Published online Apr 15, 2025. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v16.i4.100638

Revised: December 17, 2024

Accepted: January 22, 2025

Published online: April 15, 2025

Processing time: 190 Days and 18.1 Hours

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a rapidly growing global health emergency of the 21st century. Comorbidities, such as DM and depression, are common, presenting challenges to the healthcare system.

To investigate the prevalence of depression and its associated factors in patients with DM and to strengthen the management of depression in this patient group.

Participants were selected from the 2018 China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale, with a score of 10 or more indicating depression. Group differences were compared using analysis of variance and χ2 tests. Binary logistic regression was conducted to explore the odds ratios (ORs) of independent variables. Following Andersen’s behavioral model, predisposing, enabling, health need, and health behavior variables were introduced stepwise into the logistic model.

Of the 1673 patients with diabetes, 41.4% had depressive symptoms. Regarding the predisposing characteristics, patients who were male (OR 0.426, P < 0.05), married (OR 0.634, P < 0.05), and received a high school education or higher (OR 0.432, P < 0.05) reported fewer depressive symptoms. Healthcare needs, including better self-rated health (OR 0.458 for fair and OR 0.247 for good, P < 0.05) and more sleep (OR 0.642, P < 0.05), were associated with a lower likelihood of depressive symptoms. In contrast, pain (OR 1.440 for mild and OR 2.644 for severe, P < 0.05) and impairment in the basic activities of daily living (OR 1.886, P < 0.05) were inversely associated. Additionally, patients highly satisfied with healthcare services (OR 0.579, P < 0.05) were less likely to have depressive symptoms.

Nearly half of the patients with DM reported depressive symptoms, which were strongly associated with predisposing characteristics and healthcare needs, particularly physical pain and impairment in basic activities of daily living. Our study emphasizes the significance of enhanced screening and intervention for depression in diabetes care along with improved management of functional impairments.

Core Tip: In this cross-sectional analysis, we present the prevalence of and factors associated with depressive symptoms in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM). Nearly half (41%) of the patients with DM reported depressive symptoms, which were strongly associated with predisposing characteristics and healthcare needs, particularly physical pain and impairment in basic activities of daily living. Enhanced screening and interventions for depression in diabetes care, along with improved management of functional impairment, should be implemented.

- Citation: Xiao WH, Yang XC, Xu SJ, Bian Y, Zou GY. Prevalence and associated factors of depressive symptoms in Chinese diabetic patients: A study based on Andersen’s behavioral model. World J Diabetes 2025; 16(4): 100638

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v16/i4/100638.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v16.i4.100638

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a chronic metabolic disease characterized by elevated blood glucose levels. The International Diabetes Federation states that DM is one of the most rapidly growing global health emergencies of the 21st century[1]. As of 2021, approximately 537 million people globally had DM, and this number is expected to rise to 643 million by 2030 and 783 million by 2045[1]. China has over 140 million people living with DM, and DM-related healthcare costs more than $160 billion[1]. Depression is a common mental disorder affecting approximately 300 million people worldwide[2]. It is characterized by persistent sadness and a lack of interest or pleasure in previously rewarding or enjoyable activities[3]. Depression is a major cause of disability in China, ranking fourth in years lived with disability in 2019[4]. According to a large epidemiological survey, the 12-month and lifetime prevalence of depression in the Chinese population is 3.6% and 6.8% respectively[5].

In addition to their individual contributions to the global disease burden, comorbidities of chronic conditions such as DM and depression are common[6-8]. Previous studies have reported a bidirectional relationship between DM and depression[9]. Roy and Lloyd[10] found that individuals with type 2 DM (T2DM) were three times more likely to experience depression than those without T2DM. Campayo et al[11] demonstrated that clinically significant depression was associated with a 65% increased risk of developing DM. According to a meta-analysis by Khaledi et al[12], 28% of patients with T2DM had varying degrees of depressive disorders. Geographically, the prevalence of depression in patients with DM was higher in Asia (32%) and Australia (29%) than in Africa (27%) and Europe (24%). Multiple cross-sectional studies in China have shown that the prevalence of depression among patients with DM ranges from 25.6% to 56.1%[13-15].

The co-occurrence of DM and depression presents a dual burden on healthcare systems and is detrimental to socioeconomic development. Depression in people with DM leads to inadequate self-care, impaired self-management, and decreased quality of life[16-19]. It is also associated with increased healthcare utilization and costs[20-24]. Thus, evaluating the associations between DM and depression and identifying potential risk factors are crucial for early intervention. Researchers in China and abroad have identified several risk factors that increase the risk of depression in people with DM, including low socioeconomic status, adverse life events, health behaviors and status, and DM-related conditions and treatments[10,25-27]. In a community-based study in China, Sun et al[14] found that female sex, older age, lower education, single status, DM complications, and poor sleep quality were associated with an increased risk of depressive symptoms in patients with T2DM. Studies on DM and depression have steadily increased in China. Notably, many of these studies were confined to hospitals or limited geographical regions[28,29]. Moreover, studies utilizing national survey datasets have primarily focused on specific factors associated with depressive symptoms in patients with DM, such as rural-urban structure, physical function, and activities of daily living (ADL)[30,31]. However, systematic analyses of the correlates of depression in patients with DM from a theoretical perspective are rare. In this study, we examined the prevalence of and factors associated with depressive symptoms in Chinese patients with DM, using a nationally representative survey dataset. The analysis was framed within Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Service Use (Andersen’s behavioral model) to comprehensively understand the psychological dimensions of DM management.

In this cross-sectional study, we present the prevalence of and factors associated with depressive symptoms in patients with diabetes. Data were collected from the 2018 China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). CHARLS is a nationally representative survey organized by the National School of Development of Peking University and was conducted by the Institute of Social Science Survey of Peking University. A multi-stage stratified probability proportional to size sampling method was used in the CHARLS to select Chinese residents aged 45 years and older as respondents and collect their social, economic, and health-related information. In 2011, the CHARLS research team conducted a national baseline survey, interviewing 17708 respondents from 28 provinces, 150 countries/districts, and 450 villages/urban communities nationwide. The second, third, and fourth waves of the CHARLS follow-up survey were conducted in 2013, 2015, and 2018, respectively. In 2018, the fourth wave of the CHARLS increased the number of respondents to 19816. More information on the CHARLS, including its design, implementation, data release, and quality control, can be found on the official website (http://charls.pku.edu.cn).

In the present study, our inclusion criteria was a self-reported diagnosis of diabetes in the 2018 CHARLS. The exclusion criteria were: (1) Participants who did not complete the depression scale; and (2) Participants with missing data on predisposing characteristics, enabling resources, healthcare needs, and health behaviors. Ultimately, 1673 participants were eligible to participate in the survey (Supplementary Figure 1).

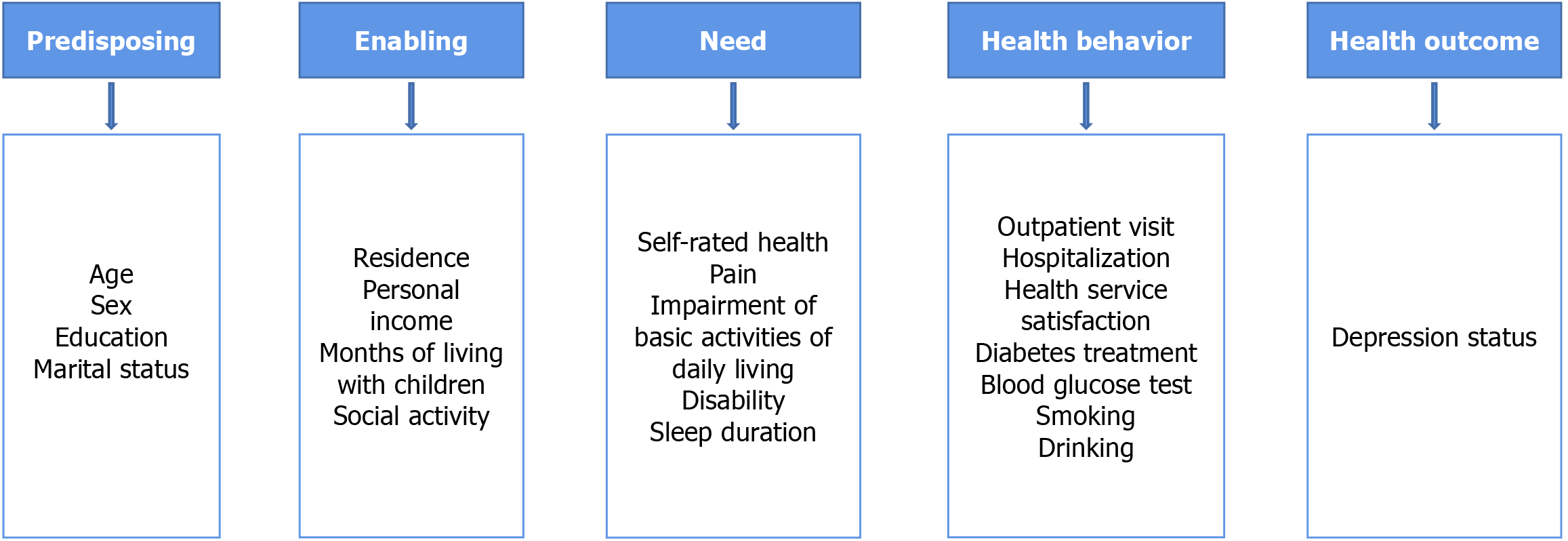

Andersen’s behavioral model, proposed by Andersen[32] in 1968, is a mainstream theoretical model used to study an individual’s health service utilization and behavior. In this model, factors related to individual health behaviors and outcomes are grouped into three categories: Predisposing characteristics, enabling resources, and need[33]. Predisposing factors are characteristics that make individuals more likely to use healthcare services. These factors include demographic characteristics, social structural factors, and health beliefs. However, enabling factors are the resources and abilities that allow individuals to access healthcare services. These factors include financial status, family resources, and social support. The need for healthcare services is influenced by predisposing and enabling factors, including perceived and evaluated needs. Additionally, a correlation exists between individual health behaviors (including health service utilization and lifestyle) and health outcomes. Andersen’s model presents a theoretical framework for a comprehensive understanding of the factors associated with depressive symptoms in patients with DM.

The depression status of patients with DM was the dependent variable. It was assessed using the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CESD-10, Supplementary material). This scale has shown good reliability and validity in middle-aged and older Chinese populations[34]. The CESD-10 comprises 10 questions related to behaviors and feelings. It was designed to determine how frequently the respondent has experienced certain events in the past week. Positive feelings and behaviors that occur less than one day, 1-2 days, 3-4 days, and 5-7 days are scored as 3, 2, 1, and 0 points, respectively. Negative feelings or behaviors follow the opposite pattern. The CESD-10 yields a total score of 30 points. The severity of depressive symptoms is directly proportional to the score. Consistent with previous research[35], individuals scoring 10 or higher were defined as having depressive symptoms.

We examined the potential relationship between depression status in patients with DM and four dimensions: Predisposing characteristics, enabling resources, health needs, and health behaviors using Andersen’s behavioral model. Predisposing characteristics were age, sex, education, and marital status. The enabling resources were the place of residence, personal income in the past year, months of living with children in the past year, and social activities. Healthcare needs were self-rated health, pain, impairment of basic ADL (BADL, assessed using the Basic ADL Scale), disability, and sleep duration. Health behaviors were outpatient visits in the past month, hospitalizations in the past year, satisfaction with healthcare service, DM treatment, blood glucose testing in the past year, and smoking and drinking habits. Figure 1 shows Andersen’s theoretical model of the factors influencing depression in patients with DM.

Data processing and analysis were performed using Stata 16.0 (Stata Corp., LLC.; College Station, TX, United States). Continuous variables are presented as mean and standard deviation, and categorical variables are presented as the number of respondents and sample percentage. Analysis of variance was used for continuous variables, whereas the χ2 test was used for categorical variables to show between-group differences. Binary logistic regression was used to investigate the odds ratios (ORs) of depressive symptoms correlates in patients with DM. The predisposing (Model 1), enabling (Model 2), need (Model 3), and health behavior variables (Model 4) were controlled stepwise to explicitly observe the effect of each factor. The significance level was set at 5%.

Of the 1673 patients with DM, 693 (41.4%) had depressive symptoms. The weighted mean ages of all patients, patients with DM and depressive symptoms, and patients with DM but without depressive symptoms were 63.80, 63.82, and 63.78 years, respectively. More than half of the patients were female (52.1%), had primary or secondary education (64.2%), and were married (87.1%). The proportions of females (67.1% vs 42.3%, P < 0.05), those with no formal education (22.2% vs 11.2%, P < 0.05), and single/divorced/widowed individuals (17.9% vs 9.7%, P < 0.05) were significantly higher in those with depressive symptoms than in patients without depressive symptoms (Table 1).

| Variables | Total | Depressed | Not depressed | P value | ||||||

| n | Unweighted | Weighted | n | Unweighted | Weighted | n | Unweighted | Weighted | ||

| Total | 1673 | 100.0% | 100.0% | 693 | 100.0% | 100.0% | 980 | 100.0% | 100.0% | - |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 1673 | 63.14 ± 8.99 | 63.80 ± 9.28 | 693 | 63.25 ± 9.07 | 63.82 ± 9.30 | 980 | 63.06 ± 8.93 | 63.78 ± 9.27 | 0.936 |

| Sex | < 0.001 | |||||||||

| Female | 914 | 54.6% | 52.1% | 458 | 66.1% | 67.1% | 456 | 46.5% | 42.3% | |

| Male | 759 | 45.4% | 47.9% | 235 | 33.9% | 32.9% | 524 | 53.5% | 57.7% | |

| Education | < 0.001 | |||||||||

| Not formally educated | 310 | 18.5% | 15.5% | 173 | 25.0% | 22.2% | 137 | 14.0% | 11.2% | |

| Primary or middle school | 1083 | 64.7% | 64.2% | 449 | 64.8% | 67.9% | 634 | 64.7% | 61.8% | |

| High school and above | 280 | 16.7% | 20.3% | 71 | 10.2% | 9.9% | 209 | 21.3% | 27.0% | |

| Marital status | < 0.001 | |||||||||

| Single/divorced/widowed | 231 | 13.8% | 12.9% | 131 | 18.9% | 17.9% | 100 | 10.2% | 9.7% | |

| Married/cohabitation | 1442 | 86.2% | 87.1% | 562 | 81.1% | 82.1% | 880 | 89.8% | 90.3% | |

Regarding place of residence, 49.3% of the patients lived in rural areas, and 37.1% lived in urban areas. The weighted median income was ¥5471, and the weighted median number of months of living with children was 3.28 months for all patients. In the past month, 61.6% of the patients had participated in at least one social activity. Individuals with depressive symptoms had a higher proportion of living in rural areas (55.0% vs 45.5%, P < 0.05), a higher proportion of not participating in any social activities (43.8% vs 34.9%, P < 0.05), and a lower personal income (¥1839 vs ¥7835, P < 0.05) than in patients without depressive symptoms. The number of months of living with children was 3.34 and 3.24 months for DM patients with and without depressive symptoms, respectively, and the difference was not statistically significant (Table 2).

| Variables | Total | Depressed | Not depressed | P value | ||||||

| n | Unweighted | Weighted | n | Unweighted | Weighted | n | Unweighted | Weighted | ||

| Total | 1673 | 100.0% | 100.0% | 693 | 100.0% | 100.0% | 980 | 100.0% | 100.0% | - |

| Residence | < 0.001 | |||||||||

| Rural areas | 999 | 59.7% | 49.3% | 460 | 66.4% | 55.0% | 539 | 55.0% | 45.5% | |

| Urban areas | 479 | 28.6% | 37.1% | 150 | 21.6% | 29.7% | 329 | 33.6% | 41.9% | |

| Combination zone | 195 | 11.7% | 13.7% | 83 | 12.0% | 15.3% | 112 | 11.4% | 12.6% | |

| Personal income (mean ± SD) | 1673 | 4881 ± 31882 | 5471 ± 38410 | 693 | 1957 ± 9270 | 1839 ± 9137 | 980 | 6949 ± 40803 | 7835 ± 48663 | 0.003 |

| Months of living with children (mean ± SD) | 1673 | 3.48 ± 6.14 | 3.28 ± 5.75 | 693 | 3.62 ± 6.32 | 3.34 ± 5.87 | 980 | 3.37 ± 6.02 | 3.24 ± 5.68 | 0.735 |

| Social activity | 0.003 | |||||||||

| No | 675 | 40.3% | 38.4% | 317 | 45.7% | 43.8% | 358 | 36.5% | 34.9% | |

| Yes | 998 | 59.7% | 61.6% | 376 | 54.3% | 56.2% | 622 | 63.5% | 65.1% | |

In terms of self-rated health status, 41.0% of patients considered their health to be poor, and only 10.9% considered their health to be good. Body pain was common among patients with DM, with 43.2% having mild pain and 21.3% having severe pain. In addition, 22.6% and 41.4% of patients had BADL impairment and disability, respectively. The weighted mean sleep duration was 6.10 hours. Patients with depressive symptoms were more likely to have a poor self-rated health status (60.8% vs 28.2%, P < 0.05), severe pain (36.3% vs 11.6%, P < 0.05), BADL impairment (36.1% vs 13.8%, P < 0.05), disability (51.5% vs 34.7%, P < 0.05), and fewer hours of sleep (5.65 vs 6.39%, P < 0.05) than in those without depressive symptoms (Table 3).

| Variables | Total | Depressed | Not depressed | P value | ||||||

| N | Unweighted | Weighted | n | Unweighted | Weighted | n | Unweighted | Weighted | ||

| Total | 1673 | 100.0% | 100.0% | 693 | 100.0% | 100.0% | 980 | 100.0% | 100.0% | - |

| Self-rated health | < 0.001 | |||||||||

| Poor | 733 | 43.8% | 41.0% | 445 | 64.2% | 60.8% | 288 | 29.4% | 28.2% | |

| Fair | 753 | 45.0% | 48.1% | 219 | 31.6% | 34.8% | 534 | 54.5% | 56.7% | |

| Good | 187 | 11.2% | 10.9% | 29 | 4.2% | 4.4% | 158 | 16.1% | 15.1% | |

| Pain | < 0.001 | |||||||||

| None | 540 | 32.3% | 35.5% | 130 | 18.8% | 20.2% | 410 | 41.8% | 45.4% | |

| Mild | 721 | 43.1% | 43.2% | 292 | 42.1% | 43.5% | 429 | 43.8% | 43.0% | |

| Severe | 412 | 24.6% | 21.3% | 271 | 39.1% | 36.3% | 141 | 14.4% | 11.6% | |

| BADL impairment | < 0.001 | |||||||||

| No | 1250 | 74.7% | 77.4% | 421 | 60.8% | 63.9% | 829 | 84.6% | 86.2% | |

| Yes | 423 | 25.3% | 22.6% | 272 | 39.2% | 36.1% | 151 | 15.4% | 13.8% | |

| Disability | < 0.001 | |||||||||

| No | 940 | 56.2% | 58.6% | 312 | 45.0% | 48.5% | 628 | 64.1% | 65.3% | |

| Yes | 733 | 43.8% | 41.4% | 381 | 55.0% | 51.5% | 352 | 35.9% | 34.7% | |

| Sleep duration (mean ± SD) | 1673 | 6.06 ± 1.99 | 6.10 ± 1.90 | 693 | 5.59 ± 2.16 | 5.65 ± 2.07 | 980 | 6.39 ± 1.78 | 6.39 ± 1.72 | < 0.001 |

The weighted median number of outpatient visits and hospitalizations was 0.58 and 0.5, respectively, and nearly one-fifth (19.8%) of the patients were dissatisfied with healthcare services. The majority (82.0%) of patients were receiving treatment for DM, and the median number of blood glucose tests was 25.2. Regarding smoking and drinking, 58.4% and 68.3% of patients did not smoke or drink alcohol, respectively. Patients with depressive symptoms had more outpatient visits (0.77 vs 0.46, P < 0.05) and hospitalizations (0.65 vs 0.41, P < 0.05), whereas the proportion of satisfaction with healthcare services (29.0% vs 38.9%, P < 0.05), smoking (33.1% vs 47.2%, P < 0.05), and drinking (24.8% vs 36.2%, P < 0.05) was lower than in patients without depressive symptoms. The proportion of DM treatment (82.5% vs 81.7%, P > 0.05) and blood glucose testing times (24.9 vs 25.4, P < 0.05) were not significantly different between patients with and without DM (Table 4).

| Variables | Total | Depressed | Not depressed | P value | ||||||

| n | Unweighted | Weighted | n | Unweighted | Weighted | n | Unweighted | Weighted | ||

| Total | 1673 | 100.0% | 100.0% | 693 | 100.0% | 100.0% | 980 | 100.0% | 100.0% | - |

| Outpatient visit (mean ± SD) | 1673 | 0.57 ± 1.63 | 0.58 ± 1.54 | 693 | 0.77 ± 2.08 | 0.77 ± 1.96 | 980 | 0.44 ± 1.19 | 0.46 ± 1.18 | < 0.001 |

| Hospitalization (mean ± SD) | 1673 | 0.50 ± 1.11 | 0.50 ± 1.06 | 693 | 0.66 ± 1.39 | 0.65 ± 1.30 | 980 | 0.39 ± 0.83 | 0.41 ± 0.86 | < 0.001 |

| Health service satisfaction | 0.002 | |||||||||

| Dissatisfied | 321 | 19.2% | 19.4% | 159 | 22.9% | 24.1% | 162 | 16.5% | 16.3% | |

| Neutral | 744 | 44.5% | 45.6% | 308 | 44.4% | 46.9% | 436 | 44.5% | 44.8% | |

| Satisfied | 608 | 36.3% | 35.0% | 226 | 32.6% | 29.0% | 382 | 39.0% | 38.9% | |

| DM treatment | 0.724 | |||||||||

| No | 341 | 20.4% | 18.0% | 142 | 20.5% | 17.5% | 199 | 20.3% | 18.3% | |

| Yes | 1332 | 79.6% | 82.0% | 551 | 79.5% | 82.5% | 781 | 79.7% | 81.7% | |

| Blood glucose test (mean ± SD) | 1673 | 20.2 ± 60.0 | 25.2 ± 69.8 | 693 | 22.7 ± 76.4 | 24.9 ± 79.5 | 980 | 18.4 ± 44.9 | 25.4 ± 62.7 | 0.885 |

| Smoking | < 0.001 | |||||||||

| No | 999 | 59.7% | 58.4% | 457 | 65.9% | 66.9% | 542 | 55.3% | 52.8% | |

| Yes | 674 | 40.3% | 41.6% | 236 | 34.1% | 33.1% | 438 | 44.7% | 47.2% | |

| Drinking | < 0.001 | |||||||||

| No | 1186 | 70.9% | 68.3% | 534 | 77.1% | 75.2% | 652 | 66.5% | 63.8% | |

| Yes | 487 | 29.1% | 31.7% | 159 | 22.9% | 24.8% | 328 | 33.5% | 36.2% | |

Binary logistic regression analysis of depression status is shown in Table 5. Model 1 was controlled for predisposing variables and showed that age, sex, and education were significantly correlated with depression status in patients with DM. Notably, marital status was no longer significant in the multivariable analysis. Model 2 examined predisposing and enabling variables. The results showed that a patient’s place of residence and participation in social activities were significantly associated with depression. Model 3 introduced predisposing, enabling, and healthcare need factors and showed that self-rated health, pain, BADL, and sleep duration were significantly associated with depression. However, the variables, including place of residence and participation in social activities, were no longer significant in Model 3.

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||

| OR | SE | OR | SE | OR | SE | OR | SE | |

| Predisposing characteristic | ||||||||

| Age | 0.985a | 0.006 | 0.984a | 0.006 | 0.976b | 0.008 | 0.984 | 0.009 |

| Sex: Male | 0.447b | 0.051 | 0.436b | 0.051 | 0.522b | 0.069 | 0.426b | 0.106 |

| Education1 | ||||||||

| Primary or middle | 0.830 | 0.128 | 0.912 | 0.138 | 0.980 | 0.183 | 0.929 | 0.219 |

| High school and above | 0.335b | 0.070 | 0.416b | 0.087 | 0.459b | 0.112 | 0.432a | 0.141 |

| Marital status: Married | 0.954 | 0.147 | 0.883 | 0.143 | 0.860 | 0.151 | 0.634a | 0.136 |

| Enabling resource | ||||||||

| Residence2 | ||||||||

| Urban areas | - | - | 0.673a | 0.114 | 0.877 | 0.155 | 1.004 | 0.191 |

| Combination zone | - | - | 1.128 | 0.241 | 1.268 | 0.233 | 1.536 | 0.361 |

| Personal income | - | - | 0.986 | 0.020 | 1.006 | 0.024 | 1.020 | 0.024 |

| Months of living with children | - | - | 0.977 | 0.025 | 0.966 | 0.028 | 1.002 | 0.034 |

| Social activity: Yes | - | - | 0.814a | 0.083 | 0.920 | 0.108 | 0.846 | 0.121 |

| Healthcare need | ||||||||

| Self-rated health3 | ||||||||

| Fair | - | - | - | - | 0.475b | 0.063 | 0.458b | 0.074 |

| Good | - | - | - | - | 0.379b | 0.109 | 0.247b | 0.070 |

| Pain4 | ||||||||

| Mild | - | - | - | - | 1.204 | 0.206 | 1.440a | 0.249 |

| Severe | - | - | - | - | 2.372b | 0.424 | 2.644b | 0.532 |

| BADL impairment: Yes | - | - | - | - | 2.112b | 0.270 | 1.886b | 0.323 |

| Disability: Yes | - | - | - | - | 1.267 | 0.158 | 1.332 | 0.201 |

| Sleep duration | - | - | - | - | 0.676b | 0.101 | 0.642a | 0.118 |

| Health behaviors | ||||||||

| Outpatient visit | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.081 | 0.050 |

| Hospitalization | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.006 | 0.063 |

| Health service satisfaction5 | ||||||||

| Neutral | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.902 | 0.174 |

| Satisfied | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.579b | 0.121 |

| DM treatment: Yes | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.912 | 0.162 |

| Blood glucose test | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.005 | 0.053 |

| Smoking: Yes | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.200 | 0.258 |

| Drinking: Yes | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.255 | 0.252 |

Model 4 revealed that satisfaction with healthcare services was significantly associated with depression. Specifically, patients who were more satisfied with healthcare services (OR 0.579, P < 0.05) were less likely to have depressive symptoms. Model 4 also indicated that patients who were male (OR 0.426, P < 0.05), had a high school education or higher (OR 0.432, P < 0.05), and were married (OR 0.634, P < 0.05) were less likely to report depressive symptoms. Better self-rated health status (OR 0.458 for fair and OR 0.247 for good, P < 0.05) and longer sleep duration (OR 0.642, P < 0.05) decreased the probability of depressive symptoms in patients with DM, whereas body pain (OR 1.440 for mild and OR 2.644 for severe, P < 0.05) and impaired BADL (OR 1.886, P < 0.05; OR 1.332, P < 0.05) increased this probability (Table 5).

About 41% of the patients with DM reported depressive symptoms. Depressive symptoms were significantly associated with predisposing characteristics and healthcare needs. Among these factors, physical pain and limitations in BADL were strongly associated with depression.

We found a 41% prevalence of depressive symptoms among patients with DM. This figure is consistent with previous studies in China[15,36] but higher than those reported in Brazil (22%) and the United States (25%)[37,38]. Differences in social and cultural contexts, as well as in the accessibility of mental health services in different countries, could have contributed to this phenomenon. Additionally, differences in the depression scales used in these studies may also explain the differences in prevalence. Despite the high prevalence of depressive symptoms in patients with DM, depression remains underdiagnosed and undertreated in China. According to a meta-analysis, the treatment rate for major depressive disorders in China is only 19.5%[39], suggesting a need to improve depression screening and mental healthcare accessibility.

Predisposing characteristics, including sex, education, and marital status, were significantly associated with depressive symptoms in Model 4. We found that male patients were less likely to have depressive symptoms than female patients were, consistent with previous research identifying female sex as a risk factor for depression in individuals with DM[10,14,25,29]. Patients who were highly educated and married were found to have a lower likelihood of reporting depressive symptoms in this study, which is consistent with previous studies[14,40]. Individuals with lower levels of education or without a spouse may have limited access to health care services, a lack of family care, or an unhealthy lifestyle, contributing to poor health outcomes. Therefore, these patients may be more vulnerable to depressive symptoms. Models 1-3 showed a decreased likelihood of older patients having depressive symptoms, except in Model 4. Bai et al[41] reported a similar relationship. Their study showed that the prevalence of depression was lower in the age groups of 60-74 and ≥ 75 years than in those aged 45-59. This may be because those aged 45-59 years have higher expectations and face increased life and work stress levels. However, some studies have also suggested an increased likelihood of older patients with depressive symptoms, which is inconsistent with our findings[14,37]. This difference may be attributed to the specific demographic focus of the present study, which included only patients with DM aged 45 years or older. Further studies are required to understand these issues thoroughly.

Regarding enabling resources, Model 2 showed a significant correlation between the place of residence, social activities, and depressive symptoms. However, this association was no longer significant in Models 3 and 4. This suggests that some of the variables included in Models 3 and 4 may be covariates of these two factors.

Healthcare needs, including self-rated health, physical pain, BADL, and sleep duration, were associated with depressive symptoms in Model 4. Self-rated health is an individual’s perception of their health and has been recognized as a reflection of the actual state of health. It has also been suggested as a predictor of the onset of mental disorders[42]. In the present study, patients with better self-rated health status were less likely to report depressive symptoms. This is consistent with previous studies showing a negative association between self-rated health and depression[43-45]. Greater healthcare needs, including severe pain and impaired BADL, were associated with an increased risk of depressive symptoms in patients with DM, consistent with previous studies[46,47]. This is because the burden of greater body mass in patients with DM increases pain, leading to higher depression levels. Moreover, DM-related medical problems increase functional impairment, which also leads to higher depression levels[46]. We also found that the associations between severe pain, impaired BADL, and depressive symptoms were particularly robust. This suggests that longer sleep duration may act as a protective factor against depression in patients with DM. However, a U-shaped relationship between sleep duration and depressive symptoms has been reported in previous studies[48,49]. Therefore, healthcare professionals and community workers should pay attention to health status, pain, BADL, and sleep quality assessments when managing patients with DM, to reduce the likelihood of depressive symptoms.

This study revealed a significant association between satisfaction with healthcare services and depression. Patients with DM who reported higher levels of satisfaction with healthcare services were less likely to report depressive symptoms. Depressive symptoms may increase uncertainty about DM treatment, which can negatively impact patients' perceived service quality and lead to decreased overall satisfaction with medical services. Previous studies in different contexts have shown that depression is associated with increased healthcare utilization[20-22,24]. However, the present study did not report a similar association between depression and the number of outpatient visits or hospitalizations. Several reasons likely exist for this discrepancy, and further research is needed to examine the impact of depression on healthcare utilization among individuals with DM in China.

Our study, with its large sample size and theoretical approach, provides a useful foundation for formulating strategies in research and clinical practice to prevent, control, and intervene regarding depression among individuals with diabetes. However, our study has several limitations. First, although data were obtained from CHARLS, a large nationally representative sample survey, the results of this study should be interpreted with caution. CHARLS surveyed community-dwelling individuals aged 45 years and older and did not specifically target individuals with DM or depressive symptoms. In addition, the survey included only middle-aged and older Chinese residents, which might have limited the generalizability of the findings to younger patients with diabetes. Second, the depression scale used in this study was the CESD-10, which applies to the assessment of individual depressive symptoms but cannot diagnose depression clinically. This might have slightly overestimated the prevalence of depression in patients with DM. Third, the development of depression may be influenced by clinical factors related to diabetes, such as duration and severity. However, the present analysis did not include these factors because the CHARLS dataset lacks clinical information on diabetes. Given the limitations of the available data, we acknowledge the importance of these issues and emphasize that caution should be exercised when interpreting our findings.

We found that nearly half of individuals with diabetes reported depressive symptoms, which were strongly associated with predisposing characteristics and healthcare needs, particularly physical pain and impairment of daily activities. Our study emphasizes the significance of enhanced screening and interventions for depression in diabetes care, along with improved management of functional impairments.

The authors appreciate the CHARLS and the field team and every respondent in the survey for their contributions.

| 1. | Magliano DJ, Boyko EJ; IDF Diabetes Atlas 10th edition scientific committee. IDF Diabetes Atlas [Internet]. 10th ed. Brussels: International Diabetes Federation, 2021. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx). 2021. [cited 9 January 2025]. Available from: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool?params=gbd-api-2019-permalink/d780dffbe8a381b25e1416884959e88b. |

| 3. | World Health Organization. Depression. 2022. [cited 9 January 2025]. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/depression#tab=tab_1. |

| 4. | Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Burden of Disease 2019. [cited 9 January 2025]. Available from: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/. |

| 5. | Huang Y, Wang Y, Wang H, Liu Z, Yu X, Yan J, Yu Y, Kou C, Xu X, Lu J, Wang Z, He S, Xu Y, He Y, Li T, Guo W, Tian H, Xu G, Xu X, Ma Y, Wang L, Wang L, Yan Y, Wang B, Xiao S, Zhou L, Li L, Tan L, Zhang T, Ma C, Li Q, Ding H, Geng H, Jia F, Shi J, Wang S, Zhang N, Du X, Du X, Wu Y. Prevalence of mental disorders in China: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:211-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1590] [Cited by in RCA: 1355] [Article Influence: 225.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Abegunde DO, Mathers CD, Adam T, Ortegon M, Strong K. The burden and costs of chronic diseases in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2007;370:1929-1938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 834] [Cited by in RCA: 842] [Article Influence: 46.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jiang CH, Zhu F, Qin TT. Relationships between Chronic Diseases and Depression among Middle-aged and Elderly People in China: A Prospective Study from CHARLS. Curr Med Sci. 2020;40:858-870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1069-1078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2579] [Cited by in RCA: 2561] [Article Influence: 106.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Golden SH. A review of the evidence for a neuroendocrine link between stress, depression and diabetes mellitus. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2007;3:252-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Roy T, Lloyd CE. Epidemiology of depression and diabetes: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2012;142 Suppl:S8-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 881] [Cited by in RCA: 769] [Article Influence: 59.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Campayo A, de Jonge P, Roy JF, Saz P, de la Cámara C, Quintanilla MA, Marcos G, Santabárbara J, Lobo A; ZARADEMP Project. Depressive disorder and incident diabetes mellitus: the effect of characteristics of depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:580-588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Khaledi M, Haghighatdoost F, Feizi A, Aminorroaya A. The prevalence of comorbid depression in patients with type 2 diabetes: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis on huge number of observational studies. Acta Diabetol. 2019;56:631-650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 33.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Li Z, Guo X, Jiang H, Sun G, Sun Y, Abraham MR. Diagnosed but Not Undiagnosed Diabetes Is Associated with Depression in Rural Areas. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13:1136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sun N, Lou P, Shang Y, Zhang P, Wang J, Chang G, Shi C. Prevalence and determinants of depressive and anxiety symptoms in adults with type 2 diabetes in China: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e012540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Liu H, Xu X, Hall JJ, Wu X, Zhang M. Differences in depression between unknown diabetes and known diabetes: results from China health and retirement longitudinal study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2016;28:1191-1199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, Tandon A, Patel V, Ustun B. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet. 2007;370:851-858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2533] [Cited by in RCA: 2614] [Article Influence: 145.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | de Groot M, Anderson R, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. Association of depression and diabetes complications: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:619-630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1157] [Cited by in RCA: 1132] [Article Influence: 47.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Holt RI, Katon WJ. Dialogue on Diabetes and Depression: Dealing with the double burden of co-morbidity. J Affect Disord. 2012;142 Suppl:S1-S3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Suzuki T, Shiga T, Kuwahara K, Kobayashi S, Suzuki S, Nishimura K, Suzuki A, Ejima K, Manaka T, Shoda M, Ishigooka J, Kasanuki H, Hagiwara N. Prevalence and persistence of depression in patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillator: a 2-year longitudinal study. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2010;33:1455-1461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Vamos EP, Mucsi I, Keszei A, Kopp MS, Novak M. Comorbid depression is associated with increased healthcare utilization and lost productivity in persons with diabetes: a large nationally representative Hungarian population survey. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:501-507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Subramaniam M, Sum CF, Pek E, Stahl D, Verma S, Liow PH, Chua HC, Abdin E, Chong SA. Comorbid depression and increased health care utilisation in individuals with diabetes. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31:220-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kyung Lee H, Hee Lee S. Depression, Diabetes, and Healthcare Utilization: Results from the Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging (KLoSA). Iran J Public Health. 2014;43:6-15. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Egede LE, Walker RJ, Bishu K, Dismuke CE. Trends in Costs of Depression in Adults with Diabetes in the United States: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2004-2011. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:615-622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Brüne M, Linnenkamp U, Andrich S, Jaffan-Kolb L, Claessen H, Dintsios CM, Schmitz-Losem I, Kruse J, Chernyak N, Hiligsmann M, Hermanns N, Icks A. Health Care Use and Costs in Individuals With Diabetes With and Without Comorbid Depression in Germany: Results of the Cross-sectional DiaDec Study. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:407-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Fisher EB, Chan JC, Nan H, Sartorius N, Oldenburg B. Co-occurrence of diabetes and depression: conceptual considerations for an emerging global health challenge. J Affect Disord. 2012;142 Suppl:S56-S66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sartorius N. Depression and diabetes. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2018;20:47-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Sun JC, Xu M, Lu JL, Bi YF, Mu YM, Zhao JJ, Liu C, Chen LL, Shi LX, Li Q, Yang T, Yan L, Wan Q, Wu SL, Liu Y, Wang GX, Luo ZJ, Tang XL, Chen G, Huo YN, Gao ZN, Su Q, Ye Z, Wang YM, Qin GJ, Deng HC, Yu XF, Shen FX, Chen L, Zhao LB, Wang TG, Lai SH, Li DH, Wang WQ, Ning G; Risk Evaluation of Cancers in Chinese Diabetic Individuals: A Longitudinal (REACTION) Study group. Associations of depression with impaired glucose regulation, newly diagnosed diabetes and previously diagnosed diabetes in Chinese adults. Diabet Med. 2015;32:935-943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chen F, Wei G, Wang Y, Liu T, Huang T, Wei Q, Ma G, Wang D. Risk factors for depression in elderly diabetic patients and the effect of metformin on the condition. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1063. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Yu S, Yang H, Guo X, Zheng L, Sun Y. Prevalence of Depression among Rural Residents with Diabetes Mellitus: A Cross-Sectional Study from Northeast China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13:542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Liu H, Fan X, Luo H, Zhou Z, Shen C, Hu N, Zhai X. Comparison of Depressive Symptoms and Its Influencing Factors among the Elderly in Urban and Rural Areas: Evidence from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:3886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Yan Y, Du Y, Li X, Ping W, Chang Y. Physical function, ADL, and depressive symptoms in Chinese elderly: Evidence from the CHARLS. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1017689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Andersen RM. A Behavioral Model of Families' Use of Health Services. Chicago: Center for Health Administration Studies, University of Chicago, 1968. |

| 33. | Andersen R, Newman JF. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc. 1973;51:95-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2028] [Cited by in RCA: 1852] [Article Influence: 35.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Chen H, Mui AC. Factorial validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale short form in older population in China. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26:49-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 334] [Cited by in RCA: 380] [Article Influence: 34.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Boey KW. Cross-validation of a short form of the CES-D in Chinese elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999;14:608-617. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 36. | Liu Y, Maier M, Hao Y, Chen Y, Qin Y, Huo R. Factors related to quality of life for patients with type 2 diabetes with or without depressive symptoms - results from a community-based study in China. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22:80-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Briganti CP, Silva MT, Almeida JV, Bergamaschi CC. Association between diabetes mellitus and depressive symptoms in the Brazilian population. Rev Saude Publica. 2018;53:05. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Wang Y, Lopez JM, Bolge SC, Zhu VJ, Stang PE. Depression among people with type 2 diabetes mellitus, US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 2005-2012. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Qi H, Zong QQ, Lok GKI, Rao WW, An FR, Ungvari GS, Balbuena L, Zhang QE, Xiang YT. Treatment Rate for Major Depressive Disorder in China: a Meta-Analysis of Epidemiological Studies. Psychiatr Q. 2019;90:883-895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Jeong M. Factors Associated with Depressive Symptoms in Korean Adults with Diabetes Mellitus: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9:1049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Bai S, Wang J, Liu J, Miao Y, Zhang A, Zhang Z. Analysis of depression incidence and influence factors among middle-aged and elderly diabetic patients in China: based on CHARLS data. BMC Psychiatry. 2024;24:146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Chang-Quan H, Xue-Mei Z, Bi-Rong D, Zhen-Chan L, Ji-Rong Y, Qing-Xiu L. Health status and risk for depression among the elderly: a meta-analysis of published literature. Age Ageing. 2010;39:23-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Rantanen AT, Korkeila JJA, Kautiainen H, Korhonen PE. Poor or fair self-rated health is associated with depressive symptoms and impaired perceived physical health: A cross-sectional study in a primary care population at risk for type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Eur J Gen Pract. 2019;25:143-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Badawi G, Gariépy G, Pagé V, Schmitz N. Indicators of self-rated health in the Canadian population with diabetes. Diabet Med. 2012;29:1021-1028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Guo H, Wang X, Mao T, Li X, Wu M, Chen J. How psychosocial outcomes impact on the self-reported health status in type 2 diabetes patients: Findings from the Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes and Needs (DAWN) study in eastern China. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0190484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Sacco WP, Bykowski CA, Mayhew LL. Pain and functional impairment as mediators of the link between medical symptoms and depression in type 2 diabetes. Int J Behav Med. 2013;20:22-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Egede LE. Diabetes, major depression, and functional disability among U.S. adults. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:421-428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Stamatakis KA, Punjabi NM. Long sleep duration: a risk to health or a marker of risk? Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11:337-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Kripke DF, Brunner R, Freeman R, Hendrix SL, Jackson RD, Masaki K, Carter RA. Sleep Complaints of Postmenopausal Women. Clin J Womens Health. 2001;1:244-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |