Published online Mar 15, 2019. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v10.i3.224

Peer-review started: January 27, 2019

First decision: February 19, 2019

Revised: March 6, 2019

Accepted: March 8, 2019

Article in press: March 9, 2019

Published online: March 15, 2019

Processing time: 48 Days and 20.7 Hours

Inadequate health infrastructure and poverty especially in rural areas are the main hindrance in the optimal management of subjects with type 1 diabetes (T1D) in Pakistan.

To observe effectiveness of diabetes care through development of model clinics for subjects with T1D in the province of Sindh Pakistan.

A welfare project with name of “Insulin My Life”, was started in province of Sindh, Pakistan. This was collaborative work of Baqai Institute of Diabetology and Endocrinology, World Diabetes Foundation and Baqai Medical University between February 2010 to February 2013. Under this project thirty-four T1D clinics were established. Electronic database was designed for demographic, biochemical, anthropometric and medical examination. Monthly consultation was part of the standardized diabetes care. All the recruited subjects with T1D were provided free insulins and related materials.

Out of 1428 subjects, 795 (55.7%) were males and 633 (44.3%) were females. Subjects were categorized into ≤ 5 years of age 103 (7.2%), between 6-12 years 323 (22.6%), between 13–18 years 428 (29.7%) and ≥ 19 years of age 574 (40.2%) groups. Glycemic control as assessed by HbA1c was significantly improved (P < 0.0001) at three years follow up as compared to baseline in all age groups. Decreasing trends of mean self-monitoring blood glucose were observed at different meal timings in all age groups. No significant change was found in the frequency of neuropathy, nephropathy and retinopathy during the study period (P > 0.05).

This study gives us long-term longitudinal data of people with T1D in a resource constraint society. With provision of standardized and comprehensive care significant improvement in glycemic control without any change in the frequency of microvascular complications was observed over 3 years.

Core tip: This study adds the three years follow up of subjects with type 1 diabetes (recent) by providing all healthcare related facilities. This study will highlight the impact of integrated and comprehensive care on the glycemic control and complications of diabetes.

- Citation: Ahmedani MY, Fawwad A, Shaheen F, Tahir B, Waris N, Basit A. Optimized health care for subjects with type 1 diabetes in a resource constraint society: A three-year follow-up study from Pakistan. World J Diabetes 2019; 10(3): 224-233

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v10/i3/224.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v10.i3.224

Annually, more than 132600 subjects under 19 years of age have been diagnosed with type 1 diabetes (T1D) globally[1]. It is also estimated that currently around 1106500 subjects (0-19 years) are living with T1D worldwide[1]. Although, there are clear geographic differences in trends but the estimated annual increase in T1D is around 3%[2]. In 2015, according to IDF, more than 7 million cases of diabetes are reported in Pakistan out of which 2% are suffering from T1D[3]. The incidence of T1D in Pakistan has been reported as 1.02 per 100000 per year[4].

Uncontrolled T1D can lead to microvascular and macrovascular complications mostly in young age group posing a challenge for health care professionals[2,5]. Majority of subjects with T1D living in developing countries have minimum or no access to optimal care[2,6] As a result, these subjects are prone to acute and chronic complications of T1D affecting their quality of life[7].

Limited studies are available on acute and chronic complications in people with T1D from Pakistan[8]. A study conducted in the province of Sindh, showed higher rate of complication in subjects with T1D. Authors have reported that every fourth person with T1D is suffering from any one of the chronic complication while 2% subjects with T1D had diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and 21% had history of DKA[9]. Similar trend was noted in smaller scale studies from this region[8,10].

Inadequate health infrastructure and poverty especially in rural areas are the main hindrance in the optimal management of subjects with T1D in Pakistan[11-13]. In Pakistan, 33% people lives with poverty and most of the populations (40%) does not receive basic health services[14]. Health expenses are 0.7%-0.8% of gross domestic product of Pakistan, while 3.5% of total governmental budget. Overall health care system in Pakistan also offers the support for diabetes but subjects with T1D needs specific attention and optimal care[7,14].

The study aims to observe effectiveness of optimal care for subjects with T1D including (free periodic consultations, education, dietary advice, provision of insulin and syringes, glucometers, and assessment of glycemic control through HbA1c 6 monthly) by establishing model clinics throughout the province of Sindh, Pakistan.

A welfare project with name of “Insulin My Life (IML)”, was started in the province of Sindh in between February 2010 to February 2013. This was a collaborative work of Baqai Institute of Diabetology and Endocrinology (BIDE), World Diabetes Foundation and Baqai Medical University. Ethical approval was obtained by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of BIDE with approval/reference number: BIDE/IRB/Prof.Yakoob-IML/02/11/10/025. Subjects with only T1D were included in this study. Informed consent was obtained from above 19 years of age and below 19 years were enrolled after obtaining informed consent from their parents by diabetes educators and physicians.

A total of 34 physicians with post graduate diploma in diabetes and 30 diabetes educators were identified from each district of Sindh. A three days structured training program as per the standard guidelines[15,16] for the management of T1D and prevention of complications was designed for the physicians and for the educators separately.

More than 0.3 million teachers were sensitized about T1D specifically for the identification and management of emergencies in subjects with T1D. A total of 654 community based awareness camps and group sessions were held in the vicinity of identified clinics. In these awareness camps knowledge of self-monitoring blood glucose (SMBG), insulin using techniques, dose regime, optimal targets for glycemic control, adequate diet, physical activity, sick day rule, signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia were provided to subjects with T1D and their family members.

Printed educational material in English, Urdu and regional language (Sindhi) was also provided to subjects with T1DM, their parents and community. Eighteen televisions and 30 radio programmes in local and regional languages were also telecasted as a part of awareness campaign. A dedicated website www.insulinmylife.com was also launched to dessiminate relevant information regarding T1D[17].

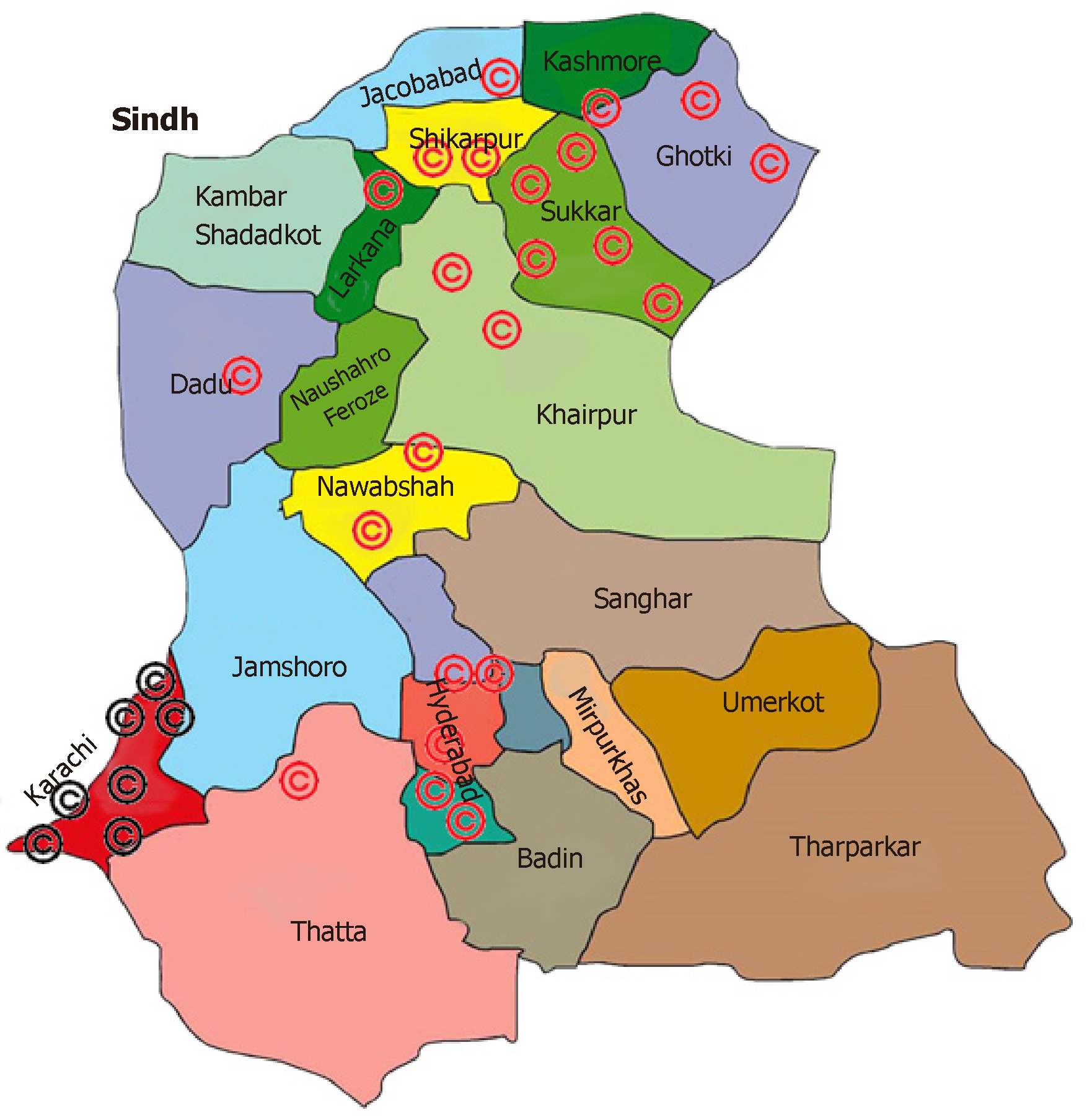

Thirty-four model type 1 diabetic clinics were established at least one in each district of Sindh during the initial phase of the project (Figure 1)[17]. A 24 h telephonic helpline service was made available to all project registrants. Through 24 h helpline service trained diabetes educators in consultation with primary consultant gave advises and sort out day to day problems including dose adjustments, hypo and hyperglycemic management. In case of emergency these registered subjects with diabetes were advised to contact emergency services.

Biochemical parameters include glucose level in fasting, after 2-h of postprandial glucose, HbA1c, proteinuria and urinary ketones. Polyphagia, polyuria, polydipsia, weight loss history, and DKA history which are confirmed if previous records are present were recorded. In suspected cases of DKA, blood pH, HCO3 was done[9].

No single subject had free insulin and blood sugar testing equipment at the start of the study. All registered subjects with T1D were asked to have free of cost consultation with physician, diabetes educators, free coverage for insulin and glucose testing equipment after every six months.

Subjects with other than T1D were excluded from the study. HbA1c, microalbuminuria test and consultation with a dietitian were offered after every 6 months. Free medical supplies including insulin, glucometers, glucose strips, lancets and insulin syringes, SMBG recording booklets were provided to the participants and they were asked to monitor their glucose readings with a record of these readings to be maintained in diaries. All children (less than and equal to 12 years of age) with T1D were referred to pediatrician as and when needed. The Growth chart with growth velocity was also followed throughout the study period.

Glycemic control was assessed by checking FBS and RBS at baseline and end of the study along with fasting HbA1c at baseline and after every 6 mo during 3 years follow up. Glycemic control was also assessed by using SMBG level at different meal timings in all age groups. Those who have HbA1c between 6.5%-8%, 9%–10% and ≥ 10% were considered good, fair and poor control, respectively[15,18].

Vista 20 direct ophthalmoscope was used for fundus examine. Retinopathy was confirmed by normal, microdots, hard exudates, pre-proliferative and proliferative or maculopathy. Protein > 1+ on dipstick (Combur 10, Roche Diagnostics) show nephropathy. Twenty-four hours quantitative analyses of urine for protein and creatinine were done. Neuropathy was known as absent touch or vibratory sensations of the feet. The 10-g monofilament and vibration sensation by 128 Hz tuning fork was used for touch sensation.

Electronic and centralized database was designed to records demographic, biochemical, anthropometric and medical examination.

Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS, version 20) was used for demographic and biochemical data. Continuous data was presented as mean, standard deviation and categorical data as numbers and percentages. Chi-square test was used for comparison of percentages and t test was performed for the mean difference comparison. Statistically significant was considered as P-value < 0.05.

T1D model clinics in the province of Sindh-Pakistan are shown in Figure 1. Out of 1428 subjects 790 (55.3%) were males and 638 (44.7%) were females. Subjects were categorized into four groups according to age as ≤ 5 years of age (n = 103, 7.2%), between 6-12 years (n = 323, 22.6%), between 13–18 years (n = 428, 29.7%) and ≥ 19 years of age (n = 574, 40.2%) groups. Mean age (years) at the time of diagnosis in ≤ 5 years of age was 3.2 (± 1.5) and at the time of recruitment 3.5 (± 1.5), between 6-12 years was 8.3 (± 2.5) and 9.5 (± 1.9), between 13–18 years 13.7 (± 3.6) and 15.6 (± 1.7) and in ≥ 19 years of age groups 22 (± 6.3) and 25.7 (± 5.5), respectively. Duration of diabetes, family history of diabetes, weight, systolic and diastolic blood pressure were noted in all age groups along with serum creatinine at baseline (Table 1).

| Variables | 0-5 yr | 6-12 yr | 13-18 yr | 19 and above |

| n (%) | 103 (7.21) | 323 (22.62) | 428 (29.97) | 574 (40.2) |

| Male | 50 (48.5) | 155 (48) | 251 (58.6) | 334 (58.2) |

| Female | 53 (51.5) | 168 (52) | 177 (41.4) | 240 (41.8) |

| Age at diagnosis (yr) | 3.2 ± 1.5 | 8.3 ± 2.5 | 13.7 ± 3.6 | 22 ± 6.3 |

| Age at recruitment (yr) | 3.5 ± 1.5 | 9.5 ± 1.9 | 15.6 ± 1.7 | 25.7 ± 5.5 |

| Duration of diabetes (yr) | 0.3 ± 0.7 | 1.1 ± 2 | 1.9 ± 3.3 | 3.7 ± 5.4 |

| Family history of diabetes | 37 (35.9) | 131 (40.6) | 199 (46.5) | 276 (48.1) |

| Weight (kg) | 13.90 ± 2.61 | 28.31 ± 13.01 | 42.86 ± 10.64 | 53.11 ± 10.34 |

| Serum Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.64 ± 0.18 | 0.80 ± 0.19 | 0.94 ± 0.43 | 0.92 ± 0.31 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | --- | 153.67 ± 33.06 | 155.63 ± 40.01 | 163.18 ± 28.58 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | --- | 83.25 ± 42.96 | 103.47 ± 73.66 | 94.46 ± 60.24 |

| High density lipoproteins (mg/dL) | --- | 39.48 ± 12.21 | 42.46 ± 11.73 | 41.52 ± 10.45 |

| Low density lipoproteins (mg/dL) | --- | 79.70 ± 26.07 | 86.34 ± 30.67 | 98.94 ± 30.44 |

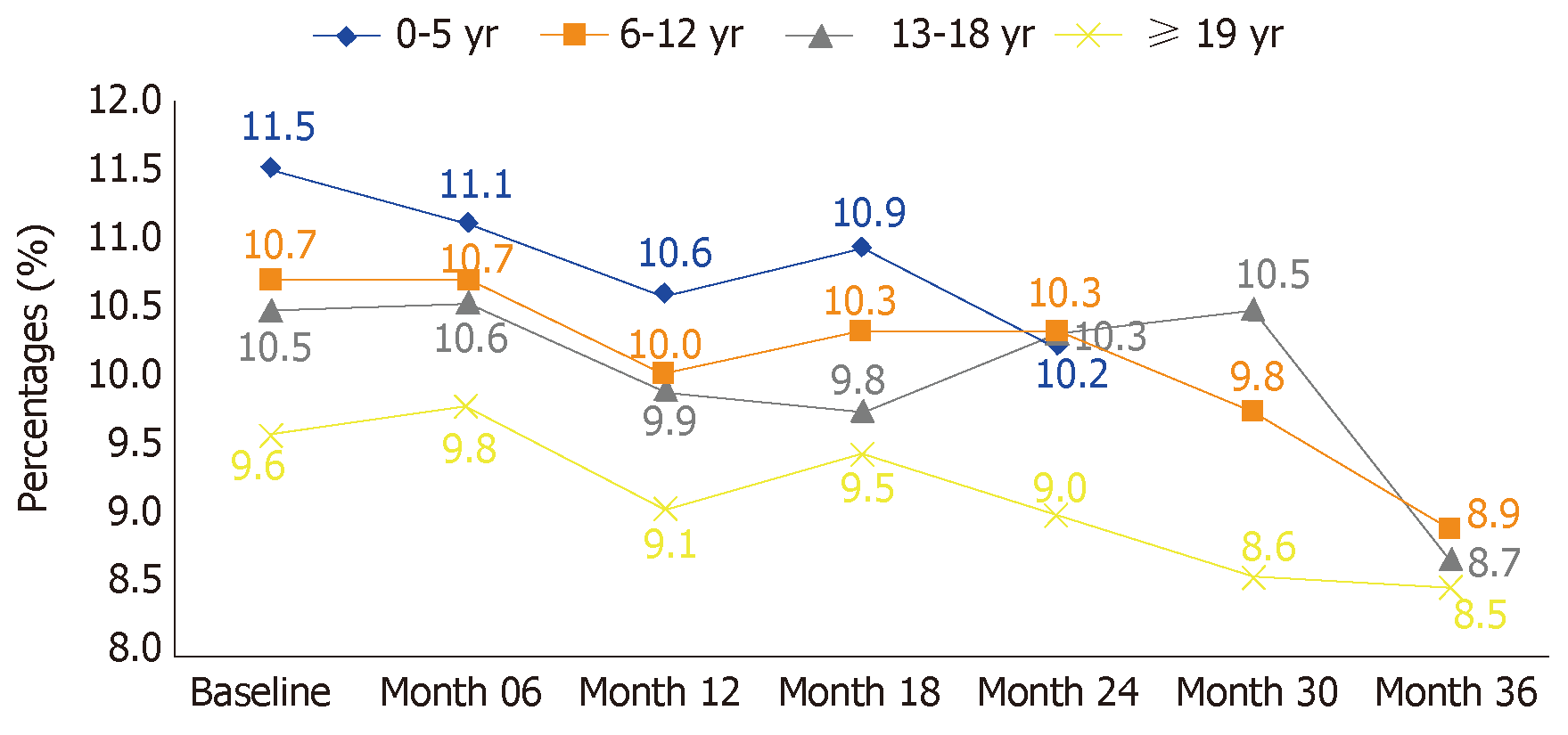

Mean HbA1c at baseline vs end of study in ≤ 5 years of age subjects was (11.5 ± 2.04 vs 10.2 ± 2.12, P = 0.026), between 6-12 years was (10.7 ± 2.28 vs 8.9 ± 2.24, P ≤ 0.0001), between 13–18 years was (10.5 ± 2.76 vs 8.7 ± 2.49, P ≤ 0.0001) and (9.6 ± 2.52 vs 8.5 ± 2.17, P < 0.0001) in ≥ 19 years of age. A significant decrease in HbA1c was observed in all age categories (P < 0.05) (Table 2). The comparison of systolic, diastolic blood pressure along with fasting and random blood glucose were also presented in Table 2. Glycemic control as retrieved by HbA1c was significantly improved at final visit as compared to the baseline in all age groups. At baseline visit good glycemic control was observed in 3.6% subjects which increased to 25.9% at the end of study for ≤ 5 years of age. Similar trend can be seen in age 6-12 years (baseline 13.5% vs end line 36.3%, P < 0.0001), for age 13–18 years (14.7% vs 37.7%, P < 000001) and (26.8% vs 62.1%, P < 0.0001) for ≥ 19 years of age group (Table 3).

| Variables | Age (yr) | ||||

| 0-5 yr | 6-12 yr | 13-18 yr | 19 and above | ||

| HbA1c (%) | Baseline (n = 1428) | 11.5 ± 2.04 | 10.7 ± 2.28 | 10.5 ± 2.76 | 9.6 ± 2.52 |

| End line (n = 516) | 10.2 ± 2.12 | 8.9 ± 2.24 | 8.7 ± 2.49 | 8.5 ± 2.17 | |

| P-value | 0.026 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | Baseline (n = 1428) | 108.3 ± 20.8 | 105.4 ± 14.7 | 106.3 ± 14.7 | 108.2 ± 14.9 |

| End line (n = 1428) | 92.4 ± 10.3 | 99.1 ± 13.3 | 105.3 ± 13.3 | 112.7 ± 14.2 | |

| P-value | 0.001 | 0.0002 | 0.500 | 0.001 | |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | Baseline (n = 1428) | 74.6 ± 11.2 | 72.9 ± 10.6 | 73.7 ± 10.5 | 74.3 ± 10 |

| End line (n = 1428) | 65 ± 6.6 | 66.2 ± 7.7 | 71.3 ± 8.3 | 74.6 ± 8.5 | |

| P-value | 0.001 | 0.0004 | 0.002 | 0.747 | |

| Fasting blood sugar (mg/dL) | Baseline (n = 1428) | 199.2 ± 109.4 | 266.4 ± 118.9 | 282.4 ± 107 | 266.20 ± 112.6 |

| End line (n = 1428) | 77.0 ± 2.64 | 293.86 ± 105.57 | 270.96 ± 104.83 | 252.43 ± 117.13 | |

| P-value | 0.059 | 0.292 | 0.550 | 0.415 | |

| Random Blood Sugar (mg/dl) | Baseline (n = 1428) | 326.2 ± 161.1 | 342.4 ± 149.7 | 360.3 ± 135.4 | 338.9 ± 131 |

| End line (n = 1428) | 522.33 ± 267.54 | 479.24 ± 189.99 | 394.63 ± 171.36 | 354.86 ± 157.43 | |

| P-value | 0.002 | <0.0001 | 0.138 | 0.476 | |

| Age (yr) | ||||||||

| Glycemic category | 0-5 yr | 6-12 yr | 13-18 yr | 19 and above | ||||

| Baselinevisit | Lastvisit | Baselinevisit | Last visit | Baselinevisit | Last visit | Baselinevisit | Last visit | |

| Good glycemic control (HbA1c < 6.5%-8%) | 3.6 | 25.9 | 13.5 | 36.3 | 14.7 | 37.7 | 26.8 | 62.1 |

| Fair glycemic control (HbA1c 9%-10%) | 14.3 | 40.7 | 16.2 | 19.1 | 14.7 | 14 | 26.8 | 12.4 |

| Poor glycemic control (HbA1c ≥ 10%) | 82.1 | 33.3 | 70.3 | 44.5 | 70.7 | 48 | 46.5 | 25.5 |

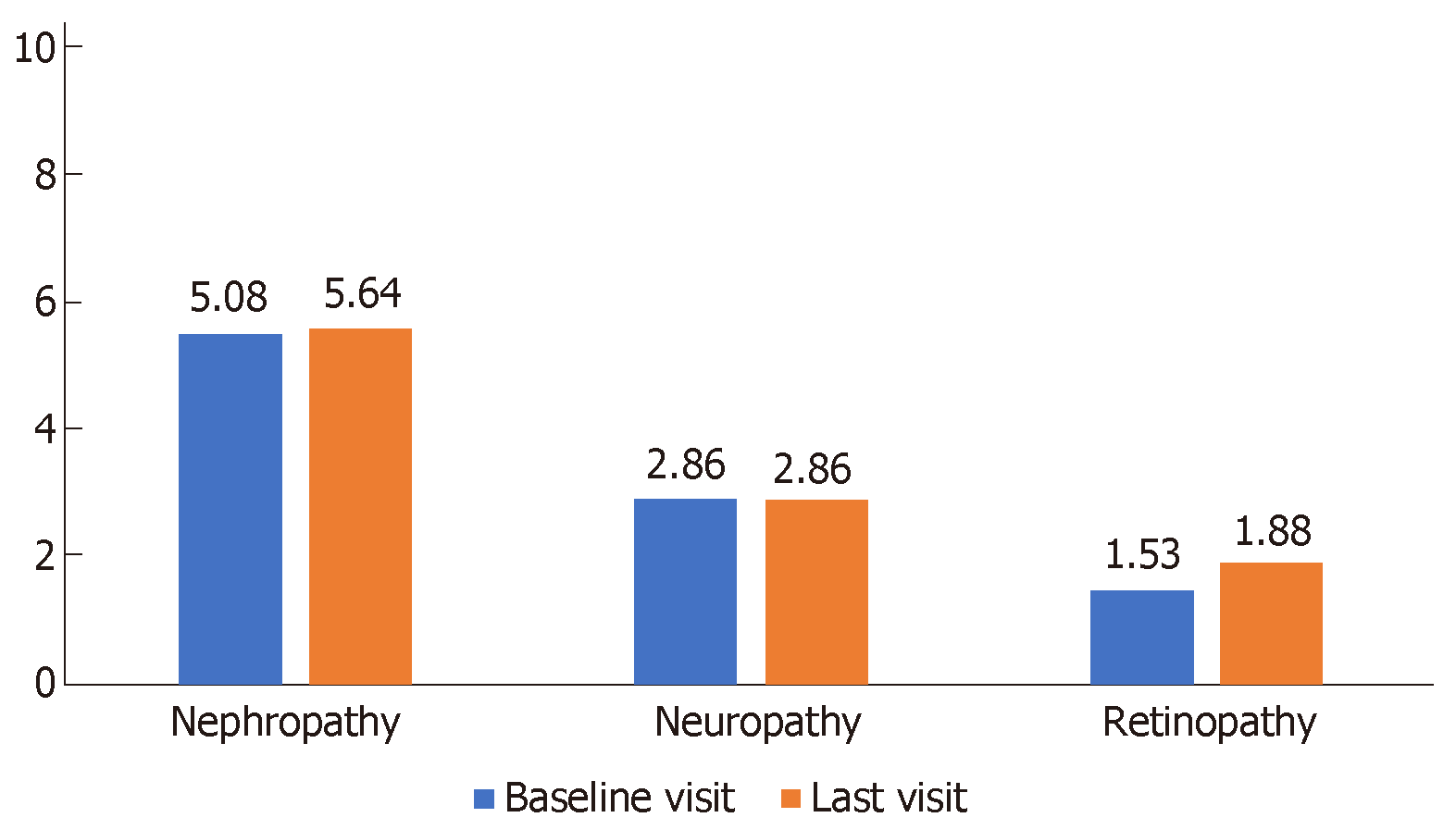

During three years follow up decreasing trends of mean SMBG were also observed at different meal timings in all age groups (Table 3). Comparatively lower mean SMBG values were observed compared to first month during the study period (Table 4). Graphical representation of microvascular complications was shown in Figure 2. The frequency of retinopathy shows a slight increasing (non-significant) trend, while the frequency of nephropathy and neuropathy almost remained the same during the study period. Significant improvement in HbA1c levels was observed in all age groups at end of study period (at 3 years) (Figure 3).

| Timing | Month 1 | Year 1 (month 2-12) | Year 2(month 13-24) | Year 3(month 25-36) |

| Before breakfast | ||||

| 0-5 yr | 213.5 | 202.6 | 184.1 | 150.9 |

| 6-12 yr | 197.3 | 173.6 | 193.1 | 146.2 |

| 13-18 yr | 180.3 | 169.9 | 168.3 | 137.8 |

| 19 and above | 163.2 | 151.5 | 139.6 | 138 |

| After 2 h of breakfast | ||||

| 0-5 yr | 328.5 | 246.9 | 167.7 | 194 |

| 6-12 yr | 215.5 | 209.5 | 203.5 | 190.3 |

| 13-18 yr | 232.5 | 203.5 | 215.5 | 173.8 |

| 19 and above | 200.3 | 178.6 | 166.2 | 184.6 |

| Before lunch | ||||

| 0-5 yr | 248.2 | 265.8 | 132.3 | 140.2 |

| 6-12 yr | 180.1 | 191.2 | 194.3 | 184 |

| 13-18 yr | 200.3 | 189.7 | 192.8 | 148.9 |

| 19 and above | 164 | 160.2 | 147.4 | 151.7 |

| After 2 h of lunch | ||||

| 0-5 yr | 281.6 | 252.2 | 204.7 | 257.5 |

| 6-12 yr | 269.8 | 226.8 | 237.3 | 207.6 |

| 13-18 yr | 246.6 | 230.6 | 237.4 | 194.8 |

| 19 and above | 223.1 | 211.8 | 202.8 | 203.8 |

| Before dinner | ||||

| 0-5 yr | 299.2 | 276 | 216.2 | 239.9 |

| 6-12 yr | 262 | 261.1 | 242.6 | 218.1 |

| 13-18 yr | 255 | 228.4 | 234 | 205.5 |

| 19 and above | 223.6 | 191.8 | 211.4 | 182.1 |

| After 2 h of dinner | ||||

| 0-5 yr | 297.3 | 254.3 | 196.8 | 239.8 |

| 6-12 yr | 239.3 | 247.8 | 244.7 | 192.5 |

| 13-18 yr | 240.1 | 219.2 | 213.7 | 179.8 |

| 19 and above | 217.4 | 195.9 | 212.1 | 180.7 |

| Before sleeping | ||||

| 0-5 yr | 273.3 | 254.9 | 212.5 | 214.7 |

| 6-12 yr | 230.7 | 230.6 | 181.1 | 211.3 |

| 13-18 yr | 195 | 223.3 | 218.8 | 165.7 |

| 19 and above | 167.3 | 167.9 | 196.4 | 195 |

In this observational study, a three year follow up of people with T1D registered under project of IML in the province of Sindh Pakistan. Significant improvement in the glycemic control was noted with provision of comprehensive care, awareness and treatment free of cost.

Though it is difficult to achieve optimum glycemic control among adolescents, regardless the type of diabetes[19], what we have observed that with proper care fewer people remained in the poor glycemic category and many people achieved fair to good control (Table 2). This has been shown by Diabetes Patient Verlaufsdokumentation (DPV) registry also that healthy outcomes can be achieved in individuals with T1D when provided with optimized and personalized care[20]. Good glycemic control not only important for decreasing the morbidity, but it can decrease diabetes related mortality rate as well as shown by Nordwall M related DM registry[21,22]. On the other hand, without proper access to standardized care people with T1D suffer from adverse results even at an earlier age[23]. In our study, over 3 years, people with T1D in each age category showed downward trend of HbA1c and this decline was statistically significant.

With provision of free glucostrips and glucometers it was made possible for study registered participants to check blood glucose at least 2 times/d. However, the annual cost per participant which include consultation fee, lab diagnosis, glucometers, insulins, strips, lancets and syringes, etc. was 61000pkr (436USD), per month 5083pkr (36USD) and per day 169pkr (1.2USD). SMBG profile of our cohort also showed downward trend at different mealtimes and this proves that by continuous education and pursuing its effectiveness enhances the motivation of subjects and their families to achieve better glycemic control. Study from Bulgarian suggests that due to families’ devotion to diabetes control, children under six years achieved good glycemic control[24]. Glycemic control with chronic complications was clearly shown by landmark study that is in Diabetes Control and Complication Trial (DCCT)[25,26]. On the contrary association between poor glycemic control and increase risk of chronic complication was shown by several studies[26].

In study from Southeast Sweden, prolonged uncontrolled HbA1c was closely associated with the development of severe complications in individuals with T1D[22]. Another observational, population based study from DPV registry indicates that poor HbA1c was found to be a powerful biomarker for the development of retinopathy, nephropathy and neuropathy in patients with T1D[27]. Time to onset of complications was also influenced by HbA1c as in the primary prevention cohort of DCCT[22]. However, in our study rate of complication including nephropathy, and neuropathy remained the same throughout the study period through there was non-significant rise in frequency of retinopathy.

This study with best of our knowledge, concludes that it is first of its kind from Pakistan, giving us long-term longitudinal data of patients with T1D in a resource constraint society. With provision of standardized and comprehensive care significant improvement in glycemic control without any change in the frequency of microvascular complications was observed over 3 years.

In a resource constraint society like Pakistan, there is lack of an infrastructure for current study to provide health care system in a proper way. But, with available resources such kind of data was considered as the best available option. All the study participants during the study duration were coming to their respective medical centers for the required care. However, in remote areas the follow-up HbA1c was not completely available. This study helps us to know more about T1D in Pakistan than ever before, but much is still to be learned. This study need to be replicated at Nationwide level.

Inadequate health infrastructure and poverty especially in rural areas are the main hindrance in the optimal management of subjects with type 1 diabetes (T1D) in Pakistan.

The current study with lack of an infrastructure provides health care system in a proper way with available resources, to evaluate patient centered outcomes in the measurement of progression and treatment. Such kind of data was considered as the best available option.

The objective of this study is to observe the effectiveness of diabetes care through development of model clinics for subjects with T1D in the province of Sindh Pakistan.

In this welfare project “Insulin My Life (IML)”, subjects with only T1D were included. Thirty-four model T1D clinic were established and total of 654 community based awareness camps and group sessions were held. All registered subjects with T1D were asked to have free of cost consultation with physician, diabetes educators, free coverage for insulin and glucose testing equipment after every six months. Glycemic control was assessed by checking FBS and RBS at baseline and end of the study along with fasting HbA1c at baseline and after every 6 mo during 3 years follow up. Glycemic control was also assessed by using self-monitoring blood glucose level (SMBG) at different meal timings in all age groups.

Out of 1428 subjects 790 (55.3%) were males and 638 (44.7%) were females. Glycemic control as retrieved by HbA1c was significantly improved at final visit as compared to the baseline in all age groups. At baseline visit good glycemic control was observed in 3.6% subjects which increased to 25.9% at the end of study for ≤ 5 years of age. Similar trend can be seen in age 6-12 years, 13–18 years, and ≥ 19 years of age group. Comparatively lower mean SMBG values were observed compared to first month during the study period.

With provision of standardized and comprehensive care significant improvement in glycemic control without any change in the frequency of microvascular complications was observed over 3 years.

This study helps us to know more about T1D in Pakistan than ever before, but much is still to be learned. This study need to be replicated at Nationwide level.

We acknowledge the support of “Insulin My Life” (IML) project, a collaborative project of World Diabetes Foundation (WDF), Life for a Child program (LFAC) and Baqai Institute of Diabetology and Endocrinology (BIDE). We also grateful to following doctors of type 1 model clinics for their help in recruiting and care in the IML project; Dr. Abdul Rasheed Joyo (Khairpur), Dr. Abdullah Memon (Sukkar), Dr. Aejaz Solangi (Khairpur), Dr. Ahsan Siddiqui (Gharo, Sehwan and Karachi), Dr. Ameer Memon (khairpur), Dr. Asif Brohi (Nawabshah), Dr. Fareed Uddin (Karachi), Dr. Farhan Baloch (Sukkar and Shikarpur), Dr. Fateh Dero (Hyderabad), Dr. Irshad Ahmed (Hyderabad), Dr. Kashif (Nawabshah), Dr. Merajuddin Nizami (Hyderabad), Dr. Najma Samejo (Tandojam), Dr. Nazeer Khokar (Khairpur), Dr. Nazeer Soomro (Jacobabad), Dr. Pawan Kumar (Kashmoor and Larkana), Dr. Riasat Ali Khan (Karachi), Dr. Riaz Ahmed (Tharparkar), Dr. Muhammad Saif Ulhaque (Karachi), Dr. Sanober (Karachi), Dr. Shahid (Nosheroferoz), Dr. Shahjahan Mangi (Shikarpur), Dr. Umeet Kumar (Ghotki), Dr. Veru Mal (Karachi and Mirpurkhas), Dr. Zahoor Shaikh (Dadu), Dr. Muhammad Irfan (Shahdahpur), Dr. Zahid Miyan (Karachi), Dr. Awn Bin Zafar (Karachi), Dr. Farhatullah Khan (Karachi). We would also like to thank Dr. Maqsood Mohiuddin and Mr. Iqbal Hussain (Project Coordinators), Mrs. Afshan Siddiqui and Miss. Raheela Naseem (Clinical Coordinators) and Mrs. Rubina Sabir and Mr. Fawwad Ahmed (Laboratory and Pharmacy Managers) for their support. Prof. Muhammad Yakoob Ahmedani and Dr. Asher Fawwad, is a guarantor and undertakes the full responsibility for all contents of the article submitted for publication.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Endocrinology and metabolism

Country of origin: Pakistan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Fatima SS, Serhiyenko VA, Tomkin GHH S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | International Diabetes Federation. IDF diabetes atlas - 8th Edition. Atlas. 2017; Available from: http://diabetesatlas.org/resources/2017-atlas.html. |

| 2. | Patterson C, Guariguata L, Dahlquist G, Soltész G, Ogle G, Silink M. Diabetes in the young - a global view and worldwide estimates of numbers of children with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;103:161-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 273] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | International Diabetes Federation, Pakistan. Available from: https://www.idf.org/our-network/regions-members. |

| 4. | DIAMOND Project Group. Incidence and trends of childhood Type 1 diabetes worldwide 1990-1999. Diabet Med. 2006;23:857-866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 826] [Cited by in RCA: 822] [Article Influence: 43.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Basit A, Khan A, Khan RA. BRIGHT Guidelines on Self-Monitoring of Blood Glucose. Pak J Med Sci. 2014;30:1150-1155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | World Health Organization. Global Report on Diabetes, 2016. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/204871/1/9789241565257_eng.pdf. |

| 7. | Fawwad A, Ahmedani MY, Basit A. Integrated and comprehensive care of subjects with type 1 diabetes in a resource poor environment- “insulin my life (IML)” project. Int J Adv Res. 2017;5:1339-1342. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rashid MO, Sheikh A, Salam A, Farooq S, Kiran Z, Islam N. Diabetic ketoacidosis characteristics and differences In type 1 versus type 2 diabetes patients. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2017;29:398-402. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Shera AS, Miyan Z, Basit A, Maqsood A, Ahmadani MY, Fawwad A, Riaz M. Trends of type 1 diabetes in Karachi, Pakistan. Pediatr Diabetes. 2008;9:401-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Syed M, Khawaja FB, Saleem T, Khalid U, Rashid A, Humayun KN. Clinical profile and outcomes of paediatric patients with diabetic ketoacidosis at a tertiary care hospital in Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2011;61:1082-1087. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Ahmedani MY, Fawwad A, Basit A, Nawaz A. Efficacy of Dongsulin (rDNA human insulin) in a normal clinical practice setting. Pak J Biol Sci. 2008;11:2356-2359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Regional Health Systems Observatory, World Health Organization. Health system profile of Pakistan. 2007; Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s17305e/s17305e.pdf. |

| 13. | Kurji Z, Premani ZS, Mithani Y. Analysis Of The Health Care System Of Pakistan: Lessons Learnt And Way Forward. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2016;28:601-604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Basit A, Riaz M, Fawwad A. Improving diabetes care in developing countries: the example of Pakistan. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2015;107:224-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:977-986. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17510] [Cited by in RCA: 16280] [Article Influence: 508.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 16. | Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (EDIC). Design, implementation, and preliminary results of a long-term follow-up of the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial cohort. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:99-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 457] [Cited by in RCA: 484] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Insulin my life project. Available from: http://www.insulinmylife.com/. |

| 18. | You WP, Henneberg M. Type 1 diabetes prevalence increasing globally and regionally: the role of natural selection and life expectancy at birth. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2016;4:e000161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Dabelea D, Stafford JM, Mayer-Davis EJ, D'Agostino R, Dolan L, Imperatore G, Linder B, Lawrence JM, Marcovina SM, Mottl AK, Black MH, Pop-Busui R, Saydah S, Hamman RF, Pihoker C; SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Research Group. Association of Type 1 Diabetes vs Type 2 Diabetes Diagnosed During Childhood and Adolescence With Complications During Teenage Years and Young Adulthood. JAMA. 2017;317:825-835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 524] [Cited by in RCA: 477] [Article Influence: 59.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | De Meyts P. The Insulin Receptor and Its Signal Transduction Network. Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, editors. Endotext, South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc 2000; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK378978/?report=reader. |

| 21. | Morgan E, Black CR, Abid N, Cardwell CR, McCance DR, Patterson CC. Mortality in type 1 diabetes diagnosed in childhood in Northern Ireland during 1989-2012: A population-based cohort study. Pediatr Diabetes. 2018;19:166-170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Nordwall M, Abrahamsson M, Dhir M, Fredrikson M, Ludvigsson J, Arnqvist HJ. Impact of HbA1c, followed from onset of type 1 diabetes, on the development of severe retinopathy and nephropathy: the VISS Study (Vascular Diabetic Complications in Southeast Sweden). Diabetes Care. 2015;38:308-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Viswanathan V. Preventing microvascular complications in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2015;19:S36-S38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Archinkova M, Konstantinova M, Savova R, Iotova V, Petrova C, Kaleva N, Koprivarova K, Popova G, Koleva R, Boyadzhiev V, Mladenov W. Glycemic control in type 1 diabetes mellitus among Bulgarian children and adolescents: the results from the first and the second national examination of HbA1c. Biotechnol Biotec Eq. 2017;31:1198-1203. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Jendle J, Ericsson Å, Hunt B, Valentine WJ, Pollock RF. Achieving Good Glycemic Control Early After Onset of Diabetes: A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis in Patients with Type 1 Diabetes in Sweden. Diabetes Ther. 2018;9:87-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Nathan DM; DCCT/EDIC Research Group. The diabetes control and complications trial/epidemiology of diabetes interventions and complications study at 30 years: overview. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:9-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 866] [Cited by in RCA: 1021] [Article Influence: 92.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Reinauer C, Reinehr T, Baechle C, Karges B, Seyfarth J, Foertsch K, Schebek M, Woelfle J, Roden M, Holl RW, Rosenbauer J, Meissner T. Relationship of Serum Fetuin A with Metabolic and Clinical Parameters in German Children and Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes. Horm Res Paediatr. 2018;89:73-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |