Published online May 16, 2017. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v9.i5.211

Peer-review started: November 27, 2016

First decision: January 16, 2017

Revised: February 19, 2017

Accepted: March 12, 2017

Article in press: March 13, 2017

Published online: May 16, 2017

Processing time: 172 Days and 18 Hours

To compare our developed nerve preserving technique with the non-nerve preserving one in terms of de novo bowel symptoms.

Patients affected by symptomatic apical prolapse, admitted to our department and treated by nerve preserving laparoscopic sacropexy (LSP) between October, 2010 and April, 2013 (Group A or “interventional group”) were compared to those treated with the standard LSP, between September, 2007 and December, 2009 (Group B or “control group”). Functional and anatomical data were recorded prospectively at the first clinical review, at 1, 6 mo, and every postsurgical year. Questionnaires were filled in by the patients at each follow-up clinical evaluation.

Forty-three women were enrolled, 25/43 were treated by our nerve preserving technique and 18/43 by the standard one. The data from the interventional group were collected at a similar follow-up (> 18 mo) as those collected for the control group. No cases of de novo bowel dysfunction were observed in group A against 4 cases in group B (P = 0.02). Obstructed defecation syndrome (ODS) was highlighted by an increase in specific questionnaires scores and documented by the anorectal manometry. There were no cases of de novo constipation in the two groups. No major intraoperative complications were reported for our technique and it took no longer than the standard procedure. Apical recurrence and late complications were comparable in the two groups.

Our nerve preserving technique seems superior in terms of prevention of de novo bowel dysfunction compared to the standard one and had no major intraoperative complications.

Core tip: Laparoscopic sacropexy is associated with postoperative bowel dysfunction (constipation, obstructed defecation syndrome) in 10%-50% of cases, with significant worsening in the quality of life. Iatrogenic denervation of the autonomic pelvic nerves was reported as a relevant cause of this kind of dysfunction. The aim of this observational study was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of our nerve preserving technique.

- Citation: Cosma S, Petruzzelli P, Danese S, Benedetto C. Nerve preserving vs standard laparoscopic sacropexy: Postoperative bowel function. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2017; 9(5): 211-219

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v9/i5/211.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v9.i5.211

Abdominal sacropexy was first described in 1957[1] and the first formal abdominal technique was defined by Lane[2] in 1962. A study reported the first laparoscopic sacropexy (LSP) in 1993[3], which led to its adoption and further development by different schools[4-6]. Since then various adaptations have been described in literature with different indications, techniques, meshes and associated procedures. It has been reported that the laparoscopic approach is as effective as the abdominal approach[7], with the advantages of less blood loss, a shorter hospitalization and a more rapid post-surgical recovery.

Although sacropexy does remain the “gold standard” procedure for apical prolapse[8], the subjective outcome of the procedure has been reported to be not so satisfactory as its anatomic outcome[9]. Literature has reported a 10% to 50% new onset of bowel symptoms after abdominal and laparoscopic surgery, 18% of voiding problems and 8% of women with sexual dysfunctions[10].

Although there is abundant literature of the underlying causes of urinary dysfunctions and the procedures that might be adopted to avoid them[11], there is little on the underlying causes of bowel dysfunctions.

Our recently published anatomoclinical data revealed a correlation between the occurrence of iatrogenic denervation during LSP and the postoperative onset of the obstructed defecation syndrome (ODS), identifying the source of this kind of post-LPS bowel dysfunction in the superior hypogastric plexus (SHP) iatrogenic lesion, during sacral dissection[12]. Consequently, we adopted the use of a modified dissection technique with the aim of preserving nervous pelvic autonomic pathways.

The main aim of this study was to compare the outcomes of our nerve preserving technique to those of the standard one in terms of incidence of de novo ODS and constipation. The secondary endpoints were to compare the other functional outcomes, the anatomical results and complications.

A retrospective study was carried out on patients affected by symptomatic apical prolapse, admitted to the Department of Surgical Sciences of the University of Torino between October 2010 to April 2013 and treated with nerve preserving LSP (Group A or “interventional group”). The postoperative ODS and complications of these patients were compared to those of the patients treated by the standard LSP (Group B or “control group”) between September 2007 and December 2009, the study population of our preliminary anatomoclinical research[12].

All women who presented with genital apical prolapse (vaginal or utero-vaginal), stages ≥ 2, according to the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) System[13], with clinical indication for LSP, were eligible. Patients were excluded if they were not candidates for general anaesthesia, had a history of sacropexy and/or previous rectal prolapse surgery or presacral surgery.

The data on patient age, parity, body mass index, previous abdominopelvic surgery, operating time, amount of blood loss, length of hospital stay, intraoperative, early and late postoperative complications were prospectively recorded in a computerized database. Subjective data on bladder, bowel, sexual functions and POP-Q examination were recorded prospectively at the first clinical review, then at 1 and 6 mo, followed by every postsurgical year. Questionnaires were filled in by the patients at baseline, 6 mo and then at the end of each follow-up clinical evaluation. An Italian translation of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory Short Form 20 (PFDI-20)[14], the Agachan-Wexner constipation scoring system[15] and the Prolapse/Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire Short Form (PISQ-12)[16], were used. Each patient had preoperative urodynamic tests; if stress urinary incontinence (SUI) was present, transobturator tension-free vaginal tape procedure (TVT) (Gynecare TVT-O, Ethicon Inc., Somerville, NJ) was used. The symptomatic postoperative findings, early and late complications of our two groups were then compared. Constipation was defined as ≤ 2 defecations/week for at least 3 mo; ODS was evidenced by the association of the following symptoms: Difficulty in evacuation, excessive straining during defecation, a sensation of incomplete evacuation, prolonged time to defecate and anal pain[17] and evidenced by an increase in the Agachan-Wexner score and the PFDI-20 (CRADI-8) score in answer to the questions: “Do you feel you need to strain too hard to have a bowel movement?”; “Do you usually have pain when you pass your stools?”; “Do you feel you have not completely emptied your bowel at the end of a bowel movement?”.

To avoid bias we collected the data from the interventional group at a similar follow-up as those collected in the previous review for the control group. The application of the experimental procedure was approved by the local Institutional Review Board and written informed consent was obtained from all patients before surgery.

All surgical procedures were performed by two senior gynaecologists. One 10-mm umbilical trocar, two 5-mm ancillary lateral ports and a 10-mm suprapubic ancillary trocar were used. The sigmoid colon was temporarily fixed to the abdominal wall with straight needles to improve the exposure of the promontorium and the right lumbosacral spine. A standard laparoscopic approach was used in group B patients[4,18]. Whilst group A patients were treated by our nerve preserving technique, which preserved the SHP, right hypogastric nerve (rHN), lumbosacral sympathetic trunk and inferior hypogastric plexus.

This technique can be summarized in two steps.

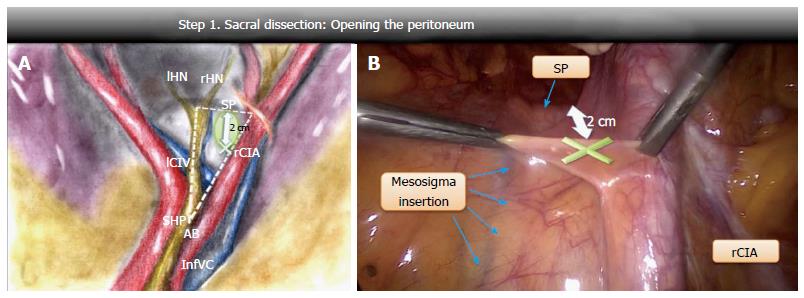

Opening of the peritoneum: Four anatomical landmarks were considered on the right lumbosacral spine: The aortic bifurcation, the mesosigma insertion on the sacral promontory, the sacral promontory and the right common iliac artery. An imaginary outline of a right-angled triangle, that we called “the dissection triangle”, was drawn by the intersection of three straight lines: One lying along the aortic axis from the aortic bifurcation to the sacral promontory (longer cathetus), the other along the sacral promontory from the mesosigma insertion to the right common iliac artery (shorter cathetus) and the last one along the right common iliac artery (hypotenuse) (Figure 1A). After being raised, the peritoneum was opened medially to the right common iliac artery about 20 mm above the sacral promontory, a safe area far from the nervous and vascular structures (Figure 1B). Infact, the SHP and the rHN run close to the major cathetus of the dissection triangle, the left common iliac vein along its 30 degree angle, the iliac bifurcation along its 60 degree angle and the middle sacral vein crosses longitudinally the central area of the triangle[12] (Figure 1A).

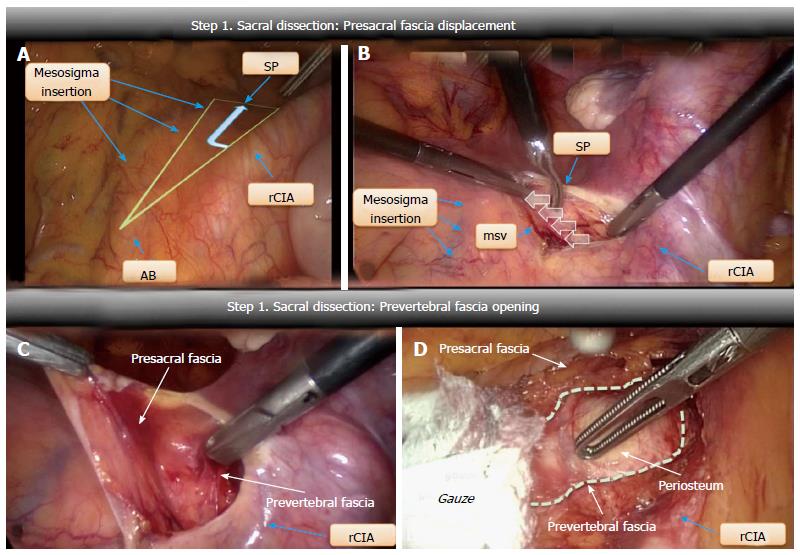

Presacral fascia medialization: The peritoneal incision was extended towards the promontory (Figure 2A). The underlying presacral fascia, containing the SHP and the rHN, was incised and pushed medially to expose the longitudinal anterior vertebral ligament. No further medial dissection was attempted once the middle sacral vein had been detected (Figure 2B).

Prevertebral fascia opening: After a small longitudinal incision, the prevertebral fascia was opened and medially pushed with a gauze until the periosteum between the lower side of L5 and the cranial portion of L5-S1 discs was visible (Figure 2C and D). The cranial aspect of the mesh was secured by tacks at this level.

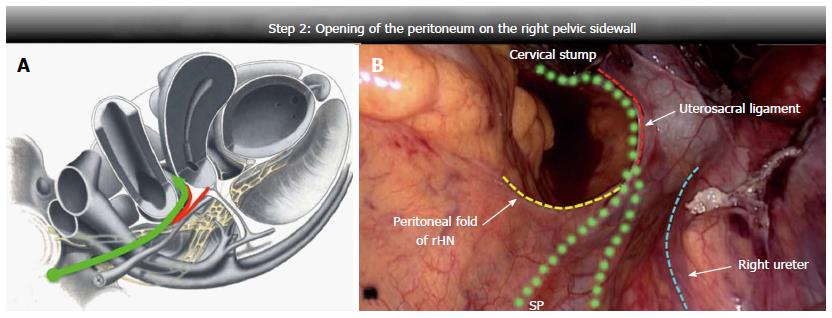

The peritoneum was opened up along the right pelvic wall; the dissection line started half way between the rHN and the ureter, then, with a lateral-medial course towards the uterosacral ligament insertion, it crossed the upper edge of the ligament at its proximal third. At this level, blunt, careful and superficial dissection was used to avoid iatrogenic damage of the rHN or pelvic plexus, close to the dissection line. The peritoneum was then opened up to the cervix or vaginal stump (Figure 3).

The procedure was then continued in the same manner for both groups, according to the steps recommended by the main schools[4,18] with adaptations. Our technique provided a recto and vesicovaginal dissection limited to the upper third of the vagina and subsequent fixation of two polypropylene rectangular mesh pieces to the anterior and posterior vaginal walls, using 3 interrupted stitches. Peritonization of the mesh through a continuous suture then followed.

Fisher’s exact test was used to determine any statistically significant differences in the distribution of outcomes in the nerve preserving LSP and non-nerve preserving LSP groups. Any two-sided P-values below 5% of the conventional threshold were considered to be statistically significant. Elaborations were made using SPSS 17.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States).

A total of 43 women were evaluable for analysis and no patient required laparotomic conversion. The standard technique was used in 18 consecutive patients and our nerve sparing technique in 25. No statistically significant differences were observed in the stage of the prolapse, or associated procedures, or personal characteristics, in the two groups under study (Table 1).

| No. of patients | Group A 25 | Group B 18 | P |

| Demographic and personal details, mean (SD) | |||

| Mean age | 55.8 (± 10.2) | 56.1 (± 8.6) | 0.9 |

| Parity | 2 (± 0.9) | 1.5 (± 0.6) | 0.14 |

| BMI | 25.2 (± 4.7) | 23.9 (± 2.7) | 0.41 |

| Symptomatic preoperative findings | |||

| Vaginal bulge, n (%) | 25 (100) | 18 (100) | > 0.99 |

| Stress urinary incontinence, n (%) | 4 (16) | 2 (11.1) | > 0.99 |

| ODS, n (%) | 0 | 0 | > 0.99 |

| Constipation, n (%) | 3 (12) | 3 (16.6) | 0.68 |

| POPDI-6 (PFDI)a, mean (SD) | 53.9 (± 13.8) | 51.6 (± 1.5) | 0.52 |

| UDI-6 (PFDI)b, mean (SD) | 12.3 (± 19.4) | 21.2 (± 2.4) | 0.21 |

| CRADI-8 (PFDI)c, mean (SD) | 9.0 (± 12.2) | 11.1 (± 1.2) | 0.58 |

| Agachan-Wexner scored, mean (SD) | 3.9 (± 4.2) | 6.4 (± 9.1) | 0.08 |

| PISQ-12e, mean (SD) | 10.1 (± 3.9) | 9.11 (± 3.8) | 0.38 |

| POP-Q stage at baseline, n (%) | |||

| Utero-vaginal prolapse | 13 (52) | 14 (77.8) | 0.11 |

| Vaginal cuff prolapse | 6 (24) | 4 (28.6) | > 0.99 |

| Anterior stage 2 | 12 (48) | 8 (44.4) | > 0.99 |

| Anterior stage 3 | 5 (20) | 7 (38.8) | 0.3 |

| Anterior stage 4 | 0 | 0 | > 0.99 |

| Apical stage 2 | 12 (48) | 7 (38.8) | 0.75 |

| Apical stage 3 | 10 (40) | 9 (50) | 0.54 |

| Apical stage 4 | 3 (12) | 2 (11.1) | > 0.99 |

| Posterior stage 2 | 3 (12) | 5 (27.7) | 0.24 |

| Posterior stage 3 | 2 (8) | 0 | 0.5 |

| Posterior stage 4 | 0 | 0 | > 0.99 |

| Intraoperative data | |||

| Concomitant subtotal hysterectomy, n (%) | 13 (52) | 13 (72.2) | 0.21 |

| Concomitant total hysterectomy, n (%) | 0 | 1 (5.5) | 0.41 |

| Concomitant sub-urethral sling placement, n (%) | 4 (16) | 2 (11.1) | > 0.99 |

| Cervical stump fixation, n (%) | 13 (52) | 13 (72.2) | 0.21 |

| Vaginal cuff fixation, n (%) | 6 (24) | 5 (27.8) | > 0.99 |

| Uterine preservation, n (%) | 6 (24) | 0 | 0.03 |

| Operating time (min), mean (SD) | 132 (± 27) | 141 (± 21) | 0.11 |

| Hb decrease (g/dL), mean (SD) | 1.1 (± 0.6) | 1.2 (± 0.5) | 0.48 |

| Hospital stay, mean (SD) | 2.2 (± 1.1) | 2.9 (± 1.1) | 0.06 |

The group B follow-up followed the same time frame as the one we had previous used in the anatomoclinical study[12]. So as to make the two groups as comparable as possible, we analyzed group A at similar follow-up times as those used for group B, as this time was considered adequate enough to evidence any early post-surgical dysfunctional complications, which were the object of our study. No significant differences were observed in either group at similar follow-ups as to the symptomatic postoperative findings, anatomical outcome, late complications, prolapse and urinary related quality of life. Bowel function and related quality of life was the exception, as there were no cases of ODS in the nerve sparing LSP group, against 4 cases (4/18; 22%) in the standard LSP group (P = 0.02), equally distributed between the two surgeons (Table 2).

| No. of patients | Group A 25 | Group B 18 | P |

| Follow-up, mo (SD) | 19.5 (± 8.4) | 17.3 (± 9.8) | 0.33 |

| Symptomatic post-operative findings | |||

| Persistent vaginal bulge, n (%) | 2 (8) | 1 (5.5) | > 0.99 |

| De novo stress urinary incontinence, n (%) | 0 | 3 (16.6) | 0.07 |

| De novo ODS, n (%) | 0 | 4 (22.2) | 0.021 |

| De novo constipation, n (%) | 0 | 0 | > 0.99 |

| POPDI-6 (PFDI)a, mean (SD) | 4 (± 11.6) | 6.8 (± 1.5) | 0.5 |

| UDI-6 (PFDI)b, mean (SD) | 3.2 (± 5.4) | 7.1 (± 1.0) | 0.11 |

| CRADI-8 (PFDI)c, mean (SD) | 8.3 (± 12.2) | 16.9 (± 21.6) | 0.1 |

| Agachan-Wexner scored, mean (SD) | 3.0 (± 3.0) | 6.8 (± 5.2) | 0.00 |

| PISQ-12e, mean (SD) | 7.6 (3.3) | 5.7 (± 2.9) | 0.06 |

| Anatomical results, n (%) | |||

| Recurrence of vault prolapse | 0 | 1 (5.5) | 0.41 |

| Cystocele recurrence/de novo | 1 (4) | 1 (5.5) | > 0.99 |

| Rectocele recurrence/de novo | 0 | 0 | > 0.99 |

| Late complications, n (%) | |||

| Erosion | 0 | 1 (5.5) | 0.41 |

| Reinterventionf | 1 (4) | 2 (11.1) | 0.56 |

The quality of life of the patients who were suffering from post LSP ODS worsened as they could not evacuate spontaneously, meaning the use of daily microenemas for at least 3 post-surgical months. Bowel dysfunction was clinically characterized by difficult, incomplete and painful defecation as evidenced by an increase in the quality of life and symptomatic questionnaire scores. Anorectal manometry evidenced that patients with bowel dysfunction had an objective basal spasticity of the anal sphincter with poor relaxation under strain, along with a slightly endorectal sensitivity reduced. There was a gradual improvement of ODS over time and, although it did not disappear altogether, the average CRADI-8 and Agachan-Wexner scores were lower at 2 years (47.5 → 14 and 13.2 → 7, respectively). Indeed, only 2/4 patients had values comparable to those of controls at the two-year follow-up. Although there were no cases of de novo constipation in any of the patients, all those present preoperatively persisted.

One patient in both groups required reoperation for anterior mesh detachment, whereas 1 patient in Group B had second surgery for mesh erosion, without any total reoperation rate difference. No interventional procedure was switched to the classical one.

Bowel dysfunction after LSP has been poorly investigated and when it has been reported it has been defined in different ways, such as constipation, ODS and dyschezia. Moreover, it has often been evaluated with the use of non-validated questionnaires, without preoperative data and sometimes even in the presence of concomitant confounding procedures. We reviewed the current literature on LSP, pooling studies that accurately reported functional outcomes, procedural steps, associated procedures, mesh types and placement, in order to accurately quantify this issue (Table 3).

| Ref. | N° pz | FU (mo) | Bowel dysfunction (n) | Bowel dysfunction (%) | SUI (n) | SUI (%) | Associated procedures | Mesh characteristics | |||||||||||

| SLH | TLH | Uterus pres. | TOT/TVT | Burch | PVR | ACR | PCR | LM | Type | N° | Anterior placement | Posterior placement | |||||||

| [5] | 77 | 11.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 60 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 74 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 55 | Polyest. | 2 | Vagina | Vagina |

| [19] | 41 | 24 | 1 (ODS) | 2.4 | 1 | 2.4 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Polyest. | 2 | Below the trigone | Perineal body | |

| [20] | 71 | 27.5 | 48 (C) | 65.7 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 55 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Polyest. | 1 or 2 | Vagina | Levator ani | |

| [21] | 325 | 14.6 | 20 (C) | 6 | 19 | 5.8 | 0 | 15 | 163 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Polyest. | 2 | Vagina | Levator ani | |

| [18] | 43 | 60 | 2 (ODS) | 4.6 | 1 | 2.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 46 | 28 | 0 | 19 | 0 | Polyprop. | 2 | Vagina | Perineal body/vagina | |

| [22] | 101 | 12 | 18 (C) | 17.8 | 24 | 23.7 | 55 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Polyprop. | 2 | Below the trigone | Levator ani | |

| [23] | 83 | 21 | 19 (C) | 22.8 | 4 | 4.8 | 12 | 29 | 38 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Polyprop. | 2 | Vagina | Levator ani | |

| [24] | 138 | 43 | 26 (C;ODS) | 13.4 (C) 5.8 (ODS) | 7 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 63 | 63 | 24 | 77 | 0 | Polyest. | 2 | Vagina | Levator ani/vagina | |

| [25] | 47 | 33.5 | 8 (C) | 17 | 6 | 12.7 | / | 0 | / | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Xenograft | 2 | Vagina | Levator ani | |

| [26] | 132 | 12.5 | 5 (C) | 3.7 | 8 | 6 | 12 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Polyprop. | 2 | Vagina | Levator ani | |

| [27] | 84 | 30.7 | 23 (C;ODS) | 15.4 (C) 11.9 (ODS) | 18 | 21.4 | 9 | 83 | 9 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Polyest. | 2 | Vagina | Levator ani |

| [28] | 176 | 60 | 47 (C) | 26.3 | 7 | 3.9 | 0 | 13 | 100 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | polyprop. | 2 | Vagina (before the trigone) | Levator ani | |

| [29] | 116 | 34 | 2 (C;D) | 1.7 (C) 0 (D) | 6 | 5.1 | 56 | 0 | 28 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Polyest. | 2 | Vagina | Levator ani | |

| [30] | 501 | 20.7 | 28 (C) | 5.5 | 18 | 3.5 | nr | nr | nr | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Polyest./ polyprop. | 2 | Vagina (before the trigone) | Levator ani | |

| [31] | 80 | 12 | 13 (ODS) | 16.2 | 10 | 12.5 | 47 | 0 | 37 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Polyest. | 2 | Vagina (3°superior) | Levator ani | |

| [32] | 150 | 2 | 8 (C;ODS) | 3.3 (C) 2 (ODS) | 10 | 6.6 | 26 | 0 | 35 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Polyest./ polyprop. | 1 or 2 | nr | Levator ani | |

| 2165 (total) | 26.5 (mean) | 268 (total) | 12.3 (mean) | 139 (total) | 6.4 (mean) | ||||||||||||||

Although SUI de novo was invariably reported to have similar rates in all studies, the rate of bowel dysfunction varied greatly (SUI range: 0%-23.7%/ODS range: 0%-65.7%). This surprising variability cannot be explained by the associated procedures alone. In fact, though the post LSP bowel dysfunction rate correlates with the positioning of the single posterior mesh[33] and rises after deep posterior dissection, this variability is also found in homogeneous studies with the same associated procedures, e.g., levator ani mesh anchorage (Table 3).

On the other hand, although studies without confounding associated procedures, like our case series, have a lower incidence of dysfunction, it does not reach zero[5]. This might indicate that other pathologic conditions influence bowel functions and that this complication, unlike urinary dysfunction, cannot be attributed solely to the anatomic postoperative aspects. Therefore, the hypothesis of iatrogenic denervation might well provide an explanation for this variability and justify the postoperative bowel dysfunction rate, which would otherwise be unexplainable.

Group B was the same target population as our previous anatomoclinical study[12], where a correlation between an iatrogenic nerve lesion during dissection of the sacral promontory and bowel postoperative dysfunction was demonstrated, with the identification of the involved nerves in the caudal part of the SHP. An objective gynecological and proctological clinical evaluation excluded any secondary functional and organic underlying causes of ODS. As our technique involves anchorage to the upper third of the vaginal stump, post LSP bowel dysfunction could not be attributed to the depth of posterior mesh placement in our series. Furthermore, bowel dysfunction was found both after sacrocervicopexy (3 patients) and sacrocolpopexy (1 patient) without any significant difference.

To date, the rates of iatrogenic pelvic nerve damage after surgery for pelvic prolapse have not yet been quantified, therefore, it is most likely that they have been widely underestimated. Possover analyzed 93 patients who had referred to his centre complaining of symptoms related to probable pelvic nerve damage secondary to surgery for pelvic prolapse[34]. The most frequently observed injury was damage to the sacral nerve roots secondary to laparoscopic rectopexy. He used the term “primary nerve injuries” to describe any nerve lesions caused by coagulation, suturing, ischemia or cutting. Whilst the term “secondary nerve entrapments” was used for lesions caused by fibrotic tissue or vascular compression. Nerve injury after LSP may be associated with both kinds of nerve damage. The ODS observed in Group B onset soon after surgery and gradually improved over time, even if it did persist in 2/4 patients. Early onset is typical of a primary nerve injury, whilst the presence of a temporary functional deficit, that partially resolves in variable time lapses, is a common finding in partial nerve damage. The basal internal anal sphincter tone is under the modulation of the sympathetic autonomic system[35]. Conversely, the parasympathetic nervous system is responsible for internal anal sphincter relaxation[36]. Mechanoreceptors transmit signals via the SHP promoting sphincter constriction until distention signaling overcomes the sympathetic tonic firing and defecation occurs. Extrinsic compression or lesions to only a few nerve fibres most commonly induces irritative symptoms that are connected to either a hypersensitivity or hyperactivity of the pelvic visceral organs, which accounts for the anal sphincter hypertonia we observed.

Some kind of underlying neurological cause for the bowel complications observed after LSP has been invoked, but without further elaboration. However, Shiozawa et al[37]’s 2010 study was in agreement with ours and suggested that dysfunctional consequences post laparotomic sacropexy were due to lesions of the autonomic fibers, advocating their preservation. In their recently published overview on surgery involving the presacral space, Huber et al[38] included sacropexy amongst the procedures at risk of postoperative bladder and bowel dysfunctions due to iatrogenic nerve injury.

Three de novo SUI were observed in Group B and 2/3 of these patients had ODS and negative pre-surgical urodynamic testing. Undoubtedly, the preservation of autonomic fibres is able to prevent the onset of urinary dysfunctions[39]. However, on the basis of the data obtained in our study, we cannot definitely conclude that there are no other underlying causes of the SUI observed in the ODS patients. Likewise, the data obtained from our review did not show a linear relationship between the urinary and bowel dysfunction (Pearl index -0.04) (Table 3). Furthermore, the dysfunctional patients reported a slight worsening in their sexuality, even if this was not statistically significant.

We are well aware that this study does have limitations, i.e., its retrospective design and the relatively small sample size. However, the comparable follow-up period and population sample, the absence of concomitant surgical procedures and the administration of validated questionnaires, allowed us to mitigate confounders and make an adequate assessment of the dysfunctional symptoms.

The nerve preserving technique we developed has shown to be both effective and safe. Moreover, it took no longer than did the standard technique to perform and there were no major intraoperative complications. The curve of nerve preserving procedure time demonstrated no specific learning effect.

Furthermore, we are of the opinion that our technique should be studied in a systematic fashion and cannot be generalized due to the heterogeneity in the suspension techniques and anchoring sites used by other authors. However, our personal experience and the data we have obtained, lead us to conclude that a midline, medial dissection, over the sacral promontory, close to the mesosigma insertion, is to be avoided and that the location of neural pathways must be borne in mind throughout the steps involved in this urogynecological procedure.

The authors would like to thank Barbara Wade for her linguistic advice.

The authors recently carried out an anatomoclinical study on the laparoscopic sacropexy (LSP) which demonstrated the correlation between the iatrogenic lesion of the autonomic nerves during sacral promontory dissection and postoperative obstructed defecation syndrome (ODS), identifying the fibers involved in the caudal part of the superior hypogastric plexus (SHP). The aim of this current observational study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a modified sacral dissection technique that the authors later adopted and called “nerve preserving”.

Results from this study may encourage surgeons to develop and systematically adopt pelvic nerve sparing techniques also for other kinds of benign reconstructive surgery with the aim of improving the patients’ quality of life. Although nerve preserving technique does seem to be effective, the interesting data the authors obtained, require further confirmatory study and research.

Patient quality of life is the goal of every surgical procedure which approaches a benign pathology. However there is a risk of invalidating the good results due to the iatrogenic morbidity that follows many surgical procedures. The nervous origin of the bowel complications after LSP has sometimes been invoked, but without any further elaboration. “Borrowing” a concept from oncological surgery, the authors developed and applied a nerve sparing technique in this benign pathology. To the best of our knowledge, to date, there are no published data on the clinical outcomes of a nerve preserving technique in a benign gynaecological procedure.

The research attempted to reduce the relevant iatrogenic morbidity of a procedure considered the “anatomical gold standard” in the correction of the central segment prolapse. This retrospective study supports the hypothesis that a nerve preserving technique produces better clinical outcomes. The results from future randomized controlled trials could well provide a higher level of evidence as to the potential benefits of this procedure.

In this study, “nerve preserving” technique during LSP referred to a surgical procedure that aims at sparing the autonomic component of the female pelvis, specifically the orthosympathetic fibers of the SHP and the right hypogastric nerve.

It is a well written manuscript concerning the outcome of nerve preserving procedure in laparoscopic sacropexy focusing on the outcome of bowel function. It is very helpful for the readers.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Hefny AF, Katsanos KH, Pan HC, Takano S S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Arthure HG, Savage D. Uterine prolapse and prolapse of the vaginal vault treated by sacral hysteropexy. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp. 1957;64:355-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lane FE. Repair of posthysterectomy vaginal-vault prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 1962;20:72-77. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Dorsey JH, Sharp HT. Laparoscopic sacral colpopexy and other procedures for prolapse. Baillieres Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;9:749-756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wattiez A, Canis M, Mage G, Pouly JL, Bruhat MA. Promontofixation for the treatment of prolapse. Urol Clin North Am. 2001;28:151-157. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Cosson M, Rajabally R, Bogaert E, Querleu D, Crépin G. Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy, hysterectomy, and burch colposuspension: feasibility and short-term complications of 77 procedures. JSLS. 2002;6:115-119. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Drent D. Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy for vaginal vault prolapse: personal experience. N Z Med J. 2001;114:505. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Freeman RM, Pantazis K, Thomson A, Frappell J, Bombieri L, Moran P, Slack M, Scott P, Waterfield M. A randomised controlled trial of abdominal versus laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy for the treatment of post-hysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse: LAS study. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:377-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Maher CF, Feiner B, DeCuyper EM, Nichlos CJ, Hickey KV, O’Rourke P. Laparoscopic sacral colpopexy versus total vaginal mesh for vaginal vault prolapse: a randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:360.e1-360.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Higgs PJ, Chua HL, Smith AR. Long term review of laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy. BJOG. 2005;112:1134-1138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nygaard IE, McCreery R, Brubaker L, Connolly A, Cundiff G, Weber AM, Zyczynski H. Abdominal sacrocolpopexy: a comprehensive review. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:805-823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 683] [Cited by in RCA: 644] [Article Influence: 30.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Brubaker L, Cundiff GW, Fine P, Nygaard I, Richter HE, Visco AG, Zyczynski H, Brown MB, Weber AM. Abdominal sacrocolpopexy with Burch colposuspension to reduce urinary stress incontinence. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1557-1566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 411] [Cited by in RCA: 366] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cosma S, Menato G, Ceccaroni M, Marchino GL, Petruzzelli P, Volpi E, Benedetto C. Laparoscopic sacropexy and obstructed defecation syndrome: an anatomoclinical study. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:1623-1630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bø K, Brubaker LP, DeLancey JO, Klarskov P, Shull BL, Smith AR. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:10-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Barber MD, Walters MD, Bump RC. Short forms of two condition-specific quality-of-life questionnaires for women with pelvic floor disorders (PFDI-20 and PFIQ-7). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:103-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 826] [Cited by in RCA: 989] [Article Influence: 49.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Agachan F, Chen T, Pfeifer J, Reissman P, Wexner SD. A constipation scoring system to simplify evaluation and management of constipated patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:681-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 818] [Cited by in RCA: 851] [Article Influence: 29.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rogers RG, Coates KW, Kammerer-Doak D, Khalsa S, Qualls C. A short form of the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire (PISQ-12). Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2003;14:164-18; discussion 168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 555] [Cited by in RCA: 574] [Article Influence: 26.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Davis K, Kumar D. Posterior pelvic floor compartment disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;19:941-958. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ross JW, Preston M. Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy for severe vaginal vault prolapse: five-year outcome. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12:221-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Gadonneix P, Ercoli A, Salet-Lizée D, Cotelle O, Bolner B, Van Den Akker M, Villet R. Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy with two separate meshes along the anterior and posterior vaginal walls for multicompartment pelvic organ prolapse. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2004;11:29-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Antiphon P, Elard S, Benyoussef A, Fofana M, Yiou R, Gettman M, Hoznek A, Vordos D, Chopin DK, Abbou CC. Laparoscopic promontory sacral colpopexy: is the posterior, recto-vaginal, mesh mandatory? Eur Urol. 2004;45:655-661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Rozet F, Mandron E, Arroyo C, Andrews H, Cathelineau X, Mombet A, Cathala N, Vallancien G. Laparoscopic sacral colpopexy approach for genito-urinary prolapse: experience with 363 cases. Eur Urol. 2005;47:230-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sarlos D, Brandner S, Kots L, Gygax N, Schaer G. Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy for uterine and post-hysterectomy prolapse: anatomical results, quality of life and perioperative outcome-a prospective study with 101 cases. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:1415-1422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Xiromeritis P, Marotta ML, Royer N, Kalogiannidis I, Degeest P, Devos F. Outcome of laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy with anterior and posterior mesh. Hippokratia. 2009;13:101-105. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Granese R, Candiani M, Perino A, Romano F, Cucinella G. Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy in the treatment of vaginal vault prolapse: 8 years experience. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;146:227-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Deprest J, De Ridder D, Roovers JP, Werbrouck E, Coremans G, Claerhout F. Medium term outcome of laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy with xenografts compared to synthetic grafts. J Urol. 2009;182:2362-2368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Claerhout F, De Ridder D, Roovers JP, Rommens H, Spelzini F, Vandenbroucke V, Coremans G, Deprest J. Medium-term anatomic and functional results of laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy beyond the learning curve. Eur Urol. 2009;55:1459-1467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Bui C, Ballester M, Chéreau E, Guillo E, Daraï E. [Functional results and quality of life of laparoscopic promontofixation in the cure of genital prolapse]. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2010;38:563-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Sabbagh R, Mandron E, Piussan J, Brychaert PE, Tu le M. Long-term anatomical and functional results of laparoscopic promontofixation for pelvic organ prolapse. BJU Int. 2010;106:861-866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sergent F, Resch B, Loisel C, Bisson V, Schaal JP, Marpeau L. Mid-term outcome of laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy with anterior and posterior polyester mesh for treatment of genito-urinary prolapse. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;156:217-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Bacle J, Papatsoris AG, Bigot P, Azzouzi AR, Brychaet PE, Piussan J, Mandron E. Laparoscopic promontofixation for pelvic organ prolapse: a 10-year single center experience in a series of 501 patients. Int J Urol. 2011;18:821-826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Perez T, Crochet P, Descargues G, Tribondeau P, Soffray F, Gadonneix P, Loundou A, Baumstarck-Barrau K. Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy for management of pelvic organ prolapse enhances quality of life at one year: a prospective observational study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18:747-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Thubert T, Naveau A, Letohic A, Villefranque V, Benifla JL, Deffieux X. Outcomes and feasibility of laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy among obese versus non-obese women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;120:49-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Leveau E, Bouchot O, Lehur PA, Meurette G, Lenormand L, Marconnet L, Rigaud J. [Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy results contingent on mesh position]. Prog Urol. 2011;21:426-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Possover M, Lemos N. Risks, symptoms, and management of pelvic nerve damage secondary to surgery for pelvic organ prolapse: a report of 95 cases. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22:1485-1490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Garrett JR, Howard ER, Jones W. The internal anal sphincter in the cat: a study of nervous mechanisms affecting tone and reflex activity. J Physiol. 1974;243:153-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Matsufuji H, Yokoyama J. Neural control of the internal anal sphincter motility. J Smooth Muscle Res. 2003;39:11-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Shiozawa T, Huebner M, Hirt B, Wallwiener D, Reisenauer C. Nerve-preserving sacrocolpopexy: anatomical study and surgical approach. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;152:103-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Huber SA, Northington GM, Karp DR. Bowel and bladder dysfunction following surgery within the presacral space: an overview of neuroanatomy, function, and dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26:941-946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Junginger T, Kneist W, Heintz A. Influence of identification and preservation of pelvic autonomic nerves in rectal cancer surgery on bladder dysfunction after total mesorectal excision. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:621-628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |