Published online Mar 16, 2017. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v9.i3.133

Peer-review started: July 25, 2016

First decision: September 7, 2016

Revised: October 12, 2016

Accepted: December 13, 2016

Article in press: December 14, 2016

Published online: March 16, 2017

Processing time: 233 Days and 14 Hours

To determine if prophylactic clipping of post-polypectomy endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) mucosal defects of large, flat, right sided polyps prevents perforations.

IRB approved review of all colonoscopies, and prospective data collection of grasp and snare EMR performed by 2 endoscopists between January 1, 2010 and March 31, 2014 in a community ambulatory endoscopy center. The study consisted of two phases. In the first phase, all right-sided, flat polyps greater than or equal to 1.2 cm in size were removed using the grasp and snare technique. Clipping was done at the discretion of the endoscopist. In the second phase, all mucosal defects were closed using resolution clips. Phase 2 of the study was powered to detect a statistically significant difference in perforation rate with 148 EMRs, if less than or equal to 2 perforations occurred.

In phase 1 of the study, 2121 colonoscopies were performed. Seventy-five patients had 95 large polyps removed. There were 4 perforations in 95 polypectomies (4.2%). The perforations occurred in polyps ranging in size from 1.5 cm to 2.5 cm. In phase 2, there were 2464 colonoscopies performed. One hundred and sixteen patients had 151 large polyps removed, and all mucosal defects were clipped. There were no perforations (P = 0.0016). There were no post-polypectomy hemorrhages in either phase. An average of 2.15 clips were required to close the mucosal defects. The median time to perform the polypectomy and clipping was 13 min, and the median procedure duration was 40 min. Five percent of all patients undergoing colonoscopy in our community based, ambulatory endoscopy center had flat, right sided polyps greater than or equal to 1.2 cm in size.

Prophylactic clipping of the mucosal resection defect of large, right-sided, flat polyps reduces the incidence of perforation.

Core tip: Large, flat, right sided polyps are being recognized with increasing frequency, and have become one of the more technically challenging aspects of colonoscopy. In a prospective study of over 4500 consecutive colonoscopies performed in a community, ambulatory endoscopy center, the prevalence of these polyps was 5%. We showed that it was safe to remove these polyps in the outpatient setting, and that clipping the mucosal defect prevented perforations. An average of 2 clips were required to close the defects, and the average polypectomy time was 13 min. It is not necessary to perform these procedures in a hospital setting.

- Citation: Luba D, Raphael M, Zimmerman D, Luba J, Detka J, DiSario J. Clipping prevents perforation in large, flat polyps. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2017; 9(3): 133-138

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v9/i3/133.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v9.i3.133

Colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer mortality in men and women in the United States with about 132700 new cases and 49700 deaths expected in 2015. Screening colonoscopy with polypectomy has contributed to reducing deaths from colon cancer by 47%[1]. While colonoscopy is effective in reducing the incidence of left-sided colon cancer, it is not as effective for right-sided cancers[2]. Flat, right-sided colon polyps are cancer precursors and account for about 50%-55% of interval cancers[3]. Due to the flat morphology, frequent large size, and thin wall of the right colon, these polyps may be difficult to detect, challenging to remove, and associated with increased procedure-related morbidity, including bleeding and perforation[4].

Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) entails injecting a fluid matrix into the submucosal space between the lamina propria and muscularis mucosa to raise the lesion on this bleb of fluid. This allows for snare resection of the mucosal bleb that is safer, more effective and efficient than standard snare resection, particularly in the thin-walled right colon[5]. However, it may be difficult to ensnare the spreading mucosal bleb with conventional snares passed through standard single channel colonoscopes.

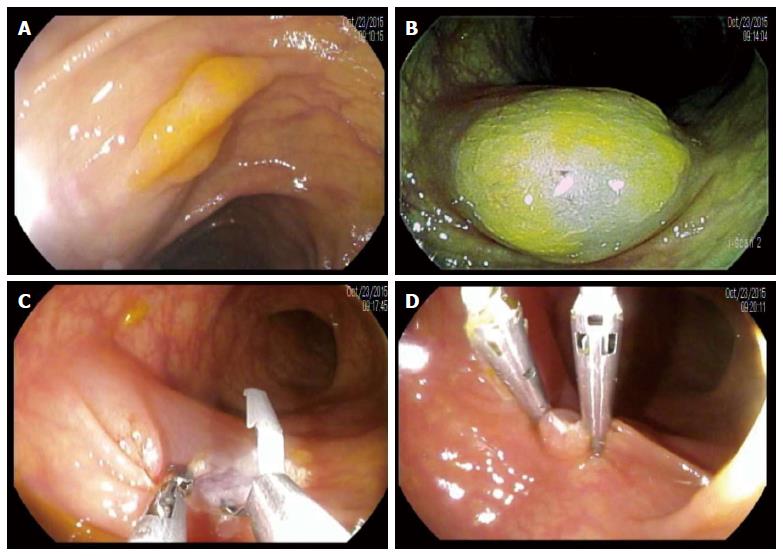

The grasp and snare EMR (GSEMR) technique entails using a double channel colonoscope with submucosal injection to raise the lesion on a mucosal bleb. A snare is inserted through one channel which is opened over the polyp and mucosal bleb and a biopsy forceps through the other channel and open snare. The polyp and mucosal bleb are grasped with a forceps and slightly retracted. The snare is closed around the raised polyp and mucosal bleb while applying monopolar energy to excise the lesion[6,7]. Clipping to close the mucosal defect can then be done as required (Figure 1).

The overall management of large flat polyps varies. Due to concerns about prolonged procedures and increased morbidity rates, some endoscopists prefer to not resect these polyps during the initial procedure. The patient is then scheduled to return for an office visit for counseling and/or a subsequent procedure in a hospital setting rather than an ambulatory endoscopy unit, or is referred for surgery[5]. Endoscopic clipping has been used to prevent and treat post-polypectomy bleeding, and close small perforations thereby avoiding surgery[4,8,9]. However, less is known about the safety and efficacy of the GSEMR technique combined with prophylactic clipping of the mucosal defect in a community ambulatory endoscopy unit. The aim of the study was to determine if prophylactic clipping of the GSEMR base prevents perforations.

This is a prospective cohort study comprised of two phases. Prior to the procedures, all patients were advised to discontinue dipyridamole for 7 d, warfarin for 4 d, and other anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents according to the prescribing provider. Two models of double channel colonoscopes were used throughout the study. The Pentax Medical (Montvale, NJ, United States) EC3890TLK has a 13.2-mm insertion tube diameter and the EC3870TLK has a 12.8-mm insertion tube diameter. Both instruments have working channels of 3.8 mm and 2.8 mm, tip angulation of 180° up/down and 160° right/left, and a 140° angle of view. All procedures were done with white light and no magnification or chromo-endoscopy. I-scan was used at the discretion of the endoscopist.

Polyps that met inclusion criteria were located proximal to the splenic flexure, 1.2 cm or larger in diameter, and had a maximum base width that was larger than the protruding height. Lesions that appeared to be malignant due to size, morphology, and/or infiltration were excluded. Eligible lesions were treated with GSEMR. Post polypectomy hemorrhage was defined as bleeding that occurred after a patient left the endoscopy center, and required evaluation at a medical office or hospital, and required blood transfusion, hospitalization or repeat colonoscopy to evaluate the polypectomy site, or control the bleeding. Perforation was defined as presence of free air on either abdominal radiographs or CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis, in conjunction with abdominal pain.

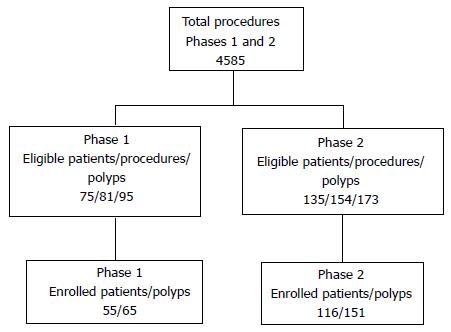

The study consisted of two phases as shown in Figure 2. During Phase 1 (February 1, 2010-September 30, 2011), the resection sites were clipped at the discretion of the endoscopists to prevent perforation and not as a routine maneuver. A total of 6 polyps were clipped in phase 1. However, 4 of 75 (5.3%) eligible patients with 95 (4.2%) eligible polyps experienced perforations at the resection site. The size of these four polyps were 2, 1.5, 2 and 2.5 cm. No target signs were appreciated. Therefore, Phase 2 (October 1, 2011-March 31, 2014) was initiated with routine endoscopic closure of the post-GSEMR mucosal defect using Resolution clips (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA). The majority of lesions were removed with piecemeal resection and retrieved by suction through the working channels into a specimen trap. Occasionally, larger specimens were retrieved using an endoscopic net. All resection sites were tattooed with India ink following GSEMR.

All colonoscopies were done at the Monterey Bay Ambulatory Endoscopy Center, LLC, a Medicare-certified unit with four endoscopy rooms, and 10 board certified gastroenterologists on staff. The study was performed in a practice that serves approximately 215250 people in Monterey County, CA. GSEMR was performed by two gastroenterologists (DGL, JAD), each with over 15 years of experience. The study population consisted of all consecutive adult patients who had colonoscopies performed by these endoscopists during the study period and had GSEMR of large, flat, right colonic polyps. All patients gave standard clinical informed consent, and those who wished to have their data included in the study gave additional research consent as shown in Figure 2.

Histopathological evaluation was done by one or more of five experienced pathologists (one with formal advanced gastroenterology pathology training) according to World Health Organization Criteria[10]. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus and/or external referral center consultation. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Community Hospital of the Monterey Peninsula, Monterey, CA, United States.

Phase 2 of the study was powered using a one stage design. The observed perforation rate using the current procedure in Phase 1 was 4.2% (4 perforations in 95 polypectomies). A sample size of n = 148 polypectomies was determined to be necessary to provide a one-sided Type I error rate α = 0.05 under the null hypothesis that the perforation rate of the new procedure is 4.2% and 80% power to detect a perforation rate of 1% or less. The null hypothesis would be rejected if there were 2 or fewer perforations out of 148 polypectomies.

Figure 2 shows a flow chart of eligible and enrolled patients. Over the 50 mo of the study, a total of 4,585 colonoscopies were performed by the two participating endoscopists. Indications for colonoscopy are shown in Table 1. In both phases, the primary indication was adenomatous polyp surveillance: 69% (Phase 1), 73% (Phase 2).

| Phase 1(n = 55) | Phase 2(n = 116) | |

| Indications for colonoscopy1 | ||

| Surveillance | 38 (69) | 85 (73) |

| Screening | 12 (21.8) | 29 (25) |

| Abdominal pain/diarrhea | 8 (14.5) | 11 (9.5) |

| Bleeding | 6 (10.9) | 7 (6) |

| Change in bowel habits | 2 (3.6) | 2 (1.7) |

| Evaluation/therapy of known lesions | 1 (1.8) | 2 (1.7) |

| Anemia | 3 (5.5) | 2 (1.7) |

| Abnormal imaging | N/A | 2 (1.7) |

| Other | 1 (1.8): Diverticulitis | 3 (2.6): Diverticulitis: 1 Rectal prolapse: 1 Rectal pain: 1 |

| Patient characteristics | ||

| Male/female (n) | 36/19 | 65/51 |

| Mean age (Range) | 69.3 (37-87) | 65.5 (29-87) |

| Family history of colon cancer | 12 (21.8) | 27 (23.3) |

| Procedure data and outcomes | ||

| Total colonoscopies | 2121 | 2464 |

| Total polyps | 65 | 151 |

| Polyp size (cm): (Mean ± SD, median, range) | 2 ± 0.69, 2, 1.2-4 | 1.81 ± 0.54, 1.6, 1.2-4 |

| Clips/polyp (Mean ± SD, median) | N/A | 2.17 + 0.97, 2 |

| Polypectomy duration (min): Mean (SD), median, range | 18.69 (15.31), 18, 2-61 | 16.4 (10.04), 13, 4-592 |

| Procedure duration (min): Mean (SD), median, range | 44.70 (18.83), 41, 14-97 | 42.90 (15.60), 40, 20-96 |

| Prevalence of large, flat right- sided polyps | 3.8% (81/2121 procedures) | 6.3% (154/2464 procedures) |

| Complications | Post-polypectomy bleeds: 0 Perforations: 2 3.6% of patients, 3% of polypectomies | Post-polypectomy bleeds: 0 Perforations: 0 |

In Phase 1, the mean procedure duration was 44.70 ± 18.83 min and the mean GSEMR time was 18.69 ± 15.31 min. The overall prevalence of eligible polyps among all patients was 3.8%. Complications included four perforations in 75 (5.3%) patients and 95 (4.2%) polypectomies. There were no post-polypectomy hemorrhages. Table 2 shows histopathology results with 31 (48%) tubular adenomas (TAs), 16 (25%) sessile serrated adenomas (SSAs), and 10 (15%) hyperplastic polyps (HPs).

| Phase 11 (n = 65) | Phase 2 (n = 151) | |

| Sessile serrated adenoma | 16 (25.0) | 68 (45.0) |

| Tubular adenoma | 31 (48.0) | 47 (31.0) |

| Hyperplastic | 10 (15.0) | 24 (16.0) |

| Tubulovillous | 7 (11.0) | 7 (5.0) |

| Normal | 1 (1.5) | 2 (1.3) |

| Fibroepithelial | 1 (1.5) | N/A |

| Lipoma | N/A | 2 (1.3) |

| Pneumatosis coli | N/A | 1 (0.7) |

In Phase 2, 2464 colonoscopies were performed. The prevalence of eligible polyps among all patients was 6.3%. Histopathology revealed SSAs 68 (45%), TAs 47 (31%), HPs 24 (16%) and TVAs 7 (5%). The mean procedure time was 42.90 ± 15.60 min. The mean polypectomy duration was 16.4 ± 10.04 min. A median of 2 clips were used to close the mucosal defects. There were no observed post-polypectomy perforations among the 151 polypectomies. Results of exact binomial test for goodness-of-fit suggests that the findings were statistically significant (P = 0.0016). We are 95% confident that the true polypectomy perforation rate for this new procedure is between 0% and 1.9% - well below the observed perforation rate using the current procedure (4.2%). We reject the null hypothesis that the perforation rate of the new procedure is no different than the current procedure (4.2%). There were no bleeding episodes.

The current study supports the hypothesis that prophylactic clipping of the mucosal defect following GSEMR of large, flat, right colonic polyps prevents perforations. The results also demonstrate that these polyps can be safely removed in an ambulatory endoscopy center as opposed to a hospital, and that these procedures do not interfere with overall patient flow in the unit. By using double channel colonoscopes and a biangulated technique, approximation of the mucosal defect can be achieved with a median of two clips per polyp and minimal prolongation of colonoscopy compared to standard EMR[11].

The initial hypothesis was that these polyps could safely be removed without using clips. However, due to the perforation rate of 4.2% in Phase 1, the second phase of the study was powered to determine whether universal clipping of the mucosal defect would decrease the perforation rate. Subsequently, there were no perforations in 151 polypectomies. This is a statistically significant difference that met the primary endpoint for Phase 2 of the study, which was then terminated per protocol. However, prospective randomized studies are required to confirm these results. In addition, there was no post-polypectomy bleeding in either phase of the study.

Two recent studies report that prophylactic clipping does not prevent bleeding or perforations, and is not a cost-effective practice[12,13]. Other studies, including a meta-analysis of eight randomized controlled trials[14], showed that prophylactic clipping reduces bleeding but not perforations[4]. The current study provides prospective data in a community setting to further identify applications for these techniques and justify larger prospective, randomized, controlled studies to validate these results.

A potential criticism of GSEMR combined with prophylactic clipping is that it prolongs procedures and interrupts patient flow. In a meta-analysis, three EMR studies reported mean procedure times of 29-30 min[11]. While all lesions in the meta-analysis were large, they were not entirely of flat morphology or right colonic location. The current study demonstrates mean procedure times of 44.7 and 42.9 min in Phase 1 and Phase 2, respectively. However, since the prevalence of these polyps was only 5.1%, we did not find doing these cases disruptive to our schedule.

Over the course of this four-year study, 5.1% of total procedures involved flat, right-sided polyps that were ≥ 1.2 cm. This compares with a 7% prevalence of flat right colonic lesions ranging from 3-40 mm in 1819 patients with 2770 lesions in a Veterans Affairs Hospital[15]. This difference in prevalence is likely due to the larger size range for eligible polyps, and patient demographics consisting of predominantly men over the age of 50 in a Veterans hospital.

The double channel endoscopes that were used had similar angulation ranges and diameters as single channel colonoscopes. Technical advances in colonoscope design are continually being made. However, the emphasis has generally been on image quality and improvement in polyp detection, rather than facilitating therapeutic maneuvers. Double channel colonoscopes allow for biangulated therapeutic maneuvers, which facilitate the removal of large, flat, right colon polyps. Only in rare cases throughout the study period was it necessary to exchange the double channel colonoscope for a pediatric colonoscope, which also occurs with standard colonoscopes. Design enhancements, combined with the development of accessories that facilitate a biangulated or triangulated approach to therapeutic interventions will improve the functional aspects of the currently available instruments.

Large, flat right-sided polyps occurred in 5.1% of patients during the study period. Based on the procedure times and similarities in functionality between double and single channel colonoscopes, removal of these challenging lesions is feasible and safe in a community endoscopy center and does not necessitate performance of the procedure in a hospital setting. Clipping the post-polypectomy defect reduces the perforation rate.

Large, flat, right sided polyps are cancer precursors, and are increasingly found during colonoscopy. These polyps are challenging to remove, and are frequently either removed in a hospital setting or referred to an expert endoscopist. Removing these polyps during an initial outpatient colonoscopy would decrease the number of procedures performed, and be more cost effective.

More research should be done with double channel colonoscopes to enable biangulated and triangulated approaches to therapeutic endoscopy.

Utilizing a double-channel colonoscope, it is possible to approximate the edges of a mucosal defect with a biopsy forceps, and then close the defect with a clip.

By utilizing double channel colonoscopes, large, flat polyps can be removed in a safe and cost effective manner in an outpatient setting. Clipping the post-polypectomy defect, reduces the risk of perforation.

Interesting article. As correctly quoted by the authors, multiple studies in the recent past have not shown significant benefit for prophylactic clipping to prevent perforations. It is important to know if there was a difference in size of the polyps resected by GSEMR between the 2 groups rather than just noting the polyps were greater than 1.2 cm for study inclusion.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Herman RD, Rastogi A, Zhang QS S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9172] [Cited by in RCA: 9954] [Article Influence: 995.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hewett DG, Rex DK. Miss rate of right-sided colon examination during colonoscopy defined by retroflexion: an observational study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:246-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Samadder NJ, Curtin K, Tuohy TM, Pappas L, Boucher K, Provenzale D, Rowe KG, Mineau GP, Smith K, Pimentel R. Characteristics of missed or interval colorectal cancer and patient survival: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:950-960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Liaquat H, Rohn E, Rex DK. Prophylactic clip closure reduced the risk of delayed postpolypectomy hemorrhage: experience in 277 clipped large sessile or flat colorectal lesions and 247 control lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:401-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wallace M. Removal of Flat and Large Polyps. ACG. 2014;Postgraduate Course, 2014. |

| 6. | Akahoshi K, Kojima H, Fujimaru T, Kondo A, Kubo S, Furuno T, Nakanishi K, Harada N, Nawata H. Grasping forceps assisted endoscopic resection of large pedunculated GI polypoid lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:95-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | de Melo SW, Cleveland P, Raimondo M, Wallace MB, Woodward T. Endoscopic mucosal resection with the grasp-and-snare technique through a double-channel endoscope in humans. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:349-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Parra-Blanco A, Kaminaga N, Kojima T, Endo Y, Uragami N, Okawa N, Hattori T, Takahashi H, Fujita R. Hemoclipping for postpolypectomy and postbiopsy colonic bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:37-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Buchner AM, Guarner-Argente C, Ginsberg GG. Outcomes of EMR of defiant colorectal lesions directed to an endoscopy referral center. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:255-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bosman FT, WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer. Lyon: IARC Press 2010; . |

| 11. | Fujiya M, Tanaka K, Dokoshi T, Tominaga M, Ueno N, Inaba Y, Ito T, Moriichi K, Kohgo Y. Efficacy and adverse events of EMR and endoscopic submucosal dissection for the treatment of colon neoplasms: a meta-analysis of studies comparing EMR and endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:583-595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 268] [Article Influence: 26.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Feagins LA, Nguyen AD, Iqbal R, Spechler SJ. The prophylactic placement of hemoclips to prevent delayed post-polypectomy bleeding: an unnecessary practice? A case control study. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:823-828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Quintanilla E, Castro JL, Rábago LR, Chico I, Olivares A, Ortega A, Vicente C, Carbó J, Gea F. Is the use of prophylactic hemoclips in the endoscopic resection of large pedunculated polyps useful? A prospective and randomized study. J Interv Gastroenterol. 2012;2:183-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Li LY, Liu QS, Li L, Cao YJ, Yuan Q, Liang SW, Qu CM. A meta-analysis and systematic review of prophylactic endoscopic treatments for postpolypectomy bleeding. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26:709-719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Soetikno RM, Kaltenbach T, Rouse RV, Park W, Maheshwari A, Sato T, Matsui S, Friedland S. Prevalence of nonpolypoid (flat and depressed) colorectal neoplasms in asymptomatic and symptomatic adults. JAMA. 2008;299:1027-1035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 453] [Cited by in RCA: 433] [Article Influence: 25.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |