Published online May 16, 2017. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v9.i5.228

Peer-review started: December 26, 2016

First decision: February 4, 2017

Revised: February 24, 2017

Accepted: March 23, 2017

Article in press: March 24, 2017

Published online: May 16, 2017

Processing time: 156 Days and 6.8 Hours

To investigate the role of music in reducing anxiety and discomfort during flexible sigmoidoscopy.

A systematic review of all comparative studies up to November 2016, without language restriction that were identified from MEDLINE and the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register (1960-2016), and EMBASE (1991-2016). Further searches were performed using the bibliographies of articles and abstracts from major conferences such as the ESCP, NCRI, ASGBI and ASCRS. MeSH and text word terms used included “sigmoidoscopy”, “music” and “endoscopy” and “anxiety”. All comparative studies reporting on the effect of music on anxiety or pain during flexible sigmoidoscopy, in adults, were included. Outcome data was extracted by 2 authors independently using outcome measures defined a priori. Quality assessment was performed.

A total of 4 articles published between 1994 and 2010, fulfilled the selection criteria. Data were extracted and analysed using OpenMetaAnalyst. Patients who listened to music during their flexible sigmoidoscopy had less anxiety compared to control groups [Random effects; SMD: 0.851 (0.467, 1.235), S.E = 0.196, P < 0.001]. There was no statistically significant heterogeneity (Q = 0.085, df = 1, P = 0.77, I2 = 0). Patients who listened to music during their flexible sigmoidoscopy had less pain compared to those who did not, but this difference did not reach statistical significance [Random effects; SMD: 0.345 (-0.014, 0.705), S.E = 0.183, P = 0.06]. Patients who listened to music during their flexible sigmoidoscopy felt it was a useful intervention, compared to those who did not (P < 0.001). There was no statistically significant heterogeneity (P = 0.528, I2 = 0).

Music appeared to benefit patients undergoing flexible sigmoidoscopies in relation to anxiety and was deemed a helpful intervention. Pain may also be reduced however further investigation is required to ascertain this.

Core tip: The use of flexible sigmoidoscopy is becoming more prevalent particularly in the context of bowel cancer screening; however uptake remains low and patients are often anxious when attending about discomfort and embarrassment. We conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies investigating the role of music in reducing anxiety and discomfort in patients undergoing screening flexible sigmoidoscopy. In our review, music reduced anxiety and was deemed a helpful intervention by the patients. It may also reduce discomfort but further studies are required to confirm this. Music may potentially improve patient experience and have a positive effect on the test uptake.

- Citation: Shanmuganandan AP, Siddiqui MRS, Farkas N, Sran K, Thomas R, Mohamed S, Swift RI, Abulafi AM. Does music reduce anxiety and discomfort during flexible sigmoidoscopy? A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2017; 9(5): 228-237

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v9/i5/228.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v9.i5.228

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer diagnosed amongst men, and second amongst women. It is the fourth common cause of cancer deaths[1]. The United Kingdom Flexible Sigmoidoscopy Trial demonstrated that a once only flexible sigmoidoscopy screening between ages 55 and 64[2], significantly reduced the incidence of colorectal cancers and cancer-related mortality from the disease. Following this study, screening using flexible sigmoidoscopy was piloted across six centers in England, inviting anyone aged 55 years to undergo screening. The uptake was 43% (45% in men and 42% in women, 33% in low socioeconomic areas)[3]. A Study on patient attitudes towards screening flexible sigmoidoscopy (FS) showed as possible reasons for poor uptake to be embarrassment and concern regarding pain during the procedure[4]. Anxiety is also thought to be an important factor that may deter patients undergoing screening FS[5].

Given the benefit of FS screening, techniques designed to improve patient tolerance without increasing costs may lead to an increase in uptake. Methods such as distraction have previously been used as cost-effective and noninvasive interventions to alleviate acute and chronic pain[6]. It would therefore be useful to see if distraction techniques such as music can be used to reduce anxiety and pain in patients undergoing flexible sigmoidoscopy.

Music has been shown to modulate activity in parts of the brain that control emotions[7,8], and modulate the dopaminergic systems of the brain[9,10]. The association between music and emotions is complex and can be explained by a series of mechanisms including brain stem reflexes, musical expectancy and contagion[11]. A meta-analysis by Lee found music to be an effective complimentary adjunct, for pain and discomfort in different scenarios like acute or chronic pain, during procedures and cancer[12]. Cepeda et al[13] agreed that music can reduce pain intensity and requirements for analgesia, but suggested that the size of these effects was small.

Music has been shown to reduce anxiety levels in patients who have had acute myocardial infarction[14]. In promoting relaxation and diverting attention from anxiety or painful stimuli[5] music has been utilized as a tool to improve user experience in sectors like hospitality, through a positive perceptual experience. Music as a therapy is regarded as one of the most effective distraction techniques with high level of patient compliance[15], because it introduces a competing sensory stimulus, which alters the cognitive perception of pain.

This article focuses on the role of music on anxiety, pain scores and helpfulness during flexible sigmoidoscopy. Our primary hypothesis was that music results in lower post-procedural anxiety compared to those who do not listen to music in the endoscopy room. Secondary hypotheses were: (1) that there is less pain in the music group; and (2) patients find music helpful during their procedure. Anxiety and pain were assessed using a continuous scale whilst helpfulness was a binary outcome.

The title, methods and outcome measures were stipulated in advance and the protocol is available in the PROSPERO database[16].

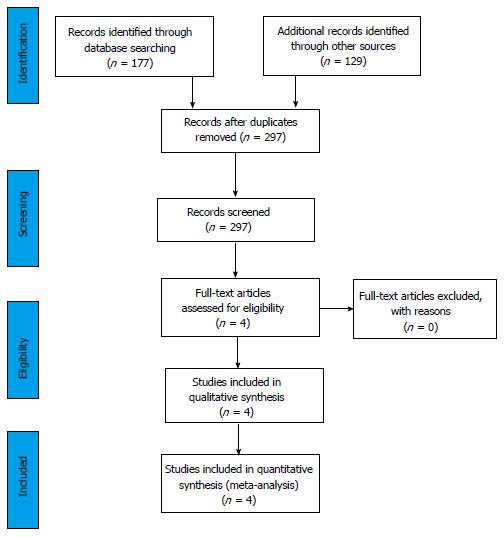

We searched the MEDLINE, EMBASE and CINAHL databases available through the NHS National Library of Health website, the Cochrane library and PubMed available online, up to November 2016. There was no language restriction. Text words “music”, “melody”, “opera”, “classical music”, “distraction”, “flexible sigmoidoscopy”, “anxiety”, “screening” and “endoscopy” were used in combination with the medical subject heading “sigmoidoscopy” and “music”. Relevant articles referenced in these publications were obtained and the references of identified studies were searched to identify any further studies. A flow chart of the literature search according to PRISMA guidelines is shown in Figure 1[17].

We identified and selected all comparative studies reporting the use of any type of music in adult patients of any age or gender undergoing flexible sigmoidoscopy. No regional restriction was placed. No language or publication date restriction was used. Studies that reported on anxiety, pain or usefulness of music during procedure irrespective of assessment methods used were included (Table 1). Studies, which used post-procedure questionnaires assessing whether patients found music helpful, were also included. Each included article was reviewed by two researchers (MRSS and APS). This was performed independently and where more specific data or missing data was required the authors of manuscripts were contacted. Data was entered onto an Excel worksheet and compared between authors. Any disagreements that arose between the reviewers were resolved through discussion and if no consensus could be reached, a third senior author would decide.

| All studies reporting on music therapy during flexible sigmoidoscopy |

| All comparative studies using any control |

| All study designs, adults of any sex and any languages |

Patient demographics and study characteristics were extracted from the relevant studies. The study characteristics included were country of origin, year, music selection and study type. Patient demographics included total number of patients, age and gender (Tables 2 and 3).

| Ref. | Year | From | Types of music used | Control population | Study population | ||||

| n | Age (mean) | Sex (m/f) | n | Age (mean) | Sex (m/f) | ||||

| Palakanis et al[5] | 1994 | United States | Pt selected from classical, country western, popular, gospel music, blues | 25 | 49 | 20/5 | 25 | 55 | 17/8 |

| Lembo et al[6] | 1998 | United States | Ocean shore sounds | 12 | 59 | 12/0 | 12 | 60 | 12/0 |

| Chlan et al[15] | 1999 | United States | Pt selected from classical, country-western, new-age, pop, rock, religious, soundtracks, jazz | 34 | ND | ND | 30 | ND | ND |

| Meeuse et al[22] | 2010 | Europe | Pt selected from classical, English/dutch popular, jazz | 154 | 51 | 72/82 | 153 | 53 | 75/78 |

| Ref. | Year | Group | n | State anxiety score STAI (post procedure) | Anxiety score after SSR | Pain score | Helpful (n) | |||

| Score | SD/SEM | Score | SD/SEM | Score | SD/SEM | |||||

| Palakanis et al[5] | 1994 | Control | 25 | 31.48 | 6.7 | - | - | - | - | 11 |

| Music | 25 | 25.24 | 6.7 | - | - | - | - | 22 | ||

| Lembo et al[6] | 1998 | Control | 12 | - | - | 4.4 | 0.6 | 10.8 | 1.6 | - |

| Music | 12 | - | - | 2.8 | 0.4 | 9.5 | 1.3 | - | ||

| Chlan et al[15] | 1999 | Control | 34 | 41.8 | 9 | - | - | 5.2 | 1.7 | 19 |

| Music | 30 | 34.5 | 9 | - | - | 4.3 | 2.1 | 25 | ||

| Meeuse et al[22] | 2010 | Control | 154 | - | - | - | - | 40 | 29 | - |

| Music | 153 | - | - | - | - | 36 | 27 | - | ||

Statistical analyses were performed using OpenMetaAnalyst (http://www.cebm.brown.edu/openmeta)[18]. Conventional comparative meta-analytical techniques were used. For comparative outcomes, a value of P < 0.05 was chosen as the significance level for outcome measures. Binary data was summarized using risk ratios (RR) and combined using the Mantel-Haenszel method for fixed effects and the DerSimonian and Laird method in the random effects model[19]. For continuous data (anxiety and pain scores), Hedges g statistic was used for the calculation of standardized mean differences (SMD). The SMDs were combined using inverse variance weights in the fixed effects model and the DerSimonian and Laird method in the random effects model[19]. Heterogeneity of the studies was assessed according to Q and I2. A random effects method was used due to presence of clinical heterogeneity. In a sensitivity analysis, 0.5 was added to each cell frequency for trials in which no event occurred, according to the method recommended by Deeks et al[20]. Forest plots were used for the graphical display. The statistical methods used were reviewed by MRS Siddiqui, PhD Research Fellow at The Royal Marsden Hospital NHS Trust and Croydon University Hospital, London, United Kingdom.

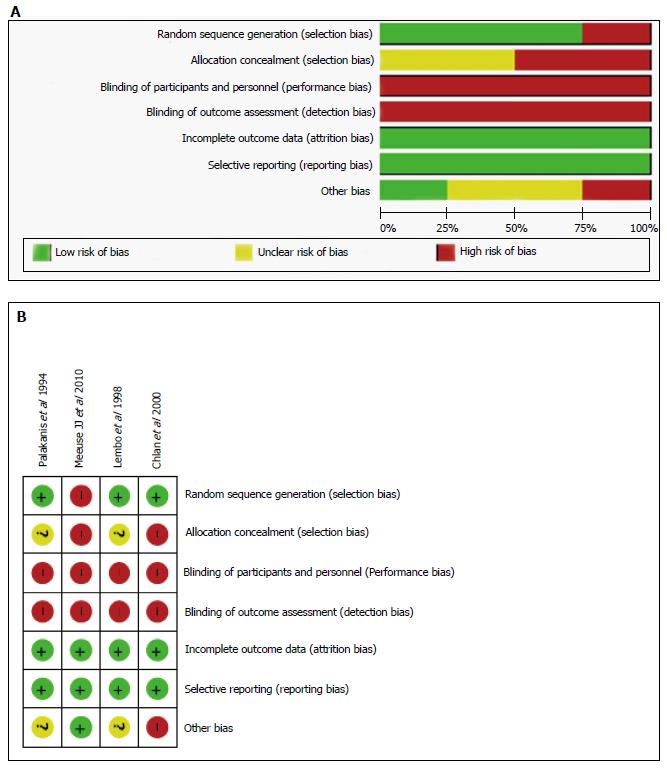

The methodological quality of the trials included for meta-analysis was assessed using the risk of bias tool available from Revman Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014)[21]. Authors performed assessment independently (Muhammed R S Siddiqui and Arun P Shanmuganandan) (Figure 2). There were insufficient studies to perform a meta-regression according to music type, patient age and gender. Furthermore, we could not formally assess for publication bias due to the low number of studies although this may imply inherent bias highlighting the need for further studies.

Three hundred and six articles were screened for relevance (Figure 1). The electronic databases searched (Medline, Cochrane, EmBase) yielded 177 records and in addition 129 citations were identified through bibliographies and conference proceedings. After removal of duplicates 297 unique records were left. Records were excluded if they were deemed irrelevant or not related to the study. On further scrutiny, 4 studies[5,6,15,22] reported on outcomes after music during flexible sigmoidoscopy in respect to anxiety, pain scores and whether it was deemed helpful. These studies were chosen based on our inclusion criteria (Table 1). There was no data from any unpublished or grey literature.

The characteristics of the 4 studies included are summarised in Table 2. All 4 studies[5,6,15,22] were published in English. Three studies were carried out in the United States[5,6,15] and one[22] in Europe. All studies were comparative, 3 used randomized allocation, but no blinding. None of the patients received sedation. 3 studies offered patients a choice of music from collections of a variety of styles of music like jazz, classical, country-western, blues, gospel music, pop and rock, while in the fourth study[6], patients listened to ocean shore sounds.

A total of 445 patients were included in this review. Of the studies that reported sex there were 208 men (55%) and 173 women (45%). Of the studies that reported age the mean was 53.5 years (range = 20-76 years).

Anxiety was measured using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and the Stress symptom ratings (SSR). STAI is a widely used tool to measure subject anxiety in two dimensions; State and Trait anxiety. State anxiety is a transitory emotional condition usually as a response to external stimuli, and Trait anxiety is the subject’s baseline emotional status. STAI scoring scales consists of 20 statements to which subjects respond as to how they generally feel (Trait) and how they feel currently (State). Scores range from 1-4 for each statement[23,24]. In our meta-analysis the STAI was used by 2 studies. SSR anxiety scoring includes 12 visual analogue scale ratings based on mood-related adjectives and grouped into 6 sub-scales (arousal, stress, anxiety, anger, fatigue, attention). In our meta-analysis the SSR was used by one study[6].

Patient discomfort was measured using either a numeric rating scale or a visual analog scale, which was quantified using a standardized scale[25,26].

The methodological quality and risk of bias in the trials included is shown in Figure 2.

Three studies reported on anxiety during or after flexible sigmoidoscopy[5,6,15]. Two studies used the STAI[5,15] score and 1 study used the SSR score[6].

In the studies that used STAI scores, there was no significant difference between the baseline pre- procedure STAI scores: Chlan et al[15] , the mean scores were 40.2 ± 11.9 and 36.9 ± 12.5 in the control and music arms, with a P = 0.28; in Palakanis et al[5], the respective scores were 35.68 and 36.92, with no statistically significant difference.

However, both studies showed post-procedure STAI were statistically different and that patients who listened to music had better scores compared to the control group: In Chlan et al[15], the scores were 41.8 ± 13.5 and 34.5 ± 10, with a P = 0.002; in Palakanis et al[5], the scores were 31.48 and 25.24, with a P < 0.002.

In the study by Lembo et al[6], that used SSR scoring system to measure the anxiety, the scores were 4.4 ± 0.6 and 2.8 ± 0.4 in the control and music groups respectively (P < 0.05).

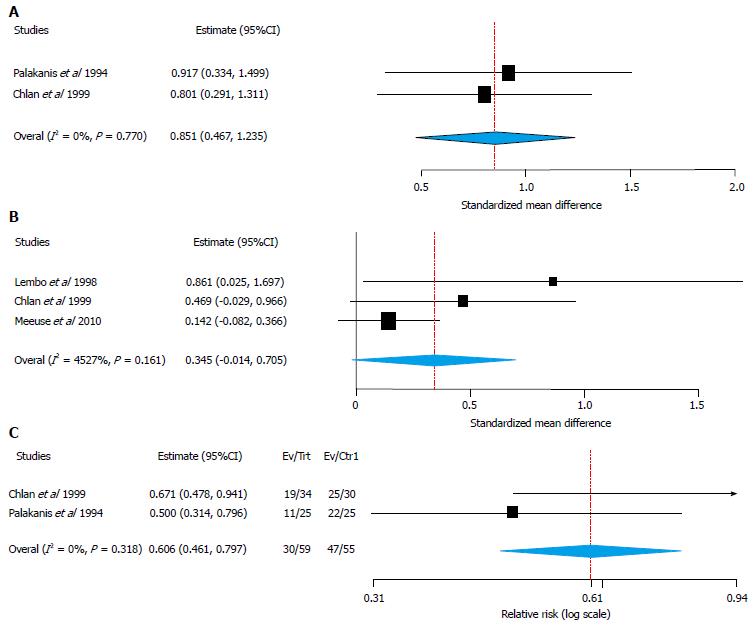

Two studies[5,15] contributed to a summative quantitative outcome and used the STAI anxiety scores. Patients who listened to music during their flexible sigmoidoscopy had less anxiety compared to those who did not [Random effects; SMD: 0.851 (0.467, 1.235), S.E = 0.196, P < 0.001] (Figure 3A). Statistical heterogeneity between studies was not significant (Q = 0.085, df = 1, P = 0.77, I2 = 0).

Three studies reported on pain during or after the flexible sigmoidoscopy[6,15,22]. In study by Chlan et al[15], there was a statistically significant difference between the control and music arms (P = 0.026). Subjects in the control group reported mean discomfort ratings of 5.2 ± 1.7, while those in the music group, reported lower discomfort ratings of 4.3 ± 2.1.

In the study by Lembo et al[6], the subjects in the music group reported a lower discomfort score of 9.5 ± 1.3, when compared to the score in the control group of 10.8 ± 1.6.

In the study by Meeuse et al[22], there was no statistically significant difference between the mean pain intensity scores in the control and intervention groups 40 ± 29 and 36 ± 27, P = 0.27).

Three studies[6,15,22] contributed to a summative quantitative outcome. Patients who listened to music during their flexible sigmoidoscopy had lower mean pain scores than those who did not, however this reduction did not reach statistical significance in the random effects model. [Random effects; SMD: 0.345 (-0.014, 0.705), S.E = 0.183, P = 0.06] (Figure 3B). Statistical heterogeneity between studies was not significant (Q = 3.65, df = 2, P = 0.161, I2 = 45).

Two studies reported on whether music was helpful during a flexible sigmoidoscopy[15]. In the study by Chlan et al[15], 25 of the 30 patients (83%) found the intervention helpful. Nineteen of the 34 (56%) subjects in the control group, did not feel music would have been helpful during the procedure.

In the study by Palakanis et al[5], 22 of 25 the subjects (88%) in the music group, deemed the intervention as helpful, while 14 of the 25 subjects (56%) felt music would not have helped or were unsure of its role.

Two studies[5,15] contributed to a summative quantitative outcome. Patients who listened to music during their flexible sigmoidoscopy found it was a useful intervention and this was statistically significant compared with patients who did not listen to music [Random effects; RR = 0.61 (0.46, 0.80), P < 0.001] (Figure 3C). Statistical heterogeneity between studies was not significant (Q = 0.999, df = 1, P = 0.318, I2 = 0).

Three[5,6,15] studies selected patients by randomization; in two of these[5,15] it was by the flip of a coin, while in the other the technique of randomization has not been described[6]. The study by Meeuse et al[22], chose control and intervention groups from consecutive patients referred for flexible sigmoidoscopy, during different periods of time. None of the studies describe concealed allocation post randomization. This does lead to an element of selection bias.

Both the subjects and the person carrying out the tests, along with the investigators collecting the data, were not blinded. This theoretically implies a high risk of performance/observer bias, but it is unavoidable considering the nature of the procedure and intervention being studied.

Publication bias was not formally assessed due to low number of studies. This may indicate there is potential for publication bias and therefore conclusions should be taken with caution. In addition, exclusion of unpublished data is a source of publication bias.

Our study has shown that music reduced anxiety during flexible sigmoidoscopy (P < 0.001). This is in keeping with other studies[27], which in a similar population to ours showed that music decreased the anxiety levels in patients undergoing awake colonoscopy, without sedation. In a study by Ovayolu et al[28], listening to Turkish classical music reduced levels of anxiety and sedative medication. This was further confirmed in a meta-analysis by Rudin et al[29]. A subsequent Randomized controlled trial by El-Hassan et al[30], demonstrated that music reduced anxiety levels in patients undergoing any type of endoscopic procedure, which was maintained across all age groups. This again is in keeping with our study findings. Music has also shown to reduce the physiological signs of stress like heart rate and blood pressure during colonoscopy, and analgesia requirements[31]. In another study by Uedo et al[32] music during colonoscopy reduced salivary cortisol levels, which was a sign of reduced stress levels.

The complex effects of music on emotions through its action on certain parts of the brain and its neurotransmitters can be an explanation for this observation. This may also explain why music reduced anxiety in women significantly when compared to men, during colonoscopy, as they were found to have a significantly higher anxiety scores before the procedure[33]. There were no reviews on effect of music on anxiety in patients undergoing flexible sigmoidoscopy alone.

Our study has also showed that patients who listened to music during flexible sigmoidoscopy deemed it more helpful compared to those who did not [Random effects; RR = 0.61 (0.46, 0.80), P < 0.001] (Figure 3C). Statistical heterogeneity between studies was not significant (Q = 0.999, df = 1, P = 0.318, I2 = 0). This is in keeping with most other studies involving music during colonoscopy, where the patients felt listening to music was helpful and improved their satisfaction scores[28,34-36].

As for the effect of music on pain and discomfort during flexible sigmoidoscopy, this is less certain. In our study, patients who listened to music had less pain and discomfort compared to those who did not listen to music, but this difference was not statistically significant [Random effects; SMD: 0.345 (-0.014, 0.705), SE = 0.183, P = 0.06] (Figure 3B). Statistical heterogeneity between studies was not significant (Q = 3.65, df = 2, P = 0.161, I2 = 45). One of the studies, by Meeuse et al[22], did not reveal any reduction in pain with music, even though the choice of music and method of intervention were not different from the other two studies. It is difficult to explain this dichotomy and lack of uniform response of pain and discomfort to music but interestingly this is replicated in similar studies involving colonoscopy[29,37]. More evidence is needed to study this variable and until then, the potential benefit of music to reduce pain should not be discounted.

The main strength of this study is the comprehensive nature of methodology and hypothesis testing. We employed traditional meta-analytical techniques to answer our hypotheses and highlight the areas that need further investigation and work. The advantage of looking into the utilization of music as an adjunct in flexible sigmoidoscopy means that there is potential for application during any medical procedure that can potentially cause distress, during which patients are awake.

The main limitation in our study pertains to the low number of studies involved in investigating the role of music specific to flexible sigmoidoscopy. Much larger, prospective, better-designed randomized controlled trials with some degree of blinding would have given much more definitive answers to this question. Even though the studies did not exhibit any statistically significant heterogeneity there was some clinical heterogeneity and results should be interpreted with caution.

Assessment of pain and its scoring were not adequately described in the studies, making interpretation difficult. Also, the techniques of patient selection, with particular attention to different subgroups like age, sex, previous surgery, previous sigmoidoscopy, could have been more thorough to make results clinically more relevant. The studies could also have described the length of the intervention, when the intervention started in relation to procedure and the type of music used and choice offered to patient, to make the methodology more comprehensive. The types of music offered to patients could have been described in detail and this may yield itself to a sub-group analysis to study the effects of different types of music.

In summary, this study has effectively documented the potential use of music as a non-pharmacological, almost cost-free intervention for allaying anxiety and potentially reducing discomfort in patients undergoing flexible sigmoidoscopy. The study also showed that music was deemed helpful intervention by patients who listened to it. In the context of relatively low uptake of screening FS, this intervention has the potential to improve patient experience and may facilitate increasing the uptake. However, we feel that further randomized studies with blinding, and involving larger sample sizes may help consolidate our findings. Sub-group analysis, with respect to age, gender, types of music, timing of intervention, duration of the intervention, previous surgery or endoscopy, baseline pain and anxiety scores, experience of the endoscopist, biopsy and therapeutic procedure during sigmoidoscopy, may help clarify further, the benefits of such relaxation and distraction techniques in improving patient experience during flexible sigmoidoscopy.

Music appears to reduce anxiety and was deemed a helpful adjunct in patients undergoing flexible sigmoidoscopy. It may also reduce pain during procedure but further studies are required to confirm this finding. This intervention may potentially improve patient experience and have a positive effect on the uptake of the screening test. There is a paucity of trials focusing only on flexible sigmoidoscopy and more work is required to consolidate our findings.

Flexible sigmoidoscopy is being increasingly used in the early detection of colorectal pathology, especially as a screening tool in asymptomatic patients. The United Kingdom Flexible Sigmoidoscopy Trial showed a once-only flexible sigmoidoscopy screening between ages 55 and 64, significantly reduced the incidence of and cancer related mortality from colorectal cancer. Despite this, the uptake of flexible sigmoidoscopy remains low, due to patients’ anxiety and concerns about discomfort and embarrassment during the procedure. So this study aims to evaluate the role of music as an adjunct during flexible sigmoidoscopy in improving patient experience.

In this study, the authors have assessed the role of music in reducing patients’ anxiety and discomfort and if this intervention was found by patients to be helpful during the test. They have reviewed comparative studies that used music as an intervention during flexible sigmoidoscopy and have performed both qualitative assessment and quantitative synthesis of outcomes. This is the first such study to systematically review and meta-analyse the use of music during flexible sigmoidoscopy in improving patient satisfaction. This is significant because unlike other endoscopic procedures like colonoscopy and oesophagogastroduodenoscopy, where intravenous sedation is widely used, flexible sigmoidoscopy is mostly performed with no sedation and hence any non-pharmacological relaxation or distraction technique will greatly improve patient experience.

This study appears to conclude that music reduced patient anxiety during the procedure and patients deemed it to be a helpful adjunct. Discomfort was also apparently improved, but a larger study may be needed to confirm this observation.

This study will encourage endoscopists to actively use music as a non-pharmacological, practically cost and risk free adjunct to improve patient experience and this may potentially help increase uptake of this very important screening test. This has helped consolidate a long-held and widely considered speculation that music can act as an effective distraction and relaxation technique during flexible sigmoidoscopy. This study was however limited by the small number of comparative studies addressing this clinical question; hence results should be interpreted with caution. However, as the intervention is completely risk and adverse effects free, this can still be applied in practice, pending further larger, better constructed randomized comparative studies.

This study deals with an innovative, well-speculated clinical question. The study has been well conducted and the paper has been clearly written and is interesting. However the number of studies analysed was small due to a relative paucity in studies involving flexible sigmoidoscopy.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Chiarioni G, Fujimori S, Meshikhes AWN, Otegbayo JN S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | World Health Organization. Cancer fact sheet N°297. Available from: http: //www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/. |

| 2. | Atkin WS, Edwards R, Kralj-Hans I, Wooldrage K, Hart AR, Northover JM, Parkin DM, Wardle J, Duffy SW, Cuzick J. Once-only flexible sigmoidoscopy screening in prevention of colorectal cancer: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375:1624-1633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1242] [Cited by in RCA: 1138] [Article Influence: 75.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | McGregor LM, Bonello B, Kerrison RS, Nickerson C, Baio G, Berkman L, Rees CJ, Atkin W, Wardle J, von Wagner C. Uptake of Bowel Scope (Flexible Sigmoidoscopy) Screening in the English National Programme: the first 14 months. J Med Screen. 2016;23:77-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tai CK, Parry H, Leicester R, Poullis A. Patient attitudes toward the implementation of flexible sigmoidoscopy bowel cancer screening (Bowelscope). Available from: http: //conference.ncri.org.uk/abstracts/2014/abstracts/B091.html. |

| 5. | Palakanis KC, DeNobile JW, Sweeney WB, Blankenship CL. Effect of music therapy on state anxiety in patients undergoing flexible sigmoidoscopy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:478-481. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Lembo T, Fitzgerald L, Matin K, Woo K, Mayer EA, Naliboff BD. Audio and visual stimulation reduces patient discomfort during screening flexible sigmoidoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1113-1116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Koelsch S. Brain correlates of music-evoked emotions. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15:170-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 536] [Cited by in RCA: 590] [Article Influence: 53.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Koelsch S. Music-evoked emotions: principles, brain correlates, and implications for therapy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2015;1337:193-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Salimpoor VN, Benovoy M, Larcher K, Dagher A, Zatorre RJ. Anatomically distinct dopamine release during anticipation and experience of peak emotion to music. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:257-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 809] [Cited by in RCA: 802] [Article Influence: 57.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zatorre RJ, Salimpoor VN. From perception to pleasure: music and its neural substrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110 Suppl 2:10430-10437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 263] [Cited by in RCA: 275] [Article Influence: 22.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Juslin PN, Barradas G, Eerola T. From Sound to Significance: Exploring the Mechanisms Underlying Emotional Reactions to Music. Am J Psychol. 2015;128:281-304. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Lee JH. The Effects of Music on Pain: A Meta-Analysis. J Music Ther. 2016;53:430-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cepeda MS, Carr DB, Lau J, Alvarez H. Music for pain relief. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;CD004843. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | White JM. Music therapy: an intervention to reduce anxiety in the myocardial infarction patient. Clin Nurse Spec. 1992;6:58-63. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Chlan L, Evans D, Greenleaf M, Walker J. Effects of a single music therapy intervention on anxiety, discomfort, satisfaction, and compliance with screening guidelines in outpatients undergoing flexible sigmoidoscopy. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2000;23:148-156. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Shanmuganandan AP, Farkas N, Siddiqui MRS, Thomas R, Mohamed S, Swift RI, Abulafi AM. The role of music in flexible sigmoidoscopy (PROSPERO 2016: CRD42016043893). Available from: http//www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp/ CRD42016043893. |

| 17. | Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13930] [Cited by in RCA: 13355] [Article Influence: 834.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wallace Byron C, Dahabreh IJ, Trikalinos TA, Lau J, Trow P, Schmid CH. “Closing the Gap between Methodologists and End-Users: R as a Computational Back-End.”. J Statistical Software. 2012;49:1-15. |

| 19. | Egger M, Smith GD, Altman DG. Systematic reviews in healthcare. London: BMJ Publishing 2006; . |

| 20. | Deeks JJ, Altman DG, Bradburn MJ. Statistical methods for examining heterogeneity and combining results from several studies in meta-analysis. Systematic reviews in health care: meta-analysis in context. London: BMJ Publication group 2001; . |

| 21. | Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration 2014; . |

| 22. | Meeuse JJ, Koornstra JJ, Reyners AK. Listening to music does not reduce pain during sigmoidoscopy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:942-945. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Spielberger CD. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press 1989; . |

| 24. | Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press 1983; . |

| 25. | Gracely RH, Dubner R. Reliability and validity of verbal descriptor scales of painfulness. Pain. 1987;29:175-185. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Heft MW, Gracely RH, Dubner R, McGrath PA. A validation model for verbal description scaling of human clinical pain. Pain. 1980;9:363-373. [PubMed] |

| 27. | López-Cepero Andrada JM, Amaya Vidal A, Castro Aguilar-Tablada T, García Reina I, Silva L, Ruiz Guinaldo A, Larrauri De la Rosa J, Herrero Cibaja I, Ferré Alamo A, Benítez Roldán A. Anxiety during the performance of colonoscopies: modification using music therapy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:1381-1386. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Ovayolu N, Ucan O, Pehlivan S, Pehlivan Y, Buyukhatipoglu H, Savas MC, Gulsen MT. Listening to Turkish classical music decreases patients’ anxiety, pain, dissatisfaction and the dose of sedative and analgesic drugs during colonoscopy: a prospective randomized controlled trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:7532-7536. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Rudin D, Kiss A, Wetz RV, Sottile VM. Music in the endoscopy suite: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Endoscopy. 2007;39:507-510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | El-Hassan H, McKeown K, Muller AF. Clinical trial: music reduces anxiety levels in patients attending for endoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:718-724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Smolen D, Topp R, Singer L. The effect of self-selected music during colonoscopy on anxiety, heart rate, and blood pressure. Appl Nurs Res. 2002;15:126-136. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Uedo N, Ishikawa H, Morimoto K, Ishihara R, Narahara H, Akedo I, Ioka T, Kaji I, Fukuda S. Reduction in salivary cortisol level by music therapy during colonoscopic examination. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:451-453. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Björkman I, Karlsson F, Lundberg A, Frisman GH. Gender differences when using sedative music during colonoscopy. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2013;36:14-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Bechtold ML, Perez RA, Puli SR, Marshall JB. Effect of music on patients undergoing outpatient colonoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:7309-7312. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Bampton P, Draper B. Effect of relaxation music on patient tolerance of gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;25:343-345. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Costa A, Montalbano LM, Orlando A, Ingoglia C, Linea C, Giunta M, Mancuso A, Mocciaro F, Bellingardo R, Tinè F. Music for colonoscopy: A single-blind randomized controlled trial. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42:871-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Bechtold ML, Puli SR, Othman MO, Bartalos CR, Marshall JB, Roy PK. Effect of music on patients undergoing colonoscopy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:19-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |