Published online Apr 15, 2025. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v16.i4.102970

Revised: January 4, 2025

Accepted: February 5, 2025

Published online: April 15, 2025

Processing time: 116 Days and 4.5 Hours

Gut microbiota play a crucial role in metabolic diseases, including type 2 diabetes (T2DM) and hyperuricemia (HUA). One-third of uric acid is excreted into the intestinal tract and further metabolized by gut microbiota. Thus, the gut micro

To investigate dysbiosis in patients with T2DM and HUA, and the effect of em

In this age and sex-matched, case-control study, we recruited 30 patients with T2DM and HUA; 30 with T2DM; and 30 healthy controls at the Henan Provincial People’s Hospital between February 2019 and August 2023. Nine patients with T2DM and HUA were treated with empagliflozin for three months. Gut microbiota profiles were assessed using the 16S rRNA gene.

Patients with T2DM and HUA had the highest total triglycerides (1.09 mmol/L in heathy control vs 1.56 mmol/L in T2DM vs 2.82 mmol/L in T2DM + HUA) and uric acid levels (302.50 μmol/L in heathy control vs 288.50 μmol/L in T2DM vs 466.50 μmol/L in T2DM + HUA) among the three groups. The composition of the gut microbiota differed significantly between patients with T2DM and HUA, and those with T2DM/healthy controls (P < 0.05). Notably, patients with T2DM and HUA demonstrated a deficiency of uric acid-degrading bacteria such as Romboutsia, Blautia, Clostridium sensu stricto 1 (P < 0.05). Empagliflozin treatment was associated with significantly reduced serum uric acid levels and purine metabolism-related pathways and genes in patients with T2DM and HUA (P < 0.05).

Gut dysbiosis may contribute to the pathogenesis of HUA in T2DM, and empagliflozin may partly restore the gut microbiota related to uric acid metabolism.

Core Tip: Patients with type 2 diabetes (T2DM) have a significantly higher prevalence of hyperuricemia (HUA) than non-diabetic patients and are more likely to suffer from cardiovascular diseases. In recent years, the gut microbiota has been shown to play a crucial role in metabolic diseases, including T2DM and HUA. Thus, the gut microbiota may be a new therapeutic target for HUA. Empagliflozin significantly lowers serum uric acid levels and contributes to cardiovascular benefits which are partly attributed to altered gut microbiota. This study revealed that empagliflozin administered to patients with characteristic dysbiosis due to T2DM and HUA, may have gut microbiota involved in purine metabolism partially restored.

- Citation: Deng XR, Zhai YJ, Shi XY, Tang SS, Fang YY, Heng HY, Zhao LY, Yuan HJ. Characteristic dysbiosis in patients with type 2 diabetes and hyperuricemia, and the effect of empagliflozin on gut microbiota. World J Diabetes 2025; 16(4): 102970

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v16/i4/102970.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v16.i4.102970

Hyperuricemia (HUA) is a metabolic disorder characterized by abnormal purine metabolism, resulting in a sequence of tissue damage such as gout, atherosclerosis, and chronic kidney disease[1]. The global prevalence of HUA has risen to 15%-20%[2,3], making it the second most common metabolic disease after type 2 diabetes (T2DM)[4]. Emerging evidence indicates that gut microbiota play an important role in the pathogenesis of T2DM and cardiovascular diseases[5,6]. Among the commonly reported findings, the genera of Ruminococcus, Fusobacterium, and Blautia were abundant in patients with T2DM with a low diversity[7]. In patients with T2DM, the risk for atherosclerosis which is associated with elevated serum uric acid levels is partly driven by gut microbiota[8]. Radioisotope studies involving healthy individuals revealed that approximately one-third of uric acid is excreted into the intestinal tract and further metabolized by the gut microbiota, a process that is doubled in proportion in patients with kidney disease[9]. Thus, gut microbiota is a new therapeutic target for HUA[4,9].

In patients with T2DM, empagliflozin, which is a selective inhibitor of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2, mitigates hyperglycemia via reducing renal glucose reabsorption and enhancing urinary glucose excretion[10]. In patients with or without T2DM, empagliflozin significantly lowers serum uric acid levels and contributes to cardiovascular benefits which are partly attributed to altered gut microbiota[11,12]. However, the association between empagliflozin treatment, uric acid metabolism, and gut microbiota remains unclear. Therefore, the aim of the study was to investigate gut dysbiosis and the effect of empagliflozin treatment on gut microbiota associated with purine metabolism in patients with T2DM with HUA.

The study approved by the Ethics Committee and Committee for Clinical Investigation of Henan Provincial People’s Hospital (Henan Province, China), and registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (No. ChiCTR1800018825 and No. ChiCTR2000030049) was performed following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent.

We consecutively recruited 30 patients with T2DM and HUA; 30 patients with T2DM; and 30 healthy controls at the Henan Provincial People’s Hospital between February 2019 and August 2023. The participants in the three groups were age and sex-matched. Patients were included on the basis of the following criteria: (1) 18 to 70 years of age; (2) T2DM was defined by the 1999 World Health Organization with the typical history of hyperglycemia without requiring for immediate insulin treatment or positive islet autoantibodies[6,13], and HUA was defined as individuals with a fasting serum uric acid level was higher than 420 μmol/L in men and 360 μmol/L in women[1]; and (3) No history of type 1 diabetes mellitus, immune disorders, or other severe diabetic complication diseases. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Secondary diabetes; (2) Infectious diseases; (3) Acute or chronic inflammatory disease; (4) Pregnancy; (5) Malignant tumors; (6) History of steroid or immunosuppressive drug use > 7 days; (7) History of treatment with prebiotics, probiotics, antibiotics, or any other medication that could potentially influence the gut microbiota for > 3 days in the previous three months; (8) A history of hepatic and renal malfuncting; (9) Gastrointestinal diseases; and (10) Gastro

Nine individuals with treatment-naive T2DM and HUA who participated in the case-control analysis were recruited for the intervention analysis. These nine participants were treated with empagliflozin (10 mg/day, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma, Ingelheim am Rhrin, Germany) for 3 months as previously described[12].

All patients with T2DM were educated on glycemic control. Data on health status, lifestyle, medical history, and medication use were obtained using standard questionnaires. Anthropometric and metabolic assessments were per

Statistical analyses were conducted using STATA (version 15.0; STATA Corp., College Station, TX, United States). Continuous variables are presented as the means ± SDs or medians with interquartile ranges for normal distribution data or non-normal distribution data, respectively. Categorical variables are presented as numbers (proportions). One-way analysis of variance or Kruskal-Wall is test was used to compare the differences between groups. Significant difference were adjusted by Bonferroni correction. The comparison in continuous variables before and after empagliflozin treatment were conducted using paired-sample t-tests or the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test.

Genomic DNA was extracted from fecal samples using the QIAamp Power Fecal Pro DNA kit (51804; QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). Gut microbiota in the fecal samples were profiled using 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing.

A polymerase chain reaction targeting the V3-V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was performed using forward (5’-CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3’) and reverse (5’-GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3’) primers[14]. Subsequent amplicon sequencing was performed on a MiSeq platform to generate paired-end reads of 300 base pairs each in length (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States).

Three batches of sequencing data were used in case-control analysis, and the sequences were analyzed using QIIME2 version 2023.2 respectively[15]. The adapters of the original sequences were removed using the “cutadapt” plugin of QIIME2. Sequences were then truncated with DADA2 and further filtered, denoised, cleared of chimeras, and merged to obtain the abundance and representative sequences of amplicon sequence variants (ASVs)[16]. Subsequently, the ASVs of the three batches were merged using the QIIME2. Representative sequences for ASVs were built into a phylogenetic tree using the core-metrics-phylogenetic pipeline in QIIME2 and assigned to taxonomy using SILVA database (release 138)[17]. Since the detection was carried out in different batches, the ComBatseq function of the R package was used to remove the batch effect (without adding grouping parameters) firstly. All samples were then randomly subsampled to equal depths of 9070 reads before the subsequent fecal microbiome analysis using QIIME2 diversity plugins.

In the intervention analysis, the sequences were analyzed using QIIME2 version 2023.2 as described above. All samples were randomly subsampled to equal depths of 23212 reads before the subsequent fecal microbiome analysis using QIIME2 diversity plugins.

The raw Illumina sequence data in this study are available in the sequence read archive at National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under accession No. SRP513322.

For the α-diversity, microbiome diversity was evaluated using the Shannon index, and the microbiome richness was evaluated by the number of observed ASVs using QIIME2 plugin diversity (-core-metrics-phylogenetic). For the analysis of β-diversity, QIIME2 plugin diversity (-core-metrics-phylogenetic) was used to perform the principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on Bray-Curtis distances. Also, the diversity plugin was used to perform the permutational multivariate analysis of variance test (999 tests) to test the significance of the differences of the gut microbiota structure between groups. The unsupervised partial least squares discrimination analysis (PLS-DA) was performed using R package mixomics[18]. We used LEfSe (R package lefser) to determine the ASVs that were significantly differentiated between groups.

The sparse correlation for composite data algorithm was used to calculate the correlation between ASVs in the case-control study with a sample co-occurrence rate greater than 10%, and the correlation value was converted into a correlation distance (1-correlation value). Then Ward clustering algorithm was then used to cluster R-package weighted correlation network analysis, and co-abundance groups (CAGs) were obtained. The CAG network was visualized in the Cytoscape (selection criteria: 1, P value < 0.05; 2, absolute value of r value > 0.3). Differences in CAGs between groups were tested using ordinary one-way analysis of variance test combined with Tukey’s multiple comparisons in the case-control analysis, and paired t test in the intervention study. GraphPad Prism 9 was used to visualize the differences in CAGs.

PICRUST2 was used to predict the metabolic functions of microbiota based on the representative sequences obtained by QIIME2 using the Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) and Meta CYC databases[19]. The different metabolic pathways between the groups were selected by performing ordinary one-way analysis of variance combined with Tukey’s multiple comparisons in case-control analysis, and paired t-test in the intervention analysis. GraphPad Prism 9 was used to visualized different pathways and KEGG Orthologys.

Thirty patients with T2DM and HUA, 30 patients with T2DM, and 30 healthy controls were age- and sex-matched (Table 1). Expectedly, the body mass index (BMI), waist-hip ratio, systolic blood pressure, fasting plasma glucose, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), and serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol were significantly higher in T2DM patients with or without HUA, than in healthy controls. The patients with T2DM and HUA had significantly higher serum uric acid levels.

| HC (n = 30) | T2DM (n = 30) | T2DM + HUA (n = 30) | P value (HC vs T2DM) | P value (HC vs T2DM + HUA) | P value (T2DM vs T2DM + HUA) | |

| Age (year), medians IQR | 36.5 (30.0, 48.0) | 36.0 (30.0, 48.0) | 35.5 (29.0, 48.0) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Male, n (%) | 21 (70) | 21 (70) | 21 (70) | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.33 ± 3.01 | 26.08 ± 3.41 | 27.96 ± 4.26 | 0.012 | < 0.001 | 0.139 |

| WHR | 0.87 ± 0.07 | 0.93 ± 0.08 | 0.95 ± 0.07 | 0.007 | < 0.001 | 1.000 |

| SBP (mmHg), medians IQR | 114.00 (110.00, 127.00) | 125.00 (115.00, 135.00) | 129.50 (120.00, 136.00) | 0.032 | < 0.001 | 0.203 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 73.43 ± 8.84 | 77.50 ± 9.96 | 81.73 ± 9.54 | 0.299 | 0.003 | 0.260 |

| FPG (mmol/L) | 5.01 ± 0.57 | 8.06 ± 3.33 | 8.20 ± 2.75 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 1.000 |

| HbA1c (%), medians IQR | 4.92 (4.60, 5.40) | 6.90 (6.20, 9.25) | 7.79 (6.32, 8.90) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 1.000 |

| TG (mmol/L), medians IQR | 1.09 (0.93, 1.51) | 1.56 (1.00, 2.77) | 2.82 (1.49, 4.72) | 0.085 | < 0.001 | 0.004 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.47 ± 0.91 | 4.65 ± 0.86 | 5.05 ± 0.97 | 1.000 | 0.047 | 0.281 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.75 ± 0.59 | 2.60 ± 0.78 | 2.87 ± 0.69 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.415 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L), medians IQR | 1.26 (1.13, 1.52) | 0.97 (0.85, 1.16) | 0.89 (0.79, 1.07) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.575 |

| Creatine (μmol/L) | 58.93 ± 10.45 | 55.24 ± 13.44 | 57.95 ± 13.09 | 0.767 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| UA (μmol/L), medians IQR | 302.50 (263.00, 351.00) | 288.50 (257.00, 325.00) | 466.50 (422.00, 513.00) | 0.543 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

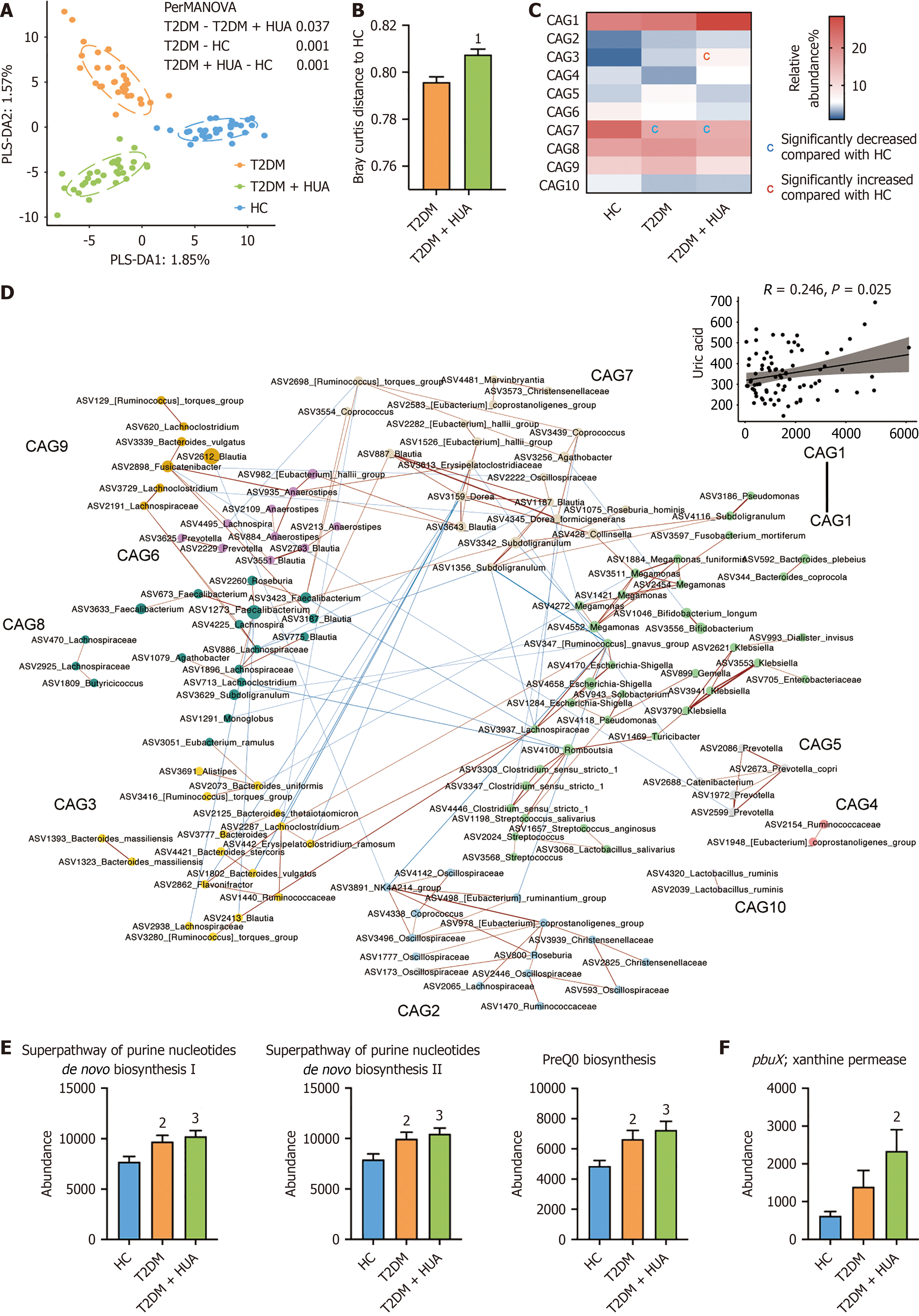

No differences in the richness (observed ASVs), evenness (Pielou index) and diversity (Shanon index) were found among the healthy subjects group; T2DM group; T2DM and HUA group (Supplementary Figure 1). The PCoA and score plots of PLS-DA suggested that composition of the gut microbiota differed significantly among the three groups (Figure 1A and B, Supplementary Figure 2). And we identified 322 ASVs and constructed ten CAGs based on sparse correlation analysis (Figure 1). The abundance of CAG3 (i.e., genus Bacteroides) was significantly higher in patients with T2DM and HUA group; whereas the abundance of CAG7 (i.e., family Lachnospiraceae) was significantly lower the group of T2DM patients with or without HUA group (Figure 1C). Additionally, serum uric acid was positively related to CAG1 (i.e., families Enterobacteriaceae and Bacteroidaceae) (Figure 1D). LEfSe analysis showed that the gut microbes in patients with T2DM and HUA significantly differed from those in the other two groups (Supplementary Figure 3). Patients with T2DM and HUA demonstrated a deficiency of uric acid-degrading bacteria such as Romboutsia, Blautia, and Clostridium sensu stricto 1 (Supplementary Figure 3). LEfSe analysis was used to further explore microbial function and identify differentially abundant KEGG pathways and genes among three groups. Notably, purine-related metabolic pathways and genes were significantly more abundant in patients with T2DM and HUA group (Figure 1E and F).

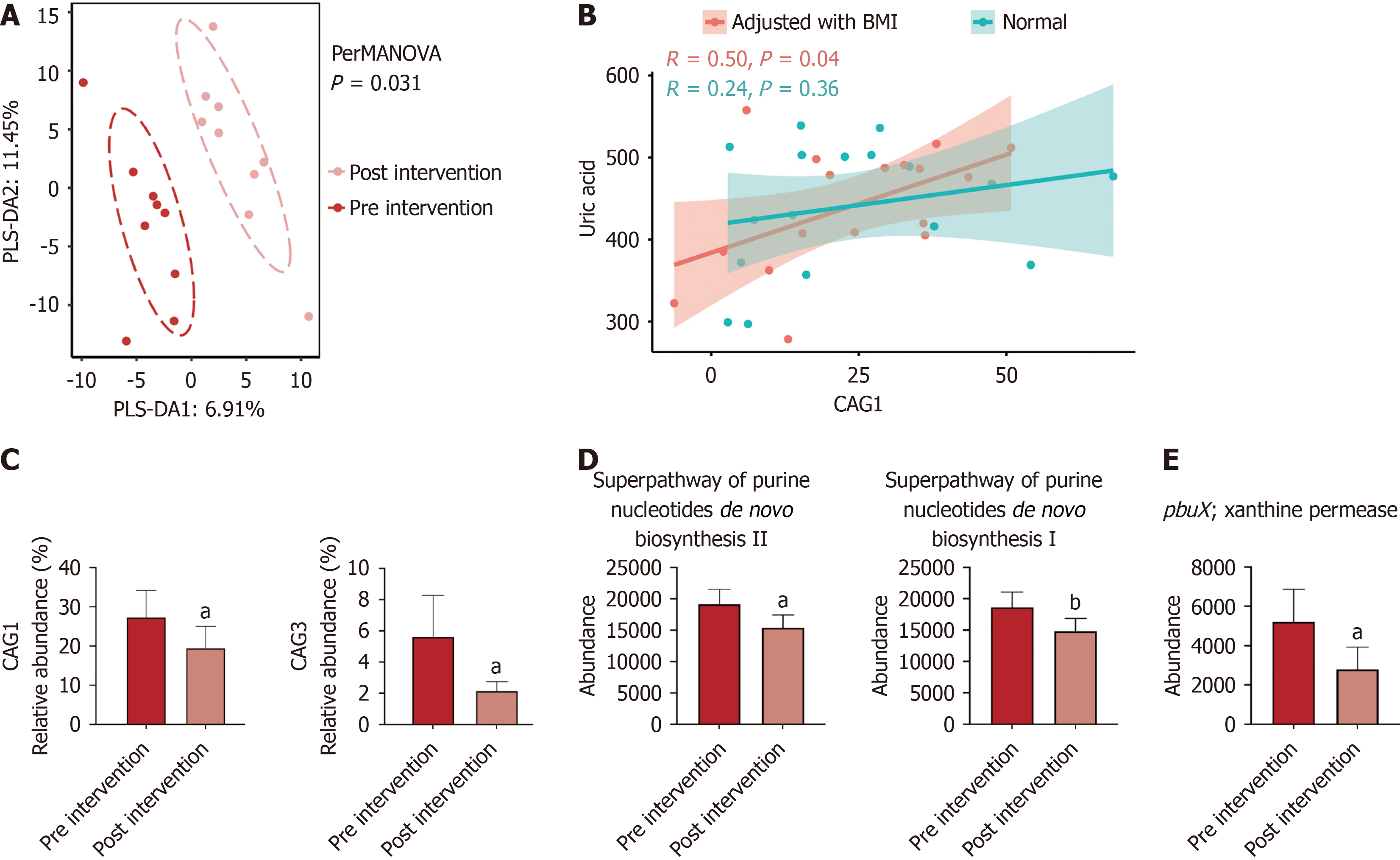

Clinical characteristics and biochemical parameters of individuals with treatment-naive T2DM and HUA before and after empagliflozin treatment are shown in Table 2. After three months’ treatment of empagliflozin treatment, HbA1c and uric acid were significantly reduced (Table 2). No differences in the richness (observed ASVs), evenness (Pielou index), and diversity (Shanon index) were found between patients before and after empagliflozin treatment (Supplementary Figure 4). Based on the Bray-Curtis distances, composition of gut microbiota after empagliflozin treatment differed significantly from that of before empagliflozin use (Figure 2A). Moreover, uric acid related to CAG1 and CAG3, which were elevated in patients in the T2DM and HUA group decreased after three months’ of empagliflozin treatment (Figure 2B). After adjusting for BMI, CAG1 was significantly associated with uric acid (Figure 2C). Empagliflozin treatment increased number of species from (Ruminococcus gauvreauii) group (Supplementary Figure 5). After empagliflozin treatment, the participants showed a significantly lower relative abundance of purine related metabolic pathways and genes than that observed before empagliflozin treatment (Figure 2D and E).

| Pre-empagliflozin (n = 9) | Post-empagliflozin (n = 9) | P value | |

| Age (year), medians IQR | 38.00 (34.00, 46.00) | ||

| Male, n (%) | 8 (88.9) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.47 ± 3.34 | 28.14 ± 3.52 | 0.051 |

| WHR | 0.98 ± 0.04 | 0.96 ± 0.03 | 0.140 |

| SBP (mmHg), medians IQR | 122.00 (120.00, 124.00) | 120.00 (119.00, 126.00) | 0.171 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 77.67 ± 6.40 | 74.33 ± 7.45 | 0.224 |

| FPG (mmol/L) | 7.34 ± 1.44 | 7.13 ± 1.17 | 0.607 |

| HbA1c (%), medians IQR | 8.40 (7.90, 8.90) | 6.60 (6.40, 6.90) | 0.008 |

| TG (mmol/L), medians IQR | 2.81 (1.89, 3.20) | 1.86 (1.62, 2.97) | 0.051 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 5.21 ± 1.08 | 5.20 ± 0.97 | 0.981 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.82 ± 0.89 | 3.17 ± 0.76 | 0.231 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L), medians IQR | 0.87 (0.83, 1.18) | 1.08 (0.87, 1.15) | 0.342 |

| Creatine (μmol/L) | 62.56 ± 14.98 | 57.63 ± 10.23 | 0.271 |

| UA (μmol/L), medians IQR | 503.00 (477.00, 513.00) | 370.50 (328.00, 423.00) | 0.012 |

In this study, we found that gut microbiota differed significantly between patients with T2DM and HUA and those of healthy subjects and patients with T2DM alone. In patients with T2DM and HUA, empagliflozin not only ameliorated glycemic metabolism, but also yielded significant uric acid reduction. Additionally, empagliflozin treatment may have partially restored gut microbiota involving purine metabolism in patients with T2DM and HUA.

Human uricase is a pseudogene, which has been inactivated early in hominid evolution[9]. Almost 1/3 of uric acid was excreted into the intestinal tract and metabolized by the gut microbiota, such as Clostridium, Anaerostipes, and Blautia[4,9]. The Clostridiaceae family has been reported to be able to use purines such as uric acid as sole carbon, nitrogen, and energy sources[20]. Besides, Romboutsia lituseburensis maintains microbial butyrate production in the presence of uric acid in humans[21]. In this study, we found a reduced abundance of uric acid-degrading bacteria, such as species from Rom

In addition to ameliorating hyperglycemia, empagliflozin has potential cardiovascular and renal benefits. What’s more, lots of studies have suggested that empagliflozin induces a rapid and sustained reduction of serum uric acid levels and clinical events related to HUA[11,24]. Empagliflozin’s decreasing serum uric acid may be due to accentuating urinary acid excretion, which is related to activation of the tubular transporter urate transporter 1 and urinary excretion of glu

Studies on the mechanisms by which empagliflozin might influence the gut microbiome were limited. Previous study suggested that empagliflozin treatment could affect the composition of gut microbiota in T2DM: Increased short-chain fatty acid-producing bacteria, such as Eubacterium, Roseburia, and Faecalibacterium, and lowered the levels of damaging bacteria, such as Escherichia Shigella, Bilophila, and Hungatella in patients with T2DM[12]. Additionally, empagliflozin also increased the levels of plasma metabolites such as sphingomyelin, but reduced glycochenodeoxycholate, cis-aconitate, and uric acid levels[12]. In obesity-related glomerulopathy C57BL/6J mice, empagliflozin reduced abundances of Firmicutes and Desulfovibrio and increased abundance of Akkermansia, and disrupted lipid metabolism which was closely associated with gut microbiota alterations[28]. Thus, the potential mechanisms by which empagliflozin might influence the gut microbiome associated with altered composition of the gut bacterium and metabolites.

The strength of our study lies in the fact that it is the first study to evaluate the effect of empagliflozin on gut microbiota in patients with T2DM and HUA. However, this study had some limitations. First, as the study was primarily observational, causality could not be established. Second, the sample size of our cohort was relatively small, although we used a strict screening process for recruitment to avoid the potential confounders. Large-scale studies are required to validate these results. Third, we investigated the effects of empagliflozin on uric acid and gut microbiota; however, no control group was used in this interventional analysis. A well-controlled trial is required to clarify that the effect of empagliflozin on uric acid reduction is associated with altered gut microbiota. Finally, batch adjustment in sequencing data analysis may have attenuated the differences among groups in the case-control analysis.

In conclusion, our study emphasizes the association between HUA and gut microbiota dysbiosis. The gut microbiota play an important role in purine metabolism in humans. Empagliflozin may partly restore gut microbiota involved in purine metabolism in patients with T2DM and HUA, suggesting that gut microbiota may be a promising target for preventive intervention against HUA in the future.

| 1. | Wu D, Chen R, Li Q, Lai X, Sun L, Zhang Z, Wen S, Sun S, Cao F. Tea (Camellia sinensis) Ameliorates Hyperuricemia via Uric Acid Metabolic Pathways and Gut Microbiota. Nutrients. 2022;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chen-Xu M, Yokose C, Rai SK, Pillinger MH, Choi HK. Contemporary Prevalence of Gout and Hyperuricemia in the United States and Decadal Trends: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2007-2016. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:991-999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 649] [Article Influence: 108.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Piao W, Zhao L, Yang Y, Fang H, Ju L, Cai S, Yu D. The Prevalence of Hyperuricemia and Its Correlates among Adults in China: Results from CNHS 2015-2017. Nutrients. 2022;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wang J, Chen Y, Zhong H, Chen F, Regenstein J, Hu X, Cai L, Feng F. The gut microbiota as a target to control hyperuricemia pathogenesis: Potential mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2022;62:3979-3989. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 39.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Björkegren JLM, Lusis AJ. Atherosclerosis: Recent developments. Cell. 2022;185:1630-1645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 424] [Cited by in RCA: 602] [Article Influence: 200.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Fang Y, Zhang C, Shi H, Wei W, Shang J, Zheng R, Yu L, Wang P, Yang J, Deng X, Zhang Y, Tang S, Shi X, Liu Y, Yang H, Yuan Q, Zhai R, Yuan H. Characteristics of the Gut Microbiota and Metabolism in Patients With Latent Autoimmune Diabetes in Adults: A Case-Control Study. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:2738-2746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gurung M, Li Z, You H, Rodrigues R, Jump DB, Morgun A, Shulzhenko N. Role of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes pathophysiology. EBioMedicine. 2020;51:102590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 501] [Cited by in RCA: 1070] [Article Influence: 214.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kasahara K, Kerby RL, Zhang Q, Pradhan M, Mehrabian M, Lusis AJ, Bergström G, Bäckhed F, Rey FE. Gut bacterial metabolism contributes to host global purine homeostasis. Cell Host Microbe. 2023;31:1038-1053.e10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 43.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Liu Y, Jarman JB, Low YS, Augustijn HE, Huang S, Chen H, DeFeo ME, Sekiba K, Hou BH, Meng X, Weakley AM, Cabrera AV, Zhou Z, van Wezel G, Medema MH, Ganesan C, Pao AC, Gombar S, Dodd D. A widely distributed gene cluster compensates for uricase loss in hominids. Cell. 2023;186:3400-3413.e20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 27.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rieg T, Vallon V. Development of SGLT1 and SGLT2 inhibitors. Diabetologia. 2018;61:2079-2086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 234] [Article Influence: 33.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Doehner W, Anker SD, Butler J, Zannad F, Filippatos G, Ferreira JP, Salsali A, Kaempfer C, Brueckmann M, Pocock SJ, Januzzi JL, Packer M. Uric acid and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibition with empagliflozin in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: the EMPEROR-reduced trial. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:3435-3446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Deng X, Zhang C, Wang P, Wei W, Shi X, Wang P, Yang J, Wang L, Tang S, Fang Y, Liu Y, Chen Y, Zhang Y, Yuan Q, Shang J, Kan Q, Yang H, Man H, Wang D, Yuan H. Cardiovascular Benefits of Empagliflozin Are Associated With Gut Microbiota and Plasma Metabolites in Type 2 Diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107:1888-1896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med. 1998;15:539-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Klindworth A, Pruesse E, Schweer T, Peplies J, Quast C, Horn M, Glöckner FO. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4276] [Cited by in RCA: 5171] [Article Influence: 397.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bolyen E, Rideout JR, Dillon MR, Bokulich NA, Abnet CC, Al-Ghalith GA, Alexander H, Alm EJ, Arumugam M, Asnicar F, Bai Y, Bisanz JE, Bittinger K, Brejnrod A, Brislawn CJ, Brown CT, Callahan BJ, Caraballo-Rodríguez AM, Chase J, Cope EK, Da Silva R, Diener C, Dorrestein PC, Douglas GM, Durall DM, Duvallet C, Edwardson CF, Ernst M, Estaki M, Fouquier J, Gauglitz JM, Gibbons SM, Gibson DL, Gonzalez A, Gorlick K, Guo J, Hillmann B, Holmes S, Holste H, Huttenhower C, Huttley GA, Janssen S, Jarmusch AK, Jiang L, Kaehler BD, Kang KB, Keefe CR, Keim P, Kelley ST, Knights D, Koester I, Kosciolek T, Kreps J, Langille MGI, Lee J, Ley R, Liu YX, Loftfield E, Lozupone C, Maher M, Marotz C, Martin BD, McDonald D, McIver LJ, Melnik AV, Metcalf JL, Morgan SC, Morton JT, Naimey AT, Navas-Molina JA, Nothias LF, Orchanian SB, Pearson T, Peoples SL, Petras D, Preuss ML, Pruesse E, Rasmussen LB, Rivers A, Robeson MS 2nd, Rosenthal P, Segata N, Shaffer M, Shiffer A, Sinha R, Song SJ, Spear JR, Swafford AD, Thompson LR, Torres PJ, Trinh P, Tripathi A, Turnbaugh PJ, Ul-Hasan S, van der Hooft JJJ, Vargas F, Vázquez-Baeza Y, Vogtmann E, von Hippel M, Walters W, Wan Y, Wang M, Warren J, Weber KC, Williamson CHD, Willis AD, Xu ZZ, Zaneveld JR, Zhang Y, Zhu Q, Knight R, Caporaso JG. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37:852-857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12449] [Cited by in RCA: 11554] [Article Influence: 1925.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, Han AW, Johnson AJ, Holmes SP. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods. 2016;13:581-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18515] [Cited by in RCA: 17676] [Article Influence: 1964.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, Gerken J, Schweer T, Yarza P, Peplies J, Glöckner FO. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D590-D596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15104] [Cited by in RCA: 18110] [Article Influence: 1509.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Rohart F, Gautier B, Singh A, Lê Cao KA. mixOmics: An R package for 'omics feature selection and multiple data integration. PLoS Comput Biol. 2017;13:e1005752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2024] [Cited by in RCA: 2081] [Article Influence: 260.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Douglas GM, Maffei VJ, Zaneveld JR, Yurgel SN, Brown JR, Taylor CM, Huttenhower C, Langille MGI. PICRUSt2 for prediction of metagenome functions. Nat Biotechnol. 2020;38:685-688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3069] [Cited by in RCA: 3112] [Article Influence: 622.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hartwich K, Poehlein A, Daniel R. The purine-utilizing bacterium Clostridium acidurici 9a: a genome-guided metabolic reconsideration. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Million M, Armstrong N, Khelaifia S, Guilhot E, Richez M, Lagier JC, Dubourg G, Chabriere E, Raoult D. The Antioxidants Glutathione, Ascorbic Acid and Uric Acid Maintain Butyrate Production by Human Gut Clostridia in The Presence of Oxygen In Vitro. Sci Rep. 2020;10:7705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zhang W, Wang T, Guo R, Cui W, Yu W, Wang Z, Jiang Y, Jiang M, Wang X, Liu C, Xiao J, Shang J, Wen X, Zhao Z. Variation of Serum Uric Acid Is Associated With Gut Microbiota in Patients With Diabetes Mellitus. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:761757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lin S, Zhang T, Zhu L, Pang K, Lu S, Liao X, Ying S, Zhu L, Xu X, Wu J, Wang X. Characteristic dysbiosis in gout and the impact of a uric acid-lowering treatment, febuxostat on the gut microbiota. J Genet Genomics. 2021;48:781-791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | You Y, Zhao Y, Chen M, Pan Y, Luo Z. Effects of empagliflozin on serum uric acid level of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2023;15:202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Suijk DLS, van Baar MJB, van Bommel EJM, Iqbal Z, Krebber MM, Vallon V, Touw D, Hoorn EJ, Nieuwdorp M, Kramer MMH, Joles JA, Bjornstad P, van Raalte DH. SGLT2 Inhibition and Uric Acid Excretion in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Normal Kidney Function. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022;17:663-671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Jin Y, Han C, Yang D, Gao S. Association between gut microbiota and diabetic nephropathy: a mendelian randomization study. Front Microbiol. 2024;15:1309871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | He G, Chen J, Hao W, Hu W. Causal effect of gut microbiota and diabetic nephropathy: a Mendelian randomization study. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2024;16:89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Lei L, Zhu T, Cui TJ, Liu Y, Hocher JG, Chen X, Zhang XM, Cai KW, Deng ZY, Wang XH, Tang C, Lin L, Reichetzeder C, Zheng ZH, Hocher B, Lu YP. Renoprotective effects of empagliflozin in high-fat diet-induced obesity-related glomerulopathy by regulation of gut-kidney axis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2024;327:C994-C1011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |