Published online Jul 16, 2017. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v9.i7.296

Peer-review started: December 23, 2016

First decision: February 4, 2017

Revised: March 22, 2017

Accepted: June 12, 2017

Article in press: June 13, 2017

Published online: July 16, 2017

Processing time: 196 Days and 21.5 Hours

To assess incidence of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (post-ERCP) pancreatitis in the early (July/August/September) vs the late (April/May/June) academic year and evaluate in-hospital mortality, length of stay (LOS), and total hospitalization charge between these time periods.

This was a retrospective cohort study using the 2012 Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS). Patients with International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9 CM) procedure codes for ERCP were included. Patients were excluded from the study if they had an ICD-9 CM code for a principal diagnosis of acute pancreatitis, if the ERCP was performed before or on the day of admission or if they were admitted to non-teaching hospitals. Post-ERCP pancreatitis was defined as an ICD-9 CM code for a secondary diagnosis of acute pancreatitis in patients who received an ERCP as delineated above. ERCPs performed during the months of July, August and September was compared to those performed in April, May and June in academic hospitals. ERCPs performed at academic hospitals during the early vs late year were compared. Primary outcome was incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Secondary outcomes included in-hospital mortality, length LOS, and total hospitalization charge. Proportions were compared using fisher’s exact test and continuous variables using student t-test. Multivariable regression was performed.

From the 36480032 hospitalizations in 2012 in the United States, 6248 were included in the study (3065 in July/August/September and 3183 in April/May/June) in the 2012 academic year. Compared with patients admitted in July/August/September, patients admitted in April/May/June had no statistical difference in all variables including mean age, percent female, Charleston comorbidity index, race, median income, and hospital characteristics including region, bed size, and location. Incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis in early vs late academic year were not statistically significant (OR = 1.03, 95%CI: 0.71-1.51, P = 0.415). Similarly, the adjusted odds ratio of mortality, LOS, and total hospitalization charge in early compared to late academic year were not statistically significant.

Incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis does not differ at academic institutions depending on the time of year. Similarly, mortality, LOS, and total hospital charge do not demonstrate the existence of a temporal effect, suggesting that trainee level of experience does not impact clinical outcomes in patients undergoing ERCP.

Core tip: The changeover of medical trainees has been shown to negatively impact patient care. At academic institutions, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) involves advanced endoscopy fellows, and outcomes may vary based on the time of year. We assessed the incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis in the early vs the late academic year and evaluated in-hospital mortality, length of stay (LOS), and total hospitalization charge between these time periods. We found that the incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis in early vs late academic year were not statistically significant. Furthermore, mortality, LOS, and total hospitalization charge in early compared to late academic year were not statistically significant.

- Citation: Schulman AR, Abougergi MS, Thompson CC. Assessment of the July effect in post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis: Nationwide Inpatient Sample. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2017; 9(7): 296-303

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v9/i7/296.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v9.i7.296

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is frequently used for the diagnosis and management of many biliary and pancreatic diseases. Pancreatitis is the most common and serious complication of ERCP, accounting for more than half of all complications following this procedure[1-3]. The estimated incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP) varies substantially and is reported to be between 1% to 15%, with select studies reporting incidences as high as 30% in some populations[4,5]. While the majority of PEP is mild, up to 20% of reported cases are moderate or severe[6], and in some instances even fatal[4]. In a small number of patients, it can lead to prolonged hospitalizations, anatomical complications such as bile duct or duodenal obstruction, pseudoaneurysms, and psuedocysts, as well as a significant financial burden to hospitals[7].

The changeover of medical trainees at the beginning of the academic year has been shown in a variety of settings to negatively impact the quality of patient care, an observation referred to as the “July effect”[8-10]. Although results have been substantially variable across studies addressing the July effect, most large and high-quality studies find a relatively small but statistically significant increase in mortality at the start of the academic year across multiple medical conditions[10-14]. Furthermore, numerous studies have demonstrated decreased efficiency in healthcare delivery during turnover months in teaching hospitals as demonstrated by increased length of hospital stay (LOS) and increased mean total hospitalization charges[15-19].

At teaching institutions, ERCP involves the participation of advanced endoscopy fellows who are trainees with minimal experience with this procedure, especially at the commencement of the academic year. These fellows are expected to gradually gain mastery and independence in performing ERCP. This learning curve is particularly relevant since several studies have shown that a number of endoscopic technique-related factors predict the occurrence of PEP. For example, papillary trauma induced by multiple attempts at cannulation was reported to be an independent risk factor for development of this complication in a large, prospective, multicenter study[20]. Furthermore, multiple pancreatic injections and pancreatic duct instrumentation have also been identified as factors that independently increase the risk of PEP[21].

These findings support the fact that physician technique, expertise, and experience may play a role in the occurrence of PEP. Consequently, outcomes may vary based on the time of year during which the procedure is performed. Specifically, the incidence of PEP may decrease at the end of the academic year when the advanced endoscopy fellows are more seasoned and possess enhanced procedural skills.

Large national databases are ideal resources for addressing such clinical questions because they contain sufficient data to overcome participation and reporting biases, and the results are readily generalizable. We used the National Inpatient Sample (NIS), the largest publically available all-payer inpatient database in the United States. The primary aim of the current study is to assess incidence of PEP among hospitalized patients in the early (July/August/September) vs the late (April/May/June) academic year. Secondary aims assess in-hospital mortality, length of stay (LOS), and total hospitalization charges between these time periods.

This was a retrospective cohort study using the 2012 National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database. This database was created and is maintained by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. It is the largest publically available all-payer inpatient database in the United States. The NIS is designed as a stratified probability sample to be representative of all non-federal acute care inpatient hospitalizations in the United States. Briefly, hospitals are stratified according to ownership/control, bed size, teaching status, urban/rural location, and geographic region. A random 20% sample of all discharges from all participating hospitals within each stratum is then collected and information about patients’ demographics, diagnoses, resource utilization including length of hospital stay, procedures and total hospitalization charges are entered into the NIS. Each discharge is then weighted (weight is equal to the total number of discharges from all acute care hospital in the United States divided by the number of discharges included in the 20% sample) to make the NIS nationally representative. In 2012, the NIS included 7296968 discharges from 4378 hospitals in 44 states.

The NIS contains both patient and hospital level information. Up to 25 discharge diagnoses and 15 procedures are collected on each patient using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9 CM) coding system. The NIS has been used to provide reliable estimates of the burden of gastrointestinal diseases[22,23].

Patients were included in the study if they had an ICD-9 CM procedure codes for ERCP. Patients were excluded from the study if they had an ICD-9 CM code for a principal diagnosis of acute pancreatitis, if the ERCP was performed before or on the day of admission or if they were admitted to non-teaching hospitals. Post-ERCP pancreatitis was defined as an ICD-9 CM code for a secondary diagnosis of acute pancreatitis in patients who received an ERCP as delineated above. ERCPs performed during the months of July, August and September was compared to those performed in April, May and June in academic hospitals.

Admission month, vital status at discharge, length of hospital stay and total hospitalization charges are directly provided in the NIS for each hospitalization. Patient demographics collected are: Age (assessed as a continuous variable), sex, race (Caucasian, African American, Hispanic, Asian or Pacific Islander, native American and other), median income in the patient’s zip code (Quartile 1: $1-$38999; Quartile 2: $39000-$47999; Quartile 3: $48000-$63999; quartile 4: $64000+), primary insurance (Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance and uninsured), comorbidities measured by Charlson comorbidity index (categorized as 0, 1 to 2, or greater than 2), hospital location (rural vs urban), region (Northeast, Midwest, West, or South), teaching status, and size (small, medium or large). Patients’ demographics were directly provided in the NIS except for Charlson comorbidity index which was calculated for each patient using the Deyo adaptation of the Charlson comorbidity Index for administrative data[24].

The primary outcome was incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Secondary outcomes were: All cause in-hospital mortality, length of hospital stay (LOS) and total hospitalization charges for patients who developed PEP.

Proportions were compared using Fisher’s exact test and continuous variables were compared using Student’s t-test (under the assumption of the Central Limit Theorem). Confounders were adjusted for using multivariable regression models. Linear regression was used for continuous outcomes and logistic regression was used for binary outcomes. Each model was constructed by including all variables that were statistically significantly associated with the outcome on univariate analysis with a cutoff P-value of 0.2. In addition, variables that were considered clinically important predictors of the outcome based on prior studies’ findings were included in the models irrespective of the P-value on univariate analysis. Patients with missing information on any of the variables included in the regression analyses were excluded.

All analyses were performed using STATA version 13 (STATACorpLP, College Station, TX, United States). Survey (svy) commands were used to account for the stratified sampling design of the NIS. A two tailed P-value of 0.05 was chosen as the threshold for significance for all tests.

The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Marwan Abougergi from Catalyst Medical Consulting.

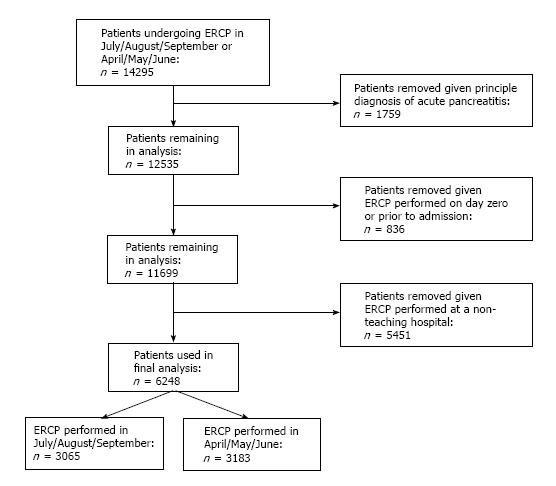

Figure 1 shows the flow diagram for study inclusion. From the 36480032 hospitalizations in 2012 in the United States, 6248 were included in the study (3065 in July/August/September and 3183 in April/May/June) in the 2012 academic year. Patient’s characteristics are presented in Table 1. Compared with patients admitted in July/August/September, patients admitted in April/May/June had no statistical difference in all variables including mean age, percent female, Charleston comorbidity index, race, median income, and hospital characteristics including region, bed size, and location.

| Variable | July/August/September | April/May/June |

| Total number of ERCPs | 3065 | 3183 |

| Post-ERCP pancreatitis | 404 (13.2) | 402 (12.6) |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 58.9 ± 0.8 | 59.5 ± 0.9 |

| Female | 1672 (54.6) | 1617 (50.8) |

| Charleston Comorbidity Score | ||

| 0 | 190 (6) | 131 (4) |

| 1-2 | 490 (16) | 550 (17) |

| > 2 | 2385 (78) | 2503 (79) |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 1834 (64) | 1967 (66) |

| African American | 395 (14) | 441 (15) |

| Hispanic | 411 (14) | 311 (11) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 123 (4) | 96 (3) |

| Native American | 15 (1) | 23 (1) |

| Other | 98 (3) | 130 (4) |

| Median income ($) in zip code | ||

| 1-38999 | 836 (28) | 865 (28) |

| 39000-47999 | 636 (22) | 688 (22) |

| 48000-63999 | 726 (24) | 845 (27) |

| 64000+ | 819 (27) | 732 (23) |

| Hospital region | ||

| Northeast | 791.8 (26) | 819.5 (26) |

| Midwest | 679.2 (22) | 918.1 (29) |

| South | 997.6 (33) | 925.5 (29) |

| West | 596.9 (19) | 520.4 (16) |

| Hospital bed size | ||

| Small | 293.2 (10) | 343.3 (10) |

| Medium | 680.2 (22) | 728 (23) |

| Large | 2092 (68) | 2112 (67) |

| Hospital location | ||

| Rural | 43.2 (1) | 20.4 (1) |

| Urban | 3022 (99) | 3163 (99) |

The overall post-ERCP pancreatitis incidence was 12.9%. Table 2 shows the post-ERCP pancreatitis incidence based on time of the academic year, as well as the adjusted odds ratio of PEP. Compared with patients admitted in July/August/September, patients admitted in April/May/June had similar odds of developing PEP after adjusting for confounders (adjusted OR = 1.03, 95%CI: 0.71-1.51; P = 0.41).

| Incidence n (%) | Adjusted OR (95%CI) | P value | ||

| July/August/September | ERCPs performed | 3065 | 1.03 (0.71-1.51) | 0.415 |

| Post-ERCP Pancreatitis rates | 404 (13.2) | |||

| April/May/June | ERCPs performed | 3183 | ||

| Post-ERCP Pancreatitis rates | 402 (12.6) | |||

The overall mortality rate following PEP was 19/801 = 2.37%. Table 3 shows the mortality rate following post-ERCP pancreatitis based on time of the academic year along with the mortality adjusted odds ratio. The adjusted odds of mortality following PEP was similar in in April/May/June compared with July/August/September (adjusted OR = 33.2, 95%CI: 0.55-1980.7; P = 0.09).

| Mortality | Adjusted OR (95%CI) | P value | ||

| n/total | % | |||

| July/August/September | 5/404 | 1.24 | 33.2 (0.55-1980.7) | 0.092 |

| April/May/June | 14/402 | 3.48 | ||

Following PEP, the overall LOS was 10.48 d. The mean adjusted LOS following post-ERCP pancreatitis based on time of the academic year along with the mean additional LOS for patients admitted in July/August/September compared with April/May/June are shown in Table 4. The adjusted mean LOS following PEP was similar in July/August/September compared with April/May/June, with an adjusted mean difference of 2.04 d, 95%CI: -0.76 to 4.84; P = 0.15.

| Length of stay | Total charges | |||

| Mean (95%CI) (d) | P value | Mean (95%CI) ($) | P value | |

| July/August/September | 10.6 (8.5-12.7) | 0.91 | 101904 (78785-125023) | 0.938 |

| April/May/June | 10.4 (8.2-12.6) | 100519 (70214-130824) | ||

The mean adjusted total hospitalization charges for patients who developed PEP was $101218. The mean total hospitalization charges among patients who developed PEP in July/August/September and April/May/June are shown in Table 4. The adjusted mean total hospitalization charges were similar in July/August/September compared with April/May/June: $20990, 95%CI: -563210 to 1434; P = 0.24.

This large nationwide study found no difference in incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis following in-hospital ERCP at academic institutions over the course of the academic year. To our knowledge, this study is the first to address the presence, or lack thereof, of a July effect in the incidence and treatment of post-ERCP pancreatitis following in-hospital ERCP. It is also among the few studies that measures the PEP incidence rate after in-hospital ERCP. Our findings suggest that close supervision by attending endoscopists in the academic inpatient setting mitigates potential risks incurred by novice advanced endoscopy fellows, as evidenced by similar PEP adjusted incidence across the academic year.

Whether these results are also true for PEP following outpatient ERCP is still controversial. Several smaller previous studies have sought to determine whether a difference in outcomes exists between ERCP that involves trainees and those that do not, and results have been inconsistent. The study by Freeman et al was among the first prospective studies investigating trainee participation in ERCP. Specifically, the authors measured the complications that occurred within 30 d of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy in consecutive patients treated at 17 institutions over a two year period[20]. The study failed to show an increased risk of adverse events including pancreatitis due the presence of a trainee. Subsequently, Rabenstein et al[25] sought to analyze the risk factors associated with complications of endoscopic sphincterotomy in a series of 436 consecutive patients. While several independent risk factors for the development of PEP were identified, trainee involvement did not significantly affect the outcome. However, more recently, Cheng et al[26] found that trainee involvement did increase the risk of PEP, and was attributed to a variety of procedural-related factors including traumatic cannulation, prolonging a difficult cannulation, and delivering excess electrosurgical current during sphincterotomy.

Our data suggest that the overall efficiency of the hospital, similar to mortality rate, does not seem to exhibit a temporal effect. LOS and total hospital charge were not significantly increased at the beginning of the academic year, suggesting no effect on adeptness during turnover months at teaching hospitals. It is important to note that, since the number of patients who died following PEP was very low, the lack of difference in mortality at the beginning and the end of the academic year could be either due to a beta error or a true lack of difference. Case-control studies or cohort studies combining patients from the NIS over several years could help distinguish between these two possibilities. However, combining patients over several years has its own limitations, including the inherent necessity to adopt the assumption that time is not a significant confounder in the relationship between PEP and mortality.

Several previous studies have examined length of hospital stay and hospitalization charge for a broad range of admission diagnosis as a marker for the July effect, and conflicting conclusions have been reached. In one multicenter retrospective study, LOS in the intensive care unit was examined and, after adjusting for illness severity, no differences in LOS were found between early and late academic year[15]. Similarly, a single center study analyzing hospital LOS and ancillary charges in over 2700 patients admitted for any condition over a two year period found no evidence of a temporal effect[27]. In contrast, a study in a single institution over seven years demonstrated a significant and steady decline in both total hospital charge and LOS for a variety of diagnoses over the academic year[16]. For each additional month of house staff experience, total charges declined by approximately 0.94% in total charges, or about 11% during a one-year period. Furthermore, for each additional month of house staff experience, there was a 0.036-d decline in length of hospital stay, leading to a 0.43-d reduction during a one-year period.

Inexperienced fellow involvement in ERCP procedures has clear implications for patient outcomes, with the potential to lead to increased complications and higher medical expenditures. Our results, however, do not suggest that this is the case. We have demonstrated the lack of existence of a July effect. Novice fellow participation in these procedures at the beginning of the academic year does not seem to be associated with worse patient outcomes or increased charges compared to late academic year, when trainees have substantially more procedural experience. To clarify, these results do not suggest that novice endoscopists can safely perform ERCP in an unsupervised setting. However, the results of this study show that our current training method allows for the safe development of ERCP skills in a clinical setting, with close supervision from expert endoscopists.

Our study has several strengths. NIS is one of the largest medical databases in the United States, which allows for the analysis of health care practice patterns at the national level. Selection and participation biases, as well as regional variations in healthcare delivery and medical practice which commonly limit smaller studies, are minimized given that the sample is taken from a broad range of patient demographics and hospital characteristics from almost every state. Furthermore, the generalizability of the results to different hospitals and regions of the United States is tremendously enhanced for the same reason.

There are also several limitations of our study. First, some academic institutions may not have gastroenterology and/or advanced endoscopy fellowships, possibly diluting any effect that may be attributable to the involvement of a trainee. However, since caring for patients with PEP is a multi-disciplinary approach, this fact should not have had a major impact on our outcomes, with the possible exception being PEP incidence. Second, there is no ICD-9 CM code specific for PEP pancreatitis. The definition we adopted (secondary diagnosis of pancreatitis for admissions during which ERCP was performed) could potentially include patients who had ERCP because of acute pancreatitis. However, we minimized this possibility by excluding patients who had a principal diagnosis of acute pancreatitis and limiting the inclusion to patients who had ERCP on day 1 of admission. Third, the severity of PEP is difficult to ascertain using ICD-9 codes, which lead us to restrict treatment outcomes to mortality only. Fourth, despite controlling for confounders and hospital characteristics, residual confounding is an inherent limitations to all retrospective studies where randomization is impossible. Fifth, while these results are compelling given the number of patients included in this database, we are unable to assess whether differences in technique affected PEP rates in this study. The NIS database does not allow the ability to control for factors that may affect the incidence of PEP but do not have a discrete ICD-9 code including inadvertent cannulation of the pancreatic duct, time until successful cannulation, use of sphincterotomy, degree of supervision by attending physician, and so on. Additionally, the database does not reveal the number of ERCPs performed for biliary vs pancreatic indications. Finally, coding errors have been shown to exist in the NIS data[28]. However, such errors are theoretically randomly distributed among patients who had PEP early vs late in the academic year and therefore should not be a source of bias.

In conclusion, the safety of ERCP at academic institutions is consistent over the course of the year, with no difference in incidence or mortality following post-ERCP pancreatitis. Similarly, outcomes of healthcare delivery in the treatment of PEP are also steady across the academic year, as evidenced by similar LOS and total hospital charges. Our results suggest that trainee level of experience does not impact clinical outcomes in patients undergoing ERCP. As we train the next generation of endoscopic proceduralists, efforts to continue graduated responsibility, while maintaining optimal patient outcomes, will remain a top priority in the field of therapeutic endoscopy.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is frequently used for the diagnosis and management of many biliary and pancreatic diseases. Pancreatitis is the most common and serious complication of ERCP. At teaching institutions, ERCP involves the participation of advanced endoscopy fellows who are trainees with minimal experience with this procedure, especially at the commencement of the academic year. As the changeover of medical trainees at the beginning of the academic year has been shown in a variety of settings to negatively impact the quality of patient care, an observation referred to as the July effect, they sought to determine whether a July effect existed with ERCP.

The authors sought to determine whether a “July effect” existed with ERCP in academic hospitals.

This large nationwide study found no difference in incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis following in-hospital ERCP at academic institutions over the course of the academic year. To the knowledge, this study is the first to address the presence, or lack thereof, of a July effect in the incidence and treatment of post-ERCP pancreatitis following in-hospital ERCP.

These findings suggest that close supervision by attending endoscopists in the academic inpatient setting mitigates potential risks incurred by novice advanced endoscopy fellows, as evidenced by similar PEP adjusted incidence across the academic year. These results do not suggest that novice endoscopists can safely perform ERCP in an unsupervised setting. However, the results of this study show that the current training method allows for the safe development of ERCP skills in a clinical setting, with close supervision from expert endoscopists.

ERCP is frequently used for the diagnosis and management of many biliary and pancreatic diseases. Pancreatitis is the most common and serious complication of ERCP, accounting for more than half of all complications following this procedure. This is referred to as post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP).

This is a valuable paper, objectively reflects the incidence of PEP, and reveals no relationship with the beginner.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Jagielski M, Kawaguchi Y, Sharma SS, Tomizawa M, Yin HK S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Abdel Aziz AM, Lehman GA. Pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2655-2668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Freeman ML, DiSario JA, Nelson DB, Fennerty MB, Lee JG, Bjorkman DJ, Overby CS, Aas J, Ryan ME, Bochna GS. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: a prospective, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:425-434. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Christensen M, Matzen P, Schulze S, Rosenberg J. Complications of ERCP: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:721-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 305] [Cited by in RCA: 299] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Dumonceau JM, Riphaus A, Aparicio JR, Beilenhoff U, Knape JT, Ortmann M, Paspatis G, Ponsioen CY, Racz I, Schreiber F. European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, European Society of Gastroenterology and Endoscopy Nurses and Associates, and the European Society of Anaesthesiology Guideline: Non-anaesthesiologist administration of propofol for GI endoscopy. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2010;27:1016-1030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Freeman ML, Guda NM. Prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a comprehensive review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:845-864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 321] [Cited by in RCA: 316] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, Geenen JE, Russell RC, Meyers WC, Liguory C, Nickl N. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:383-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hauser G, Milosevic M, Stimac D, Zerem E, Jovanović P, Blazevic I. Preventing post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis: what can be done? World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:1069-1080. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Haller G, Myles PS, Taffé P, Perneger TV, Wu CL. Rate of undesirable events at beginning of academic year: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2009;339:b3974. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Barzansky B, Etzel SI. Medical schools in the United States, 2007-2008. JAMA. 2008;300:1221-1227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Young JQ, Ranji SR, Wachter RM, Lee CM, Niehaus B, Auerbach AD. “July effect”: impact of the academic year-end changeover on patient outcomes: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:309-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 263] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Anderson KL, Koval KJ, Spratt KF. Hip fracture outcome: is there a “July effect”? Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2009;38:606-611. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Shuhaiber JH, Goldsmith K, Nashef SA. Impact of cardiothoracic resident turnover on mortality after cardiac surgery: a dynamic human factor. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86:123-130; discussion 130-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jen MH, Bottle A, Majeed A, Bell D, Aylin P. Early in-hospital mortality following trainee doctors’ first day at work. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Phillips DP, Barker GE. A July spike in fatal medication errors: a possible effect of new medical residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:774-779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Barry WA, Rosenthal GE. Is there a July phenomenon? The effect of July admission on intensive care mortality and length of stay in teaching hospitals. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:639-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rich EC, Gifford G, Luxenberg M, Dowd B. The relationship of house staff experience to the cost and quality of inpatient care. JAMA. 1990;263:953-957. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bakaeen FG, Huh J, LeMaire SA, Coselli JS, Sansgiry S, Atluri PV, Chu D. The July effect: impact of the beginning of the academic cycle on cardiac surgical outcomes in a cohort of 70,616 patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:70-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Dhaliwal AS, Chu D, Deswal A, Bozkurt B, Coselli JS, LeMaire SA, Huh J, Bakaeen FG. The July effect and cardiac surgery: the effect of the beginning of the academic cycle on outcomes. Am J Surg. 2008;196:720-725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Rich EC, Hillson SD, Dowd B, Morris N. Specialty differences in the ‘July Phenomenon’ for Twin Cities teaching hospitals. Med Care. 1993;31:73-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, Moore JP, Fennerty MB, Ryan ME, Shaw MJ. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1716] [Cited by in RCA: 1687] [Article Influence: 58.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 21. | Ding X, Zhang F, Wang Y. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgeon. 2015;13:218-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Go JT, Vaughan-Sarrazin M, Auerbach A, Schnipper J, Wetterneck TB, Gonzalez D, Meltzer D, Kaboli PJ. Do hospitalists affect clinical outcomes and efficiency for patients with acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage (UGIH)? J Hosp Med. 2010;5:133-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wolf AT, Wasan SK, Saltzman JR. Impact of anticoagulation on rebleeding following endoscopic therapy for nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:290-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7532] [Cited by in RCA: 8640] [Article Influence: 261.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Rabenstein T, Schneider HT, Bulling D, Nicklas M, Katalinic A, Hahn EG, Martus P, Ell C. Analysis of the risk factors associated with endoscopic sphincterotomy techniques: preliminary results of a prospective study, with emphasis on the reduced risk of acute pancreatitis with low-dose anticoagulation treatment. Endoscopy. 2000;32:10-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Cheng CL, Sherman S, Watkins JL, Barnett J, Freeman M, Geenen J, Ryan M, Parker H, Frakes JT, Fogel EL. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: a prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:139-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 414] [Cited by in RCA: 433] [Article Influence: 22.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Buchwald D, Komaroff AL, Cook EF, Epstein AM. Indirect costs for medical education. Is there a July phenomenon? Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:765-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Berthelsen CL. Evaluation of coding data quality of the HCUP National Inpatient Sample. Top Health Inf Manage. 2000;21:10-23. [PubMed] |