Published online Apr 10, 2016. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v8.i7.349

Peer-review started: October 30, 2015

First decision: December 11, 2015

Revised: December 27, 2015

Accepted: January 29, 2016

Article in press: January 31, 2016

Published online: April 10, 2016

Processing time: 158 Days and 14.7 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the risk factors for postoperative bleeding after gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) based on the latest guidelines.

METHODS: A total of 262 gastric neoplasms were treated by ESD at our center during a 2-year period from October 2012. We analyzed the data of these cases retrospectively to identify the risk factors for post-ESD bleeding.

RESULTS: Of the 48 (18.3%) cases on antithrombotic treatment, 10 were still receiving antiplatelet drugs perioperatively, 13 were on heparin replacement after oral anticoagulant withdrawal, and the antithrombotic therapy was discontinued perioperatively in 25 cases. Postoperative bleeding occurred in 23 cases (8.8%). The postoperative bleeding rate in the heparin replacement group was 61.5%, significantly higher than that in the non-antithrombotic therapy group (6.1%). Univariate analysis identified history of antithrombotic drug use, heparin replacement, hemodialysis, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, elevated prothrombin time-international normalized ratio, and low hemoglobin level on admission as risk factors for post ESD bleeding. Multivariate analysis identified only heparin replacement (OR = 13.7, 95%CI: 1.2-151.3, P = 0.0329) as a significant risk factor for post-ESD bleeding.

CONCLUSION: Continued administration of antiplatelet agents, based on the guidelines, was not a risk factor for postoperative bleeding after gastric ESD; however, heparin replacement, which is recommended after withdrawal of oral anticoagulants, was identified as a significant risk factor.

Core tip: There are few data on the risk factors for postoperative bleeding after gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) in patients continued on antithrombotic treatment during the perioperative period. This study was aimed to evaluate the risk factors for postoperative bleeding after gastric ESD in patients continued or not continued on antithrombotic treatment. Univariate analysis showed that an antithrombotic agent user, especially heparin replacement was significantly associated with risk factors for postoperative bleeding. Multivariate analysis identified heparin replacement as the independent risk factor for post ESD bleeding. Therefore, patients with heparin replacement should be carefully observed after gastric ESD.

- Citation: Shindo Y, Matsumoto S, Miyatani H, Yoshida Y, Mashima H. Risk factors for postoperative bleeding after gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection in patients under antithrombotics. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2016; 8(7): 349-356

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v8/i7/349.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v8.i7.349

Early gastric cancer is defined as a tumor confined to the mucosa or submucosa, irrespective of the presence/absence of lymph node metastasis[1]. Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is a widely used procedure now for early gastric cancers and gastric adenomas[2,3]. The major complications of this procedure are perforation and postoperative bleeding. Postoperative bleeding after gastric ESD is reported to occur in 4.8%-9.4% of patients not receiving antithrombotic agents/patients in whom these drugs are discontinued during the perioperative period[4-9]. While several factors (large resected tumor size[6,8], advanced age of the patient, long procedure time[10,11], patient under dialysis, and ulcerative lesions[12,13]) have been suggested as risk factors for postoperative bleeding after gastric ESD, no consensus has been reached yet with regard to the precise risk factors for postoperative bleeding after gastric ESD.

Recently, the incidence of gastric cancer has been increasing, owing to the increasing lifespan of the general population[14]. The number of patients suffering from gastric cancer and taking antithrombotic agents is also growing as a result of the increasing prevalence of ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, and other arteriosclerotic diseases. The previous guidelines published by the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society (JGES) focused primarily on the prevention of hemorrhage after gastrointestinal endoscopy associated with continuation of antithrombotic therapy in the perioperative period, without considering the risk of thrombosis associated with withdrawal of the therapy[15]. The new edition of the JGES guidelines for gastroenterological endoscopy in patients undergoing antithrombotic treatment was published in July 2012. The new guidelines include discussions of the risk of gastroenterological hemorrhage associated with continuation of antithrombotic therapy, as well as of the risk of thromboembolism associated with discontinuation of antithrombotic therapy[16]. There are few data on the risk factors for postoperative bleeding after gastric ESD in patients continued on antithrombotic treatment during the perioperative period.

We have been performing ESD for gastric neoplasms based on the new guidelines since October 2012. This study was aimed at evaluating the risk factors for postoperative bleeding after gastric ESD in patients continued or not continued on antithrombotic treatment.

The subjects were 283 cases who underwent ESD for gastric neoplasms at Saitama Medical Center from October 2012 to September 2014. Of these cases, 21 cases were excluded from this retrospective study for the following reasons: Multiple lesions were removed on the same day (19 cases), and the procedure could not be completed (2 cases).

We retrospectively reviewed the patient’s medical records and collected the following data: Age, sex, hemoglobin level, prothrombin time-international normalized ratio (PT-INR), comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, hemodialysis, or liver cirrhosis), the Charlson comorbidity index[17,18], and details about any antithrombotic therapy. Patients taking antithrombotic agents were classified into three groups based on the guidelines: A group in which the antithrombotic therapy was discontinued, a group in which antiplatelet drug therapy was continued (including replacement of thienopyridine with aspirin or cilostazol)[16], and a group in which oral anticoagulant treatment was replaced by heparin. We used continuous infusion of unfractionated heparin for heparin replacement. The start dose of unfractionated heparin was 10000 to 15000 units. Check activated partial thromboplastin time during continuous infusion; adjust to target of 1.5 to 2 times the upper limit of control. We stopped continuous heparin infusion four to six hours before procedure.

ESD was performed using the conventional single-channel endoscope (GIF-Q260J, or -H260Z; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and a high-frequency electrical generator (VIO 300D; Erbe, Tubingen, Germany) by 15 endoscopists. An expert endoscopist was defined as one who had the experience of performing more than 50 gastric ESDs. After marking dots circumferentially on the surrounding normal mucosa 5-10 mm away from the lesion demarcation line, a mixture of 10% glycerin and 0.4% sodium hyaluronate solution (Mucoup; Johnson and Johnson, Tokyo, Japan) containing indigo carmine and 0.01% epinephrine was injected submucosally. A circumferential incision was performed using the Dual knife (KD-650L; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) or Flush knife (DK2618JN20; Fujinon, Tokyo, Japan). After the circumferential incision was completed, the submucosa was dissected using the Dual knife, Flush knife, or IT2 knife (KD-611L; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Hemostatic forceps (FD-410LR; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) were used to control the bleeding during and after the procedure. A second-look endoscopy was performed routinely the following weekday, and preventive coagulation of visible vessels was performed[19]. A proton pump inhibitor, that is, omeprazole 20 mg, was administrated intravenously twice a day starting on the day of the ESD until the day before the start of a soft diet. Then, oral administration of esomeprazole 20 mg was started and continued for 8 wk after the ESD.

All lesions were pathologically examined on the basis of the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma[1]. The macroscopic type was classified as the protruded type, flat type, or depressed type. The size of the tumor and the resected area were measured on the specimen. The location of the tumor was classified as the upper third, middle third, or lower third of the stomach. The depth of the tumor invasion was classified as pT1a (up to the mucosa) or pT1b (up to the submucosa). Invasion of the submucosal layer (SM) was divided into SM1 (less than 0.5 mm from the muscularis mucosae) and SM2 (more than 0.5 mm submucosal invasion). The tumor differentiation grade was based on the most dominant differentiation grade, and the tumors were classified as adenoma, differentiated cancer (including well- differentiated, moderately differentiated, tubular, and papillary adenocarcinoma), or undifferentiated cancer (poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma and signet-ring cell carcinoma).

En bloc resection was defined as resection in a single piece. Complete resection was defined as en bloc resection of a tumor with a negative horizontal margin and vertical margin. Curative resection was defined as follows: En bloc resection, tumor size ≤ 2 cm, differentiated-type tumor, pT1a, ulceration (Ul)-negative, no lymphovascular infiltration [ly(-), v(-)], negative horizontal margin (HM0), and negative vertical margin (VM0). The expanded indications of curative resection were as follows: En bloc resection, ly(-), v(-), HM0, and VM0, as well as: (1) tumor size ≥ 2 cm, differentiated-type tumor, pT1a, Ul(-); (2) tumor size ≤ 3 cm, differentiated-type tumor, pT1a, Ul(+); (3) tumor size ≤ 2 cm, undifferentiated-type tumor, pT1a, Ul(-); and (4) tumor size ≤ 3 cm, differentiated-type tumor, pT1b (SM1)[20,21]. All other lesions were classified as non-curative resection.

Postoperative bleeding was defined as bleeding events, including hematemesis and/or melena, after the procedure requiring endoscopic hemostasis, or a decrease of the hemoglobin level by more than 2 mg/dL as compared to the preoperative hemoglobin level.

Data are expressed as mean ± SD or as percentages. Statistical analysis was carried out using student’s t-test or Fisher’s exact test. Factors identified as significant by the univariate analysis (P < 0.15) were entered into a multivariate logistic regression analysis model. All data analyses were carried out using the StatView software (version 5.0; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, United States). Differences with P values of less than 0.05 were considered as denoting significance. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Dr. Satohiro Matsumoto from the Department of Gastroenterology, Jichi Medical University, Saitama Medical Center, Saitama, Japan.

The overall clinicopathological profiles of the 262 gastric neoplasms in 250 patients are shown in Table 1. Twelve patients had received treatment for 2 lesions occurring metachronously during the investigation period, and were counted twice. The mean age of the patients was 71 ± 8 years (range 32-87) (M:F = 190:72). Of the 262 cases, 48 (18.3%) had a history of receiving antithrombotic therapy for cardiovascular diseases. The details of the antithrombotic therapy were as follows: Aspirin 28 cases, clopidogrel 6 cases, ticlopidine 1 case, cilostazol 4 cases, and warfarin 14 cases. Perioperative management of the antithrombotic therapy was as follows: The antithrombotic drugs were discontinued in 25 cases, the antiplatelet agents were continued in 10 cases, and oral anticoagulant treatment was replaced by heparin in 13 cases (most of the patients who were under warfarin treatment received heparin replacement, except one patient who had past history of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation).

| Patients background factors | |

| Age (yr, mean ± SD) (range) | 71 ± 8 (32-87) |

| Sex (male/female) | 190/72 |

| Antithrombotic agent user | 48 (18.3%) |

| Detail | |

| Aspirin | 28 |

| Clopidogrel | 6 |

| Ticlopidine | 1 |

| Cilostazol | 4 |

| Warfarin | 14 |

| Heparin replacement (withdrawal warfarin) | 13 |

| Hemodialysis | 6 (2.3%) |

| Hypertension | 130 (49.6%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 54 (20.6%) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 48 (18.3%) |

| Resected lesion factors | |

| Curability (curative/expanding indications curative/non-curative) | 175/57/30 |

| Macroscopic type (depressed/flat/protruded) | 151/101/10 |

| Location (upper third/middle third/lower third) | 38/73/151 |

| Circumference (anterior wall, greater curvature, lesser curvature, posterior wall) | 38/52/124/48 |

| Tumor size (mm, mean ± SD) (range) | 15.9 ± 10.9 (2-85) |

| Differentiation (adenoma/differentiated cancer/undifferentiated cancer) | 34/216/12 |

| Depth (M:SM1:SM2) | 236/12/14 |

| Ulcer findings positive | 16 (6.1%) |

| Lymphovascular infiltration positive | 18 (6.9%) |

| Horizontal or vertical margin positive | 8 (3.1%) |

| Perioperative factors | |

| En bloc resection | 259 (98.8%) |

| Operator (beginner/expert) | 97/165 |

| Operation time (min, mean ± SD) (range) | 81.5 ± 50.9 (16-307) |

| Resected size (mm, mean ± SD) (range) | 36.1 ± 11.6 (12-88) |

| Perforation | 2 (0.8%) |

| Postoperative bleeding | 23 (8.8%) |

| Blood transfusion (%) | 7 (2.7%) |

The mean tumor size was 15.9 ± 10.9 mm (range, 2-85 mm). The gastric tumors were mainly located in the lower third and in the lesser curvature of the stomach. The en bloc resection rate was 98.8% (259 cases) and the curative resection rate was 66.8% (175 cases). The curative resection rate according to the expanded indications was 21.8% (57 cases). The non-curative resection rate was 11.5% (30 cases). Postoperative bleeding occurred in 23 cases (8.8%). Perforation during ESD occurred in 2 cases. No events of thromboembolism occurred with discontinuation of the antithrombotic therapy. Among the 23 patients who had postoperative bleeding, 6 (26.1%) needed blood transfusion. One patient needed blood transfusion due to underlying anemic disease.

Univariate analysis carried out to determine the risk factors for postoperative bleeding identified antithrombotic agent user (P = 0.0011), heparin replacement (P < 0.0001), hemodialysis (P = 0.0321), diabetes mellitus (P = 0.0435), cardiovascular disease (P = 0.0069), PT-INR (P < 0.0001), and the hemoglobin level on admission (P < 0.0153) as risk factors for postoperative bleeding (Table 2).

| Present (n = 23) | Absent (n = 239) | P value | |

| Patients background factors | |||

| Age (yr, mean ± SD) (range) | 73 ± 7 (58-82) | 71 ± 8 (32-87) | 0.4304 |

| Sex (male/female) | 7/16 | 174/65 | 0.7397 |

| Antithrombotic agent user | 10 (43.5%) | 38 (15.9%) | 0.00111 |

| Category of antithrombotic treatment (non-antithrombotic therapy/discontinuation of antithrombotic agents/continuation of antiplatelet agents/heparin replacement) | 13/0/2/8 | 201/25/8/5 | < 0.00011 |

| Hemodialysis | 2 (8.7%) | 4 (1.7%) | 0.03211 |

| Hypertension | 10 (43.5%) | 120 (50.2%) | 0.5375 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1 (4.3%) | 53 (22.1%) | 0.04351 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 9 (39.1%) | 39 (16.3%) | 0.00691 |

| PT-INR (mean ± SD) (range) | 1.2 ± 0.5 (0.9-2.1) | 0.9 ± 0.1 (0.9-2.0) | < 0.00011 |

| Charlson comorbidity index (mean ± SD) (range) | 3.5 ± 1.2 (1-6) | 3.2 ± 1.3 (0-8) | 0.2674 |

| Hemoglobin levels on admission (g/dL, mean ± SD) (range) | 12.5 ± 1.3 (9.6-14.4) | 13.3 ± 1.5 (7.8-17.1) | 0.01531 |

| Resected lesion factors | |||

| Curability (curative/expanding indications curative/non-curative) | 19/3/1 | 156/54/29 | 0.2305 |

| Macroscopic type (depressed/flat/protruded) | 11/11/1 | 140/90/9 | 0.6058 |

| Location (upper third/middle third/lower third) | 2/3/18 | 36/70/133 | 0.0907 |

| Circumference (anterior wall, greater curvature, lesser curvature, posterior wall) | 3/4/11/5 | 35/48/113/43 | 0.9645 |

| Tumor size (≥ 21 mm) | 3 (13.0%) | 51 (21.3%) | 0.3476 |

| Differentiation (adenoma/differentiated cancer/undifferentiated cancer) | 3/2/18 | 31/198/10 | 0.6108 |

| Depth (M:SM1:SM2) | 22/0/1 | 214/12/13 | 0.525 |

| Ulcer findings positive | 0 (0%) | 16 (6.7%) | 0.2003 |

| Lymphovascular infiltration positive | 1 (4.3%) | 17 (7.1%) | 0.6166 |

| Horizontal or vertical margin positive | 1 (4.3%) | 7 (2.9%) | 0.7204 |

| Tumor size (mm, mean ± SD) | 17.3 ± 16.1 (6-85) | 15.7 ± 10.3 (2-70) | 0.5147 |

| Perioperative factors | |||

| Operator (beginner/expert) | 9/14 | 88/151 | 0.8265 |

| Resected size (mm, mean ± SD) (range) | 38.9 ± 12.8 (25-88) | 35.8 ± 11.5 (12-85) | 0.5147 |

| Perforation (%) | 1 (4.3%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0.1286 |

| Operation time (min, mean ± SD) (range) | 87.4 ± 63.5 (31-260) | 80.9 ± 49.6 (16-307) | 0.5608 |

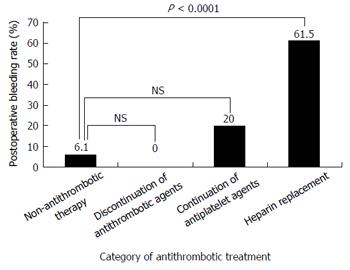

The postoperative bleeding rates in the group in which the antithrombotic therapy was discontinued and the group in which the antiplatelet agents were continued were 0% (0/25) and 20% (2/10), respectively. These rates were not significantly different from the rate in the non-antithrombotic therapy group (6.1%, 13/201). On the other hand, the postoperative bleeding rate in the heparin replacement group was 61.5% (8/13), which was significantly higher than the rate in the non-antithrombotic group (6.1%) (P < 0.0001) (Figure 1).

Multivariate analysis identified heparin replacement (OR = 13.7; 95%CI: 1.2-151.3, P = 0.0329) as the only significant risk factor for post ESD bleeding. It appeared that the tumor location in the lower third of the stomach may be related to postoperative bleeding; however, the difference in the bleeding rate was not statistically significant (OR = 2.9, 95%CI: 0.92-8.94, P = 0.0697) (Table 3).

We investigated risk factors for postoperative bleeding in patients undergoing gastric ESD based on the new guidelines published by the JGES[16]. The postoperative bleeding rate in the group not under anti-thrombotic therapy was 6.1% (13/214), which was consistent with previous reports (4.81%-9.4%)[4-9]. Antithrombotic agents were used in 18.3% of the cases (48/262), and the postoperative bleeding rate increased in the following order, depending on the perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: Group in which the antithrombotic therapy was discontinued (0%, 0/25), group in which antiplatelet agents were continued (20%, 2/10), and the group which received heparin replacement (61.5%, 8/13).

While one previous report suggests that antiplatelet drugs do not increase the risk of postoperative bleeding after ESD[22], there are several reports contending that antiplatelet drugs increase the risk of postoperative bleeding[23-25]. On the other hand, withdrawal of antithrombotic therapy has been reported to increase the risk of development of thromboembolic events[22].

Although there is no mention about ESD, the 2009 guidelines published by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) recommend continuation of aspirin in endoscopy candidates at a high risk of thrombosis. And in patients taking thienopyridines, ASGE recommends substitution of the thienopyridine with aspirin for 7-10 d[26]. The 2011 guidelines of the European Society of gastrointestinal Endoscopy also recommend continuation of aspirin in patients at a high risk of thrombosis. However, the risk of bleeding doubles when the lesions are removed by ESD rather than by endoscopic mucosal resection. Discontinuation of all antiplatelet agents, including aspirin, is recommended, provided that the patient is not at a high risk for thrombotic events[27]. The new JGES guidelines suggest that withdrawal of aspirin monotherapy is not required in patients who would be at a high risk of thromboembolic events following withdrawal of the drug. Aspirin can be withdrawn for 3 to 5 d in patients who are low-risk candidates for thromboembolism. Thienopyridines should be discontinued for 5 to 7 d, and substitution with aspirin or cilostazol should be considered[16]. In our study, the postoperative bleeding rate in the patient group that was continued on antiplatelet drug therapy during the perioperative period was 20%, which is not significantly higher than the reported rate in patients not on antithrombotic drug therapy.

On the other hand, the JGES guidelines recommend heparin replacement after oral anticoagulant agent withdrawal for patients who need to be continued on anticoagulant therapy. Such patients should be treated as high-risk patients, because once thromboembolic complications have occurred, they are often serious[16]. In this study, 13 of the 14 patients who were on oral anticoagulant therapy received heparin replacement. Although the sample size in this study was small, the postoperative bleeding rate in the heparin replacement group was significantly higher (61.3%, 8/13) as compared with that in the patient group not on antithrombotic drug therapy (6.1%, 13/201). Thus, heparin replacement was identified as an independent, significant risk factor for postoperative bleeding after gastric ESD by both univariate analysis and multivariate analysis. Four of the 6 patients who required blood transfusion after gastric ESD were from the heparin replacement group (data not shown). This suggests that heparin replacement is associated with a significant increase in the risk of massive bleeding as compared to the other groups once postoperative bleeding occurred. There are few reports of investigation of the safety of heparin replacement after withdrawal of anticoagulant therapy in patients undergoing gastric ESD; however, all report high postoperative bleeding rates (23.8%-37.5%)[24,28]. In our study, the postoperative bleeding rate was much higher (61.3%, 8/13) than that reported in previous studies. According to Yoshio et al[28] reported that in the heparin replacement group, postoperative bleeding occurred in 2 of 8 cases with tumors in the upper third of the stomach, 5 of 9 cases with tumors in the middle third, and 2 of 7 cases with tumors in the lower third of the stomach. The corresponding values in our study were 2/3, 0/0 and 6/10. Thus, the tumor location might have some influence on the postoperative bleeding rate; however, investigation including a larger number of cases would be required.

Recently, several new oral anticoagulants (NOACs) have been introduced. The NOACs show prompt effects and have shorter half-lives than warfarin[29,30]. Therefore, in patients on anticoagulant therapy scheduled for gastric ESD, it may be better to substitute warfarin with NOACs rather than with heparin. Tsuji et al. reported that use of polyglycolic acid sheets and fibrin glue decreased the risk of bleeding after gastric ESD[31]. This technique, as well as preventive coagulation of visible vessels[19], should be considered to prevent postoperative bleeding in high-risk patients, such as those receiving heparin replacement.

Our investigation had some limitations, as follows: The study was a retrospective study from a single center, and the sample size was small. Detailed prospective investigations are necessary in the future.

In regard to the risks associated with gastric ESD in patients on antithrombotic therapy, continuation of antiplatelet drugs, based on the guidelines, during the perioperative period was not associated with an elevated risk of postoperative bleeding after gastric ESD; the heparin replacement after oral anticoagulant agent withdrawal for patients should be considered carefully for postoperative bleeding after gastric ESD.

The latest guidelines for gastroenterological endoscopy in patients undergoing antithrombotic treatment, published in July 2012 by the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society, include discussions of postoperative bleeding associated with continuation of antithrombotic therapy, as well as of the risk of thromboembolism associated with withdrawal of antithrombotic treatment.

The new guidelines include discussions of the risk of gastroenterological hemorrhage associated with continuation of antithrombotic therapy, as well as of the risk of thromboembolism associated with discontinuation of antithrombotic therapy. There are few data on the risk factors for postoperative bleeding after gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) in patients continued on antithrombotic treatment during the perioperative period.

The postoperative bleeding rate in the heparin replacement group was 61.5%, significantly higher than that in the non-antithrombotic therapy group (6.1%). Multivariate analysis identified only heparin replacement as a significant risk factor for post-ESD bleeding.

The heparin replacement after oral anticoagulant agent withdrawal for patients should be considered carefully for postoperative bleeding after gastric ESD.

Polyglycolic acid is an absorbent suture reinforcement material, which expected for the prevention of post-ESD bleeding in patients with a high risk of bleeding undergoing gastric ESD.

This study was well written and presented. ESD is a novel technique. Endoscopists have to accept the need for advanced endoscopic techniques for performing this technique. Anti-coagulants and anti-platelet agents are widely used to prevent thromboembolic disease.

P- Reviewer: Konigsrainer A, Lee HW, Ozkan OV S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:101-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2390] [Cited by in RCA: 2872] [Article Influence: 205.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Oda I, Saito D, Tada M, Iishi H, Tanabe S, Oyama T, Doi T, Otani Y, Fujisaki J, Ajioka Y. A multicenter retrospective study of endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2006;9:262-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 291] [Cited by in RCA: 314] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Oka S, Tanaka S, Kaneko I, Mouri R, Hirata M, Kawamura T, Yoshihara M, Chayama K. Advantage of endoscopic submucosal dissection compared with EMR for early gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:877-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 487] [Cited by in RCA: 527] [Article Influence: 27.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ono S, Fujishiro M, Niimi K, Goto O, Kodashima S, Yamamichi N, Omata M. Technical feasibility of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer in patients taking anti-coagulants or anti-platelet agents. Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41:725-728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ono S, Kato M, Ono Y, Nakagawa M, Nakagawa S, Shimizu Y, Asaka M. Effects of preoperative administration of omeprazole on bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy. 2009;41:299-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mannen K, Tsunada S, Hara M, Yamaguchi K, Sakata Y, Fujise T, Noda T, Shimoda R, Sakata H, Ogata S. Risk factors for complications of endoscopic submucosal dissection in gastric tumors: analysis of 478 lesions. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:30-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tsuji Y, Ohata K, Ito T, Chiba H, Ohya T, Gunji T, Matsuhashi N. Risk factors for bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric lesions. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:2913-2917. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Okada K, Yamamoto Y, Kasuga A, Omae M, Kubota M, Hirasawa T, Ishiyama A, Chino A, Tsuchida T, Fujisaki J. Risk factors for delayed bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric neoplasm. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:98-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Goto O, Fujishiro M, Oda I, Kakushima N, Yamamoto Y, Tsuji Y, Ohata K, Fujiwara T, Fujiwara J, Ishii N. A multicenter survey of the management after gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection related to postoperative bleeding. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:435-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Toyokawa T, Inaba T, Omote S, Okamoto A, Miyasaka R, Watanabe K, Izumikawa K, Horii J, Fujita I, Ishikawa S. Risk factors for perforation and delayed bleeding associated with endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric neoplasms: analysis of 1123 lesions. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:907-912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Higashiyama M, Oka S, Tanaka S, Sanomura Y, Imagawa H, Shishido T, Yoshida S, Chayama K. Risk factors for bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastric epithelial neoplasm. Dig Endosc. 2011;23:290-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mukai S, Cho S, Kotachi T, Shimizu A, Matuura G, Nonaka M, Hamada T, Hirata K, Nakanishi T. Analysis of delayed bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric epithelial neoplasms. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:875323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Miyahara K, Iwakiri R, Shimoda R, Sakata Y, Fujise T, Shiraishi R, Yamaguchi K, Watanabe A, Yamaguchi D, Higuchi T. Perforation and postoperative bleeding of endoscopic submucosal dissection in gastric tumors: analysis of 1190 lesions in low- and high-volume centers in Saga, Japan. Digestion. 2012;86:273-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Saito H, Osaki T, Murakami D, Sakamoto T, Kanaji S, Tatebe S, Tsujitani S, Ikeguchi M. Effect of age on prognosis in patients with gastric cancer. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76:458-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Committee JGESPE. Guidelines for Gastroenterological Endoscopy version 3. Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society. Tokyo: Igaku Shoin 2006; . |

| 16. | Fujimoto K, Fujishiro M, Kato M, Higuchi K, Iwakiri R, Sakamoto C, Uchiyama S, Kashiwagi A, Ogawa H, Murakami K. Guidelines for gastroenterological endoscopy in patients undergoing antithrombotic treatment. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:1-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 262] [Cited by in RCA: 349] [Article Influence: 31.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373-383. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:1245-1251. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Takizawa K, Oda I, Gotoda T, Yokoi C, Matsuda T, Saito Y, Saito D, Ono H. Routine coagulation of visible vessels may prevent delayed bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection--an analysis of risk factors. Endoscopy. 2008;40:179-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 235] [Cited by in RCA: 271] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Gotoda T, Yanagisawa A, Sasako M, Ono H, Nakanishi Y, Shimoda T, Kato Y. Incidence of lymph node metastasis from early gastric cancer: estimation with a large number of cases at two large centers. Gastric Cancer. 2000;3:219-225. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Hirasawa T, Gotoda T, Miyata S, Kato Y, Shimoda T, Taniguchi H, Fujisaki J, Sano T, Yamaguchi T. Incidence of lymph node metastasis and the feasibility of endoscopic resection for undifferentiated-type early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2009;12:148-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 344] [Cited by in RCA: 368] [Article Influence: 24.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sanomura Y, Oka S, Tanaka S, Numata N, Higashiyama M, Kanao H, Yoshida S, Ueno Y, Chayama K. Continued use of low-dose aspirin does not increase the risk of bleeding during or after endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2014;17:489-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cho SJ, Choi IJ, Kim CG, Lee JY, Nam BH, Kwak MH, Kim HJ, Ryu KW, Lee JH, Kim YW. Aspirin use and bleeding risk after endoscopic submucosal dissection in patients with gastric neoplasms. Endoscopy. 2012;44:114-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Matsumura T, Arai M, Maruoka D, Okimoto K, Minemura S, Ishigami H, Saito K, Nakagawa T, Katsuno T, Yokosuka O. Risk factors for early and delayed post-operative bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastric neoplasms, including patients with continued use of antithrombotic agents. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Takeuchi T, Ota K, Harada S, Edogawa S, Kojima Y, Tokioka S, Umegaki E, Higuchi K. The postoperative bleeding rate and its risk factors in patients on antithrombotic therapy who undergo gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Anderson MA, Ben-Menachem T, Gan SI, Appalaneni V, Banerjee S, Cash BD, Fisher L, Harrison ME, Fanelli RD, Fukami N. Management of antithrombotic agents for endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:1060-1070. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 378] [Cited by in RCA: 352] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Boustière C, Veitch A, Vanbiervliet G, Bulois P, Deprez P, Laquiere A, Laugier R, Lesur G, Mosler P, Nalet B. Endoscopy and antiplatelet agents. European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2011;43:445-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 28. | Yoshio T, Nishida T, Kawai N, Yuguchi K, Yamada T, Yabuta T, Komori M, Yamaguchi S, Kitamura S, Iijima H. Gastric ESD under Heparin Replacement at High-Risk Patients of Thromboembolism Is Technically Feasible but Has a High Risk of Delayed Bleeding: Osaka University ESD Study Group. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:365830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, Eikelboom J, Oldgren J, Parekh A, Pogue J, Reilly PA, Themeles E, Varrone J. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1139-1151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7917] [Cited by in RCA: 8066] [Article Influence: 504.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Hori M, Matsumoto M, Tanahashi N, Momomura S, Uchiyama S, Goto S, Izumi T, Koretsune Y, Kajikawa M, Kato M. Rivaroxaban vs. warfarin in Japanese patients with atrial fibrillation - the J-ROCKET AF study -. Circ J. 2012;76:2104-2111. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Tsuji Y, Fujishiro M, Kodashima S, Ono S, Niimi K, Mochizuki S, Asada-Hirayama I, Matsuda R, Minatsuki C, Nakayama C. Polyglycolic acid sheets and fibrin glue decrease the risk of bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastric neoplasms (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:906-912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |