Published online Sep 16, 2017. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v9.i9.471

Peer-review started: March 28, 2017

First decision: June 30, 2017

Revised: July 10, 2017

Accepted: August 15, 2017

Article in press: August 16, 2017

Published online: September 16, 2017

Processing time: 168 Days and 8.1 Hours

To compare colonoscopy quality with nitrous oxide gas (Entonox®) against intravenous conscious sedation using midazolam plus opioid.

A retrospective analysis was performed on a prospectively held database of 18608 colonoscopies carried out in Lothian health board hospitals between July 2013 and January 2016. The quality of colonoscopies performed with Entonox was compared to intravenous conscious sedation (abbreviated in this article as IVM). Furthermore, the quality of colonoscopies performed with an unmedicated group was compared to IVM. The study used the following key markers of colonoscopy quality: (1) patient comfort scores; (2) caecal intubation rates (CIRs); and (3) polyp detection rates (PDRs). We used binary logistic regression to model the data.

There was no difference in the rate of moderate-to-extreme discomfort between the Entonox and IVM groups (17.9% vs 18.8%; OR = 1.06, 95%CI: 0.95-1.18, P = 0.27). Patients in the unmedicated group were less likely to experience moderate-to-extreme discomfort than those in the IVM group (11.4% vs 18.8%; OR = 0.71, 95%CI: 0.60-0.83, P < 0.001). There was no difference in caecal intubation between the Entonox and IVM groups (94.4% vs 93.7%; OR = 1.08, 95%CI: 0.92-1.28, P = 0.34). There was no difference in caecal intubation between the unmedicated and IVM groups (94.2% vs 93.7%; OR = 0.98, 95%CI: 0.79-1.22, P = 0.87). Polyp detection in the Entonox group was not different from IVM group (35.0% vs 33.1%; OR = 1.01, 95%CI: 0.93-1.10, P = 0.79). Polyp detection in the unmedicated group was not significantly different from the IVM group (37.4% vs 33.1%; OR = 0.97, 95%CI: 0.87-1.08, P = 0.60).

The use of Entonox was not associated with lower colonoscopy quality when compared to intravenous conscious sedation using midazolam plus opioid.

Core tip: Previous studies have shown that colonoscopies performed with Entonox® gas are not associated with more patient discomfort, or lower caecal intubation rates, than those performed with intravenous conscious sedation. We have completed the largest and most comprehensive real-world retrospective study of Entonox use in colonoscopy. In particular, we compare colonoscopy quality with Entonox against intravenous conscious sedation using midazolam plus opioid. This study shows that Entonox is not associated with lower colonoscopy quality when compared to intravenous conscious sedation. Based on the results of this study, Entonox remains an attractive option for colonoscopy analgesia and sedation.

- Citation: Robertson AR, Kennedy NA, Robertson JA, Church NI, Noble CL. Colonoscopy quality with Entonox®vs intravenous conscious sedation: 18608 colonoscopy retrospective study. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2017; 9(9): 471-479

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v9/i9/471.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v9.i9.471

Nitrous oxide gas (N2O) has well established analgesic and sedative properties[1-4]. It is likely that the analgesic effect of nitrous oxide is opioid receptor-mediated[5,6]. Furthermore, and although less well characterised, animal models suggest that the anxiolytic effect of nitrous oxide is benzodiazepine receptor-mediated[7].

Entonox® (50% nitrous oxide: 50% oxygen) is routinely used as a patient-controlled inhaled analgesic and sedative. In particular, it is used in various emergency, orthopaedic, and obstetric procedures[8,9]. It is not as frequently used in gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy, with intravenous conscious sedation (benzodiazepine use in combination with an opioid) being the standard sedation regime in the United Kingdom[10].

A useful way of examining standards in colonoscopy practice is to use the framework of “colonoscopy quality[11-13]. The aim of current colonoscopy quality guidelines [jointly adopted by the Joint Advisory Group on GI Endoscopy, the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG), and the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland] is to improve patient care[14]. Three important markers of colonoscopy quality are: (1) < 10% of patients should experience moderate or severe discomfort; (2) the caecal intubation rate (CIR) should be ≥ 90%; and (3) the polyp detection rate (PDR) should be ≥ 15%[14].

Welchman et al[15] conducted a systematic review of Entonox use in colonoscopy. Their review, which included a total of 623 patients, was based on data from 9 small randomised controlled trials (RCTs). The authors concluded that “N2O provides comparable analgesia to i.v. sedation”. A Cochrane review of 547 patients (from 7 of the RCTs), where the primary outcome was adequate pain relief during the procedure, similarly, reached the conclusion that Entonox was “as efficient” as intravenous sedation in reducing pain/discomfort during colonoscopy[16].

Neither the Welchman et al[15] and Aboumarzouk et al[16] nor Cochrane reviews found (based on more limited data) any difference in CIRs when Entonox and intravenous sedation groups were compared directly. However, CIRs were found, in a large prospective study by Radaelli et al[17], to be higher in the intravenous benzodiazepine (n = 3701; CIR = 83.1%) vs unsedated (n = 5737; CIR = 76.1%) groups (OR = 1.460, 95%CI: 1.282-1.663). Radaelli et al[17] also demonstrated that PDRs were higher in intravenous benzodiazepine (n = 3701; PDR = 26.9%) vs unsedated (n = 5737; PDR = 26.5%) groups (OR = 1.121, 95%CI: 1.016-1.236). A small study at a UK private hospital found a higher adenoma detection rate (but not PDR) in the Entonox group compared to the intravenous sedation group[18].

Endoscopic procedure data from UK endoscopy units have been used to retrospectively analyse colonoscopy quality associated with different types of analgesia/sedation. Two independently conducted retrospective studies of NHS endoscopy units (one of 2873 patients at Altnagelvin Area Hospital, Northern Ireland[19] and another of 322 patients at Furness General Hospital, England[20]) have found that CIRs, PDRs, and patient comfort scores were similar in patients receiving Entonox vs intravenous sedation.

In this study we assessed the quality of colonoscopies performed with Entonox against intravenous conscious sedation (abbreviated in this article as IVM) using intravenous midazolam plus opioid. We also compared colonoscopy quality with an unmedicated group against IVM. We used the following markers of colonoscopy quality: (1) patient comfort scores; (2) CIRs; and (3) PDRs.

Eighteen thousand six hundred and eight colonoscopies were undertaken between July 2013 and January 2016 at one of four NHS colonoscopy units within Lothian health board: (1) the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh; (2) the Western General Hospital, Edinburgh; (3) St John’s Hospital, Livingston; or (4) Roodlands Hospital, Haddington. Relevant patient and procedural data was recorded by the endoscopist/nurse at the time of colonoscopy using Unisoft’s electronic GI Reporting Tool (Unisoft Medical Systems, Enfield, United Kingdom). The database was retrospectively analysed.

Procedures were performed using Olympus XQ 240 and XQ260 and Fuji EC530WL and EC600WL colonoscopes. Generally during the procedures the endoscopist and two nurses where present, regardless of regime type, and patients routinely had blood pressure, heart rate and oxygen saturation monitoring.

At each of these units, throughout this timeframe, patients were offered the choice of either: (1) Entonox; (2) intravenous conscious sedation (IVM) with midazolam plus or minus opioid; or (3) no sedation or analgesia (i.e., unmedicated), each administered by the performing endoscopist. Patients offered Entonox had the option of fentanyl plus or minus midazolam as an adjunct if required and clinically appropriate. There were 234 individual cases of patients receiving both Entonox and midazolam sedation (1.26% of the total), and all these cases were all excluded from the analysis. This situation could have arisen in the case where the patient was not adequately responding to IVM and Entonox was then introduced as an adjunct or vice versa. Ninety-nine percent of patients receiving IVM had a combination of fentanyl analgesia and midazolam sedation at the start of the procedure.

Local exclusion criteria for the use of Entonox are head injury or altered GCS, maxillo-facial injuries, drug or alcohol intoxication, pneumothorax or chest trauma, decompensated respiratory disease, decompression sickness or recent underwater diving, the first sixteen weeks of pregnancy, middle ear occlusion, high risk infection, e.g., MRSA/VRE or vitamin B12 deficiency (see the regulator-approved summary of product characteristics[21]).

A “polyp” was defined as such by the performing endoscopist when reporting the investigation. For the purpose of this study polyps were either detected or not detected. Caecal intubation was confirmed by identification of caecal landmarks and recording these in the reporting software with supporting photo-documentation where possible. For the purpose of this study caecal intubation was either achieved or was not achieved.

Patient comfort score was endoscopist/nurse reported and recorded as either: “no discomfort”, “mild discomfort”, “moderate discomfort”, “severe discomfort”, or “extreme discomfort”.

In the primary analysis “moderate”, “severe”, and “extreme” discomfort were combined into a single “moderate-to-extreme” discomfort binary variable because this was felt to be the most clinically relevant approach and is consistent with the current United Kingdom colonoscopy quality guidelines[14]. A secondary analysis compared rates of mild discomfort between sedation groups. This analysis only included the subgroup of patients that had either “no” or “mild” discomfort, i.e., patients with either “moderate, “severe”, and “extreme” discomfort were excluded from the analysis. Therefore, in this secondary analysis, the new patient comfort variable was again a binary variable.

The data were exported from the Unisoft GI reporting tool to an Excel 2016 spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, WA, United States). The statistical analysis was subsequently performed by importing the data into the software package R Version 3.2.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The caecal intubation and polyp detection variables were separately analysed using binary logistic regression to assess for an association with different types of colonoscopy analgesia/sedation. The caecal intubation and polyp detection fields were treated as binary dependent variables. Patient age and gender were included as independent variables.

One thousand five hundred and one colonoscopies were excluded for one or more of 5 reasons: (1) the patient was a child under the age of 18 (n = 35); (2) the comfort score was not recorded (n = 154); (3) the patient had undergone a general anaesthetic (n = 26); (4) the patient was administered both Entonox and midazolam (n = 234); and (5) the patient had opioid alone (n = 1091). This left a total of 17107 patients to be included in the final analysis (Table 1).

| Variable | Type of analgesia/sedation | ||

| Midazolam ± opioid | Entonox ± opioid | Unmedicated | |

| Gender | |||

| Female (% of females) | 6753 (76.0%) | 1609 (18.1%) | 520 (5.9%) |

| Male (% of males) | 4613 (56.1%) | 2239 (27.2%) | 1373 (16.7%) |

| Median age/yr (IQR) | 61.1 (50.7-70.1) | 60.4 (50.8-69.1) | 63.8 (54.3-71.4) |

| Median midazolam dose/mg (IQR) | 2.5 (2.0-3.0) | ||

| Opioid, mcg | |||

| Number (%) given fentanyl | 10255 (90.2%) | 258 (6.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Number (%) given pethidine | 1060 (9.3%) | 27 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Total number (%) given an opioid | 11299 (99.4%) | 284 (7.4%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Median fentanyl equivalent dose (IQR) | 75.0 (50.0-100.0) | 75.0 (50.0-100.0) | |

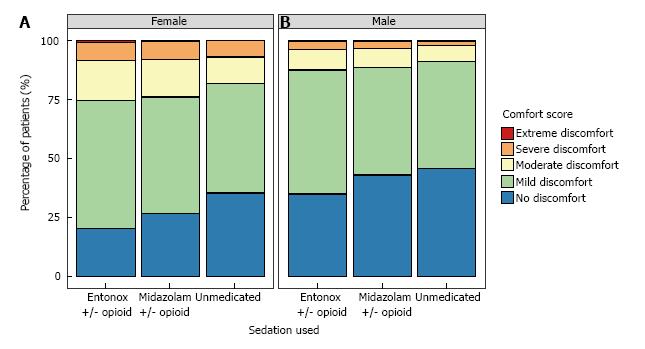

A graphical representation of comfort scores by analgesia/sedation type and gender is shown in Figure 1. There was no difference in the rate of moderate-to-extreme discomfort in the Entonox group compared to the IVM group (17.9% vs 18.8%; OR = 1.06, 95%CI: 0.95-1.18, P = 0.27) (Table 2). Patients in the unmedicated group were less likely to experience moderate-to-extreme discomfort than those in the IVM group (11.4% vs 18.8%; OR = 0.71, 95%CI: 0.60-0.83, P < 0.001).

| Variable1 | No. with moderate-to-extreme discomfort (%)2 | Odds ratio (95%CI)1 | P value1 |

| Sedation type | |||

| Midazolam ± opioid | 2137 (18.8) | Reference | |

| Entonox ± opioid | 689 (17.9) | 1.06 (0.95-1.18) | 0.27 |

| Unmedicated | 215 (11.4) | 0.71 (0.60-0.83) | < 0.001 |

| Age | 1.00 (1.00-1.01) | 0.08 | |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 2114 (23.9) | Reference | |

| Male | 927 (11.3) | 0.40 (0.36-0.43) | < 0.001 |

There was no statistical association of age with moderate-to-extreme discomfort (OR = 1.00, 95%CI: 1.00-1.01, P = 0.08). Males were less likely to experience moderate-to-extreme discomfort than females (11.3% vs 23.9%; OR = 0.40, 95%CI: 0.36-0.43, P < 0.001).

Amongst only those patients experiencing mild or no discomfort, Entonox was associated with greater likelihood of mild discomfort compared to IVM (64.7% vs 58.9%; OR = 1.46, 95%CI: 1.33-1.61, P < 0.001).

In addition to the exclusions listed at the beginning of this section, 74 cases where the extent of intubation was listed as “anastomosis” were excluded from the caecal intubation calculation. A further 3 cases where the extent of intubation was not recorded were also excluded.

There was no difference in caecal intubation between the Entonox and IVM groups (94.4% vs 93.7%; OR = 1.08, 95%CI: 0.92-1.28, P = 0.34) (Table 3). Furthermore, there was no difference in caecal intubation between the unmedicated and IVM groups (94.2% vs 93.7%; OR = 0.98, 95%CI: 0.79-1.22, P = 0.87).

| Variable1 | Caecal intubation rate, n (%)2 | Odds ratio (95%CI)1 | P value1 |

| Sedation type | |||

| Midazolam ± opioid | 10562 (93.7) | Reference | |

| Entonox ± opioid | 3612 (94.4) | 1.08 (0.92-1.28) | 0.34 |

| Unmedicated | 1763 (94.2) | 0.98 (0.79-1.22) | 0.87 |

| Age | 0.98 (0.97-0.98) | < 0.001 | |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 8159 (92.7) | Reference | |

| Male | 7778 (95.3) | 1.61 (1.41-1.85) | < 0.001 |

There was a negative association of age with caecal intubation (OR = 0.98, 95%CI: 0.97-0.98, P < 0.001). Males had higher caecal intubation compared to females (95.3% vs 92.7%; OR = 1.61, 95%CI: 1.41-1.85, P < 0.001).

Polyp detection in the Entonox group was not significantly different from the IVM group (35.0% vs 33.1%; OR = 1.01, 95%CI: 0.93-1.10, P = 0.79) (Table 4). Furthermore, polyp detection in the unmedicated group was not significantly different from the IVM group (37.4% vs 33.1%; OR = 0.97, 95%CI: 0.87-1.08, P = 0.60).

There was a positive association of age with polyp detection (OR = 1.03, 95%CI: 1.03-1.03, P < 0.001). Males had higher polyp detection compared to females (40.8% vs 27.7%; OR = 1.83, 95%CI: 1.71-1.96, P < 0.001).

Previous systematic reviews of the clinical trial data, although limited by the small sample sizes of the constituent trials, show nitrous oxide to be as effective as IVM in controlling patient discomfort during colonoscopy. Furthermore, they show that CIRs are comparable between the two groups[15,16]. The two independently conducted retrospective studies of real-world colonoscopy data have also suggested equivalence between nitrous oxide and IVM. However, in addition to their relatively small sample size, these latter studies were notably limited by the way in which they analysed the data using descriptive and basic inferential statistics[19,20]. There has therefore been a need for a larger and more comprehensive retrospective study.

In our study we used binary logistic regression to model the data. We found no difference in moderate-to-extreme discomfort experienced, caecal intubation, and polyp detection between the intravenous medication and Entonox groups.

Our study therefore supports and strengthens the data from existing studies in suggesting that using Entonox is not associated with lower colonoscopy quality than IVM.

The key implication of this finding is that patients can continue to be offered the same level of choice with respect to their colonoscopy analgesia/sedation. There are many factors associated with Entonox use that may be attractive to patients relative to IVM. For example, some patients are likely to be attracted by the rapid post-procedure recovery associated with Entonox use[15,16]. In particular, after using Entonox patients have the potential to be discharged after just 30 min[22], are safe to drive[23], and do not require overnight home supervision by a responsible person. This could manifest itself in improved patient satisfaction levels with their post-procedural care. Furthermore, although outside the remit of this study, it could contribute to efficiency and cost savings in the endoscopy department by optimising patient flow.

As measured by CIR and PDR the overall quality of colonoscopy performed in the included centres was good. All groups met the ≥ 90% (CIR) and ≥ 15% (PDR) BSG/Joint Advisory Group on GI Endoscopy/Association of Coloproctology standards[14]. Furthermore we were gratified, because of its implication of good colonoscopy technique, to see that the unmedicated group experienced a lower level of discomfort compared to the IVM group. We are not aware of any previous studies demonstrating an association of no sedation with lower levels of patient discomfort. Ristikankare et al[24] found no significant difference in patient experience between an intravenous midazolam sedation group and a no intravenous cannula control group. Furthermore, studies have demonstrated the feasibility of unsedated colonoscopy[25,26]. The NordICC study is a large population-based RCT into the effectiveness of colonoscopy screening for colorectal cancer. The NordICC study group has published an interim data analysis showing that overall “pain during colonoscopy was not significantly associated with the use of sedation (adjusted odds ratio, 0.91; 95%CI: 0.61-1.35)”[27].

Within this analysis the CIR and PDR of the unmedicated group where not significantly different compared with the IVM patients.

Polyp detection rate was used rather than adenoma detection as analysis was based on reports written during and immediately following the procedure, and as such prior to histological differentiation of the polyp.

The way that Entonox is used by GI endoscopists in the UK varies. In particular, some endoscopists use Entonox as a primary agent, whereas others use it as an adjunct to another standard analgesia/sedation regime. Within Lothian health board Entonox is principally used as a primary agent. In only 234 cases, 1.26% of the total number, were patients administered both Entonox and intravenous midazolam. Consequently, variability in Entonox use with respect to its primary or adjunctive status was not something that could be addressed by this study.

The introduction of comfort scores in the assessment of colonoscopy quality was initially recommended by the BSG Endoscopy Committee in order to monitor whether, in striving to achieve total colonoscopy to the caecum, endoscopists were causing unacceptable pain and distress to patients[13,28]. However, it has been demonstrated that the best colonoscopists (typically those performing the most procedures per annum) have “a higher CIR, use less sedation, cause less discomfort and find more polyps”[28]. This highlights the importance of the technical skill of the endoscopist in relation to patient comfort during colonoscopy. Indeed, the initial data from the NordICC study show that individual endoscopist performance is associated with significant variability in CIRs, adenoma detection rates, and the percentage of participants with moderate or severe pain[27].

Interestingly, among the subgroup of patients experiencing “none” or “mild” discomfort, Entonox was associated with more patients having “mild” discomfort when compared to IVM. This was a secondary analysis, as it was felt that (in line with the UK guidelines and the ongoing NordICC study) patient discomfort is most important when it is moderate or worse[14,27]. Furthermore, there have been differences reported in the way that nurses, endoscopists, and patients report comfort. In particular, Rafferty et al[29] found that nurses tend to give higher comfort scores, in other words report more discomfort, than the endoscopist and the patient. This suggests that the distinction between “none” and “mild” discomfort is potentially not meaningful. Furthermore, the use of the Entonox apparatus during colonoscopy is likely to be associated with a learning curve, with colonoscopy technique modification required to maximise its effect. As such there is likely to be inter-operator variability in outcomes with Entonox. Within this study there was no data collected on the individual endoscopists experience in relation to patient outcomes but further discussion and study into the importance of the endoscopist with respect to Entonox would be highly beneficial.

There was a marked gender effect in our patient population. Females experienced significantly worse patient comfort scores, CIRs, and PDRs. Indeed, these gender differences in comfort scores[27,30-32], caecal intubation rates or times[33,34], and PDRs/adenoma detection rates[35,36] are well established in the literature. The difference with respect to comfort scores can potentially be accounted for by two physical factors. Firstly, females have a pelvic anatomy, and a longer colon that are more predisposed to “looping” than in males[37,38]. Secondly, gynaecological surgery can result in anatomical distortion and pelvic or abdominal adhesions that make colonoscopy more difficult, and therefore more uncomfortable for the patient. This is supported by the evidence that previous hysterectomy is associated with greater discomfort during colonoscopy[31,39,40]. It has been postulated that responses to pain and discomfort may be related to psychosocial factors[41]. However, we are not aware of any study that has sufficiently differentiated these factors from past surgical history and other considerations. Within our analysis procedures with the limit listed as “anastomosis” have been removed. As further surgeries have been incompletely documented they have not been corrected for. Overall, the uncertainty of the relative importance of these factors highlights the need for future clinical research in colonoscopy analgesia and sedation to consider the possibility of important gender differences generally, as well as more specifically in relation to response to sedation.

There was the potential in this study for patient and endoscopist selection bias. This might explain the observation that unmedicated patients experienced lower levels of discomfort when compared to the IVM group. Patients who had previous high tolerance of colonoscopy for example would be likely to select the unmedicated option. Endoscopist and nurse reporting of comfort scores may also have significant inter-observer variability. Furthermore, patient comfort scores were entirely endoscopist or nurse reported. There was no data recorded on analgesics being taken regularly prior to the procedure or whether the recorded procedure was their first.

Although data was collected on the indications for colonoscopy these were similar between the groups and as such not included in the final analysis.

Procedures were carried out by a combination of gastroenterologists, surgeons and nurse endoscopists with varying experience. This information, and the personal experience of the endoscopist was not included within this study.

Bowel preparation, its quality, colonoscopy technique and complication rates were not included within the data analysed. Within the endoscopy departments a Moviprep based schedule was most commonly used. The predominant technique employed was air insufflations although carbon dioxide insufflation was also common and exceptions to this are likely to be equally distributed among the groups.

This is a large retrospective study whose merits lie not in the systematic elimination of bias but rather in observing the real-world quality markers associated with the different analgesia and sedation regimes. This type of study is therefore important for its ability to encourage and facilitate quality and service improvement.

In conclusion, this study shows that Entonox is not associated with lower colonoscopy quality when compared to intravenous conscious sedation. Entonox therefore remains an attractive option for colonoscopy analgesia and sedation. In most cases, decisions regarding analgesia and sedation are the result of an informed discussion between patient and endoscopist in which several factors, such as patient comorbidities and individual patient preferences, are taken into account.

Previous small randomised controlled trials have shown that colonoscopies performed with Entonox® gas are not associated with more patient discomfort, or lower caecal intubation rates (CIRs), than those performed with intravenous conscious sedation using intravenous conscious sedation (IVM). Furthermore, the two published retrospective studies of “real-world” colonoscopy data have also suggested an equivalence between nitrous oxide and IVM. However, in addition to their relatively small sample size these studies have been limited by their statistical methodology.

The authors have now completed the largest and most comprehensive real-world retrospective study of Entonox use in colonoscopy. In particular, the authors have compared colonoscopy quality with Entonox against intravenous conscious sedation using midazolam plus opioid. The study used the following key markers of colonoscopy quality: (1) patient comfort scores; (2) caecal intubation rates (CIRs); and (3) polyp detection rates (PDRs). The authors used binary logistic regression to model the data.

This study shows that Entonox is not associated with lower colonoscopy quality when compared to intravenous conscious sedation.

Based on the results of this study, Entonox remains an attractive option for colonoscopy analgesia and sedation.

Entonox is the proprietary name of the commercially available compressed gaseous mixture of 50% nitrous oxide: 50% oxygen.

This is a large and interesting study which is well written. The authors demonstrated the equal effectiveness between N2O and intravenous midazolam for patient’s anesthesia in performing the colonoscopy.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Ahluwalia NK, Chiba H, Lee CL, Seow-Choen F S- Editor: Kong JX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Sanders RD, Weimann J, Maze M. Biologic effects of nitrous oxide: a mechanistic and toxicologic review. Anesthesiology. 2008;109:707-722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 229] [Cited by in RCA: 221] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Becker DE, Rosenberg M. Nitrous oxide and the inhalation anesthetics. Anesth Prog. 2008;55:124-130; quiz 131-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Duarte R, McNeill A, Drummond G, Tiplady B. Comparison of the sedative, cognitive, and analgesic effects of nitrous oxide, sevoflurane, and ethanol. Br J Anaesth. 2008;100:203-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | European Society of Anaesthesiology task force on use of nitrous oxide in clinical anaesthetic practice. The current place of nitrous oxide in clinical practice: An expert opinion-based task force consensus statement of the European Society of Anaesthesiology. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2015;32:517-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fukagawa H, Koyama T, Fukuda K. κ-Opioid receptor mediates the antinociceptive effect of nitrous oxide in mice. Br J Anaesth. 2014;113:1032-1038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Fujinaga M, Maze M. Neurobiology of nitrous oxide-induced antinociceptive effects. Mol Neurobiol. 2002;25:167-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Emmanouil DE, Quock RM. Advances in understanding the actions of nitrous oxide. Anesth Prog. 2007;54:9-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | O’Sullivan I, Benger J. Nitrous oxide in emergency medicine. Emerg Med J. 2003;20:214-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Collins MR, Starr SA, Bishop JT, Baysinger CL. Nitrous oxide for labor analgesia: expanding analgesic options for women in the United States. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2012;5:e126-e131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bell GD, McCloy RF, Charlton JE, Campbell D, Dent NA, Gear MW, Logan RF, Swan CH. Recommendations for standards of sedation and patient monitoring during gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gut. 1991;32:823-827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rex DK, Schoenfeld PS, Cohen J, Pike IM, Adler DG, Fennerty MB, Lieb JG 2nd, Park WG, Rizk MK, Sawhney MS, Shaheen NJ, Wani S, Weinberg DS. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:31-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 649] [Cited by in RCA: 836] [Article Influence: 83.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rizk MK, Sawhney MS, Cohen J, Pike IM, Adler DG, Dominitz JA, Lieb JG 2nd, Lieberman DA, Park WG, Shaheen NJ, Wani S. Quality indicators common to all GI endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:3-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Valori R, Barton R. BSG quality and safety indicators for endoscopy. JAG: Joint Advisory Group on GI Endoscopy. 2007;1-13. |

| 14. | Rees CJ, Thomas-Gibson S, Rutter MD, Baragwanth P, Pullan R, Feeney M, Haslam N, on behalf of The British Society of Gastroenterology TJAGoGE, and The Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. UK Key Performance Indicators & Quality Assurance Standards for Colonoscopy, 2015. Available from: http://www.bsg.org.uk/images/stories/docs/clinical/guidance/uk_kpi_qa_standards_for_colonoscopy.pdf. |

| 15. | Welchman S, Cochrane S, Minto G, Lewis S. Systematic review: the use of nitrous oxide gas for lower gastrointestinal endoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:324-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Aboumarzouk OM, Agarwal T, Syed Nong Chek SA, Milewski PJ, Nelson RL. Nitrous oxide for colonoscopy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;CD008506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Radaelli F, Meucci G, Sgroi G, Minoli G; Italian Association of Hospital Gastroenterologists (AIGO). Technical performance of colonoscopy: the key role of sedation/analgesia and other quality indicators. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1122-1130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gupta S, Balicano M, Cooper S, Mead C, Whitton A. PTH-023 Comparison between inhaled entonox and intravenous sedation for colonoscopy at a private hospital. Gut. 2015;64 Suppl 1:A415-A416. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | Tharian B, Ridley T, Dickey W, Murdock A. Sa1125 A Retrospective Study of IV Sedation Versus Nitrous Oxide (Entonox) for Patients Undergoing Colonoscopy. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:S-222-S-223. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Abdel-Halim M, Langley S, Kaushal M. Colonoscopy under entonox is feasible and is associated with potential cost savings: A review of a dgh experience. Int J Surg. 2013;11:630. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | BOC Ltd. Summary of Product Characteristics. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency - GOV.UK: Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. |

| 22. | Trojan J, Saunders BP, Woloshynowych M, Debinsky HS, Williams CB. Immediate recovery of psychomotor function after patient-administered nitrous oxide/oxygen inhalation for colonoscopy. Endoscopy. 1997;29:17-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Martin JP, Sexton BF, Saunders BP, Atkin WS. Inhaled patient-administered nitrous oxide/oxygen mixture does not impair driving ability when used as analgesia during screening flexible sigmoidoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:701-703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ristikankare M, Hartikainen J, Heikkinen M, Janatuinen E, Julkunen R. Is routinely given conscious sedation of benefit during colonoscopy? Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:566-572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Aljebreen AM, Almadi MA, Leung FW. Sedated vs unsedated colonoscopy: a prospective study. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:5113-5118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Petrini JL, Egan JV, Hahn WV. Unsedated colonoscopy: patient characteristics and satisfaction in a community-based endoscopy unit. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:567-572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Bretthauer M, Kaminski MF, Løberg M, Zauber AG, Regula J, Kuipers EJ, Hernán MA, McFadden E, Sunde A, Kalager M, Dekker E, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Garborg K, Rupinski M, Spaander MC, Bugajski M, Høie O, Stefansson T, Hoff G, Adami HO; Nordic-European Initiative on Colorectal Cancer (NordICC) Study Group. Population-Based Colonoscopy Screening for Colorectal Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:894-902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 27.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ekkelenkamp VE, Dowler K, Valori RM, Dunckley P. Patient comfort and quality in colonoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2355-2361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Rafferty H, Hutchinson J, Ansari S, Smith L-A. PWE-040 Comfort Scoring For Endoscopic Procedures: Who Is Right – The Endoscopist, The Nurse Or The Patient? Gut. 2014;63 Suppl 1:A139-A140. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 30. | Lai W, Fung M, Vatish J, Pullan R, Feeney M. How Gender And Age Affect Tolerance Of Colonoscopy. Gut. 2013;62 Suppl 2:A45-A46. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 31. | Hull T, Church JM. Colonoscopy--how difficult, how painful? Surg Endosc. 1994;8:784-787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kim WH, Cho YJ, Park JY, Min PK, Kang JK, Park IS. Factors affecting insertion time and patient discomfort during colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:600-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Shah HA, Paszat LF, Saskin R, Stukel TA, Rabeneck L. Factors associated with incomplete colonoscopy: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2297-2303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 267] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Anderson JC, Messina CR, Cohn W, Gottfried E, Ingber S, Bernstein G, Coman E, Polito J. Factors predictive of difficult colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:558-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Sanaka MR, Gohel T, Podugu A, Kiran RP, Thota PN, Lopez R, Church JM, Burke CA. Adenoma and sessile serrated polyp detection rates: variation by patient sex and colonic segment but not specialty of the endoscopist. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57:1113-1119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Rex DK, Bond JH, Winawer S, Levin TR, Burt RW, Johnson DA, Kirk LM, Litlin S, Lieberman DA, Waye JD. S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Quality in the technical performance of colonoscopy and the continuous quality improvement process for colonoscopy: recommendations of the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1296-1308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 691] [Cited by in RCA: 723] [Article Influence: 31.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Streett SE. Endoscopic colorectal cancer screening in women: can we do better? Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:1047-1049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Rowland RS, Bell GD, Dogramadzi S, Allen C. Colonoscopy aided by magnetic 3D imaging: is the technique sufficiently sensitive to detect differences between men and women? Med Biol Eng Comput. 1999;37:673-679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Dyson JK, Mason JM, Rutter MD. Prior hysterectomy and discomfort during colonoscopy: a retrospective cohort analysis. Endoscopy. 2014;46:493-498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Rutter MD. Colonoscopy in Patients With a Prior Hysterectomy. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2015;11:64-66. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Fillingim RB, King CD, Ribeiro-Dasilva MC, Rahim-Williams B, Riley JL 3rd. Sex, gender, and pain: a review of recent clinical and experimental findings. J Pain. 2009;10:447-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1928] [Cited by in RCA: 1866] [Article Influence: 116.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |