Published online Jun 15, 2012. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v3.i6.123

Revised: May 27, 2012

Accepted: June 10, 2012

Published online: June 15, 2012

AIM: To examine the possible association between gastrointestinal symptoms and anxiety and depression in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

METHODS: The study was a matched case-control study based on a face to face interview with designed diagnostic screening questionnaires for gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms and T2DM, Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) for depression and General Anxiety Disorders (GAD-7) for anxiety. The questionnaire consisted of questions about symptoms and signs of anxiety and depression disorders. Also, socio-demographic characteristics, life style habits and the family history of patients were collected. It was carried out from June 2010 to May 2011 among Qatari and other Arab nationals over 20 years of age at Primary Health Care Centers of the Supreme Council of Health, Qatar, including patients with diabetes mellitus and healthy subjects over 20 years of age.

RESULTS: In the studied sample, most of the studied T2DM patients with GI symptoms (39.3%) and healthy subjects (33.3%) were in the age group 45-54 years (P < 0.001). The prevalence of severe depression (9.5% vs 4.4%, P < 0.001) and anxiety (26.3% vs 13.7%, P < 0.001) was significantly higher in T2DM patients with GI symptoms than in general population. Obesity (35.7% vs 31.2%) and being overweight (47.9% vs 42.8%) were significantly higher in T2DM patients with GI symptoms than in healthy subjects (P = 0.001). Mental health severity score was higher in T2DM patients with GI symptoms than in healthy subjects; depression (8.2 ± 3.7 vs 6.0 ± 3.6) and anxiety (7.6 ± 3.3 vs 6.0 ± 3.7). The most significant GI symptom which was considerably different from controls was early satiety [odds ratio (OR) = 10.8, P = 0.009] in depressed T2DM patients and loose/watery stools (OR = 2.79, P = 0.029) for severe anxiety. Anxiety was observed more than depression in T2DM patients with GI symptoms.

CONCLUSION: Gastrointestinal symptoms were significantly associated with depression and anxiety in T2DM patients, especially anxiety disorders.

- Citation: Bener A, Ghuloum S, Al-Hamaq AO, Dafeeah EE. Association between psychological distress and gastrointestinal symptoms in diabetes mellitus. World J Diabetes 2012; 3(6): 123-129

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v3/i6/123.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v3.i6.123

Gastrointestinal (GI) diseases are common worldwide. Although GI symptoms are very common in the general population, recent studies reported that GI complaints are commonly reported by diabetic patients, when compared with non-diabetic controls[1]. GI disturbances commonly include symptoms of stomach pain, heart burn, diarrhea, constipation, nausea and vomiting. Koch et al[2] indicated that complications involving the GI tract occur frequently and represent a major cause of morbidity in diabetes mellitus (DM). Although GI symptoms are not life threatening, the majority of those affected will cause significant burden to the health care system as well as reduced quality of life[3]. A study in Germany documented that GI symptoms were more frequent in patients with DM compared with controls[4]. Previous studies by Bener et al[5,6] stated that DM is becoming increasingly common because of the epidemic of obesity and sedentary lifestyles in the Qatar. A more recent study[7] revealed that the prevalence rate of GI disorders is high in the general community and there is a significant association with psychological disorders. But, no study has yet been conducted in Qatar to determine the prevalence of GI symptoms among the diabetic population. It is important to investigate the prevalence of GI symptoms in the diabetic population because GI symptoms affect quality of life adversely and represent a substantial cause of morbidity in patients with diabetes.

In general, GI symptoms are influenced by psychological factors such as depression and anxiety. Talley et al[8] indicated that diabetic patients with anxiety and depression had a two fold higher prevalence of GI symptoms. Moreover, a case-control study[9] in Qatar of the prevalence of psychological distress in diabetic patients showed that depression and anxiety were severe in diabetes, which is two fold higher than in non-diabetics. The three studies revealing the high prevalence of GI symptoms in general community and its association with psychological disorders and the severity of depression and anxiety in diabetics initiated the authors to examine whether these GI symptoms are more frequent in diabetic patients and to assess the association of GI symptoms with the psychological disorders. Investigation of a possible association between psychological distress and GI symptoms in diabetics has been extremely limited. The combination of psychological disorders and diabetes is common and especially harmful because it has a strong impact on psychosocial as well as medical outcomes in patients with diabetes[10]. Also, the gastrointestinal disturbances in diabetes may result from psychiatric morbidity.

In the Middle East region, we have found no studies examining the prevalence of GI symptoms and its association with psychological disorders in the diabetic population. This is the first study in Qatar investigating the prevalence of GI symptoms among the type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients, as well as their psychosocial impact.

This is a matched case-control study performed at the primary health care centers. The survey was conducted among the population residing in the Qatar from June 2010 to May 2011. Primary health care centers are frequented by all levels of the general population as a gateway to specialized care. The study was approved by the Hamad General Hospital, Hamad Medical Corporation. All human studies have been approved by the Research Ethics Committee and performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

T2DM is a major chronic disease with high morbidity and mortality in Qatar[9-11] and it is considered to be on the verge of an emerging diabetes epidemic. The power calculation was actually based on a reported prevalence rate of T2DM of 16.7%[6], allowing an error of 5%, level of significance (type-1 error) of 1% and with 95% confidence limits. It was computed that 453 cases and 453 controls as a sample size were needed to achieve the objective of our study. Of the 22 primary health care centers available, we selected 12 health centers at random. Of these, 9 were located in urban and three in semi-urban areas of Qatar. Finally, subjects were selected systematically 1-in-2 using a systematic sampling procedure. Each participant was provided with brief information about the study and was assured of strict confidentiality. The study excluded patients who were under 20 and over 65 years, patients with any cognitive or physical impairment and who refused to give consent to take part in the study.

The diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance was based on the criteria by the American Diabetes Association[12]. Subjects reporting a history of DM and currently taking oral medications for diabetes were considered to have DM. DM was defined according to the World Health Organization Expert Committee group[13], i.e. fasting venous blood glucose concentration ≥ 7.0 mmol/L and/or 2 h post-glucose meter and an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) venous blood glucose concentration ≥ 11.1 mmol/L. In all subjects, fasting blood glucose determined by OGTT was conducted only if blood sugar was < 7 mmol/L. For the OGTT, subjects were requested to drink, within the space of 5 min, 75 g anhydrous glucose dissolved in 250 mL water. Samples were processed within 30 min of collection and the above laboratory tests were measured. A total number of 625 T2DM patients aged over 20 years were selected systematically 1-in-2 using a systematic sampling procedure of the Primary Health Care (PHC) centers and 453 cases agreed to participate in the study, with a response rate of 72.5%.

Control subjects aged over 20 years were identified from the community as healthy if their venous blood glucose values were < 6.1 mmol/L and if they had never taken any diabetic medication. This group involved a random sample of 646 healthy subjects who visited the PHC centers for any reason other than acute or chronic disease. Of the 646 healthy subjects approached, 453 controls responded to our questionnaire, with a response rate of 70.1%. The healthy subjects were selected in a way to match the age and the gender of cases to give a good representative sample of the studied population.

The data were collected through validated self-administered questionnaires with the help of qualified nurses. The questionnaire had three sections. The first part included socio-demographic details, medical and family history, and dietary habits of patients. The second part included the most prevalent GI symptoms in primary care, like esophageal symptoms, upper dysmotility symptoms, constipation and diarrhea.

Depression was assessed with the eight-item depression module of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)[14]. Patients were asked to answer the questions by grading them from 0 to 3; with 0 for “not at all”, 1 for “several days”, 2 for “more than half of days” and 3 for “nearly every day”. Anxiety was assessed with the General Anxiety Disorders (GAD-7)[15]. Patients were asked to answer the questions by grading them from 0 to 3; with 0 for “not at all”, 1 for “several days”, 2 for “more than half the days”, and 3 for “nearly every day”. PHQ-9 ≥15 represent severe symptoms of depression and GAD ≥ 11 represent severe symptoms of anxiety disorders. We used cut-off scores of ≥ 15 on PHQ-9 and cut-off score of ≥ 11 on GAD-7 because this threshold reflects severe levels of depression and anxiety. Content validity, face validity and reliability of the questionnaire were tested using 100 children. These tests demonstrated a high level of validity and high degree of repeatability (kappa = 0.86).

Student-t test was used to ascertain the significance of differences between mean values of two continuous variables and confirmed by non-parametric Mann-Whitney test. χ2 and Fisher’s exact test were performed to test for differences in proportions of categorical variables between two or more groups. Stepwise logistic regression analysis was used to predict potential confounders and order the importance of risk factors (determinant) for diabetic factors associated with GI symptoms. The level P < 0.05 was considered as the cut-off value for significance.

Table 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the studied T2DM patients with GI symptoms and healthy subjects. Most of the studied T2DM patients with GI symptoms (39.3%) and healthy subjects (33.3%) were in the age group 45-54 years (P < 0.001). The prevalence of severe depression (9.5% vs 4.4%, P < 0.001) and anxiety (26.3% vs 13.7%, P < 0.001) was significantly higher in T2DM patients with gastrointestinal symptoms compared to healthy subjects. Mental health severity score was higher in T2DM patients with GI symptoms than in healthy subjects; depression (8.2 ± 3.7 vs 6.0 ± 3.6) and anxiety (7.6 ± 3.3 vs 6.0 ± 3.7). A significant difference was observed in the age group between T2DM with GI symptoms and non-diabetic subjects (P < 0.001). Most of the studied subjects were married (83.9%), with secondary education (32.7%) and sedentary/professional jobs (30.4%).

| Variables | Totaln = 906 | Diabetic with GIn = 453 | Healthysubjectsn = 453 | P value |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 46.9 ± 10.3 | 49.0 ± 9.9 | 44.8 ± 10.2 | < 0.001 |

| Age group (yr) | ||||

| < 35 | 121 (13.4) | 37 (8.2) | 84 (18.5) | < 0.001 |

| 35-44 | 225 (24.8) | 101 (22.3) | 124 (27.4) | |

| 45-54 | 329 (36.3) | 178 (39.3) | 151 (33.3) | |

| ≥ 55 | 231 (25.5) | 137 (30.2) | 94 (20.8) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 544 (60.0) | 278 (61.4) | 266 (58.7) | 0.456 |

| Female | 362 (40.0) | 175 (38.6) | 187 (41.3) | |

| Nationality | ||||

| Qatari | 423 (46.7) | 200 (44.2) | 223 (49.2) | 0.143 |

| Non-Qatari | 483 (53.3) | 253 (55.8) | 230 (50.8) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 146 (16.1) | 62 (13.7) | 84 (18.5) | 0.058 |

| Married | 760 (83.9) | 391 (86.3) | 369 (81.5) | |

| Educational level | ||||

| Illiterate | 56 (6.2) | 32 (7.1) | 24 (5.3) | 0.329 |

| Primary | 114 (12.6) | 63 (13.9) | 51 (11.3) | |

| Intermediate | 182 (20.1) | 96 (21.2) | 86 (19.0) | |

| Secondary | 296 (32.7) | 139 (30.7) | 157 (34.7) | |

| University | 258 (28.5) | 123 (27.2) | 135 (29.8) | |

| Occupation | ||||

| Not working/housewife | 275 (30.4) | 132 (29.1) | 143 (31.6) | 0.564 |

| Sedentary/professional | 275 (30.4) | 138 (30.5) | 137 (30.2) | |

| Clerk/manual | 187 (20.6) | 90 (19.9) | 97 (21.4) | |

| Businessman | 106 (11.7) | 56 (12.4) | 50 (11.0) | |

| Army/police/security | 63 (7.0) | 37 (8.2) | 26 (5.7) | |

| Household income1 | ||||

| < 5000 | 71 (7.8) | 38 (8.4) | 33 (7.3) | 0.227 |

| 5000 – 9999 | 303 (33.4) | 147 (32.5) | 156 (34.4) | |

| 10 000 – 15 000 | 328 (36.2) | 176 (38.9) | 152 (33.6) | |

| > 15 000 | 204 (22.6) | 92 (20.3) | 112 (24.7) | |

| Mental health severity | ||||

| PHQ-9 depression (0–24) mean ± SD (95% CI) | 7.1 ± 3.8 | 8.2 ± 3.7 | 6.0 ± 3.7 | < 0.001 |

| (7.9-8.6) | (5.7-6.4) | |||

| GAD-7 anxiety (0-21) | 6.8 ± 3.6 | 7.6 ± 3.3 | 6.0 ± 3.7 | < 0.001 |

| mean ± SD (95% CI) | (7.3-7.9) | (5.7-6.4) | ||

| Comorbidity | ||||

| Severe depression (PHQ≥ 15) | 59 (6.5) | 43 (9.5) | 20 (4.4) | < 0.001 |

| Severe anxiety (GAD7≥ 11) | 169 (18.6) | 107 (23.6) | 62 (13.7) | < 0.001 |

| Frequency of GI symptoms | 389 (42.9) | 264 (58.3) | 217 (47.9) | 0.002 |

| (at least two or more symptoms) |

Table 2 shows the lifestyle habits and family history of studied T2DM patients with GI symptoms and healthy subjects. Obesity (35.7% vs 31.2%) and being overweight (47.9% vs 42.8%) were significantly higher in T2DM patients with GI symptoms compared to healthy subjects (P = 0.001). Compared with healthy subjects, physical activity was significantly less frequent in T2DM patients with GI symptoms (64.9% vs 43.9%, P < 0.001) and smoking was also higher in T2DM patients (30% vs 13.9 %, P = 0.001).

| Variables | Diabetic with GIn = 453 | Healthysubjectsn = 453 | P value |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| Normal (< 25) | 74 (16.3) | 118 (26.0) | |

| Overweight (25-30) | 217 (47.9) | 194 (42.8) | 0.001 |

| Obese (> 30) | 162 (35.7) | 141 (31.2) | |

| Physical activity | |||

| Yes1 | 159 (35.1) | 254 (56.1) | < 0.001 |

| No | 294 (64.9) | 199 (43.9) | |

| Smoking (Cigarette/sheesha) | |||

| Yes | 136 (30.0) | 63 (13.9) | 0.001 |

| No | 317 (70.0) | 390 (86.1) | |

| Dietary habits2 | |||

| Type of food | |||

| Arabic | 408 (90.1) | 402 (88.7) | 0.590 |

| Indian/Pakistani | 59 (13.0) | 87 (19.2) | 0.014 |

| Western | 24 (5.3) | 34 (7.5) | 0.222 |

| Type of oil | |||

| Vegetable oil | 302 (66.7) | 299 (66.0) | 0.833 |

| Olive oil | 248 (54.7) | 181 (40.0) | < 0.001 |

| Animal fat/butter | 104 (23.0) | 92 (20.3) | 0.334 |

| Pattern of daily food | |||

| Vegetable | 327 (72.2) | 242 (53.4) | < 0.001 |

| Fruit | 221 (48.8) | 144 (31.8) | < 0.001 |

| Red meat | 206 (45.5) | 256 (56.5) | 0.001 |

| Chicken | 240 (53.0) | 157 (34.7) | < 0.001 |

| Fish | 189 (41.7) | 113 (24.9) | < 0.001 |

| Type of drink | |||

| Arabic coffee | 342 (75.5) | 337 (74.4) | 0.759 |

| Turkish coffee | 55 (12.1) | 49 (10.8) | 0.602 |

| Nescafe | 170 (37.5) | 54 (11.9) | < 0.001 |

| Juice | 100 (22.1) | 78 (17.2) | 0.079 |

| Tea | 361 (79.7) | 367 (81.0) | 0.676 |

Table 3 presents the comparison of gastrointestinal symptoms between studied T2DM patients with GI symptoms and healthy subjects with severe anxiety and depression. The depression and anxiety were more prevalent in T2DM patients with most of the GI symptoms compared to healthy subjects. Compared to healthy subjects, the diabetic patients were more depressed with a significant difference with anal blockage (46.5% vs 20%, P = 0.050), heartburn (41.9% vs 15%, P = 0.046), < 3 bowels/wk (51.2% vs 20%, P = 0.028), > 3 bowels/d (48.8% vs 20%, P = 0.050), early satiety (41.9% vs 5%, P = 0.003) and fecal incontinence (37.2% vs 5%, P = 0.007). The diabetic patients were significantly more anxious with GI symptoms of anal blockage (53.3% vs 35.5%, P = 0.026), heartburn (34.6% vs 17.7%; P = 0.019), loose/watery stools (26.2% vs 11.3%, P = 0.021) and postprandial illness (26.2% vs 12.9%, P = 0.042).

| Variables | Severe anxiety1 | P value | Severe depression2 | P value | ||

| DM with GI | Healthy subjects | DM with GI | Healthy subjects | |||

| GI symptoms | n = 107 | n = 62 | n = 43 | n = 20 | ||

| Anal blockage | 57 (53.3) | 22 (35.5) | 0.026 | 20 (46.5) | 4 (20) | 0.050 |

| Bloating | 54 (50.5) | 25 (40.3) | 0.203 | 18 (41.9) | 6 (30) | 0.416 |

| Urgency | 54 (50.5) | 24 (38.7) | 0.139 | 17( 39.5) | 5 (25) | 0.395 |

| Vomiting | 37 (34.6) | 16 (25.8) | 0.236 | 18 (41.9) | 5 (25) | 0.264 |

| Dysphasia | 44 (41.1) | - | - | 26 (60.5) | - | |

| Nausea | 38 (35.5) | 19 (30.6) | 0.519 | 13 (30.2) | 6 (30) | 0.980 |

| Heartburn | 37 (34.6) | 11 (17.7) | 0.019 | 18 (41.9) | 3 (15) | 0.046 |

| < 3 bowels/wk | 36 (33.6) | 18 (29.0) | 0.805 | 22 (51.2) | 4 (20) | 0.028 |

| > 3 Bowels/d | 32 (29.9) | 18 (29.0) | 0.993 | 21 (48.8) | 4 (20) | 0.050 |

| Abdominal pain | 22 (20.6) | 16 (25.8) | 0.431 | 10 (23.3) | 5 (25) | 0.989 |

| Lumpy/hard stools | 30 (28.0) | 13 (21.0) | 0.309 | 13 (30.2) | 5 (25) | 0.770 |

| Blood in stool | 24 (22.4) | 19 (30.6) | 0.237 | 6 (14.0) | 5 (25) | 0.304 |

| Early satiety | 28 (26.2) | 17 (27.4) | 0.859 | 18 (41.9) | 1 (5) | 0.003 |

| Loose/watery stools | 28 (26.2) | 7 (11.3) | 0.021 | 10 (23.3) | 5 (25) | 0.989 |

| Fecal incontinence | 25 (23.4) | 17 (27.4) | 0.557 | 16 (37.2) | 1 (5) | 0.007 |

| Weight loss | 25 (23.4) | 10 (16.1) | 0.263 | 6 (14.0) | 6 (30) | 0.172 |

| Postprandial fullness | 28 (26.2) | 8 (12.9) | 0.042 | 7 (16.3) | 4 (20) | 0.732 |

Table 4 shows the extracted odd ratios and confidence intervals of GI symptoms on anxiety and depression with diabetic patients vs healthy subjects. The diabetic patients with severe anxiety were significantly more different from the healthy subjects in loose/watery stools (OR = 2.79, P = 0.029), heartburn (OR = 2.45, P = 0.022), postprandial fullness (OR = 2.39, P = 0.042), anal blockage (OR = 2.07 P = 0.026) and dysphasia (OR = 1.98; P < 0.001). Similarly, diabetic depressed patients were also significantly different from non-diabetic subjects in early satiety (OR = 10.8; P = 0.009), fecal incontinence (OR =8.89; P = 0.024), heartburn (OR = 5.04; P = 0.036), < 3 bowels/wk (OR = 4.54; P = 0.038), > 3 bowels/d (OR = 4.14; P = 0.043) and anal blockage (OR = 3.77; P = 0.05).

| GI symptoms | OR | 95% CI | P value |

| Anxiety | |||

| Loose/watery stools | 2.79 | (1.14-6.83) | 0.029 |

| Heartburn | 2.45 | (1.14-5.26) | 0.022 |

| Postprandial fullness | 2.39 | (1.01-5.65) | 0.042 |

| Anal blockage | 2.07 | (1.10-3.95) | 0.026 |

| Dysphasia | 1.98 | (1.67-2.36) | < 0.001 |

| Depression | |||

| Early satiety | 10.8 | (1.30-89.34) | 0.009 |

| Fecal incontinence | 8.89 | (1.07-73.8) | 0.024 |

| Heartburn | 5.04 | (1.02-24.98) | 0.036 |

| < 3 bowels/wk | 4.54 | (1.13-18.26) | 0.038 |

| > 3 Bowels/d | 4.14 | (1.03-16.6) | 0.043 |

| Anal blockage | 3.77 | (0.94-15.41) | 0.050 |

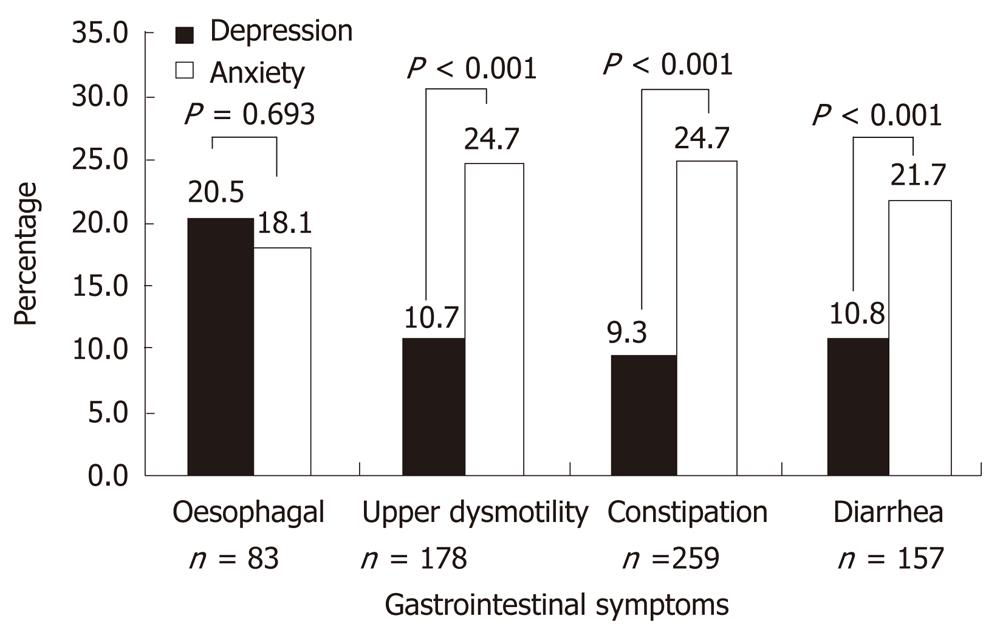

Figure 1 reveals the distribution of severe levels of depression and anxiety in diabetic patients with GI symptoms. The prevalence of anxiety was observed more in diabetic patients with GI symptoms; upper dysmotility (24.7% vs 10.7%, P < 0.001), constipation (24.7% vs 9.3%, P < 0.001) and diarrhea (21.7% vs 10.8%, P < 0.001), while depression was higher in esophageal symptoms (20.5% vs 18.1%).

Gastrointestinal symptoms are reportedly common in diabetic patients and symptoms are also frequent in individuals without DM. Therefore, this study determined whether these GI symptoms are more frequent in the diabetic population of Qatar and also assessed the association between GI disorders and psychological distress. The potential association between GI symptoms and psychological distress in diabetes has not been studied in this region. It is important to assess the effect of GI symptoms on the psychological profile for individual symptoms in diabetic patients because the co-occurrences of psychological disorders and gastrointestinal symptoms contribute to a high medical utilization in primary health care settings. Co-morbidity seems to play an essential role in increasing symptoms. The study detected higher levels of gastrointestinal symptoms in the diabetic population with depression and anxiety compared to the general population. However, patients with diabetes are almost twice as likely to suffer from anxiety and depression than the general population[16].

In the study sample, the prevalence of severe depression (9.5% vs 4.4%, P < 0.001) and anxiety (26.3% vs 13.7%) was significantly higher in diabetic patients than in the healthy population. Koloski et al[17] reported that psychological distress is linked to having persistent GI symptoms and frequently seeking health care. More than half of the diabetic patients (58.3%) evaluated reported at least two or more troublesome GI symptoms, which is very close to the figure reported in a study by Talley et al[18] (40%), with a significant difference with the healthy subjects. An increased prevalence of GI symptoms in patients with diabetes was reported in the study sample which is in agreement with previous studies[1,19]. In a Chinese diabetic population[20], it was found that 70% of them had GI symptoms which was much higher than in their non-diabetic controls. The difference in GI symptoms prevalence among studies depends on the specific diabetic population. The majority of the diabetic patients (39.3%) with gastrointestinal symptoms were observed in the age group 45-54 years.

In our diabetic population, patients were more depressed with the GI symptoms of anal blockage (46.5% vs 20.0%), heartburn (41.9% vs 12.5%), < 3 bowels/wk (51.2% vs 18.8%), > 3 bowels/d (48.8% vs 20.0%), early satiety (41.9% vs 5%) and fecal incontinence (37.2% vs 5%) compared to healthy subjects. In a study by Kolaski et al[17], it was found that increased levels of psychological distress were associated with persistent GI symptoms, in particular abdominal pain, constipation and bloating, which is similar to our study results. De Kort et al[21] indicated that GI symptoms were considerably higher in the diabetic population with 17.9% for diarrhea, 16.1% for constipation, 19.6% for bloating and 12.5% for early satiety. Bytzer et al[19] showed an increased prevalence of diarrhea or constipation (15.6%), bloating (12.3%) and early satiety (54%) in diabetic patients. Even the odd ratios revealed that early satiety (OR = 10.8), fecal incontinence (OR = 8.89), heartburn (OR = 5.04), < 3 bowels/wk (OR = 4.54), > 3 bowels/d (OR = 4.14) and anal blockage (OR = 3.77) were significantly different in diabetic depressed patients from healthy subjects. These data show that gastrointestinal symptoms were more closely related to psychiatric disturbances. On the other hand, it is also possible that unpleasant GI symptoms lead to increased anxiety and depression.

Even so, the studied diabetic patients were significantly more anxious with the GI symptoms of anal blockage (53.3% vs 35.5%), heartburn (34.6% vs 17.7%), loose/watery stools (26.2% vs 11.3%) and postprandial illness (26.2% vs 12.9%) and they were significantly different from their counterparts. It is documented that psychological vulnerability is associated with a poorer outcome for people with chronic GI symptoms[22]. In studied diabetic patients with severe anxiety, odd ratios revealed that loose/watery stools (OR = 2.79), heart burn (OR = 2.45), postprandial fullness (OR = 2.39), anal blockage (OR = 2.07) and dysphasia (OR = 1.98) symptoms remained significantly different from healthy subjects. Odd ratios reported in a study revealed that suffering diabetes was associated with suffering a mental disorder[23]. Gastrointestinal symptoms negatively affect health related quality of life in diabetes and clinicians should consider psychological factors in the treatment of GI symptoms.

The study findings show that psychological distress may be one important underlying component of the condition and should be considered by physicians in their treatment of patients. One study suggests that physicians could usefully explore the fear and anxiety of patients about their symptoms to reduce subsequent health care seeking[24]. In our diabetic population, psychological factors seem to affect GI symptoms to a large extent and should be taken into account when considering treatment of these symptoms. The current high prevalence of type 2 diabetes is likely to result in a heavy burden of diabetes complications; this will pose a significant challenge to individuals, communities and health care systems during the coming decades.

The study findings revealed that all GI symptoms occur frequently in diabetic patients compared with community controls. Also, GI symptoms in diabetes are strongly linked to depression and anxiety. The study has observed a significantly increased prevalence of the GI symptoms like anal blockage, heartburn, < 3 bowel/wk, < 3 bowels/d and fecal incontinence in depressed diabetic patients compared to healthy subjects. Anxiety, loose/watery stools, heartburn, postprandial fullness, anal blockage and dysphasia were significantly different from controls. Further studies are recommended to clarify the potential causal relationship between GI symptoms and psychological factors in diabetes.

The authors would like to thank the Hamad Medical Corporation for their support and ethical approval (ref: RP#7100/07).

Gastrointestinal symptoms are reportedly more common in diabetic patients. Little is known about the natural history of gastrointestinal symptoms and what factors influence gastrointestinal (GI) symptom patterns in diabetic patients. So this study aimed to examine the possible association between gastrointestinal symptoms with anxiety and depression in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

The prevalence of diabetes mellitus and its complications are high in the community. The study highlighted the importance of establishing a disease registry on diabetes mellitus and follow up screening for their complications.

In the present study, the authors report the high occurrence of GI symptoms in diabetic patients compared to the healthy subjects. Also, the study observed a high prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms in diabetic patients with depression and anxiety. The important study findings of the present article were compared with similar studies so as to allow the readers to understand the situation and major points related to the topic.

The study recommended further studies to clarify the potential relationship between GI symptoms and psychological factors in diabetes.

In this study, the authors attempted to identify the association of psychological distress and gastrointestinal symptoms in T2DM patients. The study suggests that physicians should consider psychological factors in the treatment of GI symptoms in diabetic patients. Readers can understand that the gastrointestinal symptoms affect health related quality of life in diabetes.

Peer reviewers: Dr. Patti L Darbishire, Department of Pharmacy Practice, Purdue University, 575 Stadium Mall Drive, Heine Pharmacy 304A, West Lafayette, IN 47907, United States; Dr. Michael Kluge, Department of Psychiatry, University of Leipzig, Semmelweisstrasse 10, Leipzig 04103, Germany

S- Editor Wu X L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Wu X

| 1. | Ricci JA, Siddique R, Stewart WF, Sandler RS, Sloan S, Farup CE. Upper gastrointestinal symptoms in a U.S. national sample of adults with diabetes. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:152-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Koch KL. Diabetic gastropathy: gastric neuromuscular dysfunction in diabetes mellitus: a review of symptoms, pathophysiology, and treatment. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:1061-1075. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Koloski NA, Talley NJ, Boyce PM. The impact of functional gastrointestinal disorders on quality of life. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:67-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Enck P, Rathmann W, Spiekermann M, Czerner D, Tschöpe D, Ziegler D, Strohmeyer G, Gries FA. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms in diabetic patients and non-diabetic subjects. Z Gastroenterol. 1994;32:637-641. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Bener A, Zirie M, Janahi IM, Al-Hamaq AO, Musallam M, Wareham NJ. Prevalence of diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes mellitus and its risk factors in a population-based study of Qatar. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2009;84:99-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bener A, Zirie M, Musallam M, Khader YS, Al-Hamaq AO. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome according to Adult Treatment Panel III and International Diabetes Federation criteria: a population-based study. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2009;7:221-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bener A, Dafeeah EE. Impact of Depression and Anxiety Disorders on Gastrointestinal Symptoms and its Prevalence in the General Population. J Mens health. 2010;7:294. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Talley SJ, Bytzer P, Hammer J, Young L, Jones M, Horowitz M. Psychological distress is linked to gastrointestinal symptoms in diabetes mellitus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1033-1038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bener A, Al-Hamaq AOAA, Dafeeah EE. High Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety and Stress Syptoms among Diabetes Mellitus Patients. Open Psychiatr J. 2011;5:5-12. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Collins MM, Corcoran P, Perry IJ. Anxiety and depression symptoms in patients with diabetes. Diabet Med. 2009;26:153-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 281] [Cited by in RCA: 295] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bener A, Kamal A, Fares A, Sabuncuoglu O. The prospective study of anxiety, depression and stress on development of hypertension. Arab J Psychiatr. 2004;15:131-136. |

| 12. | American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2008;31 Suppl 1:S55-S60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 692] [Cited by in RCA: 721] [Article Influence: 42.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Genuth S, Alberti KG, Bennett P, Buse J, Defronzo R, Kahn R, Kitzmiller J, Knowler WC, Lebovitz H, Lernmark A. Follow-up report on the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:3160-3167. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21545] [Cited by in RCA: 28948] [Article Influence: 1206.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-1097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11947] [Cited by in RCA: 18884] [Article Influence: 993.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Egede LE, Zheng D, Simpson K. Comorbid depression is associated with increased health care use and expenditures in individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:464-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 519] [Cited by in RCA: 520] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Koloski NA, Talley NJ, Boyce PM. Does psychological distress modulate functional gastrointestinal symptoms and health care seeking? A prospective, community Cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:789-797. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ. Irritable bowel syndrome in a community: symptom subgroups, risk factors, and health care utilization. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:76-83. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Bytzer P, Talley NJ, Hammer J, Young LJ, Jones MP, Horowitz M. GI symptoms in diabetes mellitus are associated with both poor glycemic control and diabetic complications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:604-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ko GT, Chan WB, Chan JC, Tsang LW, Cockram CS. Gastrointestinal symptoms in Chinese patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 1999;16:670-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | de Kort S, Kruimel JW, Sels JP, Arts IC, Schaper NC, Masclee AA. Gastrointestinal symptoms in diabetes mellitus, and their relation to anxiety and depression. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;96:248-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Whitehead WE, Crowell MD, Robinson JC, Heller BR, Schuster MM. Effects of stressful life events on bowel symptoms: subjects with irritable bowel syndrome compared with subjects without bowel dysfunction. Gut. 1992;33:825-830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 294] [Cited by in RCA: 291] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Jimenez-Garcıa R, Martinez Huedo MA, Hernandez-Barrera V, de Andres AL, Martinez D, Jimenez-Trujillo I, Carrasco-Garrido P. Psychological distress and mental disorders among Spanish diabetic adults: A case-control study. Prim Care Diabetes. 2012;6:149-156. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Owens DM, Nelson DK, Talley NJ. The irritable bowel syndrome: long-term prognosis and the physician-patient interaction. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:107-112. [PubMed] |