Published online Apr 15, 2025. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v16.i4.101731

Revised: December 21, 2024

Accepted: January 14, 2025

Published online: April 15, 2025

Processing time: 156 Days and 17.8 Hours

Despite therapeutic benefits, discontinuation of tirzepatide is common in ran

To explore the reasons for permanent discontinuation of tirzepatide vs controls [placebo, insulin, and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1Ras)] in RCTs.

Relevant RCTs were systematically searched using related terms through multiple databases such as MEDLINE

Seventeen RCTs (n = 14645), mostly having low risks of bias, were analyzed. Compared to placebo, the risk of permanent discontinuation of the study drug was substantially lower with tirzepatide 10 mg (RR: 0.69, 95%CI: 0.51-0.93, P = 0.02) and similar with tirzepatide 5 mg (RR: 0.74, 95%CI: 0.47-1.17, P = 0.20) and 15 mg (RR: 0.94, 95%CI: 0.68-1.31, P = 0.71). Tirzepatide had identical discontinuation risks when compared to insulin at 5 mg (RR: 0.96, 95%CI: 0.75-1.24, P = 0.77) and 10 mg (RR: 1.19, 95%CI: 0.77-1.82, P = 0.44) doses, whereas such risk was higher with tirzepatide 15 mg than insulin (RR: 1.31, 95%CI: 1.03-1.67, P = 0.03). Compared to GLP-1RA, the permanent discontinuation risk was similar with tirzepatide 5 mg (RR: 0.98, 95%CI: 0.70-1.37, P = 0.90) but was higher with tirzepatide 10 mg (RR: 1.40, 95%CI: 1.03-1.90, P = 0.03) and 15 mg (RR: 1.70, 95%CI: 1.27-2.27, P = 0.0004). Tirzepatide, at all doses, had higher risks of AE-related discontinuation than insulin; such risks were only greater with higher doses of tirzepatide than with placebo or GLP-1RA. Discontinuation risk due to withdrawal by the study subjects was lower with tirzepatide than with placebo or insulin. Compared to the placebo, tirzepatide (all doses) conferred a lower risk of study drug discontinuation due to other causes not specifically mentioned.

The discontinuation risk is not higher in tirzepatide group than in the placebo arm. Many factors other than AEs led to drug discontinuation in the included RCTs.

Core Tip: The reasons for permanent discontinuation of tirzepatide vs controls [placebo, insulin, and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1Ras)] are not systematically assessed based on data from randomized controlled trials. We studied 17 randomized controlled trials (n = 14645) and found that the risks of study drug discontinuation were greater with higher doses of tirzepatide than with insulin or GLP-1RAs. Tirzepatide, at all doses, had higher risks of adverse event-related discontinuation than insulin. Such risks were only greater with higher doses of tirzepatide than with placebo or GLP-1RAs. Discontinuation risk due to withdrawal by the study subjects was lower with tirzepatide than with placebo or insulin.

- Citation: Kamrul-Hasan ABM, Pappachan JM, Dutta D, Nagendra L, Kuchay MS, Kapoor N. Reasons for discontinuing tirzepatide in randomized controlled trials: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Diabetes 2025; 16(4): 101731

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v16/i4/101731.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v16.i4.101731

Tirzepatide, a 39-amino-acid synthetic peptide recently developed for managing metabolic disorders in individuals with obesity, exhibits dual agonist activity at both the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptors, demonstrating a greater affinity for glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptors[1]. The United States Food and Drug Administration has approved tirzepatide once-weekly subcutaneous injection to improve glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes (T2D) and chronic weight management in the presence of obesity/overweight[2,3]. In multiple randomized controlled trials (RCTs), tirzepatide has been proven to be highly effective in reducing glycated haemoglobin in adults with T2D and robust reductions in body weight in those with obesity with/without T2D[4,5]. Tirzepatide has emerged as the most effective weight loss medication available for clinical use today.

Despite therapeutic benefits, its discontinuation due to adverse events (AEs), non-adherence, and other factors remains a critical concern[6]. Most RCTs of tirzepatide have reported the proportions of the study subjects who discontinued the study drugs and the reasons for discontinuation. However, no systematic review and meta-analysis (SRM) has been conducted specifically highlighting this issue. Considering the serious consequences of obesity and T2D, it is crucial to critically appraise the reasons for the discontinuation of an important drug molecule with outstanding therapeutic benefits in managing these conditions. Therefore, we conducted an SRM to explore the reasons for discontinuing tirzepatide across various clinical trials, providing a comprehensive understanding of its tolerability and identifying potential areas for intervention to improve patient adherence and outcomes.

This SRM complied with the guidelines outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklists[7,8]. The SRM was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42024566276), and the protocol summary is accessible online.

A systematic search was conducted through multiple databases and registers, such as MEDLINE (via PubMed), Scopus, Cochrane Central Register, and ClinicalTrials.gov. The search covered these sources from their inception until June 20, 2024. The search strategy utilized a Boolean approach with the terms “tirzepatide” or “LY3437943”. The search terms were applied to titles only. A thorough and careful search was conducted to find any recently published or unpublished clinical trials in English. The search also included examining references within the retrieved clinical trials included in this study and relevant journals.

The selection of clinical trials for this meta-analysis was based on the PICOS criteria for SRM. The patient population (P) consisted of individuals treated with tirzepatide for any clinical indication. The intervention (I) was the administration of tirzepatide. The control (C) included individuals receiving either a placebo or any other active comparator. The outcomes (O) included the proportions of study subjects with permanent discontinuation of the study drug. The study (S) included only the RCTs. This analysis included RCTs with a minimum 12-week duration with study subjects aged ≥ 18 years. The trials had at least two treatment arms/groups, with one receiving tirzepatide as monotherapy or as an add-on to other drugs and the other receiving a placebo or any other active comparator either alone or as an add-on to other drugs. Clinical trials involving animals or healthy humans, nonrandomized trials, RCTs < 12 weeks in duration, retrospective studies, pooled analyses of clinical trials, conference proceedings, letters to editors, case reports, and articles lacking data with outcomes of interest were excluded.

The primary outcome was the proportions of study subjects with permanent discontinuation of the study drug in the tirzepatide vs the control group(s). Secondary outcomes were the reasons behind such discontinuation. The analyses were stratified according to the type of control groups and the dose of tirzepatide.

Data extraction was independently conducted by four review authors using standardized data extraction forms, with details provided elsewhere[9]. The handling of missing data has also been elaborated upon in the same source[9]. Four authors independently performed the risk of bias (RoB) assessment using version 2 of the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) in the RevMan computer program, version 7.2.0[10,11]. Specific biases have been outlined in the same source[9]. Publication bias, when appropriate (at least ten studies in a forest plot), was evaluated using funnel plots in the same software[11-13].

For dichotomous variables, the results of the outcomes were expressed as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Forest plots were created using the RevMan computer program, version 7.2.0., which portrayed the comparison of RR for primary and secondary outcomes, with the left side favoring tirzepatide and the right side favoring the control group(s)[11]. Random effects analysis models were chosen for the review to account for the expected heterogeneity arising from differences in population characteristics and research durations. The inverse variance statistical method was applied for all instances. The results included forest plots incorporating data from at least two RCTs. A significance level of P < 0.05 was used.

The evaluation of heterogeneity was initially performed by analyzing forest plots. Afterward, a χ2-test was conducted with N-1 degrees of freedom and a significance level of 0.05 to ascertain the statistical significance. Additionally, the I2 test was utilized in the further analysis[14]. The details of interpreting I2 values have already been elaborated elsewhere[9].

The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation methodology assessed the quality of evidence about each meta-analysis outcome[15]. The process of creating the summary of findings table and evaluating the quality of evidence as “high”, “moderate”, “low”, or “very low” has been previously described[9].

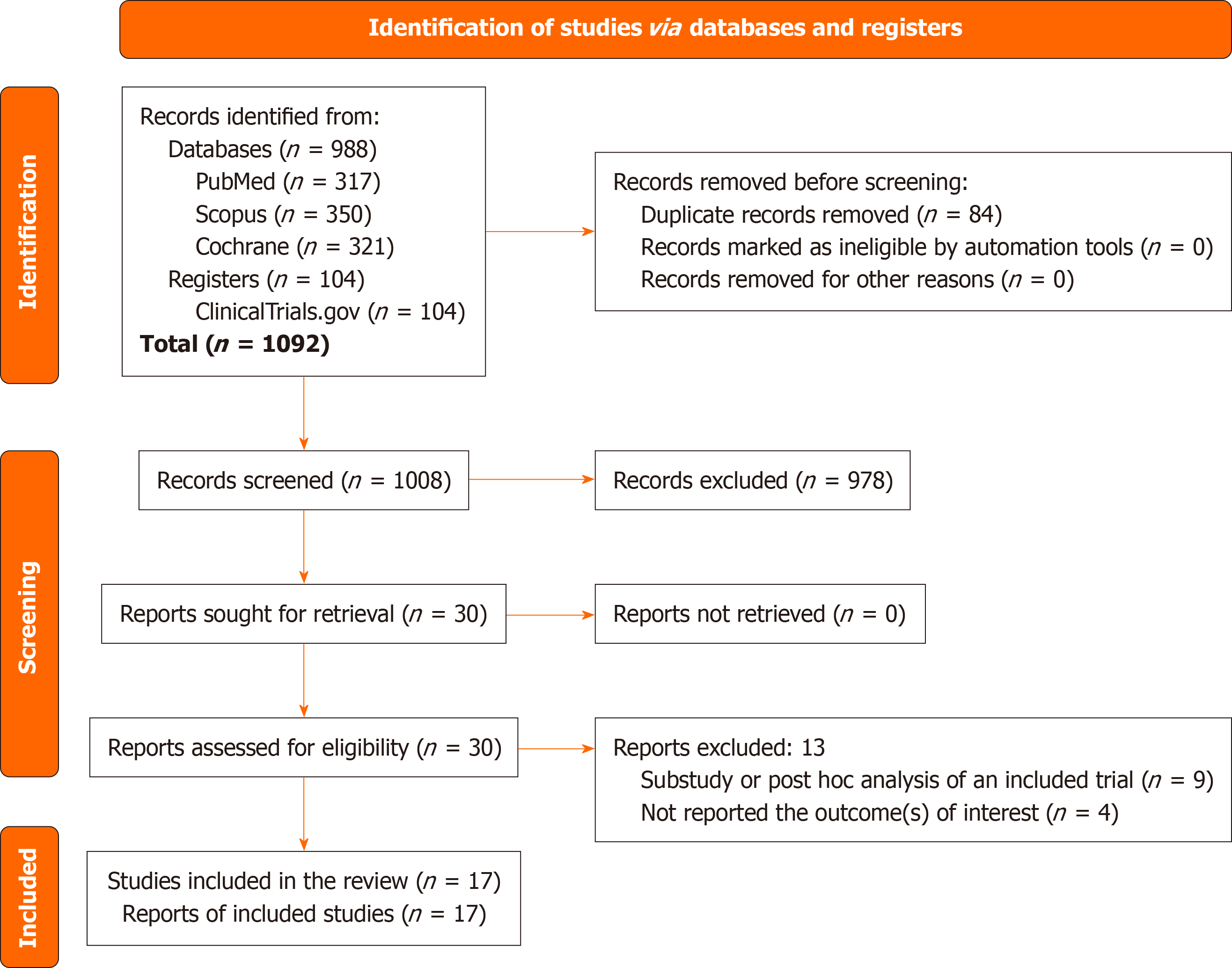

Figure 1 illustrates the study selection process. The initial search identified 1092 articles. Following the screening of titles and abstracts and subsequent full-text reviews, the number of studies considered for this meta-analysis was narrowed to 30. After detailed further evaluation, 17 RCTs involving 14645 subjects, which met all the inclusion criteria were eligible[16-32]. Thirteen studies were excluded. Nine were sub-studies or post-hoc analyses of an included trial[33-41], and the other four studies have not reported the outcomes of interest[42-45].

One of the 17 RCTs included in this meta-analysis was a phase 1 trial[18], while three were phase 2 [16,17,32], and the others were phase 3 trials[19-31]. Twelve trials included individuals with T2D[16-18,20,24-31], four included subjects with obesity/overweight but without diabetes[19,21-23], and the other one included individuals with biopsy-confirmed metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis and fibrosis stages F2 or F3, irrespective of the presence of diabetes[32], as the study population. Ten RCTs used matched placebos[17,19-25,28,32], four used insulin[26,27,29,30], two trials used GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs)[25,31], and the other two used both placebo and GLP-1RA in the control groups[16,18]. Insulin degludec was used in one trial[26], insulin glargine in two trials[27,30], and insulin lispro was used in one trial as active comparators[29]. Two trials used dulaglutide[16,31], and two used semaglutide in the control group[18,25]. Most RCTs had three tirzepatide arms of 5 mg, 10 mg, and 15 mg[18,19,24-32], one had an additional arm of 1 mg[16], two had two arms of 10 mg and 15 mg[20,22], and one trial had single tirzepatide arm of maximum tolerated dose (MTD 10 or 15 mg)[21]. One study (Frias 2020) had one tirzepatide arm of 12 mg (which was analyzed as tirzepatide 10 mg arm) and two arms of tirzepatide 15 mg with different dose-escalation patterns (outcome results were pooled to analyze in a single tirzepatide 15 mg arm)[17]. The SURMOUNT-OSA trial had two different trial populations, each with tirzepatide MTD (10 or 15 mg) and placebo arms. Outcome results of tirzepatide MTD and placebo groups in trials 1 and 2 were pooled into single groups of tirzepatide MTD and placebo[23]. All tirzepatide MTD arms were analyzed as tirzepatide 15 mg. One trial had a 12-week duration[17], one had a 26-week duration[16], one had a 28-week duration[18], four had 40-week durations[24,25,28,30], seven had 52-week durations[22,23,26,27,29,31,32], and the other three spanned 72 weeks[19-21]. The baseline characteristics of the included study subjects were matched throughout the trial arms in all of the included RCTs. Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 present the details of the included and excluded studies, respectively.

Supplementary Figure 1 depicts the bias risk across the 17 RCTs included in the meta-analysis. All (100%) were assessed as having low RoB in terms of random sequence generation (selection bias), allocation concealment (selection bias), and selective reporting (reporting bias). Five of 17 (29%) trials had high risks of blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) and blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias). Only one study (6%) had a high risk of incomplete outcome data (attrition bias). All (100%) had a high risk of other biases. Publication bias was assessed through funnel plots given in Supplementary Figure 2.

The summary of findings table (Supplementary Table 3) provides the grades for the certainty of the evidence supporting the primary outcome of this meta-analysis.

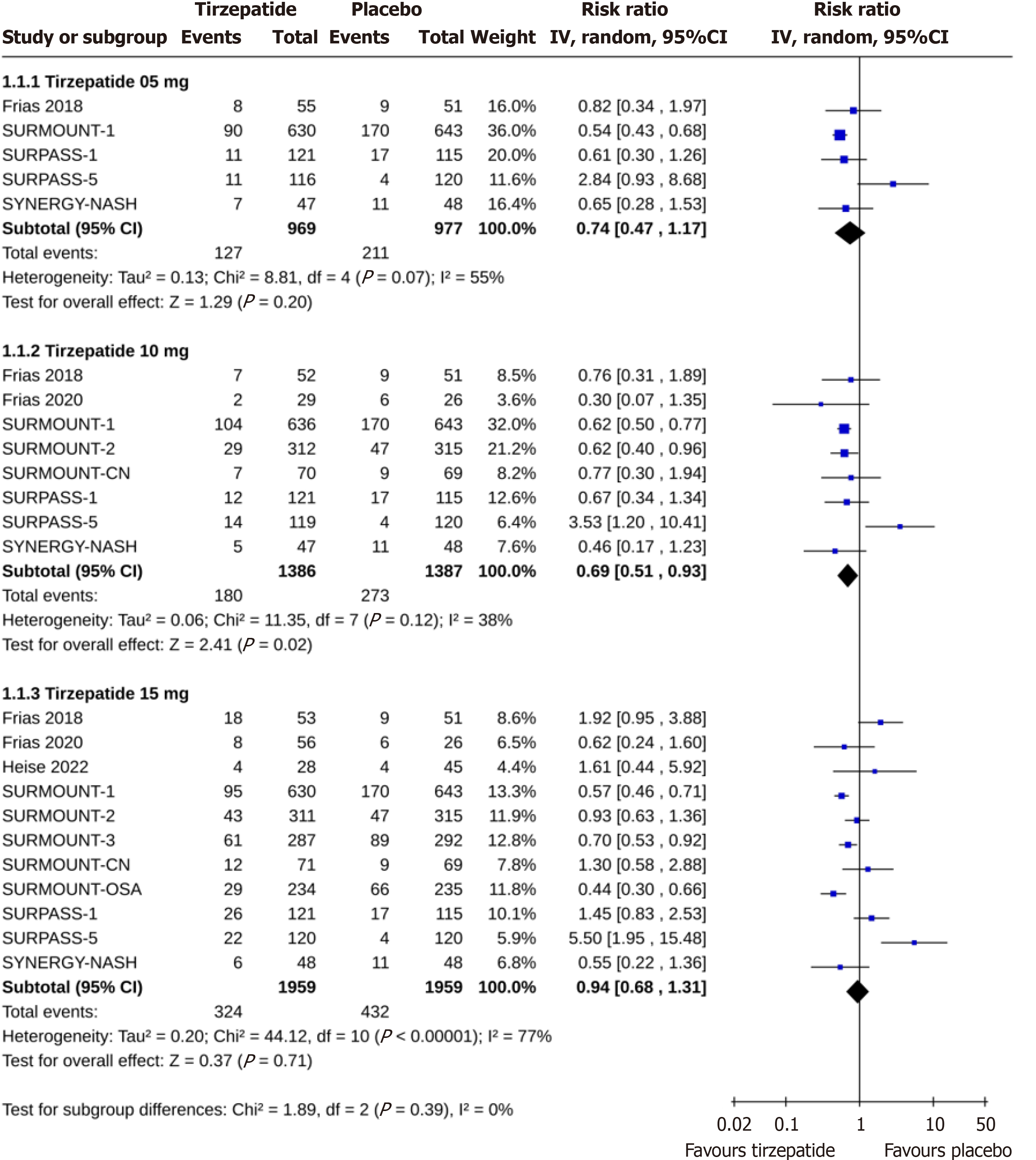

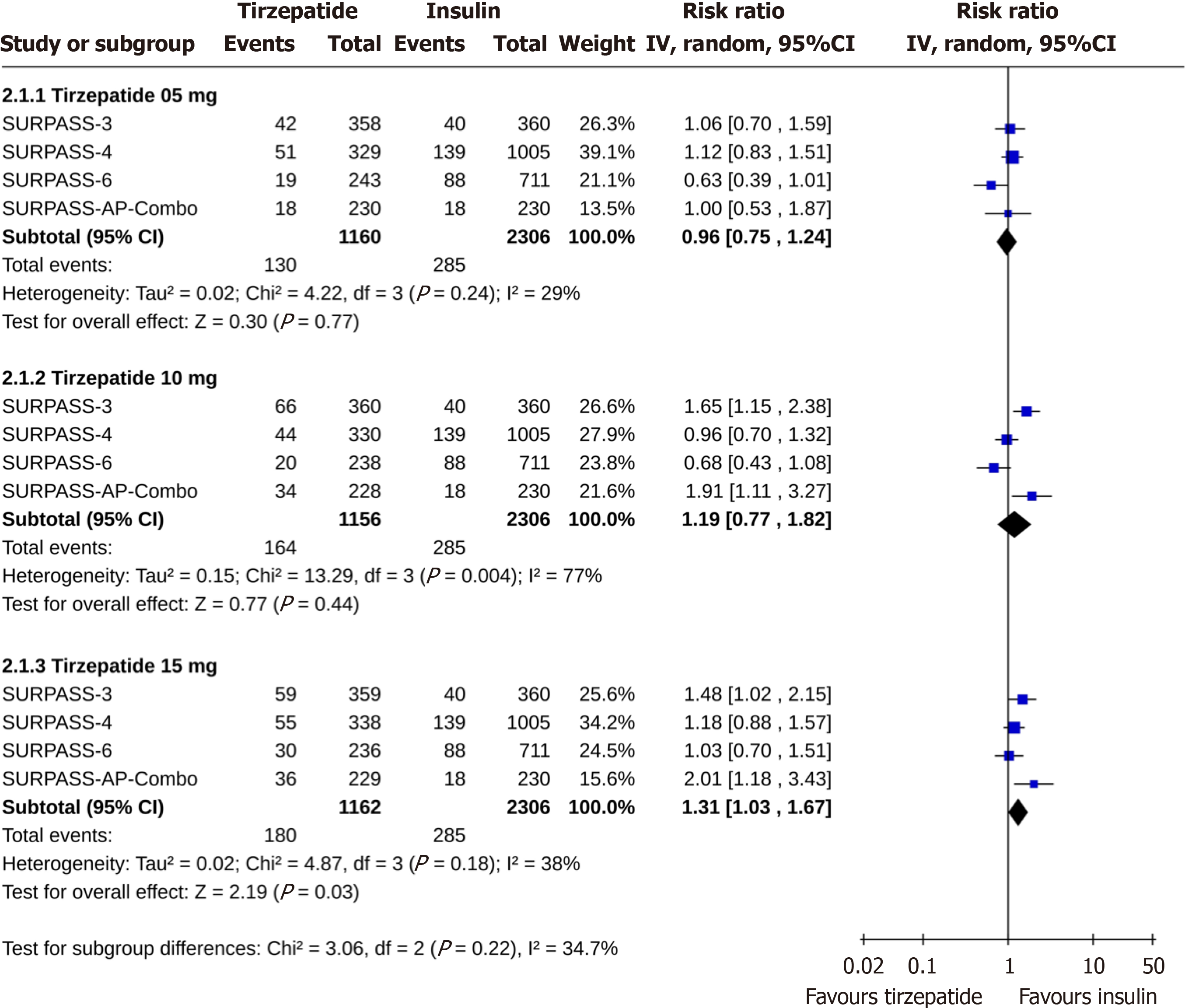

Compared to placebo, there were similar risks of permanent discontinuation of the study drug among study subjects receiving tirzepatide 5 (RR: 0.74, 95%CI: 0.47-1.17, I2 = 55%, P = 0.20) and 15 mg (RR: 0.94, 95%CI: 0.68-1.31, I2 = 77%, P = 0.71). The discontinuation risk was lower with tirzepatide 10 mg (RR: 0.69, 95%CI: 0.51-0.93, I2 = 38%, P = 0.02) than placebo (Figure 2). Tirzepatide at 5 mg 10 mg doses had identical risks of discontinuation than insulin (for tirzepatide 5 mg, RR: 0.96, 95%CI: 0.75-1.24, I2 = 29%, P = 0.77; and for tirzepatide 10 mg, RR: 1.19, 95%CI: 0.77-1.82, I2 = 77%, P = 0.44), whereas the discontinuation risk was higher with tirzepatide 15 mg than insulin (RR: 1.31, 95%CI: 1.03-1.67, I2 = 38%, P = 0.03) (Figure 3). The permanent discontinuation risk was similar among study subjects receiving tirzepatide 5 mg and GLP-1RA (RR: 0.98, 95%CI: 0.70-1.37, I2 = 0%, P = 0.90), although such risks were higher with tirzepatide 10 mg (RR: 1.40, 95%CI: 1.03-1.90, I2 = 0%, P = 0.03) and 15 mg (RR: 1.70, 95%CI: 1.27-2.27, I2 = 0%, P = 0.0004) than GLP-1RA (Figure 4).

Failure to meet randomization criteria: A similar proportion of the subjects in the tirzepatide 15 mg and placebo groups discontinued the study drug due to failure to meet randomization criteria (RR: 0.50, 95%CI: 0.22-1.15, I2 = 0%, P = 0.10). Such reason for discontinuation was similarly observed with all doses of tirzepatide and insulin (for tirzepatide 5 mg, RR: 1.75, 95%CI: 0.07-44.70, I2 = 51%, P = 0.73; for tirzepatide 10 mg: RR: 1.74, 95%CI: 0.07-44.62, I2 = 51%, P = 0.74; and for tirzepatide 15 mg, RR: 0.33, 95%CI: 0.01-8.18, P = 0.50) (Table 1).

| Outcome variables | Control group | Tirzepatide dose | Tirzepatide arm | Control arm | Pooled effect size, RR [95%CI] | I2, % | P value |

| Failure to meet randomization criteria | Placebo | 15 mg | 8/355 | 16/350 | 0.50 [0.22-1.15] | 0 | 0.10 |

| Insulin | 5 mg | 1/687 | 1/1365 | 1.75 [0.07-44.70] | 51 | 0.73 | |

| 10 mg | 1/690 | 1/1365 | 1.74 [0.07-44.62] | 51 | 0.74 | ||

| 15 mg | 0/697 | 1/1365 | 0.33 [0.01-8.18] | NA | 0.50 | ||

| Protocol deviation | Placebo | 5 mg | 0/801 | 4/814 | 0.28 [0.05-1.69] | 0 | 0.16 |

| 10 mg | 3/1217 | 8/1224 | 0.55 [0.17-1.85] | 0 | 0.33 | ||

| 15 mg | 5/1764 | 9/1751 | 0.63 [0.22-1.84] | 0 | 0.40 | ||

| Insulin | 5 mg | 1/687 | 3/1365 | 1.06 [0.12-9.34] | 0 | 0.96 | |

| 10 mg | 1/690 | 3/1365 | 1.02 [0.11-9.73] | NA | 0.99 | ||

| 15 mg | 2/697 | 3/1365 | 1.43 [0.23-9.08] | 0 | 0.70 | ||

| GLP-1RA | 5 mg | 1/685 | 3/682 | 0.43 [0.06-2.93] | 0 | 0.39 | |

| 10 mg | 2/678 | 3/682 | 0.84 [0.15-4.67] | 0 | 0.84 | ||

| 15 mg | 1/683 | 3/682 | 0.43 [0.06-2.92] | 0 | 0.39 | ||

| Adverse events | Placebo | 5 mg | 38/853 | 24/857 | 1.58 [0.95-2.62] | 0 | 0.08 |

| 10 mg | 69/1266 | 38/1267 | 1.74 [1.12-2.71] | 7 | 0.01 | ||

| 15 mg | 133/1841 | 54/1839 | 2.38 [1.55-3.66] | 30 | < 0.001 | ||

| Insulin | 5 mg | 68/1160 | 34/2306 | 3.87 [2.54-5.89] | 0 | < 0.00001 | |

| 10 mg | 101/1156 | 34/2306 | 5.20 [3.47-7.79] | 0 | < 0.00001 | ||

| 15 mg | 118/1162 | 34/2306 | 6.37 [4.31-9.41] | 0 | < 0.00001 | ||

| GLP-1RA | 5 mg | 41/685 | 33/682 | 1.23 [0.79-1.92] | 0 | 0.36 | |

| 10 mg | 55/678 | 33/682 | 1.55 [0.85-2.83] | 39 | 0.16 | ||

| 15 mg | 69/711 | 33/726 | 2.07 [1.39-3.08] | 0 | 0.0003 | ||

| Non-adherence with study treatment | Placebo | 15 mg | 2/292 | 2/261 | 0.68 [0.06-7.42] | 20 | 0.76 |

| Lost to follow up | Placebo | 5 mg | 19/848 | 42/862 | 0.52 [0.25-1.10] | 17 | 0.09 |

| 10 mg | 20/1165 | 49/1177 | 0.42 [0.25-0.70] | 0 | 0.0008 | ||

| 15 mg | 32/1711 | 68/1749 | 0.74 [0.31-1.74] | 57 | 0.49 | ||

| Insulin | 5 mg | 12/930 | 21/2076 | 1.22 [0.58-2.59] | 0 | 0.60 | |

| 10 mg | 9/928 | 21/2076 | 0.93 [0.40-2.18] | 0 | 0.87 | ||

| 15 mg | 8/933 | 21/2076 | 0.84 [0.37 -1.93] | 0 | 0.69 | ||

| GLP-1RA | 5 mg | 4/685 | 10/ 682 | 0.43 [0.14-1.28] | 0 | 0.13 | |

| 10 mg | 5/678 | 10/682 | 0.53 [0.19-1.50] | 0 | 0.23 | ||

| 15 mg | 11/711 | 10/726 | 1.06 [0.46-2.46] | 0 | 0.88 | ||

| Withdrawal by subject | Placebo | 5 mg | 42/848 | 93/862 | 0.83 [0.20-3.34] | 61 | 0.79 |

| 10 mg | 50/1264 | 121/1272 | 0.45 [0.29-0.70] | 15 | 0.0004 | ||

| 15 mg | 74/1840 | 202/1844 | 0.39 [0.26-0.59] | 35 | < 0.00001 | ||

| Insulin | 5 mg | 24/1160 | 135/2306 | 0.35 [0.22-0.54] | 0 | < 0.00001 | |

| 10 mg | 33/1156 | 135/2306 | 0.42 [0.24-0.76] | 45 | 0.004 | ||

| 15 mg | 31/1162 | 135/2306 | 0.46 [0.31-0.69] | 0 | 0.0001 | ||

| GLP-1RA | 5 mg | 10/685 | 10/682 | 0.97 [0.39-2.39] | 0 | 0.94 | |

| 10 mg | 12/678 | 10/682 | 1.20 [0.52-2.79] | 0 | 0.66 | ||

| 15 mg | 16/711 | 11/726 | 1.44 [0.66-3.16] | 0 | 0.36 | ||

| Physician decision | Placebo | 5 mg | 2/677 | 3/691 | 0.75 [0.14-3.99] | 0 | 0.74 |

| 10 mg | 4/1094 | 5/1101 | 0.87 [0.27-2.85] | 0 | 0.82 | ||

| 15 mg | 9/1639 | 10/1628 | 0.83 [0.34-2.04] | 0 | 0.69 | ||

| Insulin | 5 mg | 1/1160 | 22/2306 | 0.23 [0.05-1.00] | 0 | 0.05 | |

| 10 mg | 7/1156 | 22/2306 | 0.80 [0.33-1.91] | 0 | 0.61 | ||

| 15 mg | 8/1162 | 22/2306 | 0.85 [0.24-3.00] | 30 | 0.80 | ||

| GLP-1RA | 5 mg | 0/630 | 2/628 | 0.20 [0.01-4.14] | NA | 0.30 | |

| 10 mg | 7/627 | 2/628 | 2.51 [0.51-12.35] | 6 | 0.26 | ||

| 15 mg | 1/630 | 2/628 | 0.74 [0.05-10.39] | 31 | 0.82 | ||

| Pregnancy | Placebo | 10 mg | 8/1018 | 6/1027 | 1.36 [0.47-3.88] | 0 | 0.57 |

| 15 mg | 9/1533 | 8/1554 | 1.15 [0.45-2.96] | 0 | 0.77 | ||

| Death | Insulin | 5 mg | 15/1160 | 48/2306 | 0.96 [0.54-1.69] | 0 | 0.88 |

| 10 mg | 5/1056 | 48/2306 | 0.37 [0.09-1.48] | 37 | 0.16 | ||

| 15 mg | 7/1162 | 48/2306 | 0.44 [0.20-0.95] | 0 | 0.04 | ||

| Other | Placebo | 5 mg | 5/801 | 20/814 | 0.28 [0.11-0.71] | 0 | 0.007 |

| 10 mg | 7/1217 | 26/1224 | 0.30 [0.14-0.67] | 0 | 0.003 | ||

| 15 mg | 19/1764 | 43/1751 | 0.45 [0.26-0.78] | 0 | 0.004 | ||

| Insulin | 5 mg | 7/1160 | 18/2306 | 0.87 [0.34-2.18] | 0 | 0.76 | |

| 10 mg | 7/1156 | 18/2306 | 1.08 [0.46-2.55] | 0 | 0.86 | ||

| 15 mg | 6/1162 | 18/2306 | 0.83 [0.34-2.04] | 0 | 0.69 | ||

| GLP-1RA | 5 mg | 1/685 | 2/682 | 0.69 [0.11-4.33] | 0 | 0.69 | |

| 10 mg | 3/678 | 2/682 | 1.39 [0.19-10.42] | 14 | 0.75 | ||

| 15 mg | 5/683 | 2/682 | 1.70 [0.13-22.46] | 47 | 0.69 |

Protocol deviation: Protocol deviation was the cause for study drug discontinuation in similar proportions of study subjects receiving tirzepatide vs placebo (for tirzepatide 5 mg, RR: 0.28, 95%CI: 0.05-1.69, I2 = 0%, P = 0.16; for tirzepatide 10 mg, RR: 0.55, 95%CI: 0.17-1.85, I2 = 0%, P = 0.33; and for tirzepatide 15 mg, RR: 0.63, 95%CI: 0.22-1.84, I2 = 0%, P = 0.40) or insulin (for tirzepatide 5 mg, RR: 1.06, 95%CI: 0.12-9.34, I2 = 0%, P = 0.96; for tirzepatide 10 mg, RR: 1.02, 95%CI: 0.11-9.73, P = 0.99; and for tirzepatide 15 mg, RR: 1.43, 95%CI: 0.23-9.08, I2 = 0%, P = 0.70) or GLP-1RA (for tirzepatide 5 mg, RR: 0.43, 95%CI: 0.06-2.93, I2 = 0%, P = 0.39; for tirzepatide 10 mg, RR: 0.84, 95%CI: 0.15-4.67, P = 0.84; and for tirzepatide 15 mg, RR: 0.43, 95%CI: 0.06-2.92, I2 = 0%, P = 0.39) (Table 1).

AEs: The AE-related rate of study drug discontinuation was statistically similar with tirzepatide 5 mg and placebo (RR: 1.58, 95%CI: 0.95-2.62, I2 = 0%, P = 0.08) but was significantly higher with tirzepatide 10 mg (RR: 1.74, 95%CI: 1.12-2.71, I2 = 7%, P = 0.01), and 15 mg (RR: 2.38, 95%CI: 1.55-3.66, I2 = 30%, P < 0.001) than placebo. Such discontinuations were significantly higher with any dose of tirzepatide than insulin (for tirzepatide 5 mg, RR: 3.87, 95%CI: 2.54-5.89, I2 = 0%, P < 0.00001; for tirzepatide 10 mg, RR: 5.20, 95%CI: 3.47-7.79, I2 = 0%, P < 0.00001; and for tirzepatide 15 mg, RR: 6.37, 95%CI: 4.31-9.41, I2 = 0%, P < 0.00001). Tirzepatide 15 mg (RR: 2.07, 95%CI: 1.39-3.08, I2 = 0%, P = 0.0003), but not tirzepatide 5 mg (RR: 1.23, 95%CI: 0.79-1.92, I2 = 0%, P = 0.36) or tirzepatide 10 mg (RR: 1.55, 95%CI: 0.85-2.83, I2 = 39%, P = 0.16) was associated with higher AE-related discontinuation risk than GLP-1RA (Table 1).

Non-adherence with study drug treatment: Non-adherence with treatment was the cause of study drug discontinuation in a similar proportion of subjects who received tirzepatide 15 mg and placebo (RR: 0.68, 95%CI: 0.06-7.42, I2 = 20%, P = 0.76) (Table 1).

Lost to follow-up: Lost to follow-up was the cause for study drug discontinuation in a significantly lower proportion of subjects receiving tirzepatide 10 mg than placebo (RR: 0.42, 95%CI: 0.25-0.70, I2 = 0%, P = 0.0008). Such events were comparable in the intervention groups with tirzepatide 5 mg vs placebo (RR: 0.52, 95%CI: 0.25-1.10, I2 = 17%, P = 0.09), tirzepatide 15 mg vs placebo (RR: 0.74, 95%CI: 0.31-1.74, I2 = 57%, P = 0.49), tirzepatide 5 mg vs insulin (RR: 1.22, 95%CI: 0.58-2.59, I2 = 0%, P = 0.60), tirzepatide 10 mg vs insulin (RR: 0.93, 95%CI: 0.40-2.18, I2 = 0%, P = 0.87), tirzepatide 15 mg vs insulin (RR: 0.84, 95%CI: 0.37-1.93, I2 = 0%, P = 0.69), tirzepatide 5 mg vs GLP-1RA (RR: 0.43, 95%CI: 0.14-1.28, I2 = 0%, P = 0.13), tirzepatide 10 mg vs GLP-1RA (RR: 0.53, 95%CI: 0.19-1.50, I2 = 0%, P = 0.23), and tirzepatide 15 mg vs GLP-1RA (RR: 1.06, 95%CI: 0.46-2.46, I2 = 0%, P = 0.88) (Table 1).

Withdrawal by study participants: Study drug discontinuation due to withdrawal by the study subjects was similar in tirzepatide 5 mg and placebo groups (RR: 0.83, 95%CI: 0.20-3.34, I2 = 61%, P = 0.79) but was significantly lower with tirzepatide 10 mg (RR: 0.45, 95%CI: 0.29-0.70, I2 = 15%, P = 0.0004) and tirzepatide 15 mg (RR: 0.39, 95%CI: 0.26-0.59, I2 = 35%, P < 0.00001) than placebo. Subjects’ withdrawal-related drug discontinuation was significantly lower in all tirzepatide arms than insulin arm (for tirzepatide 5 mg, RR: 0.35, 95%CI: 0.22-0.54, I2 = 0%, P < 0.00001; for tirzepatide 10 mg, RR: 0.42, 95%CI: 0.24-0.76, I2 = 45%, P = 0.004; and for tirzepatide 15 mg, RR: 0.46, 95%CI: 0.31-0.69, I2 = 0%, P = 0.0001). However, the risk of drug discontinuation for the same reason was comparable with any doses of tirzepatide and GLP-1RA (for tirzepatide 5 mg, RR: 0.97, 95%CI: 0.39-2.39, I2 = 0%, P = 0.94; for tirzepatide 10 mg, RR: 1.20, 95%CI: 0.52-2.79, I2 = 0%, P = 0.66; and for tirzepatide 15 mg, RR: 1.44, 95%CI: 0.66-3.16, I2 = 0%, P = 0.36) (Table 1).

Physician decision: Physician decision was the reason of study drug discontinuation in similar proportions of study subjects receiving tirzepatide vs placebo (for tirzepatide 5 mg, RR: 0.75, 95%CI: 0.14-3.99, I2 = 0%, P = 0.74; for tirzepatide 10 mg, RR: 0.87, 95%CI: 0.27-2.85, I2 = 0%, P = 0.82; and for tirzepatide 15 mg, RR: 0.83, 95%CI: 0.34-2.04,

Pregnancy: The proportions of subjects with study drug discontinuation due to pregnancy were identical in the tir

Death: The study drug discontinuation rate due to death was identical in the tirzepatide 5 mg and 10 mg groups to the insulin group (for tirzepatide 5 mg, RR: 0.96, 95%CI: 0.54-1.69, I2 = 0%, P = 0.88; and for tirzepatide 10 mg, RR: 0.37, 95%CI: 0.09-1.48, I2 = 37%, P = 0.16). Death-related study drug discontinuation was lower with tirzepatide 15 mg than insulin (RR: 0.44, 95%CI: 0.20-0.95, I2 = 0%, P = 0.04) (Table 1).

Other causes: Compared to placebo, all doses of tirzepatide were associated with lower study drug discontinuation rates due to other causes (for tirzepatide 5 mg, RR: 0.28, 95%CI: 0.11-0.71, I2 = 0%, P = 0.007; for tirzepatide 10 mg, RR: 0.30, 95%CI: 0.14-0.67, I2 = 0%, P = 0.003; and tirzepatide 15 mg, RR: 0.45, 95%CI: 0.26-0.78, I2 = 0%, P = 0.004). Identical numbers of subjects in the tirzepatide and insulin groups (for tirzepatide 5 mg, RR: 0.87, 95%CI: 0.34-2.18, I2 = 0%, P = 0.76; for tirzepatide 10 mg, RR: 1.08, 95%CI: 0.46-2.55, I2 = 0%, P = 0.86; and tirzepatide 15 mg, RR: 0.83, 95%CI: 0.34-2.04,

This study is the very first in-depth analysis of the reasons for study drug discontinuation in the RCTs with tirzepatide. Based on studies including 17 RCTs, mostly having low RoB and moderate to high certainty of evidence involving 14645 participants, we could identify the reasons for tirzepatide withdrawal among study subjects by this SRM. According to our findings, although higher rates of study drug discontinuation were observed with higher doses of tirzepatide than insulin and GLP-1RA, surprisingly, such rates were relatively lower with tirzepatide compared to placebo. When individual causes were considered, AEs were the most important cause of discontinuation of the study drug. AE-related discontinuation was more frequent with tirzepatide than with control groups, including placebo. Permana et al[4] made similar observations in their previous meta-analysis.

Although permanent discontinuation of the study drug appeared to be less common among the participants in the tirzepatide group, the RR: 0.69 and 95%CI: 0.51-0.93 for the same reached statistical significance only in those receiving 10 mg weekly of the drug [RR (95%CI) for 5 mg and 15 mg weekly: 0.74 (0.47-1.17) and 0.94 (0.68-1.31), respectively]. This could be related to better treatment adherence to 10 mg weekly of tirzepatide dose because of relatively bearable drug side effects and positive treatment effects on T2D and body weight among participants. However, a higher incidence of permanent drug discontinuation was observed among participants on 10 mg [1.19 (0.77-1.82)] and 15 mg [1.31 (1.03-1.67)] doses of tirzepatide compared to insulin, though the risk reached statistical significance only the group on 15 mg of the drug. Intervention with both 10 mg and 15 mg doses of tirzepatide was associated with higher drug discontinuation rates compared to GLP-1RAs [1.40 (1.03-1.90) and 1.70 (1.27-2.27)], respectively - both comparisons were statistically significant]. Slower dose escalation over an extended period may be a strategy for better treatment adherence to tirzepatide, as observed in studies involving semaglutide[46]. Slower and gradual dose up-titration would potentially reduce the adverse effects, especially gastrointestinal intolerance among patients managed by incretin-based agents[47,48].

Interestingly, withdrawal by the study subjects, another important reason for drug discontinuation in RCTs, was less frequent with tirzepatide compared to placebo and insulin. The remarkable improvements in body weight and glycemic control of the tirzepatide intervention group could explain this observation[4,5,49,50]. Marked improvements in clinical outcomes such as obesity and metabolic dysfunction can be rewarding experiences for such participants, encouraging them to adhere to such therapies. A proportion of the study subjects discontinued the drug due to other reasons that were not specifically categorized; such reasons were less frequent in the tirzepatide arms than in the placebo group for the same reason mentioned above.

Statistically significant AEs related to drug discontinuation were observed in the tirzepatide group compared to placebo (except in the 5 mg group - P = 0.08) and insulin, as one would expect, owing to relatively high gastrointestinal side effects with tirzepatide as observed in multiple studies with other incretin molecules[51-53]. However, the discontinuation rate due to AEs was comparable to those on GLP-1RA as evidenced by the results of a recent meta-analysis[53], though we found statistically significant excess risk among those on tirzepatide 15 mg (RR: 2.07, 95%CI: 1.39-3.08). Interestingly, compared to those on insulin, we observed a lower risk of death among those on 15 mg of tirzepatide (RR: 0.44, 95%CI: 0.20-0.95, P = 0.04). Long-term follow-up of patients on tirzepatide would be expected to shed more light on this observation regarding the potential mortality benefit of this new drug molecule.

This is the first comprehensive SRM examining the reasons for drug discontinuation among RCTs using tirzepatide. The certainty of evidence was also reasonably robust to appraise this therapeutic issue encountered by incretin therapy correctly. However, we acknowledge the uncertainties posed by the relatively short follow-up period and the small sample size of the study population, considering the lifelong nature and high prevalence of people with obesity and T2D across the globe. The proportion of participants from ethnically diverse populations was also relatively smaller as most of the RCTs included in this SRM were from Europe and America, another limitation posing uncertainty in the evidence for the generalization of our results. Moreover, the included RCTs were not designed to evaluate specifically the proportion of study subjects with permanent discontinuation of the study drugs and the underlying reason for that as the primary outcomes. Longer-term studies with larger participation and global involvement among different ethnic groups are warranted to curtail these uncertainties.

Although AEs are common reasons for study drug discontinuation and are more frequent with tirzepatide (especially at higher doses) than with placebo, insulin, and GLP-1RA, there are still other causes behind the drug discontinuation. The overall rates of drug discontinuation are comparable, if not lower, than placebo. Larger and longer-term future RCTs with the appropriate involvement of diverse ethnic groups are expected to improve our capability of using this promising drug molecule with excellent disease-modifying properties to manage obesity and T2D with a better evidence-based approach.

We thank Dr. Marina George Kudiyirickal for providing us with the audio core tip for this paper.

| 1. | Coskun T, Sloop KW, Loghin C, Alsina-Fernandez J, Urva S, Bokvist KB, Cui X, Briere DA, Cabrera O, Roell WC, Kuchibhotla U, Moyers JS, Benson CT, Gimeno RE, D'Alessio DA, Haupt A. LY3298176, a novel dual GIP and GLP-1 receptor agonist for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: From discovery to clinical proof of concept. Mol Metab. 2018;18:3-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 538] [Article Influence: 76.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | The United States Food and Drug Administration. New Drug Therapy Approvals 2022, Advancing Health Through Innovation. [cited 30 July 2024]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/novel-drug-approvals-fda/new-drug-therapy-approvals-2022. |

| 3. | The United States Food and Drug Administration. FDA News Release, FDA Approves New Medication for Chronic Weight Management. [cited 30 July 2024]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-medication-chronic-weight-management. |

| 4. | Permana H, Yanto TA, Hariyanto TI. Efficacy and safety of tirzepatide as novel treatment for type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2022;16:102640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dutta D, Kamrul-Hasan ABM, Nagendra L, Bhattacharya S. Efficacy and Safety of Novel Twincretin Tirzepatide, a Dual GIP/GLP-1 Receptor Agonist, as an Anti-obesity Medicine in Individuals Without Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. touchREV Endocrinol. 2024;20:72-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Karagiannis T, Avgerinos I, Liakos A, Del Prato S, Matthews DR, Tsapas A, Bekiari E. Management of type 2 diabetes with the dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist tirzepatide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2022;65:1251-1261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 49.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2nd ed. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2019. |

| 8. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44932] [Cited by in RCA: 40620] [Article Influence: 10155.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 9. | Kamrul-Hasan ABM, Alam MS, Talukder SK, Dutta D, Selim S. Efficacy and Safety of Omarigliptin, a Novel Once-Weekly Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitor, in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2024;39:109-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Higgins JPT, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Sterne JAC. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2nd ed. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2019. |

| 11. | The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan) Version 7.2.0. [cited 30 July 2024]. Available from: revman.cochrane.org. |

| 12. | Song F, Eastwood AJ, Gilbody S, Duley L, Sutton AJ. Publication and related biases. Health Technol Assess. 2000;4:1-115. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Debray TPA, Moons KGM, Riley RD. Detecting small-study effects and funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analysis of survival data: A comparison of new and existing tests. Res Synth Methods. 2018;9:41-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savovic J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JA; Cochrane Bias Methods Group; Cochrane Statistical Methods Group. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18487] [Cited by in RCA: 24863] [Article Influence: 1775.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 15. | Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, Kunz R, Vist G, Brozek J, Norris S, Falck-Ytter Y, Glasziou P, DeBeer H, Jaeschke R, Rind D, Meerpohl J, Dahm P, Schünemann HJ. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:383-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4813] [Cited by in RCA: 7117] [Article Influence: 474.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Frias JP, Nauck MA, Van J, Benson C, Bray R, Cui X, Milicevic Z, Urva S, Haupt A, Robins DA. Efficacy and tolerability of tirzepatide, a dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist in patients with type 2 diabetes: A 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to evaluate different dose-escalation regimens. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22:938-946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 29.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Frias JP, Nauck MA, Van J, Kutner ME, Cui X, Benson C, Urva S, Gimeno RE, Milicevic Z, Robins D, Haupt A. Efficacy and safety of LY3298176, a novel dual GIP and GLP-1 receptor agonist, in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised, placebo-controlled and active comparator-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2018;392:2180-2193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 405] [Cited by in RCA: 558] [Article Influence: 79.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Heise T, Mari A, DeVries JH, Urva S, Li J, Pratt EJ, Coskun T, Thomas MK, Mather KJ, Haupt A, Milicevic Z. Effects of subcutaneous tirzepatide versus placebo or semaglutide on pancreatic islet function and insulin sensitivity in adults with type 2 diabetes: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, parallel-arm, phase 1 clinical trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022;10:418-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 45.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jastreboff AM, Aronne LJ, Ahmad NN, Wharton S, Connery L, Alves B, Kiyosue A, Zhang S, Liu B, Bunck MC, Stefanski A; SURMOUNT-1 Investigators. Tirzepatide Once Weekly for the Treatment of Obesity. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:205-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 1532] [Article Influence: 510.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Garvey WT, Frias JP, Jastreboff AM, le Roux CW, Sattar N, Aizenberg D, Mao H, Zhang S, Ahmad NN, Bunck MC, Benabbad I, Zhang XM; SURMOUNT-2 investigators. Tirzepatide once weekly for the treatment of obesity in people with type 2 diabetes (SURMOUNT-2): a double-blind, randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2023;402:613-626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 294] [Article Influence: 147.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wadden TA, Chao AM, Machineni S, Kushner R, Ard J, Srivastava G, Halpern B, Zhang S, Chen J, Bunck MC, Ahmad NN, Forrester T. Tirzepatide after intensive lifestyle intervention in adults with overweight or obesity: the SURMOUNT-3 phase 3 trial. Nat Med. 2023;29:2909-2918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 79.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zhao L, Cheng Z, Lu Y, Liu M, Chen H, Zhang M, Wang R, Yuan Y, Li X. Tirzepatide for Weight Reduction in Chinese Adults With Obesity: The SURMOUNT-CN Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2024;332:551-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 34.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Malhotra A, Grunstein RR, Fietze I, Weaver TE, Redline S, Azarbarzin A, Sands SA, Schwab RJ, Dunn JP, Chakladar S, Bunck MC, Bednarik J; SURMOUNT-OSA Investigators. Tirzepatide for the Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Obesity. N Engl J Med. 2024;391:1193-1205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 189.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rosenstock J, Wysham C, Frías JP, Kaneko S, Lee CJ, Fernández Landó L, Mao H, Cui X, Karanikas CA, Thieu VT. Efficacy and safety of a novel dual GIP and GLP-1 receptor agonist tirzepatide in patients with type 2 diabetes (SURPASS-1): a double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;398:143-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 552] [Article Influence: 138.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Frías JP, Davies MJ, Rosenstock J, Pérez Manghi FC, Fernández Landó L, Bergman BK, Liu B, Cui X, Brown K; SURPASS-2 Investigators. Tirzepatide versus Semaglutide Once Weekly in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:503-515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 312] [Cited by in RCA: 985] [Article Influence: 246.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ludvik B, Giorgino F, Jódar E, Frias JP, Fernández Landó L, Brown K, Bray R, Rodríguez Á. Once-weekly tirzepatide versus once-daily insulin degludec as add-on to metformin with or without SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with type 2 diabetes (SURPASS-3): a randomised, open-label, parallel-group, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;398:583-598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 362] [Article Influence: 90.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Del Prato S, Kahn SE, Pavo I, Weerakkody GJ, Yang Z, Doupis J, Aizenberg D, Wynne AG, Riesmeyer JS, Heine RJ, Wiese RJ; SURPASS-4 Investigators. Tirzepatide versus insulin glargine in type 2 diabetes and increased cardiovascular risk (SURPASS-4): a randomised, open-label, parallel-group, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;398:1811-1824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 370] [Article Influence: 92.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Dahl D, Onishi Y, Norwood P, Huh R, Bray R, Patel H, Rodríguez Á. Effect of Subcutaneous Tirzepatide vs Placebo Added to Titrated Insulin Glargine on Glycemic Control in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: The SURPASS-5 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2022;327:534-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 340] [Article Influence: 113.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Rosenstock J, Frías JP, Rodbard HW, Tofé S, Sears E, Huh R, Fernández Landó L, Patel H. Tirzepatide vs Insulin Lispro Added to Basal Insulin in Type 2 Diabetes: The SURPASS-6 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2023;330:1631-1640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 35.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Gao L, Lee BW, Chawla M, Kim J, Huo L, Du L, Huang Y, Ji L. Tirzepatide versus insulin glargine as second-line or third-line therapy in type 2 diabetes in the Asia-Pacific region: the SURPASS-AP-Combo trial. Nat Med. 2023;29:1500-1510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Inagaki N, Takeuchi M, Oura T, Imaoka T, Seino Y. Efficacy and safety of tirzepatide monotherapy compared with dulaglutide in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes (SURPASS J-mono): a double-blind, multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022;10:623-633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 41.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Loomba R, Hartman ML, Lawitz EJ, Vuppalanchi R, Boursier J, Bugianesi E, Yoneda M, Behling C, Cummings OW, Tang Y, Brouwers B, Robins DA, Nikooie A, Bunck MC, Haupt A, Sanyal AJ; SYNERGY-NASH Investigators. Tirzepatide for Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis with Liver Fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2024;391:299-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 299] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 252.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Battelino T, Bergenstal RM, Rodríguez A, Fernández Landó L, Bray R, Tong Z, Brown K. Efficacy of once-weekly tirzepatide versus once-daily insulin degludec on glycaemic control measured by continuous glucose monitoring in adults with type 2 diabetes (SURPASS-3 CGM): a substudy of the randomised, open-label, parallel-group, phase 3 SURPASS-3 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022;10:407-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Cariou B, Linge J, Neeland IJ, Dahlqvist Leinhard O, Petersson M, Fernández Landó L, Bray R, Rodríguez Á. Effect of tirzepatide on body fat distribution pattern in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2024;26:2446-2455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Gastaldelli A, Cusi K, Fernández Landó L, Bray R, Brouwers B, Rodríguez Á. Effect of tirzepatide versus insulin degludec on liver fat content and abdominal adipose tissue in people with type 2 diabetes (SURPASS-3 MRI): a substudy of the randomised, open-label, parallel-group, phase 3 SURPASS-3 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022;10:393-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 287] [Article Influence: 95.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Heerspink HJL, Sattar N, Pavo I, Haupt A, Duffin KL, Yang Z, Wiese RJ, Tuttle KR, Cherney DZI. Effects of tirzepatide versus insulin glargine on kidney outcomes in type 2 diabetes in the SURPASS-4 trial: post-hoc analysis of an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022;10:774-785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 48.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Hartman ML, Sanyal AJ, Loomba R, Wilson JM, Nikooienejad A, Bray R, Karanikas CA, Duffin KL, Robins DA, Haupt A. Effects of Novel Dual GIP and GLP-1 Receptor Agonist Tirzepatide on Biomarkers of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:1352-1355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 47.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 38. | Pirro V, Roth KD, Lin Y, Willency JA, Milligan PL, Wilson JM, Ruotolo G, Haupt A, Newgard CB, Duffin KL. Effects of Tirzepatide, a Dual GIP and GLP-1 RA, on Lipid and Metabolite Profiles in Subjects With Type 2 Diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107:363-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Thomas MK, Nikooienejad A, Bray R, Cui X, Wilson J, Duffin K, Milicevic Z, Haupt A, Robins DA. Dual GIP and GLP-1 Receptor Agonist Tirzepatide Improves Beta-cell Function and Insulin Sensitivity in Type 2 Diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106:388-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 46.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Wilson JM, Nikooienejad A, Robins DA, Roell WC, Riesmeyer JS, Haupt A, Duffin KL, Taskinen MR, Ruotolo G. The dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist, tirzepatide, improves lipoprotein biomarkers associated with insulin resistance and cardiovascular risk in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22:2451-2459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Wilson JM, Lin Y, Luo MJ, Considine G, Cox AL, Bowsman LM, Robins DA, Haupt A, Duffin KL, Ruotolo G. The dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist tirzepatide improves cardiovascular risk biomarkers in patients with type 2 diabetes: A post hoc analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2022;24:148-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 25.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Feng P, Sheng X, Ji Y, Urva S, Wang F, Miller S, Qian C, An Z, Cui Y. A Phase 1 Multiple Dose Study of Tirzepatide in Chinese Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Adv Ther. 2023;40:3434-3445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Furihata K, Mimura H, Urva S, Oura T, Ohwaki K, Imaoka T. A phase 1 multiple-ascending dose study of tirzepatide in Japanese participants with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2022;24:239-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Kadowaki T, Chin R, Ozeki A, Imaoka T, Ogawa Y. Safety and efficacy of tirzepatide as an add-on to single oral antihyperglycaemic medication in patients with type 2 diabetes in Japan (SURPASS J-combo): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, parallel-group, phase 3 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022;10:634-644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Urva S, Coskun T, Loh MT, Du Y, Thomas MK, Gurbuz S, Haupt A, Benson CT, Hernandez-Illas M, D'Alessio DA, Milicevic Z. LY3437943, a novel triple GIP, GLP-1, and glucagon receptor agonist in people with type 2 diabetes: a phase 1b, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised, multiple-ascending dose trial. Lancet. 2022;400:1869-1881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 37.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Kushner RF, Calanna S, Davies M, Dicker D, Garvey WT, Goldman B, Lingvay I, Thomsen M, Wadden TA, Wharton S, Wilding JPH, Rubino D. Semaglutide 2.4 mg for the Treatment of Obesity: Key Elements of the STEP Trials 1 to 5. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2020;28:1050-1061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 37.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Nauck MA, Quast DR, Wefers J, Meier JJ. GLP-1 receptor agonists in the treatment of type 2 diabetes - state-of-the-art. Mol Metab. 2021;46:101102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 399] [Cited by in RCA: 865] [Article Influence: 216.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Gill L, Mackey S. Obstetrician-Gynecologists' Strategies for Patient Initiation and Maintenance of Antiobesity Treatment with Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2021;30:1016-1027. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Cui Y, Yao J, Qiu X, Guo C, Kong D, Dong J, Liao L. Comparative Efficacy and Safety of Tirzepatide in Asians and Non-Asians with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diabetes Ther. 2024;15:781-799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Ayesh H, Suhail S, Ayesh S, Niswender K. Comparative efficacy and safety of weekly tirzepatide versus weekly insulin in type 2 diabetes: A network meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2024;26:3801-3809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Lin F, Yu B, Ling B, Lv G, Shang H, Zhao X, Jie X, Chen J, Li Y. Weight loss efficiency and safety of tirzepatide: A Systematic review. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0285197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Yanto TA, Vatvani AD, Hariyanto TI, Suastika K. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist and new-onset diabetes in overweight/obese individuals with prediabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2024;18:103069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Kommu S, Berg RL. Efficacy and safety of once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide on weight loss in patients with overweight or obesity without diabetes mellitus-A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev. 2024;25:e13792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |