Published online Apr 15, 2025. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v16.i4.99151

Revised: December 10, 2024

Accepted: January 18, 2025

Published online: April 15, 2025

Processing time: 169 Days and 2.8 Hours

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is a prevalent type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) complication. Further, the risk stratification before angiography may help diag

To compare the differences in coronary imaging between patients with T2DM with and without CHD, determine the risk factors of T2DM complicated with CHD, and establish a predictive tool for diagnosing CHD in T2DM.

This study retrospectively analyzed 103 patients with T2DM from January 2022 to May 2024. They are categorized based on CHD occurrence into: (1) The control group, consisting of patients with T2DM without CHD; and (2) The observation group, which includes patients with T2MD with CHD. Age, sex, smoking and drinking history, CHD family history, metformin (MET) treatment pre-admission, body mass index, fasting blood glucose (FBG), triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), serum creatinine, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), and coronary imaging data of both groups were collected from the medical record system. Logistic risk analysis was conducted to screen risk factors. The prediction model’s prediction efficiency was evaluated with receiver operating characteristic curves.

The control and observation groups consisted of 48 and 55 cases, respectively. The two groups were statistically different in terms of age (t = 2.006, P = 0.048), FBG (t = 6.038, P = 0.000), TG (t = 2.015, P = 0.047), LDL-C (t = 2.017, P = 0.046), and BUN (t = 2.035, P = 0.044). The observation group demonstrated lower proportions of patients receiving MET (χ2 = 5.073, P = 0.024) and higher proportions of patients with HbA1c of > 7.0% (χ2 = 6.980, P = 0.008) than the control group. The observation group consisted of 15, 17, and 23 cases of moderate stenosis, severe stenosis, and occlusion, respectively, with a greater number of coronary artery occlusion cases than the control group (χ2 = 6.399, P = 0.041). The observation group consisted significantly higher number of diffuse lesion cases at 35 compared with the control group (χ2 = 15.420, P = 0.000). The observation group demonstrated a higher right coronary artery (RCA) stenosis index (t = 6.730, P = 0.000), circumflex coronary artery (LCX) stenosis index (t = 5.738, P = 0.000), and total stenosis index (t = 7.049, P = 0.000) than the control group. FBG [odds ratio (OR) = 1.472; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.234-1.755; P = 0.000] and HbA1c (OR = 3.197; 95%CI: 1.149-8.896; P = 0.026) were independent risk factors for T2DM complicated with CHD, whereas MET (OR = 0.350; 95%CI: 0.129-0.952; P = 0.040) was considered a protective factor for CHD in T2DM.

Coronary artery occlusion is a prevalent complication in patients with T2DM. Patients with T2MD with CHD demonstrated a higher degree of RCA and LCX stenosis than those with T2DM without CHD. FBG, HbA1c, and MET treatment history are risk factors for T2DM complicated with CHD.

Core Tip: The present study reveals the imaging characteristics of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) combined with coronary heart disease (CHD). The risk analysis model revealed fasting blood glucose and glycosylated hemoglobin as independent risk factors for T2DM complicated by CHD, and metformin treatment as an independent protective factor. A prediction model for clinical assessment of T2DM complicated with CHD is established, which will promote the development of early diagnosis and risk stratification of T2DM complicated with CHD.

- Citation: Pan CJ, Wang T, Yin RH, Tang XQ, Hu CH. Coronary imaging characteristics and risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus with coronary heart disease complication. World J Diabetes 2025; 16(4): 99151

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v16/i4/99151.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v16.i4.99151

Diabetes mellitus (DM), one of the most prevalent non-communicable diseases, exhibits increasing incidence and prevalence annually. Statistics reported that 537 million patients suffered from DM in 2021, and this is expected to increase to 643 million by 2030[1]. Type 2 DM (T2DM) is the most prevalent DM type, accounting for approximately 90% of patients diagnosed with DM. Pancreatic B-cell dysfunction and insulin resistance in the liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue are the leading causes of T2DM. T2DM increases the risk of cardiovascular adverse events in addition to blood glucose and lipid abnormalities. The risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with T2DM is estimated to be twice as high as that in patients without T2DM[2]. Coronary heart disease (CHD) is a cardiovascular disease characterized by insufficient myocardial blood and oxygen supply[3], which is the leading cause of global morbidity and mortality. Research reveals that T2DM is a crucial risk factor for CHD[4]. Statistics reported up to an 11% incidence rate of CHD in T2DM[5], which is the primary cause of death in patients with T2DM. Clinical research has demonstrated a 10-year mortality rate of approximately 34.5%-36.4% in patients with T2DM complicated with CHD[6]. CHD has posed a huge health burden on patients with T2DM. Effective and accurate risk assessment for CHD in patients with T2DM is currently an urgent issue that warrants solution.

Patients with CHD are accompanied by coronary artery stenosis or occlusion. Coronary imaging helps determine CHD in patients with T2DM. Radionuclide myocardial perfusion imaging, single-photon emission computed tomography (CT), positron emission tomography, and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging are CHD imaging tests. An increasing number of studies utilize imaging tools to collect information on myocardial ischemia and coronary artery calcification in patients for systematical assessment of the presence and severity of CHD. Min et al[7] performed coronary angiography on patients with DM and revealed that 70% of patients had coronary atherosclerosis, whereas 27.8% developed obstructive coronary atherosclerosis. However, the application of angiography in T2DM remains limited. Approximately 25%-35% of patients with DM combined with asymptomatic CHD present no obvious plaques on coronary angiography, and a relatively large proportion of patients experienced no or only slight coronary atherosclerosis[8]. The lack of comprehensive understanding of coronary imaging in patients with T2DM combined with CHD may cause the above limitations. Additionally, the risk stratification before angiography may contribute to the early diagnosis of T2DM combined with CHD. Improving the clinical diagnosis rate of T2DM combined with CHD is helpful by clarifying the coronary imaging characteristics of patients with T2DM combined with CHD and mining the risk factors of the disease.

At present, few studies have investigated the coronary imaging characteristics and risk factors of patients with T2DM combined with CHD. Hence, this study aims to conduct a retrospective analysis of the patients with T2DM admitted to our hospital, compare the differences in coronary artery imaging between patients with and without CHD, and analyze the risk factors. This aims to improve people’s scientific understanding of the vascular characteristics of T2DM combined with CHD and to provide a powerful assessment tool for judging the risk of CHD in patients with T2DM.

This retrospective analysis included 103 patients with T2DM from January 2022 to May 2024 at The Affiliated Changzhou No. 2 People’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University. They were grouped according to the presence of CHD, with the control and observation groups consisting of patients with T2DM combined without CHD and those with T2DM combined with CHD, respectively. Inclusion criteria were: (1) Patients who underwent coronary angiography with coronary imaging data available; (2) Those who were diagnosed with CHD under the European Society of Cardiology 2019 Diagnostic Criteria; and (3) Patients diagnosed with T2DM following the Guideline for T2DM prevention and treatment in China (2024 edition).

Exclusion criteria were: (1) Patients with previous intravenous thrombolysis, percutaneous coronary intervention, or coronary artery bypass grafting; (2) Those with severe valvulopathy, severe arrhythmia, severe heart failure, myocarditis, cardiomyopathy, or pericarditis; (3) Patients with acute/chronic infection or severe hepatic and renal insufficiency; (4) Those with hematological diseases, immune system diseases or malignant tumors; and (5) Those with missing or incomplete medical records.

The following data of both groups were collected from the medical record system: Age, sex, smoking and drinking history, CHD family history, metformin (MET) treatment before admission, body mass index (BMI), fasting blood glucose (FBG), triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (TC), high/Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C/LDL-C), serum creatinine (SCr), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), and coronary imaging.

Patients fasted for > 8 hours post-admission, and the venous blood samples were then collected at 7:00 the next day. FBG, TG, TC, HDL-C/LDL-C, SCr, BUN, ALT, AST, and HbA1c were measured with a BS-100M fully automatic biochemical analyzer (BS-100M, Mindray, Shenzhen, China).

The patient underwent an imaging examination post-admission. Coronary angiography was performed by a Siemens large C-arm angiography machine (model: Artis zee floor; Siemens, Germany). Iodixanol injection (produced by Yangtze River Pharmaceutical, Taizhou, Jiangsu province, China; batch number: 19072561) was the contrast agent used. CT scanning for the coronary artery was performed by a Siemens 128-layer CT machine (model: SOMATOM Definition Edge; Siemens, Germany). We have added the abovementioned methods in “2.3 biochemical detection” and “2.4 imaging examination,” respectively.

The degree of stenosis was assessed as mild (< 50%), moderate (50%-75%), severe (75%-99%), or occlusion (100%). Coronary artery stenosis assessments were specific to the proximal, middle, and distal segments of the right coronary artery (RCA), left main trunk (LMT), proximal, middle, and distal segments of the left anterior descending artery (LAD), diagonal branch, proximal and distal circumflex coronary artery (LCX), and obtuse marginal branch. The stenosis index of RCA, LCX, LAD, and LMT as well as the total coronary stenosis index were statistically counted.

Independent samples t-tests were conducted for inter-group comparisons of measurement data, and χ2 tests were utilized for between-group comparisons of counting data. Risk factors were screened with Logistic regression analysis, and the model’s prediction efficiency was evaluated with receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. P values of < 0.05 indicated that the comparison was statistically significant. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 23.0 software was utilized for statistical analysis.

This study enrolled 103 patients. The control group consisted of 48 cases, including 29 males and 19 females, aged 61.23 ± 10.22 years. The observation group included 55 patients with a male-to-female ratio of 31:24 and an age of 65.20 ± 9.96 years. By comparison, we revealed no significant inter-group differences in sex, smoking and drinking history, CHD family history, BMI, TC, HDL-C, SCr, ALT, and AST (P > 0.05), but significant differences were determined in age (observation vs control: 65.20 ± 9.96 vs 61.21 ± 10.21, t = 2.006, P = 0.048), FBG (observation vs control: 14.72 ± 3.92 vs 10.58 ± 2.87, t = 6.038, P = 0.000), TG (observation vs control: 2.41 ± 0.82 vs 2.09 ± 0.79, t = 2.015, P = 0.047), LDL-C (observation vs control: 3.22 ± 0.63 vs 2.98 ± 0.57, t = 2.017, P = 0.046), and BUN (observation vs control: 6.05 ± 1.58 vs 5.49 ± 1.14, t = 2.035, P = 0.044). Table 1 presents the results.

| Characteristic | Control group (n = 48) | Observation group (n = 55) | χ2/t value | P value |

| Age (years) | 61.21 ± 10.21 | 65.20 ± 9.96 | 2.006 | 0.048 |

| Sex | 0.173 | 0.677 | ||

| Male | 29 (60.42) | 31 (56.36) | ||

| Female | 19 (39.58) | 24 (43.64) | ||

| History of smoking and drinking | 0.109 | 0.741 | ||

| With | 26 (54.17) | 28 (50.91) | ||

| Without | 22 (45.83) | 27 (49.09) | ||

| Family history of coronary heart disease | 2.746 | 0.098 | ||

| With | 15 (31.25) | 26 (47.27) | ||

| Without | 33 (68.75) | 29 (52.73) | ||

| BMI (mmol/L) | 23.15 ± 2.69 | 24.09 ± 2.74 | 1.752 | 0.083 |

| FBG (mmol/L) | 10.58 ± 2.87 | 14.72 ± 3.92 | 6.038 | 0.000 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 2.09 ± 0.79 | 2.41 ± 0.82 | 2.015 | 0.047 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 5.82 ± 1.08 | 6.18 ± 1.12 | 1.655 | 0.101 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.13 ± 0.52 | 1.24 ± 0.48 | 1.116 | 0.267 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.98 ± 0.57 | 3.22 ± 0.63 | 2.017 | 0.046 |

| SCr (μmol/L) | 62.77 ± 10.87 | 63.76 ± 11.25 | 0.453 | 0.652 |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 5.49 ± 1.14 | 6.05 ± 1.58 | 2.035 | 0.044 |

| ALT (U/L) | 25.88 ± 5.92 | 27.71 ± 6.31 | 1.511 | 0.134 |

| AST (U/L) | 24.72 ± 6.74 | 25.41 ± 6.17 | 0.542 | 0.589 |

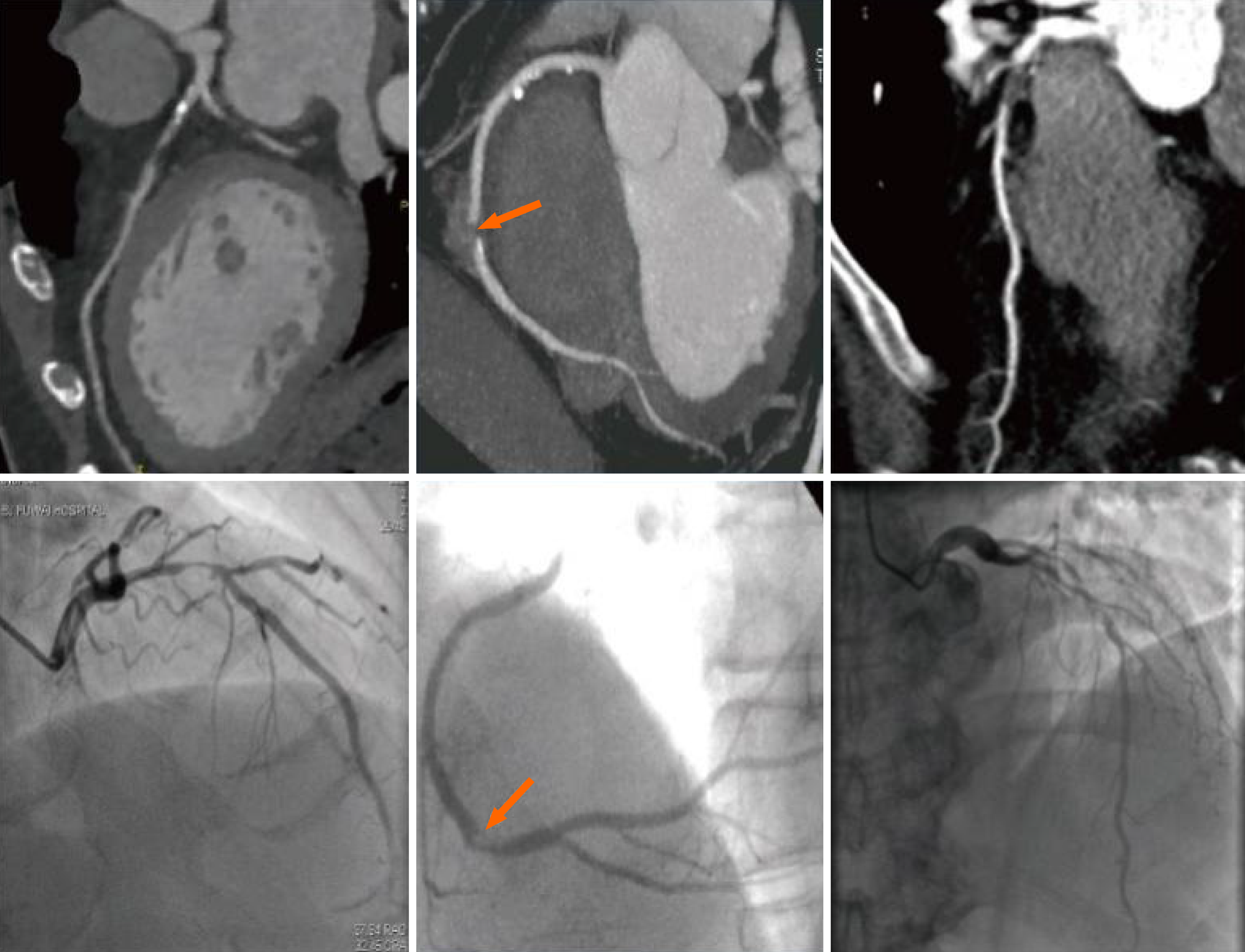

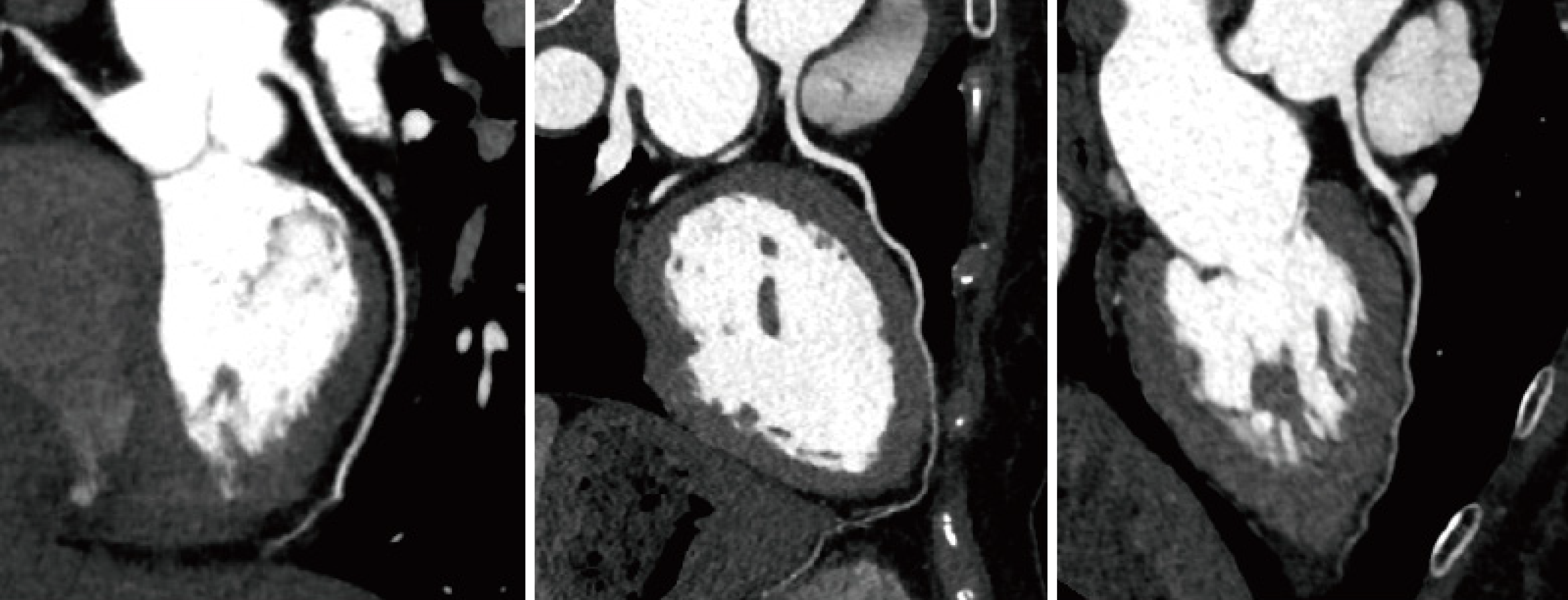

Figure 1 illustrates the coronary imaging data from three patients with T2DM complicated with CHD during their hospital stay. Coronary artery imaging revealed significant local luminal stenosis or occlusion with branched plaque infiltrates (both calcified and non-calcified). Additionally, Figure 2 demonstrated the coronary images of patients with T2DM without CHD whose coronary arteries did not develop significant local luminal stenosis or occlusion with branched plaque infiltrates. Table 2 showed a greater number of patients with diffuse lesions (observation vs control: 63.64% vs 25.00%, χ2 = 15.420, P = 0.000) and more cases of coronary artery occlusion in the observation group than in the control group (observation vs control: 41.82% vs 22.92%, χ2 = 6.399, P = 0.041). Table 3 showed the stenosis indices of both groups. Statistical comparison indicated that the RCA stenosis index (observation vs control: 3.98 ± 1.05 vs 2.57 ± 1.07, t = 6.730, P = 0.000), LCX stenosis index (observation vs control: 3.37 ± 1.14 vs 2.09 ± 1.12, t = 5.738, P = 0.000), and total stenosis index (observation vs control: 11.91 ± 1.94 vs 9.09 ± 2.12, t = 7.049, P = 0.000) were significantly higher in the observation group than in the control group. Also, we compared the coronary imaging characteristics and the stenosis index in males and females. As shown in Table 4, there were no statistical changes in diffuse lesion (male vs female: χ2 = 1.837, P = 0.175) and degree of stenosis (male vs female: χ2 = 2.898, P = 0.235) in males and females. Also, RCA (t = 0.432, P = 0.666), LCX (t = 1.238, P = 0.219), LAD (t = 0.417, P = 0.677), LMT (t = 0.134, P = 0.894) and total index (t = 0.222, P = 0.825) between males and females were not different in statistics (Table 5). Thus, gender might be not associated with coronary imaging in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus with coronary heart disease complication.

| Characteristic | Control group (n = 48) | Observation group (n = 55) | χ2 value | P value |

| Diffuse lesion | 15.420 | 0.000 | ||

| With | 12 (25.00) | 35 (63.64) | ||

| Without | 36 (75.00) | 20 (36.36) | ||

| Degree of stenosis | 6.399 | 0.041 | ||

| Moderate | 24 (50.00) | 15 (27.27) | ||

| Severe | 13 (27.08) | 17 (30.91) | ||

| Occlusion | 11 (22.92) | 23 (41.82) |

| Characteristic | Control group (n = 48) | Observation group (n = 55) | t value | P value |

| RCA stenosis index | 2.57 ± 1.07 | 3.98 ± 1.05 | 6.730 | 0.000 |

| LCX stenosis index | 2.09 ± 1.12 | 3.37 ± 1.14 | 5.738 | 0.000 |

| LAD stenosis index | 3.38 ± 1.32 | 3.59 ± 1.08 | 0.890 | 0.376 |

| LMT stenosis index | 1.05 ± 0.41 | 0.97 ± 0.33 | 1.096 | 0.275 |

| Total stenosis index | 9.09 ± 2.12 | 11.91 ± 1.94 | 7.049 | 0.000 |

| Characteristic | Male (n = 60) | Female (n = 43) | χ2 value | P value |

| Diffuse lesion | 1.837 | 0.175 | ||

| With | 24 (40.00) | 23 (53.49) | ||

| Without | 36 (60.00) | 20 (46.51) | ||

| Degree of stenosis | 2.898 | 0.235 | ||

| Moderate | 23 (38.33) | 16 (37.21) | ||

| Severe | 14 (23.33) | 16 (37.21) | ||

| Occlusion | 23 (38.33) | 11 (25.58) |

| Characteristic | Male (n = 60) | Female (n = 43) | t value | P value |

| RCA stenosis index | 3.28 ± 1.31 | 3.39 ± 1.22 | 0.432 | 0.666 |

| LCX stenosis index | 2.91 ± 1.31 | 2.59 ± 1.27 | 1.238 | 0.219 |

| LAD stenosis index | 3.45 ± 1.13 | 3.55 ± 1.29 | 0.417 | 0.677 |

| LMT stenosis index | 1.01 ± 0.36 | 1.00 ± 0.39 | 0.134 | 0.894 |

| Total stenosis index | 10.64 ± 2.48 | 10.53 ± 2.47 | 0.222 | 0.825 |

Table 6 shows the differences in hypoglycemic therapy and HbA1c levels between the two groups. The χ2 test analysis revealed that the observation group demonstrated lower proportions of patients receiving MET (observation vs control: 38.18% vs 60.42%, χ2 = 5.073, P = 0.024) and higher proportions of patients with HbA1c of > 7.0% (observation vs control: 52.73% vs 27.08%, χ2 = 6.980, P = 0.008) than the control group.

| Characteristic | Control group (n = 48) | Observation group (n = 55) | χ2 value | P value |

| Metformin treatment | 5.073 | 0.024 | ||

| With | 29 (60.42) | 21 (38.18) | ||

| Without | 19 (39.58) | 34 (61.82) | ||

| HbA1c | 6.980 | 0.008 | ||

| > 7.0% | 13 (27.08) | 29 (52.73) | ||

| ≤ 7.0% | 35 (72.92) | 26 (47.27) |

Univariate logistic analysis determined FBG [odds ratio (OR) = 1.444; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.231-1.694; P = 0.000], BUN (OR = 1.342; 95%CI: 1.003-1.794; P = 0.048), and HbA1c (OR = 3.003; 95%CI: 1.312-6.872; P = 0.009) as risk factors for T2DM complicated with CHD and MET treatment (OR = 0.405; 95%CI: 0.183-0.895; P = 0.026) as a protective factor (Table 7).

| Characteristic | B | SE | Wals | df | OR | 95%CI | P value |

| Age | 0.040 | 0.021 | 3.807 | 1 | 1.041 | 1.000-1.084 | 0.051 |

| FBG | 0.368 | 0.081 | 20.418 | 1 | 1.444 | 1.231-1.694 | 0.000 |

| TG | 0.506 | 0.259 | 3.826 | 1 | 1.658 | 0.999-2.752 | 0.050 |

| LDL-C | 0.673 | 0.343 | 3.853 | 1 | 1.959 | 1.001-3.835 | 0.050 |

| BUN | 0.294 | 0.148 | 3.926 | 1 | 1.342 | 1.003-1.794 | 0.048 |

| Metformin (with vs without) | -0.905 | 0.405 | 4.989 | 1 | 0.405 | 0.183-0.895 | 0.026 |

| HbA1c (> 7.0% vs ≤ 7.0%) | 1.100 | 0.422 | 6.776 | 1 | 3.003 | 1.312-6.872 | 0.009 |

Multivariate logistic analysis demonstrated FBG (OR = 1.472; 95%CI: 1.234-1.755; P = 0.000) and HbA1c (OR = 3.197; 95%CI: 1.149-8.896; P = 0.026) as independent risk factors for T2DM complicated with CHD and MET treatment (OR = 0.350; 95%CI: 0.129-0.952; P = 0.040) as an independent protective factor (Table 8).

| Characteristic | B | SE | Wals | df | OR | 95%CI | P value |

| FBG | 0.386 | 0.090 | 18.533 | 1 | 1.472 | 1.234-1.755 | 0.000 |

| BUN | 0.311 | 0.185 | 2.824 | 1 | 1.365 | 0.950-1.963 | 0.093 |

| Metformin (with vs without) | -1.050 | 0.510 | 4.231 | 1 | 0.350 | 0.129-0.952 | 0.040 |

| HbA1c (> 7.0% vs ≤ 7.0%) | 1.162 | 0.522 | 4.953 | 1 | 3.197 | 1.149-8.896 | 0.026 |

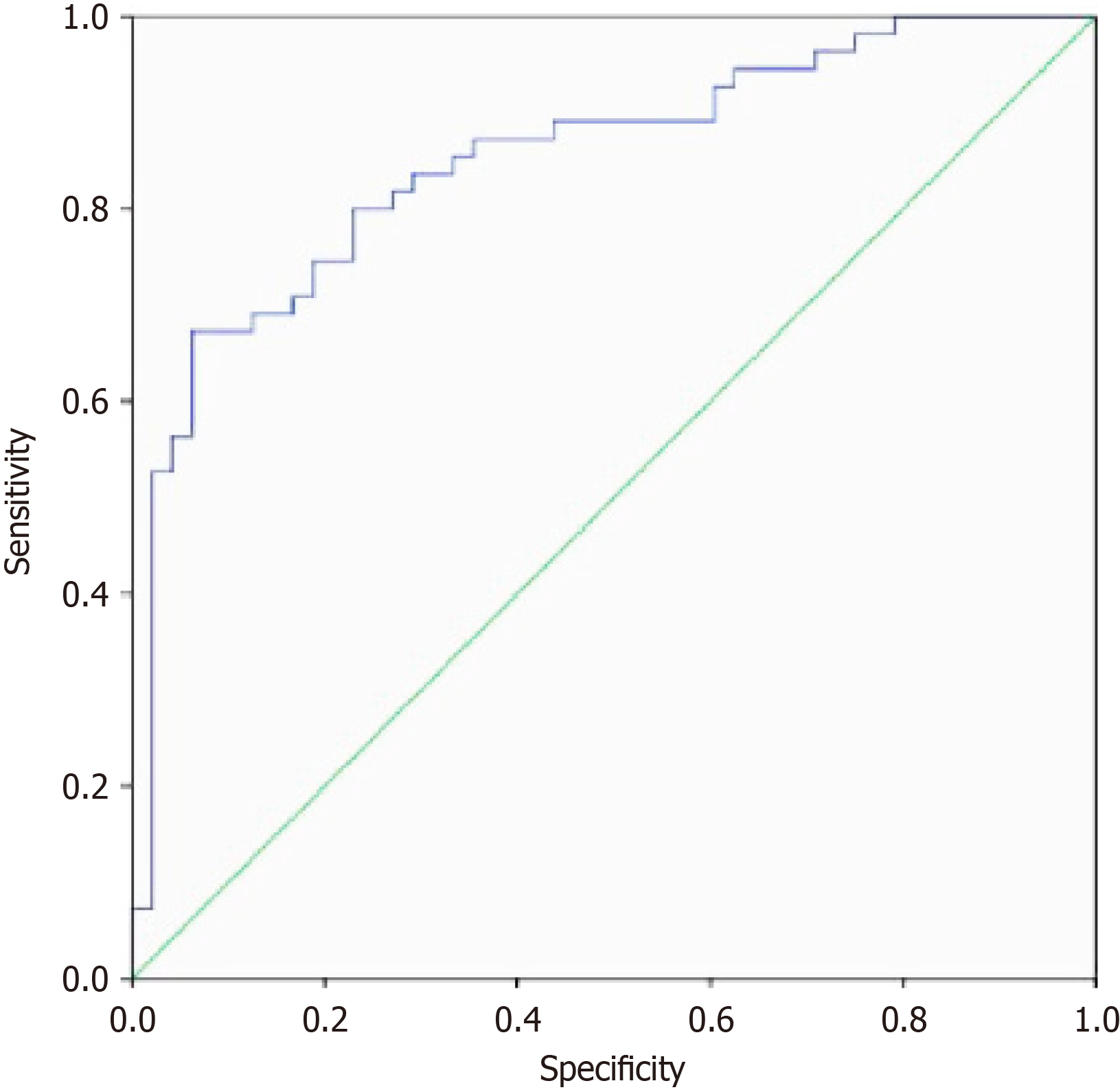

Finally, a prediction model for determining T2DM complicated with CHD was constructed based on the above risk factors, with the model’s prediction efficiency tested with ROC curves. The area under the curve value was 0.835 (95%CI: 0.721-0.949, P = 0.000), indicating good diagnostic performance of the model (Figure 3).

CHD is a prevalent complication in patients with T2DM and may increase the risk of death[9,10]. The pathogenesis of T2DM complicated with CHD remains unclear, and its coronary imaging characteristics warrant further investigation. In this study, the coronary imaging characteristics and risk factors of CHD in T2DM were examined, indicating that: (1) Coronary artery occlusion was dominant in patients with T2DM complicated with CHD, and the degree of RCA and LCX stenosis was higher than that in patients with T2DM without CHD; and (2) FBG, HbA1c, and MET treatment history were risk factors for T2DM complicated with CHD.

The special physiological environment of DM increases arterial plaque formation, thereby promoting the risk of CHD[11-13]. Patients with DM demonstrate a significantly higher incidence of lumen stenosis and are more susceptible to diffuse vascular disease than those with no DM[14]. Further, Mrgan et al[15] reported a higher likelihood of developing coronary plaques in patients with T2DM. Furthermore, we presented the arterial imaging information of patients with DM with CHD. Obvious local lumen stenosis or occlusion was observed in both coronary angiography and coronary CT angiography, accompanied by branch plaque infiltration. Therefore, coronary artery imaging tests need to be conducted for patients with DM suspected of CHD. Meanwhile, we demonstrated certain differences in the coronary artery images of patients with DM with or without CHD. This study compared the coronary angiography evidence of patients with T2DM with or without CHD and revealed that patients with T2DM with CHD were mainly characterized by coronary artery occlusion, with higher degrees of RCA and LCX stenosis compared to those without CHD. Further, T2DM cases with CHD have more severe arterial stenosis than those with DM without CHD. Therefore, special attention should be paid to patients with T2DM who demonstrate coronary artery stenosis to assess CHD possibilities.

Subsequently, this study analyzed the clinical data of patients to investigate the independent factors of T2DM combined with CHD. Multivariate logistic analysis determined FBG and HbA1c as independent risk factors for T2DM with CHD and MET treatment as an independent protective factor. CHD occurrence and development are closely associated with fluctuations in blood glucose levels[16]. Evidence indicates a significant correlation between FBG and the susceptibility to severe coronary artery disease exhibited by triple vascular disease or myocardial infarction. Patients with CHD with impaired FBG levels demonstrated a higher risk of developing triple vascular disease than those with single- and double-vessel coronary disease[17]. Further, FBG can be utilized to predict the risk of stent restenosis after percutaneous coronary intervention[18]. Hence, FBG demonstrated potential in predicting CHD. HbA1c is a crucial indicator for measuring T2DM and plays a vital role in CHD occurrence and development. Cheng et al[19] confirmed a significant positive correlation between HbA1c levels and the incidence of carotid artery plaques, intima-media thickness, and plaque echogenicity, indicating that HbA1c levels are crucial for plaque formation. Wang et al[20] revealed significantly higher HbA1c levels in patients with multi-vessel CHD than in those without CHD, indicating that HbA1c may be closely related to CHD progression. HbA1c at baseline and during the follow-up period was positively correlated with the CHD risk during the 6-year follow-up of patients with DM[21]. The study concluded the same about HbA1c.

MET is a first-line treatment for cardiac protection in patients with T2DM; thus, MET treatment history may affect the risk of CHD in T2DM. Jong et al[22] revealed that MET helped reduce the risk of death in patients with T2DM complicated with CHD. A retrospective analysis of 313 patients with T2DM complicated with CHD revealed optical coherence tomography evidence of the effect of MET on plaque microstructure, of which results indicated that patients receiving MET demonstrated smaller lipid arcs, shorter longitudinal lengths, lower cholesterol crystallization frequencies, and punctate calcifications, whereas insulin treatment did not exhibit these effects[23]. This indicates that MET may exert a plaque-stabilizing effect on patients with T2DM, thereby inhibiting atherosclerosis progression and reducing the risk of CHD. These influencing factors are expected to be utilized in the clinical assessment of patients with T2DM to distinguish those with CHD from those without CHD. Hence, this study established a prediction model following the above factors, and the ROC curve analysis revealed the good diagnostic efficiency of the model in determining T2DM complicated with CHD. Therefore, FBG, HbA1c, LDL-C, and MET treatment history play a crucial role in the risk stratification of T2DM.

This study has the following limitations. First, selection bias may occur due to the retrospective study design. Second, this study is single-centered, so the unique practice of a single research institution may influence the results. Third, the typical cases that can be recruited in this study are limited because the patients come from the same unit, thereby affecting the statistical power of the research data. Fourth, this study constructed a prediction model for the risk assessment of CHD occurrence but failed to conduct internal validation due to the limited sample size. A multi-center prospective study is warranted to expand the scope of case recruitment, increase the actual sample size of the study, and investigate the reliability of the prediction model by setting up training and validation sets to address the above issues.

All in all, this study demonstrates the imaging characteristics of patients with T2DM complicated with CHD. The risk analysis model demonstrated FBG and HbA1c are independent risk factors for T2DM complicated with CHD and MET treatment as an independent protective factor. A prediction model for clinical assessment of T2DM complicated with CHD is constructed, which will promote the development of early diagnosis and risk stratification of T2DM complicated with CHD.

| 1. | Magliano DJ, Boyko EJ, IDF Diabetes Atlas 10th edition scientific committee. IDF DIABETES ATLAS [Internet]. Brussels: International Diabetes Federation; 2021. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Yun JS, Ko SH. Current trends in epidemiology of cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular risk management in type 2 diabetes. Metabolism. 2021;123:154838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 35.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Shahjehan RD, Sharma S, Bhutta BS. Coronary Artery Disease. 2024 Oct 9. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Goodarzi MO, Rotter JI. Genetics Insights in the Relationship Between Type 2 Diabetes and Coronary Heart Disease. Circ Res. 2020;126:1526-1548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Ma CX, Ma XN, Guan CH, Li YD, Mauricio D, Fu SB. Cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus: progress toward personalized management. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022;21:74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 70.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wang R, Serruys PW, Gao C, Hara H, Takahashi K, Ono M, Kawashima H, O'leary N, Holmes DR, Witkowski A, Curzen N, Burzotta F, James S, van Geuns RJ, Kappetein AP, Morel MA, Head SJ, Thuijs DJFM, Davierwala PM, O'Brien T, Fuster V, Garg S, Onuma Y. Ten-year all-cause death after percutaneous or surgical revascularization in diabetic patients with complex coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2021;43:56-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Min JK, Labounty TM, Gomez MJ, Achenbach S, Al-Mallah M, Budoff MJ, Cademartiri F, Callister TQ, Chang HJ, Cheng V, Chinnaiyan KM, Chow B, Cury R, Delago A, Dunning A, Feuchtner G, Hadamitzky M, Hausleiter J, Kaufmann P, Kim YJ, Leipsic J, Lin FY, Maffei E, Raff G, Shaw LJ, Villines TC, Berman DS. Incremental prognostic value of coronary computed tomographic angiography over coronary artery calcium score for risk prediction of major adverse cardiac events in asymptomatic diabetic individuals. Atherosclerosis. 2014;232:298-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Saraste A, Knuuti J, Bax J. Screening for Coronary Artery Disease in Patients with Diabetes. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2023;25:1865-1871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Duggan JP, Peters AS, Trachiotis GD, Antevil JL. Epidemiology of Coronary Artery Disease. Surg Clin North Am. 2022;102:499-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 33.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wong ND, Sattar N. Cardiovascular risk in diabetes mellitus: epidemiology, assessment and prevention. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2023;20:685-695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 83.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Karagiannidis E, Moysidis DV, Papazoglou AS, Panteris E, Deda O, Stalikas N, Sofidis G, Kartas A, Bekiaridou A, Giannakoulas G, Gika H, Theodoridis G, Sianos G. Prognostic significance of metabolomic biomarkers in patients with diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022;21:70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Clodi M, Saely CH, Hoppichler F, Resl M, Steinwender C, Stingl H, Wascher TC, Winhofer Y, Sourij H. [Diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease and heart disease (Update 2023)]. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2023;135:201-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Xiao H, Ma Y, Zhou Z, Li X, Ding K, Wu Y, Wu T, Chen D. Disease patterns of coronary heart disease and type 2 diabetes harbored distinct and shared genetic architecture. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022;21:276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zhou HT, Zhao DL, Wang GK, Wang TZ, Liang HW, Zhang JL. Assessment of high sensitivity C-reactive protein and coronary plaque characteristics by computed tomography in patients with and without diabetes mellitus. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2020;20:435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mrgan M, Nørgaard BL, Dey D, Gram J, Olsen MH, Gram J, Sand NPR. Coronary flow impairment in asymptomatic patients with early stage type-2 diabetes: Detection by FFR(CT). Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2020;17:1479164120958422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chen J, Yin D, Dou K. Intensified glycemic control by HbA1c for patients with coronary heart disease and Type 2 diabetes: a review of findings and conclusions. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22:146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chen C, Chen Y, Xiao J, Zhang Y, Yang Z, Yang P, Lu N, Yi K, Chen X, Chen S, O'Gara MSc MC, O'Meara M, Ye S, Tan X. Association of Impaired Fasting Blood Glucose With Triple Coronary Artery Stenosis and Myocardial Infarction Among Patients With Coronary Artery Stenosis. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10:820124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chen GC, Huang X, Ruan ZB, Zhu L, Wang MX, Lu Y, Tang CC. Fasting blood glucose predicts high risk of in-stent restenosis in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention: a cohort study. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2023;57:2286885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cheng X, Li Z, Yang M, Liu Y, Wang S, Huang M, Gao S, Yang R, Li L, Yu C. Association of HbA1c with carotid artery plaques in patients with coronary heart disease: a retrospective clinical study. Acta Cardiol. 2023;78:442-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wang J, Huang X, Fu C, Sheng Q, Liu P. Association between triglyceride glucose index, coronary artery calcification and multivessel coronary disease in Chinese patients with acute coronary syndrome. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022;21:187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zhao W, Katzmarzyk PT, Horswell R, Wang Y, Johnson J, Hu G. HbA1c and coronary heart disease risk among diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:428-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jong CB, Chen KY, Hsieh MY, Su FY, Wu CC, Voon WC, Hsieh IC, Shyu KG, Chong JT, Lin WS, Hsu CN, Ueng KC, Lai CL. Metformin was associated with lower all-cause mortality in type 2 diabetes with acute coronary syndrome: A Nationwide registry with propensity score-matched analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2019;291:152-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kataoka Y, Nicholls SJ, Andrews J, Uno K, Kapadia SR, Tuzcu EM, Nissen SE, Puri R. Plaque microstructures during metformin therapy in type 2 diabetic subjects with coronary artery disease: optical coherence tomography analysis. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2022;12:77-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |