Published online Jul 25, 2016. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v8.i14.496

Peer-review started: March 21, 2016

First decision: May 17, 2016

Revised: May 23, 2016

Accepted: June 14, 2016

Article in press: June 16, 2016

Published online: July 25, 2016

Processing time: 125 Days and 11.2 Hours

We are reporting the rare case of splenic artery aneurysm of 4 cm of diameter presenting as a sub mucosal lesion on gastro-duodenal endoscopy. This aneurysm was treated by endovascular coil embolization and stent graft implantation. The procedure was uneventful. On day 1, the patient presented an acute severe epigastric pain and cardiovascular arrest. Abdominal computed tomography scan showed an active leak of the intravenous contrast dye in the peritoneum from the splenic aneurysm. We performed an emergent resection of the aneurysm, and peritoneal lavage. Postoperatively, hemorrhagic choc was refractory to large volumes replacement, and intravenous vaso-active drugs. On day 2, he presented massive hematochezia. We performed a total colectomy with splenectomy and cholecystectomy for ischemic colitis, with spleen and gallbladder infarction. Despite vaso-active drugs and aggressive treatment with Factor VIIa, the patient died after uncontrolled disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Core tip: Recently, a per-cutaneous endovascular embolization procedure has become the first-line treatment for splenic artery aneurysm. This rare presentation, in this case, as sub-mucosal gastric lesion and bleeding after embolization of the aneurysm showed the gravity of this entity when the diameter of aneurysm is > 2 cm. Although the risk of rupture is low, ruptured splenic artery aneurysm carry a high mortality rate.

- Citation: Tannoury J, Honein K, Abboud B. Splenic artery aneurysm presenting as a submucosal gastric lesion: A case report. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2016; 8(14): 496-500

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v8/i14/496.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v8.i14.496

Splenic artery aneurysms (SAA) are a rare clinical entity that carry the risk of rupture and fatal hemorrhage (particularly those sized > 2 cm). SAA accounts for up to 60% of all splanchnic artery aneurysms and is the third most common intra-abdominal aneurysm following those of the aorta and the iliac arteries[1-7]. The diagnosis is often incidental on abdominal radiologic exams[7-12]. Symptomatic SAA (20%) may present with abdominal pain in the epigastrium or left upper quadrant. A more dramatic mode of presentation is spontaneous rupture of the aneurysm which is reported to occur in 2%-10% of patients as the initial presentation[1-12]. We report here a case of an 82-year-old man with SAA presenting as a sub mucosal lesion on upper gastro-duodenal endoscopy. We will discuss diagnosis tools of SAA, management and potential complications.

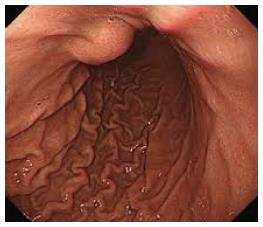

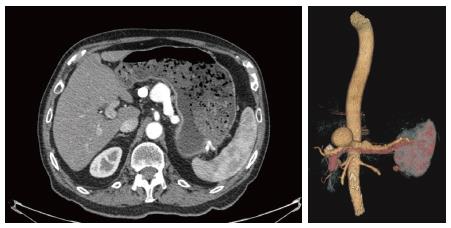

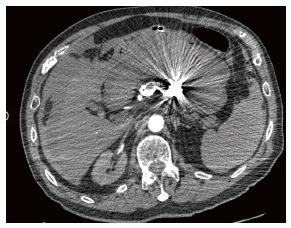

An 82-year-old male patient with a history of hypertension and smoking presented with vague epigastric pain. General physical examination was unremarkable. All labs were within normal limits. He underwent a diagnostic upper gastro-intestinal endoscopy and it showed a 5-cm firm non pulsating submucosal lesion in the fundus suggesting gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) (Figure 1). Endoscopic ultrasound was then performed to characterize the sub mucosal lesion and to perform biopsies. It showed a round anechoic cystic mass measuring 3.5 cm in diameter, communicating with the splenic vessels and showing positive flow on Doppler ultrasound, suggesting a splenic artery aneurysm. Abdominal enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan and angioscan revealed a dilated and tortuous course of the splenic artery with a first saccular aneurysm of 20 mm of diameter behind the stomach lesser curvature, and a second saccular aneurysm of 43 mm of diameter projecting into the stomach (Figure 2). Via a femoral artery catheterization, the patient underwent an endovascular coil embolization and stent graft implantation to treat the aneurysms. The angiographic series taken after the procedure was satisfactory. The procedure was uneventful, and the patient was hemodynamically stable for the first few hours after endovascular repair. On day 1 post embolization, the patient presented an acute severe epigastric pain with rapid drop in arterial pressure and cardiovascular arrest. He was successfully resuscitated and intubated. An urgent abdominal enhancing CT scan revealed active extravasation of the intravenous contrast dye in the peritoneum from the splenic aneurysm confirming the diagnosis of ongoing peritoneal bleeding (Figure 3). We performed an emergent laparotomy with resection of the aneurysm, and peritoneal lavage. The patient is transferred to the intensive care unit. His hemorrhagic choc was refractory to large volumes of isotonic saline, multiple transfusions of packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, platelets, and intravenous vaso-active drugs. On day 2, he presented massive hematochezia. A second laparotomy revealed an extensive ischemic colitis, with spleen and gallbladder infarction, as well as some hypo-perfused regions of the small intestine. We performed a total colectomy with splenectomy and cholecystectomy. Despite vaso-active drugs and aggressive treatment with Factor VIIa, the patient died after uncontrolled disseminated intravascular coagulation.

SAA diagnosis is nearly always a fortuitous discovery by abdominal imaging (CT scan and ultrasound). In our case, the initial presentation was a sub-mucosal non pulsatile lesion detected on an upper gastro-duodenal endoscopy. At our knowledge, this type of presentation has not been described in the literature. Endoscopic ultrasound was initially done with the purpose of performing a fine needle aspiration of the lesion, thought to be a gastric sub-mucosal tumor as GIST. However, the positive Doppler flow detected shifted the diagnosis to a vascular lesion instead of a sub-mucosal tumor, and therefore fine needle aspiration was not performed. The prevalence of SAA is reported to be 0.1%-2%; however, the number of undetected SAAs may be much higher. The clinical presentation is nonspecific in most cases, and the diagnosis of SAA is often an incidental finding[5]. SAAs account for up to 75% of all visceral artery aneurysms and are more commonly reported in female patients than in male patients at a ratio of 4:1. Why SAAs predominate in women is not exactly clear, but a hormonal contribution has been postulated[13]. The pathophysiology of SAA is not fully understood, but local failure of the connective tissue of the arterial wall to maintain the integrity of the blood vessel could be playing a major role. Multiple risk factors have been listed including atherosclerosis, autoimmune diseases, collagen vascular diseases, pancreatitis, portal hypertension, traumatisms, fibromuscular dysplasia, female gender, and history of multiple pregnancies[11-16]. Nearly 70% of the SAA are saccular and situated at splenic hilum bifurcation[6]. Although the risk of rupture is low (nearly 2% of cases), ruptured SAA carry a high mortality rate, approaching 50%. Risk factors for rupture of the aneurysms include pregnancy, development of symptoms, expanding aneurysms, a diameter greater than 2 cm, portal hypertension, porto-caval shunt and liver transplantation[1,3,5,7,12]. Therefore, patients having one or more risk factor should undergo active treatment. Once the diagnosis of SAA is made, the essential goal of the physician remains to choose the adequate patient to treat as well as the right timing of any intervention. It is the general consensus that symptomatic SAA should be treated immediately, since rupture is associated with a high mortality rate. According to the guidelines, treatment is suggested for SAA with diameters > 2 cm or if the SAA is three times greater in diameter than the respective normal artery[5]. To treat symptoms and prevent complications, SAA repair is often required[4]. Various therapeutic options are available for patients with SAA, including conventional open surgery, endovascular treatment and, most recently, laparoscopic surgery[17-26]. Endovascular techniques (EV), including trans-catheter embolization and covered stent placement, can be used to treat most SAA regardless of the clinical presentation, etiology, or location of the aneurysm. If endovascular treatment is technically unavoidable, surgery should be considered given both good results and low morbidity. Open surgical treatment has traditionally been performed. The surgical procedures included ligation of the splenic artery, resection of the aneurysm and vascular reconstruction and/or bypass, and resection of the aneurysm with splenectomy. Complications rate of surgical treatment of non-ruptured aneurysm was 14.3%, and reached 25% in case with rupture[5]. The 30-d mortality rate of surgical treatment was 2.6% in non-ruptured aneurysm and 20.4% in rupture cases[13]. Recently, a per-cutaneous endovascular embolization procedure has become the first-line treatment for SAA. Packing of the aneurysmal sac with embolic agents (most commonly with coils, but also with detachable balloons and inert particles) and exclusion of the aneurysmal neck are the recommended techniques for treating splenic artery aneurysms. In our case, the patient had a 4 cm aneurysm and he was therefore treated with coil embolization and stent graft placement. Although trans-catheter arterial embolization (TAE) is associated with significantly lower morbidity and mortality than are surgical procedures, the possibility of organ ischemia or hemorrhagic events should not be underestimated. The success rate of TAE varies between 75% and 100%, with complication rate (aneurysm re-permeabilization, hemorrhage) ranging from 14% to 25%. The most common complications include acute pancreatitis, splenic infarction, splenic abscess, or intra-peritoneal hemorrhage. In case of an intra-peritoneal hemorrhage with hemodynamic instability, emergent laparotomy with resection of the aneurysm is the treatment of choice, with, however, high morbidity and mortality rate[5]. EV is the most cost-effective treatment for most patient groups with SAAs, independent of the sex and risk profile of the patient. EV is superior over OPEN in costs and effect for all age groups[4]. The results of meta-analysis show that EV of SAA has better short-term results than OPEN. However, OPEN is associated with fewer late complications and re-interventions during follow-up. The results of this meta-analysis show that SAAs > 2 cm should be treated, given the good short-term and long-term results. EV repair has the best outcomes and should be the treatment of choice if the splenic artery has a suitable anatomy for EV repair[13]. In our case, the patient had peritoneal hemorrhage at day 1 post embolization requiring emergent laparotomy. Despite aggressive treatment, the patient died after uncontrolled disseminated intravascular coagulation. In a large cohort evaluating prognostic factors associated with the clinical outcomes after TAE, multivariate analysis confirmed advanced patient age, post procedure thrombocytopenia, post procedure hydrothorax, and the need for a second intervention to be significant prognostic factors for overall 30-d morbidity[13]. In our case, the patient’s advanced age and the need for a second intervention after TAE were two prognostic factors associated with high short term morbidity and mortality.

In conclusion, SAA may be incidentally discovered on an upper gastro-duodenal endoscopy as a sub-mucosal lesion of the stomach. Caution must be made in order not to perform biopsies or fine needle aspiration to such lesions before checking for Doppler flow on endoscopic ultrasound. Treatment of choice for SAA of more than 2 cm of diameter is trans-catheter arterial embolization with a complication rate of around 20%. Intra-peritoneal hemorrhage after EV for SAA carry a high mortality rate despite emergent laparotomy and aggressive medical treatment.

An 82-year-old male patient with a history of hypertension and smoking presented with vague epigastric pain.

General physical examination was unremarkable.

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor, pancreatic mass, gastric tumor.

All labs were within normal limits.

Upper endoscopy showed a 5-cm firm non pulsating submucosal lesion in the fundus, and computed tomography showed two splenic artery aneurysms (SAAs).

Endovascular coil embolization and stent graft implantation, and surgical excision.

SAAs are a rare clinical entity that carry the risk of rupture and fatal hemorrhage (particularly those sized > 2 cm). The diagnosis is often incidental on abdominal radiologic exams. Symptomatic SAA (20%) may present with abdominal pain in the epigastrium or left upper quadrant. A more dramatic mode of presentation is spontaneous rupture of the aneurysm which is reported to occur in 2%-10% of patients as the initial presentation.

SAA may be incidentally discovered on an upper gastro-duodenal endoscopy as a sub-mucosal lesion of the stomach. Caution must be made in order not to perform biopsies or fine needle aspiration to such lesions before checking for Doppler flow on endoscopic ultrasound.

The case is well presented though the language needs to be refined a little. It would be prudent if the authors elaborate a bit on the treatment options including operative mortality (elective vs emergent) and success rates of radiological interventions.

Manuscript Source: Invited manuscript

Specialty Type: Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Country of Origin: Lebanon

Peer-Review Report Classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Arora A, Vennarecci G S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Al-Habbal Y, Christophi C, Muralidharan V. Aneurysms of the splenic artery - a review. Surgeon. 2010;8:223-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Pasha SF, Gloviczki P, Stanson AW, Kamath PS. Splanchnic artery aneurysms. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:472-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Akbulut S, Otan E. Management of Giant Splenic Artery Aneurysm: Comprehensive Literature Review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e1016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hogendoorn W, Lavida A, Hunink MG, Moll FL, Geroulakos G, Muhs BE, Sumpio BE. Cost-effectiveness of endovascular repair, open repair, and conservative management of splenic artery aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61:1432-1440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Pitton MB, Dappa E, Jungmann F, Kloeckner R, Schotten S, Wirth GM, Mittler J, Lang H, Mildenberger P, Kreitner KF. Visceral artery aneurysms: Incidence, management, and outcome analysis in a tertiary care center over one decade. Eur Radiol. 2015;25:2004-2014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Telfah MM. Splenic artery aneurysm: pre-rupture diagnosis is life saving. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014:pii: bcr2014205115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Frasnelli A. Successful resuscitation after splenic artery aneurysm rupture. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2016;9:38-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tétreau R, Beji H, Henry L, Valette PJ, Pilleul F. Arterial splanchnic aneurysms: Presentation, treatment and outcome in 112 patients. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2016;97:81-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Liu B, Zhou L, Liu M, Xie X. Giant peripancreatic artery aneurysm with emphasis on contrast-enhanced ultrasound: report of two cases. J Med Ultrason (2001). 2015;42:103-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lo WL, Mok KL. Ruptured splenic artery aneurysm detected by emergency ultrasound-a case report. Crit Ultrasound J. 2015;7:26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Badour S, Mukherji D, Faraj W, Haydar A. Diagnosis of double splenic artery pseudoaneurysm: CT scan versus angiography. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015:pii: bcr2014207014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wang CX, Guo SL, Han LN, Jie Y, Hu HD, Cheng JR, Yu M, Xiao YY, Yin T, Chu FT. Computed Tomography Angiography in Diagnosis and Treatment of Splenic Artery Aneurysm. Chin Med J (Engl). 2016;129:367-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hogendoorn W, Lavida A, Hunink MG, Moll FL, Geroulakos G, Muhs BE, Sumpio BE. Open repair, endovascular repair, and conservative management of true splenic artery aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2014;60:1667-76.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Parrish J, Maxwell C, Beecroft JR. Splenic Artery Aneurysm in Pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2015;37:816-818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Veluppillai C, Perreve S, de Kerviler B, Ducarme G. Splenic arterial aneurysm and pregnancy: A review. Presse Med. 2015;44:991-994. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Corey EK, Harvey SA, Sauvage LM, Bohrer JC. A case of ruptured splenic artery aneurysm in pregnancy. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2014;2014:793735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Pietrabissa A, Ferrari M, Berchiolli R, Morelli L, Pugliese L, Ferrari V, Mosca F. Laparoscopic treatment of splenic artery aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50:275-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Naganuma M, Matsui H, Koizumi J, Fushimi K, Yasunaga H. Short-term outcomes following elective transcatheter arterial embolization for splenic artery aneurysms: data from a nationwide administrative database. Acta Radiol Open. 2015;4:2047981615574354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Gaba RC, Katz JR, Parvinian A, Reich S, Omene BO, Yap FY, Owens CA, Knuttinen MG, Bui JT. Splenic artery embolization: a single center experience on the safety, efficacy, and clinical outcomes. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2013;19:49-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhang W, Fu YF, Wei PL, E B, Li DC, Xu J. Endovascular Repair of Celiac Artery Aneurysm with the Use of Stent Grafts. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2016;27:514-518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Guang LJ, Wang JF, Wei BJ, Gao K, Huang Q, Zhai RY. Endovascular Treatment of Splenic Artery Aneurysm With a Stent-Graft: A Case Report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e2073. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Reed NR, Oderich GS, Manunga J, Duncan A, Misra S, de Souza LR, Fleming M, de Martino R. Feasibility of endovascular repair of splenic artery aneurysms using stent grafts. J Vasc Surg. 2015;62:1504-1510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yoon T, Kwon T, Kwon H, Han Y, Cho Y. Transcatheter Arterial Embolization of Splenic Artery Aneurysms: A Single-Center Experience. Vasc Specialist Int. 2014;30:120-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Jiang R, Ding X, Jian W, Jiang J, Hu S, Zhang Z. Combined Endovascular Embolization and Open Surgery for Splenic Artery Aneurysm with Arteriovenous Fistula. Ann Vasc Surg. 2016;30:311.e1-311.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sticco A, Aggarwal A, Shapiro M, Pratt A, Rissuci D, D’Ayala M. A comparison of open and endovascular treatment strategies for the management of splenic artery aneurysms. Vascular. 2015; Oct 22; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Dorigo W, Pulli R, Azas L, Fargion A, Angiletta D, Pratesi G, Alessi Innocenti A, Pratesi C. Early and Intermediate Results of Elective Endovascular Treatment of True Visceral Artery Aneurysms. Ann Vasc Surg. 2016;30:211-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |