Published online Nov 16, 2016. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v8.i19.701

Peer-review started: April 4, 2016

First decision: May 23, 2016

Revised: July 7, 2016

Accepted: July 20, 2016

Article in press: July 22, 2016

Published online: November 16, 2016

Processing time: 230 Days and 1.3 Hours

To investigate the effects of direct to colonoscopy pathways on information seeking behaviors and anxiety among colonoscopy-naïve patients.

Colonoscopy-naïve patients at two tertiary care hospitals completed a survey immediately prior to their scheduled outpatient procedure and before receiving sedation. Survey items included clinical pathway (direct or consult), procedure indication (cancer screening or symptom investigation), telephone and written contact from the physician endoscopist office, information sources, and pre-procedure anxiety. Participants reported pre-procedure anxiety using a 10 point scale anchored by “very relaxed” (1) and “very nervous” (10). At least three months following the procedure, patient medical records were reviewed to determine sedative dose, procedure indications and any adverse events. The primary comparison was between the direct and consult pathways. Given the very different implications, a secondary analysis considering the patient-reported indication for the procedure (symptoms or screening). Effects of pathway (direct vs consult) were compared both within and between the screening and symptom subgroups.

Of 409 patients who completed the survey, 34% followed a direct pathway. Indications for colonoscopy were similar in each group. The majority of the participants were women (58%), married (61%), and internet users (81%). The most important information source was family physicians (Direct) and specialist physicians (Consult). Use of other information sources, including the internet (20% vs 18%) and Direct family and friends (64% vs 53%), was similar in the Direct and Consult groups, respectively. Only 31% of the 81% who were internet users accessed internet health information. Most sought fundamental information such as what a colonoscopy is or why it is done. Pre-procedure anxiety did not differ between care pathways. Those undergoing colonoscopy for symptoms reported greater anxiety [mean 5.3, 95%CI: 5.0-5.7 (10 point Likert scale)] than those for screening colonoscopy (4.3, 95%CI: 3.9-4.7).

Procedure indication (cancer screening or symptom investigation) was more closely associated with information seeking behaviors and pre-procedure anxiety than care pathway.

Core tip: Direct access colonoscopy pathways are increasingly common, yet there has been relatively little scrutiny of how this practice impacts patients. This study examines the relationships among endoscopy pathway (direct vs traditional consult first), colonoscopy indication (cancer screening vs symptom investigation), information seeking behavior and pre-procedure anxiety. Patients undergoing their first colonoscopy completed questionnaires immediately prior to the procedure, before receiving sedation. The finding that direct-to-colonoscopy did not impact patient pre-procedure anxiety is reassuring. Analysis of information seeking behaviors underscores the crucial role of the family physician for referred patients who follow a direct-to-endoscopy pathway.

- Citation: Silvester JA, Kalkat H, Graff LA, Walker JR, Singh H, Duerksen DR. Information seeking and anxiety among colonoscopy-naïve adults: Direct-to-colonoscopy vs traditional consult-first pathways. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2016; 8(19): 701-708

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v8/i19/701.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v8.i19.701

As demands for prompt diagnostic and therapeutic colonoscopy have increased, direct to colonoscopy pathways have become common in many centers in North America[1]. Direct to colonoscopy, also referred to as “open access colonoscopy”, allows for provision of a colonoscopy without clinical consultation with the endoscopist prior to the day of the procedure. In an era of lengthy consultation waitlists and limited clinic resources[2], this pathway has potential to facilitate expedited clinical care for many patients. Timely access is critical because delays in diagnostic colonoscopy may result in significant delays in cancer diagnosis[3,4].

Despite being an increasingly common practice associated with appropriate utilization and diagnostic yield[5-7], there is a paucity of data regarding how direct to colonoscopy pathways affect patients. It is essential for the success of the procedure that patients receive adequate information prior to the colonoscopy, including information about bowel preparation, and risks and benefits related to the procedure[8]. Studies performed during the 1990s showed that direct to colonoscopy pathways were associated with receiving significantly less of this information prior to the procedure[9]. Since then, using the internet to access health information has become a much more common practice[10], and there are many other potential sources of information available to patients in addition to the specialist clinics. It is unknown whether the internet is commonly searched by patients prior to undergoing their first colonoscopy, what information they look for or how they use the information.

Persons undergoing an endoscopic procedure for the first time often experience heightened anxiety[11]. It is not known if patients who do not have an opportunity to address issues of concern directly during a specialist consultation experience greater anxiety or if they are more likely to seek information from other sources.

The aims of this naturalistic study were to compare information seeking behavior (including use of the internet), pre-procedure preparation and anxiety level between patients following the direct pathway and patients undergoing colonoscopy after clinical consultation with an endoscopist (consult pathway). We hypothesized that patients who follow a direct to endoscopy pathway are more likely to use the internet to obtain information regarding their procedure and may have heightened pre-procedure anxiety compared to those whose endoscopy referral pathway includes a pre-procedure consultation with the endoscopist. The implications of a colonoscopy for colon cancer screening and a colonoscopy triggered by symptoms are very different; therefore, we performed a secondary analysis considering the patient-reported indication for the procedure (symptoms or screening). An understanding of these factors will help to optimize patient preparation for their procedure and their colonoscopy experience, particularly for those following a direct to colonoscopy pathway.

From May 2011 to August 2012, consecutive adults presenting for elective outpatient colonoscopy at the two largest hospitals in Winnipeg, Canada (serving a population of 800000) were invited to complete a pre-endoscopy survey. As this was a naturalistic study, assignment of patients to direct to colonoscopy or pre-procedure consultation was not randomized. Rather, assignment followed the usual practice of the endoscopist reviewing the information provided by the referring physician to determine the appropriate care pathway. This information typically includes patient sex, date of birth and a brief description of the symptoms prompting gastrointestinal consultation. Exclusion criteria were: (1) prior endoscopy; (2) concurrent gastroscopy and colonoscopy; and (3) unable to complete the survey due to language or cognitive difficulties. The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Board at the University of Manitoba.

Sample size was estimated assuming a 2:1 allocation to the consult and direct pathways. Assuming a standard deviation of 264 in the Direct group and 128 in the Consult group are needed to detect a 1 point difference in self-reported anxiety with a type I error rate of 5% and power of 80%.

Colonoscopies were performed by a physician endoscopist (gastroenterologist or surgeon). Written information was provided to patients in advance with modest differences in content and detail between clinics. Patient information included: A description of the procedure and use of sedation; a description of the post-procedure process and follow-up; a list of potential adverse events, and instructions regarding the bowel preparation, diet, and medication use prior to the procedure.

Patients completed the survey after registering and prior to receiving sedation for their colonoscopy. The survey included items related to: (1) demographic characteristics; (2) sources of information about the colonoscopy (written information, internet, friends and family, appointment with endoscopist, telephone contact - yes/no response); (3) ranking of the three most important sources of information about the colonoscopy (10 sources listed); (4) internet use to learn about aspects of the colonoscopy (8 questions, yes/no response); (5) whether they had seen a video of a colonoscopy (yes/no response); and (6) details of type of bowel preparation used, whether they took time off work and if they completed the preparation successfully. Anxiety about the procedure was assessed with the question “how do you feel about your endoscopy today?” using a 10-item numerical rating scale, anchored by (1) very relaxed and (10) very nervous. For analysis, anxiety was characterized as “low” (a rating of 1 to 4), “moderate” (5 to 7) or “high” (8-10). Participants identified whether the colonoscopy was for cancer screening or for symptoms.

Hospital medical records of all participants were reviewed at least 3 mo after the procedure to document procedure-related processes, including indication for the colonoscopy, dose of sedative agents used, findings at colonoscopy and any adverse events.

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 15.0. Patients in the direct to colonoscopy (Direct) pathway were com–pared with patients who had received a pre-procedure consultation with the endoscopist who subsequently performed the procedure (consult pathway). Means and 95%CI or standard deviation were calculated for all variables as appropriate. The implications of a colonoscopy for colon cancer screening and a colonoscopy triggered by symptoms are very different; therefore, we performed a secondary analysis considering the patient-reported indication for the procedure (symptoms or screening). The effects of pathway (direct vs consult) were compared both within and between the screening and symptom subgroups. The 95%CIs around the estimates (mean or proportions) were used to make comparisons and the differences were considered significant if there was no overlap of 95%CIs or 95%CI around calculated differences did not cross zero.

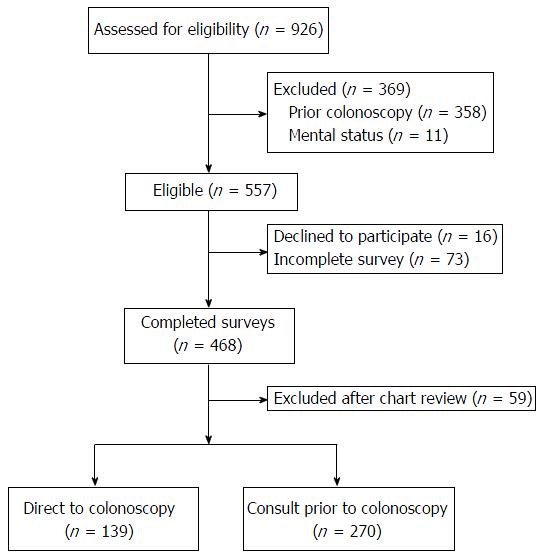

Of the 926 patients screened for study participation, 409 fulfilled study criteria and completed the pre-procedure survey (Figure 1). The most common reason for exclusion was prior endoscopy. A further 59 were excluded when chart review identified a previous endoscopy or concurrent gastroscopy. The mean age of participants was 55 years (SD 8.6). The majority of the participants were women (58%), married (61%), and internet users (81%). The demographic characteristics of those in the direct and consult groups were similar (Table 1). Virtually all patients in both groups reported receiving written information about their procedure.

| Direct (n = 139) | Consult (n = 270) | |

| % (95%CI) | % (95%CI) | |

| Highest level of education | ||

| High school or less | 35 (27-43) | 37 (31-43) |

| Trade or non-university certificate | 29 (21-37) | 35 (29-41) |

| University | 36 (28-44) | 28 (23-33) |

| Marital status - married | 60% | 62% |

| Internet user | 81% | 81% |

| Used internet to learn about colonoscopy | 29% | 32% |

| Patient indication screening | n = 76 | n = 117 |

| % of screening high risk | 60 (48-72) | 49 (40-58) |

| Patient indication symptoms | n = 63 | n = 153 |

| Bloating | 86 (77-95) | 78 (70-86) |

| Diarrhea | 78 (68-88) | 68 (60-76) |

| Abdominal cramps and/or pain | 76 (65-87) | 72 (64-80) |

| Constipation | 54 (42-66) | 61 (52-70) |

| Blood in stool | 50 (38-62) | 37 (28-46) |

| Nausea or vomiting | 35 (23-47) | 35 (26-44) |

| Weight loss | 30 (19-41) | 36 (27-45) |

| Pre-procedure information | ||

| Telephone contact | 69 (58-80) | 48 (39-57) |

| Written information | 94% | 96% |

| Age in years mean (IQR) | 56 (54-58) | 54 (53-56) |

| Sex - female | 59% | 57% |

A greater proportion of patients in the Direct group received a pre-procedure telephone call from the physician’s office with relevant pre-procedure preparation information (Direct 69% vs Consult 48%; Table 1). Receiving a pre-procedure telephone call was not associated with pre-procedure anxiety, sedation use, or information-seeking behavior (data not shown).

Ranking of the importance of information sources that were accessed to learn more about colonoscopy is described in Table 2. Both groups identified physicians as the most important source of information. Family and friends were also an important source of information for both groups, with 64% (56%-72%) in the direct group and 53% (47%-59%) in the Consult group rating them among the three most important sources of information. As expected, those following the direct pathway obtained information from a specialist physician less often, and were more likely to rate information from a family physician among the top three most important information sources [59% (51%-67%) vs 39% (33%-45%)]. The use and importance of other information sources, including the internet, did not differ between the two groups.

| Most important | Among top three most important | |||

| Direct | Consult | Direct | Consult | |

| % (95%CI) | % (95%CI) | % (95%CI) | % (95%CI) | |

| Any physician | 51 (43-59) | 69 (63-75) | 81 (75-88) | 89 (85-93) |

| Family physician | 37 (29-45) | 26 (21-31) | 59 (51-67) | 39 (33-45) |

| Specialist physician | 14 (8-20) | 43 (37-49) | 22 (15-29) | 50 (44-56) |

| Family and friends | 13 (7-19) | 10 (6-14) | 64 (56-72) | 53 (47-59) |

| Internet | 7 (3-11) | 4 (2-6) | 20 (13-27) | 18 (13-23) |

| Other | 3 (0-6) | 3 (1-5) | 20 (13-27) | 13 (9-17) |

The rate of general internet use was 81% in both groups (n = 301), with about 30% reporting they used the internet to learn more about colonoscopy. The pattern of responses shown in Table 3 suggests that among the respondents who used the internet to obtain information about colonoscopy (n = 301), there was interest in a wide range of questions which did not differ between care pathways. Considering the indication for colonoscopy, those referred for symptoms accessed internet health information more often than those in the screening group [48% (40%-56%) vs 28% (20%-36%)]. Despite the wealth of information available on the internet, including well-produced videos, only 1 in 6 patients had seen a video of a colonoscopy prior to the procedure.

| Care pathway | Indication | |||

| Direct (n = 104) | Consult (n = 197) | Screening (n = 166) | Symptoms (n = 135) | |

| % (95%CI) | % (95%CI) | % (95%CI) | % (95%CI) | |

| What is a colonoscopy | 29 (20-38) | 32 (26-39) | 23 (16-31) | 38 (31-46) |

| How to prepare for colonoscopy | 16 (8-23) | 24 (17-30) | 15 (9-22) | 26 (19-33) |

| What happens during colonoscopy | 20 (12-28) | 26 (19-32) | 17 (10-24) | 30 (22-37) |

| How much time does a colonoscopy take | 13 (6-19) | 20 (14-26) | 14 (8-20) | 21 (15-28) |

| What to expect after colonoscopy | 11 (5-18) | 18 (12-24) | 12 (6-18) | 19 (13-26) |

| Why colonoscopy is done | 30 (21-40) | 28 (22-35) | 19 (12-26) | 37 (29-45) |

| Risks of colonoscopy | 19 (11-27) | 22 (16-28) | 16 (10-23) | 25 (18-32) |

| What is a biopsy | 11 (5-18) | 14 (9-19) | 9 (4-14) | 17 (11-23) |

| Saw video of colonoscopy | 24 (15-33) | 17 (11-22) | 19 (12-25) | 20 (13-26) |

There was no difference in the type of bowel preparation used or the self-reported completion of bowel preparation between the two groups (Table 4). Most respondents took time off work to complete bowel preparation, but there was no difference between the Direct and Consult care pathways.

| Direct (n = 139) | Consult (n = 270) | |

| % (95%CI) | % (95%CI) | |

| Bowel prep | ||

| Picosulfate and magnesium oxide | 69 (60-76) | 71(65-77) |

| Polyethylene glycol | 17 (11-24) | 14 (10-18) |

| Other | 14 (8-20) | 15 (11-19) |

| Completion of bowel prep | 98% | 98% |

| Time off work for bowel prep | ||

| Full-time workers (n = 188) | 56 (43-69) | 64 (56-72) |

| Part-time workers (n = 52) | 42 (20-64) | 50 (29-71) |

| Sedation | ||

| Midazolam (mg) | 5.6 (5.2-5.9) | 4.7 (4.5-4.9) |

| Fentanyl (μg) | 106 (100-111) | 93 (89-97) |

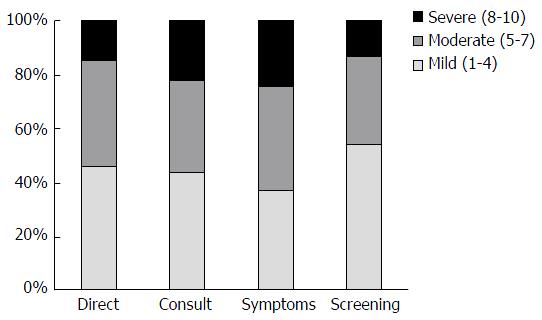

Overall, 20% of participants reported high pre-procedure anxiety. In both care pathways, females reported significantly higher pre-procedure anxiety than males [overall females 5.3 (5.0-5.7), males 4.3 (3.9-4.7); 95%CI for difference 0.76-1.9]. There were no differences in the pre-procedure anxiety levels among individuals in the Direct group compared with the Consult group [mean 4.7 (95%CI: 4.3-5.2) vs 5.0 (95%CI: 4.6-5.3)]. Similarly, there was no stastical differences in proportions reporting low, moderate or high pre-procedure anxiety, comparing the Direct and Consult groups (Figure 2). Mean pre-procedure anxiety was lower among those undergoing screening colonoscopy, but the difference was significant only within the Consult group (males 4.2 vs females 5.4; 95%CI for difference 0.5-2.0). There were 311 participants for whom the self-reported indication matched the indication documented in the medical record. In sensitivity analysis, the relationship between procedure indication and pre-procedure anxiety was observed among this group for both care pathways (Direct 4.4 vs 5.4; Consult 4.1 vs 5.5). Mean anxiety levels among those for whom the patient-reported and documented indication were discordant were similar to the population mean. In the Direct group, the relationship between pre-procedure anxiety and indication was attenuated (screening 4.2, non-screening 4.6). Among the Consult group, the relationship was reversed, with higher anxiety levels reported by those undergoing screening colonoscopy (5.1 vs 4.8). This difference persisted even when those identified as high-risk were excluded from the analysis (data not shown).

Patients in the Direct group received more midazolam (5.4 mg vs 4.6 mg, 95%CI: 0.41-1.2 mg) and fentanyl (105 μg vs 93 μg; 95%CI: 5-20 μg). This association between direct pathway and midazolam use was also observed within the screening and symptom sub-groups (data not shown). Midazolam and fentanyl doses were unrelated to self-rated pre-procedure anxiety, indication for the procedure or duration of the procedure (data not shown). There were no sedation or procedure related adverse events reported, based on the chart review.

This observational study clarifies the real-world effects of referral pathway upon the behaviors and experiences of colonoscopy-naïve patients. We hypothesized that those in the direct (open access) pathway would display more information seeking behaviors and may experience more anxiety related to the procedure given that they did not have the benefit of a consultation with the physician endoscopist prior to the day of their procedure. We found that information seeking behaviors and anxiety were more closely associated with the indication for the procedure (colon cancer screening vs for diagnosis of symptoms) than by the referral pathway. This illustrates the intricacy of designing referral pathways to optimize the utilization of scarce clinical and endoscopy resources while providing care which meets the needs of the patient. It also underscores the importance of primary care physicians in the continuum of care.

The pattern of information seeking behavior did not differ between the two care pathways. Even with the plethora of electronic and other resources available, the patient-physician relationship was paramount for obtaining information regarding colonoscopy. Patients following a direct pathway received this information from a primary care physician, while patients in the Consult group received this information from an endoscopist.

This study was conducted in Canada where there is one of the highest rates of internet penetration[12] and the majority of the population has used the internet to access health information[10]. Over 80% of patients in our study were internet users; however, only 30% of them used the internet to learn more about colonoscopy. Patients who accessed internet health information sought to answer fundamental questions related to what a colonoscopy is and why is it done, with fewer reporting having delved more deeply into details such as biopsy or the risks of colonoscopy. This observation is concerning given a narrative review of the relationships between lower endoscopy and clinical outcomes which concluded that providing written information and reminders improve adherence to procedures, but that a large proportion of patients have poor comprehension of the risks, benefits and alternatives to colonoscopy[13]. The general nature of information sought by participants in our study indicates a need for additional educational initiatives to increase patient knowledge about the procedure which encompasses more than instruction for achieving a quality bowel preparation.

The role of the internet in educating patients about colonoscopy prior to their procedure has not been studied. Given that over 80% of patients in this study were internet users, there is opportunity to develop internet resources or more proactively use appropriate existing resources to support physicians in preparing patients for endoscopic procedures. Advantages of the internet are that it is accessible for most people, can present video materials easily, and allows the user to choose how much material to review, depending on information preferences and previous knowledge. Video materials have the advantage that they can present information vividly and may impart information about the procedure more easily than text-based information. There are currently resources on the internet that provide realistic and positive depictions of the patient experience before and during a colonoscopy[14,15], but they do not appear to be widely used by patients preparing for their first colonoscopy.

We hypothesized that increased pre-procedure anxiety might be an unintended and unrecognized consequence of direct to colonoscopy pathways. However, in our study of colonoscopy-naïve individuals, pre-procedure anxiety was similar regardless of referral pathway. There were a significant minority (20%) who reported high pre-procedure anxiety, with higher anxiety levels reported by women than by men. There is one other report of the relationship between direct to colonoscopy pathway and pre-procedure anxiety[11]. That study was also an observational study, but included patients who had previously undergone an endoscopic procedure as well as patients undergoing gastroscopy. Nevertheless, similar to our study, the direct to colonoscopy pathway was not associated with increased pre-procedure anxiety[11]. We found, understandably, that participants undergoing colonoscopy for symptom investigation reported greater pre-procedure anxiety than participants whose endoscopy was for colorectal cancer screening. Among the entire group, the majority of participants reported moderate or high anxiety related to their procedure, irrespective of the pathway or indication.

Clearly, allaying pre-procedure anxiety may be helpful in optimizing the experience of patients undergoing a colonoscopy, yet there have been few studies which have evaluated interventions to decrease pre-procedure anxiety[16-18]. For colonoscopy-naïve patients, education has been found to effectively decrease anxiety when delivered either as a ten minutes video at the pre-procedure visit[17] or as a detailed information pamphlet about colonoscopy[19] in addition to standard written information. Provision of written instruction and information was associated with decreased pre-procedure anxiety in a cohort of patients who had undergone a previous endoscopic procedure[18].

The content of the information provided is also relevant to pre-procedure anxiety. Provision of a colonoscopy pamphlet developed by the American Gastroenterology Association which explained all aspects of colonoscopy and why it is done in addition to “standard colonoscopy preparation instructions” (which focused primarily on the details of the bowel prep) may decrease pre-procedure anxiety[19]. Interestingly, in a randomized study in which participants were invited to watch an informational video in addition to receiving standard information, offering the choice did not result in a reduction in pre-procedure anxiety, yet all patients who viewed the video experienced less pre-procedure anxiety[17].

An unexpected finding of our study was that patients following the direct pathway received higher doses of sedative medications than patients who had a pre-procedure consult. This was not significantly associated with self-reported pre-procedure anxiety, indication for the procedure, or duration of the procedure. While the lack of association between pre-procedure anxiety and sedation requirements during colonoscopy has been reported[20], referral pathway has not previously been identified as a risk factor for increased sedation requirement. The relationship between referral pathway and sedation use during colonoscopy merits further study, not only to improve our limited understanding of the complex factors contributing to sedation requirements[21-23], but also to determine whether inclusion of this variable would enhance clinical scoring systems to prospectively identify patients with high sedation requirements[23].

A potential consequence of direct to colonoscopy is inadequate instruction regarding the bowel preparation required for the procedure. Adequacy of bowel preparation is considered a quality indicator in colonoscopy[24] and is particularly relevant for screening for colorectal cancer, the most common indication for colonoscopy in our patient sample, and in most endoscopy units. Self-reported successful completion of bowel preparation was similar in both care pathways. The quality of bowel preparation was not evaluated because this was not systematically recorded by the endoscopists. The work of other investigators suggests that open access does not compromise the bowel preparation with up to 96% of patients achieving adequate bowel preparation using a split-dose regimem[25].

The primary strength of this study is the use of a naturalistic design to explore a topic about which relatively little is known. This provides insight into patient experiences and behaviors in a real-world scenario reflective of clinical practice.

The use of an observational design is also a limitation. There were multiple endoscopists involved who used several similar, non-identical, pre-procedure information pamphlets. Assignment to the direct to endoscopy pathway was a decision made by the endoscopist without reference to pre-determined standardized criteria or as part of a randomized study design. This may have introduced bias into the study; however, it reflects clinical practice and the distribution of patients between the two pathways was similar at the two study sites. Although the difference was relatively small (11%), there were more patients undergoing screening in the Direct to colonoscopy group compared to the Consult group. This is not unexpected given that age is indicated on the referral and is an indication for screening colonoscopy. Nevertheless, there were no major differences in the demographic characteristics of the two patient groups and the relative differences in pre-procedure anxiety and information seeking behaviors between those who were undergoing colonoscopy for unexplained symptoms and those who were undergoing screening colonoscopy were similar in both care pathways.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that the ramifications of open access colonoscopy encompass far more than improved efficiency and cost savings. Patients in the direct pathway relied upon their family doctor to obtain information about their procedure. In an era of open access colonoscopy, it may be especially important that primary care physicians can provide accurate and relevant information regarding colonoscopy to their patients. This includes specifics about the procedure, the preparation, the risks and the rationale for its use, which is the information that patients were most likely to seek using the internet. Preparation for endoscopy is a complex and multifactorial process which involves more than ensuring an adequate bowel preparation. The value of primary care counseling is underscored by a study in which those who received primary care counseling had greater participation in a colon cancer screening program and required less sedation during their procedure[26].

Colonoscopy-naïve patients who were assigned to a direct to colonoscopy pathway demonstrated similar information seeking behavior, use of the internet as an information source, completion of the bowel prep and levels of pre-procedure anxiety as those who had a pre-procedure outpatient consultation. However, there was a relevant minority of patients with high pre-procedure anxiety which was higher in women and in individuals undergoing a colonoscopy for symptom investigation. Future studies should address ways of optimizing preparation of patients for the colonoscopy and reducing pre-procedure anxiety.

We thank all the patients who participated in this study and the endoscopy unit staff who assisted with recruiting them. As well, we thank the Health Sciences Center Medical Staff Council who provided funding for this study.

Direct access colonoscopy pathways are increasingly common as health care systems strive to expedite care and control costs. This is associated with appropriate use and diagnostic yield, but other impacts have not been well-described.

This study of colonoscopy-naïve patients investigates information use and anxiety in patients undergoing direct access colonoscopy and compares this with patients who have an initial consult prior to their colonoscopy procedure.

Open access colonoscopy has ramifications beyond efficiency gains and cost savings. Physicians play a key role in informing patients about colonoscopy and primary care physicians play an especially important role in an open access pathway. Pre-procedure anxiety is more closely associated with patient reported indication for the procedure than with referral pathway.

This study supports the practice of direct access colonoscopy. Patients undergoing direct access colonoscopy do not have increased anxiety and access information about their procedure similar to patients having a specialist consult prior to the procedure. Referral pathways must be responsive to the needs of patients and attentive to the role of referring clinicians to ensure adequately informed and prepared patients.

This is an interesting study looking at difference in anxiety between open access and consult first pathways to colonoscopy. The research is well-designed and the overall structure of the manuscript is complete.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Canada

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Chaptini L, Saligram S, Zhang QS S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Pike IM. Open-access endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2006;16:709-717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Leddin D, Bridges RJ, Morgan DG, Fallone C, Render C, Plourde V, Gray J, Switzer C, McHattie J, Singh H. Survey of access to gastroenterology in Canada: the SAGE wait times program. Can J Gastroenterol. 2010;24:20-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Singh H, Khan R, Giardina TD, Paul LW, Daci K, Gould M, El-Serag H. Postreferral colonoscopy delays in diagnosis of colorectal cancer: a mixed-methods analysis. Qual Manag Health Care. 2013;21:252-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sey MS, Gregor J, Adams P, Khanna N, Vinden C, Driman D, Chande N. Wait times for diagnostic colonoscopy among outpatients with colorectal cancer: a comparison with Canadian Association of Gastroenterology targets. Can J Gastroenterol. 2012;26:894-896. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Gimeno García AZ, González Y, Quintero E, Nicolás-Pérez D, Adrián Z, Romero R, Alarcón Fernández O, Hernández M, Carrillo M, Felipe V. Clinical validation of the European Panel on the Appropriateness of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (EPAGE) II criteria in an open-access unit: a prospective study. Endoscopy. 2012;44:32-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Morini S, Hassan C, Meucci G, Toldi A, Zullo A, Minoli G. Diagnostic yield of open access colonoscopy according to appropriateness. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:175-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Charles RJ, Cooper GS, Wong RC, Sivak MV, Chak A. Effectiveness of open-access endoscopy in routine primary-care practice. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:183-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kazarian ES, Carreira FS, Toribara NW, Denberg TD. Colonoscopy completion in a large safety net health care system. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:438-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Staff DM, Saeian K, Rochling F, Narayanan S, Kern M, Shaker R, Hogan WJ. Does open access endoscopy close the door to an adequately informed patient? Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:212-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Underhill C, Mckeown L. Getting a second opinion: health information and the Internet. Health Rep. 2008;19:65-69. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Mahajan RJ, Agrawal S, Barthel JS, Marshall JB. Are patients who undergo open-access endoscopy more anxious about their procedures than patients referred from the GI clinic? Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:2505-2508. [PubMed] |

| 12. | de Argaez E. Top 50 countries with highest internet penetration rates. Internet World Stats: usage and population statistics 2014; Available from: http://www.internetworldstats.com/top25.htm. |

| 13. | Coombes JM, Steiner JF, Bekelman DB, Prochazka AV, Denberg TD. Clinical outcomes associated with attempts to educate patients about lower endoscopy: a narrative review. J Community Health. 2008;33:149-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Colonoscopy: What Patients Can Expect. 2009. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eA1PIMa1ULg. |

| 15. | Stand up to Cancer. Katie Couric’s Colonoscopy for SU2C, 2000. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=15JsYSZIT-Q. |

| 16. | Pearson S, Maddern GJ, Hewett P. Interacting effects of preoperative information and patient choice in adaptation to colonoscopy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:2047-2054. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Luck A, Pearson S, Maddern G, Hewett P. Effects of video information on precolonoscopy anxiety and knowledge: a randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;354:2032-2035. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Kutlutürkan S, Görgülü U, Fesci H, Karavelioglu A. The effects of providing pre-gastrointestinal endoscopy written educational material on patients' anxiety: a randomised controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47:1066-1073. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Shaikh AA, Hussain SM, Rahn S, Desilets DJ. Effect of an educational pamphlet on colon cancer screening: a randomized, prospective trial. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:444-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chung KC, Juang SE, Lee KC, Hu WH, Lu CC, Lu HF, Hung KC. The effect of pre-procedure anxiety on sedative requirements for sedation during colonoscopy. Anaesthesia. 2013;68:253-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hazeldine S, Fritschi L, Forbes G. Predicting patient tolerance of endoscopy with conscious sedation. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1248-1254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bal BS, Crowell MD, Kohli DR, Menendez J, Rashti F, Kumar AS, Olden KW. What factors are associated with the difficult-to-sedate endoscopy patient? Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:2527-2534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Braunstein ED, Rosenberg R, Gress F, Green PH, Lebwohl B. Development and validation of a clinical prediction score (the SCOPE score) to predict sedation outcomes in patients undergoing endoscopic procedures. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:72-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rex DK, Schoenfeld PS, Cohen J, Pike IM, Adler DG, Fennerty MB, Lieb JG, Park WG, Rizk MK, Sawhney MS. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:31-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 649] [Cited by in RCA: 834] [Article Influence: 83.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | MacPhail ME, Hardacker KA, Tiwari A, Vemulapalli KC, Rex DK. Intraprocedural cleansing work during colonoscopy and achievable rates of adequate preparation in an open-access endoscopy unit. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:525-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Boguradzka A, Wiszniewski M, Kaminski MF, Kraszewska E, Mazurczak-Pluta T, Rzewuska D, Ptasinski A, Regula J. The effect of primary care physician counseling on participation rate and use of sedation in colonoscopy-based colorectal cancer screening program--a randomized controlled study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:878-884. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |