Published online Apr 15, 2025. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v16.i4.101310

Revised: December 17, 2024

Accepted: February 12, 2025

Published online: April 15, 2025

Processing time: 170 Days and 4.7 Hours

The trend of risk prediction models for diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) is increasing, but few studies focus on the quality of the model and its practical application.

To conduct a comprehensive systematic review and rigorous evaluation of pre

A meticulous search was conducted in PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane, CNKI, Wang Fang DATA, and VIP Database to identify studies published until October 2023. The included and excluded criteria were applied by the researchers to screen the literature. Two investigators independently extracted data and assessed the quality using a data extraction form and a bias risk assessment tool. Disagree

The systematic review included 14 studies with a total of 26 models. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of the 26 models was 0.629-0.938. All studies had high risks of bias, mainly due to participants, outcomes, and analysis. The most common predictors included glycated hemoglobin, age, duration of diabetes, lipid abnormalities, and fasting blood glucose.

The predictor model presented good differentiation, calibration, but there were significant methodological flaws and high risk of bias. Future studies should focus on improving the study design and study report, updating the model and verifying its adaptability and feasibility in clinical practice.

Core Tip: This study conducted a systematic review and comprehensive evaluation of 26 prediction models for diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) from 14 studies. Despite demonstrating satisfactory differentiation and calibration, the predictor models were found to exhibit significant methodological deficiencies and high risks of bias, primarily related to participant selection, outcome measurement, and data analysis. The most common identified predictors were glycated hemoglobin, age, diabetes duration, lipid abnormalities, and fasting blood glucose. Future research should prioritize improving study design and reporting, updating DPN prediction models, and validating their clinical adaptability and feasibility, which is crucial for enhancing the reliability and practical application of these models.

- Citation: Sun CF, Lin YH, Ling GX, Gao HJ, Feng XZ, Sun CQ. Systematic review and critical appraisal of predictive models for diabetic peripheral neuropathy: Existing challenges and proposed enhancements. World J Diabetes 2025; 16(4): 101310

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v16/i4/101310.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v16.i4.101310

Diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN), as the most common diabetes complication, has an insidious onset and often affects the patient's sensory and motor nerves, inducing pain and numbness in limbs[1]. According to the International Diabetes Federation, the global diabetes prevalence was estimated to be 10.5% in 2021, and is expected to rise to 12.2% in 2045, when 783.2 million people will suffer from the disease[2]. With diabetes prevalence rising, DPN incidence also increases, affecting over 50% of people with diabetes[3]. The lower limb amputation rate in diabetic patients is 10 times higher than in non-diabetic patients, and has now been shown to be a major contributing factor to death in diabetic patients[4].

Early detection, rigorous management of high-risk patients, and prompt interventions are vital in managing DPN. There are numerous risk factors for DPN[5], and risk prediction models constructed based on these factors can facilitate early screening and targeted prevention. Based on the positive effects of risk prediction models, scholars globally have developed different risk prediction models for DPN. Predictive models are crucial in clinical decision-making. By incorporating patient-specific data such as glycemic control, duration of diabetes, and comorbidities, these models enable doctors to customize their management strategies, ensuring that interventions are targeted and personalized. In terms of clinical decision-making, predictive models have the potential to inform personalized treatment plans, and facilitate early interventions.

However, the quality of research on DPN predictive models varies, with some models lacking robustness in validation, transparency in methodology, and generalizability, which limits the popularization and application of the models in the clinic to a certain extent. These quality variations can impact clinical utility and reliability. Therefore, it’s imperative to assess the predictive models for DPN, ensuring their clinical relevance and reliability.

The Prediction model Risk of Bias Assessment Tool (PROBAST) is a tool developed by a steering group that considers existing risk of bias (ROB) tools and reporting guidelines to assess the ROB and applicability of diagnostic and prognostic prediction model studies. We conducted a systematic evaluation of relevant studies on risk prediction models for DPN onset, describing the characteristics of model development, including predictors, prediction endpoints, representation forms, and external validation. Our assessment focused on the bias risk and practicality of these models, considering participants, predictors, outcomes, and analysis. The aim is to identify well-performing risk prediction models for clinical use and provide a reference for early detection of DPN patients.

This study adhered to the guidelines for conducting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of prediction models and examined studies on prediction models by utilizing the Checklist for critical appraisal and data extraction for systematic Reviews of prediction Modelling Studies (CHARMS)[6,7]. Additionally, this study has been registered with PROSPERO, the international prospective registry of systematic reviews (registration number: CRD42023462706).

We conducted a comprehensive search of PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, CNKI, Wang Fang DATA, and VIP Database from the time of library construction to October 1, 2023, for English and Chinese primary articles reporting on the development and validation of models predicting DPN. Search terms included "Diabetic peripheral neuropathy", "prediction model", "risk prediction", "predictors", "risk factors", and "predictive tools". Additional search details are provided in Supplementary material.

Two independent researchers screened titles and abstracts, followed by a full-text evaluation. All prediction modeling studies, whether with or without external validation, and external validation studies, whether with or without model updating, were included if they satisfied the predefined inclusion criteria outlined in PICOTS.

P (population): Patients diagnosed with DPN, particularly those with type 2 diabetes and aged ≥ 18 years.

I (intervention model): Studies focus on prediction models that were internally or externally validated, specifically for prognostic models predicting the risk of DPN.

C (comparator): None

O (outcome): DPN.

T (timing): Outcomes were predicted after the diagnosis of DPN, with no restriction on the time frame of the prediction.

S (setting): The intended use of the prediction model was to perform risk stratification in the assessment of amputation development in medical institutions, such that preventive measures could be used.

The aim of our search was to identify studies that included predictive models that primarily predicted the risk of DPN. We excluded literature that only studied independent risk factors without modeling, informally published literature, reviews, meta-analysis, or basic experiments. Study screening consisted of three main steps. Firstly, we imported the search results into EndNote X9 and removed duplicates. Then, we further screened based on titles and abstracts (Step 2) and read the full text (Step 3). Two researchers independently screened the literature based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any study discrepancies were resolved by consensus and, if necessary, through a third reviewer.

Following literature selection, a data extraction form was developed using the CHARMS Checklist. Extracted data included the first author, publication date, study type, data source, population, follow-up duration, outcome indexes, model construction status, candidate variable status, missing data handling, modeling methodology, variable selection, predictive efficacy, calibration methods, internal/external validation, and model presentation form.

We utilized PROBAST to evaluate the bias risk and applicability of the study[8,9]. The bias risk assessment includes 20 issues across four domains: Study design, predictors, outcomes, and analysis. Any high-risk or unclear rating within these domains was considered indicative of overall high bias risk. This involved assessing the suitability of study population selection, rationality of inclusion/exclusion criteria, definition and measurement of predictor variables, outcome classifications and definitions, etc. The applicability evaluation includes three domains: Study object, predictor, and outcome, and any one domain rated as low applicability is considered as overall low applicability.

Two researchers independently extracted data and assessed the quality of each included study. Disagreements were resolved through discussion or, if consensus could not be reached, by consulting a third investigator.

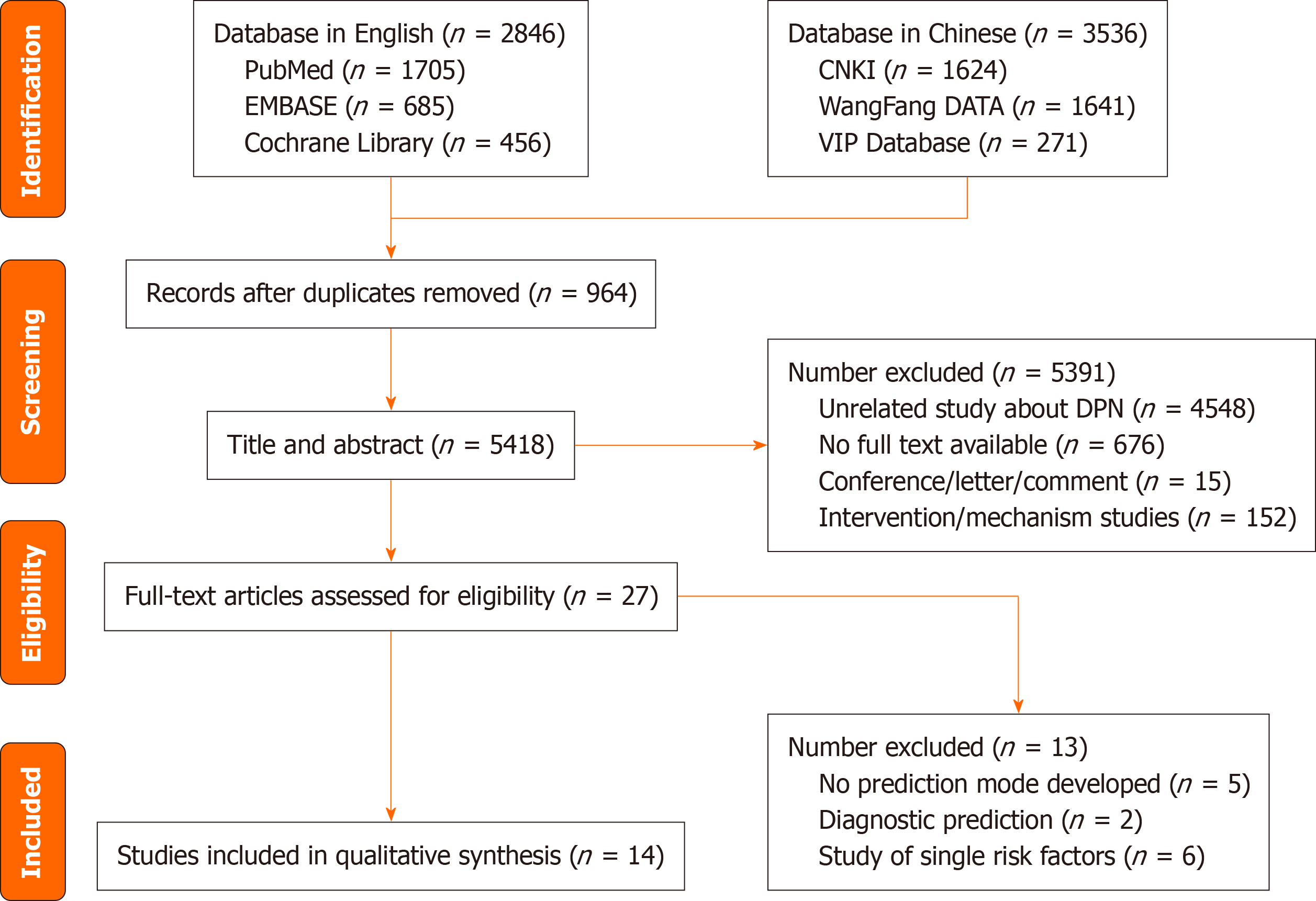

As shown in Figure 1, the search strategy identified 6382 relevant articles, and after the title and abstract were screened, 27 studies were retained for the full test evaluation and 14[10-23] studies were eventually incorporated by reading the full text.

Most of DPN prediction models were conducted in China and 12 studies were published in the past 4 years. The studies contained 26 predictive models, with 11 studies[10-18,20,22] using logistic regression methods for modeling and 5 studies[14,16,21-23] taking different kinds of machine learning algorithms for modeling. Among them, Lian et al[16] took 5 different kinds of machine learning algorithms and Fan et al[21] took 7 different kinds of machine learning algorithms to select the optimal model. Of 3 studies[14,16,22] performed both machine learning algorithms and logistic regression methods for modeling. The predictive outcome of the included articles is the occurrence of DPN. The basic characteristics of the included articles are shown in Table 1.

| Year | Ref. | Country | Design | Type of model (D/V) | Collecting time | Sample size (D/V) | Outcome measure | Age (SD) (years) |

| 2019 | Ning et al[11] | China | Case-control study | D | January 2017-June 2018 | 452/- | DPN occurs | 53.62 ± 12.79 |

| 2020 | Metsker et al[22] | Russia | Cross-sectional study | D, V | July 2010-August 2017 | 4340/1085 | DPN occurs | - |

| 2021 | Wu et al[17] | China | Prospective cohort study | D, V | September 2018-July 2019 | 460/152 | DPN occurs | 65 |

| 2021 | Fan et al[21] | China | Real-world study | D, V | January 2010-December 2015 | 132/33 | DPN occurs | - |

| 2022 | Zhang et al[18] | China | Case-control study | D, V | February 2017-May 2021 | 519/259 | DPN occurs | D: 57.76 ± 12.95; V: 58.97 ± 12.49 |

| 2022 | Li et al[10] | China | Retrospective cohort study | D, V | 2010-2019 | 11265/3755 | DPN occurs | 60.3 ± 10.9 |

| 2023 | Tian et al[20] | China | Cross-sectional study | D, V | January 2019-October 2020 | 3297/1426 | DPN occurs | - |

| 2023 | Li et al[15] | China | Retrospective cohort study | D, V | D: January 2017-December 2020; V: January 2019-December 2020 | 3012/901 | DPN occurs | D: 57.12 ± 12.23; V: 56.60 ± 12.03 |

| 2023 | Lian et al[16] | China | Retrospective cohort study | D, V | February 2020-July 2022 | 895/383 | DPN occurs | 64.5 (55.0–72.0) |

| 2023 | Liu et al[19] | China | Retrospective cohort study | D, V | September 2010-September 2020 | 95604/462 | DPN occurs | 52.4 ± 12.2 |

| 2023 | Wang et al[12] | China | Case-control study | D | March 2021-March 2023 | 500/- | DPN occurs | 56.8 ± 10.22 |

| 2023 | Zhang et al[13] | China | Case-control study | D | April 2019-May 2020 | 323/- | DPN occurs | 55.36 ± 11.25 |

| 2023 | Gelaw et al[14] | Ethiopia | Prospective cohort study | D | January 2005-December 2021 | 808/- | DPN occurs | 45.6 ± 3.1 |

| 2022 | Baskozos et al[23] | Multi center | Cross-sectional study | D, V | 2012-2019 | 935/295 | Painful or painless DPN occurs | D: 68 (60-74); V: 69 (63-77) |

The study encompasses 14 articles, with potential predictor variables ranging from 5 to 11. Notably, 3 studies[14,20,21] categorized continuous variables into two or more categories. The sample size ranges from 165 to 15020 cases, with outcome events ranging from 122 to 6133 cases. Among the included studies, the study conducted by Li et al[15] has the largest sample size. Regarding missing data, 3 studies[14,16,23] performed multiple imputation, while the remaining studies excluded subjects with missing data. In terms of predictor variable selection, 4 studies[11,12,18,21] initially conducted monofactor analysis and included predictor variables with statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) into regression analysis for model development.

The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) for 26 models, ranging from 0.629 to 0.938, was reported in 14 studies. All models, except those by Wu et al[17] and Zhang et al[13] with AUCs of 0.629 and 0.647, demonstrated high discrimination (AUC ≥ 0.80).

There are 9 studies[11-15,17-18,20,23] presenting calibration, primarily through calibration curves. Model validation was conducted in all 14 studies, with 8 studies[10-15,18,21] performing internal validation by Bootstrap, 4 studies[16,20,22,23] performing cross-validation, and 4 studies[15,17,19,23] performing external validation. Li et al[15] and Baskozos et al[23] employed a combination of internal and external validation. In terms of prediction model presentation, 9 studies[10-15,17-18,20] were mostly shown as Nomogram, these studies were mostly presented in the form of Nomogram and estimated the risk rate based on the score. Table 2 depicts the modeling.

| Ref. | Modeling method | Variable selection methods | Methods for handling continuous variables | Missing data | Predictors in the final model | Model performance | Model presentation | Internal validation | External validation | ||

| Quantity | Processing method | Discrimination | Calibration | ||||||||

| Ning et al[11] | Logistic regression | Monofactor analysis | Maintaining continuity | - | - | Duration of DM/FPG/FINS/HbA1c/HOMA-IR/Vaspin/Omentin-1 | AUC = 0.789 (0.741-0.873) | Calibration curve | Nomogram | Bootstrap | None |

| Metsker et al[22] | Artificial neural network/support vector machine/decision tree/linear regression/logistic regression | - | - | - | Delete, replace | Unsatisfactory control of glycemia/systemic inflammation/renal dyslipidemia/dyslipidemia/macroangiopathy | (1) AUC = 0.8922; (2) AUC = 0.8644; (3) AUC = 0.8988; (4) AUC = 0.8926; and (5) AUC = 0.8941 | None | LIME explanation | 5-fold cross-validation | None |

| Wu et al[17] | Logistic regression | LASSO regression | Maintaining continuity | 19 | - | FBG/PBG/LDL-C/age/TC/BMI/HbA1c | D: (1) AUC = 0.656; (2) AUC = 0.724; (3) AUC = 0.731; and (4) AUC = 0.713. V: (1) AUC = 0.629; (2) AUC = 0.712; (3) AUC = 0.813; and (4) AUC = 0.830 | Hosmer-Lemeshow test/Calibration Plot | Nomogram | None | Geographical |

| Fan et al[21] | Machine learning | Monofactor analysis | Categorizing continuous variables | - | - | Age/duration of DM/duration of unadjusted hypoglycemic treatment (≥ 1 year)/number of insulin species/total cost of hypoglycemic drugs/number of hypoglycemic drugs/gender/genetic history of diabetes/dyslipidemia | (1) XF: AUC = 0.847 ± 0.081; (2) CHAID: AUC = 0.787 ± 0.081; (3) QUEST: AUC = 0.720 ± 0.06; and (4) D: AUC = 0.859 ± 0.05 | None | Variable Importance | Bootstrap | None |

| Zhang et al[18] | Logistic regression | Monofactor analysis | Maintaining continuity | - | - | Age/gender/duration of DM/BMI/uric acid/HbA1c/FT3 | D: AUC = 0.763; V: AUC = 0.755 | Calibration curve | Nomogram | Bootstrap | None |

| Li et al[10] | Logistic regression | LASSO regression | Maintaining continuity | - | - | Sex/age/DR/duration of DM/WBC/eosinophil fraction/lymphocyte count/HbA1c/GSP/TC/TG/HDL/LDL/ApoA1/ApoB | D: AUC = 0.858 (0.851-0.865); V: AUC = 0.852 (0.840-0.865) | Hosmer-Lemeshow Test/Calibration curve | Nomogram | Bootstrap | None |

| Tian et al[20] | Logistic regression | LASSO regression | Categorizing continuous variables | - | - | Advanced age of grading/smoking/insomnia/sweating/loose teeth/dry skin/purple tongue | D: AUC = 0.727; V: AUC = 0.744 | Calibration curve | Nomogram | 5-fold cross-validation | None |

| Li et al[15] | Logistic regression | LASSO regression | Maintaining continuity | - | - | Age/25(OH)D3/duration of T2DM/HDL/HbA1c/FBG | D: AUC = 0.8256 (0.8104-0.8408); V: AUC = 0.8608 (0.8376-0.8840) | Hosmer-lemeshow test/Calibration curve | Nomogram | Bootstrap | Geographical |

| Lian et al[16] | Logistic regression machine learning | - | Maintaining continuity | 10 | Delete, multiple imputation, or leave unprocessed | Age/ALT/ALB/TBIL/UREA/TC/HbA1c/APTT/24-hUTP/urine protein concentration/duration of DM/neutrophil-to-lymphocyte Ratio/HOMA-IR | AUC = 0.818 | None | The Shapley additive explanations | 10-fold cross-validation | None |

| Liu et al[19] | Β coefficient | - | Maintaining continuity | - | - | Age/smoking/BMI/duration of DM/HbA1c/low HDL-c/high TG/hypertension/DR/DKD/CVD | AUC = 0.831 (0.794-0.868) | None | - | None | Geographical |

| Wang et al[12] | Logistic regression | Monofactor analysis | Maintaining continuity | - | - | Age/duration of DM/HbA1c/TG/2 hours CP/T3 | AUC = 0.938 (0.918-0.958) | Hosmer-lemeshow test/Calibration curve | Nomogram | Bootstrap | None |

| Zhang et al[13] | Logistic regression | LASSO regression | Maintaining continuity | - | - | Age/smoking/dyslipidemia/HbA1c/glucose variability parameters | AUC = 0.647 (0.585-0.708) | Hosmer-lemeshow test/Calibration curve | Nomogram | Bootstrap | None |

| Gelaw et al[14] | Logistic regression/machine learning | LASSO regression | Categorizing continuous variables | - | Multiple Imputation | Hypertension/FBG/other comorbidities/Alcohol consumption/Physical activity/type of DM treatment/WBC/RBC | (1) AUC = 0.732 (0.69-0.773); and (2) AUC = 0.702 (0.658-0.746) | Hosmer-lemeshow test | Nomogram | Bootstrap | None |

| Baskozos et al[23] | Machine learning | - | - | - | Multiple imputation | Quality of life (EQ5D)/lifestyle (smoking, alcohol consumption)/demographics (age, gender)/personality and psychology traits (anxiety, depression, personality traits)/biochemical (HbA1c)/clinical variables (BMI, hospital stay and trauma at young age) | (1) AUC = 0.8184 (0.8167-0.8201); (2) AUC = 0.8188 (0.8171-0.8205); and (3) AUC = 0.8123 (0.8107-0.8140) | Calibration curve | The adaptive regression splines classifier | 10-fold cross-validation | Geographical |

The number of predictors included in each study ranged from 5 to 11, categorized into demographic, physical examination, and laboratory examination indicators. The top 5 predictors that appeared more frequently were glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), age, duration of diabetes, dyslipidemia, and fasting blood glucose (FBG). In addition, the goal of the study by Tian et al[20] was to determine the predictors of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) clinical indicators in DPN patients, so the included predictors were mainly Chinese medicine indicators.

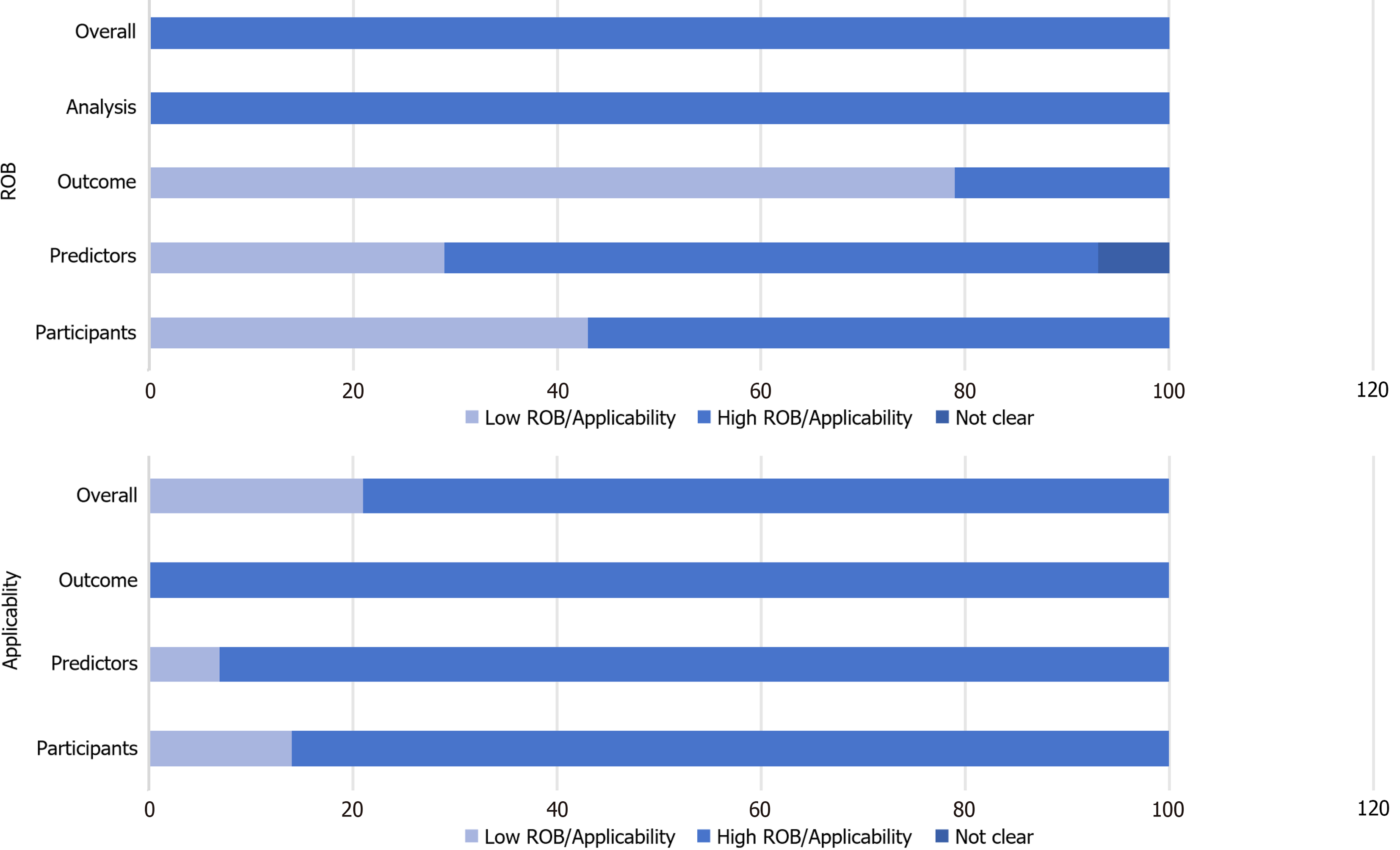

The research conducted a qualitative evaluation of the bias risk and applicability of the inclusion of the literature in accordance with the PROBAST evaluation criteria[8,9], and the study as a whole showed high bias risks and better applicability (Tables 3 and 4, Figure 2).

| Ref. | Discrimination | Sensibility | Specificity | Precision | F1 score | Recall rate | Accuracy | PPV | NPV |

| Ning et al[11] | AUC = 0.789 (0.741-0.873) | ||||||||

| Metsker et al[22] | (1) AUC = 0.8922; (2) AUC = 0.8644; (3) AUC = 0.8988; (4) AUC = 0.8926; and (5) AUC = 0.8941 | (1) ANN = 0.6736; (2) SVM = 0.6817; (3) Decision tree = 0.6526; (4) Linear Regression = 0.6777; and (5) Logistic Regression = 0.6826 | (1) ANN = 0.7342; (2) SVM = 0.7210; (3) Decision tree = 0.6865; (4) Linear Regression = 0.7299; and (5) Logistic Regression = 0.7232 | (1) ANN = 0.8090; (2) SVM = 0.7655; (3) Decision tree = 0.7302; (4) Linear Regression = 0.7911; and (5) Logistic Regression = 0.7693 | (1) ANN = 0.7471; (2) SVM = 0.7443; (3) Decision tree = 0.7039; (4) Linear Regression = 0.7472; and (5) Logistic Regression = 0.7384 | ||||

| Wu et al[17] | D: (1) AUC = 0.656; (2) AUC = 0.724; (3) AUC = 0.731; and (4) AUC = 0.713; V; (1) AUC = 0.629; (2) AUC = 0.712; (3) AUC = 0.813; and (4) AUC = 0.830 | ||||||||

| Fan et al[21] | (1) XF: AUC = 0.847 ± 0.081; (2) CHAID: AUC = 0.787 ± 0.081; (3) QUEST: AUC = 0.720 ± 0.06; and (4) D: AUC = 0.859 ± 0.05 | (1) XF: 0.783 ± 0.080; (2) CHAID: 0.757 ± 0.054; (3) QUEST: 0.766 ± 0.056; and (4) D: 0.843 ± 0.038 | (1) XF: 0.642 ± 0.123; (2) CHAID: 0.680 ± 0.143; (3) QUEST: 0.716 ± 0.186; and (4) D: 0.775 ± 0.092 | (1) XF: 0.882 ± 0.073; (2) CHAID: 0.807 ± 0.070; (3) QUEST: 0.805 ± 0.057; and (4) D: 0.885 ± 0.055 | |||||

| Zhang et al[18] | D: AUC = 0.763; V: AUC = 0.755 | ||||||||

| Li et al[10] | D: AUC = 0.858 (0.851-0.865); V: AUC = 0.852 (0.840-0.865) | 0.74 | 0.874 | ||||||

| Tian et al[20] | D: AUC = 0.727; V: AUC = 0.744 | ||||||||

| Li et al[15] | D: AUC = 0.8256 (0.8104-0.8408); V: AUC = 0.8608 (0.8376-0.8840) | ||||||||

| Lian et al[16] | LR: 0.683 (0.586, 0.737); (2) KNN: 0.671 (0.607, 0.739); (3) DT: 0.679 (0.636, 0.759); (4) NB: 0.589 (0.543, 0.634); (5) RF: 0.736 (0.686,0.765); and (6) XGBoost: 0.764 (0.679, 0.801) | (1) LR: 0.687 ± 0.056; (2) KNN: 0.858 ± 0.070; (3) DT: 0.695 ± 0.032; (4) NB: 0.784 ± 0.087; (5) RF: 0.769 ± 0.026; and (6) XGBoost: 0.765 ± 0.040 | (1) LR: 0.672 ± 0.056; (2) KNN: 0.559 ± 0.070; (3) DT: 0.669 ± 0.042; (4) NB: 0.378 ± 0.071; (5) RF: 0.719 ± 0.027; and (6) XGBoost: 0.736 ± 0.050 | (1) LR: 0.659 ± 0.062; (2) KNN: 0.419 ± 0.073; (3) DT: 0.648 ± 0.067; (4) NB: 0.253 ± 0.061; (5) RF: 0.677 ± 0.040; and (6) XGBoost: 0.711 ± 0.066 | (1) LR: 0.679 ± 0.052; (2) KNN: 0.674 ± 0.039; (3) DT: 0.682 ± 0.032; (4) NB: 0.590 ± 0.029; (5) RF: 0.736 ± 0.021; and (6) XGBoost: 0.746 ± 0.041 | ||||

| Liu et al[19] | AUC = 0.831 (0.794-0.868) | ||||||||

| Wang et al[12] | AUC = 0.938 (0.918-0.958) | 0.846 | 0.668 | ||||||

| Zhang et al[13] | AUC = 0.647 (0.585-0.708) | ||||||||

| Gelaw et al[14] | (1) AUC = 0.732 (0.69-0.773); and (2) AUC = 0.702 (0.658-0.746) | (1): 0.652; and (2): 0.7209 | (1): 0.717; and (2): 0.577 | (1) 0.384; and (2) 0.315 | (1) 0.884; and (2) 0.884 | ||||

| Baskozos et al[23] | (1) AUC = 0.8184 (0.8167-0.8201); (2) AUC = 0.8188 (0.8171-0.8205); and (3) AUC = 0.8123 (0.8107-0.8140) |

| Ref. | Risk of bias | Applicability | Overall | ||||||

| Participants | Predictors | Outcome | Analysis | Participants | Predictors | Outcome | Risk of bias | Applicability | |

| Ning et al[11] | + | - | + | - | - | + | + | - | - |

| Metsker et al[22] | - | - | + | - | + | + | + | - | + |

| Wu et al[17] | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | + |

| Fan et al[21] | - | - | + | - | + | + | + | - | + |

| Zhang et al[18] | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | - | + |

| Li et al[10] | - | - | + | - | + | + | + | - | + |

| Tian et al[20] | - | ? | - | - | + | - | - | - | - |

| Li et al[15] | - | - | + | - | + | + | + | - | + |

| Lian et al[16] | - | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | + |

| Liu et al[19] | - | - | - | - | + | + | + | - | + |

| Wang et al[12] | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | + |

| Zhang et al[13] | + | - | + | - | - | + | + | - | - |

| Gelaw et al[14] | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | + |

| Baskozos et al[23] | - | - | + | - | + | + | + | - | + |

Domain 1: Bias in study population: After evaluation, 8 studies[10,15-16,19-23] exhibited a high bias risk, which was attributed to the high ROB in the model of the retrospective study during the establishment and validation process, and some of the studies had a diagnosis of DPN prior to inclusion, which may have led to a higher estimation of the predictive performance of the model. Fan et al's study[21] was also diagnosed with DPN prior to inclusion, and was therefore classified as high bias risk.

Domain 2: Bias in predictive factors: Differences in the definition and measurement of predictors lead to a high ROB. Most of the models were single-center studies, with 9 studies[10-11,13,15,18-19,21-23] showing high bias risk because the assessors of predictors were not blinded and it is unclear whether the researchers assessed the predictive factors with knowledge of the occurrence of DPN. The ROB for Tian et al[20] was unclear because the predictors were subjectively judged by different assessors. Conversely, 2 prospective studies[14,17] demonstrated low bias, as they detailed predictor mea

Domain 3: Bias in outcome evaluation: Tian et al[20] used TCM syndrome and tongue indicators to assess DPN risk, potentially overestimating the association between predictors and outcomes, as well as an overestimation of model performance. In the item " Determining whether the information on the predictive factors is not clear in the outcome?", In this item, Liu et al[19] determined the predictors selected for the final model by including 18 cohort studies of DPN for model derivation, and thus was at high ROB. Similarly, Zhang et al[18] incorporated body mass index (BMI) as a pre

Domain 4: Bias related to analysis: All studies exhibited high bias risk or unclear status due to the following reasons:

(1) Sample size: Fan et al[21] had insufficient sample size or events per variable < 20, which did not meet the re

(2) Variable treatment: 3 studies[14,20,21] classified continuous variables without specifying the grouping criteria in advance. 9[10-13,15-19] studies maintained the continuity of variables without any processing, and 2 studies[22,23] did not report the handling method for continuous variables;

(3) Missing data: 3 studies[14,16,23] processed missing values through multiple imputation, and 2 studies[16,22] deleted some of the missing data, which could lead to higher data bias for incorporation into the analysis. The remaining studies did not provide relevant information regarding missing data;

(4) Variable selection: 4 studies[11,12,18,21] used monofactor analysis to initially screen the predictors and did not analyze them in combination with other variables, which may cause bias due to the omission of independent variables;

(5) Model performance: 4 studies[16,19,21,22] did not report model calibration assessment;

And (6) Model validation: 8 studies[10-15,18,21] conducted internal validation, with only 2 studies[15,23] conducting both internal and external validation. The remaining studies employed either cross-validation or external validation.

Regarding applicability, 3 studies[11,13,20] exhibited limited applicability, particularly concerning predictors and study populations. Ning et al[11] incorporated unconventional indicators like homeostasis model assessment of insulin re

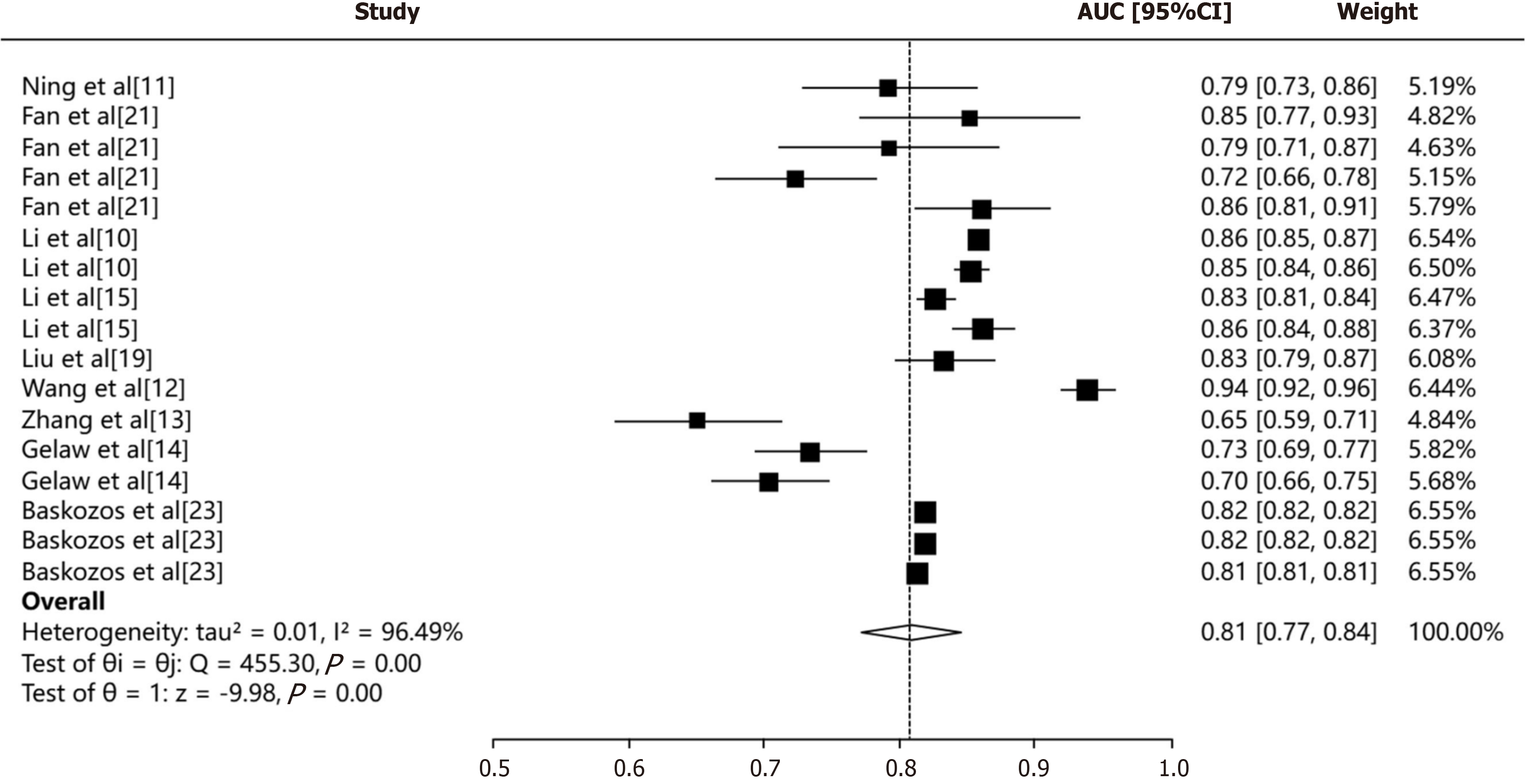

In terms of model performance, a critical determinant factor is the quality and completeness of training and validation data. Inconsistencies in data collection, along with missing values, can significantly impact the ability to achieve a pooled discrimination metric (CI). We used the random-effects model to pool all AUCs (Figure 3) The pooled AUC was 0.81 (95%CI: 0.77-0.84). The I2 value was 96.49% (P < 0.001), suggesting a high heterogeneity.

The predictive models for DPN demonstrated robust performance and significant clinical relevance. Currently, there is an increasing attention in clinical practice towards constructing and utilizing these models, particularly for DPN risk prediction in diabetes patients. In this study, we systematically reviewed relevant research on DPN risk prediction models and included a total of 14 articles with 26 prediction models. Logistic regression analysis was the most commonly used method for modeling. Notably, 9 studies exhibited high discrimination (AUC ≥ 0.80), indicating favorable discriminative ability of the models. However, 10 studies[10-14,16,18,20-22] did not conduct external validation, which affected the generalizability of the models.

The quality of risk prediction models is closely related to research design, modeling methods, and statistical analysis[9]. Most included prediction models lacked rigorous research design, and the overall quality assessment of methodological aspects was suboptimal. 8 studies[10-15,18,21] conducted internal validation after model construction. Fur

Overall, Gelaw et al's model[14] construction process is relatively comprehensive. Based on a large-scale multi-center study in the Amhara region of Ethiopia (2005-2021), it aims to predict DPN risk in diabetics patients. The study addressed missing data with multiple imputation, used LASSO regression for predictor selection, and conducted multi-variable logistic regression analysis and machine learning algorithms to build the model. The model's performance was assessed using AUC and calibration plots, along with internal validation and decision curve analysis to evaluate its net benefit. The results indicated that after internal validation, the χ2 was 0.717 for multivariate logistic regression and 0.702 for machine learning, suggesting that the model has a substantial net benefit in both nomograms and categorical regression trees. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test (P = 0.3077 > 0.05) indicated that the model was well fitted. However, Wu et al's model[17] exhibited suboptimal performance. We attributed this limited predictive capacity primarily to the inclusion of factors with relatively weak associations with DPN, such as age, BMI, FBG, estimated glomerular filtration rate, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, etc. This finding underscores the importance of carefully selecting variables with strong correlations to the outcome when developing predictive models.

Due to variations in research types and included variables, the predictors incorporated in different studies are not identical, but there are certain commonalities. Among the 14 studies included, the most frequently recurring predictive factors are HbA1c, age, diabetes duration, dyslipidemia, and FBG. These factors consistently appear in multiple models and significantly impact on the output of the models. Notably, despite some predictive factors are controversial, they are widely recognized as risk factors for DPN in diabetic patients. In clinical practice, assessing these common factors is crucial for identifying high-risk patients. Future research should focus on exploring more controllable factors that can be improved through interventions to further enhance patient outcomes.

Furthermore, we recognize the potential of novel biomarkers and histological data as predictors in future models. As research advances, the identification of new biomarkers and the development of advanced imaging techniques may offer deeper insights into DPN mechanisms and enhance risk model predictability. Incorporating data such as gut microbiota, metabolomic profiles[23,24], and imaging changes in brain structure and function via magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography[25,26] could provide more personalized and accurate risk assessments. However, predictive models that integrate these factors are yet to be established, indicating a promising direction for future research to guide more effective interventions and ultimately improve patient outcomes.

Integrating DPN predictive models into clinical practice is also a challenge, requiring user-friendly tools and clear interpretive guidance for clinicians. Collaboration among researchers, clinicians, and healthcare administrators is vital for effective implementation. Education on model interpretation and application, supported by online tutorials and clinical decision support systems, is crucial for model interpretation and application. Integration of models into electronic health records or clinical information systems facilitates real-time risk assessment and personalized care. Predictive models should align with clinical judgment and patient preferences, considering overall health and personal values. Continuous monitoring and feedback are essential for model refinement.

Currently, most DPN risk prediction models have a high ROB. Based on the results of this study, the following insights can be applied to future research practice:

Study type selection: Regarding the selection of study subjects, suitable data sources should be chosen for model con

Predictor definition and measurement: For predictors in studies, a consistent approach to definition and measurement is crucial, particularly when subjective judgments (e.g., imaging findings, patient symptoms) are involved, as this can lead to higher bias among different measures. We expect more precise and practical proposals for identifying predictors of DPN, incorporating statistical methods. Furthermore, if more reliable predictors are discovered, they should be incorporated into medical assessments, follow-ups, guidelines, and fully integrated into clinical practice.

Data statistical analysis: In data statistical analysis, overfitting models can occur due to inadequate sample size and low events per variable. To address this issue, integrating data resources to boost sample size or using internal validation methods for quantitative assessment can help minimize bias.

Predictor variables: When dealing with predictor variables, converting continuous variables into categorical variables can result in information loss and reduced model predictive ability. Thus, maintaining the continuity of continuous variables is advisable. If it is necessary to convert them into categorical variables, clear categorization principles and justifications should be established in advance.

Missing values: Research has demonstrated that improper handling of missing data can adversely affect results and model performance. Thus, in dealing with missing values, it is important to comprehensive analysis of missing data reasons and impacts. To mitigate these effects, imputation methods, weighted methods, and other techniques, is essential for stable statistical analysis and model performance.

Model validation: The clinical prediction models' application value lies not just in their predictive performance but also in their generalizability and clinical applicability. Internal validation of prediction models is used to test their reproducibility and guards against overfitting, while external validation assesses the model's transportability and generalizability[26]. Consequently, both internal and external validation are crucial for ensuring the reliability of prediction models. To enhance the generalizability of DPN predictive models, the following strategies can be implemented: Utilization of large, diverse datasets across institutions and demographics to capture DPN variability; rigorous data preprocessing and feature engineering for optimized performance; application of advanced machine learning, including deep learning, to boost accuracy; integration of clinical factors and biomarkers, such as electromyography scores, to augment predictive power; and ongoing model evaluation and updates to adapt to emerging DPN data and research findings.

Model evaluation: Numerous studies neglected assessing the model's discrimination and calibration (often relying on the Hosmer-Lemeshow test), revealing substantial methodological flaws. Therefore, when evaluating models, it is essential to comprehensively consider both discrimination and calibration, and to use multiple evaluation metrics to obtain more reliable and comprehensive results. By optimizing research methods and data processing, the models will be con

Multi-center prospective databases: Existing studies are primarily single-center and retrospective, susceptible to in

Model advancement: The current study on DPN is primarily based on cross-sectional studies. Future research ad

The strengths of this review lie in its comprehensive retrieval of DPN prediction models, selection of relevant studies, and extraction of key data, including predictive factors, outcomes, and study populations. The study systematically evaluated these models using rigorous methods, including pre-registration, standardized research and reporting via CHARMS, and adherence to PROBAST criteria. This approach ensured the effectiveness and reliability of the results, providing valuable insights for future model development.

However, several potential limitations should be noted. Firstly, by searching only English and Chinese databases, the review may have omitted models in other languages, introducing publication bias. Secondly, diagnostic criteria variations led to inconsistent predictors, modeling methods, and evaluation indexes, complicating meta-analysis. Thirdly, direct model comparability is limited due to the lack of relevant study method information in the included studies. Fourthly, most studies included were conducted in China, thereby limiting their geographical applicability. Considering significant differences in lifestyle, environmental conditions, dietary habits, and medical practices across regions, the findings may not be directly applicable to clinical practice globally. Moreover, numerous studies included incomplete or inaccurate data, especially regarding patient lifestyle, comorbidities, and glycemic control histories. Reliance on potentially in

Future research should address these limitations by utilizing larger, more diverse datasets, applying advanced data preprocessing techniques, and incorporating a broader spectrum of clinical and non-clinical factors to enhance model predictive accuracy and generalizability.

In this study, we systematically evaluated neuropathy risk prediction modeling research, assessing models based on research object, prediction performance, modeling/validation methods, predictors, and presentation form. The results indicated that existing DPN risk models are still in the developmental stage. While most of models exhibit good predictive performance, there is a certain ROB, and some predictors remain controversial. These studies bridge a significant gap in the literature by conducting a comprehensive evaluation of DPN prediction models. By identifying methodological flaws and high bias risks, we have outlined key areas for improvement to guide future research. Specifically, future model development should prioritize enhancing research design through multicenter, large-sample studies ensuring generalizability, reliability, and robust clinical decision-making frameworks. Model validation should be strengthened using cross-validation techniques and external studies on new data. During construction, adherence to PROBAST guidelines is crucial to minimize bias and ensure scientific rigor. Future research should explore novel predictors, such as genetic and biomarker data, and methodologies, including machine learning, to enhance predictive performance. Additionally, User-friendly and interpretable models are essential to boost their clinical applicability and adoption. Enhanced predictive accuracy and reliability of DPN models can facilitate better patient care decisions, enabling earlier interventions and superior outcomes.

| 1. | Cai Z, Yang Y, Zhang J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the serum lipid profile in prediction of diabetic neuropathy. Sci Rep. 2021;11:499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S, Pinkepank M, Ogurtsova K, Duncan BB, Stein C, Basit A, Chan JCN, Mbanya JC, Pavkov ME, Ramachandaran A, Wild SH, James S, Herman WH, Zhang P, Bommer C, Kuo S, Boyko EJ, Magliano DJ. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;183:109119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3033] [Cited by in RCA: 4815] [Article Influence: 1605.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (36)] |

| 3. | Pop-Busui R, Boulton AJ, Feldman EL, Bril V, Freeman R, Malik RA, Sosenko JM, Ziegler D. Diabetic Neuropathy: A Position Statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:136-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1426] [Cited by in RCA: 1439] [Article Influence: 179.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Nativel M, Potier L, Alexandre L, Baillet-Blanco L, Ducasse E, Velho G, Marre M, Roussel R, Rigalleau V, Mohammedi K. Lower extremity arterial disease in patients with diabetes: a contemporary narrative review. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17:138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Liu X, Xu Y, An M, Zeng Q. The risk factors for diabetic peripheral neuropathy: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0212574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Moons KG, de Groot JA, Bouwmeester W, Vergouwe Y, Mallett S, Altman DG, Reitsma JB, Collins GS. Critical appraisal and data extraction for systematic reviews of prediction modelling studies: the CHARMS checklist. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001744. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1043] [Cited by in RCA: 1240] [Article Influence: 112.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Debray TP, Damen JA, Snell KI, Ensor J, Hooft L, Reitsma JB, Riley RD, Moons KG. A guide to systematic review and meta-analysis of prediction model performance. BMJ. 2017;356:i6460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 279] [Cited by in RCA: 351] [Article Influence: 43.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wolff RF, Moons KGM, Riley RD, Whiting PF, Westwood M, Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Kleijnen J, Mallett S; PROBAST Group†. PROBAST: A Tool to Assess the Risk of Bias and Applicability of Prediction Model Studies. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170:51-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 999] [Cited by in RCA: 1359] [Article Influence: 226.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Moons KGM, Wolff RF, Riley RD, Whiting PF, Westwood M, Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Kleijnen J, Mallett S. PROBAST: A Tool to Assess Risk of Bias and Applicability of Prediction Model Studies: Explanation and Elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170:W1-W33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 667] [Cited by in RCA: 882] [Article Influence: 147.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Li YS, Zhang XL, Li C, Feng ZW, Wang K. [A Predictive Nomogram for the Risk of Peripheral Neuropathy in Type 2 Diabetes]. Zhongguo Quanke Yixue. 2022;25:675-681. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Ning GJ, Shi L, Deng WJ, Liu HY, Gu J, Ren WD, Hao WF. [Predictive nomogram model for diabetic peripheral neuropathy]. Xiandai Yufang Yixue. 2019;46:798-803. |

| 12. | Wang Y. [Construction of a nomogram predictive model for the risk of peripheral neuropathy in type 2 diabetes]. M.Sc. Thesis, Xinjiang Medical University. 2023. Available from: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/thesis/D03042496. |

| 13. | Zhang F, Guo WC, Tan H, Yin HJ, Peng LP, Zhao Y, Li HF. [Development and Validation of Risk Predicting Model for Severe Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy Based on Glucose Variability Parameters]. Kunming Yike Daxue Xuebao. 2023;44:53-59. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Gelaw NB, Muche AA, Alem AZ, Gebi NB, Chekol YM, Tesfie TK, Tebeje TM. Development and validation of risk prediction model for diabetic neuropathy among diabetes mellitus patients at selected referral hospitals, in Amhara regional state Northwest Ethiopia, 2005-2021. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0276472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Li Y, Li Y, Deng N, Shi H, Caika S, Sen G. Training and External Validation of a Predict Nomogram for Type 2 Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13:1265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lian X, Qi J, Yuan M, Li X, Wang M, Li G, Yang T, Zhong J. Study on risk factors of diabetic peripheral neuropathy and establishment of a prediction model by machine learning. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2023;23:146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wu B, Niu Z, Hu F. Study on Risk Factors of Peripheral Neuropathy in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Establishment of Prediction Model. Diabetes Metab J. 2021;45:526-538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zhang W, Chen L. A Nomogram for Predicting the Possibility of Peripheral Neuropathy in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Brain Sci. 2022;12:1328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Liu X, Chen D, Fu H, Liu X, Zhang Q, Zhang J, Ding M, Wen J, Chang B. Development and validation of a risk prediction model for early diabetic peripheral neuropathy based on a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1128069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tian Z, Fan Y, Sun X, Wang D, Guan Y, Zhang Y, Zhang Z, Guo J, Bu H, Wu Z, Wang H. Predictive value of TCM clinical index for diabetic peripheral neuropathy among the type 2 diabetes mellitus population: A new observation and insight. Heliyon. 2023;9:e17339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Fan Y, Long E, Cai L, Cao Q, Wu X, Tong R. Machine Learning Approaches to Predict Risks of Diabetic Complications and Poor Glycemic Control in Nonadherent Type 2 Diabetes. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:665951. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Metsker O, Magoev K, Yakovlev A, Yanishevskiy S, Kopanitsa G, Kovalchuk S, Krzhizhanovskaya VV. Identification of risk factors for patients with diabetes: diabetic polyneuropathy case study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2020;20:201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Baskozos G, Themistocleous AC, Hebert HL, Pascal MMV, John J, Callaghan BC, Laycock H, Granovsky Y, Crombez G, Yarnitsky D, Rice ASC, Smith BH, Bennett DLH. Classification of painful or painless diabetic peripheral neuropathy and identification of the most powerful predictors using machine learning models in large cross-sectional cohorts. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2022;22:144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lan Z, Wei Y, Yue K, He R, Jiang Z. Genetically predicted immune cells mediate the association between gut microbiota and neuropathy pain. Inflammopharmacology. 2024;32:3357-3373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wang LQ, Yue JH, Gao SL, Cao DN, Li A, Peng CL, Liu X, Han SW, Li XL, Zhang QH. Magnetic resonance imaging on brain structure and function changes in diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Front Neurol. 2023;14:1285312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Selvarajah D, Sloan G, Teh K, Wilkinson ID, Heiberg-Gibbons F, Awadh M, Kelsall A, Grieg M, Pallai S, Tesfaye S. Structural Brain Alterations in Key Somatosensory and Nociceptive Regions in Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy. Diabetes Care. 2023;46:777-785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 27. | Wang W, Ji Q, Ran X, Li C, Kuang H, Yu X, Fang H, Yang J, Liu J, Xue Y, Feng B, Lei M, Zhu D. Prevalence and risk factors of diabetic peripheral neuropathy: A population-based cross-sectional study in China. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2023;39:e3702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Jiang A, Li J, Wang L, Zha W, Lin Y, Zhao J, Fang Z, Shen G. Multi-feature, Chinese-Western medicine-integrated prediction model for diabetic peripheral neuropathy based on machine learning and SHAP. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2024;40:e3801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kessler JA, Shaibani A, Sang CN, Christiansen M, Kudrow D, Vinik A, Shin N; VM202 study group. Gene therapy for diabetic peripheral neuropathy: A randomized, placebo-controlled phase III study of VM202, a plasmid DNA encoding human hepatocyte growth factor. Clin Transl Sci. 2021;14:1176-1184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |