Published online Oct 16, 2016. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v8.i18.663

Peer-review started: February 9, 2016

First decision: March 23, 2016

Revised: July 18, 2016

Accepted: August 6, 2016

Article in press: August 8, 2016

Published online: October 16, 2016

Processing time: 254 Days and 2.7 Hours

To investigate the efficacy of prior minimal endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) to prevent pancreatitis related to endoscopic balloon sphincteroplasty (EBS).

After bile duct access was gained and cholangiogram confirmed the presence of stones < 8 mm in the common bile duct at endoscopic retrograde cholangiography, patients were subjected to minimal EST (up to one-third of the size the papilla) plus 8 mm EBS (EST-EBS group). The incidence of pancreatitis and the difference in serum amylase level after the procedure were examined and compared with those associated with 8-mm EBS alone in 32 patients of historical control (control group).

One hundred and five patients were included in the EST-EBS group, and complete stone removal was accomplished in all of them. The difference in serum amylase level after the procedure was - 25.0 (217.9) IU/L in the EST-EBS group and this value was significantly lower than the 365.5 (576.3) IU/L observed in the control group (P < 0.001). The incidence of post-procedure pancreatitis was 0% (0/105) in the EST-EBS group and 15.6% (5/32) in the control group (P < 0.001).

Prior minimal EST might be useful to prevent the elevation of serum amylase level and the occurrence of pancreatitis related to EBS.

Core tip: We evaluated the efficacy of prior minimal endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) to prevent pancreatitis related to endoscopic balloon sphincteroplasty (EBS). One hundred and five patients with bile duct stones < 8 mm were subjected to minimal EST (up to one-third of the size the papilla) plus 8 mm EBS (EST-EBS group). The incidence of pancreatitis and the difference in serum amylase level after the procedure were examined and compared with those associated with 8-mm EBS alone in 32 patients of historical control (control group). The difference in serum amylase level after the procedure in the EST-EBS group was significantly lower than that observed in the control group (P < 0.001). The incidence of post-procedure pancreatitis was 0% (0/105) in the EST-EBS group and 15.6% (5/32) in the control group (P < 0.001).

- Citation: Kanazawa R, Sai JK, Ito T, Miura H, Ishii S, Saito H, Tomishima K, Shimizu R, Sato K, Hayashi M, Watanabe S, Shiina S. Prior minimal endoscopic sphincterotomy to prevent pancreatitis related to endoscopic balloon sphincteroplasty. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2016; 8(18): 663-668

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v8/i18/663.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v8.i18.663

Preventing major adverse events related to endoscopic interventions to remove bile duct stones is a matter of great concern to endoscopists and patients. Endoscopic balloon sphincteroplasty (EBS) using a 6-8 mm balloon is associated with a lower frequency of hemorrhage and perforation compared with endoscopic sphincterectomy (EST)[1-4]. However, EBS alone is rarely performed these days because of the high risk of acute pancreatitis and concern for fatal pancreatitis[2,5,6]. Several studies have recently shown that EST plus large balloon sphincteroplasty (LBS) carries a low risk of post-procedure pancreatitis (0%-3%)[7,8], although there have been no comparative studies between LBS alone and EST followed by LBS.

In the present study, we investigated the efficacy of prior minimal EST (up to one third of the papilla) to prevent pancreatitis related to EBS by comparing a group subjected to EBS alone with another subjected to minimal EST followed by EBS.

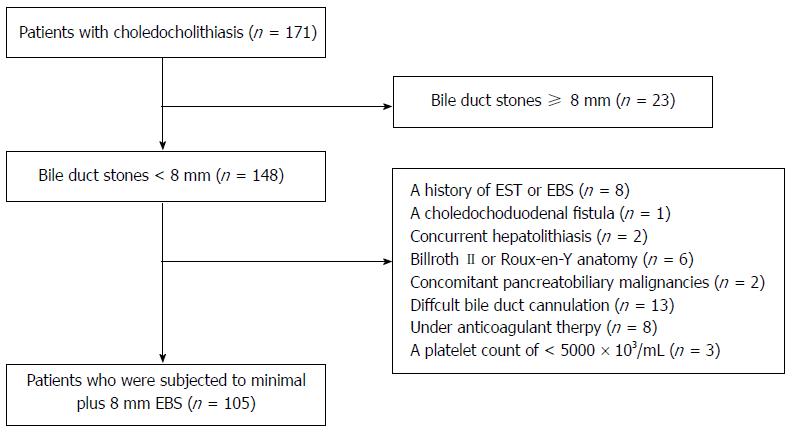

Between October 2010 and March 2014, patients aged 18 years or older were prospectively included in the current study after bile duct access was gained and cholangiogram confirmed the presence of bile duct stones (EST-EBS group). Patients were excluded if they had a history of EST or EBS, a choledochoduodenal fistula, concurrent hepatolithiasis, Billroth II or Roux-en-Y anatomy, or a concomitant pancreatobiliary malignancy. Patients with conditions suggesting difficult bile duct cannulation, such as requirement of pancreatic guide-wire, pancreatic stent, precut sphincterotomy, pancreatic sphincterectomy or the Rendezvous technique for difficult bile duct access, were also excluded. Patients under anticoagulant therapy or with a coagulopathy (international normalized ratio > 1.3, partial thromboplastin time greater than twice that of control) and a platelet count of < 50000 × 103/μL were excluded and subjected to EBS only. Patients with stones ≥ 8 mm were subjected to limited EST (up to half of the papilla) plus LBS and excluded from the current study. The size of bile duct stones was measured on endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) images corrected for magnification using the diameter of the endoscope as a reference.

As the historical control, 32 consecutive patients, who fulfilled the same inclusion criteria as the EST-EBS group and had undergone 8 mm EBS alone between November 2009 and December 2011, served as the control group.

Informed consent was obtained from all patients. The study was approved by the ethics committee of our institution.

ERCP was performed using a side-viewing duodenoscope (JF-240, JF-260V, TJF-260; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Electrocautery was carried out using a 120-watt endocut current (ERBE International, Erlangen, Germany)[9,10]. One of four trainees (> 100 ERCPs) accompanied by one specialist (> 10000 ERCPs) performed the procedures. Following preparation with pharyngeal anesthesia and intravenous injection of midazolam (0.06 mg/kg), ERCP was performed. After bile duct access was gained and cholangiogram confirmed the presence of bile duct stones ≤ 8 mm, minimal EST followed by 8-mm EBS was performed. Minimal EST up to one third of the papilla was performed with a 30-mm-pull-type sphincterotome (Clever Cut 3; KD-V41M, Olympus) under the guidewire. EBS was performed with wire-guided hydrostatic balloon catheters (Eliminator, ConMed, NY; balloon length 3 cm, maximum inflated outer diameter 8 mm) placed across the papilla. The balloon was centered at the sphincter, and was dilated to the size of the lower bile duct or 8 mm, whichever was smaller. Inflation time was 30 s.

After the procedure, the stones were retrieved with an extraction balloon under the guidewire. When necessary, a mechanical lithotripter (Lithocrush, Olympus) was used to crush stones. An occlusion cholangiogram was obtained at the end of the procedure. Biliary stents or nasobiliary drains were placed when the stones were not completely removed. None of the patients had prophylactic pancreatic stents placed before or after the procedure.

Each patient was kept under fasting conditions after the procedure and was carefully monitored for the development of any adverse events. Physical examination and laboratory tests were performed daily after the procedure. Serum amylase was checked in all patients before and 24 h after the procedure. If the acute condition had settled and the serum concentration of amylase was below 375 IU/L (normal range: < 125 IU/L), the patient was allowed to take a meal.

Definitions of individual adverse events were similar to those given by Cotton et al[11]. The severity of adverse events was graded according to the length of hospitalization. Mild adverse events required 2 to 3 d of hospitalization; moderate adverse events required 4 to 10 d; and severe adverse events requiring more than 10 d of hospitalization[11,12]. Procedure-induced pancreatitis was defined as new or worsened abdominal pain associated with a serum concentration of amylase three or more times the upper limit of normal at 24 h after the procedure, requiring hospitalization or prolongation of planned admission[11,12]. Hemorrhage was considered clinically significant only if there was clinical evidence of bleeding, such as melena or hematemesis, with an associated decrease of at least 2 g per deciliter in hemoglobin concentration, or the need for a blood transfusion[11,12]. Cholangitis was diagnosed when there was right upper quadrant abdominal tenderness, body temperature of > 38 °C, and elevated serum concentrations of liver enzymes. Acute cholecystitis was diagnosed based on suggestive clinical and radiographic signs. Perforation referred to retroperitoneal or bowel-wall perforation documented by any radiographic technique[11,12].

The incidences of procedure related pancreatitis and the differences in serum amylase levels from baseline at 24 h after the procedure were examined in both groups of patients. Secondary outcome measures included the stone clearance rate, and the number of ERCPs required for complete stone clearance. Complete stone clearance was defined as the absence of filling defects on the occlusion cholangiogram as noted by the endoscopists.

Statistical analyses were performed using statistical software (SPSS version 17.0 for Windows). Data were presented as the mean ± SD and were compared using paired t test. Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparing continuous data with skewed distribution in the two groups. A χ2 test with Yate’s correction was used to analyze gender. The difference in serum amylase level after the procedure and the incidence of post-procedure pancreatitis were compared using Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Statistical significance was defined as a P value < 0.05 (two tailed).

Among the 171 consecutive patients with choledocholithiasis who were enrolled in the current study, 8 patients were excluded for a history of EST and/or EBS, 1 was excluded for a choledochoduodenal fistula, 2 for concurrent hepatolithiasis, 6 for Billroth II or Roux-en-Y anatomy, 2 for concomitant biliary malignancies, 13 were excluded for difficult bile duct canulation; besides, 8 patients who were under anticoagulant therapy or had a coagulopathy and 3 with a platelet count of < 50000 × 103/μL were also excluded. Twenty-three patients with stones larger than 8 mm were subjected to limited EST plus LBS (Figure 1).

Consequently, there were 105 patients in the EST-EBS group. The clinical characteristics of the patients in each group are shown in Table 1. The two groups were similar with respect to demographic features. Minimal EST plus 8 mm EBS was successfully performed in all patients. The waist of the balloon at the papilla was observed under fluoroscopic examination in both groups of patients during inflation of the balloon, and, after inflation, the waist remained in 9 (8.6%) patients of the EST-EBS group and 3 (8.7%) of the control group because of the stenosis or small diameter of the distal bile duct.

| EST-EBS(n = 105) | EBS alone(n = 32) | P value | |

| Sex (female/male) | 61/44 | 17/15 | NS |

| Age (yr) | 70.2 (29-83) | 71.4 (28-88) | NS |

| Maximum CBD diameter (mm) | 8.1 ± 4.5 | 7.7 ± 3.9 | NS |

| Maximum stone diameter (mm) | 6.6 ± 1.9 | 4.9 ± 1.8 | NS |

| Stone number | 2.1 ± 1.4 | 2.3 ± 1.7 | NS |

| Serum amylase (IU/L) | 148.2 ± 301.6 | 164.5 ± 136.3 | NS |

| Periampullary diverticulum, n (%) | 41 (32.5) | 10 (31.7) | NS |

| Acute cholangitis before ERCP, n (%) | 44 (16.6) | 6 (21.8) | NS |

| Acute cholecystitis before ERCP, n (%) | 3 (2.8) | 1 (3.1) | NS |

Complete duct clearance was accomplished in both groups of patients. The stones were completely removed in the first session in all patients of the EST-EBS group and in 27 (84.3%) of the control group (P < 0.001). The other 5 (15.7%) patients of the control group required 2 sessions. Mechanical lithotripsy was required in 2 (1.9%) patients of the EST-EBS group, and in one (4.3%) of the control group due to stenosis or small diameter of the distal bile duct (Table 2).

| EST-EBS(n = 105) | EBS alone(n = 32) | P value | |

| n (%) sessions required | |||

| 1 | 105 (100) | 27 (84.3) | < 0.001 |

| 2 | 5 (15.7) | ||

| Complete removal, n (%) | 105 (100) | 32 (100) | NS |

| Mechanical lithotripsy, n (%) | 2 (1.9) | 1 (4.3) | NS |

| Pancreatogram, n (%) | 34 (32.7) | 10 (31.2) | NS |

| Serum amylase (IU/L) | -25.0 ± 217.9 | 365.5 ± 576.3 | < 0.001 |

| Post procedure pancreatitis | 0 (0) | 5 (15.6) | < 0.001 |

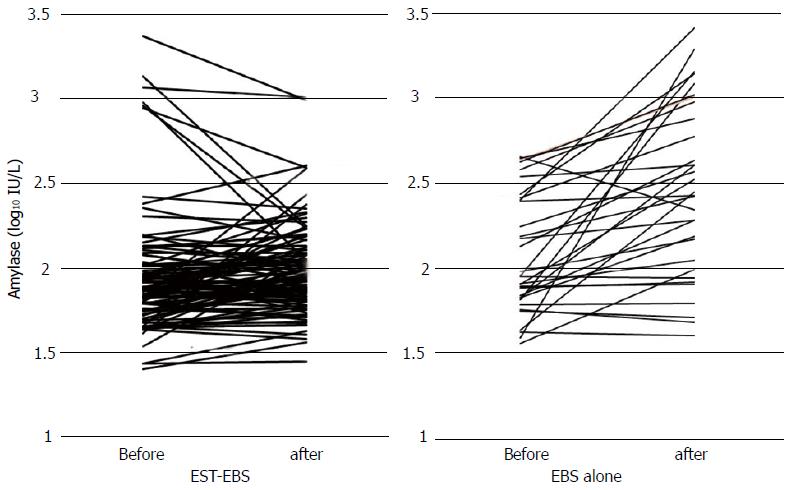

The mean (SD) serum amylase levels before and after the procedure were 148.2 (301.6) IU/L and 123.3 (138.7) IU/L in the EST-EBS group, and 164.5 (136.3) IU/L and 530.4 (604.4) IU/L in the control group. The difference in serum amylase level after the procedure was - 25.0 (217.9) IU/L in the EST-EBS group and 365.5 (576.3) IU/L in the control group (P < 0.001) (Figure 2). The incidence of post-procedure pancreatitis was 0% (0/105) in the EST-EBS group and 15.6% (5/32) in the control group (P < 0.001). Cholangitis occurred in 3.1% (1/32) of the patients in the control group. None of the other patients in either group experienced any adverse event such as hemorrhage, perforation or cholecystitis within 7 d after the procedure.

EBS using a 6- to 8-mm balloon is associated with a lower frequency of hemorrhage and perforation compared with EST[1,2], and allows preservation of sphincter of Oddi function[3,4]. However, EBS alone has been associated with a high risk of acute pancreatitis[2,5,6]. In the study by Disario et al[6], pancreatitis occurred in 17.9% of patients subjected to EBS and in 3.3% of those subjected to EST; besides, 2 (1.7%) patients in the EBS group died because of severe pancreatitis. In addition, in five prospective randomized controlled trials of EBS vs EST[5,6,13-15], the incidence of pancreatitis after EBS varied between 4.9% and 20%. Furthermore, EBS was identified as an independent risk factor of post-ERCP pancreatitis in a large prospective multicenter study, including one death related to pancreatitis after EBS[16]. Therefore, it is necessary to modify the EBS technique to reduce the risk of pancreatitis.

EST plus LBS for the extraction of large bile duct stones has shown a low incidence of pancreatitis (0%-4.0%) in large-scale studies[8,9,17], although pancreatitis was thought to be closely related to balloon sphincteroplasty. Attasaranya et al[8]. suggested that EST performed before LBS may result in a separation between the pancreatic and biliary orifices, and balloon dilation forces that are exerted away from the pancreatic duct might lead to a lower risk of postprocedure pancreatitis compared with EBS alone.

In the current study, we performed minimal EST before 8-mm EBS in 105 patients with bile duct stones ≤ 8 mm in diameter. We successfully extracted the stones in all the patients with none of them experiencing post-procedure pancreatitis. Furthermore, in this group the difference in serum amylase level between the baseline value and that after the procedure was significantly lower and the incidence of post-procedure pancreatitis was significantly lower compared with the control group subjected to EBS alone. The objective of minimal EST was to separate the pancreatic orifice from the biliary orifice to prevent pancreatitis related to EBS, and to avoid bleeding and perforation related to standard EST. The objective of EBS after EST was to maximize the biliary sphincterotomy orifice and thereby enable free access of a retrieval balloon catheter or basket to the common channel. Actually, all patients in the current study showed a waist at the papilla during balloon dilation after minimal EST, and if the sphincter is not dilated by a balloon, resistance may occur at the biliary outlet during retrieval of the stone using a basket or retrieval balloon catheter; besides papillary edema or spasm may obstruct the flow of pancreatic juice and the pancreas would be injured as a result of these manipulations[18].

There are some limitations in comparing the current data with previous data from the viewpoint of efficacy and safety. First, the procedure for endotherapy of bile duct stones may depend on the endoscopist, although a trainee attempted the procedure and was supported by an expert on each occasion in our study. Second, our series included patients with a mean age of 70 years, whereas the median age was 49 years in the prospective multicenter trial done in the United States that showed a higher rate of pancreatitis after EBS[6]. Therefore the risk associated with minimal EST plus EBS in younger patients was not fully estimated in the current study. Third, the true advantage of one technique over the other can only be assessed in a randomized controlled trial, while the current study was conducted prospectively and the results were compared with a historical control. Fourth, although minimal EST plus 8-mm EBS resulted in a high cost due to the use of a balloon catheter and a sphincterotomy knife, preventing post-procedure pancreatitis was undoubtedly worth the higher cost. Fifth, long-term adverse events including cholangitis, recurrence of bile duct stones, and cholecystitis are an important problem and should be assessed in future studies.

In conclusion, prior minimal EST is expected to significantly reduce the risk of pancreatitis related to EBS for the treatment of patients with bile duct stones. Further studies involving a larger series of patients are required to confirm the reliability of the present results.

Endoscopic balloon sphincteroplasty (EBS) is associated with lower frequency of bleeding and perforation compared with endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST), as well as preservation of sphincter of Oddi function. But, EBS has a higher risk of acute pancreatitis and concern for fatal pancreatitis. It is necessary to modify the EBS technique to reduce the risk of pancreatitis.

Prior minimal EST is expected to significantly reduce the risk of pancreatitis related to EBS for the treatment of patients with bile duct stones.

The paper may interest readers because prior minimal EST might be useful to prevent the elevation of serum amylase level and the occurrence of pancreatitis related to EBS.

The objective of minimal EST was to separate the pancreatic orifice from the biliary orifice to prevent pancreatitis related to EBS, and to avoid bleeding and perforation related to standard EST. The objective of EBS after EST was to maximize the biliary sphincterotomy orifice and thereby enable free access of a retrieval balloon catheter or basket to the common channel.

In this article, the authors found that the prior minimal EST might be useful to prevent the elevation of serum amylase level and the occurrence of pancreatitis. This new method would maybe reduce the risk of post ERCP pancreatitis. This is a well-written paper containing interesting results which merit publication.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty Type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of Origin: Japan

Peer-Review Report Classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P- Reviewer: Chow WK, Cuadrado-Garcia A, Giannopoulos GA, Luo HS S- Editor: Kong JX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Staritz M, Ewe K, Meyer zum Büschenfelde KH. Endoscopic papillary dilation (EPD) for the treatment of common bile duct stones and papillary stenosis. Endoscopy. 1983;15 Suppl 1:197-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Baron TH, Harewood GC. Endoscopic balloon dilation of the biliary sphincter compared to endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy for removal of common bile duct stones during ERCP: a metaanalysis of randomized, controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1455-1460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yasuda I, Tomita E, Enya M, Kato T, Moriwaki H. Can endoscopic papillary balloon dilation really preserve sphincter of Oddi function? Gut. 2001;49:686-691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sato H, Kodama T, Takaaki J, Tatsumi Y, Maeda T, Fujita S, Fukui Y, Ogasawara H, Mitsufuji S. Endoscopic papillary balloon dilatation may preserve sphincter of Oddi function after common bile duct stone management: evaluation from the viewpoint of endoscopic manometry. Gut. 1997;41:541-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fujita N, Maguchi H, Komatsu Y, Yasuda I, Hasebe O, Igarashi Y, Murakami A, Mukai H, Fujii T, Yamao K. Endoscopic sphincterotomy and endoscopic papillary balloon dilatation for bile duct stones: A prospective randomized controlled multicenter trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:151-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Disario JA, Freeman ML, Bjorkman DJ, Macmathuna P, Petersen BT, Jaffe PE, Morales TG, Hixson LJ, Sherman S, Lehman GA. Endoscopic balloon dilation compared with sphincterotomy for extraction of bile duct stones. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1291-1299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ersoz G, Tekesin O, Ozutemiz AO, Gunsar F. Biliary sphincterotomy plus dilation with a large balloon for bile duct stones that are difficult to extract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:156-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 272] [Cited by in RCA: 256] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Attasaranya S, Cheon YK, Vittal H, Howell DA, Wakelin DE, Cunningham JT, Ajmere N, Ste Marie RW, Bhattacharya K, Gupta K. Large-diameter biliary orifice balloon dilation to aid in endoscopic bile duct stone removal: a multicenter series. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:1046-1052. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Maydeo A, Bhandari S. Balloon sphincteroplasty for removing difficult bile duct stones. Endoscopy. 2007;39:958-961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mariani A, Di Leo M, Giardullo N, Giussani A, Marini M, Buffoli F, Cipolletta L, Radaelli F, Ravelli P, Lombardi G. Early precut sphincterotomy for difficult biliary access to reduce post-ERCP pancreatitis: a randomized trial. Endoscopy. 2016;48:530-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, Geenen JE, Russell RC, Meyers WC, Liguory C, Nickl N. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:383-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1890] [Cited by in RCA: 2036] [Article Influence: 59.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, Moore JP, Fennerty MB, Ryan ME, Shaw MJ. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1716] [Cited by in RCA: 1689] [Article Influence: 58.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 13. | Bergman JJ, Rauws EA, Fockens P, van Berkel AM, Bossuyt PM, Tijssen JG, Tytgat GN, Huibregtse K. Randomised trial of endoscopic balloon dilation versus endoscopic sphincterotomy for removal of bileduct stones. Lancet. 1997;349:1124-1129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 292] [Cited by in RCA: 274] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Vlavianos P, Chopra K, Mandalia S, Anderson M, Thompson J, Westaby D. Endoscopic balloon dilatation versus endoscopic sphincterotomy for the removal of bile duct stones: a prospective randomised trial. Gut. 2003;52:1165-1169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Arnold JC, Benz C, Martin WR, Adamek HE, Riemann JF. Endoscopic papillary balloon dilation vs. sphincterotomy for removal of common bile duct stones: a prospective randomized pilot study. Endoscopy. 2001;33:563-567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Freeman ML, DiSario JA, Nelson DB, Fennerty MB, Lee JG, Bjorkman DJ, Overby CS, Aas J, Ryan ME, Bochna GS. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: a prospective, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:425-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 801] [Cited by in RCA: 835] [Article Influence: 34.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Heo JH, Kang DH, Jung HJ, Kwon DS, An JK, Kim BS, Suh KD, Lee SY, Lee JH, Kim GH. Endoscopic sphincterotomy plus large-balloon dilation versus endoscopic sphincterotomy for removal of bile-duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:720-726; quiz 768, 771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Jeong S, Ki SH, Lee DH, Lee JI, Lee JW, Kwon KS, Kim HG, Shin YW, Kim YS. Endoscopic large-balloon sphincteroplasty without preceding sphincterotomy for the removal of large bile duct stones: a preliminary study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:915-922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |