Published online Apr 15, 2025. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v16.i4.97201

Revised: October 28, 2024

Accepted: January 6, 2025

Published online: April 15, 2025

Processing time: 278 Days and 21.7 Hours

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a major microvascular complication of diabetes mellitus, leading to significant visual impairment and blindness among adults. Current treatment options are limited, making it essential to explore novel therapeutic strategies. Curcumol, a sesquiterpenoid derived from traditional Chinese medicine, has shown anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer properties, but its potential role in DR remains unclear.

To investigate the therapeutic effects of curcumol on the progression of DR and to elucidate the underlying molecular mechanisms, particularly its impact on the fat mass and obesity-associated (FTO) protein and the long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) MAF transcription factor G antisense RNA 1 (MAFG-AS1).

A streptozotocin-induced mouse model of DR was established, followed by treatment with curcumol. Retinal damage and inflammation were evaluated through histological analysis and molecular assays. Human retinal vascular endothelial cells were exposed to high glucose conditions to simulate diabetic environments in vitro. Cell proliferation, migration, and inflammation markers were assessed in curcumol-treated cells. LncRNA microarray analysis identified key molecules regulated by curcumol, and further experiments were conducted to confirm the involvement of FTO and MAFG-AS1 in the progression of DR.

Curcumol treatment significantly reduced blood glucose levels and alleviated retinal damage in streptozotocin-induced DR mouse models. In high-glucose-treated human retinal vascular endothelial cells, curcumol inhibited cell proliferation, migration, and inflammatory responses. LncRNA microarray analysis identified MAFG-AS1 as the most upregulated lncRNA following curcumol treatment. Mechanistically, FTO demethylated MAFG-AS1, stabilizing its expression. Rescue experiments demonstrated that the protective effects of curcumol against DR were mediated through the FTO/MAFG-AS1 signaling pathway.

Curcumol ameliorates the progression of DR by modulating the FTO/MAFG-AS1 axis, providing a novel therapeutic pathway for the treatment of DR. These findings suggest that curcumol-based therapies could offer a promising alternative for managing this debilitating complication of diabetes.

Core Tip: This groundbreaking discovery led to the identification of a previously unknown signaling pathway involving curcumol, fat mass and obesity-associated protein, and MAF transcription factor G antisense RNA 1 in diabetic retinopathy. The elucidation of this molecular cascade enhanced our understanding of the therapeutic mechanisms of curcumol, revealing potential molecular targets for developing more targeted interventions to treat or prevent retinal complications associated with diabetes.

- Citation: Rong H, Hu Y, Wei W. Curcumol ameliorates diabetic retinopathy via modulating fat mass and obesity-associated protein-demethylated MAF transcription factor G antisense RNA 1. World J Diabetes 2025; 16(4): 97201

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v16/i4/97201.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v16.i4.97201

Diabetes frequently leads to a microvascular complication known as diabetic retinopathy (DR), which is a significant contributor to visual impairment and blindness among adults of working age[1]. This condition underscores the critical vascular damage associated with chronic hyperglycemia characteristic of diabetes. DR is marked by a spectrum of pathological features including microaneurysms, punctate and patchy hemorrhages, and intraretinal microvascular abnormalities. The etiology of DR encompasses a variety of factors such as prolonged diabetes duration, chronic hyperglycemia, and hypertension[1]. Additionally, inflammatory processes and retinal neurodegenerative conditions are also implicated in the progression of this microvascular complication. These contributory elements highlight the complex pathophysiology underlying DR, which remains a leading cause of visual disability in patients with diabetes[2]. Investigating the alterations and molecular signaling pathways associated with DR could facilitate the identification of potential therapeutic targets. Understanding these pathways is crucial for developing interventions that could prevent, halt, or reverse the progression of DR, thereby reducing the burden of this severe complication among patients with diabetes. Such research is essential for enhancing clinical outcomes and improving the quality of life for affected individuals.

Curcumol is a sesquiterpenoid compound derived from plants of the Zingiberaceae family, known for its diverse pharmacological effects. This compound effectively reduces inflammation and has been used to treat conditions such as psoriasis, atrophic gastritis, and asthma[3-5]. Moreover, curcumol helps prevent the progression of liver fibrosis by inhibiting cell apoptosis[6]. Its broad therapeutic properties make it a valuable candidate for further pharmaceutical development. In oncology research, curcumol has demonstrated significant potential in inhibiting the malignant progression of various cancers, including breast[7], prostate[8], and colorectal cancers[9]. Its mechanisms of action include suppression of tumor cell growth, migration, and invasion; interference with the cell cycle, and promotion of apoptosis. These multifaceted actions highlight curcumol’s capabilities as a promising anticancer agent across a spectrum of oncological applications. However, the impact of curcumol on DR remains to be elucidated. Further research is needed to explore this potential therapeutic pathway and determine the efficacy of curcumol in the progression of DR.

This study aimed to explore the impact of curcumol on the progression of DR and to decipher the molecular mecha

Male C57BL/6J mice (specific pathogen-free grade), aged 5-6 weeks, were acquired from Hunan SJA Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd, Changsha, China, and housed in ventilated microisolator cages under controlled conditions (12-hour light-dark cycle, 50% ± 15% humidity, and a temperature of 22 °C ± 2 °C). Upon arrival, mice were prepared for either diabetes induction or assignment as nondiabetic controls. Diabetes was induced at 6 weeks of age via intraperitoneal injections of STZ, dissolved in sodium citrate buffer (pH 4.3), at a dosage of 50 mg/kg body weight for 5 consecutive days. Mice in the control group were injected with an equal volume of sodium citrate buffer. Diabetes onset was confirmed with blood glucose levels exceeding 16.7 mmol/L. The mice were categorized into three groups (n = 5-7 each): nondiabetic controls, diabetic controls (type 1 diabetes, T1D), and diabetic mice treated with curcumol (T1D + curcumol). Curcumol, with a purity exceeding 98%, was sourced from Guizhou Dida Technology Co., Ltd. A stock solution was prepared using ddH2O as a solvent and diluted with phosphate-buffered saline to create the working solution. The T1D + curcumol group received oral administration of curcumol at 30 mg/kg daily for 12 weeks. All mice were fed a standard chow diet. Body weight and glucose levels were assessed every four weeks, with weekly records of food and water intake. The study adhered to the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and was approved by the Animal Ethics Board of the Affiliated Hospital of Yangzhou University, Huai’an Maternal and Child Health Care Center (ethics approval No. 202402884).

After 12 weeks of treatment with curcumol, the right eyeballs of the mice were harvested and immediately fixed in FAS eyeball fixation solution (G1109, Servicebio, Wuhan, China) for 24 h at room temperature. Following fixation, the tissues were dehydrated through a series of graded ethanol solutions and embedded in paraffin. Horizontal sections, 4-μm thick and including the optic nerve head, were prepared using a Leica RM2016 microtome (Heidelberg, Germany). These sections underwent hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining to assess morphological changes. The stained sections were systematically examined under a microscope to evaluate any histopathological changes associated with DR. This methodical approach allowed for a detailed analysis of curcumol’s effects on the structural integrity of retinal tissues.

Human retinal microvascular endothelial cells (BNCC 358978) were obtained from BeNa Culture Collection (Beijing, China) and cultured in T25 flasks under standard conditions: a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. MAFG-AS1 plasmids, small interfering RNAs targeting MAFG-AS1, methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3), METTL14, KIAA1429, Wilms’ tumor 1-associating protein, FTO, and anaplastic lymphoma kinase B homolog 5, as well as the corresponding negative controls, were obtained from GeneChem Biotechnology Company (Shanghai, China). Cell transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, United States) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. Following a 48-hour post-transfection period, cells were harvested for subsequent quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) or western blot analysis.

The PARIS kit (Invitrogen) was used to separate nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA, ensuring specific compartmentalization essential for precise molecular studies. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and U6 served as negative controls for cytoplasmic and nuclear RNA respectively, confirming the purity of the fractions obtained. This method enhances the accuracy of RNA-based evaluations, critical for reliable downstream molecular analyses.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and malondialdehyde (MDA) activities were assessed using specific assay kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China), following the manufacturer’s protocols. HRVECs were cultured in 24-well plates and subjected to various treatments. After treatment, cells were collected via centrifugation, and the supernatant was used for the assays. The cells were lysed via ultrasonication at a cell-to-extract ratio of 500:1 to 1000:1, followed by centrifugation to procure a clear supernatant. The optical density of the resulting supernatants was measured at a wavelength of 490 nm to determine the enzymatic activities of LDH and MDA, which are indicators of cellular damage and oxidative stress, respectively. This approach facilitated precise quantification of these biomarkers, reflecting cellular responses under different treatment conditions.

Cell proliferation was assessed using the methyl tetrazolium (MTT) assay, which involves the conversion of MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide, Molecular Probes, OR, United States] to a formazan product. The protocol was as follows: Each well’s medium was replaced with 100 μL of fresh medium, to which 10 μL of a 12 mmol/L MTT solution was added. The plates were then incubated for 4 h at 37 °C. Subsequently, the medium was discarded, leaving approximately 25 μL in each well. Thereafter, 50 μL of dimethyl sulfoxide was added to dissolve the formazan crystals, with thorough mixing. After a further 10 min of incubation at 37 °C, the absorbance at 540 nm was measured using a SpectraMax®M2 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, United States). This method allowed for quantitative analysis of cell proliferation by measuring the optical density, indicative of cell viability.

Human retinal microvascular endothelial cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of approximately 2000 cells per well. Following cell attachment, the culture medium was supplemented with an extracellular matrix containing 20% fetal bovine serum. After a 2-week incubation period, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min, followed by staining with crystal violet (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) for 15 min. Images of each well, containing more than 50 cells, were captured and observed using a phase-contrast microscope.

Total RNA was isolated from the treated HRVECs using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, United States), following which it was reverse transcribed into complementary DNA using a reverse transcription kit (Roche, Germany). qPCR was conducted using a Roche LightCycler480 system (Roche, Germany) to amplify the target mRNA sequences. The expression levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor α were quantitatively analyzed and normalized to the expression of the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. This normalization helped in mitigating any potential discrepancies arising from variable RNA input or complementary DNA synthesis inefficiencies, thereby ensuring the reliability of the comparative expression analyses across different samples. The primers used in this study are shown in Table 1.

| Gene name | Primer sequences (5’-3’) |

| MAFG-AS1 | Forward GAAGGTGTTCCGTGGTCAGT |

| Reverse GATGAGTGTGCGGAGTGAGA | |

| mIL-6 | Forward TAACAGATAAGCTGGAGTC |

| Reverse TAGGTTTGCCGAGTAGA | |

| mIL-8 | Forward GGTGAAGGCTACTGTTGG |

| Reverse CTGGAGTCCCGTAGAAAA | |

| mMCP-1 | Forward GGGTCCAGACATACATTAA |

| Reverse ACGGGTCAACTTCACATT | |

| IL-1β | Forward GGCTGCTCTGGGATTCTCTT |

| Reverse ATTTCACTGGCGAGCTCAGG | |

| IL-6 | Forward TTTTGGTGTTGTGCAAGGGTC |

| Reverse ATCGCTCCCTCTCCCTGTAA | |

| TNF α | Forward TGGGATCATTGCCCTGTGAG |

| Reverse GGTGTCTGAAGGAGGGGGTA | |

| FTO | Forward ACGGGTCAACTTCACATT |

| Reverse AGGAAGGTCTCACAAGCAGC | |

| GAPDH | Forward ATGGGACGATGCTGGTACTGA |

| Reverse TGCTGACAACCTTGAGTGAAAT | |

| U6 | Forward CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA |

| Reverse AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGT |

Protein extractions from tissues and cells were performed using radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (R0010, Solarbio) supplemented with phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (P0100, Solarbio). Protein concentrations were measured using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Cat No. PC0020, Solarbio), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Subsequently,

To evaluate the migration of human retinal microvascular endothelial cells, 8-μm-pore-size Transwell BD Matrigel chambers (Costar 3470, Corning, NY, United States) were used. Cells were seeded in the upper chamber containing

The degree of N6-methyladenosine (m6A) methylation in MAFG-AS1 was assessed using the Magna Methylated RNA immunoprecipitation (MeRIP) m6A Kit (Millipore), following the manufacturer’s instructions. For the MeRIP assays, an anti-m6A antibody (Abcam) was utilized. QRT-PCR was then employed to evaluate the enrichment of m6A-modified RNA, ensuring precise quantification of methylation levels. This methodological approach provides a robust framework for investigating RNA modifications.

Data are presented as mean ± SD and were processed using GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, United States). Statistical differences between two groups were evaluated using unpaired t-tests, whereas a one-way analysis of variance was used for comparisons among multiple groups. Statistical significance was established at P < 0.05.

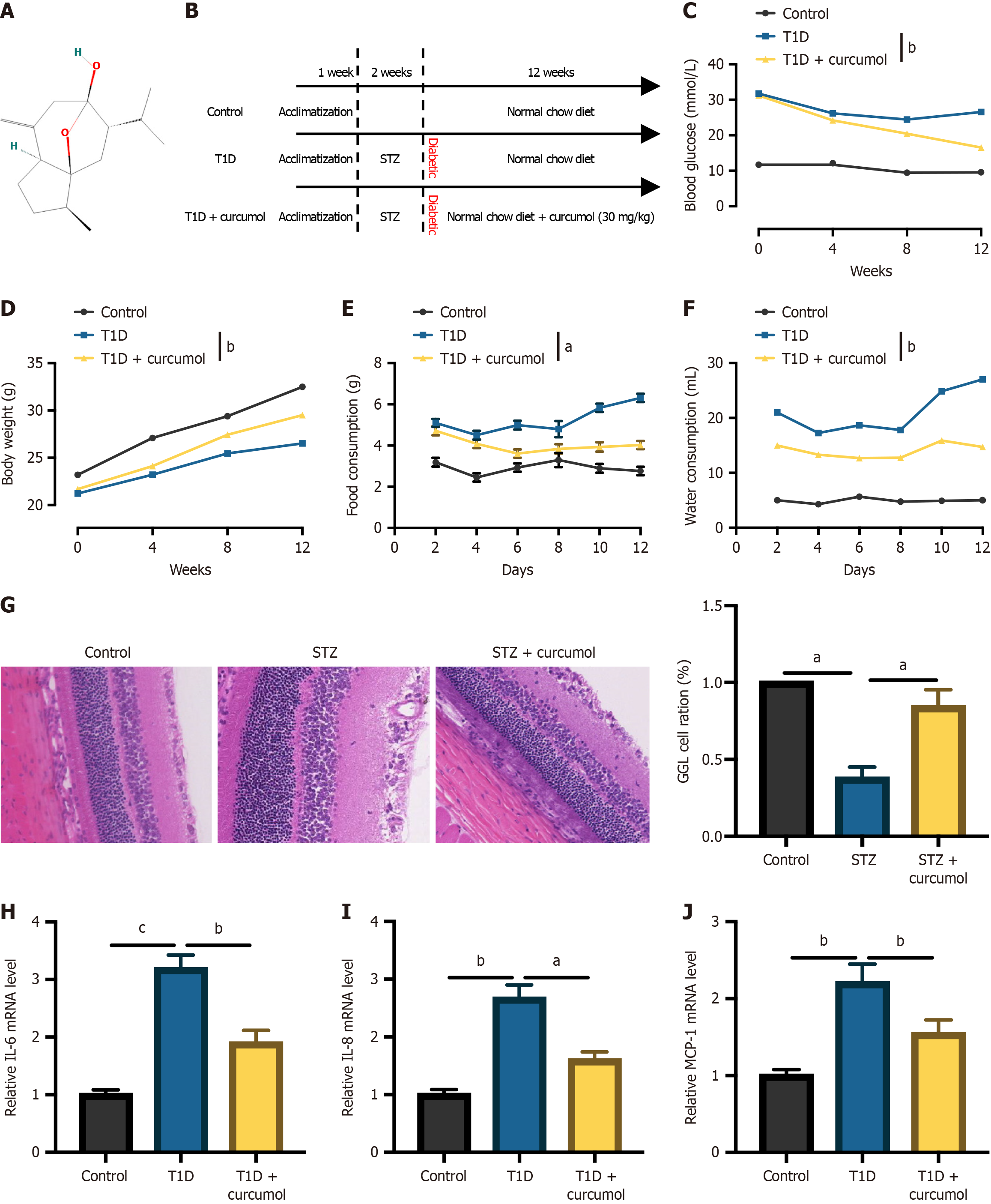

Our investigation began with the development of a diabetic mouse model through the administration of STZ. To ascertain the potential impact of curcumol on the progression of DR, we introduced curcumol treatment into STZ-induced DR mouse models. The molecular structure of curcumol is delineated (Figure 1A). The procedure for constructing the mouse model is illustrated in Figure 1B. To validate the successful construction of the model and assess the efficacy of curcumol, various physiological parameters were evaluated. As depicted in Figure 1C, blood glucose levels were significantly increased in T1D mice compared to control mice, whereas curcumol treatment notably mitigated these levels. Similar trends were observed for body weight (Figure 1D), food intake (Figure 1E), and water intake (Figure 1F). Additionally, we conducted histological analysis of retinal tissue sections using HE staining. Consistent with our findings, representative images of retinal morphology obtained through HE staining revealed decreased thicknesses of the total retina, inner layer, and middle layer in T1D mice compared to control mice. Remarkably, these thicknesses were significantly restored following curcumol treatment (Figure 1G). Furthermore, the mRNA expression levels of pro-inflammatory factors, including IL-6 (Figure 1H), IL-8 (Figure 1I), and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (Figure 1J), were significantly elevated in the retinal tissues of mice with DR. However, curcumol treatment effectively attenuated these increases.

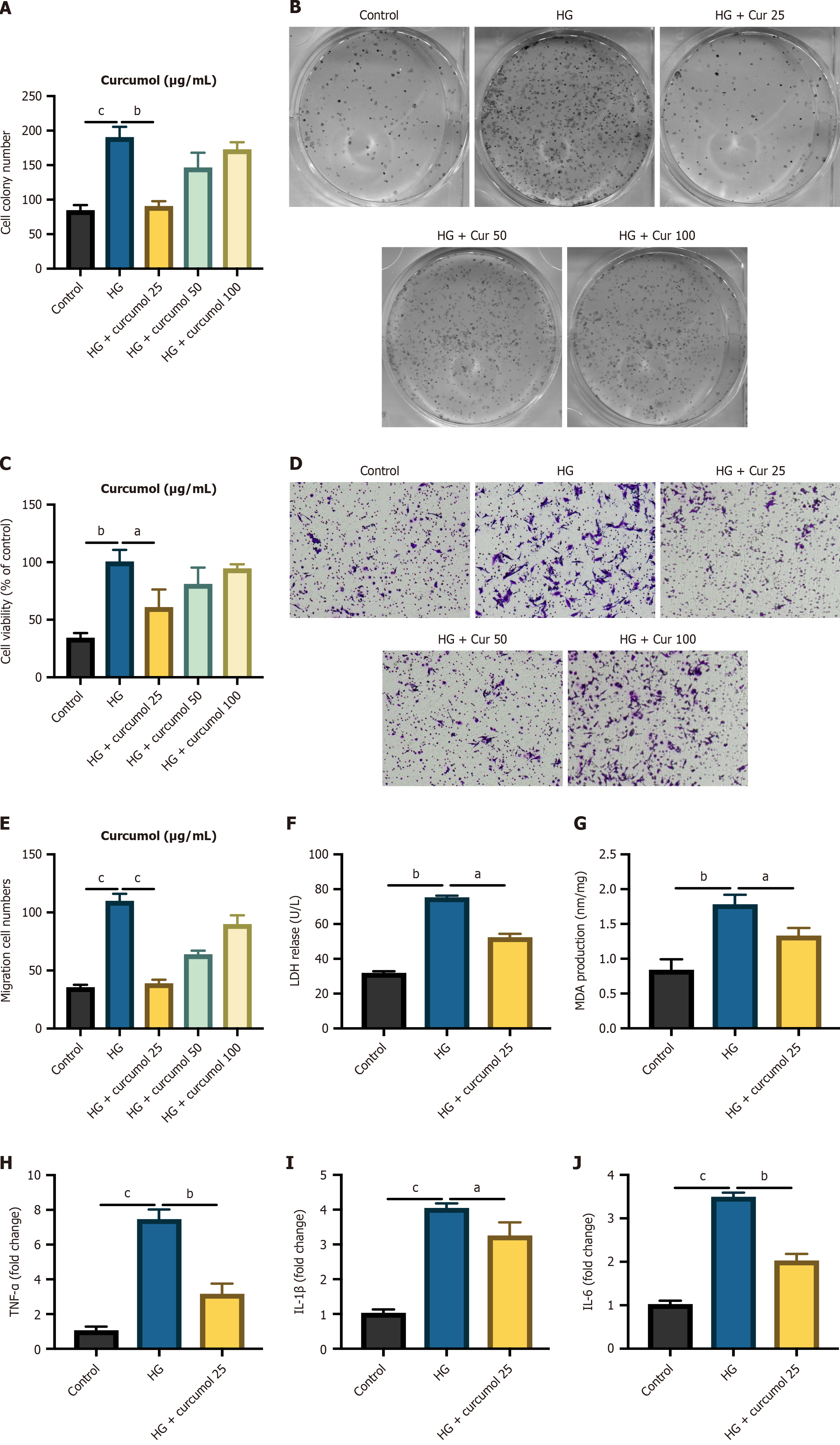

To further elucidate the impact of curcumol on retinal function within a diabetic cellular context, we exposed HG-HRVECs to varying concentrations of curcumol. The results of the MTT assay revealed a notable reduction in cell proliferation levels following curcumol treatment, with the most pronounced effect observed at a concentration of 25 μg/mL (Figure 2A). Subsequently, the cell colony assay corroborated these findings, demonstrating a significant decrease in cell viability upon treatment with curcumol at 25 μg/mL (Figure 2B and C). Consistent with these observations, the Transwell migration assay also indicated a similar trend (Figure 2C and D). To assess the protective effects of curcumol under HG conditions, we evaluated LDH leakage, MDA concentration, and mRNA expression of inflammation biomarkers (IL-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor α) in each experimental group. The release of LDH and MDA, both indicative of HG-induced cellular injury, was augmented following HG stimulation but ameliorated upon treatment with curcumol (Figure 2F and G). Furthermore, curcumol demonstrated a dose-dependent inhibition of HG-induced transcription of inflammatory cytokines (Figure 2H and J). Collectively, these results suggest that curcumol possesses the ability to mitigate the progression of DR.

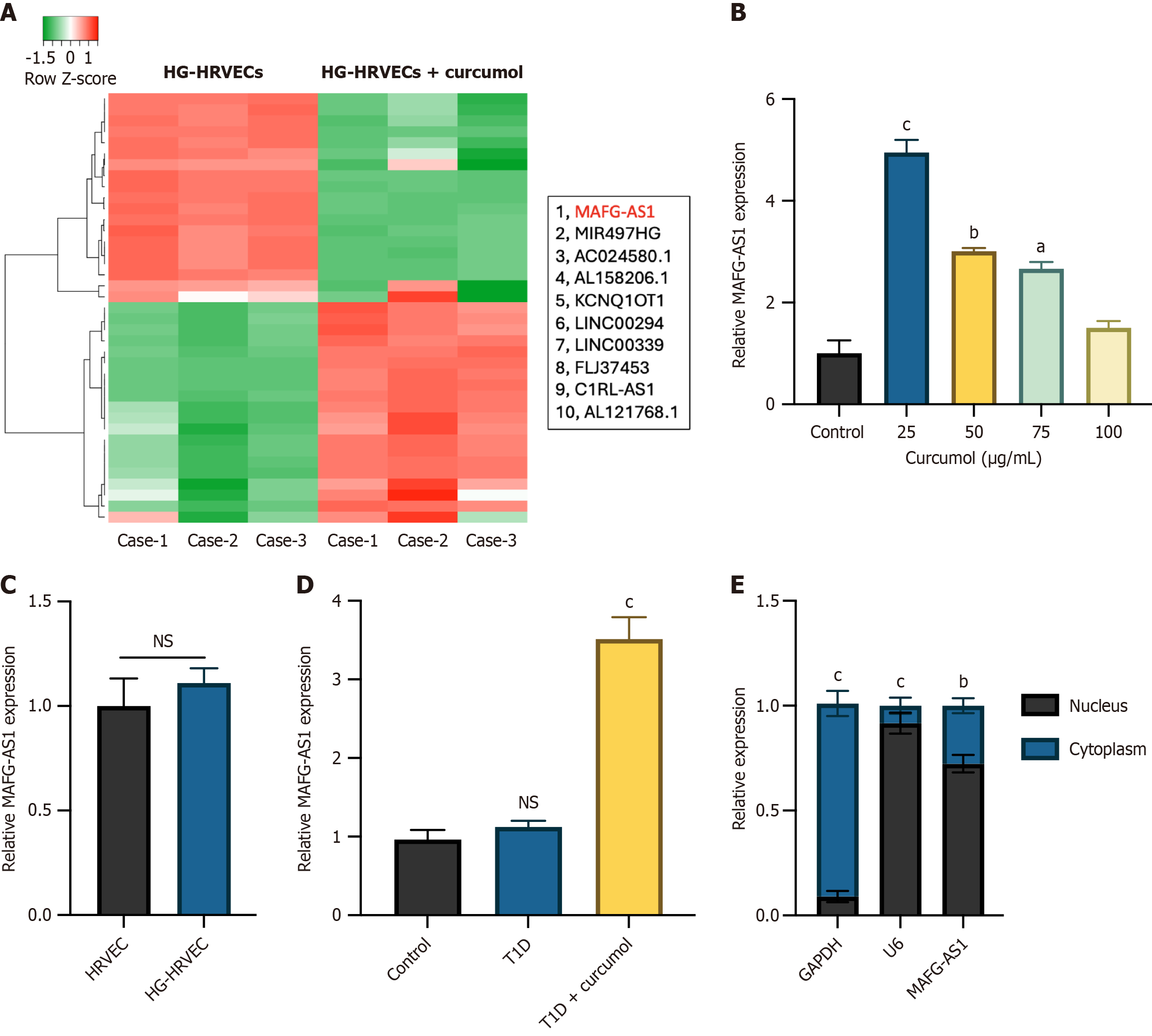

To gain deeper insights into the involvement of curcumol in DR, we investigated the underlying molecular mechanisms, with a specific focus on dysregulated lncRNAs. Utilizing lncRNA microarray analysis, we compared the expression profiles of lncRNAs in HG-HRVECs with those treated with curcumol at a concentration of 25 μg/mL. The top 10 significantly upregulated lncRNAs were identified and presented (Figure 3A), revealing MAFG-AS1 as the most markedly upregulated lncRNA. This upregulation of MAFG-AS1 was further validated by assessing its expression in HGHRVECs treated with various concentrations of curcumol (Figure 3B). Intriguingly, the expression level of MAFG-AS1 in HRVECs was comparable to that in HG-HRVECs, suggesting that the upregulation of MAFG-AS1 was specifically induced by curcumol treatment (Figure 3C). Moreover, the in vivo analysis demonstrated a similar upregulation of MAFG-AS1 in retinal tissues obtained from control mice, T1D mice, and T1D mice subjected to curcumol treatment (Figure 3D). Subsequent cellular distribution assays revealed that MAFG-AS1 predominantly localized within the cell nucleus (Figure 3E), indicating its potential functional relevance in the progression of DR.

In this study, we proceeded to validate the biological significance of MAFG-AS1 through experimental manipulation using curcumol-treated HG-HRVECs. To achieve this, we constructed experimental cell models by introducing curcumol alone or in combination with small interfering-MAFG-AS1 into HG-HRVECs, with the successful construction of these models confirmed via qRT-PCR analysis (Figure 4A). Subsequent assessment of cell proliferation levels through the MTT assay revealed a significant decrease following curcumol treatment, whereas this effect was attenuated upon the knockdown of MAFG-AS1 (Figure 4B). Moreover, the cell colony assay yielded consistent results, demonstrating a notable decline in cell viability upon curcumol treatment, which was rescued by MAFG-AS1 knockdown in HG-HRVECs (Figure 4C and D). Similarly, the Transwell migration assay indicated a parallel trend (Figure 4E and F). The release of LDH and MDA was attenuated following curcumol treatment but elevated upon MAFG-AS1 knockdown (Figure 4G and H). Furthermore, the inhibitive effects of curcumol on HG-induced transcription of inflammatory cytokines were reversed by MAFG-AS1 knockdown (Figure 4I-K). These findings collectively indicate that curcumol may exert its protective effects against the progression of DR through the modulation of MAFG-AS1 expression.

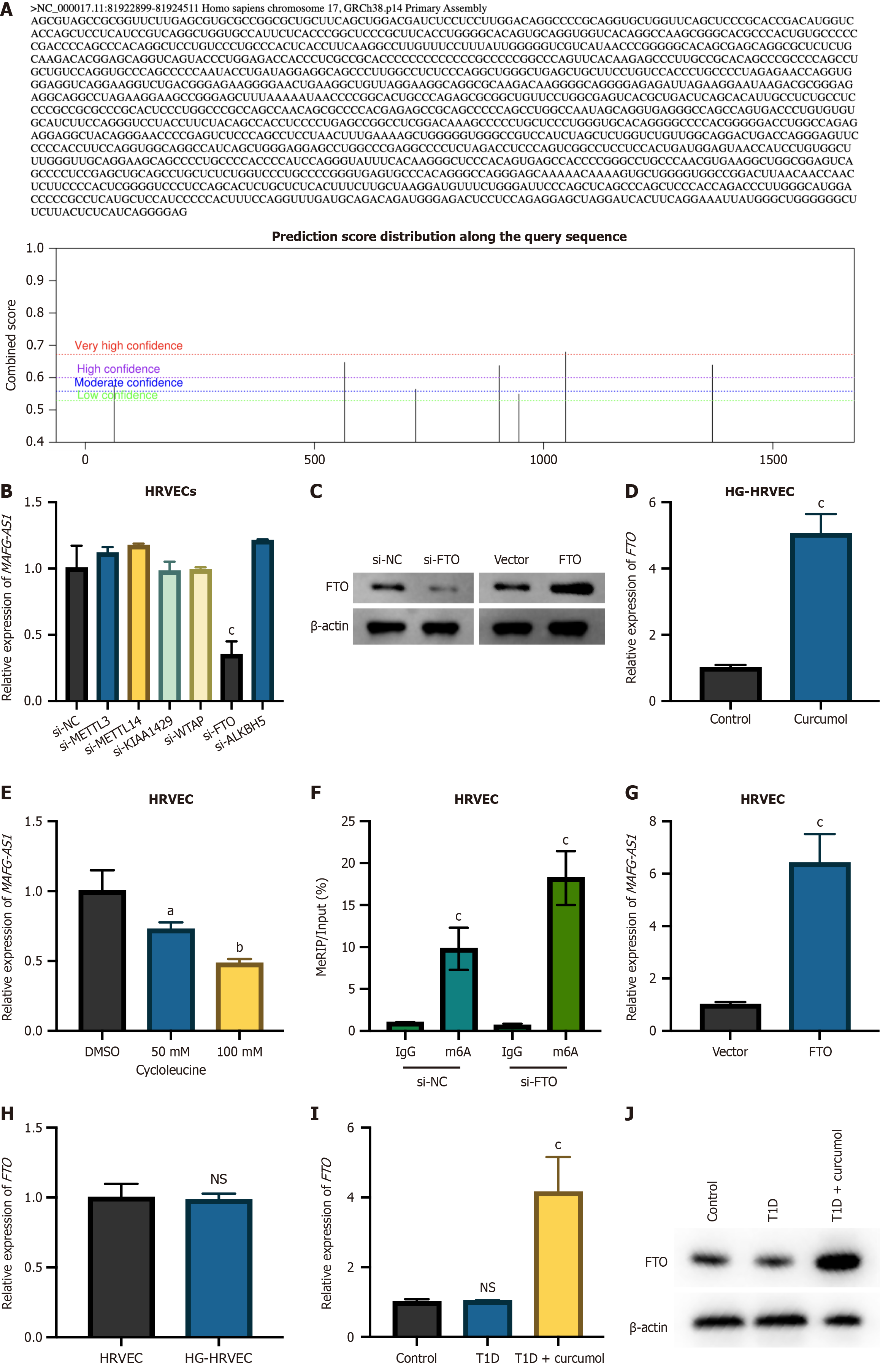

Recent developments have highlighted the critical importance of m6A modifications in regulating RNA expression and advancing DR[10]. Using the SRAMP prediction tool (http://www.cuilab.cn/sramp), multiple m6A modification sites were identified on the MAFG-AS1 transcript (Figure 5A). Analysis of MAFG-AS1 expression after silencing common m6A modifiers (METTL3, METTL14, KIAA1429, Wilms’ tumor 1-associating protein, FTO, anaplastic lymphoma kinase B homolog 5) showed a significant decrease in MAFG-AS1 levels following FTO knockdown (Figure 5B). The efficacy of FTO knockdown or overexpression was verified (Figure 5C), revealing that FTO overexpression led to increased MAFG-AS1 levels (Figure 5D). Treatment with the m6A synthesis inhibitor cycloleucine caused a dose-dependent increase in MAFG-AS1 RNA levels (Figure 5E). These findings suggest that FTO regulates the m6A modification of MAFG-AS1 in HRVECs. MeRIP-PCR analysis further confirmed that FTO silencing enhanced the m6A modification of MAFG-AS1 (Figure 5F). Additionally, the impact of curcumol on FTO expression was assessed in HRVECs under HG and normal conditions. Curcumol significantly increased FTO expression exclusively under HG conditions (Figure 5G), with no effect observed in normal HRVECs or untreated HG-HRVECs (Figure 5H). In vivo experiments reinforced these findings. FTO expression was substantially higher in diabetic (T1D) mice treated with curcumol compared to both untreated T1D mice and control mice (Figure 5I and J). These findings indicate that curcumol specifically induces FTO upregulation, contributing to its therapeutic effects against diabetic complications.

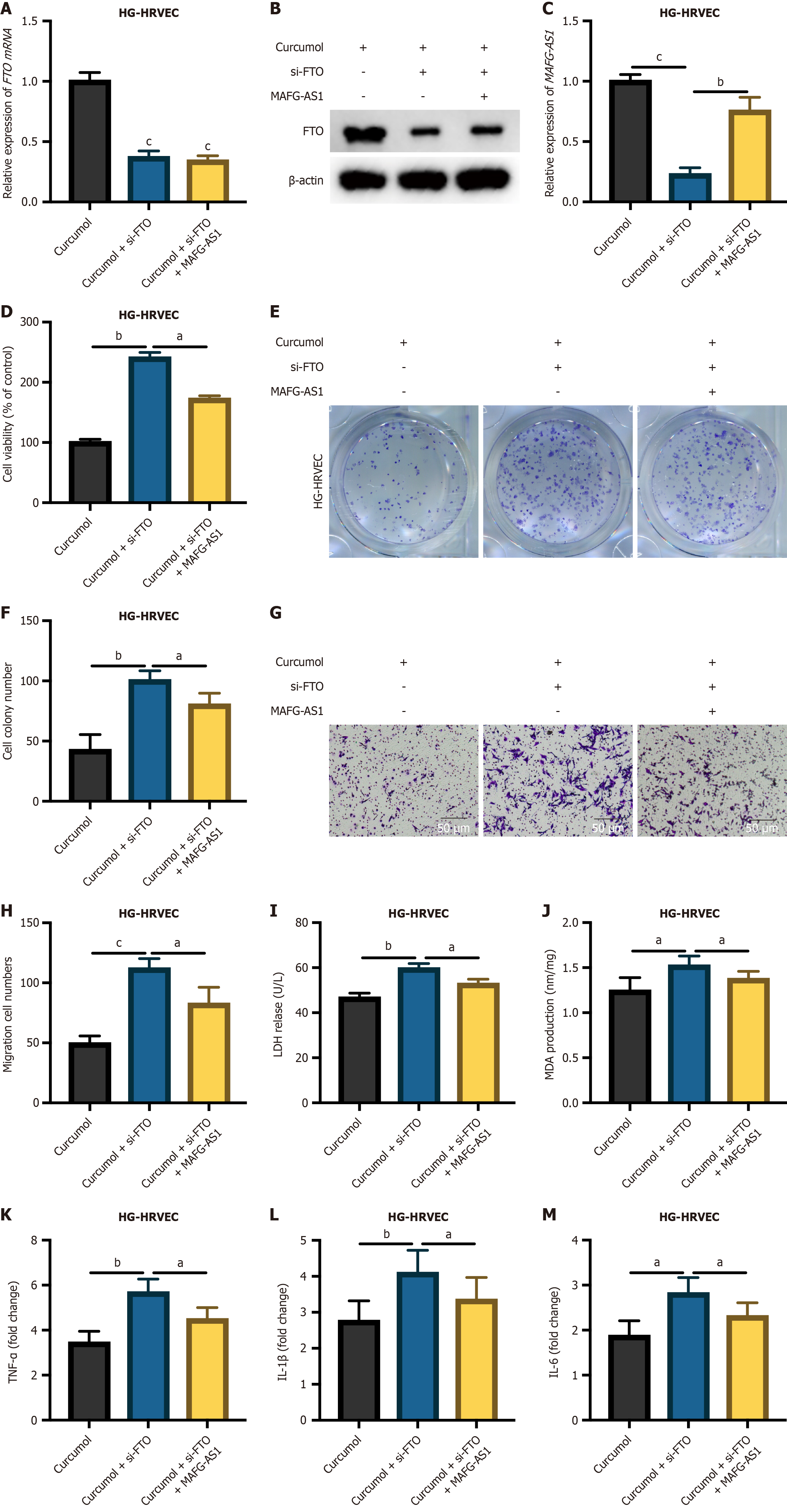

To evaluate whether curcumol exerts its inhibitory effects on DR progression via the FTO-demethylated MAFG-AS1 pathway, we further established HG-HRVEC cell models, as depicted in Figure 6A-C, with generation efficiencies duly assessed. The MTT assay revealed a significant reduction in the proliferation of curcumol-treated HG-HRVECs upon FTO knockdown, and this inhibitory effect was rescued by MAFG-AS1 (Figure 6D). Subsequently, the cell colony assay yielded consistent findings, demonstrating a noteworthy decrease in cell viability upon FTO knockdown in curcumol-treated HG-HRVECs, which was mitigated by MAFG-AS1 (Figure 6E and F). Consistent results were observed in the Transwell migration assay (Figure 6G and H). The release of LDH and MDA was increased following FTO knockdown in curcumol-treated HG-HRVECs but restored upon MAFG-AS1 overexpression (Figure 6I and J). The promotive effects of FTO knockdown on inflammatory cytokine production in curcumol-treated HG-HRVECs were reversed by MAFG-AS1 overexpression (Figure 6K-M). Taken together, these results suggest that curcumol may exert its protective effects against the progression of DR through modulation of the FTO/MAFG-AS1 axis.

DR is a prevalent complication of diabetes mellitus and a leading cause of blindness in middle-aged and elderly populations worldwide[11]. With a vast number of individuals at risk and a high likelihood of blindness and disability, DR imposes significant personal hardships and psychological distress on patients. Additionally, it places a considerable economic strain on societies, emphasizing the urgent need for effective therapeutic and management strategies to address this public health challenge. Traditional Chinese medicine, with its heritage spanning thousands of years, has been shown to have significant therapeutic effects on diabetes and its complications. Research has consistently demonstrated that it can effectively reduce blood glucose levels and improve lipid profiles along with other metabolic indicators[12]. Additionally, numerous studies have confirmed that Chinese herbal therapies provide effective interventions for DR, offering a promising alternative to conventional treatments by enhancing patient outcomes and managing symptoms effectively[13,14]. Given the significant impact of DR on individuals’ quality of life and its broader socioeconomic implications, there is a pressing need for effective therapeutic approaches. In this study, we explored the potential role of curcumol in mitigating the progression of DR, focusing on its influence at the molecular level, specifically through the modulation of lncRNAs. Our findings provide new insights into the therapeutic potential of curcumol and its mechanism of action via the FTO/MAFG-AS1 axis.

The physiological role of lncRNAs in disease progression has attracted increasing attention, particularly in the context of their function as competitive endogenous RNAs[15-18]. Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that lncRNAs are involved in essential physiological functions in various animals[19,20]. Recent genetic research also indicates a significant role for lncRNAs in the development of DR, highlighting their potential as targets for therapeutic strategies[21,22]. This body of evidence underscores the complex roles these molecules play in modulating cellular mechanisms and disease pathways. To better understand the role of curcumol in DR progression, in our study, we hypothesized that curcumol exerts its protective effects in DR by modulating lncRNA expression. Through lncRNA microarray analysis, we identified MAFG-AS1 as the most significantly upregulated lncRNA following curcumol treatment. Importantly, we demonstrated that the biological functions of MAFG-AS1 mirrored those of curcumol, suggesting that MAFG-AS1 plays a central role in mitigating the progression of DR.

Our study further investigated the upstream regulation of MAFG-AS1. M6A methylation is a key post-transcriptional modification involved in RNA metabolism and has been shown to affect the stability and function of both mRNAs and lncRNAs[23-25]. Our results found that MAFG-AS1 expression could be positively regulated by FTO. FTO, a member of the Fe2+/2-oxoglutarate-dependent AlkB dioxygenase family, was the first enzyme identified as an m6A demethylase in eukaryotes and been identified to play crucial roles in multiple biological processes[26-29]. However, its role in DR remains unclear. Our rescue experiments confirmed that FTO stabilizes MAFG-AS1 through demethylation. This novel finding highlights the FTO/MAFG-AS1 axis as a critical pathway through which curcumol exerts its protective effects on DR.

Our in vivo and in vitro results consistently demonstrated that curcumol treatment alleviated key pathological features of DR, including retinal damage, inflammation, and vascular dysfunction. Curcumol significantly reduced HG-induced proliferation and migration of HRVECs, as well as inflammation. These protective effects were mediated through the upregulation of MAFG-AS1, with FTO acting as a crucial upstream regulator. By modulating the methylation status of MAFG-AS1, FTO enhances its stability and expression, thereby contributing to the inhibition of DR progression.

Our study uncovers a novel regulatory pathway involving curcumol, FTO, and MAFG-AS1 that attenuates the progression of DR. These findings not only provide a deeper understanding of curcumol’s molecular mechanisms but also suggest new therapeutic targets for DR. Future studies are necessary to further elucidate the physiological functions of MAFG-AS1 and to explore the broader implications of the FTO/MAFG-AS1 axis in other complications of diabetes. By expanding our understanding of these molecular pathways, we hope to develop more effective strategies for the prevention and treatment of DR.

We thank all participants involved in the original study and all investigators for sharing the data.

| 1. | Lechner J, O'Leary OE, Stitt AW. The pathology associated with diabetic retinopathy. Vision Res. 2017;139:7-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 321] [Article Influence: 40.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Altmann C, Schmidt MHH. The Role of Microglia in Diabetic Retinopathy: Inflammation, Microvasculature Defects and Neurodegeneration. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 285] [Article Influence: 40.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lv M, Shao J, Jiang F, Liu J. Curcumol may alleviate psoriasis-like inflammation by inhibiting keratinocyte proliferation and inflammatory gene expression via JAK1/STAT3 signaling. Aging (Albany NY). 2021;13:18392-18403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ma X, Kong L, Zhu W, Wang Y, Zhang Z, Tian Y. Curcumol Undermines SDF-1α/CXCR4/NF-κB Signaling Pathway to Suppress the Progression of Chronic Atrophic Gastritis (CAG) and Gastric Cancer. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2022;2022:3219001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Jia S, Guo P, Lu J, Huang X, Deng L, Jin Y, Zhao L, Fan X. Curcumol Ameliorates Lung Inflammation and Airway Remodeling via Inhibiting the Abnormal Activation of the Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway in Chronic Asthmatic Mice. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2021;15:2641-2651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chen G, Wang Y, Li M, Xu T, Wang X, Hong B, Niu Y. Curcumol induces HSC-T6 cell death through suppression of Bcl-2: involvement of PI3K and NF-κB pathways. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2014;65:21-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ning L, Ma H, Jiang Z, Chen L, Li L, Chen Q, Qi H. Curcumol Suppresses Breast Cancer Cell Metastasis by Inhibiting MMP-9 Via JNK1/2 and Akt-Dependent NF-κB Signaling Pathways. Integr Cancer Ther. 2016;15:216-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sheng W, Xu W, Ding J, Li L, You X, Wu Y, He Q. Curcumol inhibits the malignant progression of prostate cancer and regulates the PDK1/AKT/mTOR pathway by targeting miR9. Oncol Rep. 2021;46:246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yu D, Liu H, Qin J, Huangfu M, Guan X, Li X, Zhou L, Dou T, Liu Y, Wang L, Fu M, Wang J, Chen X. Curcumol inhibits the viability and invasion of colorectal cancer cells via miR-30a-5p and Hippo signaling pathway. Oncol Lett. 2021;21:299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kumari N, Karmakar A, Ahamad Khan MM, Ganesan SK. The potential role of m6A RNA methylation in diabetic retinopathy. Exp Eye Res. 2021;208:108616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Teo ZL, Tham YC, Yu M, Chee ML, Rim TH, Cheung N, Bikbov MM, Wang YX, Tang Y, Lu Y, Wong IY, Ting DSW, Tan GSW, Jonas JB, Sabanayagam C, Wong TY, Cheng CY. Global Prevalence of Diabetic Retinopathy and Projection of Burden through 2045: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2021;128:1580-1591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 1025] [Article Influence: 256.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Tian J, Jin D, Bao Q, Ding Q, Zhang H, Gao Z, Song J, Lian F, Tong X. Evidence and potential mechanisms of traditional Chinese medicine for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21:1801-1816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ai X, Yu P, Hou Y, Song X, Luo J, Li N, Lai X, Wang X, Meng X. A review of traditional Chinese medicine on treatment of diabetic retinopathy and involved mechanisms. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;132:110852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Huai B, Huai B, Su Z, Song M, Li C, Cao Y, Xin T, Liu D. Systematic evaluation of combined herbal adjuvant therapy for proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1157189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Herman AB, Tsitsipatis D, Gorospe M. Integrated lncRNA function upon genomic and epigenomic regulation. Mol Cell. 2022;82:2252-2266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 382] [Article Influence: 127.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ali T, Grote P. Beyond the RNA-dependent function of LncRNA genes. Elife. 2020;9:e60583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 39.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ferrè F, Colantoni A, Helmer-Citterich M. Revealing protein-lncRNA interaction. Brief Bioinform. 2016;17:106-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 323] [Cited by in RCA: 513] [Article Influence: 51.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Jarroux J, Morillon A, Pinskaya M. History, Discovery, and Classification of lncRNAs. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;1008:1-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 461] [Cited by in RCA: 613] [Article Influence: 76.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kopp F, Mendell JT. Functional Classification and Experimental Dissection of Long Noncoding RNAs. Cell. 2018;172:393-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1719] [Cited by in RCA: 2635] [Article Influence: 439.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Schmitz SU, Grote P, Herrmann BG. Mechanisms of long noncoding RNA function in development and disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73:2491-2509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 768] [Cited by in RCA: 843] [Article Influence: 93.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Chang X, Zhu G, Cai Z, Wang Y, Lian R, Tang X, Ma C, Fu S. miRNA, lncRNA and circRNA: Targeted Molecules Full of Therapeutic Prospects in the Development of Diabetic Retinopathy. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:771552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Geng M, Liu W, Li J, Yang G, Tian Y, Jiang X, Xin Y. LncRNA as a regulator in the development of diabetic complications. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2024;15:1324393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chen Y, Lin Y, Shu Y, He J, Gao W. Interaction between N(6)-methyladenosine (m(6)A) modification and noncoding RNAs in cancer. Mol Cancer. 2020;19:94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 40.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zaccara S, Ries RJ, Jaffrey SR. Reading, writing and erasing mRNA methylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20:608-624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1100] [Cited by in RCA: 1625] [Article Influence: 270.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Huang H, Weng H, Chen J. m(6)A Modification in Coding and Non-coding RNAs: Roles and Therapeutic Implications in Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2020;37:270-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 434] [Cited by in RCA: 882] [Article Influence: 176.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Chen B, Ye F, Yu L, Jia G, Huang X, Zhang X, Peng S, Chen K, Wang M, Gong S, Zhang R, Yin J, Li H, Yang Y, Liu H, Zhang J, Zhang H, Zhang A, Jiang H, Luo C, Yang CG. Development of cell-active N6-methyladenosine RNA demethylase FTO inhibitor. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:17963-17971. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 354] [Article Influence: 27.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Tao L, Mu X, Chen H, Jin D, Zhang R, Zhao Y, Fan J, Cao M, Zhou Z. FTO modifies the m6A level of MALAT and promotes bladder cancer progression. Clin Transl Med. 2021;11:e310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Li J, Han Y, Zhang H, Qian Z, Jia W, Gao Y, Zheng H, Li B. The m6A demethylase FTO promotes the growth of lung cancer cells by regulating the m6A level of USP7 mRNA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;512:479-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 29.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Wang Y, Li M, Zhang L, Chen Y, Zhang S. m6A demethylase FTO induces NELL2 expression by inhibiting E2F1 m6A modification leading to metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2021;21:367-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |