Published online Sep 16, 2017. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v9.i9.480

Peer-review started: February 14, 2017

First decision: March 22, 2017

Revised: April 19, 2017

Accepted: May 22, 2017

Article in press: May 24, 2017

Published online: September 16, 2017

Processing time: 212 Days and 0.9 Hours

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of liquid nitrogen cryotherapy as a primary or rescue treatment for BE, with and without dysplasia, or intramucosal adenocarcinoma (IMC).

This was a retrospective, single-center study carried out in a tertiary care center including 45 patients with BE who was treatment-naïve or who had persistent intestinal metaplasia (IM), dysplasia, or IMC despite prior therapy. Barrett’s mucosa was resected via EMR when clinically appropriate, then patients underwent cryotherapy until eradication or until deemed to have failed treatment. Surveillance biopsies were taken at standard intervals.

From 2010 through 2014, 33 patients were studied regarding the efficacy of cryotherapy. Overall, 29 patients (88%) responded to cryotherapy, with 84% having complete regression of all dysplasia and cancer. Complete eradication of cancer and dysplasia was seen in 75% of subjects with IMC; the remaining two subjects did not respond to cryotherapy. Following cryotherapy, 15 patients with high-grade dysplasia (HGD) had 30% complete regression, 50% IM, and 7% low-grade dysplasia (LGD); one subject had persistent HGD. Complete eradication of dysplasia occurred in all 5 patients with LGD. In 5 patients with IM, complete regression occurred in 4, and IM persisted in one. In 136 cryotherapy sessions amongst 45 patients, adverse events included chest pain (1%), stricture (4%), and one gastrointestinal bleed in a patient on dual antiplatelet therapy who had previously undergone EMR.

Cryotherapy is an efficacious and safe treatment modality for Barrett’s esophagus with and without dysplasia or intramucosal adenocarcinoma.

Core tip: Liquid nitrogen based cryotherapy is efficacious as a treatment modality for Barrett’s esophagus, especially dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus, either as a first or second line therapy.

- Citation: Suchniak-Mussari K, Dye CE, Moyer MT, Mathew A, McGarrity TJ, Gagliardi EM, Maranki JL, Levenick JM. Efficacy and safety of liquid nitrogen cryotherapy for treatment of Barrett’s esophagus. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2017; 9(9): 480-485

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v9/i9/480.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v9.i9.480

Approximately 17000 people are diagnosed with, and 15600 die of, esophageal cancer each year in the United States[1]. The incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma has increased greatly over the past several decades, and Barrett’s esophagus is a known risk factor for and the sole precursor lesion to esophageal adenocarcinoma[2]. Barrett’s without dysplasia has an increased esophageal cancer risk of approximately 0.3% per year[2]. High-grade dysplasia progresses to adenocarcinoma at a rate as high as 10% per year[2,3].

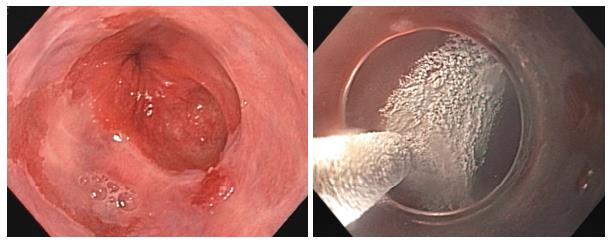

Several endoscopic ablative modalities are available for the treatment of Barrett’s esophagus as alternatives to esophagectomy including cryotherapy, argon plasma coagulation (APC), photodynamic therapy, and radiofrequency ablation (RFA). These therapies are often times used in conjunction with endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) to improve efficacy, especially in long-segment BE[4]. Liquid nitrogen cryotherapy is a noncontact ablation therapy with ease of use compared to other endoscopic modalities[5]. It works via a low-pressure spray of liquid nitrogen that freezes tissue at -196 °C (Figure 1)[6]. Its major advantage is the ability to spray large areas without contact, whereas other therapies require precise contact between the probe and esophageal mucosa[7]. This makes it particularly useful for lesions at the gastroesophageal junction and in cases of complex esophageal anatomy including large hiatal hernias[7].

Current studies regarding the efficacy of cryotherapy are limited by small sample sizes and short observation times; therefore, more data is required so that findings can be compiled into meta-analyses with large numbers of subjects observed over extended periods of time after completion of treatment. Currently available studies have also demonstrated an excellent safety profile with a low risk of adverse events[5,8-13], therefore conferring a unique clinical advantage. The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety data for liquid nitrogen cryotherapy as primary or rescue treatment of Barrett’s esophagus with intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and intramucosal adenocarcinoma at our institution.

This was a retrospective, institutional review board-approved study of a Barrett’s esophagus database at an academic tertiary referral center (Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, Hershey, Pennsylvania) and included all patients that underwent liquid nitrogen cryotherapy for the treatment of Barrett’s esophagus at our institution from January 2010 through December 2014.

Inclusion criteria were adult patients that underwent liquid nitrogen cryotherapy for biopsy-proven Barrett’s esophagus of any length including intestinal metaplasia (IM), low-grade dysplasia (LGD), high-grade dysplasia (HGD), and intramucosal adenocarcinoma (IMC). Endoscopic cryotherapy was offered to appropriate patients on a case-by-case basis both as primary and/or rescue therapy after discussion of the risks and benefits. All patients with intramucosal adenocarcinoma or confirmed high-grade dysplasia on pathology underwent endoscopic ultrasound to rule out nodal or local metastatic disease. Patients who did not follow-up for surveillance biopsies after treatment were included only in the data evaluating for adverse events.

Patients were excluded from the study if they were treated with other endoscopic ablative modalities during the study period, if adenocarcinoma extended beyond the muscularis mucosa, or if evidence of metastatic disease was present.

The database was reviewed in 2015 after the study endpoint. The study was reviewed and approved by the Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center Institutional Review Board (IRB #00002498). Informed consent requirement was waived given the retrospective nature of the study.

All patients underwent sedated, outpatient, high resolution endoscopy, performed by several experienced therapeutic endoscopists, and mucosal biopsies were obtained if indicated. Patients with intramucosal adenocarcinoma or high-grade dysplasia underwent endoscopic ultrasound to exclude metastatic or nodal disease; suspicious lymph nodes were sampled to help reassure against occult invasive disease. Endoscopic mucosal resection was performed when nodular Barrett’s was encountered prior to initiation of cryotherapy or during the cryotherapy session after cryoablation was complete. The primary goal of cryotherapy was complete regression or downgrading of intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and cancer.

The truFreeze® spray cryotherapy system (CSA Medical Inc., Baltimore, Maryland, United States) was used to deliver liquid nitrogen to visible columnar mucosa and the gastroesophageal junction for two cycles of 20 s bursts with observation for adequate freeze and thaw. The timing for dosing was started when ice formation was detected on the treated mucosa. Decompression via a separate catheter was ensured. Multiple treatments were performed based on endoscopic findings and the length of the Barrett’s segments. Patients returned for additional cryotherapy sessions until there was endoscopic and pathologic evidence of complete eradication of Barrett’s esophagus or until treatment was deemed to have failed, defined as lack of responsiveness to therapy confirmed by endoscopy and pathology. Mucosal biopsies were obtained prior to the onset of therapy every 1cm in four quadrants as well as targeted biopsies for areas of concern. Surveillance biopsies using the same technique were at the discretion of the treating endoscopist during treatment and were performed after complete eradication of visible Barrett’s in the entire pre-treatment segment at 3, 6, and 12 mo following completion of therapy.

Adverse events during and immediately after the procedure were recorded. Patient charts were reviewed to determine if patients experienced any adverse effects thereafter, and esophageal stricture formation was noted on the subsequent follow-up endoscopy.

Patients underwent surveillance biopsies at the end of cryotherapy sessions and/or returned for endoscopies with biopsies approximately 3 mo after completion of treatments. Biopsies were taken from visible lesions, if present, and random four-quadrant biopsies were obtained at visualized columnar and neosquamous epithelium and/or at the gastroesophageal junction every centimeter through the extent of the maximal initial extent of Barrett’s.

Biopsy specimens were fixed in formalin and reviewed by experienced gastrointestinal pathologists for the presence of intestinal metaplasia with goblet cells, dysplasia, and adenocarcinoma using a standard classification system. Pathologists were provided with the clinical history and procedural information.

Cryotherapy treatment failure was defined as lack of response to therapy, demonstrated by persistence of the previously-diagnosed intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, or cancer, or progression to worsening dysplasia or cancer. In such cases, EMR or ESD (endoscopic submucosal dissection) was performed to resect localized areas and lesions if appropriate and feasible. Subsequent treatment decisions were made on an individualized patient basis after discussing alternative options with patients including esophagectomy in surgical candidates vs other ablative modalities.

For analysis regarding the efficacy of cryotherapy, the primary endpoint of the study was endoscopic and pathologic improvement in baseline cancer, dysplasia, or intestinal metaplasia, as observed on subsequent surveillance biopsies obtained during the study period. The response rate for eradication of all intestinal metaplasia was also calculated.

For analysis regarding the safety of cryotherapy, the incidence of adverse events, including stricture formation, chest pain, perforation, and bleeding were recorded. This data additionally included patients that were not included in the efficacy analysis due to lack of follow-up surveillance data.

Descriptive statistics including proportions, mean, standard deviation, and median were calculated. Treatment response rates were calculated based on all data available at the end of the study period. All statistical analyses were performed using the GraphPad Software (http://graphpad.com/quickcalcs/).

From January 2010 through December 2014, a total of 45 subjects that underwent cryotherapy at our institution met inclusion criteria for the study. Of these, 33 patients had sufficient surveillance (at least one subsequent endoscopy with biopsies at our institution) to be included in the efficacy data. Characteristics of the entire cohort and the subset evaluated for efficacy are detailed in Table 1. The two groups were similar with respect to age, gender, Barrett’s segment length, and proportions of baseline intestinal metaplasia, low-grade dysplasia, high-grade dysplasia, and intramucosal adenocarcinoma. The study included 45 subjects with a mean age of 66 ± 8.7 (range 47-87) years old, 71% male and 29% female.

| Patients analyzed for efficacy n = 33 | Entire cohort n = 45 | |

| Age, mean ± SD, yr | 66 ± 8.7 (range 47-80) | 66 ± 8.7 (range 47-87) |

| Age > 65 yr | 17 (52) | 22 (49) |

| Male gender | 21 (64) | 32 (71) |

| Barrett’s length, mean ± SD, in cm | 3.3 ± 2.1 (range 0.8-7) | 3.4 ± 2.2 (range 0.8-8) |

| Short segment (≤ 3 cm) | 58% | 56% |

| Long segment (4-10 cm) | 42% | 44% |

| History of ablative therapy | 6 (18) | 12 (27) |

| IM at baseline | 5 (15) | 7 (16) |

| LGD at baseline | 5 (15) | 7 (16) |

| HGD at baseline | 15 (45) | 19 (42) |

| IMC at baseline | 8 (24) | 12 (27) |

| Years observed, mean ± SD, yr | 2.3 ± 1.1 yr (range 1-4) | Entire study duration (4 yr) |

The 33-patient subset had a mean age of 66 ± 8.7 (range 47-80) years old, 64% male and 36% female. Fifty-eight percent of patients in this group had short segment Barrett’s esophagus (≤ 3 cm) and 42% had long segment (3-8 cm), with a mean length of 3.3 ± 2.1 cm (range 0.8-8 cm) in the entire group. Of this subset, 27% had previously undergone another type of endoscopic ablative therapy, including radiofrequency ablation (RFA) or photodynamic therapy (PDT). Of the group with intramucosal cancer, two subjects had previously undergone RFA with treatment failure. All patients in this group underwent EMR prior to or at initiation of cryotherapy. Amongst the patients with high-grade dysplasia, four had previously undergone other endoscopic ablative modalities. Seven of the patients in this group underwent EMR prior to or at initiation of cryotherapy. In the group with low-grade dysplasia, two had previously undergone RFA. Amongst the patients with intestinal metaplasia without dysplasia or cancer, two had previously undergone RFA. The median number of cryotherapy sessions was two, with a range of one to nine sessions per patient.

Amongst all subjects, 29 patients (88%) demonstrated a response to cryotherapy, defined by downgrading of the baseline pathology. Overall, 85% of treated patients demonstrated complete response, defined as eradication of all dysplasia and/or cancer. Of 33 patients, 16 showed complete regression to normal epithelium without residual cancer, dysplasia, or intestinal metaplasia. Results are illustrated in Table 2.

| Pathology after cryotherapy treatments | ||||||

| Baseline Pathology | Complete regression | IM | LGD | HGD | IMC | Total |

| IM | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| LGD | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| HGD | 5 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 15 |

| IMC | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 |

Complete eradication of cancer and dysplasia was seen in six of eight subjects (75%) with intramucosal adenocarcinoma after endoscopic mucosal resection of focal nodules and cryotherapy. The remaining subjects, who had long-segment BE, did not respond to cryotherapy and eventually proceeded with alternative therapy. Of 15 patients with high-grade dysplasia, 7% had low-grade dysplasia, 50% had intestinal metaplasia, and 30% had complete regression to normal epithelium at follow-up. One subject maintained high-grade dysplasia and was subsequently transitioned to RFA. Eradication of dysplasia was seen in all five patients with low-grade dysplasia. Three of these five patients (60%) demonstrated complete regression to normal epithelium, and the remaining two patients (40%) had intestinal metaplasia on subsequent surveillance biopsies. Of the five patients with intestinal metaplasia without dysplasia, complete regression occurred in four (80%), and intestinal metaplasia persisted in one (20%).

Overall surveillance time for the entire 33-patient cohort was 2.3 ± 1.1 years (range 1-4 years) from the time of the initial treatment.

For all 45 patients that underwent cryotherapy during the study period, the overall rate of adverse events was 6.6% amongst 136 total sessions of cryotherapy. Reported adverse events included two episodes of transient chest pain (1%), five strictures (4%), and one gastrointestinal bleed (1%). There were no reported occurrences of post-procedural perforation or fever. The gastrointestinal bleed occurred in a patient on dual antiplatelet therapy who had undergone EMR prior to the cryotherapy session; a stricture also occurred in the same patient. This patient presented to an outside hospital eleven days after the cryotherapy treatment with hematemesis, and an EGD revealed esophageal ulcerations and a visible bleeding vessel that required epinephrine injection, cauterization, and clipping to achieve hemostasis.

One patient that developed a stricture had previously undergone RFA, ultimately with treatment failure. Two of the strictures occurred in the same patient. One of the two episodes of transient chest pain was in a patient that had previously undergone mediastinal radiation. Overall, 5 of the 8 patients that developed adverse events had long-segment BE.

Current data shows cryotherapy-induced eradication of high-grade dysplasia in 87%-95% of patients and complete eradication of intestinal metaplasia in 57%-96%[9,14-16]. Additionally, in early-stage esophageal cancer, cryotherapy has been shown to eliminate mucosal cancer in 75%[10-14], including as rescue therapy in patients who have failed other modalities[17].

In 2005, Johnston et al[8] reported a single-center study of cryotherapy in 11 patients with metaplasia and/or dysplasia; of the nine patients that completed the study, all had eradication of metaplasia and dysplasia at six months. Therapy was well tolerated with no reports of severe chest pain, strictures, or perforation[13,18]. Canto et al[9] (2008) subsequently reported a single-center study of 33 subjects with high-grade dysplasia or intramucosal carcinoma who had previously failed EMR and/or photodynamic therapy. There was a preliminary 72% reduction in Barrett’s esophagus after a mean of three treatments. Again, therapy was well-tolerated without any chest pain, perforation, or strictures[13,19].

In 2009, Dumot et al[10] presented a single-center study of cryotherapy in 30 high-risk patients with HGD and/or intramucosal carcinoma; 90% of subjects had downgrading of pathology stage after cryotherapy. Median follow-up time was one year. Three (10%) subjects reported severe chest pain and three (10%) had strictures requiring dilation; one gastric perforation developed in a patient with Marfan’s syndrome[13,20].

Greenwald et al[6] (2010) later conducted a four-center study in which 77 subjects with metaplasia, low-grade dysplasia (LGD), HGD, intramucosal carcinoma, invasive carcinoma, or severe squamous dysplasia were treated with cryotherapy (323 total treatments). Ninety-four percent of 17 patients with HGD had complete eradication, 88% had eradication of dysplasia, and 53% had eradication of intestinal metaplasia after cryotherapy. Complications included strictures requiring dilation in three patients and moderate to severe chest discomfort in 3.7%[8,13].

Few studies have followed biopsy surveillance for patients with Barrett’s esophagus with dysplasia and intramucosal adenocarcinoma for greater than one year. Overall, our institutional data demonstrated that the use of liquid nitrogen cryotherapy is efficacious and safe as primary or rescue treatment for Barrett’s esophagus, including in patients with dysplasia and intramucosal adenocarcinoma. Response rates were 88%, with complete eradication of all dysplasia and cancer in 84% of patients, including most subjects with baseline pathology showing high-grade dysplasia and/or intramucosal adenocarcinoma. More data regarding the safety and effectiveness of liquid nitrogen cryotherapy with extended observation times would be useful, and analysis of large sample sizes (i.e., by meta-analysis) is needed.

Several modalities exist to try and treat Barrett’s esophagus, especially dysplastic Barrett’s prior to progression into esophageal adenocarcinoma.

The primary two modalities are radiofrequency ablation and endoscopic mucosal resection. Spray cryotherapy is another ablation technique with limited long term efficacy described in the literature.

These results further clarify and define long term efficacy of spray liquid nitrogen cryotherapy for treatment of Barrett’s esophagus including long-term follow-up in a large cohort. Liquid nitrogen cryotherapy is an efficacious first or second line therapy for the treatment of dysplastic and even non-dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus.

This is a single center retrospective study on effectiveness of liquid nitrogen cryotherapy in the treatment of Barrett’s esophagus. The authors admit the clinical usefulness of this technique.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Dobrucali AM, Elpek GO, Iijima K S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9172] [Cited by in RCA: 9958] [Article Influence: 995.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Shaheen NJ, Richter JE. Barrett’s oesophagus. Lancet. 2009;373:850-861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 240] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Azarm A, Lukolic I, Shukla M, Concha-Parra R, Gress F. Endoscopic management of Barrett’s esophagus: advances in endoscopic techniques. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:3055-3064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Greenwald BD, Lightdale CJ, Abrams JA, Horwhat JD, Chuttani R, Komanduri S, Upton MP, Appelman HD, Shields HM, Shaheen NJ. Barrett’s esophagus: endoscopic treatments II. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1232:156-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chen AM, Pasricha PJ. Cryotherapy for Barrett’s esophagus: Who, how, and why? Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2011;21:111-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Greenwald BD, Dumot JA, Horwhat JD, Lightdale CJ, Abrams JA. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of endoscopic low-pressure liquid nitrogen spray cryotherapy in the esophagus. Dis Esophagus. 2010;23:13-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Greenwald BD, Dumot JA. Cryotherapy for Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal cancer. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2011;27:363-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Johnston MH, Eastone JA, Horwhat JD, Cartledge J, Mathews JS, Foggy JR. Cryoablation of Barrett’s esophagus: a pilot study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:842-848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Canto MI, Gorospe EC, Shin EJ, Dunbar KB, Montgomery EA, Okolo P. Carbon dioxide (CO2) cyotherapy is a safe and effective treatment of Barrett’s esophagus (BE) with HGD/intramucosal carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:AB341. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Dumot JA, Vargo JJ, Falk GW, Frey L, Lopez R, Rice TW. An open-label, prospective trial of cryospray ablation for Barrett’s esophagus high-grade dysplasia and early esophageal cancer in high-risk patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:635-644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ghorbani S, Tsai FC, Greenwald BD, Jang S, Dumot JA, McKinley MJ, Shaheen NJ, Habr F, Coyle WJ. Safety and efficacy of endoscopic spray cryotherapy for Barrett’s dysplasia: results of the National Cryospray Registry. Dis Esophagus. 2016;29:241-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gosain S, Mercer K, Twaddell WS, Uradomo L, Greenwald BD. Liquid nitrogen spray cryotherapy in Barrett’s esophagus with high-grade dysplasia: long-term results. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:260-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Greenwald BD, Dumot JA, Abrams JA, Lightdale CJ, David DS, Nishioka NS, Yachimski P, Johnston MH, Shaheen NJ, Zfass AM. Endoscopic spray cryotherapy for esophageal cancer: safety and efficacy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:686-693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Johnston CM, Schoenfeld LP, Mysore JV, Dubois A. Endoscopic spray cryotherapy: a new technique for mucosal ablation in the esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:86-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Khangura SK, Greenwald BD. Endoscopic management of esophageal cancer after definitive chemoradiotherapy. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:1477-1485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Leggett CL, Gorospe EC, Wang KK. Endoscopic therapy for Barrett’s esophagus and early esophageal adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2013;42:175-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ribeiro A, Bejarano P, Livingstone A, Sparling L, Franceschi D, Ardalan B. Depth of injury caused by liquid nitrogen cryospray: study of human patients undergoing planned esophagectomy. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:1296-1301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Shaheen NJ, Greenwald BD, Peery AF, Dumot JA, Nishioka NS, Wolfsen HC, Burdick JS, Abrams JA, Wang KK, Mallat D. Safety and efficacy of endoscopic spray cryotherapy for Barrett’s esophagus with high-grade dysplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:680-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Shaheen NJ, Sharma P, Overholt BF, Wolfsen HC, Sampliner RE, Wang KK, Galanko JA, Bronner MP, Goldblum JR, Bennett AE. Radiofrequency ablation in Barrett’s esophagus with dysplasia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2277-2288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1146] [Cited by in RCA: 974] [Article Influence: 60.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Xue HB, Tan HH, Liu WZ, Chen XY, Feng N, Gao YJ, Song Y, Zhao YJ, Ge ZZ. A pilot study of endoscopic spray cryotherapy by pressurized carbon dioxide gas for Barrett’s esophagus. Endoscopy. 2011;43:379-385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |