Published online Aug 15, 2025. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v16.i8.106927

Revised: May 4, 2025

Accepted: June 24, 2025

Published online: August 15, 2025

Processing time: 156 Days and 11.9 Hours

Social determinants of health are social and economic factors that influence health intervention outcomes. Type 2 diabetes is a highly prevalent disease, primarily affecting individuals in low-to-middle-income countries. However, the association between social determinants and cardiovascular complications in type 2 diabetes has not been widely studied.

To examine the relationship between social determinants of health and car

We conducted a retrospective cohort study with an analytical component at a national-level referral hospital for military personnel in Bogota, Colombia. Patients treated at the diabetes clinic between September 2021 and December 2022 who met the inclusion criteria were included. A total of 583 patients participated in the study. We performed descriptive, bivariate, and binary logistic regression analyses, adjusting for confounding variables.

Among the 583 patients included, urban residency [odds ratio (OR) = 3.05, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.01-9.20] and a middle or high educational level (OR = 2.33, 95%CI: 1.14-4.72) were associated with an increased risk of coronary artery disease. Additionally, receiving diabetes education beyond that provided by the clinic (OR = 2.15, 95%CI: 1.14-4.05) and lack of access to spaces for physical activity (OR = 4.05, 95%CI: 1.31-12.5) were associated with a higher risk of diabetic nephropathy and cerebrovascular disease, respectively.

Programs for diabetes management should account for social determinants of health that contribute to cardiovascular complications and increased healthcare costs. Population-based studies are needed to guide targeted interventions and clarify causal relationships.

Core Tip: Cardiac complications related to type 2 diabetes are affected by the condition of the patient and social determinants of health. These cardiovascular complications result in a lower quality of life and a more significant economic burden on health systems. Among the social determinants of health analyzed, urban residents and those with a middle or high educational level showed a higher risk of coronary artery disease. Receiving additional education beyond that provided by the diabetes clinic and individuals without the availability of spaces for physical activity showed a higher risk of developing diabetes nephropathy and cerebrovascular disease.

- Citation: Rincon O, Uscategui C, Mancera P, Luna M, Rodriguez A, Alvarez M, Guzman I. Association of social determinants of health and cardiovascular complications in type 2 diabetes in Colombia. World J Diabetes 2025; 16(8): 106927

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v16/i8/106927.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v16.i8.106927

Diabetes is a highly prevalent disease, with an estimated 537 million people worldwide living with diabetes. Type 2 diabetes is the most common presentation, accounting for more than 90% of all cases[1]. In low-income and middle-income countries, the prevalence is even higher, with an estimated three out of every four people diagnosed with diabetes living in these regions. The prevalence is higher in urban regions compared with rural regions (12.1% vs 8.1%)[1]. In the Central and South American regions, the prevalence of diabetes is close to 8.2% of the population. In Colombia, experts estimate that diabetes affects between 7% to 9%[1].

The World Health Organization defines social determinants as “Non-medical factors that influence health outcomes, they are the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems that shape the conditions of daily life”[2]. The deleterious impact of suboptimal social conditions transcends the ability of individuals to adapt, resulting in altered cortisol levels and epigenetic and cell adaptations that lead to adverse health outcomes that affect both individual and future generations[3,4]. Previous studies have linked social differences among the most disadvantaged groups with excess mortality from any cause, cardiovascular mortality, and non-cardiovascular, nononcological death, with 72% of deaths attributable to social determinants[5].

Type 2 diabetes is associated with multiple macrovascular complications such as coronary artery disease, cere

As of 2022 the United Nations and World Bank reported that Colombia was 91st in the human development index, with a 0.758. A life expectancy of 73 years, 8.9 years as the average educational period, and a per capita income of 15.014 (constant 2017 purchasing power parity). However, due to socioeconomic disparities in the country, the human development index falls to 0.56 when adjusted for inequality, resulting in a loss of 25% in human development[7]. The Gini index measures 0.548 for income inequality, leaving Colombia in the third place in the world[8] and 0.75 for the gender gap index, making Colombia 42nd among 146 countries. Both indices exhibit great difficulties for females, especially in the areas of empowerment and labor market[9].

The relationship between social determinants of health and cardiovascular complications in patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes has not been subject to extensive evaluation. Previous studies have documented the association between a small support network and a low percentage of friends with macrovascular complications[10], and the lack of spaces for physical activity among people with low socioeconomic status is associated with a higher presence of macrovascular and microvascular complications[11]. The present study investigated the possible association between social determinants, namely socioeconomic status, educational level, economic income, availability of physical activity spaces, and diabetes education received outside of the care program, with cardiovascular complications (macrovascular and microvascular) resulting from the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. Although this study does not allow for causal inference, it may indicate potential associations between social determinants of health and microvascular and macrovascular complications in individuals with type 2 diabetes.

This retrospective cohort study with an analytical component was conducted among individuals aged 18 years and older who had been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes and received treatment through the diabetes clinic program at a referral center serving the military health system population in Bogota, Colombia. The study was based on electronic medical records of patients who received care between September 2021 and December 2022.

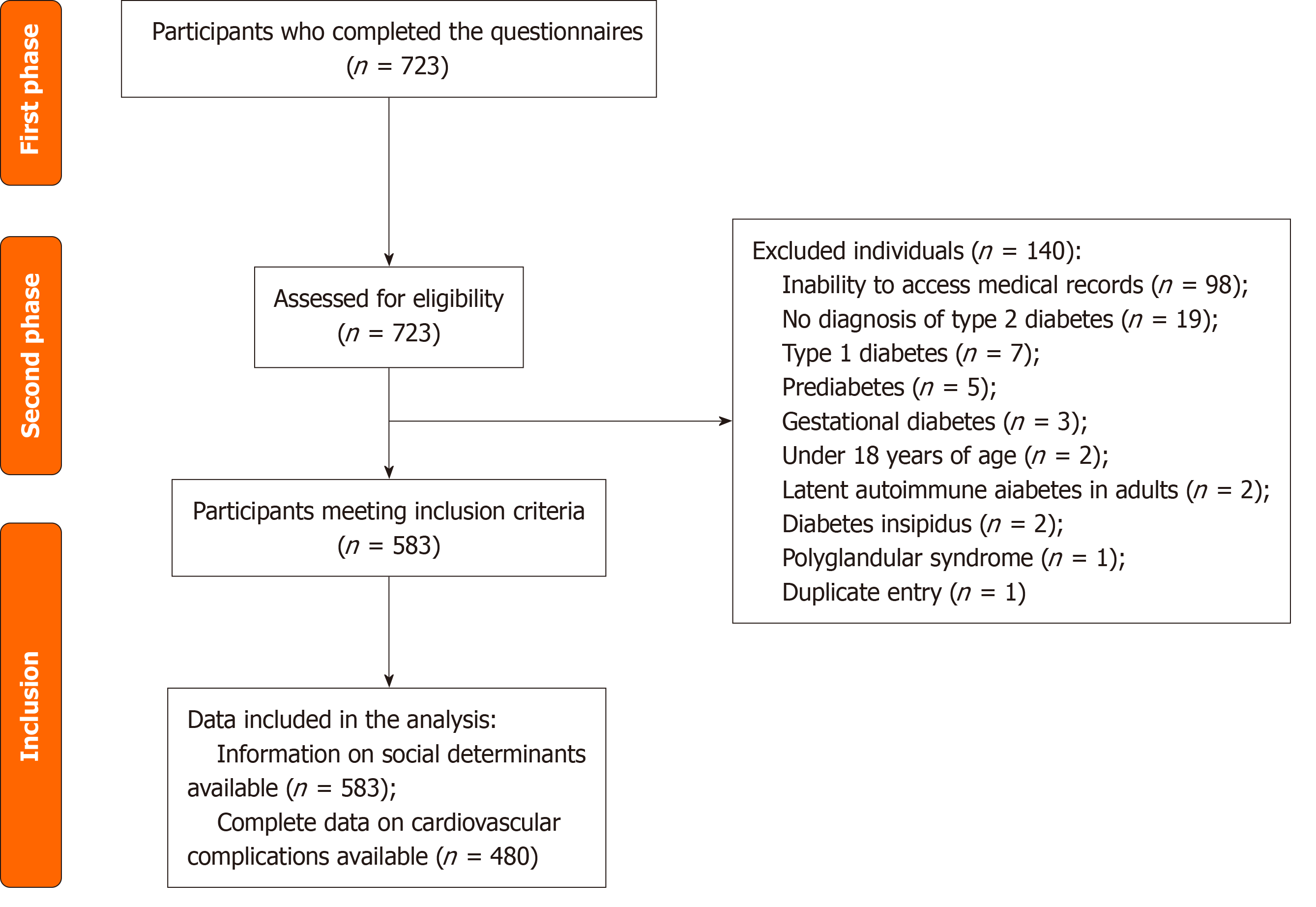

Data collection was conducted in two phases. The first phase involved a structured interview assessing patients’ social environments, including area of residence, history of forced displacement, level of education, socioeconomic stratum, monthly income, marital status, presence of a caregiver, additional diabetes education beyond that provided by the clinic, and availability of spaces for physical activity. The second phase involved extracting clinical data from electronic medical records, including anthropometric measurements from the most recent consultation and biochemical parameters from the latest evaluation: Glycated hemoglobin; total cholesterol; low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C); triglycerides; duration of type 2 diabetes; smoking history; and the presence of macrovascular (coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, and peripheral arterial disease) and microvascular (diabetic re

The primary objective of this study was to conduct an exploratory analysis to assess potential associations between social determinants of health and cardiovascular complications, including macrovascular and microvascular complications. Secondary objectives included evaluating sex-stratified differences in anthropometric and biochemical characteristics, social determinants, and cardiovascular outcomes. As the entire eligible population was included, no sample size calculation was required. A descriptive analysis of the study population was performed, stratified by sex. Quantitative variables were assessed for normality; non-normally distributed variables were reported as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs), while categorical variables were presented as absolute and relative frequencies n (%). The prevalence of macrovascular and microvascular complications was also stratified by sex.

Associations between social determinants (independent variables) and cardiovascular complications (dependent variables) were examined using a binary logistic regression model, adjusting for potential confounders including age, duration of type 2 diabetes, smoking history, and body mass index (BMI), based on their established relationship with diabetes-related outcomes. Missing data were not imputed. All statistical analyses were conducted using R, an open-source statistical software[12].

A total of 583 individuals completed the sociodemographic characteristics questionnaire, of whom 49% were female. The median age of the cohort was 72 years (IQR: 60-80), and the median duration since diabetes diagnosis was 9 years (IQR: 3-16). The median BMI was 26 kg/m2 (IQR: 23-30). In the biochemical evaluation the median glycated hemoglobin level was 7.3% (IQR: 6.2-9.0), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol was 82 mg/dL (IQR: 59-115), HDL-C was 40 mg/dL (IQR: 32-49), and triglycerides were 143 mg/dL (IQR: 107-200). HDL-C and triglyceride levels were significantly higher in females than in males (P < 0.01) (Table 1).

| Variable | n | Females, n = 288 | Males, n = 295 | Total, n = 583 |

| Age, years | 560 | 73 (62-80) | 70 (58-80) | 72 (60-80) |

| Weight, kg | 469 | 67 (58-79) | 73 (65-81)a | 70 (60-80) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 462 | 26 (23-32) | 26 (23-28) | 26 (23-30) |

| Disease duration, years | 480 | 8.0 (2.0-15.8) | 10.0 (3.0-17.0) | 9.0 (3.0-16.0) |

| SBP, mmHg | 483 | 130 (120-146) | 132 (120-146) | 131 (120-146) |

| HbA1c (%) | 425 | 7.3 (6.2-9.2) | 7.4 (6.2-8.9) | 7.3 (6.2-9.0) |

| Total-C, mg/dL | 278 | 166 (121-190) | 143 (117-188) | 156 (119-190) |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | 245 | 92 (65-111) | 78 (54-121) | 82 (59-115) |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 244 | 42 (32-52)a | 37 (31-45) | 40 (32-49) |

| TG, mg/dL | 267 | 155 (117-212)1 | 132 (100-191) | 143 (107-200) |

A total of 85% of participants resided in urban areas. Based on socioeconomic classification the majority of the population belonged to the middle socioeconomic stratum (62%), followed by the low (31%) and high (7%) strata. Educational attainment was distributed as follows: Secondary education (33%); primary education (32%); professional degree (17%); technical training (15%); and no formal education (3%). A significant difference was observed between genders, with 25% of males having professional degrees compared with 9% of females (P < 0.001). Marital status also differed significantly by sex, with males more frequently married (71% vs 35%, P < 0.01), while females were more likely to be widowed (42% vs 12%, P < 0.01).

Regarding income, 44% of the population reported earning between 2 and 3 times the minimum wage. Females were more likely than males to earn one or less times the minimum wage (46% vs 17%, P < 0.01), whereas males were more likely to earn between 2 and 3 times the minimum wage (49% vs 40%, P < 0.01). Additionally, 36% of participants had a primary caregiver, with females more likely than males to have one (41% vs 31%, P = 0.018). Only 29% of the population reported having access to spaces for physical activity (Table 2).

| Variable | Females, n = 288 | Males, n = 295 | Total, n = 583 |

| Place of residence (rural) | 44 (15) | 43 (15) | 87 (15) |

| Forced displacement1 (yes) | 38 (13) | 27 (9) | 65 (11) |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 45 (16) | 27 (9) | 72 (12) |

| Married | 102 (35) | 210 (71)a | 312 (52) |

| Common-law | 21 (7) | 23 (8) | 44 (7) |

| Widowed | 120 (42)a | 34 (12) | 154 (26) |

| Monthly income per person, NMW2 | |||

| 0-1 | 132 (46)a | 50 (17) | 182 (31) |

| 45691 | 114 (40) | 141 (48)a | 255 (44) |

| 45753 | 21 (7) | 70 (24) | 91 (16) |

| > 6 | 15 (5) | 26 (9) | 41 (7) |

| Socioeconomic stratum | |||

| Low | 98 (34) | 83 (28) | 181 (31) |

| Medium | 173 (60) | 183 (62) | 359 (61) |

| High | 16 (6) | 24 (8) | 40 (7) |

| Educational level | |||

| None | 12 (4) | 8 (3) | 20 (3) |

| Primary | 120 (42)a | 64 (22) | 184 (32) |

| Secondary | 92 (32) | 98 (33) | 190 (33) |

| Technical | 38 (13) | 51 (17) | 89 (15) |

| Professional | 25 (9) | 72 (24)a | 97 (17) |

| Has caregiver (yes) | 117 (41)a | 90 (31) | 207 (36) |

| Availability of physical activity spaces (no) | 97 (34)a | 64 (22) | 161 (28) |

| Additional diabetes education (yes) | 75 (26) | 96 (33) | 171 (29) |

Among diabetes-related complications, coronary artery disease (26%) and diabetic nephropathy (24%) were the most prevalent. Compared with females, males had a significantly higher prevalence of coronary artery disease (31% vs 19%, P = 0.03), peripheral arterial disease (11% vs 6%, P = 0.04), and diabetic nephropathy (28% vs 19%, P = 0.02) (Table 3).

| Variable | Females, n = 233 | Males, n = 247 | Total, n = 480 |

| Coronary artery disease | 46 (20) | 78 (32)a | 124 (26) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 19 (8) | 12 (5) | 31 (6) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 13 (6) | 26 (11)a | 39 (8) |

| Diabetic retinopathy | 14 (6) | 24 (10) | 38 (8) |

| Diabetic retinopathy | 17 (7) | 25 (10) | 42 (9) |

| Diabetic nephropathy | 45 (19) | 69 (28)a | 114 (24) |

Social determinants that showed significant differences in the bivariate analyses with glycemic control and cardiovascular risk measures were included as explanatory variables in simple binomial logistic regression models. These models were adjusted for potential confounders, including smoking history, duration of diabetes, and BMI, to identify which variables were independently associated with macrovascular and microvascular complications. Urban residency was associated with an increased odds of coronary artery disease [odds ratio (OR) = 3.05, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.01-9.20] and diabetic nephropathy (OR = 4.90, 95%CI: 1.34-18.04). Individuals with secondary education or higher had an increased risk of coronary artery disease compared with those with only primary education (OR = 2.33, 95%CI: 1.14-4.72). Lack of access to spaces for physical activity was associated with a higher risk of cerebrovascular disease (OR = 4.05, 95%CI: 1.31-12.50). Additionally, receiving diabetes education beyond that provided by the clinic was associated with an increased risk of diabetic nephropathy (OR = 2.15, 95%CI: 1.14-4.05) (Table 4).

| Reference | Variable | Coronary artery disease | P value | Cerebrovascular disease | P value | Peripheral arterial disease | P value | Diabetic retinopathy | P value | Diabetic neuropathy | P value | Diabetic nephropathy | P value |

| Rural | Place of residence (urban) | 3.05 (1.01-9.20) | 0.04 | 0.75 (0.15-3.60) | 0.72 | 4.40 (0.57-34.47) | 0.15 | 1.15 (0.32-7.16) | 0.61 | 1.54 (0.42-5.63) | 0.51 | 4.90 (1.34-18.04) | 0.01 |

| No | Forced displacement (yes) | 0.97 (0.29-3.24) | 0.78 | 3.96 (0.93-16.83) | 0.06 | 0.35 (0.04-2.80) | 0.35 | 1.76 (0.44-6.95) | 0.40 | 0.31 (0.03-2.50) | 0.31 | 0.85 (0.25-2.83) | 0.70 |

| Basic | Educational level (secondary or higher) | 2.33 (1.14-4.72) | 0.01 | 1.09 (0.32-3.72) | 0.81 | 0.56 (0.24-1.32) | 0.18 | 0.61 (0.23-1.62) | 0.33 | 0.73 (0.31-1.70) | 0.47 | 1.25 (0.63-2.50) | 0.51 |

| Single | Marital status (common-law) | 4.01 (0.95-16.87) | 0.05 | 0.84 (0.06-10.45) | 0.89 | 1.36 (0.29-6.36) | 0.69 | 1.36 (0.00-99.00) | 0.98 | 2.12 (0.41-10.85) | 0.36 | 1.05 (0.25-4.40) | 0.94 |

| High | Socioeconomic status (low) | 0.65 (0.19-2.12) | 0.47 | 2.07 (0.22-19.57) | 0.52 | 0.65 (0.14-2.93) | 0.57 | 4.36 (0.48-39.15) | 0.18 | 0.42 (0.08-2.20) | 0.30 | 0.51 (0.15-1.73) | 0.28 |

| Socioeconomic status (medium) | 0.63 (0.21-1.83) | 0.39 | 0.77 (0.08-6.92) | 0.82 | 0.83 (0.21-3.27) | 0.79 | 1.86 (0.21-16.27) | 0.57 | 1.32 (0.32-5.37) | 0.69 | 0.65 (0.21-1.97) | 0.55 | |

| Low | Income (medium) | 0.95 (0.46-1.96) | 0.89 | 0.58 (0.17-1.95) | 0.38 | 0.45 (0.17-1.16) | 0.09 | 0.50 (0.17-1.46) | 0.20 | 1.01 (0.40-2.57) | 0.97 | 1.02 (0.47-2.21) | 0.94 |

| Income (upper-middle) | 1.03 (0.41-2.54) | 0.84 | 0.53 (0.10-2.81) | 0.46 | 0.52 (0.15-1.79) | 0.30 | 1.24 (0.37-4.13) | 0.71 | 1.15 (0.36-3.67) | 0.80 | 2.13 (0.85-5.13) | 0.10 | |

| Income (high) | 1.62 (0.57-4.54) | 0.35 | 0.00 (0.00-99.00) | 0.99 | 0.64 (0.16-2.55) | 0.53 | 0.26 (0.03-2.28) | 0.22 | 0.51 (0.09-2.66) | 0.42 | 0.78 (0.24-2.47) | 0.67 | |

| Yes | Caregiver (no) | 1.44 (0.73-2.81) | 0.28 | 0.60 (0.19-1.88) | 0.38 | 0.51 (0.22-1.17) | 0.11 | 0.61 (0.23-1.60) | 0.32 | 0.68 (0.29-1.56) | 0.36 | 1.10 (0.56-2.16) | 0.77 |

| Yes | Availability for physical activity spaces (no) | 1.20 (0.61-2.34) | 0.58 | 4.05 (1.31-12.50) | 0.01 | 1.58 (0.67-3.69) | 0.28 | 2.28 (0.90-5.81) | 0.08 | 1.58 (0.69-3.16) | 0.27 | 0.66 (0.32-1.37) | 0.27 |

| No | Additional diabetes education (yes) | 1.44 (0.77-2.66) | 0.24 | 0.00 (0.00-99.00) | 0.99 | 1.39 (0.62-3.11) | 0.41 | 1.87 (0.76-4.57) | 0.16 | 2.00 (0.92-4.34) | 0.07 | 2.15 (1.14-4.05) | 0.01 |

In this study of individuals with type 2 diabetes receiving care at a referral military hospital in Bogota, Colombia, specific social determinants of health were associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular complications. Notably, urban residence, higher educational attainment (secondary level or above), limited access to spaces for physical activity, and receipt of diabetes education outside the institutional program were each independently associated with a higher prevalence of coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, and diabetic nephropathy after adjusting for potential confounders such as age, diabetes duration, BMI, and smoking history.

Urban residency emerged as a risk factor for both coronary artery disease and diabetic nephropathy in this cohort. Previous research highlighted that urban environments can influence healthcare access and adherence with recent rural-to-urban migrants potentially facing challenges in treatment adherence[13]. Additionally, exposure to air pollution, particularly fine particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), which is more concentrated in urban areas, has been identified by the World Health Organization as the fourth-leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, contributing to increased cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease risk[14]. Neighborhood characteristics, shaped by factors like urban development and socioeconomic disparities, influence environmental exposures and access to resources, which can impact cardiovascular health through behavioral pathways, like diet and activity, or direct physiological stress mechanisms. While some research suggests potential benefits of urban densification (e.g., lower obesity risk), it might also negatively affect factors like blood pressure.

The association between social determinants and diabetic nephropathy has been studied less. However, a case-control study found a strong association between total dietary diversity and nephropathy, suggesting a benefit with the consumption of fruits and vegetables. Previous studies also highlighted the protective role of dietary patterns rich in plant-based foods on kidney function. A diet rich in plant-based foods provides antioxidants, fiber, and micronutrients to improve blood pressure and lipid profile and reduce oxidative stress and inflammation. However, this study did not address dietary patterns or composition. A possible explanation is the lack of dietary diversity in urban areas of Colombia[15]. In this study 11% of participants were directly or indirectly affected by forced displacement due to armed conflict. Colombia has faced a prolonged armed conflict, primarily affecting rural areas, with peak displacement figures in the 1990s and early 2000s, reaching 730904 displaced individuals in 2003 alone[16]. While this study did not find a significant association between forced displacement and cardiovascular complications, internal migration may contribute to the increased risk of coronary artery disease in urban populations as previous research has shown that rural-to-urban migrants have a higher cardiovascular risk than those who migrate between urban areas[17].

Educational level has been widely recognized as a risk factor for coronary artery disease and cardiovascular events with a well-documented inverse relationship between education and disease risk in many countries[18]. However, this study observed a paradoxical association in which individuals with secondary or higher education had a greater prevalence of coronary artery disease. The initial hypothesis suggested this might reflect the epidemiological transition in urbanizing settings, leading to better access to diagnostics and earlier detection among more educated individuals. This finding contrasts with some Colombian data suggesting higher education is associated with better quality of life in patients.

Potential explanations for this paradox warrant further investigation: (1) Detection bias: Higher educational attainment might correlate with better health literacy, increased health-seeking behavior, or greater access to specialized care within the military health system, leading to higher diagnosis rates rather than higher underlying disease prevalence; (2) Unmeasured confounders: Specific lifestyle factors or occupational exposures prevalent in higher-educated individuals within this specific military-affiliated cohort might play a role; and (3) Complex socioeconomic interactions: While education is a component of socioeconomic status, its interplay with income, occupation, and lifestyle in the context of the specific social and economic landscape of Colombia, particularly within this unique cohort, might differ from patterns seen elsewhere. The “Hispanic paradox” concept, which sometimes shows better health outcomes despite lower socioeconomic status, does not directly explain this finding but highlights the complexity of how socioeconomic and cultural factors interact with health.

Lack of access to physical activity spaces was associated with an increased risk of cerebrovascular disease. Previous studies, such as the ISPEN study conducted in 14 cities across middle-income and high-income countries, found that a greater density of parks was linked to increased levels of physical activity[19]. Additionally, urban environments that promote walkability have been associated with lower blood pressure, reduced BMI, and decreased prevalence of type 2 diabetes and hypertension[20]. Access to green spaces has also been shown to lower the prevalence of hypertension by 1.9%[21]. In a case-control study areas with higher concentrations of green spaces had a 19% lower risk of stroke compared with areas with fewer green spaces[22]. Similarly, a meta-analysis found that access to green spaces was associated with a reduced risk of mortality from cerebrovascular disease[23]. Physical inactivity itself directly impairs vascular function through mechanisms involving reduced shear stress, increased inflammation, and adverse structural changes in blood vessels, contributing significantly to atherosclerosis and cerebrovascular events. Lack of safe, accessible, and appealing spaces acts as a major environmental barrier, hindering the adoption and maintenance of physically active lifestyles[24].

Diabetes education programs aim to enhance treatment adherence and self-care, leading to improved patient satisfaction and quality of life. Structured diabetes education programs have demonstrated benefits in glycemic control[25,26] and have been linked to reductions in all-cause mortality as reported in a meta-analysis[27]. The finding that receiving additional diabetes education outside the clinic program was associated with a higher risk of diabetic nephropathy is counterintuitive, given that structured education generally improves glycemic control and reduces mortality risk. One hypothesis is that unstructured or varied sources of external education might lead to patient confusion, misinformation, or adoption of inadequate self-management strategies, negatively impacting disease control. Alternatively, this could represent reverse causality in which patients experiencing worsening complications (like nephropathy) actively seek out more information from multiple sources. The quality, source, and consistency of external diabetes education requires further assessment in this context[28].

This study had several limitations. A major limitation was its cross-sectional design, which precludes the establishment of causal relationships between the identified social determinants and cardiovascular complications. The associations observed reflect correlations at a single point in time; therefore, longitudinal studies are necessary to confirm causality. Additionally, the study was conducted at a single healthcare center that primarily includes patients from the central region of the country although it serves individuals from various regions of Colombia. Social determinants of health are dynamic and subject to ongoing economic, social, and political changes, which may influence their association with cardiovascular complications over time. Thus, continuous monitoring of population needs is essential. Importantly, this study did not assess indicators related to healthcare access, such as insurance coverage or healthcare utilization, which could be relevant confounders or effect modifiers.

Programs targeting the treatment of people with diabetes mellitus must consider the conditions surrounding the patients and identify the social determinants of health that negatively impact cardiovascular complications, resulting in a lower quality of life and a greater economic burden on health systems. The impact of social determinants on health must be addressed selectively for each population group; therefore, additional studies with population-based samples are needed to establish follow-up, extrapolate the data, and propose causality.

| 1. | Magliano DJ, Boyko EJ; IDF Diabetes Atlas 10th edition scientific committee. IDF Diabetes Atlas [Internet]. 10th ed. Brussels: International Diabetes Federation; 2021. [PubMed] |

| 2. | World Health Organization. Social determinants of health. [cited 7 January 2024]. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1. |

| 3. | Allen J, Balfour R, Bell R, Marmot M. Social determinants of mental health. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2014;26:392-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 508] [Cited by in RCA: 576] [Article Influence: 52.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Daxinger L, Whitelaw E. Understanding transgenerational epigenetic inheritance via the gametes in mammals. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:153-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 424] [Cited by in RCA: 451] [Article Influence: 34.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Stringhini S, Sabia S, Shipley M, Brunner E, Nabi H, Kivimaki M, Singh-Manoux A. Association of socioeconomic position with health behaviors and mortality. JAMA. 2010;303:1159-1166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 776] [Cited by in RCA: 760] [Article Influence: 50.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Shi Y, Vanhoutte PM. Macro- and microvascular endothelial dysfunction in diabetes. J Diabetes. 2017;9:434-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 366] [Article Influence: 45.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | United Nations Development Programme. Human development insights. [cited 7 January 2024]. Available from: https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/country-insights#/ranks. |

| 8. | World Bank Group. Gini index-Colombia. [cited 7 January 2024]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI?locations=CO&most_recent_value_desc=true. |

| 9. | World Economic Forum. Global gender gap report 2023. [cited 7 January 2024]. Available from: https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-gender-gap-report-2023/. |

| 10. | Brinkhues S, Dukers-Muijrers NHTM, Hoebe CJPA, van der Kallen CJH, Koster A, Henry RMA, Stehouwer CDA, Savelkoul PHM, Schaper NC, Schram MT. Social Network Characteristics Are Associated With Type 2 Diabetes Complications: The Maastricht Study. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:1654-1662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cereijo L, Gullón P, Del Cura I, Valadés D, Bilal U, Franco M, Badland H. Exercise facility availability and incidence of type 2 diabetes and complications in Spain: A population-based retrospective cohort 2015-2018. Health Place. 2023;81:103027. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | The R Project. The R Project for Statistical Computing. [cited 7 January 2024]. Available from: https://www.r-project.org. |

| 13. | Zhang X, Lu J, Yang Y, Cui J, Zhang X, Xu W, Song L, Wu C, Wang Q, Wang Y, Wang R, Li X. Cardiovascular disease prevention and mortality across 1 million urban populations in China: data from a nationwide population-based study. Lancet Public Health. 2022;7:e1041-e1050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | World Health Organization. Ambient air pollution: A global assessment of exposure and burden of disease. [cited 25 February 2024]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241511353. |

| 15. | Rezazadegan M, Mirjalili F, Jalilpiran Y, Aziz M, Jayedi A, Setayesh L, Yekaninejad MS, Casazza K, Mirzaei K. The Association Between Dietary Diversity Score and Odds of Diabetic Nephropathy: A Case-Control Study. Front Nutr. 2022;9:767415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Comisión para el Esclarecimiento de la Verdad, la Convivencia y la No Repetición. Resistir no es aguantar: violencias y daños contra los pueblos étnicos de Colombia. Tomo 9. Primera edición. Bogotá: Comisión de la Verdad, 2022: 501. |

| 17. | Jansen ES, Agyemang C, Boateng D, Danquah I, Beune E, Smeeth L, Klipstein-Grobusch K, Stronks K, Meeks KAC. Rural and urban migration to Europe in relation to cardiovascular disease risk: does it matter where you migrate from? Public Health. 2021;196:172-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Rosengren A, Smyth A, Rangarajan S, Ramasundarahettige C, Bangdiwala SI, AlHabib KF, Avezum A, Bengtsson Boström K, Chifamba J, Gulec S, Gupta R, Igumbor EU, Iqbal R, Ismail N, Joseph P, Kaur M, Khatib R, Kruger IM, Lamelas P, Lanas F, Lear SA, Li W, Wang C, Quiang D, Wang Y, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Mohammadifard N, Mohan V, Mony PK, Poirier P, Srilatha S, Szuba A, Teo K, Wielgosz A, Yeates KE, Yusoff K, Yusuf R, Yusufali AH, Attaei MW, McKee M, Yusuf S. Socioeconomic status and risk of cardiovascular disease in 20 low-income, middle-income, and high-income countries: the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiologic (PURE) study. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7:e748-e760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 367] [Article Influence: 61.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sallis JF, Cerin E, Conway TL, Adams MA, Frank LD, Pratt M, Salvo D, Schipperijn J, Smith G, Cain KL, Davey R, Kerr J, Lai PC, Mitáš J, Reis R, Sarmiento OL, Schofield G, Troelsen J, Van Dyck D, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Owen N. Physical activity in relation to urban environments in 14 cities worldwide: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2016;387:2207-2217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 741] [Cited by in RCA: 615] [Article Influence: 68.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Nieuwenhuijsen MJ. Influence of urban and transport planning and the city environment on cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2018;15:432-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Schutte AE, Srinivasapura Venkateshmurthy N, Mohan S, Prabhakaran D. Hypertension in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Circ Res. 2021;128:808-826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 44.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Cheruvalath H, Homa J, Singh M, Vilar P, Kassam A, Rovin RA. Associations Between Residential Greenspace, Socioeconomic Status, and Stroke: A Matched Case-Control Study. J Patient Cent Res Rev. 2022;9:89-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bianconi A, Longo G, Coa AA, Fiore M, Gori D. Impacts of Urban Green on Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Diseases-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20:5966. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lee JL, Kim Y, Huh S, Shin YI, Ko SH. Status and Barriers of Physical Activity and Exercise in Community-Dwelling Stroke Patients in South Korea: A Survey-Based Study. Healthcare (Basel). 2024;12:697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kurita M, Satoh H, Kaga H, Kadowaki S, Someya Y, Tosaka Y, Nishida Y, Ikeda F, Tamura Y, Watada H. A 7 day inpatient diabetes education program improves quality of life and glycemic control 12 months after discharge. J Diabetes Investig. 2023;14:811-820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lyu QY, Huang JW, Li YX, Chen QL, Yu XX, Wang JL, Yang QH. Effects of a nurse led web-based transitional care program on the glycemic control and quality of life post hospital discharge in patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021;119:103929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | He X, Li J, Wang B, Yao Q, Li L, Song R, Shi X, Zhang JA. Diabetes self-management education reduces risk of all-cause mortality in type 2 diabetes patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocrine. 2017;55:712-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chen P, Callisaya M, Wills K, Greenaway T, Winzenberg T. Cognition, educational attainment and diabetes distress predict poor health literacy in diabetes: A cross-sectional analysis of the SHELLED study. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0267265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |