Published online Apr 16, 2017. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v9.i4.171

Peer-review started: July 25, 2016

First decision: October 20, 2016

Revised: December 16, 2016

Accepted: January 2, 2017

Article in press: January 3, 2017

Published online: April 16, 2017

Processing time: 266 Days and 18.7 Hours

To evaluate the risk of immediate and delayed bleeding following sphincterotomy procedure.

This retrospective cohort study was conducted with all patients who underwent endoscopic sphincterotomy during January 2006 to September 2015 at a tertiary academic center. Patients were grouped according to pre procedural usage of serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs). Both groups were matched for demographic and clinical characteristics. Patients with thrombocytopenia, increased international normalized ratio, or a history of bleeding or coagulation disorders, concurrent use of other antiplatelet/anticoagulants were excluded from the study.

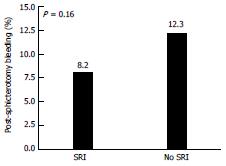

A total of 447 patients were included, of which 219 (45.9%) used SRIs and 228 (54.1%) cases did not. There was no significant difference in acute or delayed bleeding during endoscopic sphincterotomy between the two groups. (8.2% vs 12.3%, P = 0.16).

The use of SRIs was not associated with an increased risk of post-sphincterotomy bleeding. To our best knowledge, this is the first study to explore this association.

Core tip: Serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs) are a very commonly prescribed medication. The use of SRIs is reportedly associated with an increased risk for gastrointestinal bleeding in few studies. In this retrospective cohort study we analyzed the association between use of SRI and risk of post sphincterotomy bleeding with meticulous exclusion of all the confounders associated with increased risk of sphincterotomy bleeding. To our knowledge, this is a first study to assess the SRIs impact on post sphincterotomy bleeding.

- Citation: Yadav D, Vargo J, Lopez R, Chahal P. Does serotonin reuptake inhibitor therapy increase the risk of post-sphincterotomy bleeding in patients undergoing endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography? World J Gastrointest Endosc 2017; 9(4): 171-176

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v9/i4/171.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v9.i4.171

Since its earliest description in 1974, endoscopic sphincterotomy has become a commonly performed procedure for a variety of therapeutic indications during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)[1]. Including choledocholithiasis, placement of stents through malignant and benign strictures, as well as to treat dysfunction of the sphincter of Oddi. It is a technically difficult endoscopic procedure performed under visual and fluoroscopic guidance. It involves deep insertion of the cannula into the bile duct through the ampulla of Vater and the subsequent use of electrocautery to incise the sphincter of Oddi. Sphincterotomy has been associated with pancreatitis, hemorrhage, perforation and other complications most of which occur within the initial 24 h of procedure[2,3]. Hemorrhage is a well-known complication occurring in up to 2%-7% of all cases[1].

Serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs) are considered to be a first-line pharmacologic therapy for depression, and are among the most commonly prescribed medications in the United States. The safety and side effect profile of these drugs have been well-described in the existing literature. In numerous studies, SRI therapy has been associated with an increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. Similarly, the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), anticoagulants and aspirin has been associated with an increased risk of bleeding during sphincterotomy procedures[4]. These drugs are typically discontinued a week prior to the procedure date. Our aim was to evaluate the risk of immediate and delayed bleeding following sphincterotomy procedure. Our hypothesis was that SRIs medications increase the risk of post sphincterotomy bleeding.

Immediate post endoscopic sphincterotomy (post-ES) bleeding is considered to be oozing of blood during ERCP. Delayed post ES bleeding occurs within 10 d after ERCP and manifested as melena, hematemesis or hematochezia (Table 1). Classification of bleeding according to Cotton et al[3] states mild bleeding is defined as hemoglobin drop of less than 3 g/dL without the need of transfusion, moderate bleeding is considered when blood transfusion of 4 units or less is required without any surgical intervention, severe bleeding is defined as blood transfusion of 5 units or more and surgical intervention is required (Table 2).

| Complications of sphincterotomy | Risk factors for hemorrhage |

| Pancreatitis - 1.0%-15.7% (Most common complication) | Presence of coagulopathy |

| Hemorrhage - 2%-7% | Use of anti-coagulation |

| Cholangitis - 1% - (Fever, chills, elevated liver enzymes, and/or positive blood culture within 48 h after the procedure) | Cholangitis |

| Cholecystitis - (Clinical and radiographic evidence of an inflamed gallbladder) | Low endoscopist case volume |

| Mild | Moderate | Severe |

| Transfusion is not required, with evidence of bleeding | Transfusion of 4 units or less is required | Transfusion of 5 units or more is required |

| Hemoglobin drop of less than 3 g/dL | No surgical intervention | Angiographic or surgical intervention |

| Immediate bleeding - seen in 30% patients (8) - endoscopic venous oozing which stopped with epinephrine | ||

| Delayed bleeding - occur up to 2 wk after the procedure - hematemesis, melena, haematochezia | ||

| Severe bleeding - 0.1%-0.5% | ||

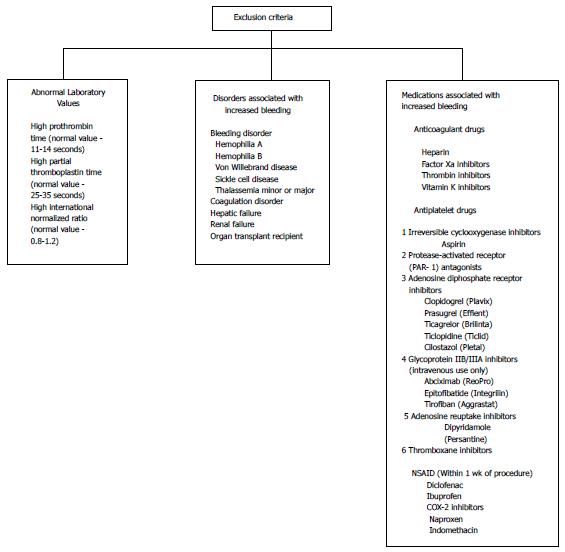

This retrospective cohort study was conducted after obtaining necessary approval from the Institution Review Board and patients consent. Patients who underwent ERCP with sphincterotomy at a tertiary referral center by a group of ten therapeutic endoscopists with a minimum of 5 years of experience during the study period of January 2006 - September 2015 were reviewed. One of the confounding factor of bleeding is low endoscopist case volume (Table 1). This study was conducted at a tertiary referral center with an average 2500 ERCP are performed in a year, in total 22500 during 2006-2015. SRI is a commonly prescribed drug in United States. Patients using either selective SRIs or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) at the time of the procedure were included (Table 3). The patients were grouped according to whether they continued to take SRIs until the day of the procedure and patients who never had been on SRI’s or SNRI’s. Patients SRI dose wasn’t included as the purpose of study was to analysis bleeding risk with SRI therapy. Patients with following risk factors that could independently increase the risk of bleeding (such as coagulopathies, liver disorders, and cholangitis), patients taking aspirin and NSAIDs, patients with abnormal lab values for PT-INR > 1.5, platelet count < 150000, and PTT > 25 s were excluded from the study (Figure 1). Data pertaining to the patient demographics (Tables 4 and 5), technical aspects of the procedure (Tables 6 and 7), medical co-morbidities including renal, cardiac, hepatic issues, coagulation disorder, bleeding disorder, history of alcohol intake, drug history, coagulation profile, platelet levels, recent antiplatelet or NSAID use was abstracted.

| Serotonin reuptake inhibitors | Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors |

| Citalopram (Celexa) | Desvenlafaxine (Pristiq) |

| Escitalopram (Lexapro, Cipralex) | Duloxetine (Cymbalta) |

| Paroxetine (Paxil, Seroxat) | Levomilnacipran (Fetzima) |

| Fluoxetine (Prozac) | Milnacipran (Ixel, savella) |

| Fluvoxamine (Luvox) | Tofenacin (Elamol, tofacine) |

| Sertraline (Zoloft, lustral) | Venlafaxine (Effexor) |

| Factor | Overall (n = 447) | SRI (n = 219) | No SRI (n = 228) | P value | |||

| n | Summary | n | Summary | n | Summary | ||

| Age (yr) | 445 | 64.4 ± 17.9 | 219 | 64.0 ± 16.8 | 226 | 64.7 ± 19.0 | 0.681 |

| Male | 447 | 112 (25.1) | 219 | 47 (21.5) | 228 | 65 (28.5) | 0.0863 |

| BMI | 442 | 29.5 ± 7.5 | 218 | 29.7 ± 7.6 | 224 | 29.3 ± 7.4 | 0.591 |

| Smoking | 435 | 216 (49.7) | 216 | 114 (52.8) | 219 | 102 (46.6) | 0.203 |

| Alcohol use | 432 | 161 (37.3) | 215 | 69 (32.1) | 217 | 92 (42.4) | 0.0273 |

| Cardiovascular disorder | 447 | 111 (24.8) | 219 | 53 (24.2) | 228 | 58 (25.4) | 0.763 |

| Depression | 445 | 160 (36.0) | 219 | 99 (45.2) | 226 | 61 (27.0) | < 0.0013 |

| Renal disease | 447 | 55 (12.3) | 219 | 30 (13.7) | 228 | 25 (11.0) | 0.383 |

| Intestinal disease | 447 | 66 (14.8) | 219 | 29 (13.2) | 228 | 37 (16.2) | 0.373 |

| History of UGI bleed | 389 | 1 (0.26) | 207 | 0 (0.0) | 182 | 1 (0.55) | 0.474 |

| Factor | Overall (n = 447) | SRI (n = 219) | No SRI (n = 228) | P value | |||

| n | Summary | n | Summary | n | Summary | ||

| PPI | 447 | 111 (24.8) | 219 | 51 (23.3) | 228 | 60 (26.3) | 0.462 |

| Platelets | 435 | 213 | 222 | 0.591 | |||

| 140-400 | 432 (99.3) | 212 (99.5) | 220 (99.1) | ||||

| > 400 | 3 (0.69) | 1 (0.47) | 2 (0.90) | ||||

| INR | 391 | 190 | 201 | - | |||

| 0.9-1.2 | 391 (100.0) | 190 (100.0) | 201 (100.0) | ||||

| PTT | 361 | 171 | 190 | - | |||

| 24.7-32.7 s | 361 (100.0) | 171 (100.0) | 190 (100.0) | ||||

| Number of ERCPs | Overall (n = 447) | SRI (n = 219 ) | No SRI (n = 228) | P value |

| 1 | 432 (96.6) | 214 (97.7) | 218 (95.6) | 0.231 |

| 2 | 13 (2.9) | 3 (1.4) | 10 (4.4) | |

| 3 | 2 (0.45) | 2 (0.91) | 0 (0.0) |

| Overall (n = 447) | SRI (n = 219) | No SRI (n = 228) | P value | ||

| Summary | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Abnormal CT | 16 (3.8) | 9 (4.3) | 7 (3.3) | 0.571 | |

| Abdominal pain | 90 (21.2) | 43 (20.6) | 47 ( 21.9) | 0.751 | |

| Abnormal LFT | 62 (14.6) | 32 (15.3) | 30 (14.0) | 0.691 | |

| Biliary dilation | 8 (1.9) | 6 (2.9) | 2 (0.93) | 0.172 | |

| Bile duct stones | 187 (44.1) | 96 (45.9) | 91 (42.3) | 0.451 | |

| Complications of prior biliary surgery | 6 (1.4) | 4 (1.9) | 2 (0.93) | 0.442 | |

| Jaundice | 49 (11.6) | 16 (7.7) | 33 (15.3) | 0.0131 | |

| Cholangitis | 9 (2.1) | 209 | 4 (1.9) | 5 (2.3) | 0.992 |

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD or median (25th, 75th percentiles) and categorical factors as frequency (percentage). A univariable analysis was performed to assess differences between subjects who used SRIs at the time of ERCP and those who did not. Analysis of variance or the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis tests were used for continuous or ordinal variables and Pearson’s χ2 tests were used for categorical factors. In addition, univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to assess factors associated with occurrence of post-sphincterotomy bleeding; factors seen in < 5 patients were not considered for this part of the analysis. An automated stepwise variable selection method performed on 1000 samples was used to choose the final model. The use of SRI was forced into the models and the additional three variables with highest inclusion rates were included in the final models. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. SAS version 9.4 (The SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used to perform all analyses.

Out of 22500 who had undergone endoscopy, 447 subjects who underwent sphincterotomy were included in the study (Tables 5-7). At the time of the procedure, 219 patients were taking SRI therapy and 228 patients had never been on SRI therapy.

There was no evidence of a significant difference in the incidence of post-sphincterotomy bleeding between the groups 8.2% vs 12.3% (Table 8 and Figure 2). The absence of alcohol intake, depression, and lower PTT were significantly more common in subjects taking SRIs.

On univariable analysis, there was no evidence of an association between any of the assessed factors and post-sphincterotomy bleeding. The use of SRIs, demographic, BMI, clinical comorbidities including cardiovascular disorders, renal disease, indication of ERCP, and number of ERCPs were included in the final model but these did not reach statistical significance. None of the patients who experienced immediate post-sphincterotomy bleeding required blood transfusion therapy. Only two patients < 1% of the study group experienced delayed bleeding and did not require any transfusion. Patients who oozed blood were managed by injecting epinephrine.

It is a widely perceived, yet never before tested in patients undergoing sphincterotomy, theory that the use of SRI therapy is associated with an increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. In this retrospective cohort study, we found no significant association between the use of SRI and post-sphincterotomy bleeding. Moreover, no difference in estimated blood loss was observed in these two group. Association between percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy and SRI’s bleeding has been reported[5]; however, unlike our study, none of these studies excluded other confounding potential risk factors for bleeding. Our findings contradict the other studies that have found SRI to increase bleeding. The exact mechanism is unknown but the purported mechanism of SRI’s on bleeding states that SRI’s inhibits the serotonin transport protein and by blocking the uptake of synaptic serotonin into presynaptic neurons, it impairs the hemostasis function. SRI’s act as a blocker and inhibit entry of serotonin from blood into platelets. Release of serotonin from platelets into the bloodstream during an injury is an important step platelet aggregation[9,11-13]. This presumed mechanism can further predispose to bleeding disturbances. However, our finding did not show any evidence indicating SRI to increase bleeding.

Many studies suggest an association between SRI’s and upper gastrointestinal bleeding. It’s suggested that SRIs increase gastric acidity by targeting gastric mucosa which potentiates the risk of upper GI bleeding[9,11]. In a recent meta-analysis on risk for GI bleeds, it was noticed that patients on combined therapy such as NSAIDs, aspirin, SRIs were at higher risk for bleeding[8]. To our knowledge, only two studies have studied risk of post sphincterotomy bleeding with patients using NSAIDS and aspirin. The finding of the studies were equivocal: Both found different results suggesting the safety of aspirin use during procedure[4,6] one study results showed that use of aspirin resulted in increased risk of bleeding[6], and the other study results showed aspirin and NSAIDs not associated with the risk bleeding[4].

Drugs that cause prolonged bleeding, such as aspirin and NSAIDS are advised to discontinue a week prior to surgery. Patients who experience bleeding during the procedure are injected with epinephrine around the sphincterotomy site. This is considered to be the most commonly used method to manage immediate bleeding.

Our usual approach is local therapy in the form of 1:10000 diluted epinephrine injection, either alone or in combination with cautery, hemoclips. Covered metal stents are placed in patients who are expected to resume therapeutic anticoagulation or have underlying coagulopathy.

While recognizing that no definite guidelines can be derived from this retrospective study, our result presented here provides novel knowledge about complex question of management of SRI’s prior to therapeutic ERCP. We conclude if the confounding variables for bleeding are excluded, SRI’s alone do not increase the risk of post-sphincterotomy bleeding. According to our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the SRI’s impact on post sphincterotomy bleeding.

Since its earliest description in 1974, endoscopic sphincterotomy has become a commonly performed procedure for a variety of therapeutic indications during endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography. Including choledocholithiasis, placement of stents through malignant and benign strictures, as well as to treat dysfunction of the sphincter of Oddi.

The authors hypothesis was that serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs) medications increase the risk of post sphincterotomy bleeding.

The authors conclude if the confounding variables for bleeding are excluded, SRI’s alone do not increase the risk of post-sphincterotomy bleeding. According to our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the SRI’s impact on post sphincterotomy bleeding.

The paper of Yadav et al is original and well written. The interest to know there is no bleeding risk with SRI therapy is not so high but important to know.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Caillol F, Hlava S, Kitamura K S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Freeman ML. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy: a review. Endoscopy. 1997;29:288-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ferreira LE, Baron TH. Post-sphincterotomy bleeding: who, what, when, and how. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2850-2858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, Geenen JE, Russell RCG, Meyers WC, Liguory C, Nickl N. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: An attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:383-393. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1890] [Cited by in RCA: 2036] [Article Influence: 59.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Onal IK, Parlak E, Akdogan M, Yesil Y, Kuran SO, Kurt M, Disibeyaz S, Ozturk E, Odemis B. Do aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs increase the risk of post-sphincterotomy hemorrhage--a case-control study. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2013;37:171-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Richter JA, Patrie JT, Richter RP, Henry ZH, Pop GH, Regan KA, Peura DA, Sawyer RG, Northup PG, Wang AY. Bleeding after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy is linked to serotonin reuptake inhibitors, not aspirin or clopidogrel. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:22-34.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hui CK, Lai KC, Yuen MF, Wong WM, Lam SK, Lai CL. Does withholding aspirin for one week reduce the risk of post-sphincterotomy bleeding? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:929-936. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Tavakoli HR, DeMaio M, Wingert NC, Rieg TS, Cohn JA, Balmer RP, Dillard MA. Serotonin reuptake inhibitors and bleeding risks in major orthopedic procedures. Psychosomatics. 2012;53:559-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jiang HY, Chen HZ, Hu XJ, Yu ZH, Yang W, Deng M, Zhang YH, Ruan B. Use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:42-50.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Andrade C, Sandarsh S, Chethan KB, Nagesh KS. Serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants and abnormal bleeding: a review for clinicians and a reconsideration of mechanisms. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:1565-1575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Szary NM, Al-Kawas FH. Complications of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: how to avoid and manage them. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY). 2013;9:496-504. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Loke YK, Trivedi AN, Singh S. Meta-analysis: gastrointestinal bleeding due to interaction between selective serotonin uptake inhibitors and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:31-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Dall M, Schaffalitzky de Muckadell OB, Lassen AT, Hansen JM, Hallas J. An association between selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use and serious upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1314-1321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Dalton SO, Johansen C, Mellemkjaer L, Nørgård B, Sørensen HT, Olsen JH. Use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risk of upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding: a population-based cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:59-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 262] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |