Published online Jul 16, 2017. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v9.i7.334

Peer-review started: November 2, 2016

First decision: December 1, 2016

Revised: January 20, 2017

Accepted: March 23, 2017

Article in press: March 24, 2017

Published online: July 16, 2017

Processing time: 249 Days and 9.9 Hours

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) using the clutch cutter (CC) (ESD-CC) for gastric adenoma (GA).

From June 2007 to August 2015, 122 consecutive patients with histological diagnoses of GA from specimens resected by ESD-CC were enrolled in this prospective study. The CC was used for all ESD steps (marking, mucosal incision, submucosal dissection, and hemostatic treatment), and its therapeutic efficacy and safety were assessed.

Both the en-bloc resection rate and the R0 resection rate were 100% (122/122). The mean surgical time was 77.4 min, but the time varied significantly according to tumor size and location. No patients suffered perforation. Post-ESD-CC bleeding occurred in six cases (4.9%) that were successfully resolved by endoscopic hemostatic treatment.

ESD-CC is a technically efficient, safe, and easy method for resecting GA.

Core tip: The clutch cutter (CC) was developed to reduce risk of complications related to endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) using conventional knives. The CC can grasp, pull, coagulate and/or incise targeted tissue using electrosurgical current, as with a bite biopsy. The CC can be used in all ESD steps (marking, mucosal incision, submucosal dissection, and hemostatic treatment). ESD using the CC (ESD-CC) for gastric adenoma (GA) gave a 100% R0 resection rate in this study, with no perforation. ESD-CC is a technically efficient, safe, and easy method for resecting GA.

- Citation: Akahoshi K, Kubokawa M, Gibo J, Osada S, Tokumaru K, Yamaguchi E, Ikeda H, Sato T, Miyamoto K, Kimura Y, Shiratsuchi Y, Akahoshi K, Oya M, Koga H, Ihara E, Nakamura K. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastric adenomas using the clutch cutter. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2017; 9(7): 334-340

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v9/i7/334.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v9.i7.334

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) has considerable advantages regarding rates for local recurrence, and en-bloc and R0 resections, compared with conventional endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR)[1,2]. Worldwide, ESD gradually increases in its indication share instead of EMR. However, the major disadvantages of ESD with conventional knives is its technical difficulty; Therefore, it has a high complication incidence and protracted procedural time, requiring advanced endoscopic skills and many devices[3-5]. Conventional devices (such as IT and needle knives) are gently pushed to the targeted tissue; then, these tissues are cut using electrosurgical current. Because these cutting mechanisms cannot grasp or pull at the targeted tissue, accurate targeting, compressive hemostasis and the ability to draw the targeted tissue away from the muscle layer are lacking, causing the risk of serious adverse events including gastric perforation and hemorrhage[6,7]. In order to resolve the hazards of ESD using conventional knives, the Clutch Cutter (CC) was developed and can precisely grasp, pull, coagulate, and/or resect the targeted tissue using high frequency current[5-9]. In our previous prospective study of early gastric cancers (EGCs), we were able to remove cancers safely and easily without unexpected electrical tissue damage by using ESD with the CC (ESD-CC)[5]. However, until now clinical performance in many patients with GA treated by this new method of ESD-CC has not been sufficiently investigated. In this study, we evaluated the clinical performance of ESD-CC for GA in larger number of patients.

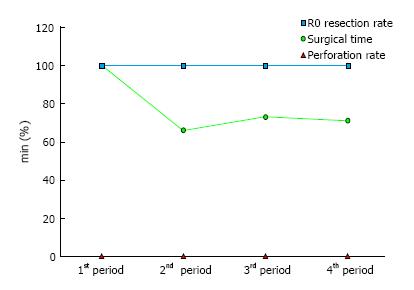

We enrolled 122 consecutive patients (78 men, 44 women; mean age: 71.8 years, range: 52-91 years) who were histologically diagnosed with GA using specimens resected by ESD-CC at Aso Iizuka Hospital from June 2007 to December 2015 (Table 1) in this study. R0 resection (en-bloc resection with negative horizontal and vertical margins) is considered to be curative. To evaluate the learning curve for ESD-CC, 122 cases were grouped chronologically into four periods: (1) cases 1-30; (2) cases 31-60; (3) cases 61-90; and (4) cases 91-122. This study was carried out at Aso Iizuka Hospital and was approved by its ethics committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

| Sex, male/female | 78/44 |

| mean ± SD (range) age years | 71.9 ± 8.4 (52-91) |

| Locatio | |

| Lower | 44 (36) |

| Middle | 54 (44) |

| Upper | 24 (20) |

| Macroscopic type | |

| I (protruded) | 10 (8) |

| IIa (flat elevated) | 65 (53) |

| IIa + IIc | 16 (13) |

| Ic + IIa | 5 (4) |

| IIa + I | 2 (2) |

| IIc (shallow depressed) | 24 (20) |

The clutch cutter (CC) (DP2618DT, FUJIFILM Corporation, Tokyo, Japan; Video 1) has serrated jaws that allow the endoscopist to grasp the targeted tissue securely. The width and length of the jaws is 0.4-mm and 5-mm respectively[5-9]. The jaws can be rotated 360 degrees and the outer edges are insulated to minimize the electrical risk. The diameter of the insertion portion is 2.7 mm. The CC can manage all steps of ESD. The high-frequency electrosurgical unit is the VIO 300D (Erbe, Tübingen, Germany). The forced coagulation mode (30 W, effect 3) was used for marking. The Endocut-Q mode (effect 2, duration 3, interval 1) was used for mucosal incision and submucosal dissection, whereas the soft coagulation mode (effect 5, 100 W) was used for hemostasis and preventive coagulation (pre-cut and post-ESD).

The ESD-CC procedures were performed by two endoscopists; one maneuvered the video-endoscope, and the other one operated the CC. The ESD-CC procedure used a one-channel endoscope with water jet function (EG-450RD5, EG-530RD5, Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan) or a two-channel multi-bending endoscope with water jet function (GIF-2T240M; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). A transparent attachment (F-01, Top Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was fitted onto the tip of the endoscope to obtain an adequate endoscopic view and to create tension on the targeted submucosal tissue during ESD-CC.

Using the CC in closed mode, dots placed approximately 5 mm outside the lesion margin were made to mark the circumference of the target lesion. Next, 1-2 mL of hyaluronic acid solution (MucoUp: Johnson and Johnson Co., Tokyo, Japan) mixed with small volumes of epinephrine and indigo carmine dye were injected into the submucosal layer; this injection was repeated a few times to obtain sufficient elevation of the mucosa (Videos 2 and 3).

A mucosal incision and subsequent submucosal excision using the CC were repeated to remove the lesion en-bloc. The bleeding artery or vein was grasped, pulled or lifted, and coagulated with the CC to stop the bleeding. Finally, the en-bloc resection of the lesion was completed. All incisions and excisions consisted of four basic procedures: (1) grasping; (2) pulling or lifting up; (3) initiating precut-coagulation with soft coagulation (if a blood vessel is observed); and (4) cutting with the Endo-cut Q.

All resected specimens were sectioned into 2-mm wide slices. Histological diagnosis, tumor diameter, infiltration depth, presence of ulcer, and tumor involvement of horizontal and vertical margins were evaluated.

Surgical time was calculated as the time from the beginning of the submucosal injection to the end of the submucosal dissection. En-bloc resection was defined as the lesion being removed in one piece with macroscopically intact resection margins.

Involvement of the tumor to the resected margins was determined as R0 (en-bloc resection with histologically lateral and basal tumor-free resection margins), R1 (incomplete resection with histologically tumor-positive lateral or basal margins), or Rx (resection with unevaluable histological tumor margins resulting from burning effects or multiple-piece resection). All patients stayed in the hospital for 7 d following the procedure, after which follow-up endoscopic examinations were conducted at 2 d, then at 2 (or 3) mo, and annually thereafter. All patients took proton pump inhibitors for a minimum of 8 wk.

All data analysis was conducted with a statistical software package (SAS version 9.2 and JMP version 8.0.1, SAS Institute Inc, NC, United States). The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to evaluate differences with respect to tumor size and location, and ESD-CC surgical time. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Table 1 shows the patients’ clinical findings. The ratio between males and females was 1.8: 1 (78/44), and the average age was 71.9 years (52-91 years of age). Table 2 shows technical outcomes. The step of grasping and lifting or pulling before cutting the target tissue facilitated the confirmation of the distance between the grasped tissue and the proper muscle layer and enabled the use of sufficient pre-cut coagulation. All tumors could be removed easily and safely without unexpected incision. The mean diameters of GAs were 15.3 ± 8.8 mm. The mean size of resected specimens were 41.4 ± 14.3 mm. Rates for both en-bloc resections and R0 resections were 100%. Mean surgical time was 77.4 ± 52.8 min.

| mean ± SD size of the lesion, mm (range) | 15.3 ± 8.8 (2-43) |

| mean ± SD size of resected specimen, mm (range) | 41.4 ± 14.3 (8-90) |

| En-bloc resection rate (%) | 122/122 (100) |

| R0 resection rate (%) | 122/122 (100) |

| mean ± SD surgical time, min (range) | 77.4 ± 52.8 (13-325) |

| Complication rate | 6/122 (4.9) |

| Intra-ESD perforation rate | 0/122 (0) |

| Intra-ESD uncontrollable bleeding rate | 0/122 (0) |

| Post-ESD bleeding rate | 6/122 (4.9) |

| Post-ESD perforation rate | 0/122 (0) |

During ESD-CC, we encountered no uncontrollable bleeding. Post-ESD bleeding was observed in 4.9% (6/122) of cases. All postoperative bleeding was successfully treated by endoscopic hemostasis using mechanical clip or electrical hemostatic forceps. No patients suffered perforation. Tumor size and location significantly affected the mean surgical time (Table 3).

| Tumor size | |

| 0-20 mm | 65.2 ± 41.6 (13-260) |

| 21-mm | 116.3 ± 65.6 (29-325) |

| P value | P < 0.001 |

| Location | |

| Lower | 57.5 ± 32.4 (13-192) |

| Middle | 85.7 ± 58.5 (21-325) |

| Upper | 94.8 ± 60.1 (32-264) |

| P value | P < 0.005 |

Learning curves showed changes in proficiency over time (Figure 1). Proficiency was expressed as surgical time only; because we had a 100% R0 resection rate and a 0% perforation rate, these parameters were not used to assess proficiency. The surgical time in the introduction stage of ESD-CC was significantly longer than in later stages (P < 0.01).

Gastric adenoma is usually a benign localized protruding neoplastic lesion, and is a histopathologically, proliferation of mildly atypical epithelium and tubular and/or papillary structures[10,11]. Since the prevalence of cancerous change of gastric adenoma is relatively low, it is generally considered that follow-up observation is sufficient if the biopsy result during periodic endoscopic examination is Group III and there is no increase in size or change in morphology of the lesion[12]. However, non-invasive carcinomas sometimes coexist within GAs and can progress to invasive carcinomas[12,13]. Generally, if a GA is diagnosed through an endoscopic forceps biopsy, the possibility that the lesion has not been diagnosed correctly or that the presence of cancer lesions is overlooked should be carefully considered[13]. Therefore, a total biopsy, such as endoscopic resection, is often used to obtain a conclusive diagnosis. Although most GAs are removed by conventional EMR, ESD has a high R0 resection rate regardless of the size of the tumor, it allows for more accurate and detailed histopathological examination compared with the EMR, and the recurrence rate can also be reduced[2-5]. However, ESD is a more difficult and meticulous procedure than EMR, and occasionally causes serious complications. GA is basically a benign disease, and the aim of ESD for this disease is total biopsy. Therefore, safety is vital for performing ESD, and a new and safer device is wanted in this situation.

To resolve the adverse events associated with conventional ESD using a knife devices, Akahoshi and FujiFilm developed the Clutch Cutter (CC) which can accurately grasp, pull, coagulate, and/or cut targeted tissue using high frequency current[5,8,9]. The CC has four main mechanical functions: (1) fixation (precise targeting); (2) pulling or lifting up (away from the proper muscle layer); (3) compression (high hemostatic capability); and (4) outside insulation (minimization of outside electric damage)[5-9]. In this investigation and in our previous studies[5-9,14-17], no unintentional incisions were made, and we were able to stop intra-ESD bleeding promptly and without difficulty using the CC without changing devices (Video 2). ESD-CC is performed only by grasping, pulling (or lifting up), and cutting or coagulating procedures; most endoscopists may accept it without difficulty, because ESD-CC is similar to a forceps biopsy (Videos 2 and 3). Moreover, the CC is available for all ESD sub-procedures. These benefits of ESD-CC seem to be effective for reducing the difficulty level of ESD procedures, the frequency of adverse events, and cost [5-7].

Reported performance ranges for the use of knife devices in EGCs were en-bloc resection rate: 94.9%-97.7%; R0 resection rate: 82%-95.5%; and surgical time: 47.8-108.1 min[2,4,5,18-20]. In our previous study, these rates were en-bloc resection rate: 99.7%; R0 resection rate: 95.3%; and mean procedure time using the CC for EGC: 97.2 min[5], and in this study, these variables were 100%, 100%, and 77.4 min, respectively, using the CC for GA. Thus, rates for en-bloc and R0 resection and surgical time of ESD-CC for GAs appears to be slightly better than those of ESD for EGC using a conventional knife. We hypothesize that these better results are because of the CC’s fixation mechanism (improving target accuracy), and the fact that GA does not cause ulcerative changes.

Perforation by ESD procedures is of two types, depending on time of onset. The first type is intra-ESD perforation, which is mainly the result of an electrical incision of the proper muscle layer by knife devices. The second fashion is post-ESD perforation that ordinarily shows 1-2 d after the ESD procedure because of deep coagulation. Intra-ESD perforation reportedly occurs in 1.2%-8.2% of gastric ESDs[3,5,21,22]. Avoiding electric damage to the proper muscle layer is important to avoid unintended incisions. The CC’s mechanisms, such as the grasping function (allowing accurate targeting), pulling function and external insulation are very effective in preventing intra-ESD perforation, and we had none in this ESD-CC study for GAs (0%). Although post-ESD perforation is a rare complication (0.45%), it can lead to serious conditions that often require emergency surgery[23,24]. Deep thermal damage to the proper muscle layer is considered to be the main cause of perforation after ESD. A gentle push of the knife to the visible vessel using adequate power and duration of electrosurgical coagulation for hemostatic treatment is vital to avoid delayed perforation, a maneuver that requires considerable skill. In addition, there are currently no hemostatic devices with external insulation. These mechanical problems of currently available ESD devices can be associated with Post-ESD perforation. The mechanical advantages of the CC including the pull effect and external insulation are effective to prevent deep thermal tissue damage; we had no post-ESD perforations in this ESD-CC study for GAs.

Bleeding from ESD procedures is also of two types, depending on the time of onset. The first type is intra-ESD bleeding that usually occurs during mucosal incision and submucosal excision. The second type is post-ESD bleeding that occurs after the ESD procedure. Although intra-ESD bleeding occurs frequently, measuring its severity is difficult. Reportedly, significant intra-ESD bleeding occurs in 7% of procedures[25]. Its prevention and quick hemostasis are crucial because bleeding can lead to a poor endoscopic view, resulting in increased surgical time and the likelihood of perforation. Prophylactic electrosurgical coagulation of visible blood vessels and quickly stopping any bleeding are critical to safe ESDs. The CC can fix (accurately target), pull or lift-up (decreased deep thermal tissue damage), and compress (high hemostatic capability) the target tissue[5-7]. Therefore, the CC can perform effective precut coagulation and stop intra-ESD hemorrhage quickly without changing the device. We encountered no uncontrollable intra-ESD bleeding in this study. Reportedly, post-ESD gastric bleeding occurs in 5.3%-15.6% of procedures[3,21,25-28], usually within a week after ESD. Therefore, patients are hospitalized for seven days after ESDs in our institute. The CC can perform precut coagulation or coagulation for exposed blood vessels of a bottom of ESD ulcer. In our research of GAs, the post-ESD bleeding incidence was 4.9%. We must focus on post-ESD bleeding as well as conventional ESD bleeding.

In the introduction stage of ESD, endoscopist has to overcome its technical difficulties and high rates of complication including perforation and bleeding[29,30]. Previous studies[30-32] of learning curves for ESD using knife devices show decreased surgical durations and complication rates and increased rates of successful R0 resections, over time. However, ESD-CC is a simple method that consists of (1) grasping; (2) pulling; and (3) cutting or coagulating, as with a standard bite biopsy. Therefore, we obtained a 100% R0 resection rate and a 0% perforation rate, even at the beginning of the learning curve, because of the ease of learning the ESD-CC procedure, although we were beginners of conventional ESD method using knives. Based on the results of the learning curve analysis, about 30 cases of experience are needed to master the skills to perform ESD-CC for GAs safely and effectively.

In conventional ESD procedures, several specific knives and devices are needed to accomplish the ESD[5-7], whereas ESD-CC was carried out using only the CC. Before introducing ESD-CC into our institute, we performed conventional ESD procedures that required a needle knife for marking and creating the starting hole, an insulation-tipped electrosurgical knife for mucosal incision and submucosal dissection and an electric hemostat for intra-ESD hemorrhage[5-7]. The total number of devices for a single ESD was at least three. In our research, we used only one device, the CC, throughout the ESD. Thus, the ESD-CC significantly reduces the number of devices and the cost of ESD[5,7].

In conclusion, because of its safety, effectiveness of use, technical ease of operation, and low cost of performance, the ESD-CC represents a promising option in the treatment of GAs.

Compared with endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) for early gastric tumors, endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) has considerable advantages with regard to the rates for en-bloc resection, R0 resection and local recurrence. The main shortcoming of ESD using conventional knives is its technical difficulty. Therefore, it has a high rate of complications, and requires advanced endoscopic skills and many devices.

Conventional knife devices gently push the knife to the tissue and cut using electrosurgical current. As these cutting methods lack a grasping function (which would allow more accurate targeting and hemostatic effect) and pulling function (to lift tissues away from the proper muscle layer), they carry a risk of major complications such as perforation and bleeding.

To reduce the risk of complications related to ESD using a conventional knife, Akahoshi and FujiFilm developed a new grasping type of scissor/forceps, the clutch cutter (CC), which can accurately grasp, pull (or lift), coagulate, and/or incise targeted tissue using electrosurgical current. The CC can safely perform four characteristic mechanical procedures: (1) fixation for accurate targeting; (2) pulling or lifting tissue away from the proper muscle layer; (3) compressing tissue through high hemostatic capability; and (4) external insulation, which minimizes risk of unintended electric damage.

The authors performed ESD-CC for 122 patients with gastric adenoma. The en-bloc resection rate was 100% and the R0 resection rate was 100%. No patients in this study suffered perforation. Post-ESD-CC bleeding occurred in 6 cases (4.9%), which were successfully treated by endoscopic hemostatic treatment.

The CC (DP2618DT, FujiFilm Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) is a grasping type of scissor/forceps (VTR. 1), which can grasp and cut or coagulate a piece of tissue with electrosurgical current. It has a 0.4-mm width and a 3.5-mm or 5-mm long serrated cutting edge to facilitate grasping the tissue. The outer side of the forceps is insulated so that electrosurgical current energy is concentrated at the enclosed blade, to avoid unintentional incision. Furthermore, the forceps can be rotated to the desired orientation. The diameter of the forceps is 2.7 mm. The CC is disposable and not reusable. The CC is available for all steps of ESD.

This manuscript “Endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastric adenomas using the clutch cutter” is the nice paper and good results with the CC.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A, A, A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: dos Jácome AA, Farhat S, Imagawa A, Sajid MSS S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Kakushima N, Fujishiro M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastrointestinal neoplasms. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:2962-2967. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lian J, Chen S, Zhang Y, Qiu F. A meta-analysis of endoscopic submucosal dissection and EMR for early gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:763-770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chung IK, Lee JH, Lee SH, Kim SJ, Cho JY, Cho WY, Hwangbo Y, Keum BR, Park JJ, Chun HJ. Therapeutic outcomes in 1000 cases of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric neoplasms: Korean ESD Study Group multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1228-1235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 429] [Cited by in RCA: 476] [Article Influence: 29.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yamamoto Y, Fujisaki J, Ishiyama A, Hirasawa T, Igarashi M. Current status of training for endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric epithelial neoplasm at Cancer Institute Hospital, Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research, a famous Japanese hospital. Dig Endosc. 2012;24 Suppl 1:148-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Akahoshi K, Motomura Y, Kubokawa M, Gibo J, Kinoshita N, Osada S, Tokumaru K, Hosokawa T, Tomoeda N, Otsuka Y. Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection for Early Gastric Cancer using the Clutch Cutter: a large single-center experience. Endosc Int Open. 2015;3:E432-E438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Akahoshi K, Akahane H. A new breakthrough: ESD using a newly developed grasping type scissor forceps for early gastrointestinal tract neoplasms. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;2:90-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Akahoshi K, Akahane H, Motomura Y, Kubokawa M, Itaba S, Komori K, Nakama N, Oya M, Nakamura K. A new approach: endoscopic submucosal dissection using the Clutch Cutter® for early stage digestive tract tumors. Digestion. 2012;85:80-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Akahoshi K, Akahane H, Murata A, Akiba H, Oya M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection using a novel grasping type scissors forceps. Endoscopy. 2007;39:1103-1105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Akahoshi K, Honda K, Akahane H, Akiba H, Matsui N, Motomura Y, Kubokawa M, Endo S, Higuchi N, Oya M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection by using a grasping-type scissors forceps: a preliminary clinical study (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:1128-1133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Goldstein NS, Lewin KJ. Gastric epithelial dysplasia and adenoma: historical review and histological criteria for grading. Hum Pathol. 1997;28:127-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ming SC. Cellular and molecular pathology of gastric carcinoma and precursor lesions: A critical review. Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:31-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nonaka K, Arai S, Ban S, Kitada H, Namoto M, Nagata K, Ochiai Y, Togawa O, Nakao M, Nishimura M. Prospective study of the evaluation of the usefulness of tumor typing by narrow band imaging for the differential diagnosis of gastric adenoma and well-differentiated adenocarcinoma. Dig Endosc. 2011;23:146-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kim JH, Kim YJ, An J, Lee JJ, Cho JH, Kim KO, Chung JW, Kwon KA, Park DK, Kim JH. Endoscopic features suggesting gastric cancer in biopsy-proven gastric adenoma with high-grade neoplasia. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:12233-12240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kamiya T, Morishita T, Asakura H, Miura S, Munakata Y, Tsuchiya M. Long-term follow-up study on gastric adenoma and its relation to gastric protruded carcinoma. Cancer. 1982;50:2496-2503. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Rugge M, Cassaro M, Di Mario F, Leo G, Leandro G, Russo VM, Pennelli G, Farinati F. The long term outcome of gastric non-invasive neoplasia. Gut. 2003;52:1111-1116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Minoda Y, Akahoshi K, Otsuka Y, Kubokawa M, Motomura Y, Oya M, Nakamura K. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early duodenal tumor using the Clutch Cutter: a preliminary clinical study. Endoscopy. 2015;47 Suppl 1 UCTN:E267-E268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Akahoshi K, Okamoto R, Akahane H, Motomura Y, Kubokawa M, Osoegawa T, Nakama N, Chaen T, Oya M, Nakamura K. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early colorectal tumors using a grasping-type scissors forceps: a preliminary clinical study. Endoscopy. 2010;42:419-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Min YW, Min BH, Lee JH, Kim JJ. Endoscopic treatment for early gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:4566-4573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Nakamoto S, Sakai Y, Kasanuki J, Kondo F, Ooka Y, Kato K, Arai M, Suzuki T, Matsumura T, Bekku D. Indications for the use of endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer in Japan: a comparative study with endoscopic submucosal dissection. Endoscopy. 2009;41:746-750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Białek A, Wiechowska-Kozłowska A, Pertkiewicz J, Karpińska K, Marlicz W, Milkiewicz P, Starzyńska T. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for the treatment of neoplastic lesions in the gastrointestinal tract. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:1953-1961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Mannen K, Tsunada S, Hara M, Yamaguchi K, Sakata Y, Fujise T, Noda T, Shimoda R, Sakata H, Ogata S. Risk factors for complications of endoscopic submucosal dissection in gastric tumors: analysis of 478 lesions. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:30-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Watari J, Tomita T, Toyoshima F, Sakurai J, Kondo T, Asano H, Yamasaki T, Okugawa T, Ikehara H, Oshima T. Clinical outcomes and risk factors for perforation in gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection: A prospective pilot study. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;5:281-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ikezawa K, Michida T, Iwahashi K, Maeda K, Naito M, Ito T, Katayama K. Delayed perforation occurring after endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2012;15:111-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hanaoka N, Uedo N, Ishihara R, Higashino K, Takeuchi Y, Inoue T, Chatani R, Hanafusa M, Tsujii Y, Kanzaki H. Clinical features and outcomes of delayed perforation after endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer. Endoscopy. 2010;42:1112-1115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Oda I, Gotoda T, Hamanaka H, Eguchi T, Saito Y, Matsuda T, Bhandari P, Emura F, Saito D, Ono H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: technical feasibility, operation time and complications from a large consecutive series. Dig Endosc. 2005;17:54-58. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 336] [Cited by in RCA: 333] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 26. | Tsuji Y, Ohata K, Ito T, Chiba H, Ohya T, Gunji T, Matsuhashi N. Risk factors for bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric lesions. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:2913-2917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Fujishiro M, Chiu PW, Wang HP. Role of antisecretory agents for gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection. Dig Endosc. 2013;25 Suppl 1:86-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Koh R, Hirasawa K, Yahara S, Oka H, Sugimori K, Morimoto M, Numata K, Kokawa A, Sasaki T, Nozawa A. Antithrombotic drugs are risk factors for delayed postoperative bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric neoplasms. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:476-483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Neuhaus H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection in the upper gastrointestinal tract: present and future view of Europe. Dig Endosc. 2009;21 Suppl 1:S4-S6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Probst A, Golger D, Arnholdt H, Messmann H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early cancers, flat adenomas, and submucosal tumors in the gastrointestinal tract. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:149-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Tanimoto MA, Torres-Villalobos G, Fujita R, Santillan-Doherty P, Albores-Saavedra J, Chable-Montero F, Martin-Del-Campo LA, Vasquez L, Bravo-Reyna C, Villanueva O. Learning curve in a Western training center of the circumferential en bloc esophageal endoscopic submucosal dissection in an in vivo animal model. Diagn Ther Endosc. 2011;2011:847831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Coman RM, Gotoda T, Draganov PV. Training in endoscopic submucosal dissection. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;5:369-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |