Published online Apr 15, 2025. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v16.i4.101994

Revised: January 4, 2025

Accepted: February 10, 2025

Published online: April 15, 2025

Processing time: 139 Days and 21.3 Hours

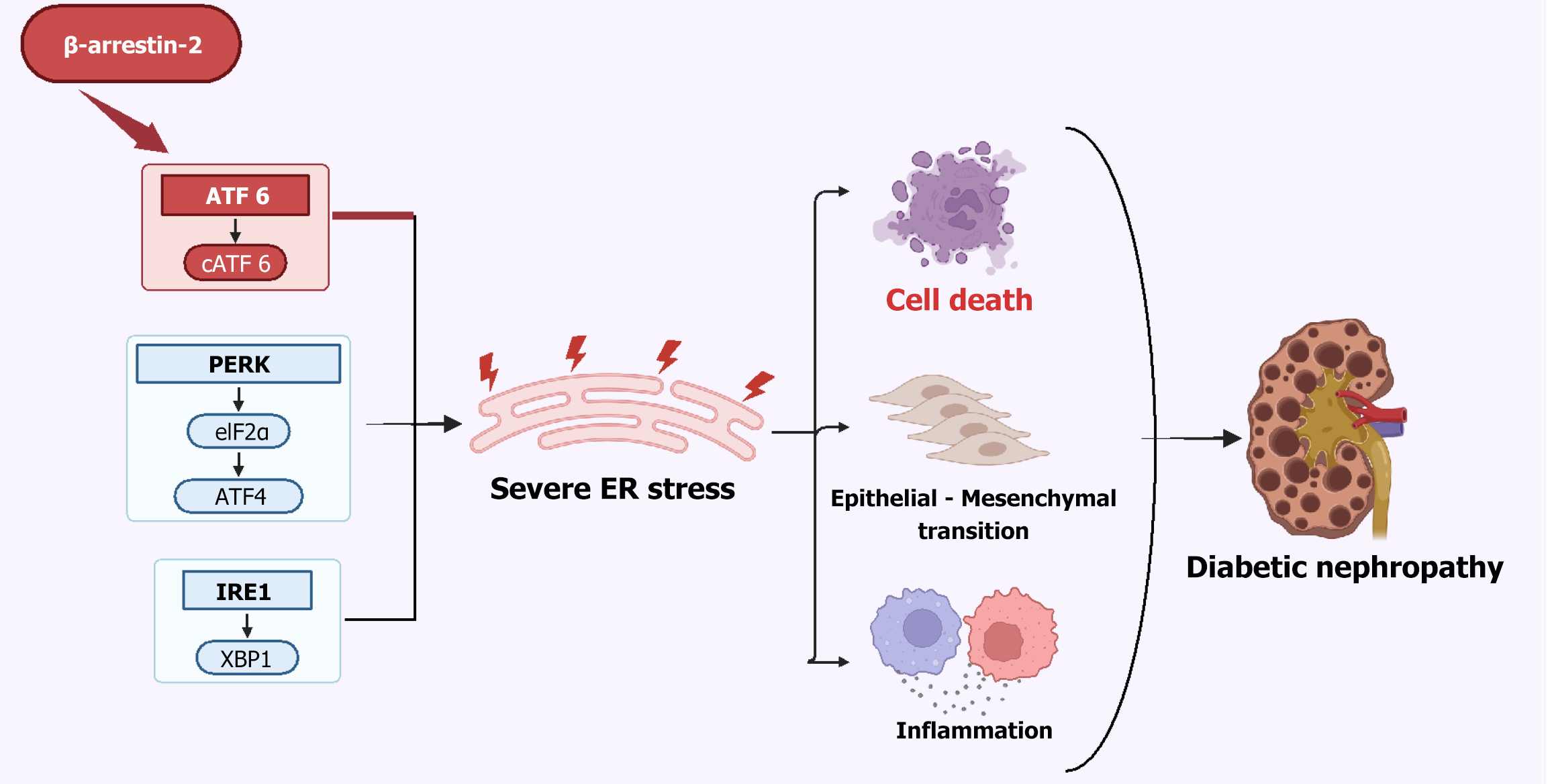

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is a well-known microvascular complication in patients with diabetes mellitus, which is characterized by the accumulation of extracellular matrix in the glomerular and tubulointerstitial compartments, along with the hyalinization of intrarenal vasculature. DN has recently emerged as a leading cause of chronic and end-stage renal disease. While the pathobiology of other diabetic microvascular complications, such as retinopathy, is largely understood and has reasonable therapeutic options, the mechanisms and management strategies for DN remain incompletely elucidated. In this editorial, we comment on the article by Liu et al, focusing on the mechanisms underlying the detrimental impact of β-arrestin-2 on the kidneys in the context of DN. The authors suggest that inhibiting β-arrestin-2 could alleviate renal damage through suppressing apoptosis of glomerular endothelial cells (GENCs), highlighting β-arrestin-2 as a promising therapeutic target for DN. The study proposed that β-arrestin-2 triggers endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress via the ATF6 signaling pathway, thereby promoting GENC apoptosis and exacerbating DN progression. Given the novel and crucial role of β-arrestin-2 in ER stress-related DN, it is imperative to further explore β-arrestin-2, its roles in ER stress and the potential therapeutic implications in DN.

Core Tip: Diabetic nephropathy (DN), a complication of diabetes mellitus, poses significant challenges in the management. Liu et al observed that β-arrestin-2 deteriorates DN through inducing endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, and inhibiting β-arrestin-2 may protect glomerular endothelial cells and mitigate DN progression by curbing ER stress. This research underscores the significance of ER stress in DN and reveals an innovative molecular pathway involving β-arrestin-2 that may contribute to DN progression, offering potential targets for therapeutic interventions. Nevertheless, further clinical validation and investigation are necessary to confirm the clinical application of these findings.

- Citation: Liu N, Yan WT, Xiong K. Exploring a novel mechanism for targeting β-arrestin-2 in the management of diabetic nephropathy. World J Diabetes 2025; 16(4): 101994

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v16/i4/101994.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v16.i4.101994

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a group of metabolic diseases characterized by hyperglycemia, leading to a substantial negative impact on the morbidity and mortality with its associated devastating complications, such as diabetic cardiomyopathy, neuropathy, nephropathy, and retinopathy[1,2]. Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is one of the most prevalent and serious microvascular complications, and has recently become a leading cause of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease, imposing significant individual and socioeconomic costs. Mechanistically, the pathogenesis of DN involves a multifaceted network of molecular mechanisms, including hyperglycemia, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, inflammatory responses, accumulation of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) as well as activation of the transforming growth factor-β signaling pathway[3-5]. Current treatment for DN focuses on maintaining strict glycemic control, stabilizing blood pressure and preserving renal function[6]. Although these conventional approaches have been proven effective in slowing down DN progression, they are unable to completely halt or reverse this disease, contributing to a large risk of progression[7]. Exploring the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the onset of DN, and identifying novel therapeutic strategies and drug candidates to inhibit its progression are pressing challenges, as well as crucial issues with significant implications in global social and economic development.

The ER is an intracellular organelle responsible for protein synthesis, folding, and structural maturation, and maintaining protein homeostasis through protein quality control system[8]. However, various genetic and environmental factors, such as hyperglycemia, oxidative stress and lipotoxicity, have the potential to disrupt cellular homeostasis, leading to the accumulation of misfolded proteins and initiation of ER stress[9]. Subsequently, an adaptive unfolded protein response (UPR), which is a complex signaling network consisting of three primary pathways: PERK/eIF2α/ATF4, IRE1/XBP1, and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), is triggered to restore proteostasis and ensure cells survival[10]. Nevertheless, abnormal ER stress and maladaptive UPR signaling often result in cell death and dysfunction, thereby contributing to the onset and progression of various diseases, such as metabolic disorders, neurodegeneration, autoimmunity and DN[11]. Over the past few decades, accumulating evidence has revealed that ER stress is obviously activated during progression of DN, and is increasingly recognized as a critical contributor to DN pathogenesis[12]. Previous studies have demonstrated that AGEs and high glucose can induce DN in mice by provoking ER stress, ultimately leading to kidney cell death through activation of three classic UPR pathways[13]. For instance, reticulon-1A (RTN1A), a potentially key regulator of ER stress, contributes to DN via inducing cell death in podocytes and kidney tubular epithelial cells[14,15]. ER stress is also closely linked to oxidative stress and inflammatory responses. Disruption of Ca2+ homeostasis and increased reactive oxygen species exacerbate oxidative stress, resulting in renal injury. Activation of UPR pathways can further promote the release of proinflammatory factors, such as interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-6, through nuclear factor (NF)-κB signaling and NLRP3-related inflammation, leading to an inflammatory response and contributing to the onset and progression of DN[16-18]. Additionally, ER stress has been reported to influence epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in renal tubular epithelial cells; a pivotal pathological characteristic of DN that results in deterioration of renal function and tubulointerstitial fibrosis during DN progression[19]. For example, ER stress can induce EMT progression via activation of the XBP1/Hrd1/Nrf2 pathway in DN[20]. Given the pivotal role of ER stress in the progression of DN, targeting ER stress, especially UPR pathways, has emerged as a potential therapeutic strategy[21,22]. Further understanding of ER stress and its underlying mechanisms in DN pathophysiology might pave the way for new therapeutic approaches.

Arrestins are a protein family consisting of four members, with arrestin-1 and -4 being confined to expression in specific ocular cells, whereas arrestin-2 and -3 exhibit widespread distribution throughout the cytoplasm of various cell types. Arrestin-1 and -2 are also known as β-arrestin-1 and β-arrestin-2, respectively[23], and play pivotal roles in the desensitization and intracellular signaling of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). β-Arrestins also serve as scaffold proteins, facilitating interactions of a variety of signaling molecules to modulate diverse signaling pathways and impact a wide range of biological processes under physiological and pathophysiological conditions[24-26]. Recent studies have demonstrated that β-arrestins are implicated in DN progression by engaging in various pathological processes, including aberrant ER stress, inflammation as well as renal cell death[27-29]. It is reported that the expression of β-arrestins is positively correlated with the severity of DN, and they can inhibit podocyte autophagy via reducing ATG12–ATG5 conjugation, thus exacerbating renal injury[27,30]. In addition, β-arrestins have been shown to aggravate DN progression via promoting podocyte apoptosis through activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway[28]. However, it is important to note that β-arrestin-1 and -2 may perform distinct functions in DN under specific pathological condition due to the existence of biased signaling transduction[31]. Another study has revealed that β-arrestin-2 may mitigate diabetic renal fibrosis by suppressing the NF-κB-mediated inflammatory pathway, thereby decelerating the development of DN[32]. The involvement of β-arrestins in DN makes them an attractive target for therapeutic intervention. Further research is needed to fully elucidate the underlying mechanisms of action of β-arrestins in DN and translate these findings into clinical therapies.

Although emerging evidence suggests that β-arrestin-2 plays an important role in the progression of DN, the underlying mechanisms are still not completely elucidated. Increasing data implicates β-arrestin-2 in the modulation of UPR pathways and regulation of ER stress[33]. Nevertheless, its involvement in DN through the regulation of ER stress has not been reported before. The study[34] demonstrated that β-arrestin-2 induced ER stress via upregulating associated molecules ER chaperone (BiP) and DNA damage-inducible transcript 3 protein (CHOP) in glomerular endothelial cells (GENCs). The authors then revealed that β-arrestin-2 promoted the nuclear translocation of ATF6, a pivotal regulator in the UPR, under high glucose stimulation, thereby enhancing BiP and CHOP expression, amplifying ER stress, inducing GENCs apoptosis and accelerating progression of DN. The authors provided evidence supporting the therapeutic efficiency of silencing β-arrestin-2 in DN murine models by applying adeno-associated virus (AAV) containing shRNA specific to β-arrestin-2 (Figure 1). These findings not only provide an innovative mechanistic insight for DN pathogenesis, but also highlight β-arrestin-2 as a promising therapeutic target for DN[34]. Considering that current DN therapies focus on glycemic control, as well as anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effects, β-arrestin-2 inhibition represents a more specific and precise therapeutic intervention due to its ability to suppress ER stress and apoptosis in GENCs via modulating ATF6 – a previously untargeted pathway (Table 1)[35-50]. In addition, combining β-arrestin-2 inhibition with anti-inflammatory or antioxidant therapies may yield broader therapeutic effects by simultaneously inhibiting both oxidative stress and ER stress, thus providing a more comprehensive and effective strategy for managing DN.

| Category of DN therapies | Therapeutic targets | Mechanism of action | Ref. |

| Established therapies | RAS blockers (ACEi/ARBs) | Suppress renal inflammation, reduce angiotensin II-mediated vasoconstriction, and alleviate glomerular hypertension | [35,36] |

| SGLT2 inhibitors | Increase urinary sugar excretion, reduce hyperglycemia and glomerular hyperfiltration by inhibiting sodium-glucose co-transport | [37] | |

| GLP-1 agonists | Lower hyperglycemia by promoting insulin secretion and inhibiting glucagon secretion | [38,39] | |

| MRAs | Inhibit oxidative stress, inflammation and fibrosis via blocking MR overactivation | [40] | |

| Endothelin antagonists | Improve renal microcirculation and reduce proteinuria by alleviating inflammation, fibrosis and podocyte injury | [41,42] | |

| DPP-4 inhibitors | Improve glycaemic control, reduce kidney damage, proteinuria and vascular inflammation through blocking GLP-1 degradation | [43] | |

| Emerging therapies | Phosphodiesterase inhibitors | Reduce proteinuria, inflammation and fibrosis | [44] |

| VDR agonists | Ameliorate the damage to proximal tubular epithelial cells, reduce fibrosis and proteinuria | [45,46] | |

| Selective PPAR agonists (PPAR-γ/PPAR-α/δ) | Regulate metabolism, reduce hyperglycemia, proteinuria, inflammation and fibrosis | [47,48] | |

| TGF-β inhibitors | Prevent fibrosis and extracellular matrix accumulation | [49,50] | |

| β-arrestin-2 inhibitors | Inhibit ER stress-induced renal injury, alleviate inflammation and fibrosis | [28,34] |

While the experimental data of this study are compelling, numerous questions need to be addressed before β-arrestin-2 can be considered a viable therapeutic target and translated into clinical practice. For example, there is currently no inhibitor specifically targeting β-arrestin-2, and challenges persist in ensuring that such inhibitors selectively target renal tissues. Targeted therapies utilizing CRISPR, RNA interference or AAV incorporating shRNA technology, along with nanoparticle-based approaches may provide solutions for the specific inhibition of β-arrestin-2 while enhancing renal tissue specificity. Further investigation using rodent DN models (such as db/db mice and streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats), as well as larger animal models (such as pigs and canines) is necessary to verify whether inhibiting β-arrestin-2 can yield significant therapeutic benefits in human patients with DN while minimizing adverse effects. The specificity, safety, potential adverse effects and long-term efficacy of targeting β-arrestin-2 warrant sustained and thorough evaluation, particularly considering the complex and multifaceted roles that β-arrestin-2 and ER stress play in multiple physiological and pathological processes. Additionally, the mechanism by which β-arrestin-2 enhances the translocation of ATF6 remains unclear. A recent study reported that β-arrestin-2 may interact with GRP78 to modulate the GRP78/ATF6/CHOP apoptosis signaling pathway, ultimately contributing to the pathogenesis of primary Sjogren’s syndrome[51]. Whether β-arrestin-2 upregulates ATF6 via direct interaction with chaperone proteins, such as GRP78, or via other upstream modulatory mechanisms remains an open question. These could be verified through various experimental approaches, such as co-immunoprecipitation and molecular docking studies. Further investigation into these potential mechanisms and in-depth understanding of the crosstalk between β-arrestin-2 and ER stress may unveil new avenues for therapeutic interventions in DN. Further exploration on β-arrestin-2 in conjunction with other therapy approaches is warranted to enhance therapeutic efficacy for diabetic patients with DN.

DN remains one of the most common and devastating complications of DM, imposing a substantial health burden worldwide. ER stress, governed by a complex network of molecules and signaling pathways, plays vital roles in the pathogenesis and progression of DN. Inhibition of β-arrestin-2 has shown significant therapeutic potential by modulating ATF6, thereby attenuating ER stress, protecting GENCs from apoptosis and decelerating DN progression. These findings imply that β-arrestin-2 emerges as a promising novel therapeutic target for DN clinical treatment. Translating these findings from bench to bedside could initiate a new era of targeted therapies for DN, highlighting the urgent need for further investigation into β-arrestin-2 inhibitors or modulators, with particular focus on tissue specificity and therapeutic safety.

We would like to express our sincere appreciation to Xin-Xing Wan and Zu-Jian Xiong for his expert advice and guidance on this manuscript.

| 1. | Wan XX, Zhang DY, Khan MA, Zheng SY, Hu XM, Zhang Q, Yang RH, Xiong K. Stem Cell Transplantation in the Treatment of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: From Insulin Replacement to Beta-Cell Replacement. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:859638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zheng SY, Wan XX, Kambey PA, Luo Y, Hu XM, Liu YF, Shan JQ, Chen YW, Xiong K. Therapeutic role of growth factors in treating diabetic wound. World J Diabetes. 2023;14:364-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 3. | Hu Q, Jiang L, Yan Q, Zeng J, Ma X, Zhao Y. A natural products solution to diabetic nephropathy therapy. Pharmacol Ther. 2023;241:108314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 30.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jin Q, Liu T, Qiao Y, Liu D, Yang L, Mao H, Ma F, Wang Y, Peng L, Zhan Y. Oxidative stress and inflammation in diabetic nephropathy: role of polyphenols. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1185317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gupta S, Dominguez M, Golestaneh L. Diabetic Kidney Disease: An Update. Med Clin North Am. 2023;107:689-705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Psyllaki A, Tziomalos K. New perspectives in the management of diabetic nephropathy. World J Diabetes. 2024;15:1086-1090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Alicic RZ, Rooney MT, Tuttle KR. Diabetic Kidney Disease: Challenges, Progress, and Possibilities. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12:2032-2045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1257] [Cited by in RCA: 1784] [Article Influence: 223.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ajoolabady A, Kaplowitz N, Lebeaupin C, Kroemer G, Kaufman RJ, Malhi H, Ren J. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in liver diseases. Hepatology. 2023;77:619-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 91.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chen X, Shi C, He M, Xiong S, Xia X. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: molecular mechanism and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 344] [Article Influence: 172.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chen X, Cubillos-Ruiz JR. Endoplasmic reticulum stress signals in the tumour and its microenvironment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2021;21:71-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 253] [Cited by in RCA: 795] [Article Influence: 198.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hetz C, Zhang K, Kaufman RJ. Mechanisms, regulation and functions of the unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2020;21:421-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 499] [Cited by in RCA: 1598] [Article Influence: 319.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lindenmeyer MT, Rastaldi MP, Ikehata M, Neusser MA, Kretzler M, Cohen CD, Schlöndorff D. Proteinuria and hyperglycemia induce endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:2225-2236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cao Y, Hao Y, Li H, Liu Q, Gao F, Liu W, Duan H. Role of endoplasmic reticulum stress in apoptosis of differentiated mouse podocytes induced by high glucose. Int J Mol Med. 2014;33:809-816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fan Y, Zhang J, Xiao W, Lee K, Li Z, Wen J, He L, Gui D, Xue R, Jian G, Sheng X, He JC, Wang N. Rtn1a-Mediated Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Podocyte Injury and Diabetic Nephropathy. Sci Rep. 2017;7:323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Xie Y, E J, Cai H, Zhong F, Xiao W, Gordon RE, Wang L, Zheng YL, Zhang A, Lee K, He JC. Reticulon-1A mediates diabetic kidney disease progression through endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondrial contacts in tubular epithelial cells. Kidney Int. 2022;102:293-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zhang X, Huo Z, Jia X, Xiong Y, Li B, Zhang L, Li X, Li X, Fang Y, Dong X, Chen G. (+)-Catechin ameliorates diabetic nephropathy injury by inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum stress-related NLRP3-mediated inflammation. Food Funct. 2024;15:5450-5465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zhang K, Kaufman RJ. From endoplasmic-reticulum stress to the inflammatory response. Nature. 2008;454:455-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1641] [Cited by in RCA: 1584] [Article Influence: 93.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Li Q, Zhang K, Hou L, Liao J, Zhang H, Han Q, Guo J, Li Y, Hu L, Pan J, Yu W, Tang Z. Endoplasmic reticulum stress contributes to pyroptosis through NF-κB/NLRP3 pathway in diabetic nephropathy. Life Sci. 2023;322:121656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Loeffler I, Wolf G. Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Diabetic Nephropathy: Fact or Fiction? Cells. 2015;4:631-652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 20.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Liu Z, Nan P, Gong Y, Tian L, Zheng Y, Wu Z. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-triggered ferroptosis via the XBP1-Hrd1-Nrf2 pathway induces EMT progression in diabetic nephropathy. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;164:114897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Luo ZF, Feng B, Mu J, Qi W, Zeng W, Guo YH, Pang Q, Ye ZL, Liu L, Yuan FH. Effects of 4-phenylbutyric acid on the process and development of diabetic nephropathy induced in rats by streptozotocin: regulation of endoplasmic reticulum stress-oxidative activation. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2010;246:49-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zhang MZ, Wang Y, Paueksakon P, Harris RC. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibition slows progression of diabetic nephropathy in association with a decrease in endoplasmic reticulum stress and an increase in autophagy. Diabetes. 2014;63:2063-2072. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Peterson YK, Luttrell LM. The Diverse Roles of Arrestin Scaffolds in G Protein-Coupled Receptor Signaling. Pharmacol Rev. 2017;69:256-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 353] [Cited by in RCA: 329] [Article Influence: 41.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | DeFea KA. Beta-arrestins as regulators of signal termination and transduction: how do they determine what to scaffold? Cell Signal. 2011;23:621-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wess J, Oteng AB, Rivera-Gonzalez O, Gurevich EV, Gurevich VV. β-Arrestins: Structure, Function, Physiology, and Pharmacological Perspectives. Pharmacol Rev. 2023;75:854-884. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 29.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Pydi SP, Barella LF, Zhu L, Meister J, Rossi M, Wess J. β-Arrestins as Important Regulators of Glucose and Energy Homeostasis. Annu Rev Physiol. 2022;84:17-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Liu J, Li QX, Wang XJ, Zhang C, Duan YQ, Wang ZY, Zhang Y, Yu X, Li NJ, Sun JP, Yi F. β-Arrestins promote podocyte injury by inhibition of autophagy in diabetic nephropathy. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:e2183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Wang Y, Li H, Song SP. β-Arrestin 1/2 Aggravates Podocyte Apoptosis of Diabetic Nephropathy via Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:1724-1732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Zhan H, Jin J, Liang S, Zhao L, Gong J, He Q. Tripterygium glycoside protects diabetic kidney disease mouse serum-induced podocyte injury by upregulating autophagy and downregulating β-arrestin-1. Histol Histopathol. 2019;34:943-952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Tang LQ, Ni WJ, Cai M, Ding HH, Liu S, Zhang ST. Renoprotective effects of berberine and its potential effect on the expression of β-arrestins and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 in streptozocin-diabetic nephropathy rats. J Diabetes. 2016;8:693-700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Cahill TJ 3rd, Thomsen AR, Tarrasch JT, Plouffe B, Nguyen AH, Yang F, Huang LY, Kahsai AW, Bassoni DL, Gavino BJ, Lamerdin JE, Triest S, Shukla AK, Berger B, Little J 4th, Antar A, Blanc A, Qu CX, Chen X, Kawakami K, Inoue A, Aoki J, Steyaert J, Sun JP, Bouvier M, Skiniotis G, Lefkowitz RJ. Distinct conformations of GPCR-β-arrestin complexes mediate desensitization, signaling, and endocytosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:2562-2567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 277] [Article Influence: 34.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Wang S, Yang Z, Xiong F, Chen C, Chao X, Huang J, Huang H. Betulinic acid ameliorates experimental diabetic-induced renal inflammation and fibrosis via inhibiting the activation of NF-κB signaling pathway. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2016;434:135-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Feng M, Wang R, Deng L, Yang Y, Xia S, Liu F, Luo L. Arrestin beta-2 deficiency exacerbates periodontal inflammation by mediating activating transcription factor 6 activation and abnormal remodelling of the extracellular matrix. J Clin Periodontol. 2024;51:742-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Liu J, Song XY, Li XT, Yang M, Wang F, Han Y, Jiang Y, Lei YX, Jiang M, Zhang W, Tang DQ. β-Arrestin-2 enhances endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced glomerular endothelial cell injury by activating transcription factor 6 in diabetic nephropathy. World J Diabetes. 2024;15:2322-2337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Bain RP, Rohde RD. The effect of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition on diabetic nephropathy. The Collaborative Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1456-1462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3760] [Cited by in RCA: 3555] [Article Influence: 111.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 36. | Bell DSH, Jerkins T. The potential for improved outcomes in the prevention and therapy of diabetic kidney disease through 'stacking' of drugs from different classes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2024;26:2046-2053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, Bompoint S, Heerspink HJL, Charytan DM, Edwards R, Agarwal R, Bakris G, Bull S, Cannon CP, Capuano G, Chu PL, de Zeeuw D, Greene T, Levin A, Pollock C, Wheeler DC, Yavin Y, Zhang H, Zinman B, Meininger G, Brenner BM, Mahaffey KW; CREDENCE Trial Investigators. Canagliflozin and Renal Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes and Nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2295-2306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2826] [Cited by in RCA: 3967] [Article Influence: 661.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Yao H, Zhang A, Li D, Wu Y, Wang CZ, Wan JY, Yuan CS. Comparative effectiveness of GLP-1 receptor agonists on glycaemic control, body weight, and lipid profile for type 2 diabetes: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2024;384:e076410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Reference Citation Analysis (12)] |

| 39. | Sattar N, Lee MMY, Kristensen SL, Branch KRH, Del Prato S, Khurmi NS, Lam CSP, Lopes RD, McMurray JJV, Pratley RE, Rosenstock J, Gerstein HC. Cardiovascular, mortality, and kidney outcomes with GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;9:653-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 844] [Article Influence: 211.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Bakris GL, Agarwal R, Anker SD, Pitt B, Ruilope LM, Rossing P, Kolkhof P, Nowack C, Schloemer P, Joseph A, Filippatos G; FIDELIO-DKD Investigators. Effect of Finerenone on Chronic Kidney Disease Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2219-2229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1696] [Cited by in RCA: 1495] [Article Influence: 299.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 41. | Koomen JV, Stevens J, Bakris G, Correa-Rotter R, Hou FF, Kitzman DW, Kohan DE, Makino H, McMurray JJV, Parving HH, Perkovic V, Tobe SW, de Zeeuw D, Heerspink HJL. Individual Atrasentan Exposure is Associated With Long-term Kidney and Heart Failure Outcomes in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes and Chronic Kidney Disease. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2021;109:1631-1638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Hu Q, Chen Y, Deng X, Li Y, Ma X, Zeng J, Zhao Y. Diabetic nephropathy: Focusing on pathological signals, clinical treatment, and dietary regulation. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;159:114252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Kim YG, Byun J, Yoon D, Jeon JY, Han SJ, Kim DJ, Lee KW, Park RW, Kim HJ. Renal Protective Effect of DPP-4 Inhibitors in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients: A Cohort Study. J Diabetes Res. 2016;2016:1423191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Navarro-González JF, Mora-Fernández C, Muros de Fuentes M, Chahin J, Méndez ML, Gallego E, Macía M, del Castillo N, Rivero A, Getino MA, García P, Jarque A, García J. Effect of pentoxifylline on renal function and urinary albumin excretion in patients with diabetic kidney disease: the PREDIAN trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:220-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Wang H, Yu X, Liu D, Qiao Y, Huo J, Pan S, Zhou L, Wang R, Feng Q, Liu Z. VDR Activation Attenuates Renal Tubular Epithelial Cell Ferroptosis by Regulating Nrf2/HO-1 Signaling Pathway in Diabetic Nephropathy. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024;11:e2305563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 33.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Chen H, Zhang H, Li AM, Liu YT, Liu Y, Zhang W, Yang C, Song N, Zhan M, Yang S. VDR regulates mitochondrial function as a protective mechanism against renal tubular cell injury in diabetic rats. Redox Biol. 2024;70:103062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Jia Z, Sun Y, Yang G, Zhang A, Huang S, Heiney KM, Zhang Y. New Insights into the PPAR γ Agonists for the Treatment of Diabetic Nephropathy. PPAR Res. 2014;2014:818530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Ke Q, Xiao Y, Liu D, Shi C, Shen R, Qin S, Jiang L, Yang J, Zhou Y. PPARα/δ dual agonist H11 alleviates diabetic kidney injury by improving the metabolic disorders of tubular epithelial cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2024;222:116076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Border WA, Noble NA. Evidence that TGF-beta should be a therapeutic target in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. 1998;54:1390-1391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Zhang XX, Liu Y, Xu SS, Yang R, Jiang CH, Zhu LP, Xu YY, Pan K, Zhang J, Yin ZQ. Asiatic acid from Cyclocarya paliurus regulates the autophagy-lysosome system via directly inhibiting TGF-β type I receptor and ameliorates diabetic nephropathy fibrosis. Food Funct. 2022;13:5536-5546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Huang L, Liu Q, Zhou T, Zhang J, Tian Q, Zhang Q, Wei W, Wu H. Deficiency of β-arrestin2 alleviates apoptosis through GRP78-ATF6-CHOP signaling pathway in primary Sjögren's syndrome. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;101:108281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |