Published online Feb 15, 2025. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v16.i2.100801

Revised: October 24, 2024

Accepted: November 21, 2024

Published online: February 15, 2025

Processing time: 125 Days and 19.3 Hours

Diabetes mellitus has become one of the major pandemics of the 21st century. In this scenario, nursing interventions are essential for improving self-care and quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nursing interventions are crucial for managing the disease and preventing complications.

To analyse nursing interventions in recent years through a systematic review and meta-analysis and to propose improvements in care plans.

This study conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of nursing interventions on quantitative glycaemic variables, such as glycated haemoglobin and fasting plasma glucose.

After confirming that the combined effect of all studies from the past 5 years positively impacts quantitative variables, a descriptive analysis of the studies with the most significant changes was conducted. Based on this, an improvement in diabetic patient care protocols has been proposed through follow-up plans tailored to the patient’s technological skills.

The combined results obtained and the proposal for improvement developed in this manuscript could help to improve the quality of life of many people around the world.

Core Tip: Diabetes mellitus is a major global health issue, and practical nursing interventions are vital for improving self-care and quality of life for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. This study presented a systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the impact of nursing interventions on glycaemic control, specifically glycated haemoglobin and fasting plasma glucose. The findings confirmed that these interventions significantly improved glycaemic parameters. Based on these insights, the study proposes protocol enhancements, including personalized follow-up plans aligned with patients’ technological abilities, to optimize care and improve outcomes for millions worldwide.

- Citation: Grande-Alonso M, Barbado García M, Cristóbal-Aguado S, Aguado-Henche S, Moreno-Gómez-Toledano R. Improving nursing care protocols for diabetic patients through a systematic review and meta-analysis of recent years. World J Diabetes 2025; 16(2): 100801

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v16/i2/100801.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v16.i2.100801

Diabetes mellitus (DM) has become one of the major public health emergencies of the 21st century, with a steadily increasing global prevalence[1]. In 1980, approximately 108 million adults aged 20 to 79 were affected by this disease. Currently, the global prevalence has risen to 10.5% of the population, affecting 536 million people, and it is projected that by 2045, this figure will increase to 12.2%[1,2]. DM is characterized by an alteration in the regulation of blood glucose levels, which can lead to severe complications if not managed properly[3]. This disease can manifest in various forms, with type 2 DM (T2DM) being the most prevalent and accounting for approximately 90% of cases[4].

T2DM is a chronic disease characterized by hyperglycaemia due to alterations in insulin production or an ineffective use of this hormone, leading to an imbalance in glucose homeostasis and consequently a reduced glucose availability for the cells[3].

Various risk factors contribute to the development of T2DM. Some of them are non-modifiable; however, overweight, sedentary lifestyle, hypertension, harmful habits (such as alcohol and tobacco consumption), diet, and cholesterol levels are modifiable[3]. Due to the long-term impact of T2DM on quality of life and its increasing prevalence, especially in an aging population, it is crucial to implement preventive measures, early diagnosis, and proper management of the disease, thus addressing these modifiable factors.

In this context, nursing interventions are crucial to improving self-care and patient quality of life. Self-care in people with T2DM is essential for the control of this disease and the prevention of complications. Nursing interventions aimed at educating patients on managing their condition, promoting healthy lifestyle habits, and adhering to treatment have proven effective in improving glycaemic control and other risk factors associated with T2DM[5]. Additionally, the personalized care nurses provide, which includes regular monitoring of blood glucose levels, adjusting medication as necessary, and providing emotional support, plays a crucial role in managing T2DM[6,7]. Interventions that focus on patient empowerment, such as glucose self-monitoring and developing health-related decision-making skills, are essential for effective self-care[8,9].

Given the increasing prevalence of T2DM and the evidence supporting the effectiveness of nursing interventions, it is necessary to conduct a systematic review of the various interventions implemented to date. This review aimed to unify existing knowledge and provide a practical guide to improve self-care and the quality of life of the adult population with T2DM. Moreover, this review helped identify gaps in current research and priority areas for future research. This systematic review evaluated the effectiveness of nursing interventions in improving self-care and the quality of life of adult patients with T2DM, providing a comprehensive view of the most effective strategies and their implications for clinical practice. Subsequently, by performing a meta-analysis, the effect of nursing interventions was studied in a combined manner, and the studies with the greatest impact on the patient were identified, with the aim of proposing improvements in the care plans.

The study used the PRISMA guidelines[10,11] as the methodological basis. The main objective was to provide an update on the state of the art in relation to the different nursing interventions in health education focused on improving DM control. For this reason, all original studies that studied possible nursing interventions for glycaemic control were selected.

The search for articles of interest was carried out in July 2024, using the academic reference search engines PubMed (PubMed.ncbi.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, accessed 3 July 2024), Web of Science (webofscience.com/wos/alldb/basicsearch, accessed 3 July 2024), and Google Scholar (https://scholar.google.com.mx/scholar, accessed 3 July 2024). A strategy focusing on generic terms was used to maximize results to include potential articles of interest. The terms ((((“Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus” OR T2DM OR “Type 2 Diabetes”) AND (Nursing intervention)) AND (“Therapeutic Education” or “Health Promotion” or “Health Education”)) AND (Hb1Ac OR fasting blood glucose OR glucose OR glycated hae

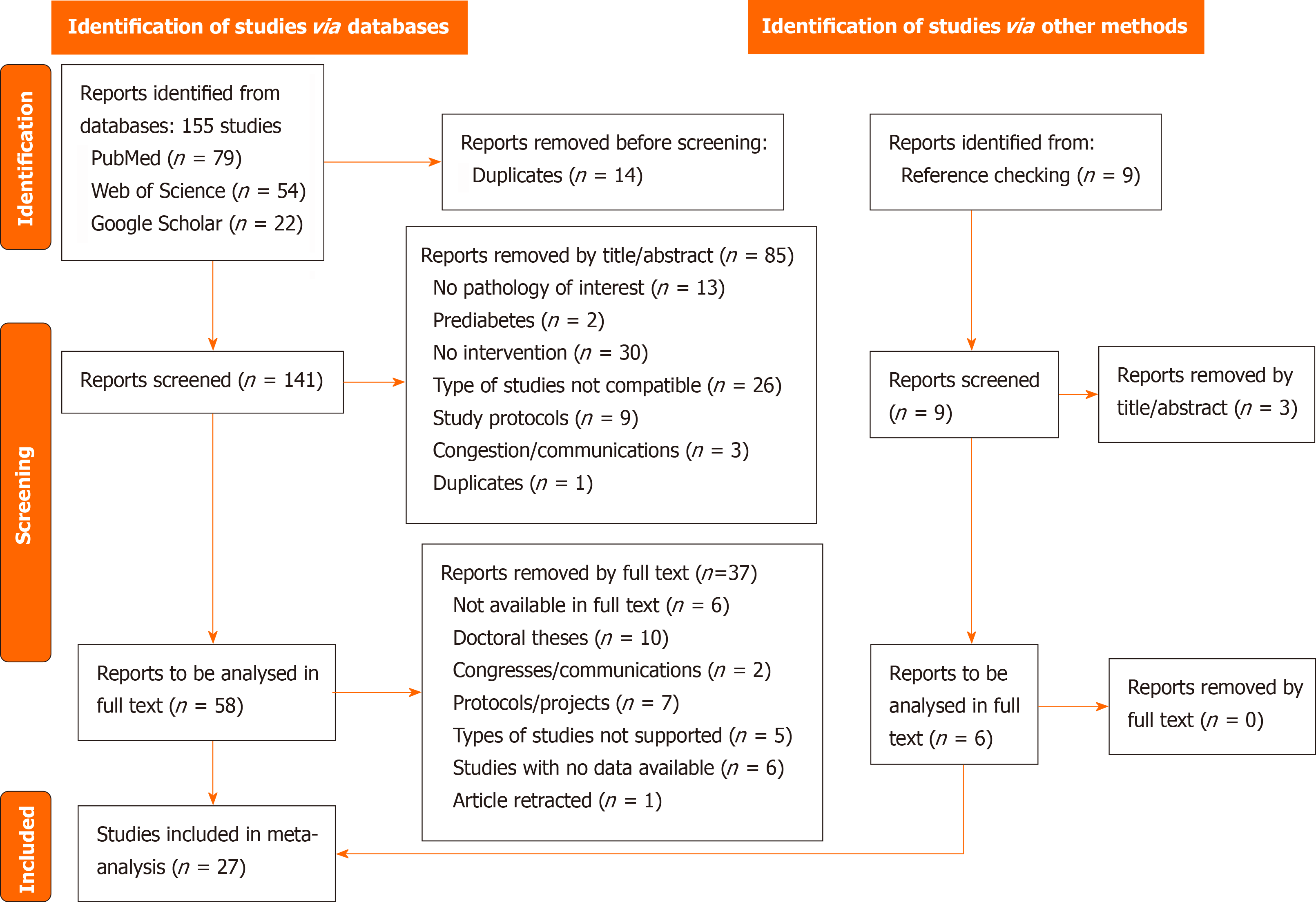

After removing duplicate articles using the bibliographic manager Mendeley (Mendeley Ltd., Elsevier, London, United Kingdom), articles were evaluated by title/abstract. All articles that were not original intervention studies (such as observational studies) or reviews, articles that did not study the pathology of interest, protocols, or conference abstracts were excluded (Figure 1). Subsequently, the full text of the manuscripts was analysed and evaluated.

After the full-text analysis, a descriptive analysis of the selected articles was carried out. In addition, data were extracted for the qualitative and subsequent quantitative analysis. All studies that provided fasting plasma glucose (FPG) or glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) values were included, both in interventions where the study group was compared with a control group (intergroup) and in those studies where preintervention and postintervention values were selected. Discrepancies between independent reviews were resolved by consensus.

RMGT, MGA, MBG, SAH, and SCA extracted data from all studies and were analysed jointly in the form of a meta-analysis. After obtaining the results, those manuscripts with the highest quantitative improvements in the patient’s pathology were selected and included in Table 1. The variables collected from each article in Table 1 were authorship, year of publication, type of study, intervention groups, follow-up period, sample size, and the quantitative variables related to DM (FPG and/or HbA1c).

| Ref. | Study type and intervention groups | Follow-up period | Sample sizes for demographic data | HbA1c %, GM ± SD | FPG glucose in mg/dL, GM ± SD |

| Kim and Utz[39] | Randomized clinical trial | 12 weeks | Not evaluated | ||

| CG: Usual care | CG (n = 52): Female: 63.5%; Age median: 56 ± 10.0 yr | CG: Pre: 8.73 ± 1.43; Post: 6.74 ± 1.07 | |||

| EG1: DM management intervention based on social networks and health literacy-sensitive patient activation, self-care behaviours, and glucose control | EG1 (n = 52): Female: 40.4%; Age median: 46 ± 15.5 yr | EG1: Pre: 9.55 ± 1.66; Post: 6.98 ± 1.36 | |||

| EG2: DM management intervention based on phone calls | EG2 (n = 51): Female: 54.9%; Age median: 52 ± 17.0 yr | EG2: Pre: 9.05 ± 1.79; Post: 7.40 ± 1.90 | |||

| Chen et al[13] | Randomised clinical trial | 3 months | |||

| CG: Follow-up was conducted through telephone or clinic visits every 2 weeks. Patients received routine health education, dietary instructions, and blood glucose monitoring during follow-up | CG (n = 45): Female: 44.44%; Age median: 45.4 ± 3.2 | CG: Pre: 9.02 ± 1.94 Post: 7.99 ± 2.09 | CG (mmol/L): Pre: 9.01 ± 0.19 Post: 8.01 ± 1.44 | ||

| EG: The EG received interactive health education based on the WeChat platform. An interactive healthcare team (physicians and nurses) was established to support patients via WeChat, providing disease education, daily life guidelines, and personalized consultation. This account sent out 2 messages per week with informative audiovisual material and provided an interactive space for asking questions and interacting with other participants | EG (n = 45): Female: 42.22%; Age median: 46.1 ± 3.1 | EG: Pre: 9.05 ± 2.00; Post: 6.82 ± 1.69 | EG (mmol/L): Pre: 8.94 ± 0.21; Post: 7.03 ± 2.04 | ||

| Moradi et al[15] | Randomised clinical trial | 3 months | |||

| CG: Received only routine training | CG (n = 80): Female: 43%; Age: 47.3 ± 7.9 | CG: Pre: 8.52 ± 1.57; Post: 8.54 ± 1.81 | CG: Pre: 221 ± 102; Post: 216 ± 93 | ||

| EG: Educational intervention via mobile cells on foot care knowledge and foot care practices (daily check feet for cuts, redness, sores, ulcers, and blisters, daily washing and drying feet, using moisturizing creams to protect foot from dryness, using shoes and coverings properly, properly trimming toe nails, not cutting off the edge of toe nails, not tampering with the warts and crests, and visiting physicians regularly) | EG (n = 80): Female: 39%; Age: 48.11 ± 9.7 | EG: Pre: 8.56 ± 1.65; Post: 7.39 ± 1.44 | EG: Pre: 239 ± 96; Post: 180 ± 74 | ||

| Wu et al[17] | Randomised clinical trial | 6 months | |||

| CG: Received general education about T2DM using a conventional teaching mode | CG (n = 46): Female: 52.2%; Age: 61.1 ± 10.0 | CG: Pre: 8.0 ± 0.6 Post: 7.4 ± 0.7 | CG: Pre: 167.6 ± 28.1 Post: 165.0 ± 42.6 | ||

| EG: The EG received educational sessions using Steno Balance Cards, which involves guided group dialogue | EG (n = 46): Female: 54.4%; Age: 62.5 ± 6.1 | EG: Pre: 8.1 ± 0.7; Post: 6.8 ± 0.8 | EG: Pre: 174.9 ± 19.9; Post: 131.2 ± 32.3 | ||

| Qasim et al[22] | Randomised clinical trial | 3 months | Not evaluated | ||

| CG: Routine DM counselling provided by trained DM clinic nurses. Counselling sessions were conducted in groups of 6-8 people, with each session lasting between 30-40 min | CG (n = 61): Female: 44.8%; Age 30-44: 24.1%; Age 45-60: 75.9% | CG: Pre: 10 ± 1.8 Post: 9.1 ± 1.8 | |||

| EG: 4 education sessions each (in groups of 6-8 participants) lasting 40 min each | EG (n = 62): Female: 57.4%; Age 30-44: 25.9%; Age 45-60: 74.1% | EG: Pre: 9.0 ± 1.5; Post: 8.2 ± 1.4 | |||

| Elgerges[37] | Randomised clinical trial | 3 months | |||

| CG: Usual care | CG (n = 50): Female: 44%; Age: 54.30 ± 6.69 | CG: Pre: 7.7 ± 1.8 Post: 7.5 ± 1.5 | CG: Pre: 168.0 ± 61.8 Post: 158.6 ± 52.5 | ||

| EG: Therapeutic education workshop by a multidisciplinary team (doctor, a nurse, a psychologist, and a dietician) The intervention session lasted for a period of 6 h. The topics covered were the sugar journey, definition of DM, types, causes, consequences, treatment, and self-management in terms of medication compliance, self-monitoring of blood glucose, diet, physical activity, foot care, and stress management. The pedagogical methods used were video, concept map, posters, demonstrations, role-plays, and lectures. During the session, healthy snacks were distributed, and a pedometer and educational kit were offered. Every 2 weeks, a phone call was made to the experimental group to check their practices and if they had any questions | EG (n = 50): Female: 56%; Age: 54.58 ± 6.58 | EG: Pre: 8.40 ± 1.52 Post: 6.80 ± 0.70 | EG: Pre: 181.1 ± 60.8; Post: 140.3 ± 29.5 | ||

| Alison and Anselm[36] | Randomised clinical trial | 12 months | Not evaluated | ||

| CG: Received normal clinic visits with consultations by a medical officer | CG (n = 50): Female: 66%; Age: 52.38 ± 11.39 | CG: Pre: 10.04 ± 1.29 Post: 9.56 ± 1.65 | |||

| EG: Received four or more DM Medication Therapy Adherence Clinic visits in addition to normal clinic visits | EG (n = 50): Female: 58%; Age: 52.66 ± 9.35 | EG: Pre: 10.46 ± 1.64 Post: 8.69 ± 1.79 | |||

| Subramanian et al[40] | Randomised clinical trial | 15 days | Not evaluated | ||

| CG: Routine DM counselling provided. The routine care was consultation with the doctor and a follow-up once every 2 weeks to get antidiabetic medications; every 3rd month, a routine blood test was performed | CG (n = 35) | CG: Pre: 160.57 ± 58.7 Post: 161.57 ± 55.86 | |||

| EG: Received nurse-led intervention on video-assisted teaching regarding nature of the disease condition including, diet, medication, hand and leg exercises, and home care management for 30 min. Then a demonstration of hand and leg exercise was done followed by return demonstration by the participants | EG (n = 35) More than 40% were in the age group of > 60 years and > 60.0% were females. No significant disparity between experimental and control groups was observed | EG: Pre: 146.70 ± 54.63; Post: 132.80 ± 42.87 | |||

| Hoyo et al[38] | Randomised clinical trial | 18 months | Not evaluated | ||

| CG: Nurses provided treatment as usual | CG (n = 198): Female: 71%; Age: 71.5 ± 10.5 | CG: Pre: 8.65 ± 1.40 Post: 8.84 ± 1.38 | |||

| EG: Motivational nurse-led proactive monthly intervention by telephone, centred in a psychoeducational personalized monitoring protocol | EG (n = 198): Female: 71.6%; Age: 71.4 ± 10.3 | EG: Pre: 8.72 ± 1.49 Post: 7.03 ± 1.09 |

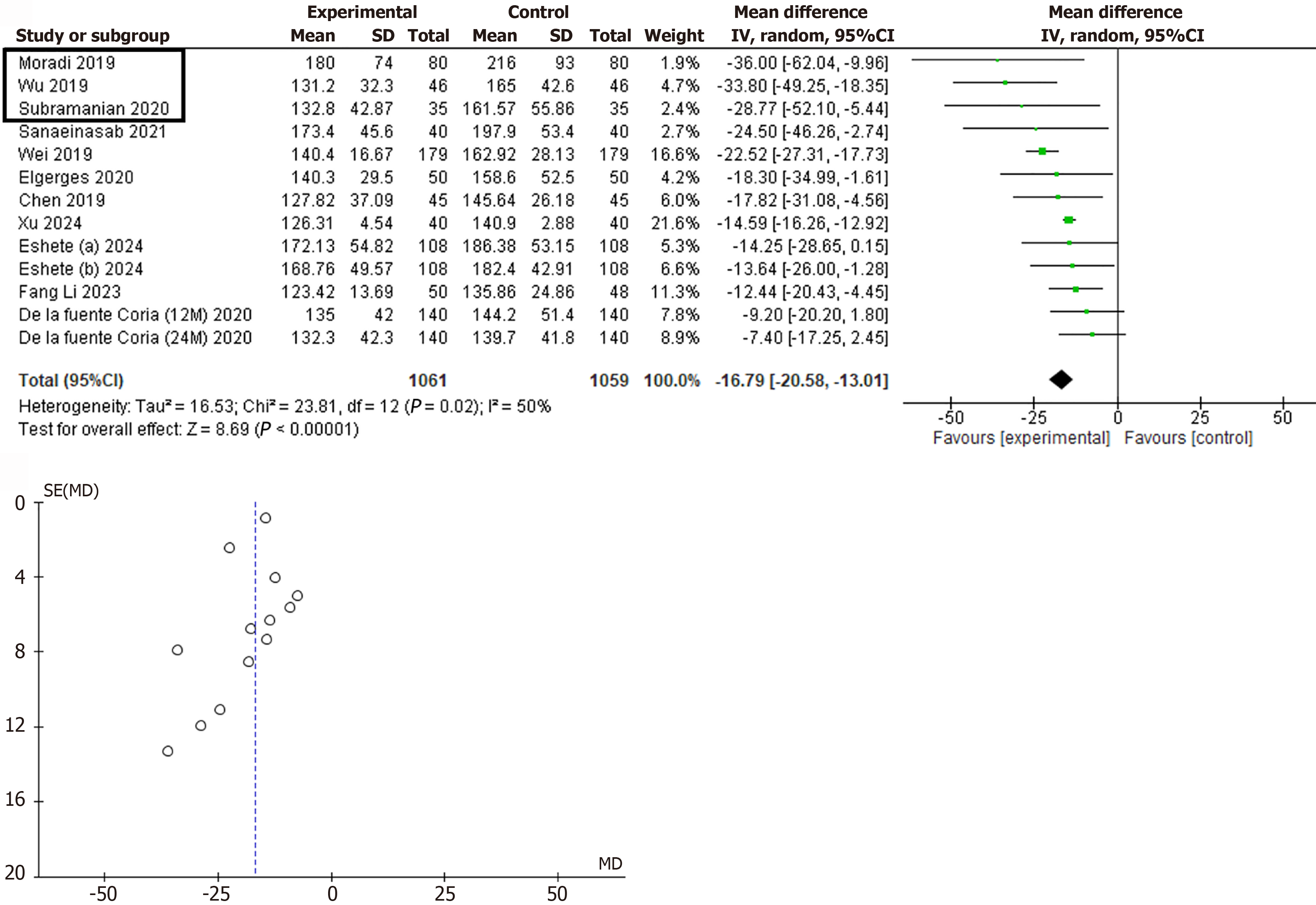

Review Manager software (RevMan 5.3, Cochrane, London, United Kingdom) was used to perform the mean difference method using the variables arithmetic mean, standard deviation, and sample size. Four different meta-analyses were performed: At the intragroup level (control group vs intervention group); FPG; HbA1c; and at the intergroup level (preintervention vs postintervention). Both quantitative glycaemic parameters were also analysed.

Heterogeneity among studies was calculated by applying the χ2 and I2 tests. The I2 statistic was calculated as a percentage, and the results were interpreted as low, medium, or high heterogeneity, reaching 25%, 50% and 75%, respectively[12]. The fixed-effect model was used when no heterogeneity was detected among studies, while the random-effect model was preferred when variance existed. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all the analyses performed.

To evaluate publication bias in the meta-analysis, funnel plots were used to identify symmetry or asymmetry in the distribution of results.

The initial search identified 79 articles in PubMed, 54 in Web of Science, and 22 in Google Scholar. After exporting the reference set to the Mendeley desktop application and removing duplicates, 141 articles were obtained. The first analysis based on the title and abstract eliminated 83 articles that did not meet the selection criteria, resulting in a total of 58 articles. Subsequently, a thorough full-text reading of the remaining articles was performed, leaving a total of 21 studies with interventions to be included in the review. In addition, a manual identification of studies was carried out outside the database search and a total of nine articles were found, of which six were included after applying the selection criteria. Finally, 27 manuscripts meeting the search criteria were selected for qualitative and quantitative analysis[13-40] (Figure 1).

The results have been classified based on the study type and the quantitative variable of blood glucose analysis. Within the study type, they have been categorized as either intragroup (baseline vs post-treatment) or intergroup (control vs intervention). The quantitative variables for blood glucose analysis have been classified as HbA1c and FPG.

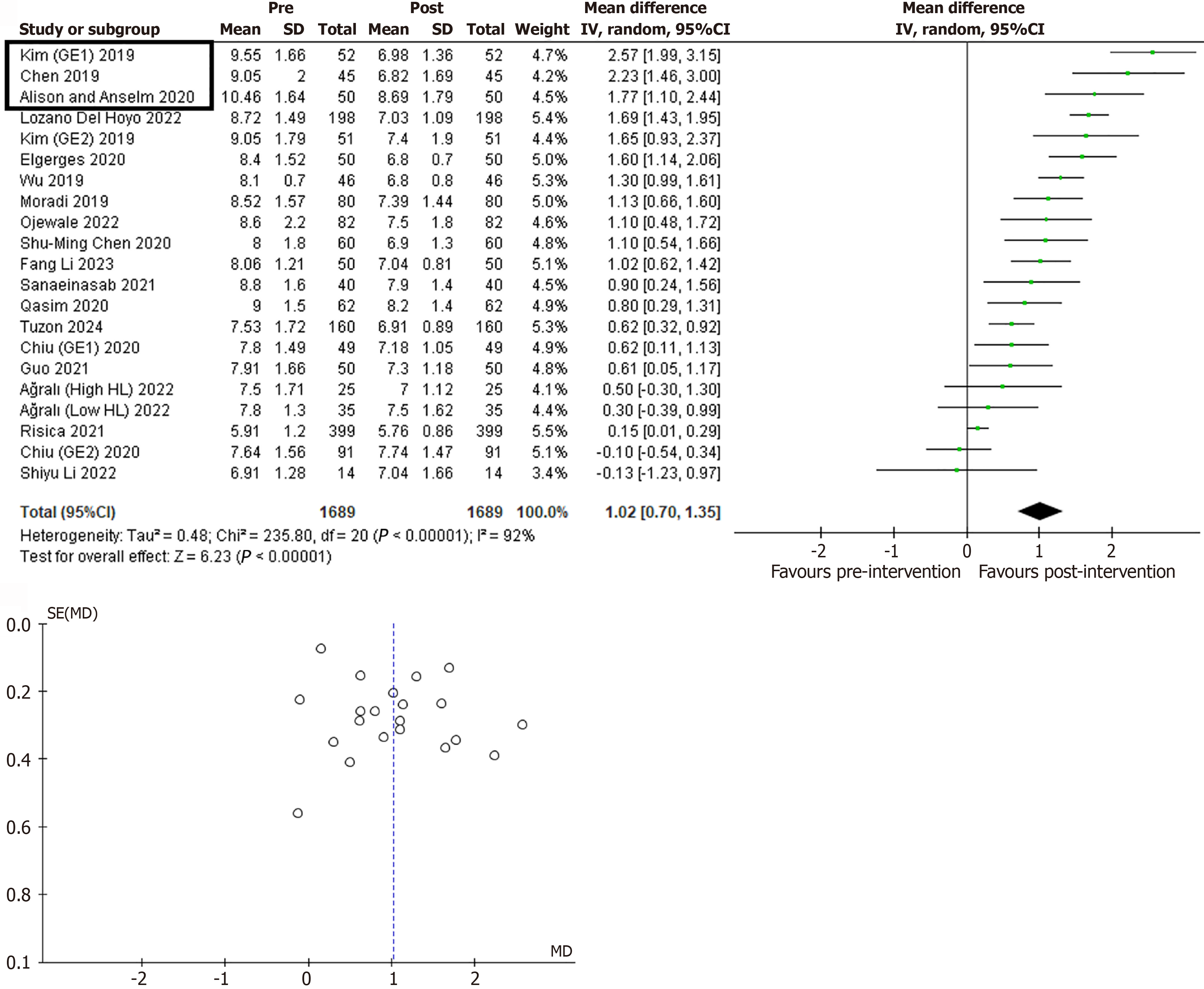

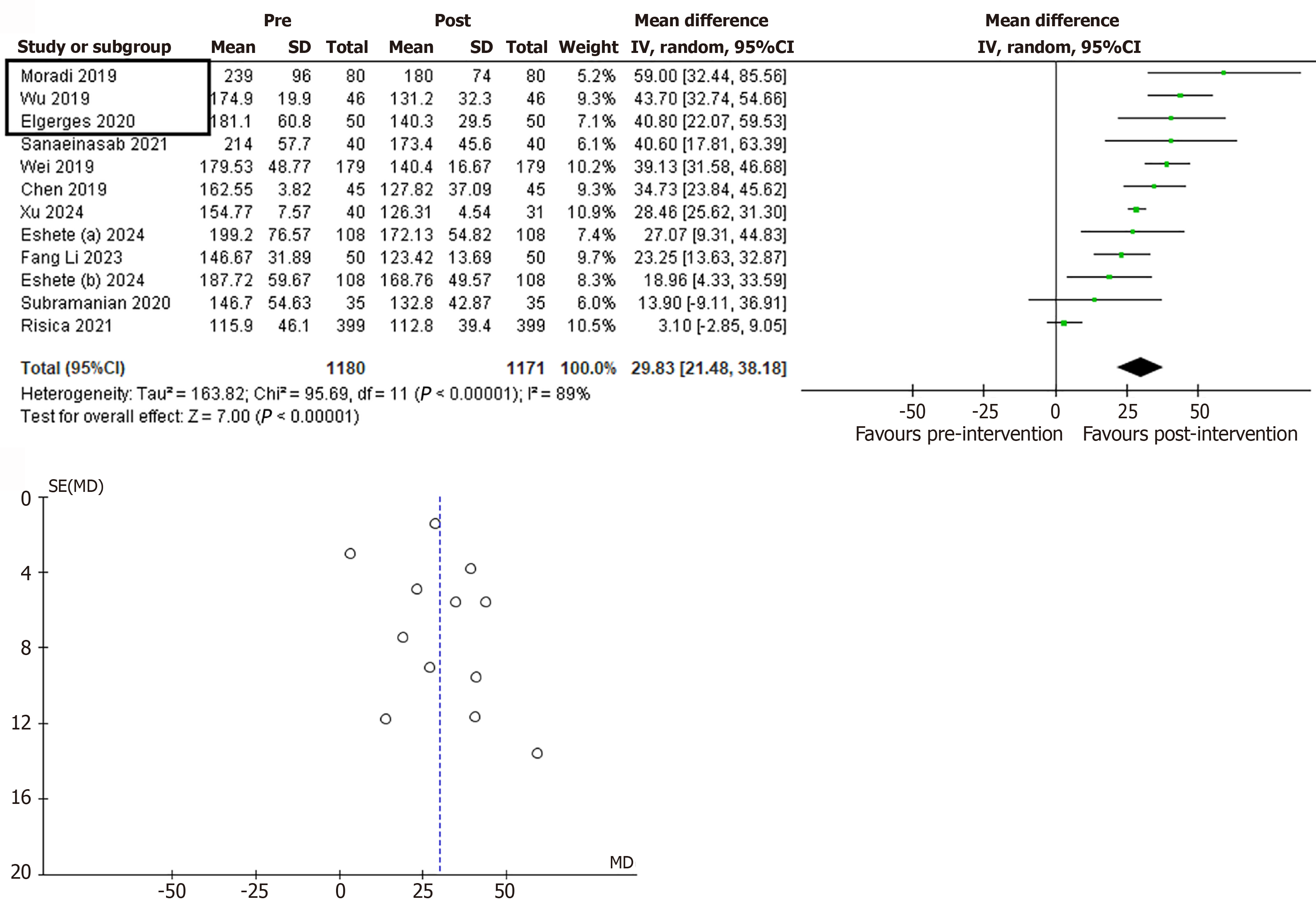

Intragroup differences: As shown in Figures 2 and 3, the results exhibited high heterogeneity, with I² values exceeding 90%. In this case, the figures present striking results, with almost all data shifted to the right side, demonstrating a predominance in favour of postintervention outcomes in both glycaemic parameters. Accordingly, the results of the combined analysis showed a value of 1.03 (0.67, 1.39) (P < 0.00001) for HbA1c and 33.95 (22.70, 45.20) (P < 0.00001) for FPG.

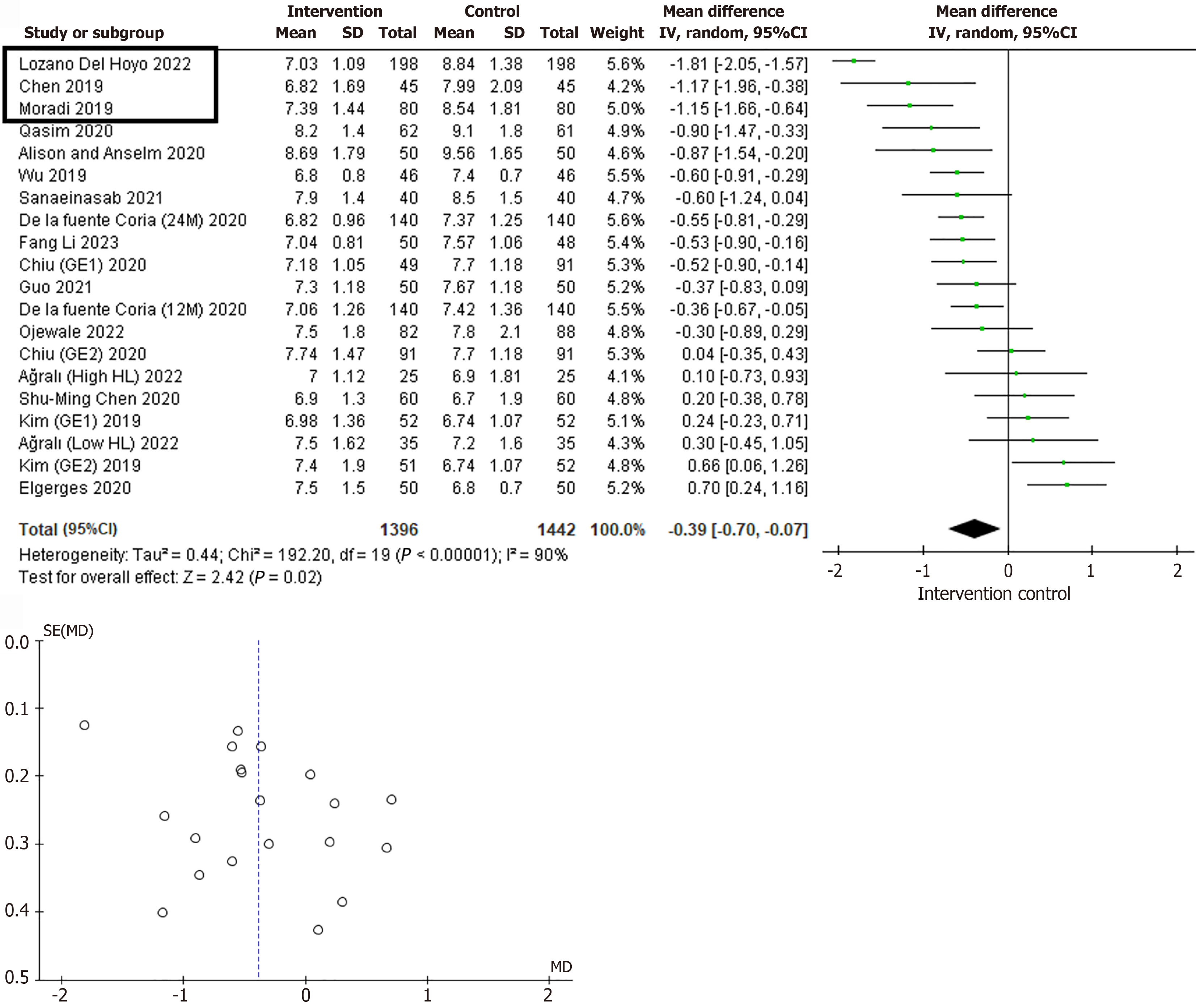

Intergroup differences: As in the previous group, there was a high-to-moderate heterogeneity in health education studies from a nursing perspective over the last 5 years, with I2 values of 90% for HbA1c and 50% for FPG. Notably, the combined results revealed statistically significant data in favour of the intervention supported by a mean difference of -0.27 (-0.49, -0.05) (P < 0.02) for HbA1c and -21.11 (-27.14, -15.07) (P < 0.00001) for FPG.

As can be seen in Figures 2, 3, 4, and 5, the studies included in all the meta-analyses do not have a high degree of dispersion. Therefore, despite the observed heterogeneity, symmetry is observed in the funnel plots.

Intragroup differences for HbA1c: Based on the meta-analysis conducted regarding the intragroup changes for the HbA1c variable, the three studies that provided the highest intragroup differences were Kim and Utz[39], Chen et al[13], and Alison and Anselm[36]. The first randomised clinical trial compared three groups. The first group was the control group, the second received an educational intervention for managing T2DM based on social networks and audiovisual material use, and the last one received an educational intervention based on telephone support without audiovisual aids. After 12 weeks of follow-up, the intervention group based on social network support and audiovisual material showed a 2.57-point decrease in HbA1c percentage, representing the most remarkable change among of the three groups. Similarly, Chen et al[13], in 2019, demonstrated that a nursing intervention based on interactive health education through the WeChat platform resulted in a significant intragroup change in HbA1c percentage of 2.23 points between preintervention and postintervention. Finally, Alison and Anselm[36] conducted a randomised clinical trial and concluded that health education combined with a pharmacology-based disease management program was of more significant benefit than only the educational program at the 12-month follow-up.

Intragroup differences for FPG: Based on the meta-analysis conducted regarding the intragroup changes for the FPG variable following a nursing intervention, the three studies that contributed the most remarkable intragroup differences were Moradi et al[15], Wu et al[17], and Elgerges[37]. Moradi et al[15] conducted an educational intervention through text messages to each patient’s phone. The text messages addressed topics primarily related to diabetic foot care and the recommendation of regular physician visits. After 3 months and after receiving 90 text messages the subjects who underwent the educational intervention not only improved their self-care and knowledge related to the diabetic foot but also substantially improved their glycaemic parameters. Wu et al[17] conducted a 6-month intervention study using Steno Balance Cards, a tool with which, through dialogue, participants could identify their own goals, problems, and solutions. In addition, they were used to encourage patient proactivity in managing their disease. Similarly, the results showed significant improvements in HbA1c and FPG levels.

Elgerges[37] conducted a randomized clinical trial of 100 patients divided into a control group that received a standard treatment for disease control and an experimental group that received an education programme under a multidisciplinary team and was provided with an educational kit and a pedometer for monitoring physical activity. This study showed statistically significant differences in this variable in both groups, but they were more prominent in the experimental group.

Intergroup differences for HbA1c: Based on the meta-analysis conducted regarding the intergroup changes for the HbA1c variable following a nursing intervention, the three studies demonstrating the greatest postintervention differences compared to the other intervention groups were Hoyo et al[38], Chen et al[13], and Moradi et al[15].

Hoyo et al[38] worked with one of the largest analysed cohorts, showing the best data observed in the meta-analysis (Figure 4). The researchers conducted a randomized controlled trial for 18 months on 384 patients, of whom 192 subjects belonged to the intervention group. In it, monthly telephone interventions conducted by specially trained research nurses were based on an individualised psychoeducational monitoring protocol that incorporated motivational interviewing and collaborative care strategies. Chen et al[13] demonstrated that in addition to the notable intragroup changes mentioned earlier, the experimental group also showed statistically significant intergroup differences with a P value of 0.004. Along similar lines, Moradi et al[15] with the use of text messages explained above substantially improved the plasma HbA1c levels of the treated patients concerning the control group, with values of 7.39 (1.44) vs 8.54 (1.81).

Intergroup differences for FPG: Based on the meta-analysis conducted regarding intergroup changes for the variable FPG following a nursing intervention, the three studies that showed the greatest differences at post-time compared to the other intervention groups were Moradi et al[15], Wu et al[17], and Subramanian et al[40].

The works of Moradi et al[15] and Wu et al[17] have shown the highest results at both intragroup and intergroup levels in the FPG analysis. In Moradi et al[15], the work with the most left-shifted results (Figure 5), the presence of elevated basal glycaemic levels in all study subjects was noted. This did not change in the control group after the intervention. In this case, at the intergroup level, the results of intervention vs control showed the figures of 180 (74) mg/dL vs 216 (93) mg/dL in the analysis of 80 vs 80 patients. However, in Wu et al[17], the results were 131.2 (32.3) mg/dL vs 165.0 (42.6) mg/dL. Subramanian et al[40] performed a nurse-led intervention featuring a 30-min video-assisted teaching session that addressed the nature of the disease, including information on diet, medication, hand and leg exercises, and home care management. This session was followed by a demonstration of hand and leg exercises with participants performing them themselves. In this case, the results were similar to Wu et al[17] [132.8 (42.87) mg/dL vs 161.57 (55.86) mg/dL].

The management of T2DM through health promotion is a comprehensive approach that has shown promising results, particularly in reducing HbA1c and FPG levels. In the present manuscript, several strategies related to educational interventions implemented by nurses were evaluated. They have been shown to be effective in controlling this disease, significantly improving glycaemic parameters compared to patients treated with traditional approaches.

The novel approach of the present manuscript has two aspects. On the one hand, a meta-analysis has been performed updating the state of the art of recent years, demonstrating that educational interventions from a nursing context can significantly improve quantitative parameters such as HbA1c and FPG. On the other hand, due to the combined quantitative study, it was possible to identify the studies with the most displaced results, allowing a narrative analysis of the type of intervention carried out on the patients. In this way, it has been possible to observe how nursing interventions that include follow-up, either face-to-face or telematic, have a significant beneficial effect on patient health compared to the traditional approach. Thus, studies such as that of Hoyo et al[38] or Subramanian et al[40] showed no variations in preintervention and postintervention follow-up glycaemic levels in their respective control groups. However, the results of the control group by Kim and Utz[39] or Chen et al[13] are also striking. In their 12-month and 3-month follow-ups, respectively, they observed decreases of about 1% in HbA1c or 1 mmol/L in FPG.

Of course, the baseline status of each subgroup is an essential factor to consider and a limitation of the results of some of the groups studied. Although most of them present homogeneity among the study groups, the manuscript by Subramanian et al[40] stands out negatively in this regard. As shown in Table 1, the baseline FPG values of the control group were 160.57 (58.7) mg/dL, while those of the intervention group were 146.7 (54.63) mg/dL.

Another factor to consider when comparing the effect of the different interventions is the follow-up time. Among the studies identified in the meta-analysis, the one by Hoyo et al[38] stands out with its 18-month intervention. Unsur

Furthermore, the combined quantitative data from the meta-analysis itself should be highlighted as well as the identification of the academic papers with the most substantial impact. Thus, the four intragroup and intergroup analyses performed in FPG and HbA1c have significantly demonstrated that nursing interventions focused on health education exert a beneficial effect on the progression and evolution of DM. The results observed in FPG are particularly striking but should be taken with caution since HbA1c levels better reflect the patient’s glycaemic status because it provides an estimate of the patient’s glycaemic status over the prior 3 months[41]. Therefore, in the face of numerous studies that perform a 3-month (or less) follow-up, a drastic change in a parameter that requires longer-term follow-up would not be observed. In any case, as can be seen in Figures 2, 3, 4, and 5, the P value calculated for the combined analysis of all the results was always statistically significant, typically less than 0.00001.

Another limitation of the study was the temporal restriction of the systematic review to the last 5 years to perform a paradigm update. We can find similarities in the systematic review by Chrvala et al[42], which revealed that T2DM education programs significantly reduced HbA1c levels, with an average decrease of about 0.6%. These educational interventions included informative sessions on diet, glucose monitoring, and the importance of physical exercise.

Another practical approach is individual and group consultations where nurses can provide personalized support and ongoing follow-up. According to the review by Duke et al[43], regular consultations with T2DM nurses resulted in a significant decrease in blood glucose and HbA1c levels compared to standard care. These interventions allowed for greater treatment adherence and better understanding of the disease by the patient. In this line, it is essential to highlight that active coping strategies combined with health promotion activities from nursing are crucial for effectively controlling T2DM. Therapeutic exercise, for example, has been identified as an effective intervention to reduce blood glucose levels and improve metabolic control. According to Colberg et al[44], regular exercise improves insulin sensitivity and reduces HbA1c levels in people with this disease. Thus, the combination of health education and therapeutic exercise may enhance the benefits of controlling T2DM. A study by Umpierre et al[45] showed that supervised exercise programs combined with DM education led to a more significant decrease in HbA1c levels compared to programs that only involves education. This evidence underscores the importance of a multifaceted strategy integrating different aspects of disease management.

Although pharmacological interventions are essential in managing T2DM, passive approaches, such as isolated medication administration, do not offer the same comprehensive benefits as active strategies. Passive interventions focus on symptomatic control rather than addressing the behaviours and habits contributing to poor glycaemic control. Additionally, passive interventions do not promote patient empowerment or significantly improve quality of life. In contrast, active strategies that involve the patient in self-management of the disease tend to produce better overall well-being and metabolic control outcomes. Powers et al[46] highlighted that DM self-management programmes, including education and ongoing support, substantially improved quality of life and reduced long-term complications.

Based on the exhaustive analysis of the literature and the evidence observed in the meta-analysis, it is proposed that nursing protocols for DM be improved by tailoring follow-ups to the patient’s technological knowledge (Supplementary material). Follow-up qualitatively and quantitatively improves patient quality of life and their biochemical parameters. Consequently, a nursing intervention program is proposed in which patients are subcategorized into three groups (A, B, or C) according to their technological proficiency (Supplementary Figure 1). For patients with good technological skills (Group A), mobile apps and social networks are recommended, and they will receive notifications and reminders through these platforms. For those with moderate skills (Group B), information will be provided through a webpage with a Q&A forum, and follow-up will be conducted via email and SMS. Finally, for those with little or no technological capability, the focus will be on face-to-face interactions and daily SMS reminders. Detailed information can be found in Supplementary material.

Through the analysis of recent literature, this work demonstrated that the implementation of active nursing care plans, which enhance patient follow-up, could improve the progression of DM by significantly reducing glycaemic variables such as blood glucose and HbA1c. Moreover, the novel approach of this manuscript allowed the identification of relevant studies through a meta-analysis, which confirmed the positive combined effect of the interventions at both the intragroup and intergroup levels. Finally, based on all the evidence described, the present manuscript proposed an improvement to the nursing care plan. We consider this plan essential to subclassify patients based on their technological skills to optimize the impact of the intervention plan, maximizing its effectiveness while minimizing effort. Ultimately, it could significantly enhance the quality of life for patients with DM.

We want to thank Rosalía Gómez-Toledano (philologist and English teacher for 37 years) for proofreading the manu

| 1. | Fan W. Epidemiology in diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Endocrinol. 2017;6:8-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S, Pinkepank M, Ogurtsova K, Duncan BB, Stein C, Basit A, Chan JCN, Mbanya JC, Pavkov ME, Ramachandaran A, Wild SH, James S, Herman WH, Zhang P, Bommer C, Kuo S, Boyko EJ, Magliano DJ. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;183:109119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3033] [Cited by in RCA: 4814] [Article Influence: 1604.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (36)] |

| 3. | Carrera Boada CA, Martínez-Moreno JM. Pathophysiology of diabetes mellitus type 2: beyond the duo "insulin resistance-secretion deficit". Nutr Hosp. 2013;28 Suppl 2:78-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Saeedi P, Petersohn I, Salpea P, Malanda B, Karuranga S, Unwin N, Colagiuri S, Guariguata L, Motala AA, Ogurtsova K, Shaw JE, Bright D, Williams R; IDF Diabetes Atlas Committee. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9(th) edition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;157:107843. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5345] [Cited by in RCA: 5938] [Article Influence: 989.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 5. | Davies MJ, Heller S, Skinner TC, Campbell MJ, Carey ME, Cradock S, Dallosso HM, Daly H, Doherty Y, Eaton S, Fox C, Oliver L, Rantell K, Rayman G, Khunti K; Diabetes Education and Self Management for Ongoing and Newly Diagnosed Collaborative. Effectiveness of the diabetes education and self management for ongoing and newly diagnosed (DESMOND) programme for people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008;336:491-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 517] [Cited by in RCA: 521] [Article Influence: 30.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Steinsbekk A, Rygg LØ, Lisulo M, Rise MB, Fretheim A. Group based diabetes self-management education compared to routine treatment for people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. A systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 495] [Cited by in RCA: 440] [Article Influence: 33.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wu L, Forbes A, Griffiths P, Milligan P, While A. Telephone follow-up to improve glycaemic control in patients with Type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials. Diabet Med. 2010;27:1217-1225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Arda Sürücü H, Büyükkaya Besen D, Erbil EY. Empowerment and Social Support as Predictors of Self-Care Behaviors and Glycemic Control in Individuals With Type 2 Diabetes. Clin Nurs Res. 2018;27:395-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kerr D, Ahn D, Waki K, Wang J, Breznen B, Klonoff DC. Digital Interventions for Self-Management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2024;26:e55757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13930] [Cited by in RCA: 13358] [Article Influence: 834.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52948] [Cited by in RCA: 47199] [Article Influence: 2949.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Huedo-Medina TB, Sánchez-Meca J, Marín-Martínez F, Botella J. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2 index? Psychol Methods. 2006;11:193-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2053] [Cited by in RCA: 2637] [Article Influence: 138.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chen L, Zhang W, Fu A, Zhou L, Zhang S. Effects of WeChat platform-based nursing intervention on disease severity and maternal and infant outcomes of patients with gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Transl Res. 2022;14:3143-3153. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Liu Y, Jiang X, Jiang H, Lin K, Li M, Ji L. A culturally sensitive nurse-led structured education programme in patients with type 2 diabetes. Int J Nurs Pract. 2019;25:e12757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Moradi A, Alavi SM, Salimi M, Nouhjah S, Shahvali EA. The effect of short message service (SMS) on knowledge and preventive behaviors of diabetic foot ulcer in patients with diabetes type 2. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2019;13:1255-1260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wei L, Wang J, Li Z, Zhang Y, Gao Y. Design and implementation of an Omaha System-based integrated nursing management model for patients with newly-diagnosed diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes. 2019;13:142-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wu YC, Kornelius E, Yang YS, Chen YF, Huang CN. An Educational Intervention Using Steno Balance Cards to Improve Glycemic Control in Patients With Poorly Controlled Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J Nurs Res. 2019;27:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mohamad RMA, Adhahi SK, Alhablany MN, Hussein HMA, Eltayb TM, Buraei SSEM, Alshamrani AA, Manqarah MS, Alhowiti DE, Aloqbi AM, Alatawi KAS, Aloqbi RM. Comparison of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Control at Home Healthcare and Hospital Clinic Care at King Salman Armed Forces Hospital (2021-2022): A Retrospective Cohort Study. Cureus. 2023;15:e48551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chen SM, Lin HS, Atherton JJ, MacIsaac RJ, Wu CJ. Effect of a mindfulness programme for long-term care residents with type 2 diabetes: A cluster randomised controlled trial measuring outcomes of glycaemic control, relocation stress and depression. Int J Older People Nurs. 2020;15:e12312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chiu CJ, Yu YC, Du YF, Yang YC, Chen JY, Wong LP, Tanasugarn C. Comparing a Social and Communication App, Telephone Intervention, and Usual Care for Diabetes Self-Management: 3-Arm Quasiexperimental Evaluation Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8:e14024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | De la Fuente Coria MC, Cruz-Cobo C, Santi-Cano MJ. Effectiveness of a primary care nurse delivered educational intervention for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in promoting metabolic control and compliance with long-term therapeutic targets: Randomised controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;101:103417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Qasim R, Masih S, Yousafzai MT, Shah H, Manan A, Shah Y, Yaqoob M, Razzaq A, Khan A, Rohilla ARK. Diabetes conversation map - a novel tool for diabetes management self-efficacy among type 2 diabetes patients in Pakistan: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Endocr Disord. 2020;20:88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Martos-Cabrera MB, Gómez-Urquiza JL, Cañadas-González G, Romero-Bejar JL, Suleiman-Martos N, Cañadas-De la Fuente GA, Albendín-García L. Nursing-Intense Health Education Intervention for Persons with Type 2 Diabetes: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Pereira PF, Santos JCD, Cortez DN, Reis IA, Torres HC. Evaluation of group education strategies and telephone intervention for type 2 diabetes. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2021;55:e03746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Risica PM, McCarthy ML, Barry KL, Oliverio SP, Gans KM, De Groot AS. Clinical outcomes of a community clinic-based lifestyle change program for prevention and management of metabolic syndrome: Results of the 'Vida Sana/Healthy Life' program. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0248473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sanaeinasab H, Saffari M, Yazdanparast D, Karimi Zarchi A, Al-Zaben F, Koenig HG, Pakpour AH. Effects of a health education program to promote healthy lifestyle and glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. Prim Care Diabetes. 2021;15:275-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ağralı H, Akyar İ. The effect of health literacy-based, health belief-constructed education on glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) in people with type 2 diabetes: A randomized controlled study. Prim Care Diabetes. 2022;16:173-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Guo J, Wang H, Ge L, Valimaki M, Wiley J, Whittemore R. Effectiveness of a nurse-led mindfulness stress-reduction intervention on diabetes distress, diabetes self-management, and HbA1c levels among people with type 2 diabetes: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Res Nurs Health. 2022;45:46-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Li S, Yin Z, Lesser J, Li C, Choi BY, Parra-Medina D, Flores B, Dennis B, Wang J. Community Health Worker-Led mHealth-Enabled Diabetes Self-management Education and Support Intervention in Rural Latino Adults: Single-Arm Feasibility Trial. JMIR Diabetes. 2022;7:e37534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ojewale LY, Oluwatosin OA. Family-integrated diabetes education for individuals with diabetes in South-west Nigeria. Ghana Med J. 2022;56:276-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Eshete A, Lambebo A, Mohammed S, Shewasinad S, Assefa Y. Effect of nutritional promotion intervention on dietary adherence among type II diabetes patients in North Shoa Zone Amhara Region: quasi-experimental study. J Health Popul Nutr. 2023;42:49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Eshete A, Mohammed S, Shine S, Eshetie Y, Assefa Y, Tadesse N. Effect of physical activity promotion program on adherence to physical exercise among patients with type II diabetes in North Shoa Zone Amhara region: a quasi-experimental study. BMC Public Health. 2023;23:709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Li F, Guo S, Gong W, Xie X, Liu N, Zhang Q, Zhao W, Cao M, Cao Y. Self-management of Diabetes for Empty Nest Older Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. West J Nurs Res. 2023;45:921-931. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Tuzon J, Mulkey DC. Implementing mobile text messaging on glycemic control in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2024;36:586-593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Xu HM, Zhai YP, Zhu WJ, Li M, Wu ZP, Wang P, Wang XJ. Application of hospital-community-home linkage management model in patients with type 2 diabetic nephropathy. J Health Popul Nutr. 2024;43:40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Alison C, Anselm S. The effectiveness of diabetes medication therapy adherence clinic to improve glycaemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomised controlled trial. Med J Malaysia. 2020;75:246-253. [PubMed] |

| 37. | ElGerges NS. Effects of therapeutic education on self-efficacy, self-care activities and glycemic control of type 2 diabetic patients in a primary healthcare center in Lebanon. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2020;19:813-821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Hoyo MLLD, Rodrigo MTF, Urcola-Pardo F, Monreal-Bartolomé A, Ruiz DCG, Borao MG, Alcázar ABA, Casbas JPM, Casas AA, Funcia MTA, Delgado JFR. The TELE-DD Randomised Controlled Trial on Treatment Adherence in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Comorbid Depression: Clinical Outcomes after 18-Month Follow-Up. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Kim SH, Utz S. Effectiveness of a Social Media-Based, Health Literacy-Sensitive Diabetes Self-Management Intervention: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2019;51:661-669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Subramanian SC, Porkodi A, Akila P. Effectiveness of nurse-led intervention on self-management, self-efficacy and blood glucose level among patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Complement Integr Med. 2020;17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Peer N, Balakrishna Y, Durao S. Screening for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;5:CD005266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Chrvala CA, Sherr D, Lipman RD. Diabetes self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review of the effect on glycemic control. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99:926-943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 643] [Cited by in RCA: 566] [Article Influence: 62.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Duke SA, Colagiuri S, Colagiuri R. Individual patient education for people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2009:CD005268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Colberg SR, Sigal RJ, Fernhall B, Regensteiner JG, Blissmer BJ, Rubin RR, Chasan-Taber L, Albright AL, Braun B; American College of Sports Medicine; American Diabetes Association. Exercise and type 2 diabetes: the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Diabetes Association: joint position statement. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:e147-e167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 869] [Cited by in RCA: 957] [Article Influence: 63.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Umpierre D, Ribeiro PA, Kramer CK, Leitão CB, Zucatti AT, Azevedo MJ, Gross JL, Ribeiro JP, Schaan BD. Physical activity advice only or structured exercise training and association with HbA1c levels in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;305:1790-1799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 985] [Cited by in RCA: 866] [Article Influence: 61.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Powers MA, Bardsley J, Cypress M, Duker P, Funnell MM, Fischl AH, Maryniuk MD, Siminerio L, Vivian E. Diabetes Self-Management Education and Support in Type 2 Diabetes: A Joint Position Statement of the American Diabetes Association, the American Association of Diabetes Educators, and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015;115:1323-1334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |