Published online Mar 15, 2024. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v15.i3.530

Peer-review started: November 2, 2023

First decision: November 21, 2023

Revised: December 5, 2023

Accepted: January 18, 2024

Article in press: January 18, 2024

Published online: March 15, 2024

Processing time: 134 Days and 9 Hours

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is one of the serious complications of diabetes mellitus, and the existing treatments cannot meet the needs of today's patients. Traditional Chinese medicine has been validated for its efficacy in DKD after many years of clinical application. However, the specific mechanism by which it works is still unclear. Elucidating the molecular mechanism of the Nardostachyos Radix et Rhizoma-rhubarb drug pair (NRDP) for the treatment of DKD will provide a new way of thinking for the research and development of new drugs.

To investigate the mechanism of the NRDP in DKD by network pharmacology combined with molecular docking, and then verify the initial findings by in vitro experiments.

The Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology (TCMSP) database was used to screen active ingredient targets of NRDP. Targets for DKD were obtained based on the Genecards, OMIM, and TTD databases. The VENNY 2.1 database was used to obtain DKD and NRDP intersection targets and their Venn diagram, and Cytoscape 3.9.0 was used to build a "drug-component-target-disease" network. The String database was used to construct protein interaction networks. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis and Gene Ontology analysis were performed based on the DAVID database. After selecting the targets and the active ingredients, Autodock software was used to perform molecular docking. In experimental validation using renal tubular epithelial cells (TCMK-1), we used the Cell Counting Kit-8 assay to detect the effect of NRDP on cell viability, with glucose solution used to mimic a hyperglycemic environment. Flow cytometry was used to detect the cell cycle progression and apoptosis. Western blot was used to detect the protein expression of STAT3, p-STAT3, BAX, BCL-2, Caspase9, and Caspase3.

A total of 10 active ingredients and 85 targets with 111 disease-related signaling pathways were obtained for NRDP. Enrichment analysis of KEGG pathways was performed to determine advanced glycation end products (AGEs)-receptor for AGEs (RAGE) signaling as the core pathway. Molecular docking showed good binding between each active ingredient and its core targets. In vitro experiments showed that NRDP inhibited the viability of TCMK-1 cells, blocked cell cycle progression in the G0/G1 phase, and reduced apoptosis in a concentration-dependent manner. Based on the results of Western blot analysis, NRDP differentially downregulated p-STAT3, BAX, Caspase3, and Caspase9 protein levels (P < 0.01 or P < 0.05). In addition, BAX/BCL-2 and p-STAT3/STAT3 ratios were reduced, while BCL-2 and STAT3 protein expression was upregulated (P < 0.01).

NRDP may upregulate BCL-2 and STAT3 protein expression, and downregulate BAX, Caspase3, and Caspase9 protein expression, thus activating the AGE-RAGE signaling pathway, inhibiting the vitality of TCMK-1 cells, reducing their apoptosis. and arresting them in the G0/G1 phase to protect them from damage by high glucose.

Core Tip: The Nardostachyos Radix et Rhizoma-rhubarb drug pair may upregulate BCL-2 and STAT3 protein expression, and downregulate BAX, Caspase3, and Caspase9 protein expression, thus activating the advanced glycation end products (AGEs)-receptor for AGEs signaling pathway, inhibiting the vitality of TCMK-1 cells, reducing their apoptosis, and arresting them in the G0/G1 phase to protect them from damage by high glucose.

- Citation: Che MY, Yuan L, Min J, Xu DJ, Lu DD, Liu WJ, Wang KL, Wang YY, Nan Y. Potential application of Nardostachyos Radix et Rhizoma-Rhubarb for the treatment of diabetic kidney disease based on network pharmacology and cell culture experimental verification. World J Diabetes 2024; 15(3): 530-551

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v15/i3/530.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v15.i3.530

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a clinical syndrome characterized mainly by elevated blood sugar caused by genetic factors. Delayed treatment will eventually lead to a series of serious complications, mainly diabetic kidney disease (DKD)[1]. DKD is one of the leading causes of end-stage renal disease, a leading cause of kidney failure. According to the epidemiological survey data released by the International Diabetes Federation, the global incidence of DM is 9.3%[2]; among them, 20%-40% develop DKD[3]. With the increase in the number of DKD patients, the treatment of DKD is imminent. The main treatment for DKD in Western medicine is to control blood sugar and improve renal function[4]. Clinical medications are mostly angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and sulfonylureas to improve renal blood circulation. Despite this, the effect of these medications in relieving symptoms and reducing the disease's progression is not obvious. Hence, we desperately need to find effective drugs or compounds with minimal side effects to treat DKD[5].

As a traditional Chinese medicine in China, Nardostachyos Radix et Rhizoma belongs to the dried roots and rhizomes of Nardostachys jatamansi, a plant of the Septoria family[6]. Modern pharmacological studies have found that it is effective against brain diseases, heart diseases, spleen diseases, skin diseases, erectile dysfunction, tumors, and other diseases[7]. The chemical components of Nardostachyos Radix et Rhizoma are mainly terpenoids, coumarin, and lignans[8]. The active compounds mansonopsin and naringin not only relieve cardiac hypertrophy[9] but also have anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, anti-osteoporosis, myocardium-protective, anti-malaria, liver-protective, anti-apoptosis, anti-tumor, sedative, antihypertensive, and anti-oxidative stress effects[10,11]. Other studies have shown that Nardostachyos Radix et Rhizoma can control blood glucose metabolism, regulate the islet function, and protect the kidney[12]. Rhubarb, which belongs to the dried roots and rhizome of Rheum officinale Baill in the Polygonum family, is widely utilized to cure diverse diseases. Rhubarb prevents the progression of DKD through a variety of mechanisms[13]. Modern pharmacological studies have found that anthraquinone derivatives contained in rhubarb have purgative effects[14]. Anthracene has an antidiarrheal effect. Emodin and rhein have anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antiviral, anti-oxidative stress, anti-tumor, anti-fibrosis, lipid-regulating, and hypoglycemic effects[15,16]. Rhubarb tannin improves nitrogen waste metabolism; rhubarb anthraquinone and rhubarb anthraquinone glucoside can inhibit mesangial cell growth, improve renal tubular function, and protect the kidney[17]. Rhein has antitumor effects[18]. In addition, it has hemostatic, antiviral, antibacterial, liver-protecting[19], gallbladder-protecting, stomach-protecting[20], and kidney-protecting properties. In the treatment of DKD, rhubarb can reduce uremic toxin levels, regulate intestinal flora[14], and delay the progression of renal interstitial fibrosis. However, the drug targets and molecular mechanisms of Nardostachyos Radix et Rhizoma-rhubarb drug pair (NRDP) in the treatment of DKD have not been clarified. Therefore, we investigated the specific drug targets and molecular mechanisms of NRDP in the treatment of DKD based on network pharmacology combined with pharmacology.

DM and aberrant renal function are the causes of DKD. While the precise etiology remains unknown, certain research has demonstrated that advanced glycation end products (AGEs) formation is essential to the development of DKD. When the receptor for AGEs (RAGE) is activated, other associated pathways are impacted, which increases oxidative stress and inflammation in renal cells, encouraging apoptosis and exacerbating the progression of DKD[21]. Traditional Chinese medicine is often used to treat chronic diseases. Under high-glucose environment, the AGE-RAGE pathway will be activated to increase kidney damage. Studies have shown that traditional Chinese medicine monomers and compounds can regulate PI3K-AKT, NF-κB, JAK/STAT, and other pathways, and reduce oxidative stress, cell apoptosis, and inflammation, thereby improving kidney damage and delaying the course of DKD[22]. Since there have been few reports on the effects and mechanisms of NRDP in treating DKD, we analyzed the active components and targets of NRDP, and explored the mechanism underlying the therapeutic effects of NRDP on DKD in the present study.

Traditional Chinese medicine compounds exhibit multi-target, multi-component, and multi-pathway actions that are consistent with network pharmacology. In this study, we employed network pharmacology and experimental verification to confirm the mechanism of action of the compound on DKD. We searched for drug and disease targets using the TCMSP, Gene Cards, OMIM, and TTD databases, and then identified the core target pathway through the protein-protein interaction (PPI) network. Using NRDP components, we conducted Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses, as well as molecular docking. Finally, we performed experimental verification to prove the predictions made on the mechanism of NRDP in DKD (Figure 1), with an aim to provide new ideas and methods for the subsequent treatment of DKD with traditional Chinese medicine.

The TCMSP database analysis platform (https://tcmsp-e.com/) was searched for the active ingredients and targets of Nardostachyos Radix et Rhizoma and rhubarb. The screening criteria for the active ingredients in drugs and their corresponding were oral availability ≥ 30% and drug likeness ≥ 0.18. Then, the UniProt (https://www.uniprot.org/) database was used to translate the targets into gene names.

In the GeneCards (http://www.genecards.org/), OMIM (http://omim.org/), and TTD (https://db.idrblab.net/ttd/) databases, "Diabetic Kidney Diseases" and "Diabetic Nephropathy" were searched as keywords, and the DKD targets were obtained.

The Venny2.1.0 platform (https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/) was used to obtain the common targets between the NRDP and DKD.

To visualize the results, a "component-target-disease" network was constructed using Cytoscape 3.9.0 with the active ingredients and targets of NRDP and DKD.

PPI network diagrams were constructed by importing the common targets of NRDP and DKD into the STRING 11.5 database (https://cn.string-db.org/), and the species was set as "Homo sapiens". The minimum interaction threshold was set as "highest confidence" (> 0.9), to hide isolated nodes, and the rest of the settings were set as default. To obtain protein interaction data, the TSV file was downloaded and imported to Cytoscape software. The Network Analyzer plug-in was used to analyze network characteristics, and screen core targets in the PPI network according to the degree of nodes.

Cytoscape software was used to construct a network for common targets and NRDP active components. To analyze the characteristics of the network, the Network Analyzer plug-in was used, and the interaction between NRDP active components and core targets was analyzed according to the degree of nodes.

Intersection targets were imported to the DAVID database (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/) for GO function and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis. P value < 0.01 and false discovery rate < 0.01 were used the conditions for the screening. With the help of online data analysis, the visualization platform - microscopic letter (http://www.bioin

The key pathway targets obtained following KEGG enrichment were used to generate a full PPI network based on the STRING11.5 database. The TSV file of PPI was downloaded and imported into Cytoscape software. After analysis with the Network Analyzer plug-in, a component-target network diagram about the pathway was reconstructed with the active components of NRDP. According to the degree of the node, the interaction between the active components of NRDP and the pathway targets was analyzed.

NRDP medicine mol2 structures were downloaded from the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), and the core target protein 3D structure was downloaded from the PDB database (https://www.rcsb.org/). Then, the water molecules and small molecular ligands of proteins were removed using Pymol 2.4.0 software, and AutoDock 1.5.7 software was employed for hydrogenation. Molecular docking of receptor and ligand was performed and their binding activity was evaluated.

Cells: TCMK-1 cells (renal tubule epithelial cells) were purchased from BeNa Culture Collection (No. BNCC339820).

Drugs and reagents: NRDP was prepared by the Preparation Center, Affiliated Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Ningxia Medical University.

Cell culture: TCMK-1 cells were cultured with complete medium (89% high-glucose DMEM + 10% fetal bovine serum + 1% penicillin-streptomycin mixture) in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. A microscope was used to observe cell growth, and cells were passed at 80% confluence.

TCMK-1 cells in the logarithmic growth phase were digested with trypsin for cell suspension preparation. Cells were counted under a 20 times microscope, and 5 × 103 cells were inoculated per well into 96-well plates and incubated with complete cell culture medium (control group), 60 mmol/L high glucose culture medium (model group), or high glucose culture medium + different concentrations of NRDP (NRDP groups), with each group having five replicate wells. NRDP was diluted multiple times according to the drug concentration gradient, and then 100 μL of the diluted NRDP solution was added to each well and incubated for 24 h. At the end of the drug intervention, incubation with CCK8 (10 μL/well) was performed for 1 h under no light conditions. Optical density (OD) was then read at 450 nm.

TCMK-1 cells in the logarithmic growth phase were divided into five groups: Control group (complete culture medium), model group (60 mmol/L high-glucose culture medium), low-dose group (high-glucose culture medium + 4 mg/mL NRDP), medium-dose group (high-glucose culture medium + 7 mg/mL NRDP), and high-dose group (high-glucose culture medium + 10 mg/mL NRDP). Three replicates were run for each group. Cells were inoculated into 6-well plates at a density of 1.0 × 105 cells/well. Following 24 h of culture in an incubator, serum-free medium was added to each group and incubated for 12 h. Cells were then digested, fixed overnight, and pre-cooled by adding 70% ethanol. A commercial cell cycle kit (KeyGEN Biotech, China) was used to detect the cell cycle progression with a CytoFLEX flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, United States).

TCMK-1 cells in the logarithmic growth phase were divided into five groups as stated above, and three replicates were run for each group. Cells were inoculated into 6-well plates at a density of 1.0 × 105 cells/well. Following 24 h of culture in an incubator, each group of cells were exposed to the corresponding culture medium. After cells were digested and collected, the corresponding reagents were added according to the Annexin V-FITC/propidium iodide apoptosis detection kit (KeyGEN Biotech, China) instructions. The results were detected with a CytoFLEX flow cytometry (Beckman Coulter, United States).

TCMK-1 cells in the logarithmic growth phase were divided into three groups: Control group, model group, and medium dose group (7 mg/mL NRDP), and three replicates were run for each group. After cells were digested and collected, 200 μL of RIPA lysis buffer was added according to the total protein extraction kit (KeyGEN Biotech, China) instructions. The extracted proteins was subjected to protein content determination and then resolved by SDS-PAGE. After transfer to a membrane and membrane blockade, the membrane was incubated with the primary antibody at 4 °C overnight, followed by incubation with the secondary antibody for 1 h. Chemidoc (Ge1Doc XR+, BIO-RAD, United States) was used for chemiluminescence detection. Image J software was used to determine gray values for statistical analysis.

GraphPad Prism 8.0.2 software was used for statistical analyses and one-way analysis of variance was used to compare the difference among groups. The SNK test was used to test for homogeneity of variances, and the Tamhane's T test was used to test for heterogeneity of variances. P values < 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant.

A total of 15 active ingredients were obtained from the TCMSP database, including five active ingredients from Nardostachyos Radix et Rhizoma and ten from rhubarb. After removing duplicate targets, 43 targets of Nardostachyos Radix et Rhizoma, 69 targets of rhubarb, and 85 GRDP targets were obtained (Figure 2A).

Based on GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/), OMIM (https://omim.org/), DrugBank (https://go.drug

The NRDP active ingredients and common targets were imported into Cytoscape 3.9.0 software to obtain a visualized regulatory network diagram (Figure 2C). The nodes in the diagram include drug, disease, active ingredient, and target, where the edges indicate that there is an interrelationship between them. Orange represents diseases and drugs. Fuchsia represents the co-interacting active ingredients of NRDP-disease. Light blue represents the active ingredients of Nardostachyos Radix et Rhizoma. Light yellow represents the active ingredients of rhubarb. Light purple represents gene targets for NRDP-disease co-action. Pink represents the target genes for NRDP. Light orange represents target genes for rhubarb. This network diagram shows that NRDP works through multiple components and targets in the treatment of DKD.

Using the STRING database, we obtained the protein interaction network diagram of NRDP and DKD (Figure 2D). There are 54 nodes and 310 edges, with the nodes representing proteins.

The TSV file of the above PPI network diagram was downloaded, and the Network Analyzer plug-in in Cytoscape was used to analyze the network characteristics, including 54 nodes and 178 edges. Nodes with a degree median greater than 13 were carded out to obtain the PPI network, including the core targets of NRDP for DKD treatment. The targets were TP53, STAT3, HSP90AA1, JUN, RELA, ESR1, CCND1, MYC, CDKN1A, NR3C1, and CDK1. The results are shown in Figure 2E.

A network diagram was constructed between PPI targets and NRDP active components. Through analysis with the Network Analyzer plug-in in Cytoscape software, the interaction between NRDP active components and 54 targets and their degree values were obtained. Nodes with a median of greater than 13 degrees were identified. Seven main components were obtained, including aloe-emodin, cryptotanshinone, EUPATIN, rhein, and acacetin, as shown in Figure 2F.

A total of 1528 biological process entries were obtained after GO enrichment analysis, which mainly involves response to oxygen-containing compound and response to organic cyclic compound, cellular response to chemical stimulus, cellular response to oxygen-containing compound, etc. There were 107 cell composition items, including the membrane raft, cytoplasmic part, an integral component of the presynaptic membrane and plasma membrane, extracellular exosome, and cytosol. There were 115 molecular function entries, mainly involving enzyme binding, protein domain-specific binding, transcription factor activity, direct ligand regulated sequence-specific DNA binding, etc. The top 10 enrichment results of each group are plotted (Figure 3A). The KEGG pathway enrichment analysis identified 111 pathways. The top 20 pathways are plotted in Figure 3B. The important pathways involved in the therapeutic effects of NRDP on DKD include pathways in cancer, PI3K-AKT signaling pathway, p53 signaling pathway, AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications, and apoptosis signaling pathway. The AGE-RAGE signaling pathway is the core pathway. The component-target network diagram in the signal pathway was constructed with NRDP active components using the STRING11.5 database and Network Analyzer plug-in of Cytoscape software, as shown in Figure 3C. The signal pathway diagram was also generated (Figure 3D).

To further analyze the feasibility of NRDP for the treatment of DKD, the core proteins TP53, STAT3, HSP90AA1, JUN, RELA, ESR1, and CCND1, which have top seven degree values, were molecularly docked with the active components of NRDP. The PDB ID of ESR1, RELA, TP53, HSP90AA1, JUN, CCND1, and STAT3 is 6CHW, 3CBQ, 3DCY, 1BYQ, 2P33, 2VTH, and 6NJS, respectively. Pymol software was used to visualize the docking results (Figure 4A). Binding activity was evaluated according to docking scores: Scores < -4.25 kcal/mol indicated low binding activity, scores < -5.0 kcal/mol indicated good binding activity, and scores < -7.0 kcal/mol indicated strong binding activity. ChiPlot (https://www.chiplot.online/#Heatmap) online tools were used for the visualization output (Figure 4B). The binding energy of the ten active ingredients with the seven core target proteins was all less than -5.0 kcal/mol, among which the binding energy of STAT3 and (-) -Catechin was the smallest at -9.3 kcal/mol.

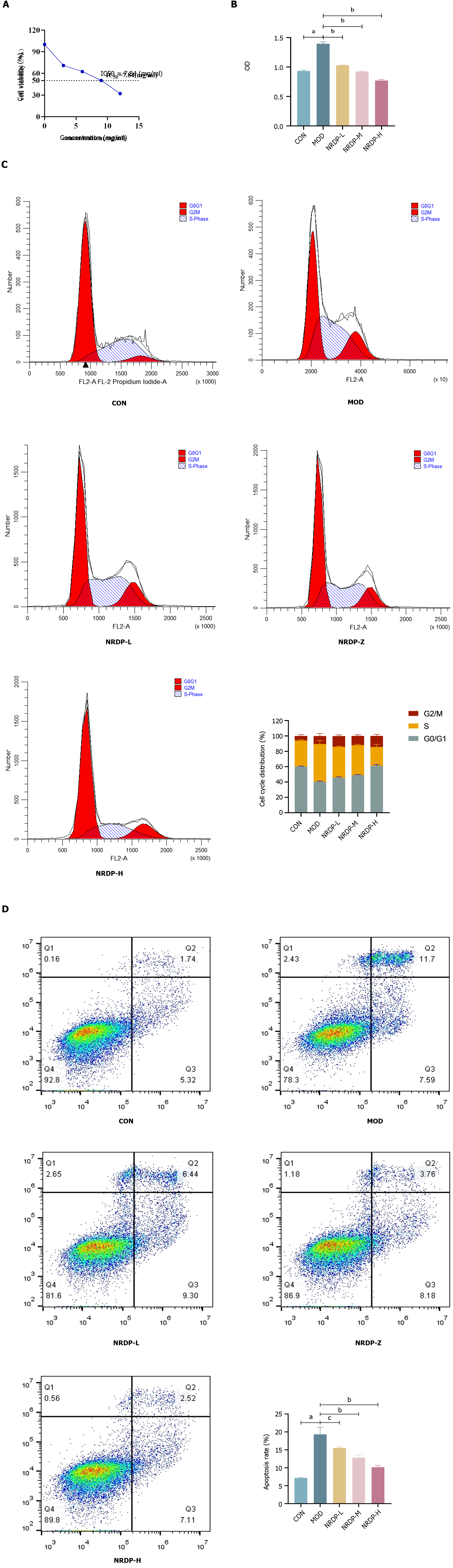

To determine the inhibition rate of NRDP in each group, the OD values from the 24-h experiment were used for inhibition rate calculation. With GraphPad Prism 8.0.2, half-inhibitory doses for TCMK-1 cells were fitted (Figure 5A). According to the experimental results, the IC50 (half maximal inhibitory concentration) value of NRDP was 7.84 mg/mL. We determined that the half inhibitory concentration was 7 mg/mL, and the optimal low-, medium-, and high-does administration concentration was 4 mg/m, 7 mg/mL, and 10 mg/mL, respectively. Cell Counting Kit-8 assay showed that compared with that of the control group, the cell viability of the model group was significantly increased (P < 0.01). Compared with the model group, TCMK-1 cell viability decreased after NRDP intervention (P < 0.01) in a dose-dependent manner. The higher the NRDP dose, the more obvious the decline in TCMK-1 cell viability (Figure 5B).

After 24 h of NRDP intervention, flow cytometry was used to determine the cell cycle of TCMK-1 cells. Compared to cells in the control group (60.1 ± 0.70), cells of the model group showed an increase in the percentage of cells in the G0/G1 phase (40.23 ± 1.07; P < 0.01). Compared with the model group, the percentage of cells in the G0/G1 phase increased and that of the cells in the S phase decreased after NRDP intervention (NRDP-L: 45.55 ± 1.23, NRDP-M: 48.93 ± 0.75, NRDP-H: 61.04 ± 1.66; P < 0.01). Thus, NRDP could block TCMK-1 cells in the G0/G1 phase (Figure 5C).

Apoptosis of TCMK-1 cells was detected by AV-PI double staining and flow cytomety after 24 h of NRDP intervention. Compared with that of the control group (7.17 ± 0.168), the apoptosis rate of TCMK-1 cells in the model group was significantly increased (19.32 ± 1.975; P < 0.01). Compared with that of the model group, the apoptosis rate in the NRDP groups was decreased (P < 0.01), and with the increase of NRDP concentration, the apoptosis rate of TCMK-1 cells decreased more significantly (NRDP-L: 15.55 ± 0.257, NRDP-M: 12.80 ± 0.773, NRDP-H: 10.18 ± 0.523; Figure 5D).

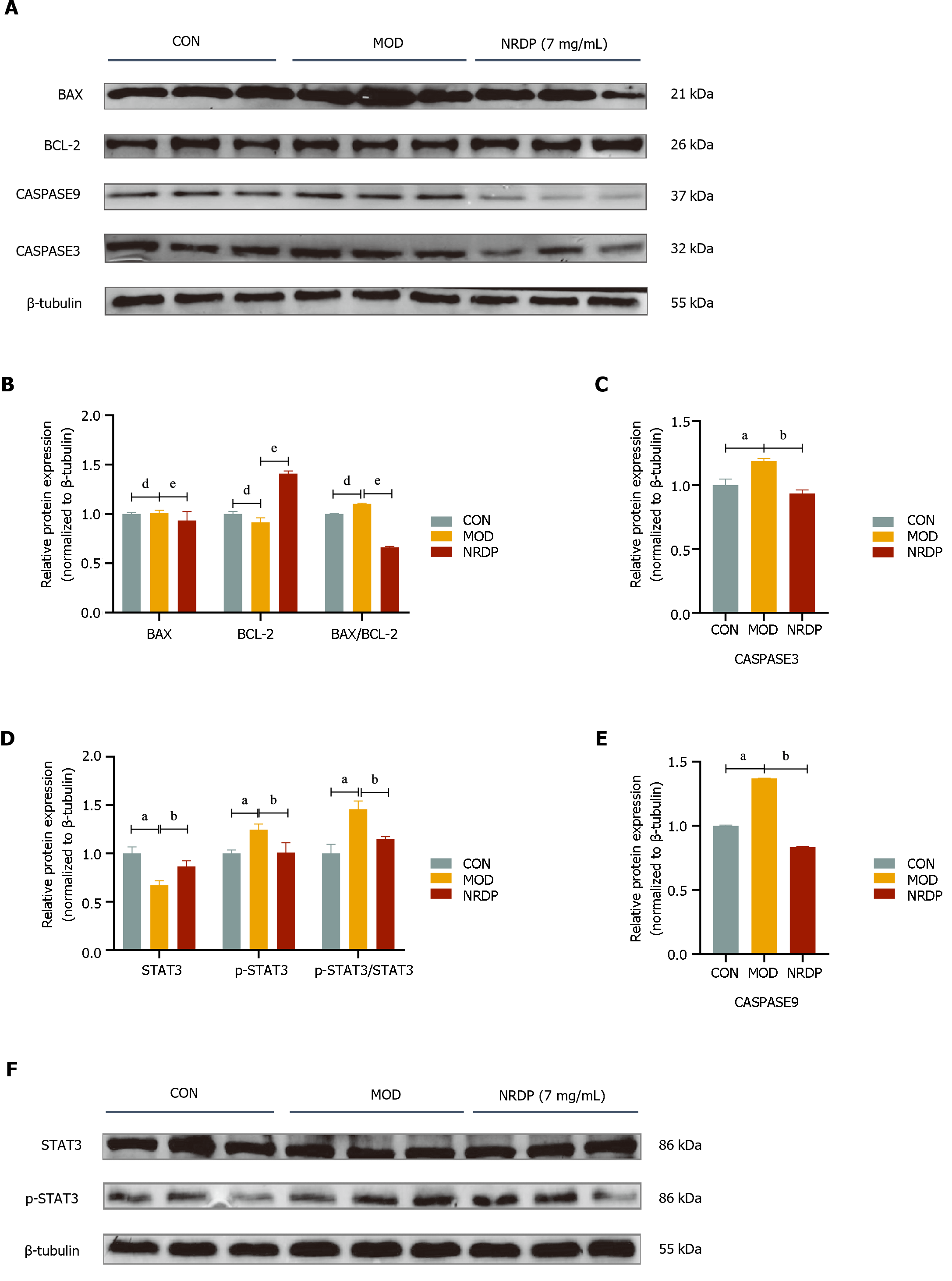

Western blot was used to detect the expression of core proteins in TCMK-1 cells after NRDP intervention. The expression of p-STAT3, BAX, Caspase3, and Caspase9, as well as BAX/BCL-2 and p-STAT3/STAT3 ratios, was increased in the model group compared with the control group (P < 0.01), while the expression of BCL-2 and STAT3 proteins was decreased (P < 0.01). After intervention with NRDP, the expression of p-STAT3, BAX, Caspase3, and Caspase9, as well as BAX/BCL-2 and p-STAT3/STAT3 ratios, was decreased (P < 0.01 or P < 0.05), and the expression of BCL-2 and STAT3 proteins was increased (P < 0.01) (Figure 6).

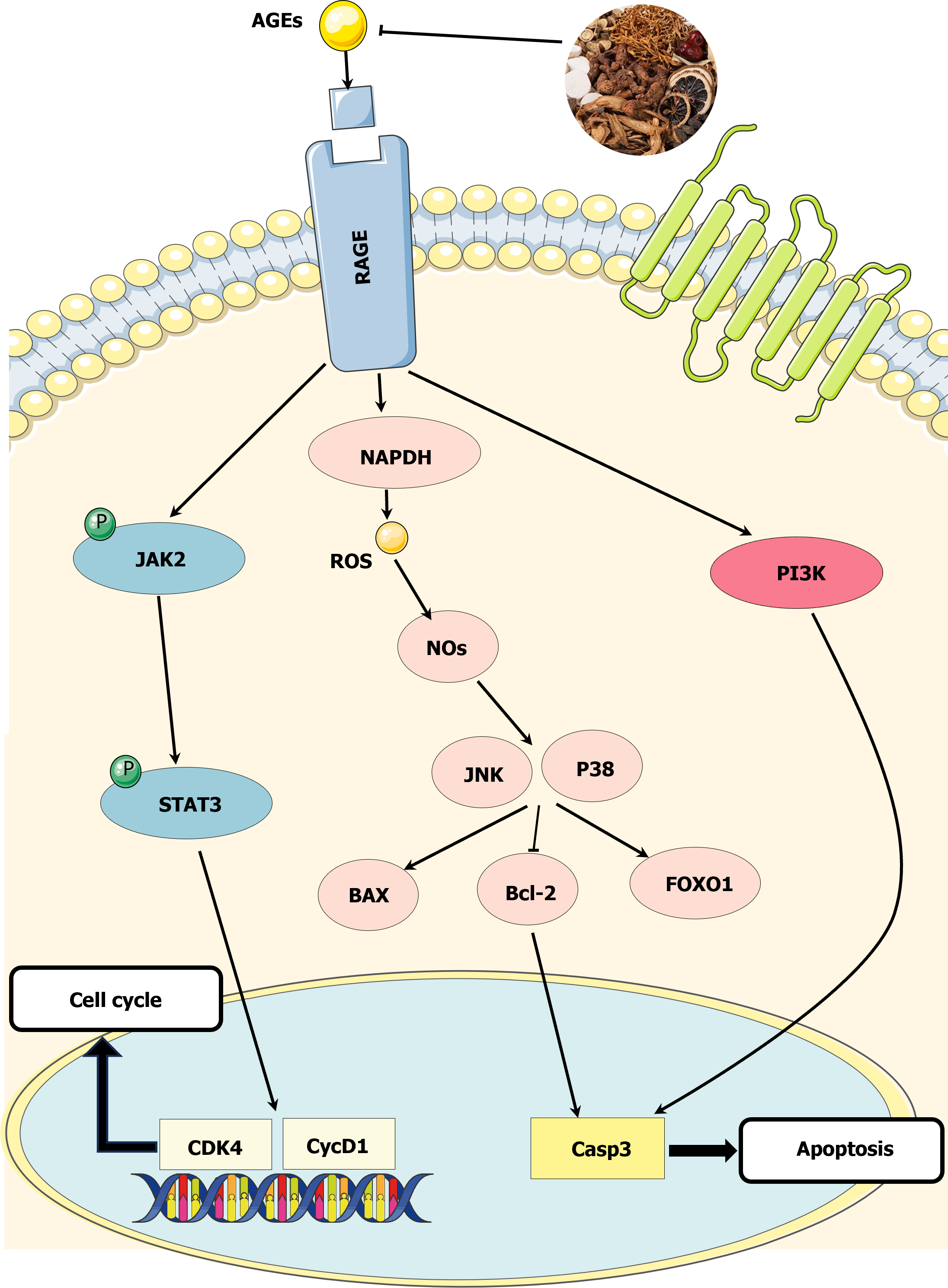

This study investigated the mechanism of action of NRDP on DKD using network pharmacology. The results showed that NRDP had a therapeutic effect on DKD, with 10 active ingredients involving 85 targets. The GO, KEGG, and network interaction analyses revealed that NRDP may act on DKD through the AGE-RAGE signaling pathway (Figure 7). Our in vitro cell experiments confirmed that NRDP significantly inhibited TCMK-1 proliferation, promoted cell cycle arrest at the G0/G1 phase, and reduced the apoptosis of TCMK-1 cells in a dose-dependent manner. The results of the Western blot analysis indicated that NRDP intervention led to up-regulation of BCL-2 and STAT3 protein expression, and down-regulation of p-STAT3, BAX, Caspase3, and Caspase9 protein expression. Additionally, the BAX/BCL-2 and p-STAT3/STAT3 ratios were reduced. These findings suggest that NRDP is an effective treatment for DKD. NRDP protects renal tubular epithelial cells from high glucose-induced damage by regulating the AGE-RAGE signaling pathway.

AGEs are a group of complex molecules that form through non-enzymatic reactions between proteins or lipids and glucose or other carbohydrate derivatives. Their receptor RAGE is a multi-ligand receptor belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily and is expressed in a wide range of tissues, including the vascular system, lung, heart, endothelial, and nervous tissues[23]. Their binding forms a key pathophysiological process associated with the occurrence and progression of many diseases, especially diabetes complications. AGEs from hyperglycemia interact with RAGE to activate many downstream effectors, including the JAK/STAT pathway, which in turn activates transcription factors like STAT3 over time[24]. This increases the inflammatory response and further exacerbates DKD[25]. Tang et al[26] showed through network pharmacology that the AGE-RAGE pathway is the most important pathway for Coptis Jiedu decoction to treat DKD, and in vivo experiments verified that Coptis Jiedu decoction can improve glucose and lipid metabolism disorder and kidney injury by regulating the AGEs-RAGE-AKT-Nrf2 pathway in db/db mice, thus playing a protective role in DKD. Hou et al[27] showed that salvianolic acid A inhibited AGEs-induced actin cytoskeletal rearrangement through the AGEs-RAGE-Rhoa-Rock pathway, restored glomerular endothelial permeability, weakened AGEs-induced oxidative stress, restored glomerular endothelial function, alleviated renal structural deterioration, and effectively improved early DKD. The changes in the expression of relevant proteins after NRDP intervention in this study showed that the drug alleviated DKD symptoms to some extent.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that the production of AGEs linked to hyperglycemia is a key factor in the pathophysiology of DKD. The RAGE binds to its ligands, inducing oxidative stress and chronic inflammation in renal tissue, ultimately resulting in renal dysfunction. AGEs can alter the extracellular matrix by involving cell surface receptors and producing proinflammatory cytokines. RAGE and its ligands promote angiogenesis, cell migration, proliferation, invasion, and metastasis by limiting apoptotic cell death[28]. Studies have shown that AGEs and their receptor RAGE can induce apoptosis in different cell types. The propagation of apoptosis through the AGE-RAGE signaling pathway involves the cascade reaction of the pro-apoptotic factor, which prompts the apoptotic signal to activate the apoptotic factor Caspase3[29] and initiates the occurrence of apoptosis. Under the influence of certain receptors and factors, the endogenous apoptotic pathway is activated and regulated by the BCL-2 protein, which directly activates Caspase9. The Caspase cascade can activate Caspase3 during apoptosis induced by death receptors and DNA damage, producing intracellular signals that act on cellular targets, ultimately leading to programmed cell death[30]. Previous studies have demonstrated that RAGE expression regulates apoptotic death receptors and mitochondrial pathways by controlling the expression of pro-apoptotic Caspase3, Caspase9, and anti-apoptotic BCL-2. BAX, a proapoptotic protein, and BCL-2, a regulatory protein of apoptosis, can form Bax-Bcl-2 heterodimers when BCL-2 binds to active BAX protein in the cytoplasm, thus playing a role in reducing apoptosis. Reducing the activity of the BAX protein can also negatively regulate apoptosis. The amount of apoptosis can be determined by the degree of binding between BAX and BCL-2. Reducing the activity of BAX and promoting the binding of BCL-2 to BAX protein can reduce apoptosis[31]. Our study found that the expression of apoptosis-related proteins in TCMK-1 cells was detected after the intervention of NRDP. The expression of BAX, Caspase3, and Caspase9 proteins was downregulated, while the expression of BCL-2 protein was upregulated. This may be due to the induction of BCL-2 expression by NRDP. The inhibition of BAX protein activity resulted in a weakened Caspase family cascade and reduced apoptosis of renal tubular epithelial cells. This illustrates the pharmacological effect of NRDP in treating DKD.

In summary, NRDP may prevent TCMK-1 cells from proliferating and reduce cell death by controlling the relevant proteins of the AGE-RAGE signaling pathway, thereby protecting the function of intrinsic kidney cells during high glucose levels. Currently, there are numerous studies on the pathogenesis of DKD, which can be summarized as the result of a combination of metabolic, inflammatory, hemodynamic, and fibrotic factors. Many scholars have explored the treatment of DKD. Some treatments targeting specific pathogenic mechanisms are often used in clinical and experimental studies. Combination therapies involving two or more drugs have been found to have the potential to treat DKD. For instance, combining ERA with SGLT2 inhibitors has shown promise[32]. The present study also validated the efficacy of a herbal combination for treating DKD, providing a preliminary possibility for future exploration of new combinations of traditional Chinese medicine combined with other inhibitors and drugs for treating DKD. However, this study was only limited to in vitro cellular experiments due to funding constraints. Our group's research on treating DKD with traditional Chinese medicine is ongoing, and we plan to incorporate high-throughput histological methods for further validation in the future. We will use high-throughput genomics methods for the validation and identification of a safe and effective clinical treatment for DKD, which will improve the prognosis and quality of life of such patients.

In this study, TCMK-1 cells were treated with varying concentrations of NRDP in a hyperglycemic environment. The results indicated that NRDP can regulate the cell cycle of TCMK-1 cells by blocking them in the G0/G1 phase, affecting the process from the late stage of DNA synthesis to the completion of mitosis and reducing apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner. Additionally, NRDP may upregulate the expression of BCL-2 and STAT3. The expression of p-STAT3, BAX, Caspase3, and Caspase9 proteins was downregulated, as well as the BAX/BCL-2 and p-STAT3/STAT3 ratios. Consequently, the impaired AGE-RAGE signal axis has a greater impact on the body during high glucose conditions, and the high glucose environment has a protective effect on renal tubular epithelial cells. This lays the foundation for the search for safe and effective drugs to treat DKD.

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is one of the serious complications of diabetes mellitus. It has a poor prognosis and is one of the causes of end-stage renal disease. Existing treatments can improve the symptoms of DKD to some extent. However, they have the disadvantages of side effects and high price.

We performed in vitro cellular experiments to validate the effectiveness of the Nardostachyos Radix et Rhizoma-rhubarb drug pair (NRDP) and to provide new ideas for clinical treatment of DKD.

In this study, we used network pharmacology and molecular docking to predict the targets of NRDP for the treatment of DKD and validated the prediction findings using cellular experiments.

Targets for NRDP and DKD were obtained using databases such as TCMSP, Genecards, OMIM, and TTD. Drug-disease intersection targets were obtained based on the VENNY 2.1 database and "drug-component-target-disease" network was constructed. Afterward, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway and Gene Ontology enrichment analyses were performed to further observe the relationship between targets and pathways. Finally, molecular docking was performed on the active ingredients of NRDP. Experiments such as the CCK-8 method, flow cytometry, and Western Blot were used to verify the molecular mechanism of NRDP for DKD.

NRDP may inhibit the viability of high glucose-induced TCMK-1 cells by modulating the advanced glycation end products (AGEs)-receptor for AGEs (RAGE) signaling pathway, thereby blocking cell cycle progression in the G0/G1 phase and reducing apoptosis. It also downregulated the protein expression of p-STAT3, BAX, Caspase3, and Caspase9, and up-regulated the protein levels of BCL-2 and STAT3. These findings verified that NRDP could reduce high glucose-induced TCMK-1 cell injury, thereby restoring their function.

NRDP may achieve its therapeutic effect on DKD by modulating the AGE-RAGE signaling pathway. NRDP arrests the cell cycle progression at the G0/G1 phase by inhibiting the proliferation of high glucose-induced TCMK-1 cells and reducing their apoptosis. NRDP inhibits the expression of proteins related to the AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in high glucose environment, which delays the progression of DKD.

We next plan to conduct in vivo animal and omics experiments. To determine the specific components of NRDP in the blood for the treatment of DKD, gene detection will be performed by high-throughput validation methods such as transcriptomics, in order to provide a safe and effective method for clinical treatment of DKD.

We would like to thank the Ningxia Medical University Key Laboratory of Ningxia Minority Medicine Modernization Ministry of Education for providing the experimental platform, and Ying-Feng Ma, Xiao-Li Du, Ting-Ting Li, and Lei Zhang for their help. And grateful for the financial support.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Endocrinology and metabolism

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cai L, United States; Cigrovski Berkovic M, Croatia; Dąbrowski M, Poland; Emran TB, Bangladesh; Kode JA, India; Odhar HA, Iraq; Zhou X, China S-Editor: Lin C L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Chen YX

| 1. | Flyvbjerg A. The role of the complement system in diabetic nephropathy. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2017;13:311-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 293] [Article Influence: 36.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S, Pinkepank M, Ogurtsova K, Duncan BB, Stein C, Basit A, Chan JCN, Mbanya JC, Pavkov ME, Ramachandaran A, Wild SH, James S, Herman WH, Zhang P, Bommer C, Kuo S, Boyko EJ, Magliano DJ. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;183:109119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3033] [Cited by in RCA: 4813] [Article Influence: 1604.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (36)] |

| 3. | Bonner R, Albajrami O, Hudspeth J, Upadhyay A. Diabetic Kidney Disease. Prim Care. 2020;47:645-659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Limonte CP, Kretzler M, Pennathur S, Pop-Busui R, de Boer IH. Present and future directions in diabetic kidney disease. J Diabetes Complications. 2022;36:108357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tang G, Li S, Zhang C, Chen H, Wang N, Feng Y. Clinical efficacies, underlying mechanisms and molecular targets of Chinese medicines for diabetic nephropathy treatment and management. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2021;11:2749-2767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 48.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Le VNH, Khong TQ, Na MK, Kim KT, Kang JS. An optimized HPLC-UV method for quantitatively determining sesquiterpenes in Nardostachyos Radix et Rhizoma. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2017;145:406-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rao Y, Li R, Wang XW, Xue BX, Li SW, Zhao Y, Zhang LH, Xu JT, Wu HH. Data mining of medication patterns in Gan Song Chinese medicine. Zhongcaoyao. 2021;52:3331-3343. |

| 8. | Dhiman N, Bhattacharya A. Nardostachys jatamansi (D.Don) DC.-Challenges and opportunities of harnessing the untapped medicinal plant from the Himalayas. J Ethnopharmacol. 2020;246:112211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Shuyuan L, Haoyu C. Mechanism of Nardostachyos Radix et Rhizoma-Salidroside in the treatment of premature ventricular beats based on network pharmacology and molecular docking. Sci Rep. 2023;13:20741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lee GW, Hur W, Kim JH, Park DJ, Kim SM, Kang BY, Sung PS, Yoon SK. Nardostachys jatamansi Root Extract Attenuates Tumor Progression in Hepatocellular Carcinoma via Inhibition of ERK/STAT3 Pathways. Anticancer Res. 2021;41:1883-1893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ai YZ, Ma XJ, Xing YX, Yan LM, Gao AR, Xu QW, Xu ZJ, Wu XY, Gao HR, Zhang JC. Network-based pharmacological analysis of the molecular mechanism of liver-regulating, qi-benefiting, and palpitation-determining drugs on Gan Song-Xianhe Cao in the treatment of cardiac arrhythmias. Zhongguo Shiyan Fangjixue Zazhi. 28:204-11. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Ran B. Clinical observation on Gan Song Glucose-lowering Granules in the treatment of newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus (spleen-kidney deficiency and blood stasis type) M.Sc. Thesis, Ningxia Medical University. 2021. Available from: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=xBNwvqFr00IJmnSCc9uj6Cua6bEgKwCGHOfSr7HuDwwrKy4RZUzIjnp3jjujbowGqYFkGsfTFgTRZIB1ki0W5xMNBmxmbio2OVBk4h6pB2W5XSMnZ9XF6gtNSe0YUfoqu08Ua3igtRy-f9X9apxmTA==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS. |

| 13. | Fu S, Zhou Y, Hu C, Xu Z, Hou J. Network pharmacology and molecular docking technology-based predictive study of the active ingredients and potential targets of rhubarb for the treatment of diabetic nephropathy. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2022;22:210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yang L, Wan Y, Li W, Liu C, Li HF, Dong Z, Zhu K, Jiang S, Shang E, Qian D, Duan J. Targeting intestinal flora and its metabolism to explore the laxative effects of rhubarb. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2022;106:1615-1631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Stompor-Gorący M. The Health Benefits of Emodin, a Natural Anthraquinone Derived from Rhubarb-A Summary Update. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Huang Q, Lu G, Shen HM, Chung MC, Ong CN. Anti-cancer properties of anthraquinones from rhubarb. Med Res Rev. 2007;27:609-630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 399] [Cited by in RCA: 410] [Article Influence: 22.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zhang F, Wu R, Liu Y, Dai S, Xue X, Li Y, Gong X. Nephroprotective and nephrotoxic effects of Rhubarb and their molecular mechanisms. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;160:114297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Pei R, Jiang Y, Lei G, Chen J, Liu M, Liu S. Rhein Derivatives, A Promising Pivot? Mini Rev Med Chem. 2021;21:554-575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zhuang T, Gu X, Zhou N, Ding L, Yang L, Zhou M. Hepatoprotection and hepatotoxicity of Chinese herb Rhubarb (Dahuang): How to properly control the "General (Jiang Jun)" in Chinese medical herb. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;127:110224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wang L. Overview of the pharmacology and clinical application of rhubarb in the treatment of gastric ulcer bleeding. Shijie Zuixin Yixue Xinxi Wenzhai. 2018;18:158-159. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Sanajou D, Ghorbani Haghjo A, Argani H, Aslani S. AGE-RAGE axis blockade in diabetic nephropathy: Current status and future directions. Eur J Pharmacol. 2018;833:158-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 29.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ma X, Ma J, Leng T, Yuan Z, Hu T, Liu Q, Shen T. Advances in oxidative stress in pathogenesis of diabetic kidney disease and efficacy of TCM intervention. Ren Fail. 2023;45:2146512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Perrone A, Giovino A, Benny J, Martinelli F. Advanced Glycation End Products (AGEs): Biochemistry, Signaling, Analytical Methods, and Epigenetic Effects. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020;2020:3818196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 256] [Article Influence: 51.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Khalid M, Petroianu G, Adem A. Advanced Glycation End Products and Diabetes Mellitus: Mechanisms and Perspectives. Biomolecules. 2022;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 380] [Article Influence: 126.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Pérez-Morales RE, Del Pino MD, Valdivielso JM, Ortiz A, Mora-Fernández C, Navarro-González JF. Inflammation in Diabetic Kidney Disease. Nephron. 2019;143:12-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 27.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Tang D, He WJ, Zhang ZT, Shi JJ, Wang X, Gu WT, Chen ZQ, Xu YH, Chen YB, Wang SM. Protective effects of Huang-Lian-Jie-Du Decoction on diabetic nephropathy through regulating AGEs/RAGE/Akt/Nrf2 pathway and metabolic profiling in db/db mice. Phytomedicine. 2022;95:153777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hou B, Qiang G, Zhao Y, Yang X, Chen X, Yan Y, Wang X, Liu C, Zhang L, Du G. Salvianolic Acid A Protects Against Diabetic Nephropathy through Ameliorating Glomerular Endothelial Dysfunction via Inhibiting AGE-RAGE Signaling. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;44:2378-2394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Nasser MW, Ahirwar DK, Ganju RK. RAGE: A novel target for breast cancer growth and metastasis. Oncoscience. 2016;3:52-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Xie J, Méndez JD, Méndez-Valenzuela V, Aguilar-Hernández MM. Cellular signalling of the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE). Cell Signal. 2013;25:2185-2197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 332] [Cited by in RCA: 400] [Article Influence: 33.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Waghela BN, Vaidya FU, Ranjan K, Chhipa AS, Tiwari BS, Pathak C. AGE-RAGE synergy influences programmed cell death signaling to promote cancer. Mol Cell Biochem. 2021;476:585-598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Brady HJ, Gil-Gómez G. Bax. The pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member, Bax. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1998;30:647-650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Sinha SK, Nicholas SB. Pathomechanisms of Diabetic Kidney Disease. J Clin Med. 2023;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |