Published online Jun 25, 2016. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v8.i12.451

Peer-review started: February 9, 2016

First decision: March 14, 2016

Revised: April 6, 2016

Accepted: May 7, 2016

Article in press: May 9, 2016

Published online: June 25, 2016

Processing time: 132 Days and 22.1 Hours

AIM: To evaluate efficacy and safety of clip-and-snare method using pre-looping technique (CSM-PLT) for gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD).

METHODS: In the CSM-PLT method, a clip attached to the lesion side was strangulated with a snare, followed by application of an appropriate tension to the lesion independent of an endoscope. Twenty consecutive lesions were resected by ESD using CSM-PLT (CSM-PLT group) and compared with a control group, including 20 lesions that were resected by conventional ESD. The control group was matched based on the size and location of the lesion, presence of pathologic fibrosis, and experience of endoscopists. Total procedure time of ESD, proportion of en bloc resection, and complications were analyzed.

RESULTS: The total procedure time for the CSM-PLT group was significantly shorter than that for the control group (38.5 min vs 59.5 min, P = 0.023); all lesions were resected en bloc by ESD. There was no significant difference in complications between the two groups. Moreover, there was no complication in the CSM-PLT group. In one large lesion (size: 74 mm) that underwent extensive CSM-PLT during ESD, we used an additional CSM-PLT on another edge of the lesion after achieving submucosal resection to the maximum extent possible during initial CSM-PLT. In two lesions, the snare came off the lesion together with the clip after a sudden pull; nevertheless, ESD was successful in all lesions.

CONCLUSION: CSM-PLT was an effective and safe method for gastric ESD.

Core tip: This was a retrospective matched-pair analysis to evaluate the efficacy and safety of clip-and-snare method using pre-looping technique (CSM-PLT) for gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). CSM-PLT is one of the traction methods that was developed to perform gastric ESD more effectively. Compared with conventional ESD, ESD using CSM-PLT had significantly shorter total procedure time (38.5 min vs 59.5 min, P = 0.023). With regard to proportion of en bloc resection and complications, there was no significant difference between the groups. Hence, CSM-PLT is a promising method for gastric ESD.

- Citation: Yoshida N, Doyama H, Ota R, Takeda Y, Nakanishi H, Tominaga K, Tsuji S, Takemura K. Effectiveness of clip-and-snare method using pre-looping technique for gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2016; 8(12): 451-457

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v8/i12/451.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v8.i12.451

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) was developed in the late 1990s for the purpose of en bloc and less invasive resection of early gastric cancer[1]. In the earliest years, some problems including difficulty of the procedure and high risk of complications were encountered. Over the years, ESD has evolved to become an easier and safer procedure due to establishment of strategies, improvement of devices and injection solution[2], and use of CO2 insufflation pump[3].

Although ESD is performed for early gastric cancer, which satisfies the indication criteria of Japanese guideline[4], difficulty in technicalities of the procedure are still occasionally encountered. The difficulty of gastric ESD depends on the size and location of a tumor, presence of ulceration, or the endoscopist’s skills. Therefore, an innovative technique is necessary to constantly make ESD a safer and more effective procedure, regardless of the characteristic of the lesions or skills of the operator.

Traction method has been described as a technique for an effective ESD; with this technique, an appropriate tension is applied to the lesion to visualize the submucosal layer and effectively perform submucosal dissection. Recently, several traction methods have been reported for use in gastric ESD such as internal traction[5], medical ring[6], clip-with-line (including “dental floss clip traction”)[7-10], use of double-channel endoscope[11], external grasping forceps[12], magnetic anchor[13,14], and the double-scope method[15]. Each method has its advantages and disadvantages[16]; therefore, the most ideal method has not yet been established.

Recently, as new traction method, the clip-and-snare method (CSM), has been reported. CSM is a concept that includes “clip and snare lifting”[17] and “yo-yo technique”[18]. In this technique, the clip attached to the side of the lesion is strangulated with a snare, followed by application of an appropriate tension to the lesion independent of an endoscope. CSM does not only facilitate control of the degree of strength but also of the direction of traction by pulling and pushing the snare. The major difference between “clip and snare lifting”[17] and “yo-yo technique”[18] is the course through which the snare passes. The snare passes through the oral cavity in the “clip and snare lifting”[17], whereas it passes through the nostril in the “yo-yo technique”[18]. Conventional CSM[17,18] entails the use of forceps to derive the snare to the clip; this technique is not easy, particularly for lesions in the upper third of the stomach. We improved this method with a new and easy technique for snare derivation, which we reported as pre-looping technique (PLT)[19] to simplify the CSM technique during gastric ESD on all sites.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of CSM using PLT (CSM-PLT) for gastric ESD.

This retrospective study was conducted at the Ishikawa Prefectural Central Hospital, a tertiary referral center in Japan. In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the said institution. Patients were not required to provide informed consent to the study because the analysis used anonymous clinical data that were obtained after each patient agreed to treatment by written consent. For complete disclosure, the details of the study were published on the home page of Ishikawa Prefectural Central Hospital.

In this manuscript, we reported a retrospective matched-pair comparison of ESD using CSM-PLT with conventional ESD.

From January 2014 to March 2014, 20 consecutive gastric lesions resected by ESD using CSM-PLT were included in the CSM-PLT group. From 1033 gastric lesions resected by conventional ESD between January 2009 and December 2013, we set a control group that included 20 lesions, which matched those of the CSM-PLT group in terms of tumor size, location, pathologic fibrosis, and endoscopist’s experience with ESD. The location and presence of pathologic fibrosis were completely matched. Regarding the location of the lesion, the stomach was divided into the following three longitudinal sections: Upper, middle, and lower; the cross-sectional circumference of the stomach was divided into four equal parts according to the Japanese classification of gastric cancer: Lesser curvature, greater curvature, anterior wall, and posterior wall[20]. Depending on the experience of endoscopists on ESD, further matching was performed. ESD experience was classified into “3 years or under”, “more than 3 years and less than 7 years”, and “7 years or over”. To minimize differences in specimen size, definitive matching was performed. Lesions that extended to the esophagus or duodenum were excluded.

The endoscopists who performed ESD in this study had enough knowledge and skills related to conventional gastric ESD. To ensure the quality of gastric ESD, all of the participated endoscopists were required to have a level of knowledge and skills commensurate with those of a specialist accredited by the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society. In actuality, they had an experience of 4 years or more in gastroscopy. Endoscopists with less than 7 years of experience performed ESD procedures under the supervision of experts with more than 7 years of experience. For the CSM-PLT group, we retrospectively collected consecutive data immediately after the establishment of CSM-PLT. Therefore, all endoscopists who participated in the study had little experience on the established CSM-PLT.

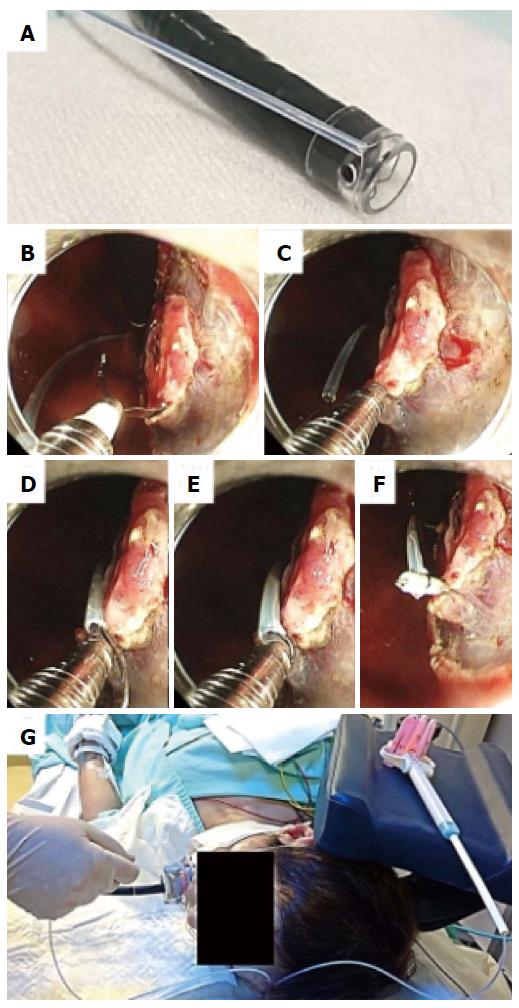

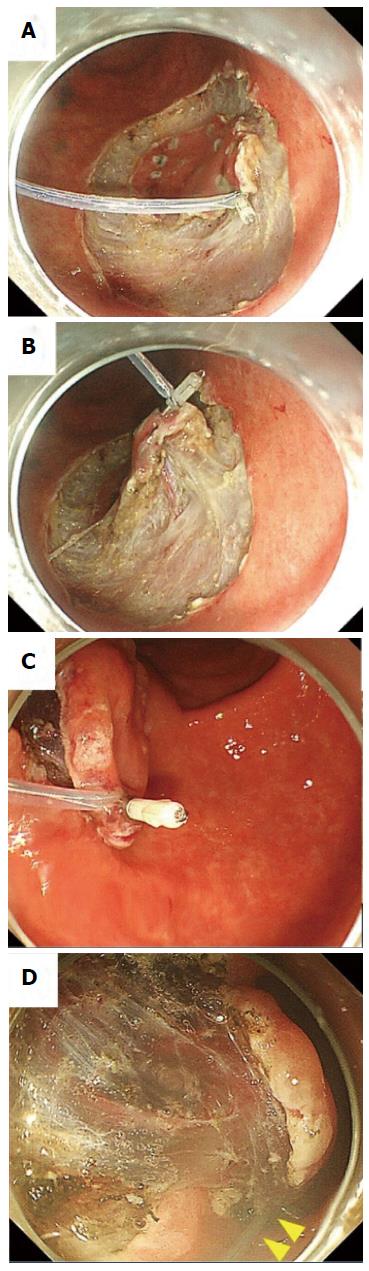

A single-channel endoscope (GIF-Q260J; Olympus Co., Tokyo, Japan) with a disposable transparent cap (D-201-11804, Olympus Co.) on the endoscopic tip was used. A mixture of saline solution, 0.4% sodium hyaluronate, and indigo carmine was injected into the submucosal layer surrounding the lesion, and a circumferential incision was made using an insulation-tipped scalpel (IT knife2, Olympus Co) on ENDO CUT Q mode (effect 2) of the electrosurgical generator (VIO300D, ERBE Co, Tübingen, Germany). The endoscope was withdrawn and the transparent cap was tightened with a snare (SD-221U-25, Olympus Co.) from the outside of the endoscope (Figure 1A); this technique was named PLT[19]. Then, the endoscope and snare were reinserted into the lesion before inserting a hemoclip (HX-610-090, Olympus Co.) with a reusable clip deployment device (EZ CLIP, Olympus Co.) through the endoscope channel. The hemoclip was used to grasp the edge of the tumor while taking utmost care to avoid complete detachment from its deployment device (Figure 1B). The pre-looped snare was loosened from the transparent cap and moved along the device toward the hemoclip (Figure 1C and D). The hemoclip was tightened with the snare and released from the clip deployment device (Figure 1E and F). After this, the endoscopist was able to apply an appropriate tension to the lesion using the snare independent of the endoscope and could incise the submucosal layer effectively (Figure 1G). The submucosal layer was dissected using an IT knife 2 on SWIFT COAG mode (effect 4, 60W) of VIO300D. Because the snare had moderate rigidity, the endoscopist could not only pull but also push the lesion through the snare (Figure 2). Fixing the slider of the snare with clothespins reduced the number of assistants needed for the procedure (Figure 1G). The use of an overtube was not necessarily required. All ESD procedures were performed under unconscious sedation without intubation. We used midazolam, pentazocine, and propofol for appropriate sedation during ESD.

The primary endpoint of this study was comparison of total procedure time of gastric ESD. As secondary endpoints, the proportion of en bloc resection and complications were evaluated.

All videos of ESD procedure have been stored in an electronic archive. From these recorded videos, we measured the total time of the procedure from precutting up to tumor removal. En bloc resection was defined as a one-piece resection of the entire lesion that was endoscopically recognized. Complications included intractable bleeding during ESD, perforation during ESD, delayed perforation, delayed bleeding, and anesthesia-related complications. Intractable bleeding during ESD was defined as operative hemorrhage that required more than 1 min for hemostasis. Delayed perforation was defined as perforation occurring after the day of ESD. Delayed bleeding was defined as bleeding from an ulceration of ESD, which manifested as hematemesis or melena after the day of ESD. Anesthesia-related complications were defined as circulatory disturbance (systolic blood pressure ≤ 90 mmHg or heart rate ≤ 50 beats/min) or respiratory depression (oxygen saturation ≤ 90% in spite of appropriate oxygen support) that were associated with anesthesia and occurred during the procedure.

All descriptive comparisons between the CSM-PLT lesions and their matched controls were made by Wilcoxon signed-rank test for continuous variables and by McNemar test or Bowker test for categorical variables. All P values calculated in this study were two-sided and were not adjusted for multiple testing. P values of < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. All analyses were performed using the statistical software JMP 11 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States). The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Dr. Kunihiro Tsuji from the Department of Clinical Chemotherapy, Ishikawa Prefectural Central Hospital, Ishikawa, Japan.

According to match pairing, the demographics of both groups were completely similar in location, ulceration, specimen size, and experience of operators (Table 1). Additionally, macroscopic type, histologic type, and tumor depth were comparable in both groups.

| CSM-PLT group | Control group | P value | |

| (n = 20) | (n = 20) | ||

| Location | 1.000 | ||

| Upper third | 7 (35) | 7 (35) | |

| Middle third | 7 (35) | 7 (35) | |

| Lower third | 6 (30) | 6 (30) | |

| Macroscopic type | 0.475 | ||

| 0–IIa | 8 (40) | 7 (35) | |

| 0–IIb | 2 (10) | 0 (0) | |

| 0–IIc | 10 (50) | 13 (65) | |

| Specimen size in mm, median (range) | 35.5 (25–74) | 34 (23–75) | 0.999 |

| Ulceration | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 1.000 |

| Histologic type | 0.783 | ||

| Adenoma | 4 (20) | 2 (10) | |

| Tub1 | 14 (70) | 15 (75) | |

| Tub2 | 2 (10) | 2 (10) | |

| Por | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | |

| Tumor depth | 0.655 | ||

| Mucosal | 17 (85) | 18 (90) | |

| Submucosal | 3 (15) | 2 (10) | |

| Experience of ESD, yr | 1.000 | ||

| ≤ 3 | 6 (30) | 6 (30) | |

| 4–6 | 10 (50) | 10 (50) | |

| ≥ 7 | 4 (20) | 4 (20) |

The total procedure time for the CSM-PLT group was significantly shorter than that for the control group (38.5 min vs 59.5 min, P = 0.023). All lesions were resected en bloc by ESD. There was no significant difference between the two groups with regard to the complications. In particular, there was no complication in the CSM-PLT group (Table 2).

| CSM-PLT group | Control group | P value | |

| (n = 20) | (n = 20) | ||

| Total procedure time in minutes, median (range) | 38.5 (8-145) | 59.5 (19-132) | 0.023 |

| En bloc resection, number of lesion (%) | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | - |

| Complications | |||

| Intractable bleeding during ESD, number of times, median (range) | 0 (0-4) | 1 (0-5) | 0.086 |

| Perforation during ESD, number of lesion (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

| Delayed perforation, number of lesion (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

| Delayed bleeding, number of lesion (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (10) | 0.157 |

| Anesthesia-related complications, number of lesions (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

In one large lesion (size: 74 mm) that underwent CSM-PLT during ESD, we used an additional CSM-PLT on another edge of the lesion after achieving the maximum possible submucosal resection during initial CSM-PLT. In two lesions, the snare came off the lesion together with the clip after a sudden pull; CSM-PLT was performed again for one lesion, whereas the other lesion did not undergo additional CSM-PLT because submucosal resection was almost completed with initial CSM-PLT.

The results of this retrospective study have demonstrated that CSM-PLT was able to shorten the total procedure time for gastric ESD without a decline in the proportion of en bloc resection and no increase in complications. A Shortening of the procedure time is clinically significant because it facilitates reduction in dose, duration of exposure, and risks of sedative use during ESD. Furthermore, a shortened procedure time can reduce the working hours of medical staff, including physicians and nurses. Consequently, a reduction in the cost associated with ESD can be expected, as Suzuki et al[10] showed in their article.

We considered two reasons for the shortening of ESD procedure time by CSM-PLT. First, when we lifted the mucosal layer by applying an appropriate tension to a lesion edge, we were able to obtain good visibility of the submucosal layer. Good visualization facilitated the identification of blood vessels and of the dissection line on the submucosal layer. Easy visualization of vascular structures resulted in easier hemostasis and pre-coagulation of vessels at a risk of bleeding. Identification of the dissection line greatly contributed to incision speed and safety. In this regard, it is necessary to understand that compared with conventional ESD, in ESD using CSM-PLT, the muscular layer may be elevated by traction. Accordingly, to avoid perforation during ESD using CSM-PLT, resection after recognizing a proper dissection line is more important. Second, the taut submucosal layer with traction allowed endoscopists to incise it with less power such as that for cutting a taut paper with a knife. These advantages are thought to be common among the other traction methods.

CSM-PLT is more advantageous than other traction methods. First, it not only facilitates the control of the degree of strength but also of the direction of traction. With the use of CSM-PLT, we could coordinate a two-way direction by pulling and pushing the snare, although the double-scope method would be more controllable[15]. In contrast, internal traction[5] and medical ring[6] cannot coordinate both traction strength and direction. Clip-with-line[7-10] can only pull but not push a lesion. Because traction adjustment is the most important factor in the traction method, this point was a major advantage of CSM-PLT. Second, PLT[19], which is a new method for the delivery of a snare, made it easy to perform CSM for lesions on all sites of the stomach. Because the delivery of a device for traction is difficult for lesions located on the upper third of the stomach, performing conventional CSM or other traction methods, such as external forceps method[12], is usually a challenge for such lesions. In one report involving one conventional CSM for intragastric proximal lesions, the procedure was successful in only one lesion on the corpus[18]. PLT facilitated grasping of the clip by the snare, particularly in cases wherein the clip was attached to the anal side of the tumor on the upper third of the stomach (Figure 1). In this report, we performed CSM-PLT and accomplished ESD for seven upper third lesions. Furthermore, PLT enabled the use of CSM even in ESD without an overtube; this would be an advantage for institutions where an overtube is not usually used. Third, because snare and hemoclip are common devices in almost all institutions where ESD is performed, CSM-PLT may be easily reproducible.

However, there are some disadvantages of CSM-PLT. Interference between the endoscope and snare may occur to some extent, despite the use of a thin snare with a maximum external diameter of 1.8 mm. A snare may detach from the lesion together with the clip when the endoscope is manipulated roughly. In fact, this situation occurred in two cases in this study. To avoid this, it is necessary for endoscopists to move the endoscope with care. It would also help if an assistant secures the snare tube on the mouthpiece of the patient during considerable manipulation of the endoscope by the operator. In addition, the incurred costs of the clip and snare are also a limitation of the method.

As Imaeda et al[16] described in their review, each of the several traction methods reported has both advantages and disadvantages. It is generally considered that traction method is useful for ESD, but it is unknown which technique is the best at present. As the advantages and disadvantages differ among the techniques, sufficient understanding of each method is needed for choosing the optimal procedure for an endoscopist and an institution. We are certain that CSM-PLT can become one of the promising alternative traction methods for gastric ESD.

There were several limitations of our study. First, it was conducted as a retrospective, single-institution study. Second, the sample size was small and subgroup analysis was not feasible. There were few lesions, such as large lesions or lesions with ulceration, which were typically difficult to treat by conventional ESD. In this study, we could not examine the efficacy and safety of CSM-PLT on these refractory lesions. At present, we are increasing the number of cases and we plan to clarify the characteristics of lesions for which CSM-PLT would be more effective. Third, because the control group in this study included lesions that were resected conventional ESD, we cannot be certain whether CSM was more useful than the other traction methods. Further prospective, multi-institutional studies are warranted to confirm the efficacy and safety of CSM-PLT.

In conclusion, the CSM-PLT was an effective and safe technique for gastric ESD. CSM-PLT is a promising method, and we believe that it can contribute to further development of ESD.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is one of the standard treatments for early gastric cancer. However, ESD is complicated and difficult. Therefore, a technique that will facilitate ESD is desired.

Several traction methods, which apply appropriate tension to the lesion in order to visualize the submucosal layer, have been described as techniques for an effective ESD.

Clip-and-snare method using pre-looping technique (CSM-PLT) is a type of traction method. CSM-PLT enables control of the degree and two-way direction of traction with the use of commonly available devices, such as hemoclip and snare.

CSM-PLT is considered to be effective when endoscopists who are able to perform conventional ESD apply it for lesions which conventional ESD have been intended for.

CSM (clip-and-snare method): A genetic term for a traction method that facilitates control of traction to the lesion with the use of a snare, which strangulates a clip attached to the lesion. CSM-PLT: CSM using pre-looping technique, which is a new technique for snare delivery, facilitates easy performance of CSM for lesions on all sites of the stomach.

This is a very interesting and very well done case-control study which tries to evaluate a new additional method for shortening the time spent during ESD and for making it easier and safer.

P- Reviewer: Amornyotin S, Rabago L S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Jiao XK

| 1. | Ono H, Kondo H, Gotoda T, Shirao K, Yamaguchi H, Saito D, Hosokawa K, Shimoda T, Yoshida S. Endoscopic mucosal resection for treatment of early gastric cancer. Gut. 2001;48:225-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1134] [Cited by in RCA: 1149] [Article Influence: 47.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 2. | Yamamoto H, Yahagi N, Oyama T, Gotoda T, Doi T, Hirasaki S, Shimoda T, Sugano K, Tajiri H, Takekoshi T. Usefulness and safety of 0.4% sodium hyaluronate solution as a submucosal fluid “cushion” in endoscopic resection for gastric neoplasms: a prospective multicenter trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:830-839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Maeda Y, Hirasawa D, Fujita N, Obana T, Sugawara T, Ohira T, Harada Y, Yamagata T, Suzuki K, Koike Y. A prospective, randomized, double-blind, controlled trial on the efficacy of carbon dioxide insufflation in gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection. Endoscopy. 2013;45:335-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ono H, Yao K, Fujishiro M, Oda I, Nimura S, Yahagi N, Iishi H, Oka M, Ajioka Y, Ichinose M. Guidelines for endoscopic submucosal dissection and endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer. Dig Endosc. 2016;28:3-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 354] [Cited by in RCA: 407] [Article Influence: 45.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chen PJ, Chu HC, Chang WK, Hsieh TY, Chao YC. Endoscopic submucosal dissection with internal traction for early gastric cancer (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:128-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Matsumoto K, Nagahara A, Sakamoto N, Suyama M, Konuma H, Morimoto T, Sagawa E, Ueyama H, Takahashi T, Beppu K. A new traction device for facilitating endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for early gastric cancer: the “medical ring”. Endoscopy. 2011;43 Suppl 2 UCTN:E67-E68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Oyama T, Shimaya S, Tomori A, Hotta K, Miyata Y, Yamada S. Endoscopic mucosal resection using a hooking knife (hooking EMR). Stomach Intest. 2002;37:1155-1161. |

| 8. | Jeon WJ, You IY, Chae HB, Park SM, Youn SJ. A new technique for gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection: peroral traction-assisted endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:29-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yoshida M, Takizawa K, Ono H, Igarashi K, Sugimoto S, Kawata N, Tanaka M, Kakushima N, Ito S, Imai K. Efficacy of endoscopic submucosal dissection with dental floss clip traction for gastric epithelial neoplasia: a pilot study (with video). Surg Endosc. 2015;Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Suzuki S, Gotoda T, Kobayashi Y, Kono S, Iwatsuka K, Yagi-Kuwata N, Kusano C, Fukuzawa M, Moriyasu F. Usefulness of a traction method using dental floss and a hemoclip for gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection: a propensity score matching analysis (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:337-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yonezawa J, Kaise M, Sumiyama K, Goda K, Arakawa H, Tajiri H. A novel double-channel therapeutic endoscope (“R-scope”) facilitates endoscopic submucosal dissection of superficial gastric neoplasms. Endoscopy. 2006;38:1011-1015. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Imaeda H, Iwao Y, Ogata H, Ichikawa H, Mori M, Hosoe N, Masaoka T, Nakashita M, Suzuki H, Inoue N. A new technique for endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer using an external grasping forceps. Endoscopy. 2006;38:1007-1010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kobayashi T, Gotohda T, Tamakawa K, Ueda H, Kakizoe T. Magnetic anchor for more effective endoscopic mucosal resection. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2004;34:118-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gotoda T, Oda I, Tamakawa K, Ueda H, Kobayashi T, Kakizoe T. Prospective clinical trial of magnetic-anchor-guided endoscopic submucosal dissection for large early gastric cancer (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:10-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ahn JY, Choi KD, Choi JY, Kim MY, Lee JH, Choi KS, Kim DH, Song HJ, Lee GH, Jung HY. Transnasal endoscope-assisted endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric adenoma and early gastric cancer in the pyloric area: a case series. Endoscopy. 2011;43:233-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Imaeda H, Hosoe N, Kashiwagi K, Ohmori T, Yahagi N, Kanai T, Ogata H. Advanced endoscopic submucosal dissection with traction. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;6:286-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yasuda M, Naito Y, Kokura S, Yoshida N, Yoshikawa T. Sa1687 Newly-Developed ESD (CSL-ESD) for Early Gastric Cancer Using Convenient and Low-Cost Lifting Method (Lifting Method Using Clips and Snares) for Lesions is Clinically Useful. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:AB244. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Baldaque-Silva F, Vilas-Boas F, Velosa M, Macedo G. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastric lesions using the “yo-yo technique”. Endoscopy. 2013;45:218-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yoshida N, Doyama H, Ota R, Tsuji K. The clip-and-snare method with a pre-looping technique during gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection. Endoscopy. 2014;46 Suppl 1 UCTN:E611-E612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:101-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2390] [Cited by in RCA: 2873] [Article Influence: 205.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |