Published online Jan 16, 2017. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v9.i1.26

Peer-review started: July 1, 2016

First decision: August 22, 2016

Revised: September 17, 2016

Accepted: October 17, 2016

Article in press: October 19, 2016

Published online: January 16, 2017

Processing time: 188 Days and 1.6 Hours

To evaluate the rate of recurrence of symptomatic choledocholithiasis and identify factors associated with the recurrence of bile duct stones in patients who underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) for bile duct stone disease.

All patients who underwent ERCP and EST for bile duct stone disease and had their bile duct cleared from 1/1/2005 until 31/12/2008 was enrolled. All symptomatic recurrences during the study period (until 31/12/2015) were recorded. Clinical and laboratory data potentially associated with common bile duct (CBD) stone recurrence were retrospectively retrieved from patients’ files.

A total of 495 patients were included. Sixty seven (67) out of 495 patients (13.5%) presented with recurrent symptomatic choledocholithiasis after 35.28 ± 16.9 mo while twenty two (22) of these patients (32.8%) experienced a second recurrence after 35.19 ± 23.2 mo. Factors associated with recurrence were size (diameter) of the largest CBD stone found at first presentation (10.2 ± 6.9 mm vs 7.2 ± 4.1 mm, P = 0.024), diameter of the CBD at the first examination (15.5 ± 6.3 mm vs 12.0 ± 4.6 mm, P = 0.005), use of mechanical lithotripsy (ML) (P = 0.04) and presence of difficult lithiasis (P = 0.04). Periampullary diverticula showed a trend towards significance (P = 0.066). On the contrary, number of stones, angulation of the CBD, number of ERCP sessions required to clear the CBD at first presentation, more than one ERCP session needed to clear the bile duct initially and a gallbladder in situ did not influence recurrence.

Bile duct stone recurrence is a possible late complication following endoscopic stone extraction and CBD clearance. It appears to be associated with anatomical parameters (CBD diameter) and stone characteristics (stone size, use of ML, difficult lithiasis) at first presentation.

Core tip: Recurrence of choledocholithiasis is considered a late complication following endoscopic extraction of bile duct stones. There are various factors associated with the risk of recurrence. In our study the rate of recurrence was 13.5%. Although univariate analysis identified four different risk factors associated with both anatomical parameters (common bile duct diameter) and stone characteristics (stone size, use of mechanical lithotripsy, difficult lithiasis), multivariate analysis confirmed only bile duct diameter as being important. The underlying pathogenetic mechanism of recurrence is likely multifactorial in nature. Bile stasis, duodenal - biliary reflux and unfavorable stone characteristics probably contribute towards stone reformation.

- Citation: Konstantakis C, Triantos C, Theopistos V, Theocharis G, Maroulis I, Diamantopoulou G, Thomopoulos K. Recurrence of choledocholithiasis following endoscopic bile duct clearance: Long term results and factors associated with recurrent bile duct stones. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2017; 9(1): 26-33

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v9/i1/26.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v9.i1.26

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is widely accepted as the modality of choice for the endoscopic removal of bile duct stones. Endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) since its introduction in 1974[1,2], has been extensively used for the endoscopic extraction of bile duct stones. Endoscopic techniques for stone removal are generally considered both safe and effective but, their invasive nature cannot preclude the possibility of complications. In fact complications can occur even in the hands of the most seasoned expert[3]. They can be broadly classified, depending on their timing, as early (up to 3 d post-procedure) or late (> 3 d)[4]. Early complications are mostly related with sedation and endoscopy like bleeding, infection, pancreatitis, perforation, cardiopulmonary events, while late complications concern mainly stent infections due to long-term/permanent stent deployment and post-procedural duct/sphincter of Oddi (SO) inflammatory changes (i.e., ampullary stenosis) because of ductal/SO manipulation[4]. Although not officially listed as a late complication of ERCP in various guidelines[3], recurrence of choledocholithiasis is considered to be one by many authors[5-7]. Rates of recurrence vary across different studies, ranging from 4% to 24% (variable intervals of follow-up of up to 15 years)[8-10]. The goal of this paper is to evaluate the rate of recurrence of symptomatic choledocholithiasis and identify factors associated with the recurrence of bile duct stones in patients who underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) for bile duct stone disease.

We retrospectively studied a group of patients who underwent ERCP and EST for bile duct stone disease at a tertiary center, Department of Gastroenterology of the University hospital of Patras from 1/1/2005 until 31/12/2008. Only patients in whom complete and successful clearance of the common bile duct (CBD) from stones was achieved were included in the study irrespectively of the number of sessions required to fulfill that requirement. Patients with difficult bile duct stones (large bile duct stones (> 10 mm) and/or multiple stones (≥ 3) or impacted stones)[11] or residual choledocholithiasis were included in the study as long as a patent CBD was achieved in their baseline or any of their subsequent follow-up examinations. Patients with known residual CBD stones (unable to be extracted or referred for surgical treatment), pancreatic/biliary malignant disorders and benign biliary strictures (usually post - surgery) were excluded from the study, finally patients with indwelling biliary stents (permanent or long standing) and patients that were lost to follow - up were also excluded. Every patient with gallbladder stones was instructed to remove his/her gallbladder surgically after the first (baseline) clearance of the bile duct (if a cholocystectomy was not already performed). All patients were followed up until either termination of the study (31/12/2015) or when they died.

For the purpose of studying recurrence associated risk factors we created two (2) groups. In the first group all patients with a history of symptomatic recurrence were enrolled (after applying exclusion criteria). An equal number (1:1) of age / gender - matched control patients was selected from the pool of recurrent free patients (group two).

Written informed consent for the ERCP was obtained from all the patients undergoing the procedure. Preparation included local anesthesia of the pharynx using 10% xylocaine, and conscious sedation of the patient with the use of (IV) midazolam - pethidine. Reversal agents (flumazenil) were used when indicated. Antibiotic prophylaxis was used in accordance with published guidelines at the time, the exact regimen depending on the appropriate clinical indication[12]. ERCP was performed using a side-view endoscope (Olympus Optical Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). In patients with native papilla EST was performed, after deep canullation of the CBD with the help of a guidewire, using a standard pull-type papillotome according to the standard technique. Before performing the EST a cholangiogram (using a diluted contrast medium) was attainted to confirm CBD stones. Under fluoroscopic/endoscopic guidance stones were removed from the CBD, mainly with the use of ballon catheters and occasionally with dormia retrieval baskets. Patients with difficult stones were treated with either mechanical lithotripsy at the same session or use of temporary plastic stents. Patency of the CBD/clearance of stones was evaluated by absence of any filling defects at the final cholangiogram. During the enrollment period (2005-2008) large balloon dilation was not a common practice. As such it was not exercised by our unit.

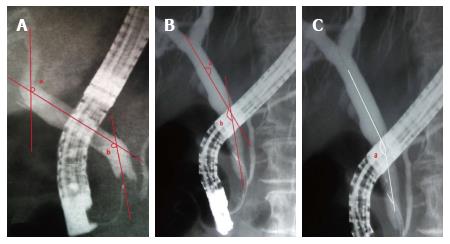

Size and number of CBD stones were assessed on the cholangiogram after optimum opacification of the CBD. Stone size was assessed by comparing the diameter of the stone to the (relevant size of the) shaft of the endoscope on the cholangiogram. CBD diameter was measured in a similar manner. Likewise CBD angulation(s) were also calculated from postoperative cholangiograms. All calculations were independently validated by a second observer and any interobserver differences were expressed as mean values.

All data was extracted from the first (baseline) ERCP of all patients.

The following parameters were recorded and investigated for the purpose of studying risk factors. (1) Basic demographics: sex and age; (2) Diameter of the CBD (mm); (3) Stone characteristics: Size (mm) (defined as the diameter of the largest stone), number of stones, difficult CBD lithiasis (defined as presence of large bile duct stone (> 10 mm) and/or multiple stones (≥ 3) and/or impacted stones[11]); (4) Angulation of the CBD: Two (2) different angulation scores were assessed (Figure 1)[13,14]; (5) Juxtapapillary duodenal diverticula; (6) Timing of recurrences (early vs late); (7) Use of mechanical lithotripsy (ML); (8) Number of ERCP session required to clear the Bile Duct; and (9) Past medical history: Surgical (mainly hepatobililiary/pancreatic): (1) Biliary - enteric anastomosis (BEA); (2) Altered stomach anatomy (gastrectomy or other); and (3) Cholocystectomy/remaining gallbladder (gallbladder that was not surgically removed, termed gallbladder in situ)/gallbladder stones (chololithiasis).

Stone recurrence, for the purpose of this study, was defined by the confirmation of the presence of a CBD stone in the appropriate clinical context at least 6 mo after previous (complete) CBD stone removal by ERCP was achieved. Thus we evaluated only clinically significant recurrences (patients exhibiting relevant hepatobiliary symptoms like pain and jaundice).

Multiple recurrences were defined as 2 or more stone recurrences after the first ERCP. In this study early recurrence was defined as a recurrence that occurred up to (and including) 24 mo after the baseline ERCP that CBD patency was achieved (this term applies only to first recurrence episodes). A recurrence after the first 24 month was termed a late one.

Clinical and laboratory data potentially associated with common bile duct (CBD) stone recurrence were retrospectively retrieved from patients’ files. Our department belongs in a tertiary hospital. Our hepatobiliary unit acts as regional referral center. The likelihood of patients being referred to another unit would be truly improbable.

Clinical and ERCP related factors that might have contributed to the recurrence of common bile duct stones were evaluated. All these parameters were correlated with recurrence, initially by using univariate analysis. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD and were compared by using Student’s t-test. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages and differences between groups were tested for significance by using the χ2 test. Variables found to be significant in the univariate analysis (P-value less than 0.05) were included in a multivariate stepwise logistic regression model. All analyses were conducted by using statistical software SPSS, version 20 (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL, United State).

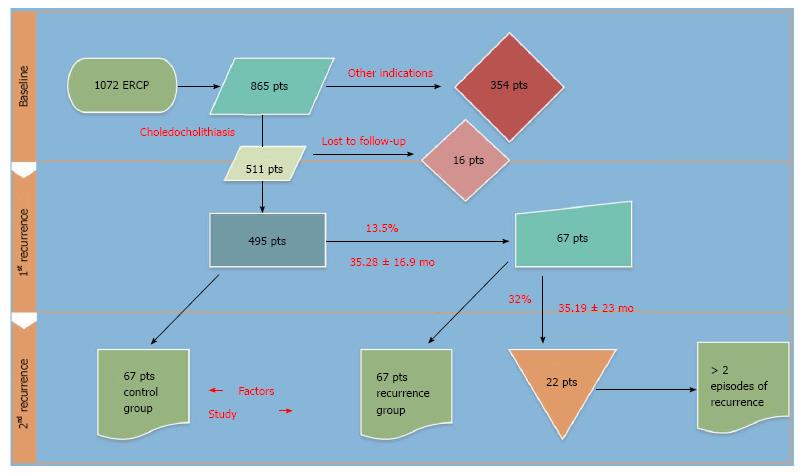

Between January 2005 and (including) December 2008, 511 unique patients were treated in our center for choledocholithiasis/microcholedocholithiasis (Figure 2). All symptomatic recurrences for the study period (until December 2015) were recorded, after applying exclusion criteria. Sixteen patients that were lost to follow - up were dropped from the study. Sixty-seven (67) out of 495 patients (13.5%) presented with recurrent symptomatic choledocholithiasis after 35.28 ± 16.909 (7-96) mo while twenty-two (22) of these patients (32.83% of the recurrent) experienced a second recurrence after 35.19 ± 23.22 (9-78) mo. A 3rd recurrence occurred to 6 (8.9%) of the recurrent patients at 16.83 ± 15.3 mo (Table 1).

| No. of recurrences | Patients (n = 67) n (%) |

| 1 | 45 (67.1) |

| 2 | 16 (23.8) |

| 3 | 4 (5.9) |

| 4 | 1 (1.5) |

| 5 | 1 (1.5) |

The number of procedures/ERCPs required to treat the recurrent population (baseline ERCP, recurrence examinations including any follow-up procedures that were required to achieve CDB patency) is summarized in Table 2. An impressive total of 199 ERPCs was required to treat the 67 recurrent patients over time. On the other hand for the 67 controls a total of 89 ERCP sessions was needed.

| No. of ERCP sessions | Patients (n = 67) n (%) |

| 2 | 31 (46) |

| 3 | 16 (23.8) |

| 4 | 13 (19) |

| 5 | 5 (7.46) |

| 6 | 2 (2.98) |

Early recurrences (recurrence during the first 24 mo after the baseline ERCP) occurred in 21/67 patients (46/67 late).

Multiple recurrences occurred in 22 patients (Table 1). We have found that an early recurrence predisposes to multiple recurrences more often than a late one. Thirteen (13) out of the 21 early recurrent patients (13/21) had a second recurrence, while only 14/46 of those with late recurrence suffered from a second episode (P = 0.0025).

For the purpose of studying risk factors, the 67 patients with a history of symptomatic recurrence were compared to a group of 67 age/gender - matched control patients that were selected from a pool of 428 patients with a recurrent free history. Baseline characteristics for both groups are presented in Table 3.

| Variable | Recurrence group (n = 67) | Control group (n = 67) | P value |

| Age, yr | 71.2 ± 12.4 | 71.9 ± 12.6 | 0.82 |

| Sex, male | 26/67 | 28/67 | 0.86 |

| History of cholecystectomy before first ERCP | 37 | 40 | 0.73 |

| BEA/gastric surgery | 4 | 2 | 0.68 |

| (2 billroth, 2 BEA) | (1 billroth, 1 BEA) | ||

| Mean follow-up time, mo | 70,1 ± 31.7 | 68.5 ± 36.1 | 0.8 |

| (2-121) | (1-129) |

No significant differences were found with regard to age, sex, previous surgical history (including cholecystectomy before the baseline (first) ERCP and biliary, gastric surgery) and mean follow -up time between the groups.

Table 4 summarizes the risk factors for recurrence that were evaluated.

| Variable | Recurrence group (n = 67) | Control group (n = 67) | P value |

| Stone size, mm | 11.0 ± 7.0 | 7.5 ± 4.5 | 0.007 |

| Stone number, n | 4.9 ± 4.4 | 4.3 ± 4.7 | 0.53 |

| CBD diameter, mm | 16.03 ± 6.1 | 12.0 ± 4.6 | 0.001 |

| CBD angulation method 1 (accumulative score) | 303.97 ± 34.41 | 304.84 ± 31.61 | 0.91 |

| CBD angulation method 2 (minimal angle score) | 137.03 ± 17.0 | 138.41 ± 14.18 | 0.71 |

| Difficult bile duct stones | 24 | 14 | 0.04 |

| Use of mechanical lithotripsy | 13 | 5 | 0.04 |

| No. of ERCP sessions required to clear the bile duct | 1.33 ± 0.6 | 1.34 ± 0.7 | 0.95 |

| More than one ERCP needed to clear the bile duct initially | 14 | 11 | 0.43 |

| Gallbladder in situ | 2 | 5 | 1 |

| Periampullary diverticula | 25 | 16 | 0.066 |

Logistic regression analyses were performed to identify the risk factors for stone recurrence, including both baseline characteristics and ERCP-related parameters. Univariate analysis revealed that diameter of the CBD, size (diameter) of the largest CBD stone, use of ML and difficult lithiasis were associated with stone recurrence. Multivariate analysis revealed that CBD diameter was the only independent risk factor associated with CBD stone recurrence (OR = 1.116, 95%CI: 1.005-1.277, P = 002).

The recurrence of CBD stones is a possible outcome following endoscopic clearance[5,6]. Rates of recurrence in the literature vary with some authors estimating them being as high as 24%[8-10]. So although it is considered a late complication of stone extraction, it certainly is not a rare one. Many authors report that most recurrences of bile duct stones take place in the first 3 years[15,16], the limit between recurrence and residual stone disease is somewhat arbitrary with many authors advocating for the threshold of 5[16] to 6[15] mo.

Bile duct stones (and as a result also recurrent stones) are classified as primary or secondary stones, both with different pathogenesis and etiologies[17]. A stone is termed primary when located at the site of its formation, while a secondary stone is a stone that has migrated from the site of its origin (in this case usually the gallbladder). Thus, primary CBD stones form de novo in the CBD, these are usually brown pigment (calcium bilirubinate) stones, where they remain either uneventfully or until they are implicated in a clinical sequela (e.g., cholangitis)[18]. Secondary CBD stones are commonly associated with migrating gallbladder (or rarely intrahepatic) stones and thus consist mainly of cholesterol.

There’s a plethora of risk factors related with recurrence of choledocholithiasis proposed in the literature; many of these are summarized in Table 5.

| Proposed risk factor | Ref. | Comment section |

| DBR | [19-21] | DBR |

| Pneumobilia | [19] | Indicative of DBR |

| Acute distal CBD angulation | [19] | Promotes bile stasis |

| CBD dilation | [19] | Promotes bile stasis |

| Periampullary diverticulum | [19] | Promotes bile stasis |

| Prior EST | [22,23] | Promotes DBR |

| Intact gallbladder with stones in situ | [22] | (Secondary) stone CBD migration |

| Billiary stricture | [22] | Promotes bile stasis |

| Papillary stenosis | [22] | Promotes bile stasis |

| ML | [22] | Small residual microlithiasis acts as nidi for stone formation |

| Stone size | [24] | Size of the largest stone |

| Cirrhosis | [22] | Delayed biliary emptying/bile stasis |

| Delayed biliary emptying | [22] | Promotes bile stasis |

| Bacterial infection/colonization of the CBD. Bacterial count | [25,26] | Promotes chronic infection, and inflammation, promotes stone formating |

| Impaired biliary flow | [25] | Scintigraphic study |

| Cholecystectomy (without stones) | [27] | Impede flushing of nidus/residual stones |

| Post-procedural sphincter function impaired | [6,27] | EST vs EPBD/EPLBD vs EPSBD, promote DBR |

| Number of sessions to clear duct at first presentation | [6] | # of ERCPs required to achieve a patent CBD |

| Age | [6] | Old age |

| Previous cholecystectomy (open or lap) | [6] | |

| Serum lvls of chol | [24] | Lithogenic properties |

| EST size | [24] | Minimal size is protective |

| Inflammation CBD | [24] | |

| Parasites of the CBD | [24] | Parasitic infection |

| Foreign bodies in the CBD | [24] | |

| Concurrent cholecystolithiasis and cholelithiasis | [28] | |

| Post stone removal CBD diameter | [21] | At 72 h after stones removal, cholangiogram via nasobiliary tube |

| EPLBD > 10 mm | [29] | Disruption of SO, DBR |

| Variations of the ABCB4, ABCB11 genes | [30] | Affect composition of bile. Associated with cholestasis, cholelithiasis and formation of primary intrahepatic stones |

| Excessive dilation of the CBD | [31] | Recurrence rate was 40% when maximum CBD diameter was more than 20 mm, whereas recurrence rate was 18% when maximum CBD diameter was 20 mm or less |

The putative mechanism responsible for stone recurrences still eludes us. In some cases, like secondary CBD stones in patients with concurrent chololithiasis, the underlying cause is in most probability also the most obvious one (i.e., stone migration from the stone-ridden gallbladder to the CBD). After reviewing the literature it is obvious that there is no consensus reached in the scientific community on the exact mechanism. We could argue that at the present there are two dominating theories.

The term endobiliary bile stasis encloses a variety of risk factors that predispose to biliary stasis, delayed biliary emptying and/or impaired biliary flow. Acute distal CBD angulation, oblique CBD angulation, CBD dilation, periampullary diverticula, billiary strictures, papillary stenosis, cirrhosis, cholocystectomy, possibly genetic factors (like variations of the ABCB4, ABCB11 genes) have been associated with biliary stasis and the formation of primary CBD stones and their recurrence. Mechanical obstruction/blockage as well as variations in the (patho)physiology of bile secretion (bile viscosity, bile secretion rate, loss of bile flushing due to cholocystectomy) could help to explain why a bile duct system exhibiting any number of these anatomic/physiology abnormalities could be predisposed to stone recurrence.

This term encompasses a number of factors that are associated with the reflux of enteric contents (fluid and/or solid chime) inside the biliary tract. Pneumobilia[19], post-procedural impaired sphincter function (EST/EPLBD), bacterial infection/colonization of the CBD, EST size are all factors that have been related to duodenal reflux. Recent studies have drawn our focus towards the role that post - procedural sphincter functional adequacy has in Duodenal - Biliary Reflux (DBR) in particular and in stone recurrence in general. It has been suggested that sphincter preserving procedures (small size EST, EPSBD) exert a protective role, reducing the risk of recurrence. Permanent sphincter function disruption by EST or EPLBD could result in duodenobiliary reflux.

The underlying pathogenesis of stone recurrence is not yet fully elucidated. To a great extent clinical practice has proceeded basic research[32]. A multifactorial model where chronic inflammation of the bile ducts plays a central role could help to better explain it. Bile stagnation, reflux of duodenal content, bacterial colonization and chronic infection of the CBD as well as mechanical and chemical damaging effects of chronic irritants (from the enteric content) could all contribute to sustain chronic inflammation[25,26].

In our study we found that CBD dilation, stone size at first presentation, difficult lithiasis and use of mechanical lithotripsy were all risk factors for stone recurrence in the univariate analysis. These findings are similar to those of previous reports[6,19,22,24,31]. We could argue that large stone size, presence of difficult lithiasis and need for mechanical lithotripsy is all different aspects of the same factor. In a way they serve to prove that patients with certain “unfavorable stone characteristics’’ recur more often than others. Multivariate analysis revealed that the diameter of the common bile duct was the only independent risk factor associated with stone recurrence. It has been suggested before that CBD dilation above a certain threshold (13 mm)[21] and especially excessive dilation (> 20 mm)[31] predispose to stone reformation. In our study, the issue of a cut-off value of CBD diameter that predisposes to higher rates of recurrence was addressed but we did not reach a statistically significant result (probably due to the sample size). Periampullary diverticula showed a trend towards significance in our study (P = 0.066), unlike the clear association reported by other authors[19,29]. This is probably so because of the small sample in our study.

It has been proposed that patients with recurring CBD stones are at increased risk for a subsequent recurrence[7]. Data from our study is also in support. Patients who suffered from a recurrence were in a much greater danger. Thirty-two percent of the recurrent population had at least a second episode, while the recurrence rate for a patient who has not experienced a recurrence before was 13.5%. Data from the aforementioned study[7] identified an interval of ≤ 5 years between initial EST and repeat ERCP as a risk factor for re - recurrence. Likewise, patients from our cohort who suffered from an early (≤ 24 mo) recurrence attack, were at increased risk for consequent episodes.

There are several limitations in this study including its retrospective design, single-center site and the relative small sample size. We acknowledge that because of both the retrospective design and the often asymptomatic nature of CBD stones, several methodological issues concerning mainly the follow-up of patients and data collection could arise. A prospective multi center cohort study needs to be conducted to investigate further the association between these risks factors and stone recurrence. This study needs to be powered by both a large sample size and a long follow-up (longer than five years)[29]. Last but not least future studies need to focus more on possible clinical applications. Bedside questions that need to be answered like which patients should we follow-up? Is there any patient group with specific characteristics (e.g., CBD dilation above a certain threshold) that justify more intensive follow-up? What is the importance of asymptomatic stones in multi-recurring patients, can these patients benefit from pre-emptive/prophylactic ERCP, what’s the hazard/benefit ratio?

In conclusion, bile duct stone recurrence is a likely late complication following endoscopic stone extraction and CBD clearance. In our study the rate of recurrent symptomatic choledocholithiasis was 13.5%. It appears to be associated with both anatomical parameters (CBD diameter) and stone characteristics (stone size, use of ML, difficult lithiasis) at first presentation.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is widely accepted as the modality of choice for the endoscopic removal of bile duct stones. Endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) since its introduction in 1974, has been extensively used for the endoscopic extraction of bile duct stones. Endoscopic techniques for stone removal are generally considered both safe and effective but, their invasive nature cannot preclude the possibility of complications.

Many authors report that most recurrences of bile duct stones take place in the first 3 years the limit between recurrence and residual stone disease is somewhat arbitrary with many authors advocating for the threshold of 5 to 6 mo.

In this study, the issue of a cut-off value of common bile duct diameter that predisposes to higher rates of recurrence was addressed but the authors did not reach a statistically significant result (probably due to the sample size). Periampullary diverticula showed a trend towards significance in the study (P = 0.066), unlike the clear association reported by other authors.

This manuscript is very well designed, the authors did a great effort in selecting the articles to be included in the meta-analysis with a proper quality scoring of selected articles. This manuscript is suitable for publication.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Greece

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Lai KH, Pan H S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Classen M, Demling L. [Endoscopic sphincterotomy of the papilla of vater and extraction of stones from the choledochal duct (author’s transl)]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1974;99:496-497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 469] [Cited by in RCA: 391] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kawai K, Akasaka Y, Murakami K, Tada M, Koli Y. Endoscopic sphincterotomy of the ampulla of Vater. Gastrointest Endosc. 1974;20:148-151. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Anderson MA, Fisher L, Jain R, Evans JA, Appalaneni V, Ben-Menachem T, Cash BD, Decker GA, Early DS, Fanelli RD. Complications of ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:467-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 281] [Cited by in RCA: 299] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Silviera ML, Seamon MJ, Porshinsky B, Prosciak MP, Doraiswamy VA, Wang CF, Lorenzo M, Truitt M, Biboa J, Jarvis AM. Complications related to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: a comprehensive clinical review. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2009;18:73-82. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Cheon YK, Lehman GA. Identification of risk factors for stone recurrence after endoscopic treatment of bile duct stones. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:461-464. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Kim KY, Han J, Kim HG, Kim BS, Jung JT, Kwon JG, Kim EY, Lee CH. Late Complications and Stone Recurrence Rates after Bile Duct Stone Removal by Endoscopic Sphincterotomy and Large Balloon Dilation are Similar to Those after Endoscopic Sphincterotomy Alone. Clin Endosc. 2013;46:637-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sugiyama M, Suzuki Y, Abe N, Masaki T, Mori T, Atomi Y. Endoscopic retreatment of recurrent choledocholithiasis after sphincterotomy. Gut. 2004;53:1856-1859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, Moore JP, Fennerty MB, Ryan ME, Shaw MJ. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1716] [Cited by in RCA: 1689] [Article Influence: 58.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 9. | Prat F, Malak NA, Pelletier G, Buffet C, Fritsch J, Choury AD, Altman C, Liguory C, Etienne JP. Biliary symptoms and complications more than 8 years after endoscopic sphincterotomy for choledocholithiasis. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:894-899. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Hawes RH, Cotton PB, Vallon AG. Follow-up 6 to 11 years after duodenoscopic sphincterotomy for stones in patients with prior cholecystectomy. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:1008-1012. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Ding J, Li F, Zhu HY, Zhang XW. Endoscopic treatment of difficult extrahepatic bile duct stones, EPBD or EST: An anatomic view. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;7:274-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Khashab MA, Chithadi KV, Acosta RD, Bruining DH, Chandrasekhara V, Eloubeidi MA, Fanelli RD, Faulx AL, Fonkalsrud L, Lightdale JR. Antibiotic prophylaxis for GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:81-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 24.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 13. | Seo DB, Bang BW, Jeong S, Lee DH, Park SG, Jeon YS, Lee JI, Lee JW. Does the bile duct angulation affect recurrence of choledocholithiasis? World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4118-4123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Keizman D, Shalom MI, Konikoff FM. An angulated common bile duct predisposes to recurrent symptomatic bile duct stones after endoscopic stone extraction. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1594-1599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tanaka M, Takahata S, Konomi H, Matsunaga H, Yokohata K, Takeda T, Utsunomiya N, Ikeda S. Long-term consequence of endoscopic sphincterotomy for bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:465-469. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Lai KH, Lo GH, Lin CK, Hsu PI, Chan HH, Cheng JS, Wang EM. Do patients with recurrent choledocholithiasis after endoscopic sphincterotomy benefit from regular follow-up? Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:523-526. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Kim DI, Kim MH, Lee SK, Seo DW, Choi WB, Lee SS, Park HJ, Joo YH, Yoo KS, Kim HJ. Risk factors for recurrence of primary bile duct stones after endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:42-48. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Saharia PC, Zuidema GD, Cameron JL. Primary common duct stones. Ann Surg. 1977;185:598-604. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Zhang R, Luo H, Pan Y, Zhao L, Dong J, Liu Z, Wang X, Tao Q, Lu G, Guo X. Rate of duodenal-biliary reflux increases in patients with recurrent common bile duct stones: evidence from barium meal examination. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:660-665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ando T, Tsuyuguchi T, Okugawa T, Saito M, Ishihara T, Yamaguchi T, Saisho H. Risk factors for recurrent bile duct stones after endoscopic papillotomy. Gut. 2003;52:116-121. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Baek YH, Kim HJ, Park JH, Park DI, Cho YK, Sohn CI, Jeon WK, Kim BI. [Risk factors for recurrent bile duct stones after endoscopic clearance of common bile duct stones]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2009;54:36-41. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Tsai TJ, Lai KH, Lin CK, Chan HH, Wang EM, Tsai WL, Cheng JS, Yu HC, Chen WC, Hsu PI. Role of endoscopic papillary balloon dilation in patients with recurrent bile duct stones after endoscopic sphincterotomy. J Chin Med Assoc. 2015;78:56-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Itokawa F, Itoi T, Sofuni A, Kurihara T, Tsuchiya T, Ishii K, Tsuji S, Ikeuchi N, Umeda J, Tanaka R. Mid-term outcome of endoscopic sphincterotomy combined with large balloon dilation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:223-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Mu H, Gao J, Kong Q, Jiang K, Wang C, Wang A, Zeng X, Li Y. Prognostic Factors and Postoperative Recurrence of Calculus Following Small-Incision Sphincterotomy with Papillary Balloon Dilation for the Treatment of Intractable Choledocholithiasis: A 72-Month Follow-Up Study. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:2144-2149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ishiguro J. Biliary bacteria as an indicator of the risk of recurrence of choledocholithiasis after endoscopic sphincterotomy. Diagn Ther Endosc. 1998;5:9-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kim KH, Rhu JH, Kim TN. Recurrence of bile duct stones after endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation combined with limited sphincterotomy: long-term follow-up study. Gut Liver. 2012;6:107-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lai KH, Chan HH, Tsai TJ, Cheng JS, Hsu PI. Reappraisal of endoscopic papillary balloon dilation for the management of common bile duct stones. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;7:77-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Lu Y, Wu JC, Liu L, Bie LK, Gong B. Short-term and long-term outcomes after endoscopic sphincterotomy versus endoscopic papillary balloon dilation for bile duct stones. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;26:1367-1373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Chang JH, Kim TH, Kim CW, Lee IS, Han SW. Size of recurrent symptomatic common bile duct stones and factors related to recurrence. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2014;25:518-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Pan S, Li X, Jiang P, Jiang Y, Shuai L, He Y, Li Z. Variations of ABCB4 and ABCB11 genes are associated with primary intrahepatic stones. Mol Med Rep. 2015;11:434-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Paik WH, Ryu JK, Park JM, Song BJ, Kim J, Park JK, Kim YT. Which is the better treatment for the removal of large biliary stones? Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation versus endoscopic sphincterotomy. Gut Liver. 2014;8:438-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Hisatomi K, Ohno A, Tabei K, Kubota K, Matsuhashi N. Effects of large-balloon dilation on the major duodenal papilla and the lower bile duct: histological evaluation by using an ex vivo adult porcine model. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:366-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |