Published online Jan 16, 2017. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v9.i1.19

Peer-review started: June 16, 2016

First decision: July 20, 2016

Revised: August 18, 2016

Accepted: November 1, 2016

Article in press: November 3, 2016

Published online: January 16, 2017

Processing time: 203 Days and 3.3 Hours

To investigate the current management of gastric antral webs (GAWs) among adults and identify optimal endoscopic and/or surgical management for these patients.

We reviewed our endoscopy database seeking to identify patients in whom a GAW was visualized among 24640 esophagogastroduodenoscopies (EGD) over a seven-year period (2006-2013) at a single tertiary care center. The diagnosis of GAW was suspected during EGD if aperture size of the antrum did not vary with peristalsis or if a “double bulb” sign was present on upper gastrointestinal series. Confirmation of the diagnosis was made by demonstrating a normal pylorus distal to the GAW.

We identified 34 patients who met our inclusion criteria (incidence 0.14%). Of these, five patients presented with gastric outlet obstruction (GOO), four of whom underwent repeated sequential balloon dilations and/or needle-knife incisions with steroid injection for alleviation of GOO. The other 29 patients were incidentally found to have a non-obstructing GAW. Age at diagnosis ranged from 30-87 years. Non-obstructing GAWs are mostly incidental findings. The most frequently observed symptom prompting endoscopic work-up was refractory gastroesophageal reflux (n = 24, 70.6%) followed by abdominal pain (n = 11, 33.4%), nausea and vomiting (n = 9, 26.5%), dysphagia (n = 6, 17.6%), unexplained weight loss, (n = 4, 11.8%), early satiety (n = 4, 11.8%), and melena of unclear etiology (n = 3, 8.82%). Four of five GOO patients were treated with balloon dilation (n = 4), four-quadrant needle-knife incision (n = 3), and triamcinolone injection (n = 2). Three of these patients required repeat intervention. One patient had a significant complication of perforation after needle-knife incision.

Endoscopic intervention for GAW using balloon dilation or needle-knife incision is generally safe and effective in relieving symptoms, however repeat treatment may be needed and a risk of perforation exists with thermal therapies.

Core tip: Gastric antral webs (GAWs) in adults are rare, likely often overlooked, and when seen, considered to be incidental findings on upper endoscopy. They can, however, cause symptoms including gastric outlet obstruction. Herein, we review management of 34 such patients that underwent treatment at our tertiary institution. Our findings indicate that GAWs can be managed safely and effectively via endoscopic intervention with balloon dilation and endoscopic incision with needle knife, although repeat procedures were required in some cases, and a small risk of perforation exists. Standards for appropriate surveillance and appropriate indications for surgical intervention are yet to be defined.

- Citation: Morales SJ, Nigam N, Chalhoub WM, Abdelaziz DI, Lewis JH, Benjamin SB. Gastric antral webs in adults: A case series characterizing their clinical presentation and management in the modern endoscopic era. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2017; 9(1): 19-25

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v9/i1/19.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v9.i1.19

Gastric antral web (GAW), or antral diaphragm, is an uncommon endoscopic finding and a rare cause of gastric outlet obstruction (GOO). Evans and Sarani define GAW as a layer of submucosa and that runs perpendicular to the axis of the stomach[1]. The diagnosis of GAW is suspected during esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) if aperture size of the antrum does not vary with peristalsis and is confirmed by demonstrating a normal pylorus distal to the GAW. To date, the majority of cases have been reported in the pediatric population ranging from premature neonates to teenagers[2-4]. The first case in an adult patient was reported by Sames et al in 1949, and very few have been described in the last thirty years[5]. Thus, the clinical setting in which GAW is likely to arise, as well as the optimal endoscopic and/or surgical interventions are poorly defined.

The differential diagnosis of a GAW is broad and includes “distal gastrospasm”, redundant gastric mucosa, hypertrophic gastric rugae, heterotrophic pancreatic tissue and cholecystogastrocolic bands and perigastric adhesions[6,7]. Historically, upper gastrointestinal (UGI) series were the imaging modality of choice for patients suspected of having GAW or other obstructive pathology. Interestingly, the radiographic incidence of GAW far exceeds that reported in medical and surgical literature with almost half the cases being incidental findings in “asymptomatic” individuals[8]. The characteristic radiographic findings are thin, knife-like linear septae 2-3 mm thick seen as radiolucent lines 1-2 cm proximal to the pylorus projecting from the greater and lesser curvature[6]. The antrum distal to the web may fill giving the appearance of a “double duodenal bulb”, and contrast exiting through the central orifice gives a “jet effect”[7]. However, a GAW may easily be confused with the pylorus despite the use of double-contrast radiographs, and it is recommended that right anterior oblique and left posterior oblique views be obtained[7]. A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan may demonstrate the cutoff proximal to the pylorus and a normal caliber pylorus and duodenum downstream with greater accuracy. Rarely has a duodenal web been described[9].

In adults, patients with GAW often develop symptoms when the aperture size is less than 1 centimeter in diameter[10]. Symptoms are usually worse post-prandially and include water brash, dysphagia, odynophagia, abdominal distention, nausea, forced or spontaneous vomiting, early satiety, weight loss, epigastric or right upper quadrant abdominal pain, anterior chest pain and non-bloody, watery diarrhea[5,9,11,12]. Historically, most cases are diagnosed during an endoscopic or radiographic work-up to explain various upper gastrointestinal symptoms[1,13].

We evaluated patients with a diagnosis of GAW by EGD performed at Medstar Georgetown University Hospital between 2007 and 2013. In all cases, the diagnosis of GAW was suspected during EGD if aperture size of the antrum does not vary with peristalsis or if a “double bulb” sign is present on upper gastrointestinal (UGI) series. Confirmation of the diagnosis was made by demonstrating a normal pylorus distal to the GAW.

For all patients, data were collected retrospectively, including demographic data, presenting symptoms, imaging prior to EGD, endoscopic findings, endoscopic interventions, and course following index EGD. These data were gathered via a review of procedure reports and other materials found in our electronic medical records systems.

Univariate analyses were conducted to describe the distributions of demographic data, presenting symptoms and need for intervention. Significance statements refer to P values of two-tailed tests that were < 0.05.

We identified 34 cases of GAW encountered among 24640 EGDs performed at our institution from 2007-2013 for an incidence of 0.14%. These cases included five instances in which GAW was complicated by GOO as described below. There were no significant differences in presenting symptoms between patients with GAW with GOO and non-obstructing GAW.

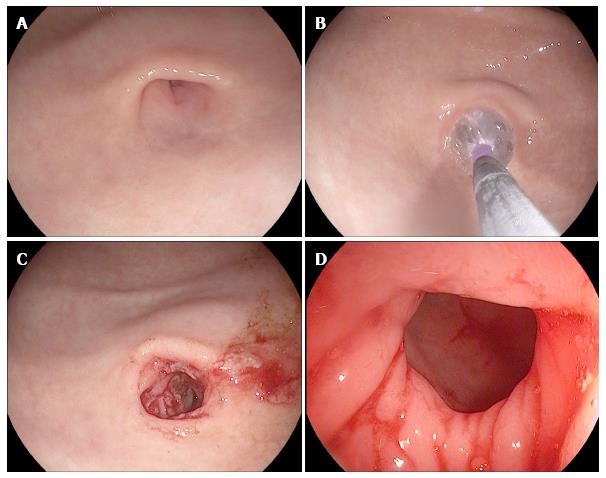

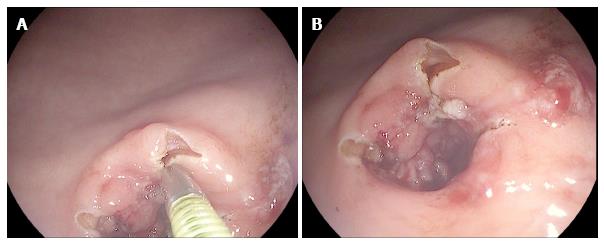

A 60-year-old Caucasian female with hypothyroidism, hyperlipidemia, and functional constipation was evaluated for a three-month history of gastroesophageal reflux. She had been experiencing odynophagia and retrosternal pressure after eating solid foods. Her symptoms were not alleviated with omeprazole, cimetidine, or bismuth subsalicylate. Laboratory testing, including thyroid function tests, were normal. EGD revealed retained food in the stomach and an obstructing antral web (Figure 1A). Balloon dilation to 12 mmHg was performed (Figure 1B and C), allowing visualization of a normal pylorus beyond the narrowing (Figure 1D). Following balloon dilation, needle-knife cuts were made in four quadrants (Figure 2) and 80 mg triamcinolone was injected. The patient remained asymptomatic for five years, at which time symptoms similar to those at initial presentation returned. She underwent a repeat EGD which showed recurrence of the obstructing antral web. The GAW was sequentially balloon dilated to 15 mmHg, followed by repeat four quadrant needle-knife cuts and reinjection of 80 mg triamcinolone. The patient remained asymptomatic for two years at which time EGD showed a third recurrence of the GAW, requiring repeat balloon dilation, four-quadrant needle-knife cuts, and triamcinolone injection. Although her symptoms were alleviated, the patient was advised to seek surgical evaluation for more permanent intervention, should her symptoms recur.

A 80-year-old African-American female with hypertension, emphysema and prior breast and lung cancer presented with dysphagia to solids and liquids, persistent nausea and vomiting, and abdominal fullness. CT scan showed a partial GOO without evidence of external compression or intrinsic mass at the pylorus, while UGI series suggested a near complete gastric outlet obstruction. EGD revealed retained food in the body and antrum of the stomach, severe antral erosions, and an obstructing GAW. Sequential balloon dilation to 10 mmHg was performed, allowing the regular 9.8 mm endoscope to be advanced without resistance. Given the partial return of symptoms within two weeks, EGD was repeated, and the GAW was incised using needle-knife cautery. Subsequently, the patient noted alleviation in her symptoms, and during follow-up EGD a week later, the endoscope traversed the antral web with minimal resistance.

A 68-year-old Hispanic male with diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, and chronic kidney disease was evaluated for a ten-year history of nausea, frequent regurgitation and early satiety with a 90 pound weight. Screening colonoscopy two years prior was unremarkable, as was an UGI series and CT scan of the abdomen. EGD at the time showed antral narrowing, complicated by post biopsy bleeding. After a two year course of esomeprazole, repeat EGD showed retained gastric contents and an obstructing GAW with 6 mm aperture. Balloon dilation to 15 mm was performed, allowing a 9 mm endoscope to be advanced. The patient was seen in our clinic three weeks later and reported a five pound weight gain in the interim with no recurrence of his symptoms.

A 74-year-old Caucasian female with hypertension, arthritis and gastroesophageal reflux disease was admitted to the inpatient service for a six-week history of abdominal cramping and diarrhea with intermittent melena. She reported no fever, nausea, vomiting, early satiety, weight loss, recent travel, or recent antibiotic use. Stool studies were unremarkable for enteric pathogens or fecal leukocytes. CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed pancolitis and a thickened antrum. The patient was empirically started on budesonide and the frequency of her bowel movements decreased. A colonoscopy performed three weeks later was unremarkable, and biopsies were negative for inflammatory bowel disease or microscopic colitis suggesting a possible transient infectious or ischemic colitis. EGD performed at the same time showed an obstructing GAW, but no intervention was performed given the lack of symptoms suggesting GOO. Of note, an EGD performed five years earlier showed a gastric ulcer, but a GAW was not described. The patient’s symptoms continued to improve over the next several weeks.

An 81-year-old Caucasian woman with scleroderma and gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) treated previously with argon plasma coagulation presented with persistent nausea and vomiting. A GAW causing GOO had been identified at an outside institution, and she was referred for endoscopic management. Upon our initial EGD, the patient was treated with needle-knife incision and injection of 80 mg of triamcinolone. Following this procedure, her symptoms improved, but did not resolve, and she returned for further endoscopic management 8 wk later. At that time, we again performed needle-knife incision, however a complication of perforation was noted with direct visualization of small bowel through the gastric defect. Three endoscopic clips were placed to close the defect, but CT of the abdomen revealed a large pneumoperitoneum. The patient was then taken emergently to the operating room, where a 1.5 cm perforation in the distal aspect of the lesser curvature of the stomach was identified laparoscopically and closed with full-thickness surgical sutures. On post-operative day five, the patient underwent an UGI series that revealed no evidence of persistent perforation and only mild narrowing in the gastric antrum. She was discharged home the following day, and upon follow-up in clinic reported that she was no longer experiencing her symptoms of GOO.

Among the 34 cases of GAW, 19 (55.9%) occurred in women and 15 (44.1%) in men. Ages at the time of diagnosis ranged from 30 to 87 years (mean 65.3, St.dev 12.9). Five patients had an obstructing GAW (14.7%, discussed above) and 29 patients were incidentally found to a have non-obstructing GAW (85.3%). The most frequently reported symptom was chronic gastroesophageal reflux in 24 patients (70.6%), each of whom had taken proton-pump inhibitor therapy for various periods without significant improvement. Nine patients complained of diffuse abdominal pain (26.5%), one of epigastric pain (2.94%), and one of substernal discomfort (2.94%). Eight patients reported nausea and vomiting (23.5%). Six patients had dysphagia to solids (17.6%) and one to solids and liquids (2.9%). Four patients complained of early satiety (11.8%), three of whom also experienced weight loss (Table 1).

| Patient No. | Age | Sex | Year of diagnosis | Obstructing GAW | Reflux symptoms | PPI course | Dysphagia | Nausea/vomiting | Abdominal discomfort | Weight loss |

| 11 | 60 | F | 2006 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Solid | Yes | No | No |

| 21 | 80 | F | 2008 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Solid/liquid | Yes | No | No |

| 31 | 68 | M | 2013 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| 4 | 74 | F | 2011 | Yes | No | No | No | No | Diffuse | No |

| 51 | 81 | F | 2015 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| 6 | 85 | F | 2003 | No | No | No | No | No | Diffuse | No |

| 7 | 62 | F | 2003 | No | No | No | No | No | Diffuse | No |

| 8 | 56 | M | 2003 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 9 | 38 | M | 2004 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 10 | 49 | M | 2004 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 11 | 68 | M | 2004 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 12 | 53 | M | 2004 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 13 | 61 | F | 2005 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 14 | 67 | M | 2006 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| 15 | 69 | M | 2006 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 16 | 82 | M | 2007 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 17 | 63 | F | 2007 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 18 | 66 | F | 2007 | No | No | No | No | Yes | Diffuse | Yes |

| 19 | 54 | F | 2007 | No | Yes | Yes | Solid | No | Substernal | No |

| 20 | 76 | F | 2007 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 21 | 58 | F | 2007 | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| 22 | 70 | F | 2009 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Diffuse | No |

| 23 | 67 | F | 2009 | No | No | No | No | No | Diffuse | No |

| 24 | 56 | F | 2010 | No | No | No | No | No | Diffuse | No |

| 25 | 30 | F | 2010 | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| 26 | 57 | M | 2011 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 27 | 73 | M | 2011 | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| 28 | 52 | F | 2011 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 29 | 71 | M | 2011 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Diffuse | No |

| 30 | 67 | M | 2012 | No | Yes | Yes | Solid | No | Epigastric | No |

| 31 | 68 | F | 2012 | No | Yes | Yes | Solid | No | No | No |

| 32 | 66 | M | 2013 | No | No | No | No | Yes | Diffuse | No |

| 33 | 87 | F | 2013 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 34 | 86 | M | 2014 | No | No | Yes | Solid | No | No | No |

Among patients undergoing further work-up for their chronic gastroesophageal reflux, eight of 24 were found to have a hiatal hernia on endoscopy (33.3%), four had duodenal ulcers (18.2%), one had an antral ulcer (4.17%), and one had a Schatzki ring in addition to the GAW (4.17%). Of note, eight of the 34 patients in this series had prior endoscopies performed three to 14 years prior without description of a GAW (23.5%).

While the cause of GAW in adults is poorly understood, in 1965 Rhind et al[12] theorized that GAW was “acquired” in adults, and resulted from scarring as circumferential pyloric and pre-pyloric peptic ulcers heal. This theory fits well with our Case 5 where GAW was likely the result of antral scarring from prior APC treatment of GAVE. Given the higher reported incidence in children, many authors believed the “congenital” theory that rapid proliferation of epithelial cells in the gut lumen was not followed by vacuole formation, fusion and recanalization during early development[11,14]. It was further speculated in the past that a congenital GAW may manifest only in adulthood as a result of a decline in efficacy of mastication from fewer teeth, dentures, or diminished muscle strength, or, alternatively, from hypertrophy and decompensation of the stomach chronically forcing food through a narrowed opening, although to our knowledge, these theories were never validated[5,6,14].

Given the prevalence of chronic gastroesophageal reflux in this cohort, we believe the association between this acidity and GAW may be significant. Two-thirds of our patients had reflux symptoms, five of whom had duodenal or gastric ulcers visualized during endoscopy. This is similar to historical reports of GAWs in three adult patients with gastric ulcer of the lesser curvature, and three others who had a duodenal ulcer[5,7,12]. Eight of our patients had prior endoscopies in which a GAW was not described, and while this might argue against the notion that GAW is a congenital anomaly, it is equally possible that the web simply may have been missed, as they can easily be overlooked or confused with other entities.

In our patients, GAW was identified on EGD and fulfilled the criteria set forth by Sokol et al[15] in 1965: fixed size aperture or “pseudopylorus”; smooth GAW mucosa devoid of folds; and normal peristalsis to the GAW that stops abruptly but continues beyond in a concordant fashion. Evidence of gastric retention was seen in 14.7% of the patients in our series, further confirming the clinical picture.

Conservative management with acid suppression, such as proton-pump inhibitors, has been reported to provide temporary relief, but does not result in a permanent cure. Most of the published literature describing GAW dates back 30-40 years and predates modern endoscopic approaches to treatment. Following preliminary exploratory laparotomy or duodenotomy, an incision of the GAW to the central aperture; enlargement of the aperture via lysis with transverse gastroplasty or pyloroplasty; or a finger fracture of the GAW and pyloromyotomy were the most common surgical procedures utilized[11]. Although such surgery successfully restored a functional gastric outlet and alleviated symptoms, an endoscopic “webotomy”, first suggested by Swartz and Shepard in 1956, heralded the minimally invasive options currently deemed safe given the lack of a muscularis propia in GAWs, and a low risk of perforation[14]. Endoscopic balloon dilation to 10 mm was first described in 1984, and has proven to be effective and safe to repeat[10,16]. However, frequent recurrence led to the development of more permanent interventions. Endoscopic snaring was used successfully in treating an obstructing GAW in an infant[9], and three radial incisions with a papillotome relieved symptoms from a partially obstructing GAW in a 14-year-old female[17]. In 1988, Al-Kawas reported the use of Nd:YAG laser therapy in a 64-year-old symptomatic woman with an obstructing GAW to create a 14 mm lumen, which alleviated symptoms in 48 h, although she later required surgery[9]. This technique has also proven effective in treating an obstructing duodenal web[9]. In 2013, Salah reported a case of obstructing GAW in an 11 year old boy treated with snare resection, electroincision and balloon dilation[18]. Several cases, including ours, have shown long-term resolution of symptoms after radial incisions using needle-knife electrocautery, but the use of empiric triamcinolone acetate for its anti-inflammatory effects has not been previously reported. However, we believe that a combination of balloon dilation and/or needle knife incisions remain the primary endoscopic management tools with low risk of perforation or significant bleeding. In our series, perforation following needle-knife incision occurred in one patient who was likely predisposed by antral scarring from prio APC treatment. In our practice, interventions were only performed after biopsies had confirmed the absence of malignancy. In addition, interventions were only performed in patients with clinically significant symptoms of GOO that were refractory to medical management. The role of surgical intervention for adults with GAWs refractory to endoscopic treatment remains incompletely defined in the endoscopic era.

In conclusion, GAW is a rare endoscopic finding among adults undergoing endoscopy (0.14% in this series over a 7 year period). It is likely often overlooked and is considered an incidental finding when seen, but may be associated with GOO, refractory GERD or gastric or duodenal ulceration. Through-the-scope balloon dilation with or without a needle-knife incision of the web appears to be effective in many patients, although the need for repeat endoscopic treatment was frequent among those with high-grade GOO. The current role for surgical intervention remains to be defined, as it appears to be less necessary in adults than in the past.

Gastric antral webs (GAWs) are rare entities in adults which can cause gastric outlet obstruction (GOO). In the endoscopic era, interventional endoscopic techniques have been employed in the management of these patients.

Optimal technique and devices for intervention on GAWs with GOO have yet to be defined, however several techniques have been described in the literature.

Herein, the authors report their experience with GAWs at the tertiary institution. The authors found that endoscopic intervention for GAW using balloon dilation or needle-knife incision is generally safe and effective, however repeat treatment may be required and a risk of perforation exists with thermal therapies.

These techniques, including needle-knife incision, balloon dilation, and triamcinolone injection are generally safe and effective endoscopic interventions, however repeat treatment may be needed and a risk of perforation exists with thermal therapies. These treatment modalities can be used to treat gastric antral webs associated with gastric outlet obstruction.

It’s a quite extensive manuscript especially for a case series.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Garg P, Tomizawa M S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Evans SR, Sarani B. Anatomic Variants of the Stomach: Diaphragmatic Hernia, Volvulus, Diverticula, Heterotopia, Antral Web, Duplication Cysts, and Microgastria. Gastrointestinal Disease: An Endoscopic Approach. Thorofare, NJ: Slack Incorporated 2002; 530-531. |

| 2. | Lui KW, Wong HF, Wan YL, Hung CF, Ng KK, Tseng JH. Antral web--a rare cause of vomiting in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2000;16:424-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bell MJ, Ternberg JL, Keating JP, Moedjona S, McAlister W, Shackelford GD. Prepyloric gastric antral web: a puzzling epidemic. J Pediatr Surg. 1978;13:307-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Godambe SV, Boriana P, Ein SH, Shah V. An asymptomatic presentation of gastric outlet obstruction secondary to congenital antral web in an extremely preterm infant. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sames CP. A case of partial atresia of the pyloric antrum due to a mucosal diaphragm of doubtful origin. Br J Surg. 1949;37:244-246, illust. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Feliciano DV, van Heerden JA. Pyloric antral mucosal webs. Mayo Clin Proc. 1977;52:650-653. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Ghahremani GG. Nonobstructive mucosal diaphragms or rings of the gastric antrum in adults. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1974;121:236-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Pederson WC, Sirinek KR, Schwesinger WH, Levine BA. Gastric outlet obstruction secondary to antral mucosal diaphragm. Dig Dis Sci. 1984;29:86-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Al-Kawas FH. Endoscopic laser treatment of an obstructing antral web. Gastrointest Endosc. 1988;34:349-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bjorgvinsson E, Rudzki C, Lewicki AM. Antral web. Am J Gastroenterol. 1984;79:663-665. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Hait G, Esselstyn CB, Rankin GB. Prepyloric mucosal diaphragm (antral web): report of a case and review of the literature. Arch Surg. 1972;105:486-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rhind JA. Mucosal stenosis of the pylorus. Br J Surg. 1959;46:534-540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Banks PA, Waye JD. The gastroscopic appearance of antral web. Gastrointest Endosc. 1969;15:228-229. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Swartz WT, Shepard RD. Congenital mucosal diaphragm of the pyloric antrum. J Ky State Med Assoc. 1956;54:149-151. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Sokol EM, Shorofsky MA, Werther JL. Mucosal diaphragm of the gastric antrum. Gastrointest Endosc. 1965;12:20-21 passim. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Gul W, Abbass K, Markert RJ, Barde CJ. Gastric antral web in a 103-year-old patient. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2011;2011:957060. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Berr F, Rienmueller R, Sauerbruch T. Successful endoscopic transection of a partially obstructing antral diaphragm. Gastroenterology. 1985;89:1147-1151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Salah W, Baron TH. Gastric antral web: a rare cause of gastric outlet obstruction treated with endoscopic therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |