 46 cases reported death in K. pneumoniae liver abscess for 11 of 43 (25.6%) patients[51]. According to a report from China, 95% of the patients with liver abscess were eventually cured if treated radically[34]. Fortunately, CP septicemia is rare. Kasai et al[52] reported that among cases of severe infection in diabetic patients in Japan, 119 cases presented with a gas-forming abscess, and only 8 cases were positive for Clostridium. Kurai et al[53] reported that among 5011 blood samples that were positive for any bacteria, only 41 were positive for Clostridium. Of the 41 samples, 16 were confirmed as septicemia, and 9 of the 16 were positive for CP. According to a report from Canada, the incidence of CP septicemia in the community is 0.7 in 100000 per year[54]. Additionally, in hospital-based studies, CP septicemia is very rare. Zahar reported 45 cases of anaerobic bacteremia among 7989 positive blood cultures in a cancer center during 1993-1998[55]; seven of them were CP septicemia. Woo et al[53] reported 38 cases of Clostridium septicemia in a large hospital from 1998 to 2001; 79% of them were caused by CP, and the overall mortality was 29%. Younger age and gastrointestinal/hepatobiliary tract disease were associated with mortality. However, considering the very high mortality rate associated with liver abscess, excluding CP infection is important.

In summary, CP septicemia is a rare but well-known cause of massive intravascular hemolysis. Diabetic patients with fever and gas-forming lesions should always be suspected of having CP septicemia.

A 65-year-old male with treated diabetes presented with fever and upper abdominal pain.

Hypertension, hyperventilation, coldness of limbs, scleral jaundice, and tenderness of the abdomen were noted.

Obstructive jaundice complicated with biliary infection and liver abscess.

White blood cell 24.8 × 109/L, hemoglobin 135 g/L, total bilirubin 6.4 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase 140 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase 178 IU/L, creatinine 1.33 mg/dL, C-reactive protein 23.2 mg/dL, and glucose 226 mg/dL.

Computed tomography imaging showed a gas-forming mass (4 cm × 2 cm) in the right lobe of the liver.

Autopsy was not allowed, and blood culture revealed infection by Clostridium perfringens.

Injection of ceftriaxone was started immediately.

The reported mortality rate of Clostridium perfringens septicemia varies widely from 26.9% to 80%; however, 90% of patients with liver abscess have been reported to die.

Polymyxin B-immobilized fiber column (PMX-F) is hemoperfusion with a polymyxin B-immobilized fiber column used to remove endotoxin in cases of septic shock.

Although rare, fatal liver abscess patients should be under close observation, and the possibility of Clostridium perfringens infection should be considered upon the slightest sign of hemolysis.

This is a well written manuscript in which the author gave detailed description of death report associated with CP infection.

P- Reviewers: Elisaf MS, Ferraioli G, Peng B S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Tatsuta T, Wada T, Chinda D, Tsushima K, Sasaki Y, Shimoyama T, Fukuda S. A case of gas-forming liver abscess with diabetes mellitus. Intern Med. 2011;50:2329-2332. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Hagiya H, Kuroe Y, Nojima H, Otani S, Sugiyama J, Naito H, Kawanishi S, Hagioka S, Morimoto N. Emphysematous liver abscesses complicated by septic pulmonary emboli in patients with diabetes: two cases. Intern Med. 2013;52:141-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | van Bunderen CC, Bomers MK, Wesdorp E, Peerbooms P, Veenstra J. Clostridium perfringens septicaemia with massive intravascular haemolysis: a case report and review of the literature. Neth J Med. 2010;68:343-346. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Smith AM, Thomas J, Mostert PJ. Fatal case of Clostridium perfringens enteritis and bacteraemia in South Africa. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2011;5:400-402. [PubMed] |

| 5. | McIlwaine K, Leach MT. Clostridium perfringens septicaemia. Br J Haematol. 2013;163:549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gas Gangrene Caused By Clostridium Perfringens Involving the Liver, Spleen , and Heart in a Man 20 Years After an Orthotopic Liver Transplant: A Case Report. Exp Clin Transplant. 2013;12:165-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Okon E, Bishburg E, Ugras S, Chan T, Wang H. Clostridium perfringens meningitis, Plesiomonas shigelloides sepsis: A lethal combination. Am J Case Rep. 2013;14:70-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rajendran G, Bothma P, Brodbeck A. Intravascular haemolysis and septicaemia due to Clostridium perfringens liver abscess. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2010;38:942-945. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Atia A, Raiyani T, Patel P, Patton R, Young M. Clostridium perfringens bacteremia caused by choledocholithiasis in the absence of gallbladder stones. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5632-5634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mutters NT, Stoffels S, Eisenbach C, Zimmermann S. Ischaemic intestinal perforation complicated by Clostridium perfringens sepsis in a diabetic patient. Infection. 2013;41:1033-1035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hugelshofer M, Achermann Y, Kovari H, Dent W, Hombach M, Bloemberg G. Meningoencephalitis with subdural empyema caused by toxigenic Clostridium perfringens type A. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:3409-3411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lazarescu C, Kimmoun A, Blatt A, Bastien C, Levy B. Clostridium perfringens gangrenous cystitis with septic shock and bone marrow necrosis. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:1906-1907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Salvador C, Kropshofer G, Niederwanger C, Trieb T, Meister B, Neu N, Müller T. Fulminant Clostridium perfringens sepsis during induction chemotherapy in childhood leukemia. Pediatr Int. 2012;54:424-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Adams BN, Lekovic JP, Robinson S. Clostridium perfringens sepsis following a molar pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210:e13-e14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Juntermanns B, Radunz S, Heuer M, Vernadakis S, Reis H, Gallinat A, Treckmann J, Kaiser G, Paul A, Saner F. Fulminant septic shock due to Clostridium perfringens skin and soft tissue infection eight years after liver transplantation. Ann Transplant. 2011;16:143-146. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Watt J, Amini A, Mosier J, Gustafson M, Wynne JL, Friese R, Gruessner RW, Rhee P, O’Keeffe T. Treatment of severe hemolytic anemia caused by Clostridium perfringens sepsis in a liver transplant recipient. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2012;13:60-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ohtani S, Watanabe N, Kawata M, Harada K, Himei M, Murakami K. Massive intravascular hemolysis in a patient infected by a Clostridium perfringens. Acta Med Okayama. 2006;60:357-360. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Kuroda S, Okada Y, Mita M, Okamoto Y, Kato H, Ueyama S, Fujii I, Morita S, Yoshida Y. Fulminant massive gas gangrene caused by Clostridium perfringens. Intern Med. 2005;44:499-502. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Ito M, Takahashi N, Saitoh H, Shida S, Nagao T, Kume M, Kameoka Y, Tagawa H, Fujishima N, Hirokawa M. Successful treatment of necrotizing fasciitis in an upper extremity caused by Clostridium perfringens after bone marrow transplantation. Intern Med. 2011;50:2213-2217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kurashina R, Shimada H, Matsushima T, Doi D, Asakura H, Takeshita T. Spontaneous uterine perforation due to clostridial gas gangrene associated with endometrial carcinoma. J Nippon Med Sch. 2010;77:166-169. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Terada K, Kawano S, Kataoka N and Morita T. Bacteremia of Clostridium difficile and Clostridium perfringens with transient eosinophilia in a premature infant. Kawasaki Medical J. 1990;16:71-74. |

| 22. | Kimura C, Miura A, Sato I, Suzuki S. [Acute myelocytic leukemia associated with Clostridium perfringens (CP) septicemia: report of 3 cases]. Nihon Naika Gakkai Zasshi. 1994;83:1351-1352. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Shetty P, Deans R, Abbott J. A case of Clostridium perfringens infection in uterine sarcoma. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;50:495-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Nakanishi H, Chuganji Y, Uraushihara K, Yamamoto T, Araki A, Sazaki N, Momoi M, Kawahara Y. An autopsy case of the hepatocellular carcinoma associated with multiple myeloma which developed fatal massive hemolysis due to the Clostridium perfringens septicemia following TAE. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2003;100:1395-1399. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Kashimura S, Fujita Y, Imamura S, Shimizu T, Imai J, Tsunoda Y, Ito T, Nagakubo S, Morohoshi Y, Mizukami T and Komatsu H. An autopsy case of hepatocellu; ar carcinoma, which developed a fatal massive hemolysis as a complication of Clostridium perfringens infection after transarterial chemoembolization. Kanzo. 2012;53:175-182. |

| 26. | Ch’ng JK, Ng SY, Goh BK. An unusual cause of sepsis after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:e1-e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hendrix NW, Mackeen AD, Weiner S. Clostridium perfringens Sepsis and Fetal Demise after Genetic Amniocentesis. AJP Rep. 2011;1:25-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Stroumsa D, Ben-David E, Hiller N, Hochner-Celnikier D. Severe Clostridial Pyomyoma following an Abortion Does Not Always Require Surgical Intervention. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2011;2011:364641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Determann C, Walker CA. Clostridium perfringens gas gangrene at a wrist intravenous line insertion. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ng H, Lam SM, Shum HP, Yan WW. Clostridium perfringens liver abscess with massive haemolysis. Hong Kong Med J. 2010;16:310-312. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Law ST, Lee MK. A middle-aged lady with a pyogenic liver abscess caused by Clostridium perfringens. World J Hepatol. 2012;4:252-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kitamura T. Clostridium perfringens detected by peripheral blood smear. Intern Med. 2012;51:447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Shoda T, Yoshimura M, Hayata D, Miyazawa Y, Ogata K. Marked spherocytosis in clostridal sepsis. Int J Hematol. 2006;83:179-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Tian LT, Yao K, Zhang XY, Zhang ZD, Liang YJ, Yin DL, Lee L, Jiang HC, Liu LX. Liver abscesses in adult patients with and without diabetes mellitus: an analysis of the clinical characteristics, features of the causative pathogens, outcomes and predictors of fatality: a report based on a large population, retrospective study in China. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:E314-E330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Fujita H, Nishimura S, Kurosawa S, Akiya I, Nakamura-Uchiyama F, Ohnishi K. Clinical and epidemiological features of Clostridium perfringens bacteremia: a review of 18 cases over 8 year-period in a tertiary care center in metropolitan Tokyo area in Japan. Intern Med. 2010;49:2433-2437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Yang CC, Hsu PC, Chang HJ, Cheng CW, Lee MH. Clinical significance and outcomes of Clostridium perfringens bacteremia--a 10-year experience at a tertiary care hospital. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17:e955-e960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Nagami H, Matsui Y. Challenge of acute lumber pain: clinical experience of four cases of acute pyogenic spondylodiscitis. Shimane J Med Science. 2012;28:133-141. |

| 38. | Sato N, Kitamura M, Kanno H and Gotoh M. Rupture of a gas-containing liver abscess due to Clostridium perfringens treated by laparotomy drainage. J Jpn Surg Association. 2012;73:2014-2020. |

| 39. | Sekino M, Ichinomiya T, Higashijima U, Yoshitomi O, Nakamura T, Furumoto A, Makita T and Sumikawa K. A case of Clostridium perfringens septicemia with massive intravascular hemolysis. J Jpn Soc Intensive Care Med. 2013;20:38-42. |

| 40. | Cruz DN, Perazella MA, Bellomo R, de Cal M, Polanco N, Corradi V, Lentini P, Nalesso F, Ueno T, Ranieri VM. Effectiveness of polymyxin B-immobilized fiber column in sepsis: a systematic review. Crit Care. 2007;11:R47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Zagli G, Bonizzoli M, Spina R, Cianchi G, Pasquini A, Anichini V, Matano S, Tarantini F, Di Filippo A, Maggi E. Effects of hemoperfusion with an immobilized polymyxin-B fiber column on cytokine plasma levels in patients with abdominal sepsis. Minerva Anestesiol. 2010;76:405-412. [PubMed] |

| 42. | Berto P, Ronco C, Cruz D, Melotti RM, Antonelli M. Cost-effectiveness analysis of polymyxin-B immobilized fiber column and conventional medical therapy in the management of abdominal septic shock in Italy. Blood Purif. 2011;32:331-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Qiu XH, Liu SQ, Guo FM, Yang Y, Qiu HB. [A meta-analysis of the effects of direct hemoperfusion with polymyxin B-immobilized fiber on prognosis in severe sepsis]. Zhonghua Neike Zazhi. 2011;50:316-321. [PubMed] |

| 44. | Sakurai J, Nagahama M, Oda M. Clostridium perfringens alpha-toxin: characterization and mode of action. J Biochem. 2004;136:569-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Oda M, Kabura M, Takagishi T, Suzue A, Tominaga K, Urano S, Nagahama M, Kobayashi K, Furukawa K, Furukawa K. Clostridium perfringens alpha-toxin recognizes the GM1a-TrkA complex. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:33070-33079. [PubMed] |

| 46. | Ochi S, Oda M, Nagahama M, Sakurai J. Clostridium perfringens alpha-toxin-induced hemolysis of horse erythrocytes is dependent on Ca2+ uptake. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1613:79-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Shah M, Bishburg E, Baran DA, Chan T. Epidemiology and outcomes of clostridial bacteremia at a tertiary-care institution. ScientificWorldJournal. 2009;9:144-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Stevens DL, Maier KA, Mitten JE. Effect of antibiotics on toxin production and viability of Clostridium perfringens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31:213-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Oda M, Kihara A, Yoshioka H, Saito Y, Watanabe N, Uoo K, Higashihara M, Nagahama M, Koide N, Yokochi T. Effect of erythromycin on biological activities induced by clostridium perfringens alpha-toxin. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;327:934-940. [PubMed] |

| 50. | Nagahama M, Oda M, Kobayashi K, Ochi S, Takagishi T, Shibutani M, Sakurai J. A recombinant carboxy-terminal domain of alpha-toxin protects mice against Clostridium perfringens. Microbiol Immunol. 2013;57:340-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Han SH. Review of hepatic abscess from Klebsiella pneumoniae. An association with diabetes mellitus and septic endophthalmitis. West J Med. 1995;162:220-224. [PubMed] |

| 52. | Kasai K, Manabe N, Tateishi K, Ichihara N, Ohta Y and Fujimoto C. Severe infections in diabetic patients of reported 568 cases in Japan. Proceedings Kagawa Prefectural College Health Sciences. 1999;1:1-10. |

| 53. | Kurai D, Araki K, Ishii H, Wada H, Saraya T, Yokoyama T, Watanabe M, Takada S, Koide T, Tamura H, Nagatomo S, Nakamoto K, Nakajima A, Makamura M, Honda K, Inui T, Goto H, Analysis of cases who were positive for Clostridium in blood culture. J Jpn Association Infect Dis. 2011;85 Supple 334. |

| 54. | Ngo JT, Parkins MD, Gregson DB, Pitout JD, Ross T, Church DL, Laupland KB. Population-based assessment of the incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of anaerobic bloodstream infections. Infection. 2013;41:41-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Zahar JR, Farhat H, Chachaty E, Meshaka P, Antoun S, Nitenberg G. Incidence and clinical significance of anaerobic bacteraemia in cancer patients: a 6-year retrospective study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2005;11:724-729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Woo PC, Lau SK, Chan KM, Fung AM, Tang BS, Yuen KY. Clostridium bacteraemia characterised by 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:301-307. [PubMed] |